Abstract

This Excessive sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption and low health literacy skills have emerged as two public health concerns in the United States (US); however, there is limited research on how to effectively address these issues among adults. As guided by health literacy concepts and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), this randomized controlled pilot trial applied the RE-AIM framework and a mixed methods approach to examine a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intervention (SipSmartER), as compared to a matched-contact control intervention targeting physical activity (MoveMore). Both 5-week interventions included two interactive group sessions and three support telephone calls. Executing a patient-centered developmental process, the primary aim of this paper was to evaluate patient feedback on intervention content and structure. The secondary aim was to understand the potential reach (i.e., proportion enrolled, representativeness) and effectiveness (i.e. health behaviors, theorized mediating variables, quality of life) of SipSmartER. Twenty-five participants were randomized to SipSmartER (n=14) or MoveMore (n=11). Participants’ intervention feedback was positive, ranging from 4.2–5.0 on a 5-point scale. Qualitative assessments reavealed several opportunties to improve clarity of learning materials, enhance instructions and communication, and refine research protocols. Although SSB consumption decreased more among the SipSmartER participants (−256.9 ± 622.6 kcals), there were no significant group differences when compared to control participants (−199.7 ± 404.6 kcals). Across both groups, there were significant improvements for SSB attitudes, SSB behavioral intentions, and two media literacy constructs. The value of using a patient-centered approach in the developmental phases of this intervention was apparent, and pilot findings suggest decreased SSB may be achieved through targeted health literacy and TPB strategies. Future efforts are needed to examine the potential public health impact of a large-scale trial to address health literacy and reduce SSB.

Keywords: beverages, health literacy, health education, public health, health behavior, pilot projects

1. INTRODUCTION

High sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption and low health literacy skills have emerged as two broad public health concerns in the United States (US). For example, SSB consumption has approximately doubled in the past two decades and contributes about 10% of the total calories (kcal) in the US diet [1]. While excessive SSB intake has been associated with numerous adverse health outcomes [2], there is limited research on how to effectively improve SSB behaviors among adults. Furthermore, it is estimated that one-third of Americans have low health literacy skills [3]. Low health literacy has been associated with poorer health outcomes [4], and one study found health literacy was a stronger predictor of SSB consumption relative to educational achievement or income [5]. However, taken as a whole, intervention approaches to mitigate the effects of low health literacy have been mixed [4]. Two plausible explanations include the deficiency of health behavior theory to guide health literacy intervention approaches and the lack of pilot studies to refine intervention messages, strategies to improve health literacy, and recruitment and retention approaches for low literate audiences [4, 6]. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of addressing SSB intake through intervention approaches guided by health behavior theory and health literacy, as well as the need for pilot studies to help advance intervention development and implementation.

To date, there is limited research on how to address SSB behaviors among adults [7–9], and none of which report an underlying theoretical approach or the potential influence of health literacy status on behavior change. Likewise, no study, to date, has reported on engaging prospective participants to elicit feedback on the development of SSB intervention content and structure to ensure that it is relevant to the target population [10]. Therefore, an important starting point for assessing the acceptability and potential effectiveness of an SSB behavioral intervention is to gather information directly from the target population [11]. In addition to the refinement of research methods, instrumentation, and hypothesis, taking advantage of opportunities to execute a patient-centered developmental process can help more fully understand patients’ receipt and value of the theory-driven intervention content and communication approaches [11, 12].

The overall goals of this 5-week, 2-arm randomized controlled trial was to apply a patient-centered developmental process to inform the refinement of intervention content and communication approaches, as well as pilot test the effects of an intervention to decrease SSB consumption (SipSmartER) when compared to a matched-contact control condition targeting increasing physical activity behaviors (MoveMore). Both treatment conditions were guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [13] and concepts in health literacy [14], including media literacy [15]. Further, the structure and evaluation of the intervention was informed by the RE-AIM framework to heighten its likelihood for translation into practice by considering factors related to reach and effectiveness at the individual level and the potential adoption, implementation, and maintenance at the organizational level [16]. Hence, the primary aim of this paper is to evaluate patient feedback on intervention content and structure. The secondary aim was to understand the potential reach (i.e., proportion enrolled, representativeness) and effectiveness (i.e. health behaviors, theorized mediating variables, quality of life) of SipSmartER. Although the small sample of this pilot study limits statistical power, it was hypothesized that when compared to the matched-contact control participants, SipSmartER participants would trend towards greater decreases in SSB intake and improvements in mediating TPB-SSB variables.

2. METHODS

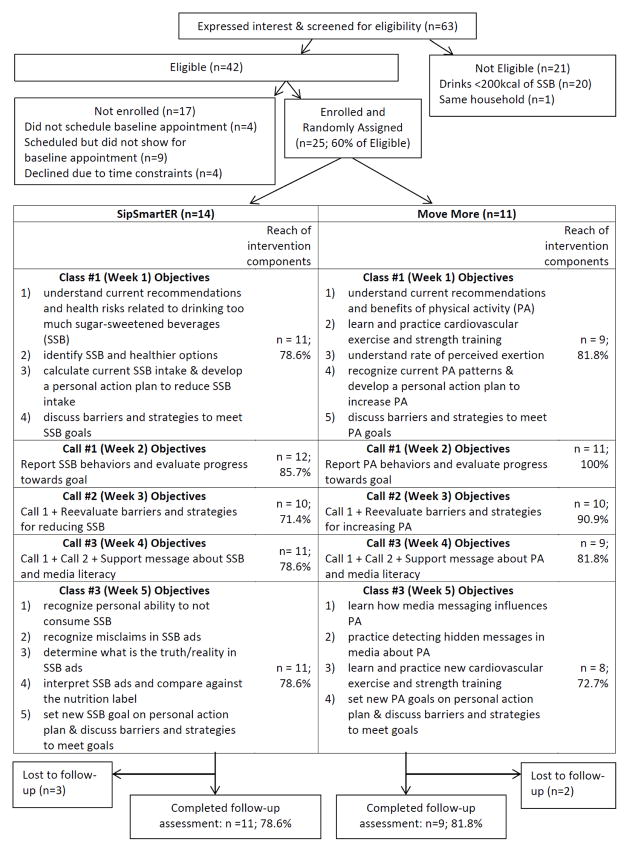

After approval by Virginia Tech’s Institutional Review Board, written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment in October 2011. Both conditions consisted of two 90-minute small group sessions and three 5–10 minute telephone calls (Figure 1). Previously executed focus groups guided content development for key messages [17], and program components were specifically designed to address TPB constructs including attitudes, subjective norms, percieved behavioral control, and behavioral intentions for the referent behaviors (i.e. either SSB or PA). Integration of health literacy concepts included minimization of print materials, use of engaging visual-based activities, use of simplifed print materials written at <8th grade level, strong integration of media literacy concepts, and use of intervention staff trained in clear communication techniques. Throughout the program, participants developed and updated personalized action plans and used diaries to track behaviors.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram and program objective overview of SipSmartER and MoveMore conditions

Participants were recruited via flyers and word of mouth from one community and one healthcare center in Roanoke, Virginia. Eligibility criteria included ≥18 years of age, English-speaking, without medical conditions that contraindicate physical activity, and consuming >200 SSB kcals/day as assessed with the validated 15-item Beverage Questionnaire (BEVQ-15) [18]. Forty-two of sixty-three screened individuals were eligible. Twenty-five completed enrollment and were randomized to SipSmartER (n=14) or Move More (n=11) (Figure 1).

At the end of each group session, participants completed a self-administered process evaluation regarding session content and delivery which included seven 5-point likert scale questions and three open-eneded questions.

After the program, participants completed an interviewer-administered qualitative assessment that included 24 semi-structured questions related to group sessions, personal action plans, diaries, and telephone calls.

Outcome data collection occurred at baseline and upon completion of the program (week 6), and each took approximately 45–60 minutes. Previously validated instruments were utilized, including: 1) 15-item BEVQ-15 [18], 2) 20-item Theory of Planned Behavior questionnaire for SSB [19], 3) 9-item media literacy adapted to reflect SSB [20], and 4) 2 quality of life questions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [21]. Additional baseline measures included 9 demographic questions, the 6-item validated Newest Vital Sign to assess health literacy [22], and height and weight using standardized protocol. Participants were provided $25 and $50 gift cards, respectively, for completing baseline and follow-up assessments.

Qualitative data were coded as specific to group sessions, personal action plans, diaries, telephone calls, or non-specific, then coded as positive or negative, and subsequently examined for emerging themes. Quantitative statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical analysis software, version 20. Descriptive statistics and chi-squared tests were used to summarize all quantitative measures. ANOVA tests were used to analyze group effects and group by time effects.

3. RESULTS

Of the 25 enrolled participants, 19 (76%) were female and 6 (24%) were male. Participants’ mean age was 42 (SD=14) years, and were primarily Caucasian (n=13; 52%) or African American (n=12; 48%). Nine (36%) had a high school education or less and 21 (84%) reported <$25,000 annual household income. Health literacy status indicated 6 (24%) participants with a high likelihood of limited literacy skills, 7 (28%) with a possibility of limited literacy skills, and 11 (44%) with adequate literacy skills. Eight participants (32%) were overweight and 16 (64%) were obese. There were no significant differences between groups for any demographic variables except education level (SipSmartER > MoveMore; F=5.57; p=0.03). When compared to US census data, our sample appeared representative with the exception that men were underrepresented, while African Americans and those with lower income or education levels were overrepresented. The conditions did not differ on the reach of different intervention components (i.e., attendance, F=0.01; p=0.94; call completion, F=0.91; p=0.35; Figure 1).

Related to participants’ assessment of content and structure of the group classes, mean scores were relatively high for both conditions and both classes, ranging from 4.2–5.0 on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Table 1). Lesson components that were favored among SipSmartER group sessions emerged: realizing how much sugar is in beverages, recognizing the health risks associated with drinking too much sugar, understanding how much sugar they were consuming, learning about better alternatives, and learning about the media’s role in influencing SSB companies and how advertisements leave out important information on health. Participants concluded that hands on activities (e.g. learning about serving sizes, counting sugar packets) were fun and engaging. Overall, participants thought group sessions were “very beneficial,” “very informative,” “fun,” “captivating,” and “time well spent.” Suggested improvements included bringing speakers for the laptops, increasing the session duration, and encouraging more participant discussion and questions.

Table 1.

Process & Outcome Results of SipSmartER and MoveMore conditions

| SipSmartER Mean (SD) (n = 11) | MoveMore Mean (SD) (n=9) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Class #1 | Class #2 | Class #1 | Class #2 | |

| Process Evaluationa | ||||

| The session was well organized. | 4.9 (0.3) | 5.0 (0) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (1.3) |

| The information was easy to understand. | 4.9 (0.3) | 5.0 (0) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.5 (1.3) |

| The activities were fun. | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.4 (1.4) |

| The session was the right amount of time. | 4.8 (0.4) | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.2 (1.3) |

| I learned things in the session that I did not know before. | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.4 (1.4) |

| The presenters seemed to understand my concerns. | 4.9 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.5 (1.3) |

| The presenters knew what they were talking about. | 5.0 (0) | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.5) | 4.5 (1.3) |

| SipSmartER Mean (SD) (n = 11) | Move More Mean (SD) (n = 9) | Overall Effects | Between Groups Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| Outcome Evaluation | ||||||

| Health behaviors | ||||||

| Sugar-sweetened beverage kcals/day | 537.5 (633.3) | 280.6 (261.4) | 574.8 (389.3) | 375.1 (251.6) | F = 3.58 P = 0.08 |

F = 0.06 P = 0.82 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage ounces/day | 44.1 (49.4) | 24.1 (21.7) | 49.6 (30.0) | 33.2 (22.7) | F = 3.72 P = 0.07 |

F = 0.04 P = 0.85 |

| Theory of Planned Scales for Sugar-sweetened Beverages b | ||||||

| Affective attitudes (3 items) | 3.4 (1.5) | 4.4 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.3) | 4.6 (1.0) | F = 9.57 P = 0.01 |

F = 0.10 P = 0.76 |

| Instrumental attitudes (3 items) | 4.6 (1.5) | 5.8 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.0) | 6.1 (0.8) | F = 10.51 P < 0.01 |

F = 1.95 P = 0.18 |

| Subjective norms (3 items) | 5.0 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.2) | F = 1.40 P = 0.25 |

F = 0.06 P = 0.80 |

| Perceived behavioral Control (3 items) | 5.4 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.7) | 5.4 (2.0) | F = 0.51 P = 0.49 |

F = 0.09 P = 0.77 |

| Behavioral intention Total (4 items) | 4.9 (1.6) | 5.5 (1.5) | 4.9 (0.8) | 5.6 (1.1) | F = 7.04 P = 0.02 |

F = 0.10 P = 0.76 |

| Media literacy scales for sugar-sweetened beverages c | ||||||

| Authors/audiences (5 items) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) | F = 2.25 P = 0.15 |

F = 0.77 P = 0.39 |

| Meanings/messages (9 items) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.3) | F = 16.06 P < 0.01 |

F = 0.05 P = 0.83 |

| Representation/reality (5 items) | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.5) | F = 4.31 P = 0.05 |

F = 0.57 P = 0.46 |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| Rate your general health d | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.0) | F = 0.31 P = 0.59 |

F = 0.31 P = 0.59 |

| In past 30 day, how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from usual activities | 5.3 (8.9) | 5.6 (9.0) | 5.2 (10.5) | 6.1 (10.2) | F = 0.87 P = 0.36 |

F = 0.12 P = 0.74 |

Reported on a 5-point Likert Scale: 1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree

Reported on a 5-point Likert Scale: 1= worse, 5= better attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intentions

Reported on a 4-point Likert Scale: 1=definetly no, 4=definetly yes

Reported on a 5-point Likert Scale: 1=excellent, 5=poor

Themes that emerged for the personal action plans were that it encouraged responsibility and accountability, offered ideas about strategies to overcome barriers, helped make goals achievable, and helped to visualize goals. The primary dislike was about the time needed to complete it. While some participants enjoyed the challenge of setting and achieving goals, other participants stated this challenge as a dislike.

The major positive emergent theme related to drink diaries included the accountability with tracking daily amounts of SSB. However, most participants disliked the amount of time to record behaviors and struggled with remembering to complete the diary. Most participants expressed ease when asked about figuring out SSB weekly averages, “All you have to do is add them up and divide by the days.” However, a few participants expressed difficulties, “It was hard to look through each day and each time per day.”

When asked about the telephone calls, SipSmartER participants concluded that they were “supportive,” “kept me motivated,” and “made it fun.” Dislikes included the timing of the calls with one participant stating, “It was hard to get calls at work or when I was driving.” Most participants liked reporting their SSB intake over the phone with one stating, “It was nice to speak with someone and set another goal.” When asked about strategies offered over the phone, one participant stated, “They were helpful, gave me new ideas, and nothing that I had thought about before.”

Only one participant stated that the calls were not helpful, because they did not have any barriers, while another participant suggested that the phone calls needed to be less scripted. Quantitatively, there was a significant time effect on a number of study outcomes (Table 1). Specifically, across groups, there were significant improvements in SSB behaviors, SSB affective and instrumental attitudes, SSB behavioral intention, and two media literacy outcomes (meanings/messages, e.g., SSB companies create messages for certain purposes; representation/reality, e.g., SSB commercials omit certain health information). However, SSB reduction differences between SipSmartER compared to MoveMore participants were not significant (SipSmartER −256.9 ± 622.6 kcals versus MoveMore −199.7 ± 404.6 kcals). There were no significant differences for quality of life measures, suggesting no unintended or potential negative consequences.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first known study to engage participants in the refinement of an intervention integrating concepts from health literacy with the TPB to reduce SSB behaviors among adults. As identified in the seminal health literacy review by Berkman and colleagues [4], pilot tested interventions, which engage the target population, result in greater effects. Similarly to conclusions by Berkman and colleagues [4], the observations of, and information gathered from representatives of the target population provided a number of key points to consider for the larger trial, including: 1) refinement of small group sessions (e.g. earlier integration of action planning, promote more participant dialogue, change duration to 120 minutes), 2) incorporate explicit teach back methods in the calls (e.g. assess understanding of SSB types, servings sizes, calculating averages) to add clarity to the instructions and learning materials, as well as reduce recall bias and variability while addressing the sensitivity of the primary outcome measure, and 3) refinement of recruitment and enrollment protocols. The value of using a patient-centered approach in the developmental phases of this theory-guided SSB behavioral intervention was apparent.

In general, the behavior change, while not significantly different between groups, trended in the direction hypothesized (i.e. greater SSB improvements in the SipSmartER as compared to the MoveMore). Being made aware of the study purpose through informed consent procedures and the repeated exposure to SSB recommendations through the assessment process may have prompted SSB improvements in the control group. This is consistent with the literature on mere-measurement effects, which demonstrates short-term (but not long-term) behavioral responses to sets of questions related to measurement of behavioral and psychosocial constructs similar to those proposed in our study [23]. It is hypothesized that an adequately powered trial, of longer duration and timing between data assessment points, will overcome this challenge.

The RE-AIM approach for planning the intervention seemed to be successful in creating a structure that could consistently reach the study sample and including content that they enjoyed [16]. This initial feedback from participants provides promising directions for understanding the reach (including representativeness) and effectiveness of a TPB and health literacy-based SSB intervention. Future evaluative efforts will include assessing reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance to promote comprehensive understanding of internal and external validity factors, as well as potential public health impact of a large-scale trial to reduce SSB.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the research support provided by Terri Corsi, Sarah Wall, Valisa Hedrick, Lauren Noel, Angie Bailey, Ramine Alexander, and Felicia Reese. We are particularly grateful for contributions from Eileen Lepro at New Horizons Healthcare and staff at the Presbyterian Community Center. This research was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute 1R01CA154364-01A1 (Zoellner, PI)

References

- 1.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Shifts in patterns and consumption of beverages between 1965 and 2002. Obesity. 2007;15:2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:667–675. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkman NSS, Donahue K, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An update of the literacy and health outcomes systematic review of the literature. Chapel Hill, NC: RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoellner J, You W, Connell C, et al. Health literacy is associated with Healthy Eating Index scores and sugar-sweetened beverage intake: Findings from the rural lower Mississippi Delta. Journal of American Dietetic Association. 2011;111:1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen K, Zoellner J, Motley M, et al. Understanding the internal and external validity of health literacy interventions: a systematic literature review using the RE-AIM framework. The Journal of Health Communication. 2010;16(Suppl 3):55–72. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate DF, Turner-McGrievy G, Lyons E, et al. Replacing caloric beverages with water or diet beverages for weight loss in adults: main results of the Choose Healthy Options Consciously Everyday (CHOICE) randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95:555–563. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stookey JD, Constant F, Popkin BM, et al. Drinking water is associated with weight loss in overweight dieting women independent of diet and activity. Obesity. 2008;16:2481–2488. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LW, Appel LJ, Loria C, et al. Reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with weight loss: the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1299–1306. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen K-Y, Miller SM, Stanton AL, et al. The development and preliminary testing of a multimedia patient provider survivorship communication module for breast cancer survivors. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;88:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helfand M, Berg A, Flum D, et al. Draft Methodology Report: “Our Questions, Our Decisions: Standards for Patient-centered Outcomes Research”. http://pcori.org/assets/MethodologyReport-Comment.pdf.

- 12.Venetis MK, Robinson JD, Turkiewicz KL, et al. An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: A meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer D. Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aufderheide P. Communications and Society Program of the Aspen Institute. Washington DC: 1993. Part II: Conference Proceedings and Next Steps. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoellner J, Krzeski E, Harden S, et al. Qualitative Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Beverage Consumption Behaviors among Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112:1774–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedrick VE, Savla J, Comber DL, et al. Development of a Brief Questionnaire to Assess Habitual Beverage Intake (BEVQ-15): Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Total Beverage Energy Intake. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112:840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoellner J, Estabrooks P, Davy B, et al. Exploring the Theory of Planned Behavior to explain Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2012;44:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Primack BA, Gold MA, Switzer GE, et al. Development and validation of a smoking media literacy scale for adolescents. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:369–374. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klesges R, Eck L, Mellon M, et al. The accuracy of self-reports of physical activity. Medical Science Sports and Exercise. 1990;22:690–697. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199010000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss B, Mays M, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The Newest Vital Sign. Annuals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levav J, Fitzsimons G. When questions change behavior: The role of ease representation. Physcological Science. 2006;17:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]