Abstract

Background

Millions of patients who survive medical and surgical general ICU care every year suffer from newly acquired long-term cognitive impairment and profound physical and functional disabilities. To overcome the current reality in which patients receive inadequate rehabilitation, we devised a multi-faceted, in-home tele-rehabilitation program implemented using social workers and psychology technicians with the goal of improving cognitive and functional outcomes.

Methods

This was a single-site, feasibility, pilot randomized trial of 21 general medical/surgical ICU survivors (8 controls and 13 intervention patients) with either cognitive or functional impairment at hospital discharge. After discharge, study controls received usual care (sporadic rehabilitation) while intervention patients received a combination of in-home cognitive, physical, and functional rehabilitation over a 3-month period via a social worker or master's level psychology technician utilizing telemedicine to allow specialized multi-disciplinary treatment. Interventions over 12 weeks included 6 in-person visits for cognitive rehabilitation and 6 televisits for physical/functional rehabilitation. Outcomes were measured at the completion of the rehabilitation program (i.e., at 3 months) with cognitive functioning as the primary outcome. Analyses were conducted using linear regression to examine differences in 3-month outcomes between treatment groups while adjusting for baseline scores.

Results

Patients tolerated the program with only 1 adverse event (AE) reported. At baseline both groups were well-matched. At 3-month follow-up, intervention group patients demonstrated significantly improved cognitive executive functioning on the widely used and well-normed Tower Test (TOWER) (for planning and strategic thinking) versus controls [13.0 (Interquartile Range, IQR 11.5 to14.0) vs. 7.5 (4.0 to 8.5), adjusted p<0.01]. Intervention group patients also reported better performance (i.e., lower score) on one of the most frequently employed measures of functional status [Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ)] at 3 months vs. controls [1.0 (0.0 to 3.0) vs. 8.0 (6.0 to 11.8), adjusted p=0.04].

Conclusions

A multi-component rehabilitation program for ICU survivors combining cognitive, physical, and functional training appears feasible and possibly effective in improving cognitive performance and functional outcomes in just 3 months. Future investigations with a larger sample size should be conducted to build on this pilot, feasibility program and to confirm these results as well as to elucidate the elements of rehabilitation contributing most to improved outcomes.

Keywords: brain injury, cognitive impairment, functional disability, physical therapy, occupational therapy, rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

Millions of individuals survive bouts of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), severe sepsis and other forms of critical illness annually, only to develop significant and long-lasting cognitive impairment and physical and functional debility (1-4)(5). Cognitive impairment affects as many as 2 out of 3 intensive care unit (ICU) survivors and is often persistent, especially following ARDS and sepsis (3, 6-9). ICU-related cognitive impairment is particularly pronounced with regard to executive functioning (EF), the set of abilities involved in complex thinking included in planning, initiating, shifting/sequencing, monitoring and inhibiting which enable individuals to engage in purposeful, goal directed behaviors (10-13). Physical debility is similarly common after critical illness (14-16), with self-reported muscle weakness and general physical limitations occurring widely among patients with ARDS and sepsis (17). The physical debility, thought to be due to deconditioning compounded by critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy (18), can affect up to 90% of patients requiring prolonged intensive care and can greatly impede recovery (19). With regard to functional ability, one recent study reported that 7 years after discharge, only 52% of survivors were able to return to normal (8).

Unfortunately, the cognitive and physical impairments encountered following critical illness are often not formally recognized and infrequently treated. With the exception of patients with overt cardiac disease (e.g., heart surgery) or frank brain injury (e.g., traumatic brain injury or stroke), only a small percentage of ICU survivors receive formal rehabilitation once they leave the hospital (20). This state of affairs is concerning in view of the large potential for gain via rehabilitation considering the often “acquired” as opposed to “degenerative” nature of their brain, muscle, and nerve injuries. In the few circumstances in which ICU survivors do receive rehabilitation, it typically occurs in normal rehabilitation contexts and is not designed to meet the specific combination of cognitive, psychological, physical, and functional problems experienced by many ICU survivors (20). Early mobility and in-hospital rehabilitation appears promising in available reports (18, 21, 22, 23). However, very few data exist to inform us regarding formal rehabilitation programs for general medical and surgical ICU survivors once discharged from the hospital and no studies have attempted cognitive rehabilitation either alone or in conjunction with the rehabilitation of other domains of functioning (24). In the absence of active recovery programs, patients often fail to recover optimally and may experience accelerated decline with far reaching effects for them, their families, and public health at large.

A critical evaluation of existing research led us to hypothesize that a rehabilitation approach combining cognitive, physical, and functional training could have enhanced effects related to the beneficial physiological effects of exercise on cognition (25, 26) (and potentially on the responsiveness to cognitive training) as well as the effects of functional training facilitating translation of newly acquired skills into daily life (27, 28). We hypothesized that in a cohort of ICU survivors, a “bundled” rehabilitation approach combining cognitive, physical, and functional rehabilitation could be developed and effectively delivered in the home using novel tele-video technology delivered via social workers and would result in greater improvement in cognition and functional outcomes in intervention than control participants. To begin the process of testing this hypothesis, we conducted a pilot, feasibility randomized controlled trial (RCT), employing a structured 12-week, in-home rehabilitation program, in a cohort of ICU survivors with cognitive and/or physical impairment, documented post-ICU stay and prior to hospital discharge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design Overview

In this randomized controlled trial of home-based cognitive, physical, and functional rehabilitation [The Returning to Everyday Tasks Utilizing Rehabilitation Networks (RETURN) Study] we assessed clinical outcomes in ICU survivors 3 months after discharge to home among patients originally hospitalized at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Settings and Participants

We recruited study participants at Vanderbilt University Medical Center between August 2008 and February 2009. Researchers at Vanderbilt University, Duke University, and the Nashville (Tennessee Valley) and Durham VA Medical Centers supervised the trial and institutional review boards (IRBs) approved the protocol.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible patients included adult (>18 years of age), English-speaking, medical intensive care unit (MICU) and surgical intensive care unit (SICU) patients enrolled in an NIH -sponsored observational cohort – the NIA-sponsored BRAIN-ICU cohort (5R01AG027472-05).

Exclusion criteria for the BRAIN-ICU Study were as follows: a). Cumulative ICU time >5 days in the past 30 days, not including the current ICU stay, b). Severe cognitive or neurodegenerative diseases that prevented a patient from living independently at baseline, including mental illness requiring institutionalization, acquired or congenital mental retardation, known brain lesions, traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular accidents with resultant moderate to severe cognitive deficits or ADL dependency, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, severe Alzheimer's disease or dementia of any etiology, c). ICU admission post cardiopulmonary resuscitation with suspected anoxic injury, d). An active substance abuse or psychotic disorder, or a recent (within the past 6 months) serious suicidal gesture necessitating hospitalization, e). Blind, deaf, or unable to speak English, f). Overly moribund and not expected to survive for an additional 24 hours and / or withdrawing life support to focus on comfort measures only, g). Prisoners, h). Patients who lived further than 200 miles from Nashville and who did not regularly visit the Nashville area, i). Patients who were homeless and had no secondary contact person available, j). The onset of the episode of respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock was > 72 hours prior to admission, k). Patients who had cardiac bypass surgery within the past 3 months (including index hospitalization).

Patients who met the inclusion criteria for BRAIN-ICU and, as such were potentially eligible for RETURN, were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: a) discharge planned to nursing home/rehabilitation center, b) the presence of both normal cognition and normal physical function at time of screening (i.e. at hospital discharge), c) lack of telephone service with an analog telephone line (required for telephonic and televideo interventions), d) lived outside a 125 mile radius (to limit the burden of travel on technicians providing rehabilitation). Eligibility criteria were changed during the trial to allow for the inclusion of participants who were discharged to a nursing home or rehabilitation center.

Enrollment Procedures

Eligible patients who consented to participate were screened by a physician (JC or DJ) immediately prior to hospital discharge using objective tests of cognitive and physical functioning [Delis-Kaplan Tower Test (TOWER)] (29) and the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) (30). Scores on the TOWER and TUG were considered “positive” (i.e., abnormal) if they were >1 SD below the norm referenced mean (suggestive of “abnormal” performance relative to the population at large). Patients earning “positive” scores on either the TOWER or the TUG (reflecting either cognitive and/or physical deficits) were immediately randomized. Patients achieving normal scores on both were excluded from further participation as they were not believed to need rehabilitation due to the absence of appreciable deficits. Screening took approximately 10 to 15 minutes per patient.

Randomization was done using a 2:1 randomization scheme (intervention vs. control) to maximize knowledge gained from the number of participants in the study’s intervention group. Permuted block randomization was employed, with block sizes of 3 and 6. Randomization was concealed via tri-folded randomization sheets placed in sealed opaque envelopes. Staff enrolling study participants were thus blinded as to which group the next eligible patient would be randomized.

Usual Care in the Control and Intervention Group

Participants in both the control and intervention groups were fully eligible for “usual care” rehabilitation-related interventions during and following hospitalization, as determined by their medical providers. The scope of “usual care” interventions employed with ICU survivors may include physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and nursing care, delivered to in-patient, out-patient, or home-health settings. Neither cognitive therapy nor speech therapy with a predominant cognitive focus is considered “usual care” among ICU survivors without frank neurologic injuries.

Description of the 3-Pronged RETURN Rehabilitation Protocol

The comprehensive, multicomponent, in-home rehabilitation program delivered to the intervention patients was developed with a specific focus on the remediation of characteristic deficits among ICU survivors (i.e., limitations in cognition (6, 7, 31), strength and endurance (17, 32) and functional ability (6, 17)). The 3 components were designed to supplement and reinforce one another. In particular, we hypothesized that aerobic exercise might amplify the effectiveness of cognitive training (27) and enhance physical function (27, 33), and that home-based functional training (27, 28, 34, 35) might potentiate the effects of exercise training on mobility confidence and physical function and help cognitively impaired persons incorporate acquired or re-acquired cognitive skills into daily life.

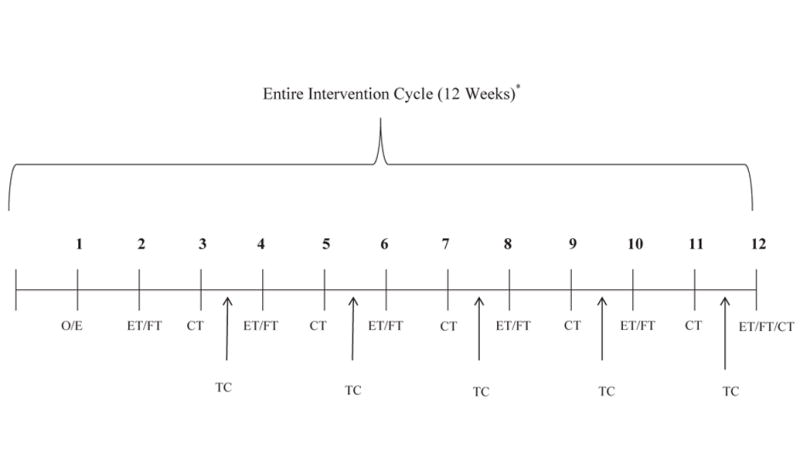

The rehabilitation intervention was provided over a 12-week period post-discharge in each patient’s home and integrated both traditional “face-to-face” interventions as well as novel telephonic and video-based interventions (Figure 1). It included a total of 12 visits - 6 in-person visits for cognitive rehabilitation and 6 televisits for physical and functional rehabilitation, each 60-75 minutes in length, with sessions following an alternating format (i.e., first cognitive then physical-functional and so on). Televisits used interactive 2-way videophones facilitated by an assistant in the home and/or were video recorded for subsequent review. Visits were supplemented with brief telephone calls by study personnel from relevant disciplines during alternate weeks. Participants completed a workbook between visits to help track compliance.

Figure 1. Intervention Timeline.

CT = cognitive therapy (GMT), ET = exercise training, FT = functional training, O/E = Orientation/Exercise, TC = therapy consultation. ET and FT interventions were delivered in tandem and cognitive therapy was generally delivered in a stand-alone fashion. Therapy consultations were done exclusively on the telephone and occurred between “in person” sessions, which a focus on providing support and reinforcement and on fostering treatment compliance with a focus on daily functioning.

The initial evaluation included videotaping specified functional mobility tasks (36) and any ongoing exercises, as well as the use of a self-report measure to obtain information of personal importance such as independence, difficulty and safety in daily tasks (37). Detailed protocols were developed for all visits and for cross-disciplinary skill reinforcement activities (available on request from the authors). Interdisciplinary communication occurred through weekly conference calls and use of a jointly accessible database. Intervention fidelity was assured by senior study staff (HH, MM, JJ, WE) through participation in weekly conference calls and periodic reviews of videotapes and televisits.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

The cognitive training was based on the Goal Management Training (GMT) protocol (38), a focused and theoretically derived stepwise approach to the rehabilitation of executive function shown to be effective in preliminary studies with other populations (39, 40), which we adapted for use in the home. The purpose of GMT is to improve a patient’s executive function (among the most frequent and most profoundly affected neuropsychological domains following critical illness) (41-43) by increasing goal directed behavior and helping patients (a) learn to be reflective (to “stop and think” about consequences of decisions) prior to making decisions and executing specific tasks, and (b) achieve success in engaging complex tasks by dividing them into manageable units, so as to increase the likelihood that these tasks will be completed. The GMT sessions built on one another to increase the “dose” of rehabilitation delivered. At the start of each session, the goals and rationale of the particular module in question were explained. The participants carried out a series of increasingly challenging cognitive tasks associated with the themes of each module and completed relevant homework between cognitive training sessions. Cognitive training was delivered in the home by a master’s level psychology technician (VMA) who was supervised by a licensed neuropsychologist (JCJ).

Physical Rehabilitation

The exercise intervention was based on prior work by Morey et al, a co-investigator on RETURN, which showed improved physical function with telephone counseling that promoted home-based endurance and strength exercises (44). The exercise intervention was delivered by a remote a bachelor’s level exercise trainer (NW) supervised by a doctoral level exercise physiologist (MM) who was communicating in “real time” with the patient via teletechnology and assistance of a trained social worker in the home (LBD). Physical activity was objectively evaluated at study inception and progressively increased according to the patient’s abilities. Exercise prescriptions were individually tailored (“dosed”) to correspond to functional status levels and primarily targeted lower extremity function and endurance using exercises that could be easily performed in the home (e.g., chair stands, toe rises, stair climbing, walking, etc.) The exercise intervention included 6 televideo visits (one every other week) along with 6 motivational telephone calls. Each call followed a structured protocol to assess previously prescribed exercises, explore and address potential barriers to exercise, motivate and encourage continued exercise and advance previous exercises as needed. In between visits and calls, the patients carried out exercises independently.

Functional Rehabilitation

Functional training consisted of 4 televisits with an occupational therapist (CS) who was communicating in “real time” with the patient via teletechnology and assistance of a trained social worker in the home (LBD), 4-6 supplementary telephone calls, and participant homework between sessions. The functional training was based on prior work by Hoenig et al (36), co-principal investigator on RETURN and Gitlin et al (27, 28) which used an “environmental approach” to resolve functional problems (i.e., change the environment or change the way the person interacts with the environment), and refined for this study by 2 of the coauthors (HH, CS). Two tactics were used for the functional training:

Education ─ helping the participant understand the relationship between “person” (i.e., their skills and abilities), “environment” (i.e., equipment, built and non-built environment), and “activity” (i.e., specific tasks).

“Action Plan” Development ─ utilized for individual tasks, based on a combination of the therapist input and participant homework. Homework focused on specific tasks prioritized by the study participant, with worksheets designed to foster problem-solving using the “Person-Environment-Activity” approach and application of the principles taught in the cognitive training and the physical skills developed through the exercise training to the prioritized activities.

Outcome Measures

We assessed each patient’s cognitive, physical, and daily higher order functioning (ability to engage complex daily tasks) at the time of enrollment in the study (representing a pre-intervention “baseline”) prior to hospital discharge and again at the completion of the 12-week intervention (i.e., 3 months following hospital discharge from Vanderbilt University Medical Center). Assessments were conducted by trained study staff (including physicians in training, master’s level psychologists, and research coordinators) that were unaware of and blinded to randomization allocation. Primary and secondary outcomes were assessed.

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest were the Tower Test (TOWER) (29) and the Timed Up and G0 (TUG) (26). The TOWER is a timed objective measure of executive cognitive function that assesses ability to plan and strategize efficiently by requiring participants to move disks across 3 pegs until a tower is built, using the fewest number of moves possible while adhering to 2 rules – 1) a larger disk cannot be placed on top of a smaller disk and 2) disks must be moved one at a time, using only one hand (45). The Tower is widely employed in investigations of executive dysfunction and has adequate psychometric properties including inter-class correlations of between .62 and .78 (45). It has consistently been shown to be sensitive to the detection of brain damage, particularly frontal lobe dysfunction. Scores in the “normal” range on Tower subtests (such as the Achievement Score, our primary outcome measure) range from 7 to 13 (46, 47). The TUG is a timed objective measure of physical functioning and mobility that requires an individual to stand up from a chair, walk 10 feet, return to the chair, and sit down. The TUG has been extensively studied with medical and rehabilitation populations and possesses high reliability (ICC from 0.88 to 0.95) and construct validity, while effectively distinguishing between individuals at risk and not at risk for falls. “Normal” performance for the TUG varies widely, but scores of greater than 13.5 seconds are believed to reflect significant problems (30, 48).

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes measures were also employed and included measures of cognition (the Mini-Mental State Examination, the Dysexecutive Questionnaire), physical functioning (the Activities Balance and Confidence Scale) and daily functioning (the Functional Activities Questionnaire and the Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale). The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) (49), is a brief objective screening tool evaluating general cognition used extensively in clinical and investigative settings. It has adequate internal consistent consistency (alpha = 0.78), excellent test-retest reliability (r > 0.75), and adequate inter-rater reliability, as well as good sensitivity and specificity, particularly when employed with individuals with appreciable levels of cognitive impairment (50,51). The Dysexecutive Questionnaire (DEX) (42) is a rating tool with participant and surrogate forms, which assesses behaviors mediated by executive functioning such as decision-making, impulsivity, social appropriateness, and planning for the future. Though the psychometric properties of the DEX have been relatively little studied, recent investigations have demonstrated it to be a reliable measure (r = 0.85) (52).

The Activities and Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale is a 16-item self-report measure which assesses an individual’s self-confidence in their ability to safely engage in activities requiring balance such as walking down stairs and getting on and off of an escalator (45). The ABC Scale has high test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.92), high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96) and good construct validity, as reflected in correlations with other scales such as the Physical Self-Efficacy Scale (r = 0.49) and the Falls Efficacy Scale (r = 0.84) (53).

The Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) (54), is a self-report measure assessing instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS) such as cooking, driving, and managing finances (all complex activities requiring higher-order abilities). The FAQ has strong psychometric properties including excellent inter-rater reliability (0.97), while correlating strongly (0.72) with other IADL measures such as the Lawton and Brody’s IADL, though the scale has been shown to be ineffective at differentiating between those with and without dementia (54-56). The Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale (57) is a 6-item self-report measure of basic capacities required for independent functioning such as bathing, dressing, transferring, and toileting. Despite being a widely used measure of physical functioning and disability, little information exists regarding the reliability and validity of the Katz, though it has been shown to be sensitive and specific in predicting mortality as well as sensitive to change over time (58, 59).

For a detailed description of approaches related to scoring and interpreting our primary and secondary outcome measures, refer to Table 2, Legend.

Table 2.

| Test | N | Baseline

|

3-Month Follow-up

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control N = 8 |

Intervention N = 7 |

P-Value | Control N = 8 |

Intervention N = 7 |

P-Value | ||

| Tower1 | 15 | 7.5 [4.5- 9.0] | 8.0 [6.5- 10.0] | 0.37 | 7.5 [4.0- 8.5] | 13.0 [11.5- 14.0] | <0.01 |

| TUG2 | 15 | 15 [12- 20] | 18 [15-20] | 0.47 | 10.2 [9.2 -11.7] | 9.0 [8.5-11.8] | 0.51 |

| Katz ADL3 | 15 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||||

| Little/no dep. | 75% (6) | 71% (5) | 75% (6) | 100% (7) | |||

| Mod/severe dep. | 25% (2) | 29% (2) | 25% (2) | 0% (0) | |||

| FAQ4 | 15 | 7.0 [1.5- 14.2] | 0.0 [0.0- 4.0] | 0.14 | 8.0 [6.0- 11.8] | 1.0 [0.0 - 2.5] | 0.04 |

| ABC Scale5 | 15 | 54 [28- 75] | 68 [36-81] | 0.58 | 83 [38- 91] | 82 [78- 89] | 0.35 |

| DEX6 | 15 | 27.0 [13.5- 31.0] | 13.0 [8.0- 15.0] | 0.12 | 16.0[7.8-19.2] | 8.0 [6.0- 13.5] | 0.74 |

| MMSE7 | 15 | 27.0 [22.5- 28.2] | 28.0 [25.0- 29.0] | 0.54 | 26.5 [24.8-28.5] | 30.0 [29.0-30.0] | 0.25 |

Median [interquartile range] unless otherwise specified.

Participants were evaluated with cognitive, physical, and functional assessment measures at the time of enrollment (prior to randomization). Their scores on these measures at enrollment reflect a “pre-intervention” baseline against which their scores at 3-month follow-up may be compared.

Our table reflects an N of 15, including 8 controls and 7 in the intervention group. Though a total of 9 individuals participated in the study intervention (GMT), complete data – including co-primary outcomes, the TUG test and Tower test - were obtained on 7 subjects.

Abbreviations/Definitions

Tower refers to the Tower Test Achievement Score, the primary outcome on the Tower Test, which assesses overall executive functioning ability on a test of planning and strategy. Scores range from 1 to 19, with higher scores reflecting better performance.

TUG refers to the Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test, a test that assesses ambulation ability. Scores refer to time in seconds and higher scores reflect worse performance.

Katz ADL refers to the Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale, a self-reported measure of basic activities required for independent functioning. Overall scores on the Katz ADL range from 0 to 18 but we analyzed scores in a binary fashion by creating 2 categories of outcomes - little to no dependency (0 to 1, indicative of no more than partial dependency in 1 of 6 ADL categories) vs. moderate to severe dependency (>1, indicative of at least partial dependency in at least 2 of 6 ADL categories).

FAQ refers to the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), a 10 item self-report measure of complex instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Scores range from 0 to 30 and higher scores reflect poorer performance.

ABC Scale refers to Activities Balance and Confidence (ABC) Scale, a brief measure that rates an individual’s confidence in their balance. Higher scores reflect greater confidence in balance and reflect a percentage (0% to 100%).

DEX refers to the Dysexecutive Questionnaire (DEX), a brief self-report measure that rates behavioral markers of executive functioning. Scores range from 0 to 80 and higher scores reflect poorer functioning.

MMSE refers to the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), a brief objective measure of overall cognitive ability. Scores range from 0 to 30 and higher scores reflect better functioning.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses regarding socioeconomic characteristics, baseline health conditions, and severity of illness were done comparing intervention and control groups using Mann-Whitney U-tests for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables. Linear regression was employed to examine differences in follow-up assessment scores on primary and secondary outcome measures between treatment groups while adjusting for baseline treatment scores. Adjusted treatment effects are the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the treatment coefficient in the ANCOVA models. They describe the difference in the three-month measurement for the intervention group as compared to the control group, while adjusting for baseline measurement. Logistic regression was also employed to analyze data from our dichotomous Katz ADL outcome. Due to the preliminary nature of this investigation and its primary goals, which included hypothesis generation, evaluation of feasibility, and assessing proof of principle, a formal power analysis and was not used to determine the study’s sample size, and most of the reported outcomes are underpowered.

Statistical analyses were done using R version 2.12. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00715494).

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author, Dr. Ely, and Dr. Hoenig, had full access to the data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Participants

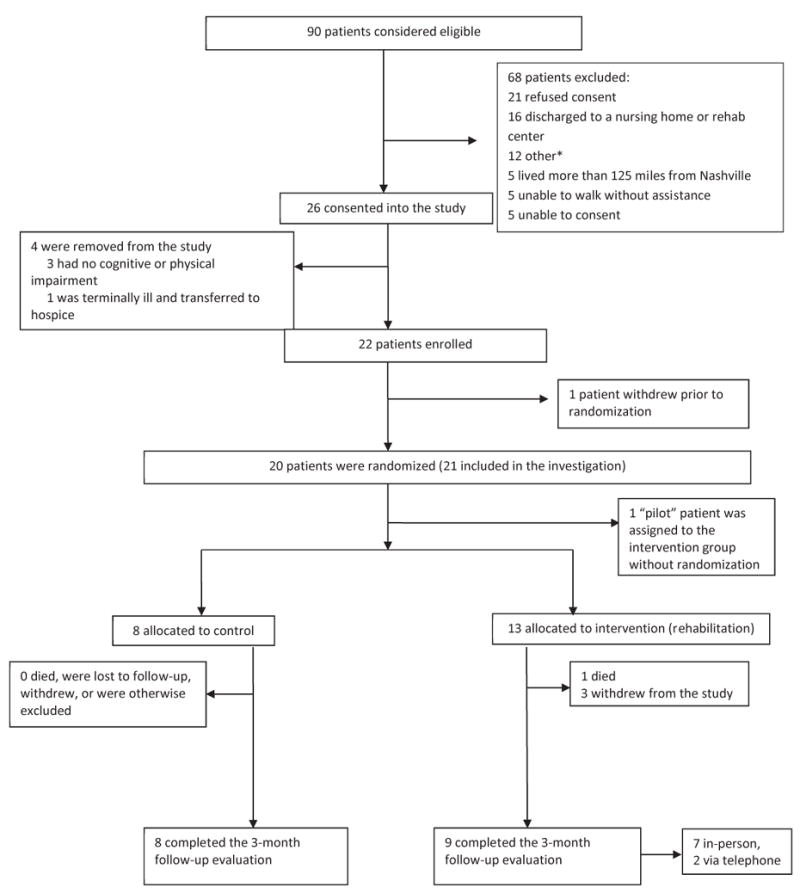

A total of 90 subjects were considered for enrollment between August 2008 and February 2009 (Figure 2). We enrolled a total of 22 participants. A total of 26 were consented into the investigation – of these, 4 were withdrawn from the investigation and never enrolled as they did not meet relevant enrollment criteria. Among the 22 enrolled, 1 withdrew immediately after enrollment and prior to randomization. 20 participants were randomized (8 to the control group and 12 to the intervention group). 1 participant (the study’s initial, pilot patient) was assigned to the intervention group and not randomized. No participants withdrew from the control group.

Figure 2. Flow chart of recruitment and study participation.

Other exclusions: 2 discharged to hospice, 2 could not be reconsented due to unavailability of study staff, 2 were not consented for the parent study (BRAIN) prior to discharge, 1 patient was uncooperative and refused assessments, 1 patient was violent and transferred to a psychiatric hospital, 1 patient lived in an environment unsafe for home visits.

With respect to key baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, participants were generally similar, though certain differences were observed (Table 1). Severity of illness, as measured via the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation Score – II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure (SOFA) scores were slightly higher (though not statistically significantly so) in control versus intervention patients, and control patients suffered from a larger number of medical comorbidities (as measured by overall scores on the Duke Comorbidity Index). Control patients also experienced longer ICU hospitalizations and greater duration of mechanical ventilation, which though not statistically significantly different may have been clinically significant. Scores on relevant outcome measures at a baseline (pre-intervention) assessment were not statistically significantly different between groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of RETURN Participants at Enrollment*

| Control N = 8 |

Intervention N = 13 |

Complete Intervention Patient N = 7 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50 [46- 69] | 47 [41- 59] | 44 [41- 63] |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 62% (5) | 38% (5) | 71% (5) |

| Male | 38% (3) | 62% (8) | 29% (2) |

| Race | |||

| White | 88% (7) | 92% (12) | 86% (6) |

| African-American | 12% (1) | 8% (1) | 14% (1) |

| Education (years) | 12.0 [11.8- 12.0] | 12 [12- 16] | 12 [12- 16] |

| Admission Diagnosis | |||

| Sepsis/ARDS1 | 25% (2) | 31% (4) | 29% (2) |

| Acute MI2 | 0% (0) | 8% (1) | 14% (1) |

| COPD/Asthma3 | 0% (0) | 8% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Renal Failure | 0% (0) | 8% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Airway Protection | 0% (0) | 8% (1) | 14% (1) |

| Cardiogenic Shock/CHF4 | 12% (1) | 15% (2) | 14% (1) |

| Cirrhosis | 12% (1) | 8% (1) | 14% (1) |

| ENT Surgery5 | 12% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Transplants (excl Liver) | 12% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Hepatobiliary Surgery | 12% (1) | 15% (2) | 14% (1) |

| Pulmonary | 12% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| ICU Type | |||

| Medical | 50% (4) | 69% (9) | 57% (4) |

| Surgical | 50% (4) | 31% (4) | 43% (3) |

| APACHE II6 | 25.5 [19.5- 33.0] | 23 [19- 27] | 21.0 [18.5- 27.5] |

| SOFA7 | 10.5 [6.8- 12.0] | 9 [7- 11] | 11.0 [9.5- 13.0] |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 11.5 (9.2, 14.4) | 11 (6.2, 13) | 6.2 (3.7, 10.1) |

| ICU LOS (days) | 5.8 [4.3- 7.0] | 3 [2.1- 7.9] | 2.1 [2.0- 3.5] |

| Vent Duration (days) | 4.8 [2.5-5.8] | 1.9 [0.8-3.2] | 1.4 [0.4-2.6] |

| Discharge Disposition | |||

| Home | 88% (7) | 92% (11) | 100% (7) |

| Nursing Home | 0% (0) | 8% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Rehabilitation Facility | 12% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Charlson Co-Morbidity | 2.00 [0.75- 6.00] | 2.00[0.00-3.00] | 2.00 [0.50- 3.00] |

| Duke Overall | 3.5 [2.8- 6.8] | 2.0 [2.0- 3.0] | 2.0 [2.0- 3.0] |

| Duke Limitation | 3.5 [2.0- 4.5] | 2.0 [1.0- 3.0] | 2.0 [1.5- 2.5] |

Median [interquartile range] unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: ARDS = Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Acute MI = Acute Myocardial Infarction

COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

CHF = Congestive Heart Failure

ENT Surgery = Ear Nose and Throat Surgery

APACHE-II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Duke Overall and Duke Limitation refer to Duke Comorbidity Index (DCI) – The “overall” score on the DCI reflects the total number of diseases experienced by a study subject. The “limitation” score refers to the strength of an individual’s perception that their conditions are limiting. In both cases, higher scores are worse.

One adverse event was reported – a participant in the intervention group experienced a minor ankle sprain while participating in a walking exercise. He did not require formal medical attention and was fully able to participate in exercise interventions at the next visit.

Rehabilitation Following Hospital Discharge (Control and Intervention Groups)

A similar percentage of participants in intervention versus control groups (85% vs. 88%) were discharged home versus to a nursing home or formal rehabilitation setting (p = 0.85). The extent to which participants engaged in outpatient rehabilitation following discharge is unknown, as we were unable to obtain this information in over half of all participants.

Cognitive Function Outcomes

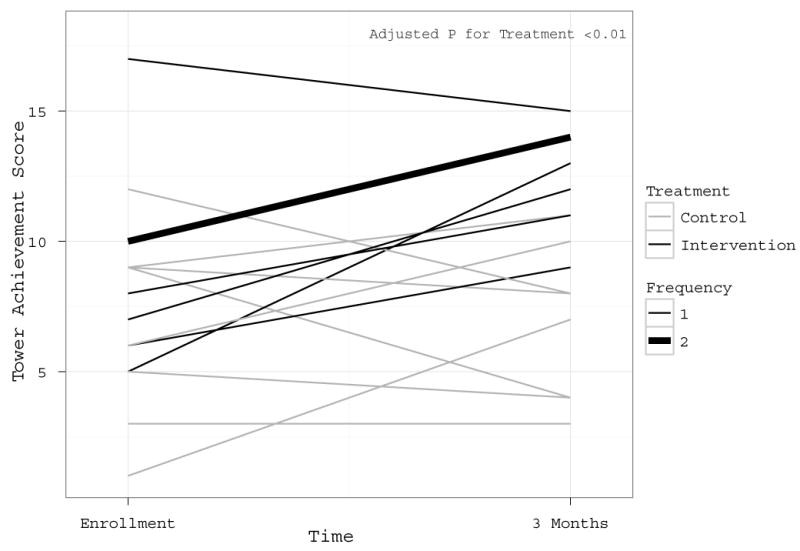

Intervention and control group participants performed similarly at study enrollment on the primary cognitive outcome measure, the TOWER (Table 2). At 3-month follow-up, a significant difference between groups was observed, with the intervention group patients earning higher scores than controls (3-months TOWER - Median/IQR - 13.0 [11.5 to 14.0] vs. 7.5 [4.0 to 8.5], adjusted treatment effect 5.0 [95% CI, 2.5 to 7.5], adjusted p<0.01) (Table 2, Figure 3). With regard to secondary measures of cognition, both groups performed similarly to one another on the DEX and the MMSE at baseline and 3-month follow-up (Table 2).

Figure 3. Comparison of Tower Test Scores at Enrollment vs. 3-Month Follow-Up.

Higher scores reflect better executive functioning ability. The graph reflects the findings that intervention patients characteristically improved in their Tower Test performance of executive function as compared to control patients, as shown in Figure 3 (P<0.01). In the legend, patients in the treatment group are represented by black lines and patients in the intervention group are represented by gray lines. In the legend, the Frequency notation indicates that all thin lines represent scores from individual patients, while the single thick gray line represents 2 patients who had identical scores at enrollment and 3 months in the intervention group. The p-value for treatment is from a linear regression model with three-month Tower scores as its outcome as an independent variable, adjusting for baseline Tower.

Physical Functioning

On the TUG (lower scores are better), intervention and control participants earned similar scores at baseline (prior to intervention) (18 [15-20] vs. 15 [12-20]) and at 3-months (9.0 [8.5 vs. 11.8] vs. 10.2 [9.2-11.7]). Although the intervention group improved slightly more than the control group these differences were not statistically significance (adjusted treatment effect -1.1 [95% CI-4.1, 2.0], adjusted p=0.51) (Table 2). Similarly, ABC scores of self-efficacy did not differ between the two groups at baseline (68 [36-81] vs. 54 [28-75], p=0.58) nor at 3-months (82 [78-89] vs. 83 [38-91], p=0.35)

Functional Ability

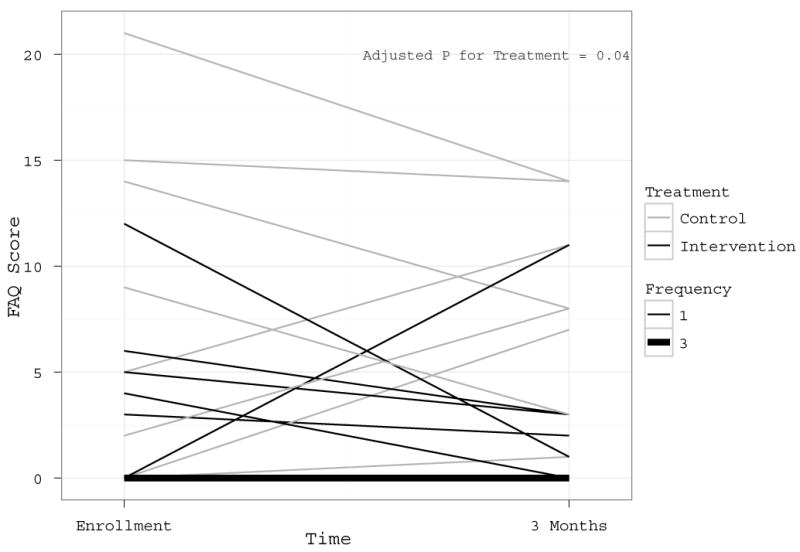

No statistically significant differences were noted in baseline IADL performance (prior to intervention) between intervention and control group participants (Table 2). At 3-month follow-up, a statistically significant difference was observed between groups (Figure 4), with intervention participants demonstrating better IADL performance vs. controls (lower scores are better) (3-month FAQ 1.0 [0.0 – 2.5] vs. 8.0 [6.0 – 11.8], p = 0.04), supported by an ANCOVA analyses showing an adjusted treatment effect of -4.7 (95% CI -8.7, -0.6). With regard to ADLs, scores on the Katz ADL scale dichotomized into categories “little or no dependency” and “moderate to severe dependency” were similar between groups at enrollment (29% of intervention participants with “moderate to severe dependency” vs. 25% of controls, p=0.88). At 3-month follow-up, none of the intervention participants reported experiencing “moderate to severe dependency,” while “moderate to severe dependency” was reported by a quarter (25%) of those in the control group, though after adjusting for baseline values, these differences were not statistically significant (adjusted p=0.78).

Figure 4. Comparison of FAQ Scores at Enrollment vs. 3-Month Follow-Up.

Lower scores reflect better instrumental activities of daily living ability (IADLs). The graph reflects the findings that while statistically significant as shown in Figure 4 (P=0.04), the differences in improvement in IADLs in treatment versus control patients are modest and not consistent in all patients. In the legend, patients in the treatment group are represented by black lines and patients in the intervention group are represented by gray lines. In the legend, the Frequency notation indicates that all thin lines represent scores from individual patients, while the single thick gray line represents 3 patients who had identical scores at enrollment and 3 months in the intervention group. The p-value for treatment is from a linear regression models with three-month FAQ score as its outcome and treatment group as an independent variable, adjusting for baseline FAQ score.

Characteristics of Participants Who Withdrew

Of the 21 patients randomized, a total of 3 withdrew – all in the intervention arm of the investigation. Reasons these patients withdrew are as follows: 1) A patient reported that study participation was “inconvenient” and opted to withdraw; 2) A patient withdrew for “personal reasons,” stating they were unrelated to the study; 3) A patient withdrew due to significant medical issues that resulted in 3 rehospitalizations within a month of discharge. The baseline scores earned by those who withdrew on key outcome measures were similar to those earned by the intervention group participants who remained in the study.

DISCUSSION

Using social workers/technicians and telemedicine to deliver a 3-pronged rehabilitation program to general medical and surgical ICU survivors in their homes resulted in superior executive functioning as compared to usual care in this small pilot feasibility randomized trial. Intervention group participants also reported improvements in the performance of daily IADLs (managing money, making travel arrangements, following complex instructions, etc). The benefits found via this rehabilitation program together with the novel components of delivery (in-home using social workers and technicians as well as telemedicine), can serve as a template by which to pave a road to future investigations and eventually a change in policy and practice towards survivors of critical care.

Our findings are novel in that they demonstrate these improvements in a new population of cognitively impaired general medical and surgical ICU survivors. Prior cognitive rehabilitation studies have shown promising results, yet these studies have not focused on ICU survivors (60-62). Among the largest investigations (n=49) of the cognitive rehabilitation tool used for our study to date (i.e., GMT), Levine and colleagues reported that participants receiving GMT demonstrated improvements in “executive deficits” via a self-rating scale (38). Our findings extend this previous work (63-65) in demonstrating that our participants receiving cognitive rehabilitation improved on both objective cognitive testing (i.e. the TOWER) and subjective self-perception of complex daily functioning (i.e. the FAQ). Participants did not improve on the DEX, which differs from the FAQ in that it largely assesses emotional characteristics and behaviors such as apathy, disinhibition, and degree of social appropriateness (66). In assessing behavioral and emotional functioning, the DEX is also distinct from the TOWER, which, in contrast, shares properties with the FAQ, which is comprised of items that explicitly require planning ability.

The improvements in cognitive performance and generalization of skills into daily life may have been due to potentiation achieved by our multi-component intervention aimed towards both the body and brain deficits. The effect sizes of our intervention (TOWER 2.25, FAQ 1.52) are substantially greater than those seen in other studies (e.g., 0.26-0.48 on tests of memory and reasoning, 0.12 for IADLs in a large study by Ball et al (67) and 0.73-0.74 with simulated real life tasks in the largest study of GMT to date (38)). Based on prior research (25, 68), we hypothesized a priori that the exercise training we delivered might potentiate the efficacy of the cognitive training and that the exercise and functional training components of our intervention might help new cognitive skills generalize into daily life (27, 28), but this must be tested further. In addition to the evidence-based rationale for these specific components, there is a substantive body of literature in rehabilitation medicine showing that patients with neurologic injury experience better functional outcomes with multidisciplinary rehabilitation (36)(69-71). Our results are consistent with this body of literature and extend it by applying these principles to a novel population via a novel approach incorporating tele-technology, with promising results.

Our investigation cannot determine the mechanisms contributing to improvements in the intervention group. Mainly this study establishes feasibility and sets the stage for future studies designed to understand the efficacy of physical and cognitive rehabilitation as individual interventions post ICU care as well as possible potentiating or synergistic effects of both together. The benefits of vigorous physical exercise on cognitive functioning have been widely demonstrated in the context of RCTs with other populations (72, 73). Interestingly, evidence suggests that that the cognitive domain most significantly affected by exercise is executive function (69). Although mechanisms linking exercise and improved neuropsychological functioning are not fully elucidated, evidence from animal models shows that exercise decreases amyloid load, enhances both hippocampal and parietal cortical cholinergic function, and increases levels of brain derived neurotrophic factors (74-76).

Despite the effects of the intervention on cognition and daily functioning, we did not find statistically significant differences between groups in measures of physical functioning. This could be due to sample size and Type II error. Likewise, it could be that individuals in the control group received exercise training independently (e.g. continuing to perform exercises they learned during in-hospital physical therapy) or that the outcome measures of physical function we employed (e.g. TUG and ABC tests) were relatively insensitive to the effects of our intervention. Alternatively, study participants might require interventions of a greater magnitude than was employed to facilitate significant improvement in physical functioning in a 3-month time frame. In any event, we were primarily interested in exploring feasibility in this pilot trial, and it is worth noting that a sample size of 22 provides 80% power with a two-tailed alpha of 0.5 to detect an effect size of 1.3. We had an effect size of 0.57 on the ABC Scale, which meant our study power was only 24% to reject the null hypothesis.

Rehabilitation researchers have recently begun investigating use of teletechnology as a way to provide expert services to persons who otherwise lack access to sophisticated rehabilitation expertise. This is the first application of such technology to ICU survivors. In the context of our investigation, we utilized tele-visits (with interactive 2-way video phones) to augment “face-to-face” interaction and videotaped patients engaged in physical and functional activities in their homes (36). The incorporation of teletechnology into our multi-component rehabilitation intervention had two primary purposes. First, it allowed physically debilitated patients, who were unable to drive or travel an opportunity to receive treatment in their own homes, ensuring high compliance. Second, it extended the “reach” of specialists at the large medical centers by allowing them to direct and adapt the rehabilitation treatments of rurally located patients in “real time” through telephone or video-based communication supported by the more widely available social workers and psychology technicians, thus increasing the exportability of the intervention into patients’ homes. Although we did not formally study issues related to “cost” in our current study, it seems likely that the model of rehabilitation we employed (using social workers and psychology technicians) is less expensive than models involving more substantial reliance on specialists such as physiatrists or neuropsychologists, although this is speculative. Incidentally, it may be the case that approaches such as the one we utilized could be not only less expensive than alternatives but could result in significant cost savings, through improving cognitive functioning and higher order functional abilities, improvements which in numerous investigations have been shown to translate into better employment outcomes and increased independence.

In addition to the pilot, feasibility sample size and the intended bundling of the intervention components, both of which will be easily addressed in subsequent studies, our investigation had numerous limitations and strengths. Our small sample size (drawn from a relatively much larger cohort of ICU patients) raises potential questions about degree to which study participants are representative of the overall population of critically ill adults, though from purely demographic and clinical perspectives, they appear quite typical. We had a relatively high proportion of drop-outs in the intervention group, although demographically these individuals were similar to the individuals who remained in the study. While it is possible these patients would have reduced our effect size, it is at least as likely that the patients dropping out were primed for great gains from the rehabilitation protocol. Additionally, the differences in specific demographic and hospital/illness related variables (e.g. duration of hospitalization, duration of mechanical ventilation, severity of illness), particularly between controls and “intervention completers”, tended to favor the intervention group. Though these individuals were critically ill, they were younger, with less complicated and more abbreviated treatment courses both in the ICU and the hospital than their counterparts. As such, it is possible that the intervention group was uniquely predisposed to benefit from GMT and associated therapies. Though similar percentages of control versus intervention participants were discharged home from the ICU, details about their involvement in outpatient rehabilitation remain unclear as we were unable to obtain this information in approximately half of all participants. As noted elsewhere, we did not attempt to quantify the costs (or the potential cost-savings) of our intervention and acknowledge that this is a limitation and an issue that should be carefully and comprehensively studied in future investigations.

Strengths of our study include assessing multiple functional domains both objectively and subjectively, and most importantly, the use of a highly novel approach to rehabilitation previously untested in general medical and surgical ICU survivors. This multidisciplinary intervention, relying on interactions between expert providers and social workers via tele-technology, enabled outreach to patients from widely dispersed areas where rehabilitation expertise often is lacking (77).

The cognitive, physical, and functional problems experienced by ICU survivors are considerable and increasingly well documented. In theory, it may be possible one day to modify the ICU-related risk factors (e.g., overuse of potent sedatives and prolonged immobility time) independently associated with these adverse outcomes and reduce survivors’ deficits. In parallel, it is vital to continue development and investigation of multi-component rehabilitation interventions as an aid to accelerate recovery and assist patients in returning to their premorbid level of functioning. Our study represents an initial effort at cognitive and physical rehabilitation supported by teletechnology and a social worker or psychology technician to enable delivery in the patient’s home with maximum future applicability. These data provide preliminary evidence that the ICU-associated cognitive injury, which is common and debilitating in large numbers of survivors of critical illness, can be addressed through active rehabilitation efforts. These active rehabilitation efforts, directed via structured brain and body activities, may be effective in individuals following intensive care and should be subjected to extensive future study.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Dr. Hoenig received an AFAR Beeson Award. The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen GL, McGee M, Binkley J. Nutrition in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:313–334. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DS, et al. Long-term Cognitive Impairment and Functional Disability Among Survivors of Severe Sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, et al. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R6. doi: 10.1186/cc8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schelling G, Stoll C, Haller M, et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:651–659. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Pope D, et al. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:50–56. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9708059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothenhausler HB, Ehrentraut S, Stoll C, et al. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association Between Acute Care and Critical Illness Hospitalization and Cognitive Function in Older Adults. JAMA. 2010;303:763–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazquez Mata G, Rivera Fernandez R, Gonzalez Carmona A, et al. Factors related to quality of life 12 months after discharge from an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1257–1262. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuokko H, Morris C, Ebert P. Mild cognitive impairment and everyday functioning in older adults. Neurocase. 2005;11:40–47. doi: 10.1080/13554790490896802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozge C, Ozge A, Unal O. Cognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPD. Behav Neurol. 2006;17:121–130. doi: 10.1155/2006/848607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali NA, O'Brien JM, Jr, Hoffmann SP, et al. Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:261–268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens RD, Marshall SA, Cornblath DR, et al. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S299–S308. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens RD, Dowdy DW, Michaels RK, et al. Neuromuscular dysfunction acquired in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1876–1891. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA. 2008;300:1685–1690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher SN, Kennedy DD, Ghosh IR, et al. Persistent neuromuscular and neurophysiologic abnormalities in long-term survivors of prolonged critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1012–1016. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000053651.38421.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehabiliation after Critical Illness. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guideline. 2009;83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2238–2243. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2499–2505. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott D, McKinley S, Alison JA, et al. Health related quality of life and physical recovery after a critical illness: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical rehabiliation program. Critical Care. 2011;15:R142. doi: 10.1186/cc10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer AF, Erickson KI, Colcombe SJ. Exercise, cognition, and the aging brain. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1237–1242. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00500.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Dennis MP, et al. Maintenance of effects of the home environmental skill-building program for family caregivers and individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:368–374. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, et al. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS): Examiner's manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed Up and Go: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. JAGS. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, et al. Two-Year Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolton CF. Neuromuscular manifestations of critical illness. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:140–163. doi: 10.1002/mus.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keysor JJ, Jette AM. Have we oversold the benefit of late-life exercise? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M412–M423. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.m412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, et al. A prehabilitation program for physically frail community-living older persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:394–404. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanford JA, Griffiths PC, Richardson P, et al. The effects of in-home rehabilitation on task self-efficacy in mobility-impaired adults: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1641–1648. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoenig H, Sanford JA, Butterfield T, et al. Development of a teletechnology protocol for in-home rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:287–298. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.07.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersson I, Lilja M, Hammel J, et al. Impact of home modification services on ability in everyday life for people ageing with disabilities. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:253–260. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine B, Stuss DT, Winocur G, et al. Cognitive rehabilitation in the elderly: effects on strategic behavior in relation to goal management. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:143–152. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine B, Robertson IH, Clare L, et al. Rehabilitation of executive functioning: An experimental-clinical validation of Goal Management Training. Journal of the Inernational Neuropsychological Society. 2010;6:299–312. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700633052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hooren SA, Valentijn SA, Bosma H, et al. Effect fo a structured course involving goal management training in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;65:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sukantarat KT, Burgess PW, Williamson RC, et al. Prolonged cognitive dysfunction in survivors of critical illness. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christie JD, et al. Validity of a brief telephone-administered battery to assess cognitive function in survivors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;169:A781. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones C, Griffiths RD, Slater T, et al. Significant cognitive dysfunction in non-delirious patients identified during and persisting following critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:923–926. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morey MC, Peterson MJ, Pieper CF, et al. The Veterans Learning to Improve Fitness and Function in Elders Study: a randomized trial of primary care-based physical activity counseling for older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1166–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. D-KEFS Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psych Corp; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y. Attention, frailty, and falls: the effect of a manual task on basic mobility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiat Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pangman VC, Sloan J, Guse L. An examination of psychometric properties of the Mini-Mental State examination and the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination: Implications for clinical practice. Applied Nursing Research. 2000;13:209–213. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2000.9231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bodenburg S, Dopslaff N. The Dysexecutive Questionnaire Advanced: Item and Test Score Characteristics, 4-Factor Solution, and Severity Classification. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;196:75–78. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815faa2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–M34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jette AM, Harris BA, Cleary PD, et al. Functional recovery after hip fracture. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1987;68:735–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420:853–859. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niessner A, Steiner S, Speidl WS, et al. Simvastatin suppresses endotoxin-induced upregulation of toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fong TG, Jones RN, Rudolph JL, et al. Development and Validation of a Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool: The Sweet 16. Arch Intern Med. 2010;171:432–437. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burke WH, Zencius AH, Wesolowski MD, et al. Improving executive function disorders in brain-injured clients. Brain Inj. 1991;5:241–252. doi: 10.3109/02699059109008095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawson MJ, Rice DN. Effects of training in use of executive strategies on a verbal memory problem resulting from closed head injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11:842–854. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cicerone KD, Levin H, Malec J, et al. Cognitive rehabiliation interventions for executive function: moving from bench to bedside in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:1212–1222. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wykes. Cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gehring K, Sitskoorn MM, Gundy CM, et al. Cognitive rehabiliation in patients with gliomas: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;27:3712–3722. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gouillet J, Soury S, Lebornec G, et al. Rehabiliation of divided attention after severe traumatic brain injury: a randomised trial. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20:321–339. doi: 10.1080/09602010903467746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson BA, Alderman N, Burgess PW, et al. Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS) San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prvu Bettger JA, Stineman MG. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabiliation services in postacute care: state of the science. A review Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2007;88:1526–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grasso MG, Troisi E, Rizzi F, et al. Prognostic factors in multidisciplinary rehabiliation treatment in multiple sclerosis: an outcome study. mult scler. 2005;11:719–724. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1226oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murie-Fernandez M, Irimia P, Martinez-Vila E, et al. Neuro-rehabiliation after stroke. Neurologia. 2010;25:189–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Controlled Trial. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mead GE, Greig CA, Cunningham I, et al. Stroke: a randomized trial of exercise or relaxation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:892–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adlard PA, Perreau VM, Pop V, et al. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load ina transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lino MM, Vaillant C, Orolicki S, et al. Newly generated cell are increased in hippocampus of adult mice lacking a serine protease inhibitor. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pedersen BK, Pedersen M, Krabbe KS, et al. Role of exercise-induced brain-derived neurotrophic factor production in the regulation of energy hhomeostasis in mammmals. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:1153–1160. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.048561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson RD, Lewis SA, Murray PK. Trends in the rehabilitation therapist workforce in underserved areas: 1980 - 2000. J Rural Health. 2009;25:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]