Abstract

Background

The possible relationship between psoriasis and coeliac disease (CD) has been attributed to the common pathogenic mechanisms of the two diseases and the presence of antigliadin antibodies in patients has been reported to increase the incidence of CD.

Objective

The aim of this report was to study CD-associated antibodies serum antigliadin antibody immunoglobulin (Ig)A, IgG, anti-endomysial antibody IgA and anti-transglutaminase antibody IgA and to demonstrate whether there is an increase in the frequency of those markers of CD in patients with psoriasis.

Methods

Serum antigliadin antibody IgG and IgA, antiendomysial antibody IgA and anti-transglutaminase antibody IgA were studied in 37 (19 males) patients with psoriasis and 50 (23 males) healthy controls. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and duodenal biopsies were performed in patients with at least one positive marker.

Results

Antigliadin IgA was statistically higher in the psoriasis group than in the controls (p<0.05). Serological markers were found positive in 6 patients with psoriasis and 1 person from the control group. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed in all these persons, with biopsies collected from the duodenum. The diagnosis of CD was reported in only one patient with psoriasis following the pathological examination of the biopsies. Whereas one person of the control group was found to be positive for antigliadin antibody IgA, pathological examination of the duodenal biopsies obtain from this patient were found to be normal.

Conclusion

Antigliadin IgA prominently increases in patients diagnosed with psoriasis. Patients with psoriasis should be investigated for latent CD and should be followed up.

Keywords: Antibodies, Celiac disease, Duodenum, Psoriasis

INTRODUCTION

Coeliac disease (CD) is known as a chronic immune-mediated gluten-dependent enteropathy and results from an inappropriate T-cell-mediated immune response against ingested gluten in genetically predisposed people1. This is a disease that affects approximately 1% of the population, with affected people showing various symptoms that range from latent disease to overt enteropathy. The histopathological characteristics of CD are villus atrophy and crypt hyperplasia2,3. CD is not limited to only the digestive tract; it is a multisystemic disorder associated with skin manifestations, iron deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, hypertransaminasemia, endocrine disorders, neurological disorders and cancer4. Antigliadin antibody (AGA), antiendomysium antibody (EMA) and tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibody are used-in screening tests and to measure disease activity in CD5-8.

Psoriasis is a dermatosis with an etiology that is not completely known, but immune mechanisms are accepted to play a role in its pathogenesis. It progresses and relapses and is characterized by scaling, erythema, and less commonly, postulation9,10. Immune mechanisms play an important role in the disease's pathogenesis. In particular, an overexpression of T helper cell type 1 (Th1) cytokines and a relative under-expression of Th2 cytokines have been found in psoriatic patients11,12. Recent data indicate that HLA-Cw*0602 may play an important pathogenetic role in the majority of psoriasis patients13. Recent studies show an association between CD and psoriasis14-16. At present the relationship between CD and psoriasis remains controversial since there are few and contrasting data on this topic, with some authors maintaining that the association between CD and psoriasis is coincidental17.

In this study, we aimed to study the serological markers that are described for CD in patients with psoriasis, and to define the possible relationship between psoriasis and coeliac disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty-seven patients (18 females, 19 males; mean age 41.95±13.52) diagnosed with psoriasis were referred to the gastroenterology polyclinic from the dermatology polyclinic. The skin lesions of the patients with psoriasis were assessed by the same dermatologist. The severity of the psoriasis was assessed by use of the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scoring system7,8. In these patients, mean PASI was 20.56±9.37 and mean duration of the disease was 124.86±102.44 months (range, 4~468 months). Patients in the psoriasis group who had another disease were excluded from the study.

Fifty age and gender matched healthy individuals who were living in the same locale as the psoriasis patients and who did not have psoriasis, coeliac disease, autoimmune disease, food intolerance or a history of malabsorption or any familial predisposition for these diseases were assigned as the control group. Both the patients in the study group and the control group received gluten-containing diet.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture, following an overnight fast. In the serum specimens collected from the psoriasis patients and controls, IgA AGA and IgG AGA and IgA anti-transglutaminase (TGA) enzyme-linked immunosorbence were studied with immunosorbent assay (ELISA). IgA antibodies to endomysium (EmA) was assayed using indirect immunofluorescence.

Upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy was performed in patients who had at least one positive serologic marker, and 4 biopsy specimens from the 2nd part of the duodenum were collected from the patient. These biopsy specimens were assessed according to Marsh's classification by the same pathologist who was unaware of the clinical and serologic markers of the patient. In the modified Marsh's classification, 0 is assessed as normal mucosal structure without significant lymphocyte infiltration; I as lymphocytic enteritis (more than 30 lymphocytes/100 epithelial cells); II as lymphocytic enteritis and crypt hyperplasia; IIIA as partial villous atrophy; IIIB as subtotal villous atrophy and IIIC as total atrophy. The presence of at last one positive serology test plus Marsh 3 in the duodenal pathology was considered as CD18.

The project was approved by the local Ethics Committee and all patients gave their informed consent.

Statistical analysis

When the outcomes were evaluated, Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS) 2007 and Power Analysis and Sample Size (PASS) 2008 Statistical Software (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Besides the descriptive methods (mean, standard deviation) used for the assessment of the study data, in comparison of the quantitative data, Student's t-test was used for the comparison of the parameters showing a normal distribution and the Mann Whitney U-test for the comparison of the parameters not showing a normal distribution between the groups. The chi-square test was used for the comparison of the qualitative data. Statistical significance was evaluated as the level of p<0.05.

RESULTS

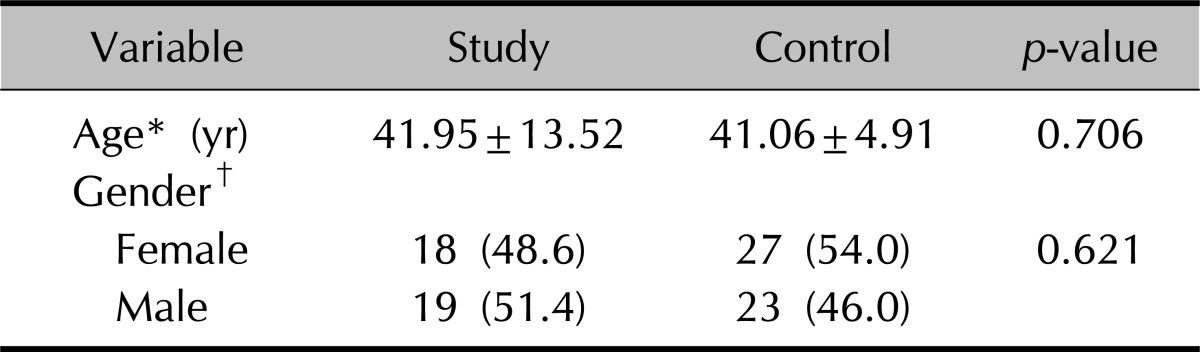

The study group constituted 37 patients (19 males and 18 females) diagnosed with psoriasis. Mean age was 41.95±13.52 years in the study group, age range was 17~65 years, mean duration of the disease was 124.86±102.44 months (range, 4~468 months) and mean PASI was 20.56±9.37. The control group consisted of 50 healthy individuals (23 males and 27 females) with a mean age of 41.06±4.91 years. There was no statistically significant difference between the study group and controls in terms of age and gender (p>0.05). Distribution of age and gender of the study and control groups is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of the groups

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). *Student's t-test, †chi-square test.

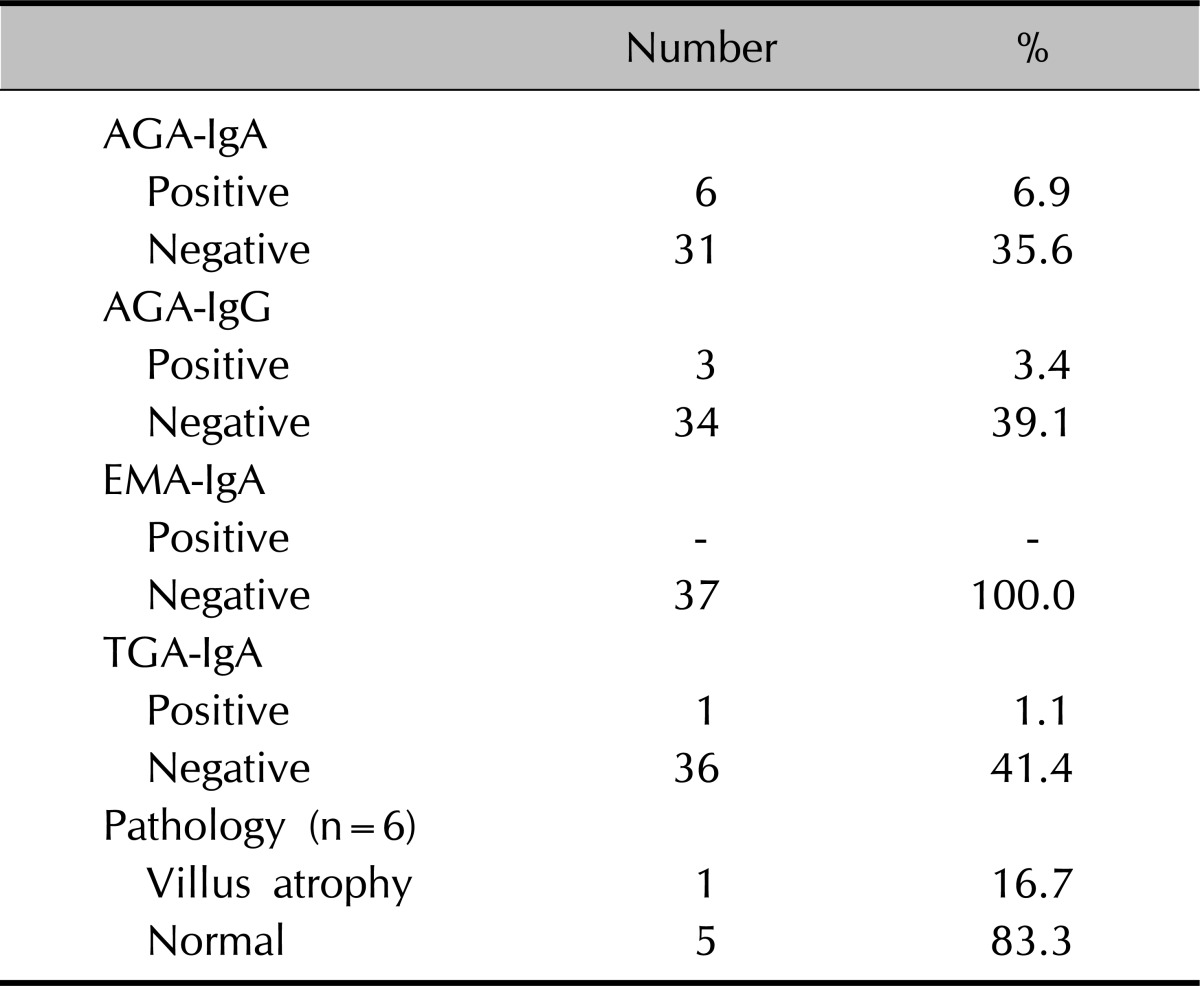

AGA IgA, IgG, EMA IgA, tGA IgA, which are known as CD-associated antibodies, were studied in both groups and when the outcomes were assayed, CD-associated antibody was found positive in 6 (16.2%) of the 37 psoriasis patients. In contrast, this value was positive in only one person (2.0%) in the control group. Distribution of CD-associated antibody in the psoriasis group is presented in Table 2. AGA-IgA 6 and AGA-IgG were positive in 3 cases in the psoriasis group, while EMA-IgA was negative in all the patients and TGA-IgA was positive in only one patient in the psoriasis group. Upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy was performed on 6 cases in whom the CD-associated antibody was positive, and at least 4 biopsies were collected from the duodenum in each case. Following the pathological examination of the biopsies, villous atrophy was identified in only one of the 6 cases and the patient was diagnosed with coeliac diseases and a gluten free diet (GFD) was introduced. The patient's gastrointestinal system symptoms and skin lesions were followed-up over 8 months with the patient on GFD.

Table 2.

Distribution of CD-associated antibody in psoriatic patient group

CD: coeliac disease, AGA: antigliadin antibody, Ig: immunoglobulin, EMA: antiendomysium antibody, TGA: anti-transglutaminase.

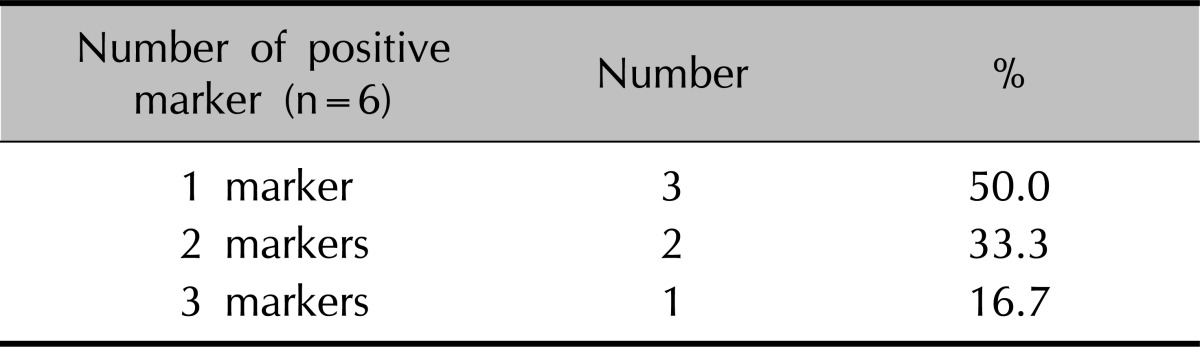

In the psoriasis group, 3 (16.7%) markers were positive in one case, 2 (33.3%) markers in two cases and 1 marker (50.0%) in three cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of positive markers in the study group

In the control group, AGA-IgA was found positive in only one (2.0%) person out of 50 healthy individuals. Upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy was performed on this person, and 4 biopsy specimens were collected from the duodenum. The case was reported as normal following the pathological examination of the biopsies.

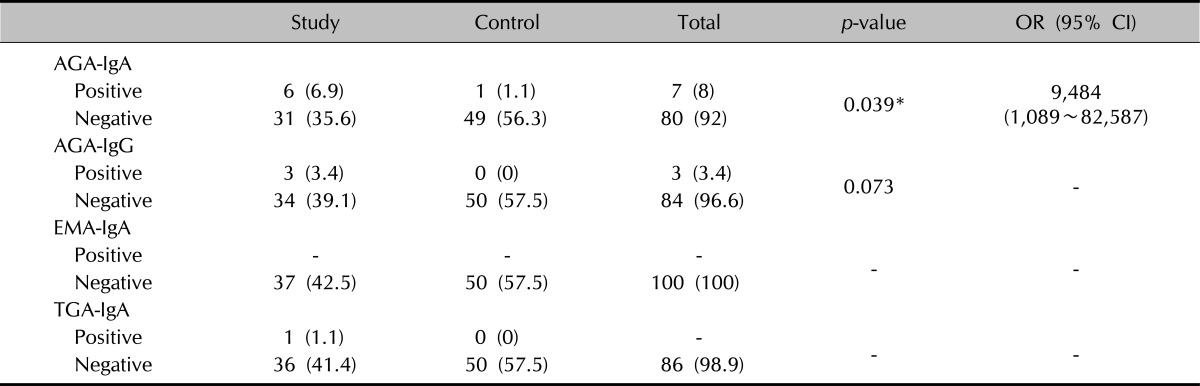

When the patient and control groups were analyzed in detail regarding the CD-associated antibodies, and the values compared, the incidence of AGA-IgA positivity in the psoriasis group was higher than in the controls and there was a statistically significant difference between the groups (p<0.05). Therefore, it was concluded that AGA-IgA positivity statistically increases the risk of CD 9,484 times in the psoriasis group (95% confidence interval [CI], 1,089~82,587) (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in AGA-IgG positivity (p>0.05). The positivities of EMA-IgA and TGA-IgA could not be evaluated due to the insufficient number of cases.

Table 4.

Evaluation of CD-associated antibodies regarding to the groups

Values are presented as number (%) or number (range). CD: coeliac disease, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, AGA: antigliadin antibody, Ig: immunoglobulin, EMA: antiendomysium antibody, TGA: anti-transglutaminase. Fisher's exact test was used. *p<0.05.

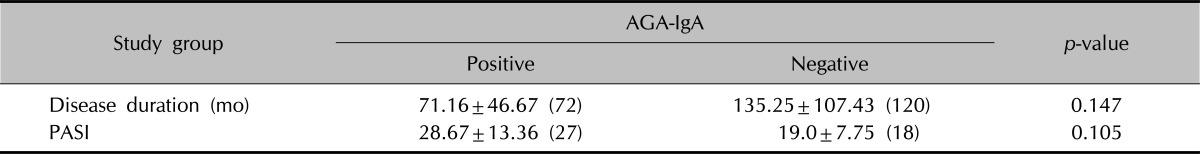

The duration of the disease was in the range of 4 to 468 months, and the mean duration was 124.86±102.44 months; PASI levels were in the range of 8 to 46, with a mean value of 20.56±9.37. When it was investigated to see whether there was a relationship between the duration of disease and CD-associated antibody positivity in the psoriasis group, there was no statistically significant difference found between duration of disease and AGA-IgA positivity (p>0.05). On analysis to see whether there was a statistical correlation between the psoriasis disease activity marker PASI and CD-associated antibody positivity in the psoriasis group, no statistically significant difference between AGA-IgA positivity and PASI levels was found (p>0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of AGA-IgA positivity and disease duration and PASI levels in the study group

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation (median). AGA: antigliadin antibody, Ig: immunoglobulin, PASI: psoriasis area and severity index. Mann-Whitney U-test was used.

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis characterized by scaling and erythema, and a course marked by relapses, and its etiology is not completely clear9. However, it is accepted as an immunologic disease, with immune mechanisms playing an important role in the pathogenesis11,12. CD is an autoimmune disease characterized clinically with malabsorption and histopathologically with villous atrophy, and it affects 1% of the general population. CD may be seen with other autoimmune diseases such as dermatitis herpetiformis, thyroiditis and diabetes mellitus; a higher incidence of CD is seen in patients who have concomitant autoimmune disease, particularly in persons who have familial autoimmune disease and in patients diagnosed with CD at a young age10,19,20.

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the possible relationship between psoriasis and CD, and to define the rate of CD in psoriasis patients compared to healthy individuals and to determine the incidence of serological markers known as CD indicators in these patients. Although IgA is a marker of coeliac disease, it may be seen in some other diseases such as IgA nephritis, sickle-cell anemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and hepatic disorders21.

When we studied these serologic markers of CD, we observed that the AGA-IgA was increased statistically significant (6.9%) in the psoriasis group compared to the controls (1.1%) (p<0.05). With AGA-IgG positivity, there was no statistically significant difference between the psoriasis group (3.0%) and the controls (p>0.05). When evaluating the EMA, there was no positive value in either group. When we looked at the TGA-IgA, there was only one positive case in the patient group, and it was completely negative in the control group. Therefore, we found statistically significant AGA-IgA positivity in the psoriasis group (p<0.05). We concluded that the presence of this increases the risk for CD in patients with psoriasis by 9,484 times compared to controls (95% CI, 1,089~82,587). When we analyzed the rate of positive serological markers, 50.0% of the patients had 3 positive serological markers, 33.3% had 2 positive serological markers and 16.7% had one positive marker.

In recent studies, the incidence of psoriasis in patients with CD has been reported to be increased, and genetic and common immune mechanisms and CD-associated enteropathy and/or intestinal barrier dysfunction occurring in undiagnosed or untreated CD patients may have a role in producing the skin lesions of psoriasis patients22-24. Furthermore, antibodies that are typical for CD such as antigliadin IgA, IgG, anti-endomysium IgA and anti-tTG IgA show an increase in psoriatic patients10,14-16,22,25-28. In a study by Woo et al.15, AGA-IgA was found to be 8.8%, IgG 3.8% and TGA 7.7% in psoriatic patients. Also, in another study by Ojetti et al.10 with 92 psoriatic patients, AGA-IgA was found to be 7.6%, EMA-IgA 4.34% and tGA-IgA 2.17%. They reported the incidence of CD in psoriatic patients as 4.34% following biopsies done on the patients, and that the CD incidence was prominently increased (p<0.0001) in psoriatic patients. In a recent study by Birkenfeld et al.22, the incidence of CD was increase in psoriatic patients compared to the control group (0.29% vs. 0.11%, p<0.001). It was reported that in the situation where CD was not diagnosed in psoriatic patients, latent CD may be present and this possibility should not be ignored in psoriatic patients.

In our study, gastrointestinal system endoscopy was performed on patients in whom CD-associated antibodies were found to be positive, and these patients comprised 6 from the psoriasis group and one healthy individual from the control group, and at least 4 biopsies were collected from the duodenum in each patient. Following pathologic examination of the biopsies, villous atrophy was reported in only one patient and in addition to the diagnosis of psoriasis, this case was diagnosed also with coeliac disease. On the follow-up of this patient who was placed on GFD, over 8 months, gastrointestinal symptoms regressed and the anemia improved, but the psoriasis-associated skin lesions persisted. In a previous case report, Addolorato et al.29 reported that the skin lesions in a 53 year old male patient with psoriasis improved in a short period of one month, and on the upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy carried out 3 months later, villous atrophy in the duodenal mucosa had regressed, and on examination of the repeat duodenal biopsy specimen, the duodenal mucosa had recovered. They stated that in this case with negative AGA and EMA, vitamin D deficiency was also in the foreground and that absorption improved with GFD and that the improvement in the skin lesions might have been due to correction of the vitamin D deficiency29.

However, GFD has a limited effect on psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and only a limited number of patients who have recovered with a GFD has been reported28-30. The mechanism of action of GFD is unclear in psoriatic patients who are AGA positive. Some researchers have hypothesized that the activation of T cells and the abnormal absorption of antigens due to the concurrent mucosal injury play an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriatic skin lesions29. There might be reactivity to some antigen that is present in both the intestinal mucosa and skin and that this antigen may be linked to gluten. A nonspecific effect may also be possible via cytokines induced in the gut26,31,32. When patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who recovered in a short time were examined, gastrointestinal symptoms were at a minimal level and all of these patients were AGA positive and EMA negative26,33,34. On the other hand, remission could be achieved by a long term GFD in those who were EMA positive, and had silent and classical CD26.

In some studies conducted, serologic markers that are positive in coeliac disease, especially AGA-IgA, haves been reported be possible markers of psoriasis disease activity15. In our study when we statistically analyzed whether there was a correlation between serologic markers that indicate the presence of CD and PASI, we could not find a relationship between PASI and antibody positivity in CD (p>0.05). Also in our study, there was no relationship between antibody positivity in CD and the duration of psoriasis (p>0.05).

Similar to our study, in their series of 130 psoriatic patients, Woo et al.15 also found a high rate of CD antibodies in these patients, while they also could not find a statistically significant correlation between this antibody positivity and psoriatic disease activity. However, in a study by Michaelsson et al.14 on the follow-up of patients with and without positive AGA over 3 months who had been put on GFD, it was reported that at the end of the 3rd month, the PSA index, a disease marker, declined with GFD in the group with positive CD antibodies, and that there was also a decrease in the AGA values, and that the same decrease in PASI of the groups who were negative for CD antibodies could not be observed at the end of the same period. Also, Lindqvist et al.27, demonstrated that the levels of CD-antibody were correlated with psoriasis disease markers, especially in patients with psoriatic arthritis. They reported that in the patients with high IgA-AGA, inflammation was in the foreground, and they suggested that sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein might increase with inflammation.

Contrary to the findings of all these studies, in a comparative study by Kia et al.35 of patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and a control group in 2007, no correlation between AGA positivity and psoriasis disease activity was found, as in our study, and and the AGA positivity was reported as 16%35.

In conclusion, CD-associated antibodies are markers of gluten sensitivity, and when these markers are positive, overt enteropathy may not be seen. However, if these patients are followed-up, they may later progress to gluten enteropathy. Finally, the AGA-IgA positivity rate was higher in psoriatic patients, and therefore these patients are always are at risk for latent and/or overt CD. AGA positivity is not associated with psoriasis disease activity and disease duration. Resolution of the skin lesions should not be expected in all cases and it should always be kept in mind that a patient subgroup that improves with GFD may exist. In conclusion, the incidence of CD in psoriasis patients may be much higher than in the normal population.

References

- 1.Dieterich W, Storch WB, Schuppan D. Serum antibodies in celiac disease. Clin Lab. 2000;46:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capristo E, Addolorato G, Mingrone G, De Gaetano A, Greco AV, Tataranni PA, et al. Changes in body composition, substrate oxidation, and resting metabolic rate in adult celiac disease patients after a 1-y gluten-free diet treatment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:76–81. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson JM, Robins G, Howdle PD. Advances in coeliac disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:129–134. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f3d95d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American gastroenterological association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dieterich W, Storch WB, Schuppan D. Serum antibodies in celiac disease. Clin Lab. 2000;46:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bürgin-Wolff A, Hadziselimovic F. Screening test for coeliac disease. Lancet. 1997;349:1843–1844. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Tibblin G, Lavö B. Endomysium antibodies are superior to gliadin antibodies in screening for coeliac disease in patients presenting supposed functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:105–110. doi: 10.1080/028134300750018990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sblattero D, Berti I, Trevisiol C, Marzari R, Tommasini A, Bradbury A, et al. Human recombinant tissue transglutaminase ELISA: an innovative diagnostic assay for celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1253–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby B, Griffiths CE. Novel immune-based therapies for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:546–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojetti V, Aguilar Sanchez J, Guerriero C, Fossati B, Capizzi R, De Simone C, et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in psoriasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2574–2575. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker BS, Swain AF, Griffiths CE, Leonard JN, Fry L, Valdimarsson H. Epidermal T lymphocytes and dendritic cells in chronic plaque psoriasis: the effects of PUVA treatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;61:526–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mailliard RB, Egawa S, Cai Q, Kalinska A, Bykovskaya SN, Lotze MT, et al. Complementary dendritic cell-activating function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells: helper role of CD8+ T cells in the development of T helper type 1 responses. J Exp Med. 2002;195:473–483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veal CD, Capon F, Allen MH, Heath EK, Evans JC, Jones A, et al. Family-based analysis using a dense single-nucleotide polymorphism-based map defines genetic variation at PSORS1, the major psoriasis-susceptibility locus. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:554–564. doi: 10.1086/342289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaëlsson G, Gerdén B, Hagforsen E, Nilsson B, Pihl-Lundin I, Kraaz W, et al. Psoriasis patients with antibodies to gliadin can be improved by a gluten-free diet. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:44–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo WK, McMillan SA, Watson RG, McCluggage WG, Sloan JM, McMillan JC. Coeliac disease-associated antibodies correlate with psoriasis activity. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:891–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardinali C, Degl'innocenti D, Caproni M, Fabbri P. Is the search for serum antibodies to gliadin, endomysium and tissue transglutaminase meaningful in psoriatic patients? Relationship between the pathogenesis of psoriasis and coeliac disease. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:187–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.47947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collin P, Reunala T. Recognition and management of the cutaneous manifestations of celiac disease: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:13–20. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;9:273–293. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1731–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Celiac disease beyond the gut. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:722–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamaeva OI, Reznikov IuP, Pimenova NS, Dobritsyna LV. Antigliadin antibodies in the absence of celiac disease. Klin Med (Mosk) 1998;76:33–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birkenfeld S, Dreiher J, Weitzman D, Cohen AD. Coeliac disease associated with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1331–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ventura A, Magazzù G, Greco L SIGEP Study Group for Autoimmune Disorders in Celiac Disease. Duration of exposure to gluten and risk for autoimmune disorders in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:297–303. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendel L, Hendel J, Johnsen A, Gudmand-Høyer E. Intestinal function and methotrexate absorption in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1982;7:491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1982.tb02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damasiewicz-Bodzek A, Wielkoszyński T. Serologic markers of celiac disease in psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michaëlsson G, Gerdén B, Ottosson M, Parra A, Sjöberg O, Hjelmquist G, et al. Patients with psoriasis often have increased serum levels of IgA antibodies to gliadin. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:667–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindqvist U, Rudsander A, Boström A, Nilsson B, Michaölsson G. IgA antibodies to gliadin and coeliac disease in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:31–37. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abenavoli L, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Vonghia L, Gasbarrini G, Addolorato G. Association between psoriasis and coeliac disease. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1393–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addolorato G, Parente A, de Lorenzi G, Dangelo Di, Abenavoli L, Leggio L, et al. Rapid regression of psoriasis in a coeliac patient after gluten-free diet. A case report and review of the literature. Digestion. 2003;68:9–12. doi: 10.1159/000073220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard MR, Turnbull AJ, Morley P, Hollier P, Webb R, Clarke A. A prospective study of the prevalence of undiagnosed coeliac disease in laboratory defined iron and folate deficiency. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:754–757. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.10.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajaj-Elliott M, Poulsom R, Pender SL, Wathen NC, MacDonald TT. Interactions between stromal cell--derived keratinocyte growth factor and epithelial transforming growth factor in immune-mediated crypt cell hyperplasia. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1473–1480. doi: 10.1172/JCI2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michaëlsson G, Kraaz W, Hagforsen E, Pihl-Lundin I, Lööf L, Scheynius A. The skin and the gut in psoriasis: the number of mast cells and CD3+ lymphocytes is increased in noninvolved skin and correlated to the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes and mast cells in the duodenum. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:343–346. doi: 10.2340/0001555577343346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazex A, Gaillet L, Bazex J. Gluten-free diet and psoriasis. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris) 1976;103:648–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cottafava F, Cosso D. Psoriatic arthritis and celiac disease in childhood. A case report. Pediatr Med Chir. 1991;13:431–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kia KF, Nair RP, Ike RW, Hiremagalore R, Elder JT, Ellis CN. Prevalence of antigliadin antibodies in patients with psoriasis is not elevated compared with controls. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:301–305. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200708050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]