Levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and the hepatic enzyme ALT are used to monitor medication toxicity [1]. ALP is important in osteoarticular processes because, excluding the liver, the highest concentrations of this enzyme can be found in the bone [1, 2]. High doses of clindamycin and first-generation cephalosporins have cytotoxic effects against osteoblasts in vitro [3-5]. The serum concentration of bone-specific ALP reflects the cellular activity of osteoblasts, and ALP elevation is encountered during bone formation or increased bone turnover [2, 6]. Furthermore, high ALP concentrations are found under septic conditions [2, 6-8]. ALP values are age and gender specific and vary throughout infancy and puberty [6].

In our prospective trial in Finland during 1983-2005, we treated 265 patients (age range, 3 months to 15 years) who had acute bone and/or joint infection by using antibiotics at exceptionally high doses and sequentially measured ALP and ALT levels [3, 9-11]. Data collection has been described in previous reports [9-11]. Briefly, the participants were randomized to receive short-term (20 days for osteomyelitis and 10 for septic arthritis) or long-term (30 days, regardless of manifestations) treatment with high-dose clindamycin (40 mg/kg/day divided into 4 equal doses, quater in die [four times a day, qid]) or a first-generation cephalosporin (150 mg/kg/day qid). The latter division was quasi-randomized. Intravenous administration lasted 2-4 days, and the course was completed orally with the same dosage. Children younger than 5 yr received adjuvant ampicillin or amoxicillin therapy (200 mg/kg/day qid) until Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection was ruled out [9]. Antibiotic-loaded cement and beads were not used. Staphylococcal infections were similarly treated, even if bacteremia was detected [12]. Only culture-positive cases were included in the main study. Children with known kidney or liver disease or with another underlying illness were excluded. Adjuvant dexamethasone therapy was not used, whereas non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were given routinely [13]. Total ALP, ALT, and creatinine levels were measured sequentially from blood samples taken on days 1, 2, 10, 19, and 29. Measurements have been reported as the serum concentration in IU/L. Bone alkaline phosphatase (BAP) isoenzyme or the liver ALP isoenzyme were not independently separated and quantified. The age- and sex-specific reference values reported by Turan et al. [6] were used for ALP. For ALT levels of children younger than 18 months, our cut-off values were 60 and 55 U/L for boys and girls, respectively. For older children, the values were 40 and 35 U/L for boys and girls, respectively [14]. Statview (version 5.0.1, Abacus Corporation, Baltimore, MD, USA) was used for data analysis. A t-test was used to compute P values. Confidence intervals were calculated with the Newcombe method [15].

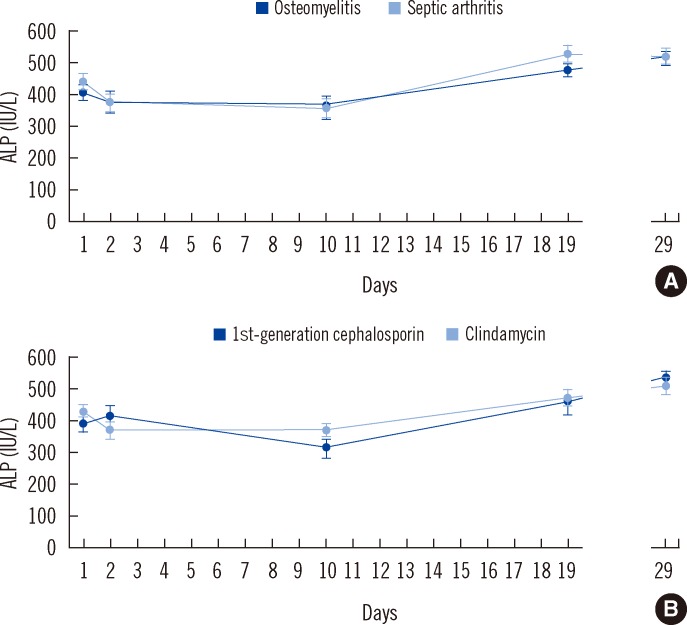

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common causative organism (75%, 199/265), followed by Hib (10%, 26/265), Streptococcus pyogenes (9%, 25/265), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (5%, 12/265). The median age was 8 yr (interquartile range, 4-11 yr). No child developed septic shock. The ALP levels on days 1, 2, 10, 19, and 29 were 415±13, 368±14, 344±18, 487±18, and 510±17 IU/L (mean±standard error of mean [SEM]), respectively. ALP levels for osteomyelitis (N=106) and septic arthritis (N=134) did not differ significantly (P=0.15, 0.95, 0.86, 0.66, and 0.73 on days 1, 2, 10, 19, and 29 respectively; Fig. 1). In osteomyelitis combined with septic arthritis (N=25), the ALP level was 346±34 and 422±44 IU/L on days 1 and 29, respectively. High ALP levels, exceeding 750 IU/L (range, 758-939 IU/L), on admission, were noted in 3 patients. ALP concentrations did not differ between clindamycin (N=99) and cephalosporin (N=70) recipients (P=0.18, 0.25, 0.09, 0.81, and 0.61 on days 1, 2, 10, 19, and 29, respectively). Data were similar for Hib patients treated with ampicillin or amoxicillin on days 1, 2, 10, and 29. However, on day 19, ALP levels were significantly higher among Hib patients; the mean±SEM value was 620±52 IU/L compared to those with Staphylococcus aureus (483±21 IU/L) or Streptococcus pyogenes (387±17 IU/L) disease (P=0.84, 0.68, 0.61, <0.05, and 0.87 on days 1, 2, 10,19, and 29, respectively). The mean serum creatinine levels were 55±1, 51±2, 53±1, 52±1, and 54±1 µmol/L (range, 17-88, 24-94, 28-103, 23-87, and 17-91 µmol/L, respectively) on days 1, 2, 10, 19, and 29, respectively. No cases of kidney failure were observed. Two clindamycin recipients developed a rash.

Fig. 1.

(A) Alkaline phosphatase levels in patients with osteomyelitis (N=106) versus patients with septic arthritis (N=134). (B) Alkaline phosphatase levels in patients given clindamycin (N=99) versus first-generation cephalosporin (N=70).

Abbreviation: ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Sequential ALP monitoring was continued for a month after starting therapy (Fig. 1). ALP levels were significantly higher on day 29 than on day 1 (P<0.0001). The same trend was seen in culture-negative drop-outs from the main study (N=80) (i.e., ALP levels increased from day 1 to 29 [P<0.0001]). In the short-term treatment groups, minor ALP elevation continued, even after antibiotic administration was stopped (i.e., osteomyelitis, 465±28 IU/L on day 19 to 483±36 IU/L on day 29; septic arthritis, 463±30 IU/L on day 10 to 545±38 IU/L on day 19). ALP levels did not differ on day 29 between the short- and long-term treatment groups (P=0.57 and P=0.85 in osteomyelitis and septic arthritis, respectively). Elevation beyond 500, 750, and 1,000 IU/L was observed in 82 (31%), 15 (6%), and 3 (1%) patients, respectively. No serious complications developed in this group, but 2 asymptomatic patients with past osteomyelitis showed lytic changes on plain radiography. Antibiotic administration was changed in 2 cases. ALT levels increased beyond the cut-off value in 6 patients but normalized during the follow-up in all patients, and no patients developed liver or kidney failure.

In the previous report, we demonstrated that bacteremia did not affect ALP concentrations on admission [11]. After the decrease seen during the first few days, a constantly increasing ALP curve was seen in the following few weeks, regardless of diagnosis, antibiotic administration, and duration of antibiotic administration. We suspect that ALP elevation may be part of the natural healing process in bone and joint infections. In a recent in vitro study, clindamycin stimulated cell metabolism of human osteoblasts at low concentrations and had cytotoxic effects at higher levels (i.e., 500 µg/mL) [4]. A first-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin) has been found to decrease osteoblast replication at 200 µg/mL and cause cell death at concentrations exceeding 10,000 µg/mL [5]. The in vivo concentrations are remarkably reduced; for instance, the cefazolin concentration normally seen in patients who have osteomyelitis and are receiving intravenous cefazolin is 5-13 µg/mL in pus and 3-5 µg/g in bone [16]. In septic arthritis, the peak concentration is seen 2 hr after antibiotic administration. For cephalexin, concentrations of 17 µg/mL in serum and 11 µg/mL in joint fluid have been reported [17]. In the current study, the increase in the ALP concentration was not linked to specific complications (e.g., clinical sequelae or worsening liver/kidney function). Major elevation occurred in 1% of the patients. The antibiotic treatment was changed in only 2 cases of extreme ALP elevation. Administering exceptionally large doses of reliable time-honored antibiotics proved to be a safe and effective strategy in these potentially severe infections. Liver- or kidney-related complications were not encountered, even when the ALP level increased greatly. Bone formation is initiated by osteoblasts, and this activity is reflected in the serum concentration of BAP. In the current series, there were no significant differences in the ALP levels in patients with bone involvement, probably because BAP represents less than one-fourth of the total ALP concentration [18, 19]. Furthermore, bone remodeling in osteomyelitis mainly occurs after the acute phase, when the intense inflammatory process has passed. ALP activity changes with age, and this also affects reference values [6]. A clear limitation of the study was that BAP was not analyzed separately from total ALP (nor was liver ALP separated). Abnormal levels of ALP isoenzymes may be found, even if the total ALP level remains normal [20]. No patient went into septic shock, which might have caused high ALP concentrations. Our patients originated from a high-income country and had no history of underlying illnesses, immunodeficiency, or undernourishment. Furthermore, no cases of infection with Kingella kingae, Salmonella spp., or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains were detected. All these factors could have influenced ALP measurements in combination. Furthermore, no control population was available, other than the reference values available for healthy children [6].

The patients were enrolled prospectively, and no equally large dataset is available yet for pediatric bone and joint infections. Our results show that, despite the exceptionally high doses of antibiotics used in this study, major elevations in ALP are rare and have no detectable correlation with adverse events. Minor ALP elevation is common in bone and joint infections and does not necessitate treatment alteration.

Acknowledgements

Markus Pääkkönen has received grants from the Foundation of Pediatric Research, Finland, and the Foundation for Education and Research of the Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Warnes TW. Alkaline phosphatase. Gut. 1972;13:926–937. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.11.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corathers SD. Focus on diagnosis: the alkaline phosphatase level: nuances of a familiar test. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:382–384. doi: 10.1542/pir.27-10-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peltola H, Pääkkönen M, Kallio P, Kallio MJ OM-SA Study Group. Clindamycin vs. first-generation cephalosporins for acute osteoarticular infections of childhood --a prospective quasi-randomized controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:582–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naal FD, Salzmann GM, von Knoch F, Tuebel J, Diehl P, Gradinger R, et al. The effects of clindamycin on human osteoblasts in vitro. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0561-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edin ML, Miclau T, Lester GE, Lindsey RW, Dahners LE. Effect of cefazolin and vancomycin on osteoblasts in vitro. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;333:245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turan S, Topcu B, Gökçe I, Güran T, Atay Z, Omar A, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels in healthy children and evaluation of alkaline phosphatase z-scores in different types of rickets. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3:7–11. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.v3i1.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tung CB, Tung CF, Yang DY, Hu WH, Hung DZ, Peng YC, et al. Extremely high levels of alkaline phosphatase in adult patients as a manifestation of bacteremia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1347–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quale JM, Mandel LJ, Bergasa NV, Straus EW. Clinical significance and pathogenesis of hyperbilirubinemia associated with Staphylococcus aureus septicemia. Am J Med. 1988;85:615–618. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peltola H, Pääkkönen M, Kallio P, Kallio MJ Osteomyelitis-Septic Artghritis (OM-SA) Study Group. Prospective, randomized trial of 10 days versus 30 days of antimicrobial treatment, including a short-term course of parenteral therapy, for childhood septic arthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1201–1210. doi: 10.1086/597582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peltola H, Pääkkönen M, Kallio P, Kallio MJ Osteomyelitis-Septic Arthritis Study Group. Short- versus long-term antimicrobial treatment for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of childhood: prospective, randomized trial on 131 culture-positive cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1123–1128. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f55a89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pääkkönen M, Kallio MJ, Kallio PE, Peltola H. C-reactive protein versus Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count and alkaline phosphatase in diagnosing bacteraemia in bone and joint infections. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:E189–E192. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pääkkönen M, Kallio PE, Kallio MJ, Peltola H. Management of osteoarticular infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus is similar to that of other etiologies: analysis of 199 staphylococcal bone and joint infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:436–438. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31824657dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harel L, Prais D, Bar-On E, Livni G, Hoffer V, Uziel Y, et al. Dexamethasone therapy for septic arthritis in children: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:211–215. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182092869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.England K, Thorne C, Pembrey L, Tovo PA, Newell ML. Age- and sex-related reference ranges of alanine aminotransferase levels in children: European paediatric HCV network. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:71–77. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818fc63b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetzlaff TR, Howard JB, McCraken GH, Caldereon E, Larrondo J. Antibiotic concentrations in pus and bone of children with osteomyelitis. J Pediatr. 1978;92:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson JD, Howard JB, Shelton S. Oral antibiotic therapy for skeletal infections of children. I. Antibiotic concentrations in suppurative synovial fluid. J Pediatr. 1978;92:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang L, Grey V. Pediatric reference intervals for bone markers. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Eapen E, Steele S, Grey V. Establishment of reference intervals for bone markers in children and adolescents. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Hoof VO, De Broe ME. Interpretation and clinical significance of alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme patterns. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1994;31:197–293. doi: 10.3109/10408369409084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]