Abstract

The misfolding and aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides into amyloid fibrils is regarded as one of the causative events in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Tanshinones extracted from Chinese herb Danshen (Salvia Miltiorrhiza Bunge) were traditionally used as anti-inflammation and cerebrovascular drugs due to their antioxidation and antiacetylcholinesterase effects. A number of studies have suggested that tanshinones could protect neuronal cells. In this work, we examine the inhibitory activity of tanshinone I (TS1) and tanshinone IIA (TS2), the two major components in the Danshen herb, on the aggregation and toxicity of Aβ1–42 using atomic force microscopy (AFM), thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence assay, cell viability assay, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. AFM and ThT results show that both TS1 and TS2 exhibit different inhibitory abilities to prevent unseeded amyloid fibril formation and to disaggregate preformed amyloid fibrils, in which TS1 shows better inhibitory potency than TS2. Live/dead assay further confirms that introduction of a very small amount of tanshinones enables protection of cultured SH-SY5Y cells against Aβ-induced cell toxicity. Comparative MD simulation results reveal a general tanshinone binding mode to prevent Aβ peptide association, showing that both TS1 and TS2 preferentially bind to a hydrophobic β-sheet groove formed by the C-terminal residues of I31-M35 and M35-V39 and several aromatic residues. Meanwhile, the differences in binding distribution, residues, sites, population, and affinity between TS1-Aβ and TS2-Aβ systems also interpret different inhibitory effects on Aβ aggregation as observed by in vitro experiments. More importantly, due to nonspecific binding mode of tanshinones, it is expected that tanshinones would have a general inhibitory efficacy of a wide range of amyloid peptides. These findings suggest that tanshinones, particularly TS1 compound, offer promising lead compounds with dual protective role in anti-inflammation and antiaggregation for further development of Aβ inhibitors to prevent and disaggregate amyloid formation.

Keywords: Aβ, amyloid, tanshinone, Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, age-related neurodegenerative disorder, which has affected over 26 million people worldwide. This number is predicted to increase to 106 million by 2050.1 The pathological hallmarks in AD are characterized by the coexistence of the extracellular senile plaques of amyloid-β (Aβ) and the intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein in the brain of AD patients. The formation of senile plaques is a multiple and complex self-assembly process of Aβ peptides, involving (i) in vivo production of Aβ peptides by proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase at Asp672 and by γ-secretase at Ala7132 and (ii) abnormal aggregation of Aβ peptides from their soluble unstructured monomers to β-sheet-rich oligomers to protofibrils to insoluble amyloid fibrils.3−5

In principle, any step along the process of Aβ production, aggregation, and clearance can be considered as a potential therapeutic target to treat AD. The common inhibition strategies include interference with (1) the expression of the APP, (2) the proteolytic cleavage of APP into Aβ peptides, (3) the clearance of Aβ peptides from the system, and (4) the aggregation of Aβ into soluble oligomers and insoluble amyloid fibrils. Although significant efforts and progress have been made to block the expression, cleavage, or clearance of Aβ peptides in these upstream processes,6−8 these strategies have not produced any effective pharmaceutical agents to date. On the other hand, since neurotoxicity is mainly associated with the formation of Aβ aggregates with β-sheet-rich structure, the search for antiaggregation compounds and β-sheet-disrupting compounds provides an alternative therapeutic approach to reduce, inhibit, and even reverse Aβ aggregation.9,10 More importantly, since the misfolding and self-aggregation of amyloid peptides into β-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils is a general and characteristic process for all amyloid peptides, antiaggregation and anti-β-sheet inhibitors against Aβ aggregation could potentially have a general inhibitory ability for other amyloid peptides.

Since no cure has been found to treat AD to date, extensive efforts have been made to develop a broad range of Aβ inhibitors including peptides and peptide mimetics,11−15 polymers,16,17 nanoparticles,18,19 and small organic compounds20,21 to prevent amyloid formation. Particular attention has been paid to small chemical compounds derived from natural products, due to the ease of accessibility and structural modification and a broad inhibitory activity. For instance, theaflavins from black tea,22 EGCG from green tea,23 and coffee compounds24 have been reported to inhibit in vitro amyloid formation of a range of amyloid peptides of Aβ, IAPP, and α-synuclein, as well as to reduce cell toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Although the exact mechanisms of amyloid inhibitors still remain unclear, intermolecular interactions between amyloid peptides and inhibitors are thought to induce disruptive structural perturbation and association of amyloid peptides during amyloid formation process. Such inhibitor–amyloid interactions could result in different, but not mutually exclusive inhibition mechanisms, including (i) retaining native or non-β-structure conformation of amyloid peptides, (ii) trapping the most toxic amyloid oligomers and stabilize nontoxic amyloid aggregates, (iii) redirecting aggregation pathways toward off-pathway nontoxic oligomers, (iv) altering aggregation kinetics to bypass transit oligomer states by slowing down more-toxic oligomer formation or accelerating less-toxic fibril formation, and (v) arresting the disruptive interactions of inhibitor-peptide complex with cell membrane.25 Despite the promising inhibitory activity of all Aβ inhibitors as reported above, none of them has been used for the clinical treatment of AD.

For clinical applications, Aβ inhibitors must resist premature enzymatic degradation, target specific tissues, cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and facilitate nucleus uptake, while not inducing inflammation, toxicity, and other adverse immune responses. Additionally, it is well-known that the cerebral vessels, especially capillary blood vessels, are the common places to clear Aβ by transporting Aβ from brain tissue to circulation system. Accumulation of Aβ on the inner wall of capillary blood vessels has been shown to cause vessel damage,26,27 resulting in the failure of Aβ clearance, which in turn promotes neuroinflammation and dementia in AD.28 Thus, search for Aβ inhibitors with a vessel protective ability, despite being often neglected, could lead to a promising therapy for AD treatment. Such inhibitors not only prevent Aβ aggregation in the extracellular fluid and around the cerebral vessels, but also protect vessels from Aβ-induced damage.

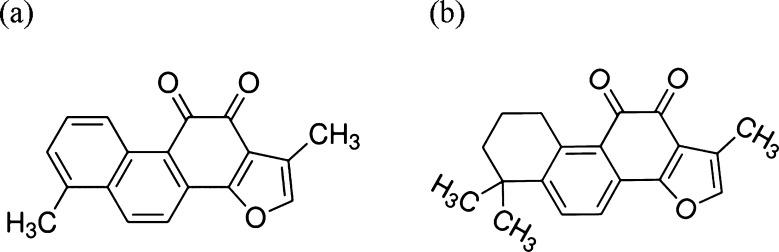

Here, we for the first time report the discovery of novel tanshinone compounds that possess antiaggregation ability to Aβ1–42 peptide. Tanshinones are lipophilic compounds extracted from the roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (SMB) (SMB is also named as a traditional Chinese herbal medicine of “Danshen”). Tanshinone I (TS1) and tanshinone IIA (TS2) are the two most abundant components in the SMB herb (Figure 1). Due to the well-known antioxidation effect29 and acetylcholinesterase inhibition effect,30 tanshinones have been widely used for treating cardiovascular disease in China since the 1970s.31−35 As the commercialized drugs to treat cardiovascular diseases, tanshinones readily cross the BBB. More importantly, a number of studies have also shown that tanshinones display a promising protective effect on neuron cells.36−38 The dual protective roles of tanshinones in neuronal cells and blood vessels may also provide the inhibitory effect on Aβ aggregation and cytotoxicity. In this work, we have examined the inhibitory activity of TS1 and TS2 compounds on the aggregation and toxicity of Aβ1–42 using atomic force microscopy (AFM), thioflavin-T fluorescence (ThT), cell viability assay, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. Experimental results show that both TS1 and TS2 inhibit in vitro amyloid formation by Aβ, disaggregate preformed Aβ fibrils, and protect cells from Aβ-induced toxicity, but TS1 shows higher inhibitory potency than TS2. The tanshinone compounds are one of a very small set of molecules, which have been shown to disaggregate Aβ amyloid fibrils to date. MD simulations further reveal different binding information (binding sites, affinities, and populations) between TS1-Aβ and TS2-Aβ, which provides atomic insights into the underlying inhibition mechanisms. This work indicates that tanshinone and its derivatives could be very promising therapeutic inhibitors with both antiaggregation and antioxidant activities to protect neurons from Aβ damage.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (a) tanshinone I (TS1) and (b) tanshinone IIA (TS2).

Results and Discussion

Tanshinones Inhibit Amyloid Formation by Aβ in Vitro

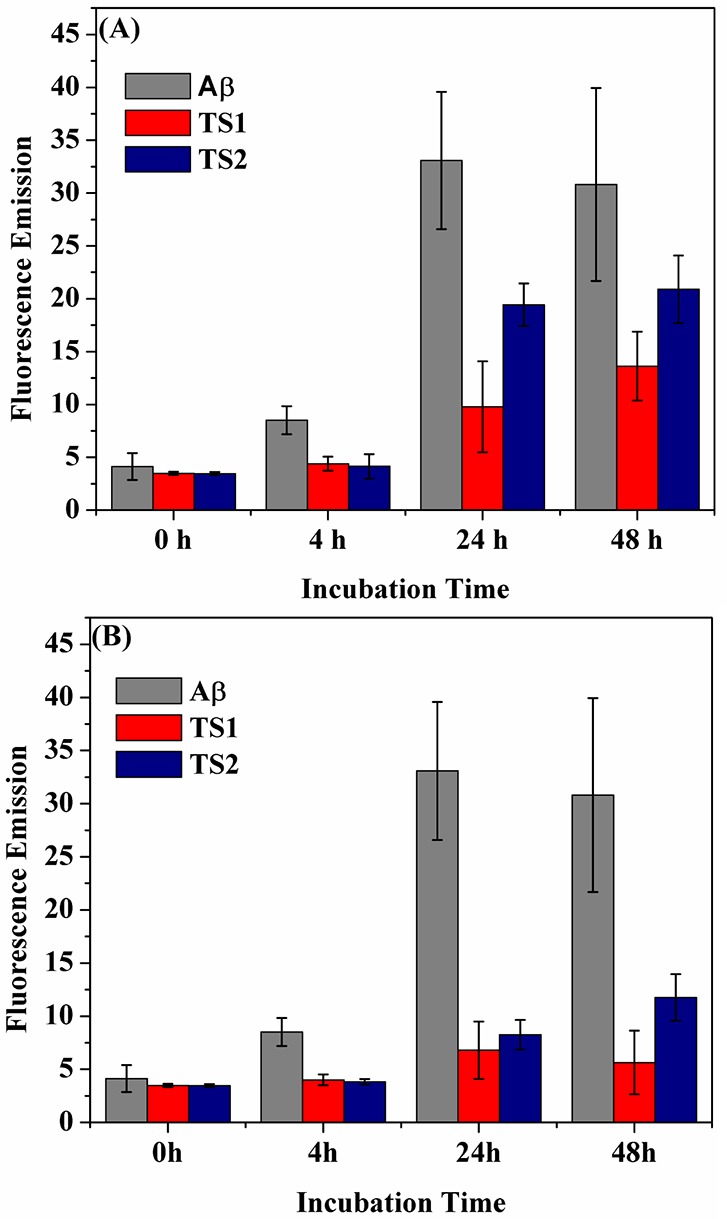

To examine the inhibitory effect of TS1 and TS2 on Aβ aggregation, the kinetics and morphological changes of Aβ1–42 amyloid formation in the presence of different molar ratios (Aβ:TS) of two tanshinone compounds were monitored by ThT fluorescence assay and AFM. An Aβ1–42 solution of 20 μM (with or without tanshinone) was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. ThT fluorescence assay has been widely used to detect the formation of amyloid fibrils because the binding of thioflavin dyes to amyloid fibrils enables reduction of self-quenching by restricting the rotation of the benzothiozole and benzaminic rings, leading to a significant increase in fluorescence quantum yield.39−41 For Aβ aggregation only, the ThT-binding assay (Figure 2) and the following AFM images (Figure 3) showed that, within 4 h, fluorescence signals slightly increased, accompanying with the formation of very few short and unbranched protofibrils of 7–8 nm in height (Figure 3A1). After 24 h reaction, a strong ThT emission was observed and remained almost unchanged within statistic errors between 24 and 48 h incubation. AFM images of pure Aβ samples without inhibitors revealed extensive long and branched fibrils with average height of 12–15 nm and average length of 1.5 μm (Figure 3A2).

Figure 2.

Time-dependent ThT fluorescence changes for Aβ1–42 incubated with tanshinones at the mole ratio of (A) Aβ:TS = 1:1 and (B) Aβ:TS = 1:2, as compared to Aβ alone. Error bars represent the average of three replicate experiments.

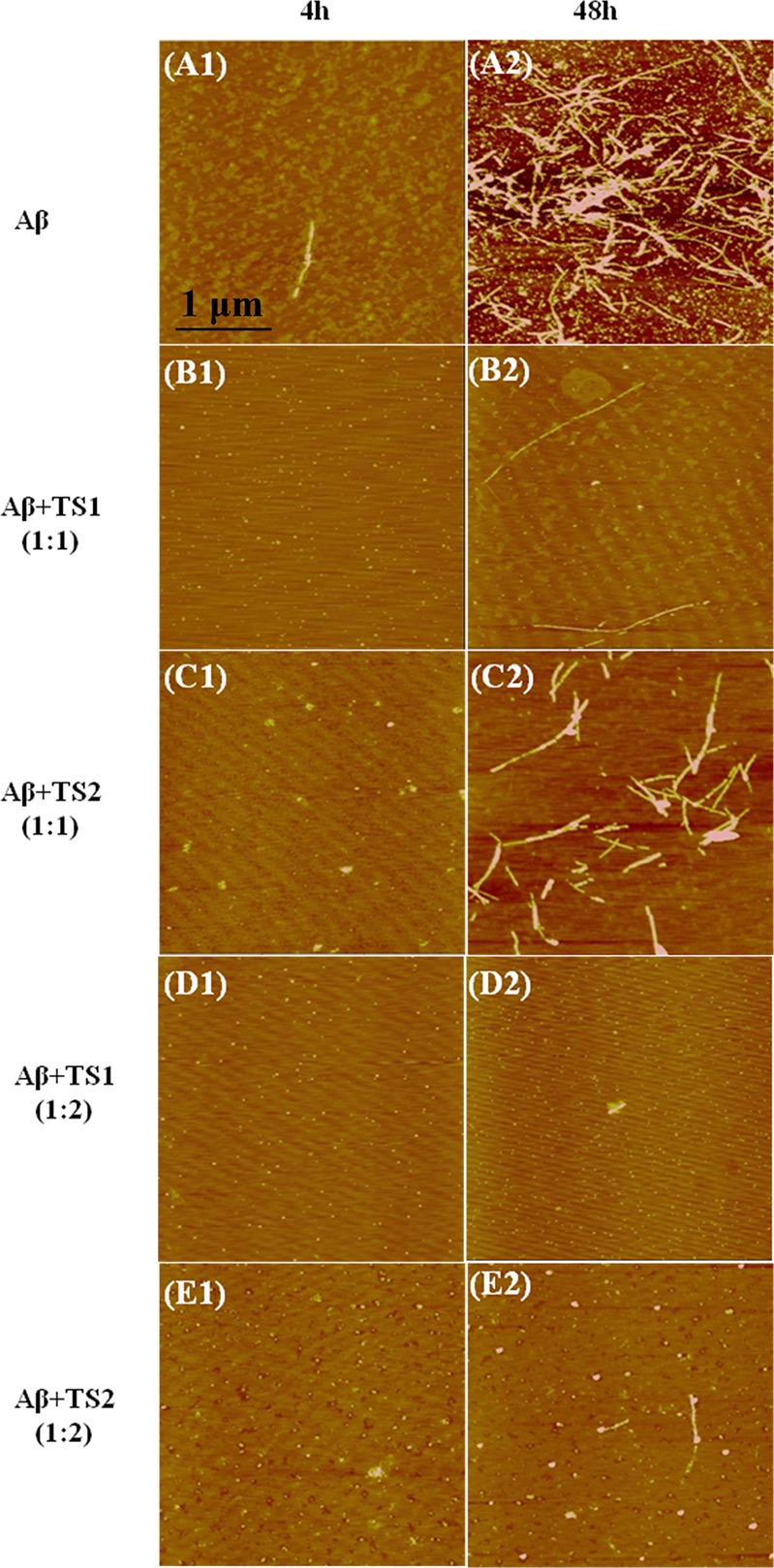

Figure 3.

AFM images of Aβ amyloids at 4 and 48 h (A) in bulk solution and when incubating with (B) TS1 at a molar ratio of Aβ:TS1 = 1:1, (C) TS2 at a molar ratio of Aβ:TS2 = 1:1, (D) TS1 at a molar ratio of Aβ:TS1 = 1:2, and (E) TS2 at a molar ratio of Aβ:TS2 = 1:2.

In the presence of equimolar ratios of tanshinone-derived compounds (i.e., Aβ:TS = 1:1), both TS1 and TS2 showed an increased lag time at the lag phase and a reduced maximum fluorescence intensity at the following growth phase. Specifically, within the first 4 h, no fluorescence change and no protofibrils were observed by ThT and AFM, respectively. AFM images showed some small spherical particles of 1–3 nm in the Aβ-TS1 samples (Figure 3B1) and of 1–6 nm in the Aβ-TS2 samples (Figure 3C1), suggesting that TS1 has stronger inhibitory potency than TS2 at the early lag phase. As reaction time increased, the ThT intensity relative to Aβ samples without inhibitors was decreased by 78.2% at 24 h and 65.8% at 48 h for TS1-Aβ systems, as well as by 44.8% at 24 h and 34.6% at 48 h for TS2-Aβ systems. To confirm the ThT results, the AFM images also revealed that TS1 generated very few and thin fiberlike materials (Figure 3B2), while TS2 produced more short thicker structures and some amorphous materials (Figure 3C2).

When the molar ratio of Aβ:TS increased to 1:2, the inhibition effect of both compounds became even more pronounced. The lag phase times were prolonged. The final ThT fluorescence intensity at 24 h was reduced by 88.5% for TS1 and by 83.4% for TS2, and no significant fluorescence change was observed between 24 and 48 h (Figure 2). Consistently, the AFM images showed that with TS1 treatment, neither amorphous aggregates nor detectable amyloid fibrils were observed upon 48 h incubation (Figure 3D1 and 3D2). For the Aβ-TS2 samples, unlike the formation of arrays of fibril-like materials at 1:1 molar ratio, the presence of TS2 with a higher concentration led to some small spherical species and few thin protofibrils (Figure 3E1 and E2). Taken together, ThT and AFM data clearly demonstrates that both TS1 and TS2 enable to inhibit amyloid formation by Aβ at the early lag phase and at the later growth phase, in which TS1 exhibits stronger inhibition effect on Aβ aggregation than TS2. This finding suggests that both compounds are able to bind to monomers, intermediates, and mature fibrils to interfere with structural conversion from random coils to β-structures or the association of additional monomers with the existing amyloid species to form large aggregates. Since TS1 and TS2 contain an aromatic ring structure similar to other typical organic Aβ inhibitors,42,43 it is likely that tanshinone interacts with aromatic residues of Aβ to form π–π stacking arrangement between tanshinone and Aβ. Moreover, the planar conformation of tanshinones also provides geometrical preference to align with the hydrophobic groove of amyloid fibrils, which possess an in-register organization of side chains in the regular cross-β-sheet structure. All of these effects could be attributed to the inhibition of Aβ aggregation.

Tanshinones Disassemble Aβ Fibrils in Vitro

The alternative potential therapeutic strategy to treat AD is to reduce the amount of the existing amyloid plaques.44,45 A very few molecules have been reported to disaggregate Aβ amyloid.46−48 During the inhibition experiments, we observed that the ThT fluorescence signal tended to fall after the addition of tanshinone at the later stages of the fibril formation, suggesting that tanshinone may also act to reverse the aggregation process and to disassemble preformed Aβ fibrils. To determine the ability of Aβ fibril dissolution by tanshinone in vitro, we set up experiments in which tanshinone was incubated with preformed fibrils. Aβ fibrils (20 μM) were first prepared by incubating Aβ monomers in solution for 48 h, which is sufficiently long enough for Aβ to grow into mature fibrils as evidenced by AFM images (Figure 3A2) and ThT fluorescence (Figure 2). Upon 48 h incubation, Aβ fibril solution was then coincubated with TS1 or TS2 with different molar ratios of Aβ:TS (1:1, 1:2, and 1:5) for another 48 h at 37 °C.

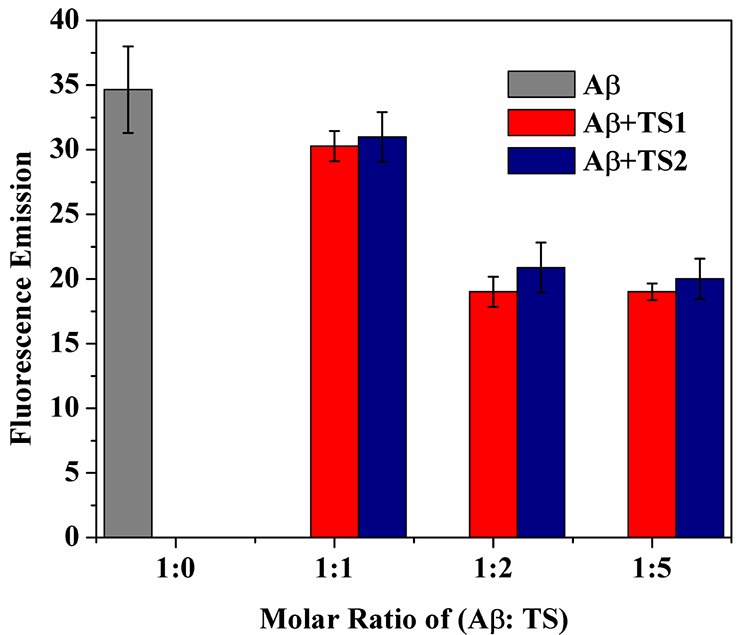

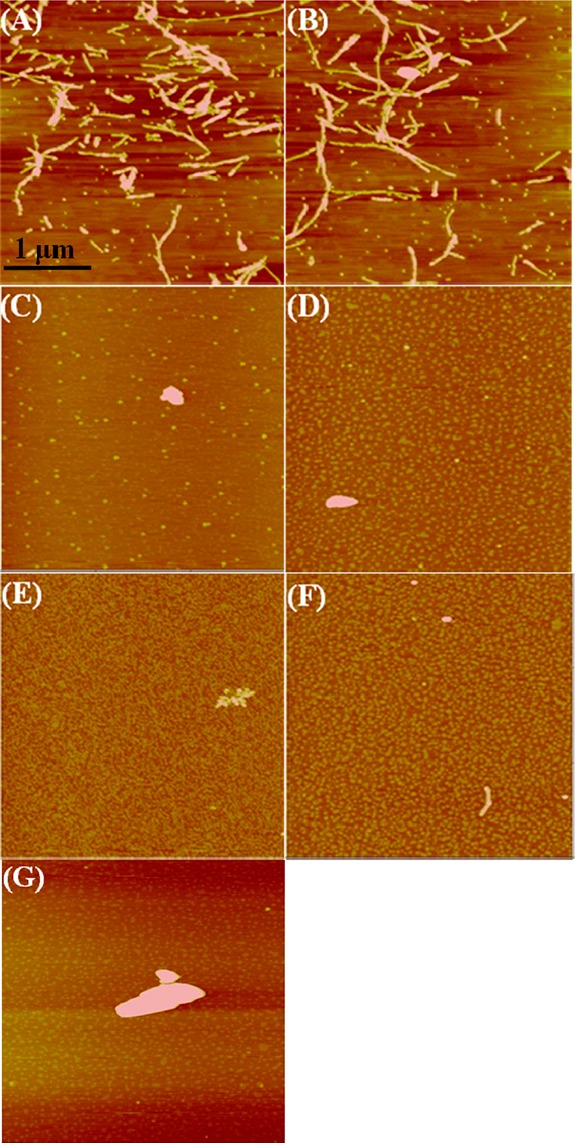

Figures 4 and 5 show a collection of fluorescence intensities and Aβ morphologies of the Aβ-tanshinone samples at the same time point of 48 h, respectively. At an equimolar ratio of Aβ-TS (1:1), TS1 or TS2 only induced a subtle decrease in fluorescence (∼0.8%) as compared to the untreated control of Aβ sample (Figure 4). The corresponding AFM images also confirmed the still existence of dense and branched fibrils (Figure 5A, B) with a similar morphology to control fibrils (Figure 3A2). This finding suggests that, at the equimolar ratio of TS:Aβ, the dissolution process is very slow and probably only a very small fraction of Aβ dissociates from the fibrils. In contrast, when Aβ fibrils were treated with a 1:2 molar ratio of Aβ:TS, the ThT intensity was decreased by ∼30% for both TS1 and TS2, indicating the loss of the preformed amyloid fibrils that may have converted to much shorter aggregates, which did not generate an observable ThT fluorescence. Further increase of TSs concentration to Aβ:TS = 1:5 showed almost no change in ThT intensity. Consistent with ThT results, AFM images also revealed similar Aβ morphologies upon the disaggregation of the preformed Aβ fibrils with 1:2 or 1:5 molar ratios. Most of the AFM chips were covered with different aggregates ranging from small spherical particles of 2–6 nm, amorphous aggregates of 3–15 nm, very few thin and short aggregates (Figure 5C–F), as well as a few large and irregular-shaped deposits (Figure 5G). The disaggregation results showed that TS1 and TS2 had comparable ability to disassemble the existing Aβ fibrils, although TS1 showed a better inhibitory potency to prevent Aβ aggregation than TS2. The sigmoidal-like dose-dependent disaggregation behavior also suggests that the dissolution of the fibrils will slow down until the formation of stable Aβ-TS complexes.

Figure 4.

Disaggregation effect of TS1 and TS2 on Aβ mature fibers at a molar ratio of Aβ:TS = 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5. Error bars represent the average of three replicate experiments.

Figure 5.

AFM images of preformed Aβ fibrils after incubation with the tanshinone compounds for 48 h at different conditions of (A) TS1 (Aβ:TS1 = 1:1), (B) TS2 (Aβ:TS2 = 1:1), (C) TS1 (Aβ:TS1 = 1:2), (D) TS2 (Aβ:TS2 = 1:2), (E) TS1 (Aβ:TS1 = 1:5), (F) TS2 (Aβ:TS2 = 1:5), and (G) TS2 (Aβ:TS2 = 1:2).

Tanshinones Protect Cultured Cells from Aβ-Induced Toxicity

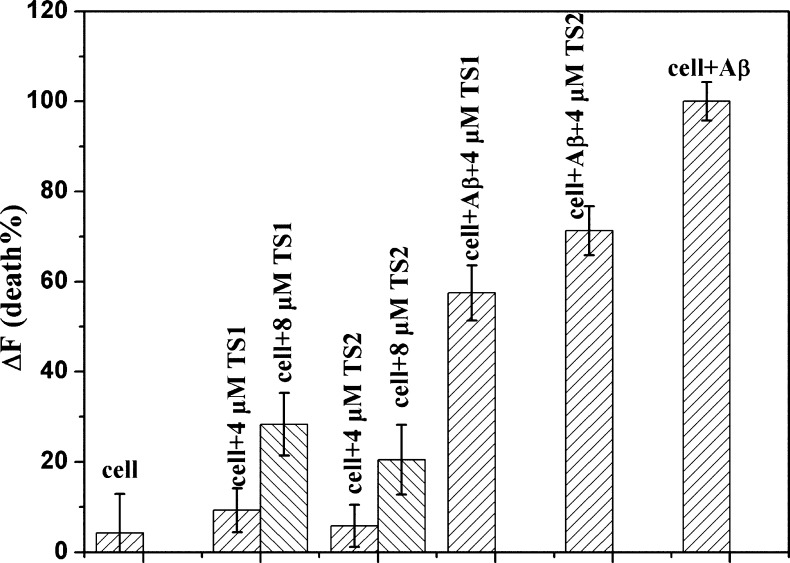

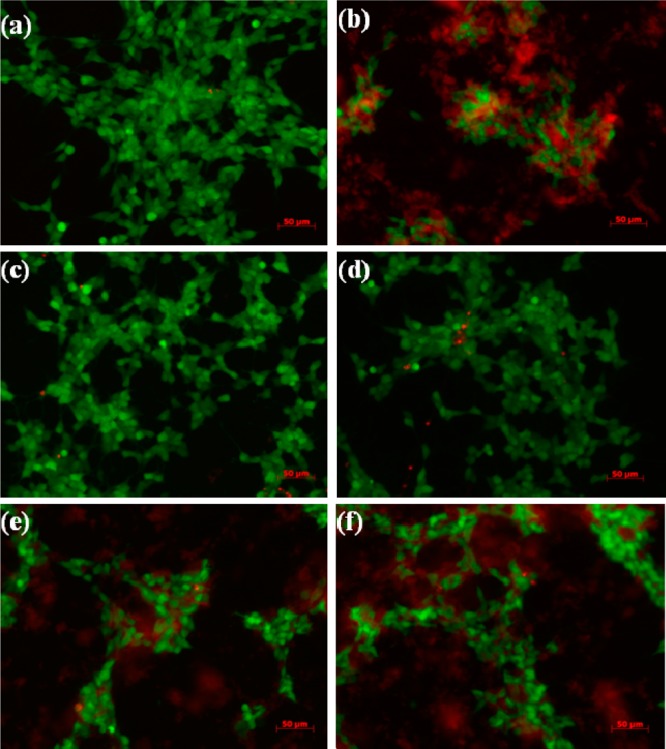

In order to determine whether tanshinone compounds are able to protect neuronal cells from toxic Aβ species, we conducted cell viability experiments to compare the toxic effects of Aβ, TS1, TS2, Aβ-TS1, and Aβ-TS2 on SH-SY5Y cells using the SH-SY5Y live/dead assay, which is widely used in studies of Aβ toxicity. Opti-MEM reduced serum medium was used to minimize the noise of fluorescence. We then set the cell death data obtained from Aβ-cell control experiment as a basis of 100% to normalize other data for comparison. As shown in Figure 6, incubation of SH-SY5Y cells with 20 μM Aβ for 24 h led to significant toxicity as expected; cell death was ∼95% higher than untreated cells. When treated the cells with 8 μM TS1 or TS2 alone (Aβ:TS = 1:0.4), cell death was 25.3% and 20.5% (Figure 6), respectively. Considering the physiological concentration of Aβ is as low as 10–9 M,49 8 μM tanshinone may exceed a lethal dose to induce cell death. We thus reduced the concentation of TS1 or TS2 to a clinical trial level of 4 μM for cell viability tests. As expected, the use of 4 μM TS1 or TS2 alone only induced 9.3% and 5.8% cell death, comparable to native cell apotosis of 4.3%. We then performed Aβ-tanshione cell toxicity experiments using a 1:0.2 mixture of Aβ (20 μM) and tanshinones (4 μM). It can be seen that the presence of a small amount of tanshinones greatly decreased the percentage of dead cells to ∼57.5% for TS1 and ∼71.3% for TS2 (Figure 6). TS1 appears to be less toxic than TS2 by 13.8%. Consistently, fluorescence microscopy showed that when treating SH-SY5Y cells with pure TS1 or pure TS2, no observable signs of cell death were observed (Figure 7c, d), indicating the nontoxic effect of tanshinone compounds on cells at a 4 μM level. However, SH-SY5Y cells treated with a 1:0.2 molar ratio of Aβ-TS1/TS2 showed a certain degree of cell death as indicated by cell shrinkage and cell detachment from the culture substratum (Figure 7e and f), but the quantity of dead cells was still much less than that of massive dead cells induced by Aβ only (Figure 7b). Cell-toxicity experiments demonstrate a significant level of tanshione-induced cell protection, indicating that tanshione is an effective inhibitor of Aβ-induced in vitro toxicity.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of Aβ-induced cytotoxicity against SH-SY5Y cells. Cell death was determined using live/dead assay and evaluated by fluorescence change (ΔF). Error bars represent the average of three replicate experiments.

Figure 7.

Representative fluorescence microscopy images of SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h incubation with (a) medium only, (b) Aβ, (c) 4 μM TS1, (d) 4 μM TS2, (e) 20 μM Aβ and 4 μM TS1, and (f) 20 μM Aβ and 4 μM TS2. Live cells were stained by green, while dead cells were stained by red.

Molecular Insights into Binding Mode of Tanshinones to Aβ Oligomer

The experimental results from ThT binding assays, AFM, and live/dead cell assay confirm that TS1 and TS2 compounds exhibit different inhibitory abilities to prevent Aβ aggregation and reduce cell toxicity. However, atomic details of the interactions between tanshinone compounds and Aβ peptides are not yet well elucidated. To better distinguish binding modes, sites, and affinity between TS1-Aβ and TS2-Aβ and to correlate binding information with their corresponding inhibitory ability, we performed all-atom explicit-solvent MD simulations to study the interactions of Aβ pentamer with TS1 and TS2 compounds at different molar ratios of Aβ:tanshinone from 1:1 to 1:2. For convenience, the Aβ-tanshinone systems are denoted by the type of tanshinones and the number of tanshinones. For example, TS1–5 indicates that five tanshinone-I (TS1) molecules interact with Aβ pentamer, while TS2–10 indicates that ten tanshinone-IIA (TS2) molecules interact with Aβ pentamer.

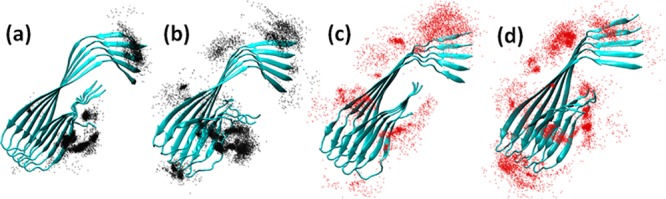

Binding Distribution

Figure 8 shows the binding distribution population of tanshinones around the Aβ pentamer, where accumulative positions of tanshinones were sampled by every 4 ps snapshots from a total of eight MD trajectories. In the bound state of TS1, TS1 tended to preferentially bind to two highly populated regions of Aβ pentamer. The first binding region was located at the external side of the hydrophobic C-terminal β-sheet. Three small G33, G37, and G38 residues sitting around M35 residues formed a kink groove, which allows TS1 to strongly interact with hydrophobic C-terminal residues. Visual inspection of MD trajectories also showed that with TS1 nestling in the major groove, the relative movement of TS1 with respect to each other became much more confined. The second region was interestingly located near the N-termini of Aβ, where was enriched with two aromatic residues of F4 and H6. Due to the restricted planar geometry of aromatic rings in both tanshinones and aromatic residues of Aβ, such ordered aromatic interactions (i.e., π–π interactions) between tanshinones and Aβ peptides could mediate specific recognition and association process of Aβ peptides, resulting in the prevention of the further growth of amyloid aggregates. A number of studies have also reported that aromatic interactions play a key role in many cases of amyloid formation,50−53 but also in the self-assembly of complex supramolecular structures.54−56 As the molar ratio of Aβ:TS1 increased from 1:1 to 1:2, three additional binding regions with initially less binding probability were intensified, which were located near a U-turn region, and S8-Y10, K16-P20 residues of the N-terminal β-sheet. In the case of TS2-Aβ systems, TS2 displayed a relative broad range of binding distributions with preferential binding near the external sides of N-/C-terminal β-sheets and U-turn region similar to TS1 binding distributions. However, the binding densities of TS2 around C-terminal region were apparently lower than those of TS1. Specifically, only limited interactions between TS2 and residues of Tyr10, His14, and Phe20 were observed. Additionally, introduction of tanshinone molecules did not disturb the structural integrity of Aβ pentamer, that is, Aβ pentamer still well retained its overall and secondary structures during 40 ns simulations. As compared to experimental observation, simulation results suggest that tanshinone-induced structural disruption of Aβ oligomers should occur in a much longer time scale. Simulation results also suggest alternative Aβ inhibition pathways. Apart from that tanshinones can directly inhibit amyloid formation by breaking the performed Aβ aggregates, tanshinones also enable to bind to β-sheets to prevent lateral association of Aβ aggregates and thus to inhibit fibril growth.57 Simulation results confirm to the experimental observation that tanshinone can not only inhibit Aβ aggregation, but also melt the mature Aβ fibrils.

Figure 8.

Binding distribution of tanshinones around Aβ pentamer for (a) TS1–5, (b) TS1–10, (c) TS2–5, and (d) TS2–10 systems. For clarity, Aβ pentamer is shown as a cartoon with cyan color, while TS1 and TS2 are represented by black and red beads, respectively.

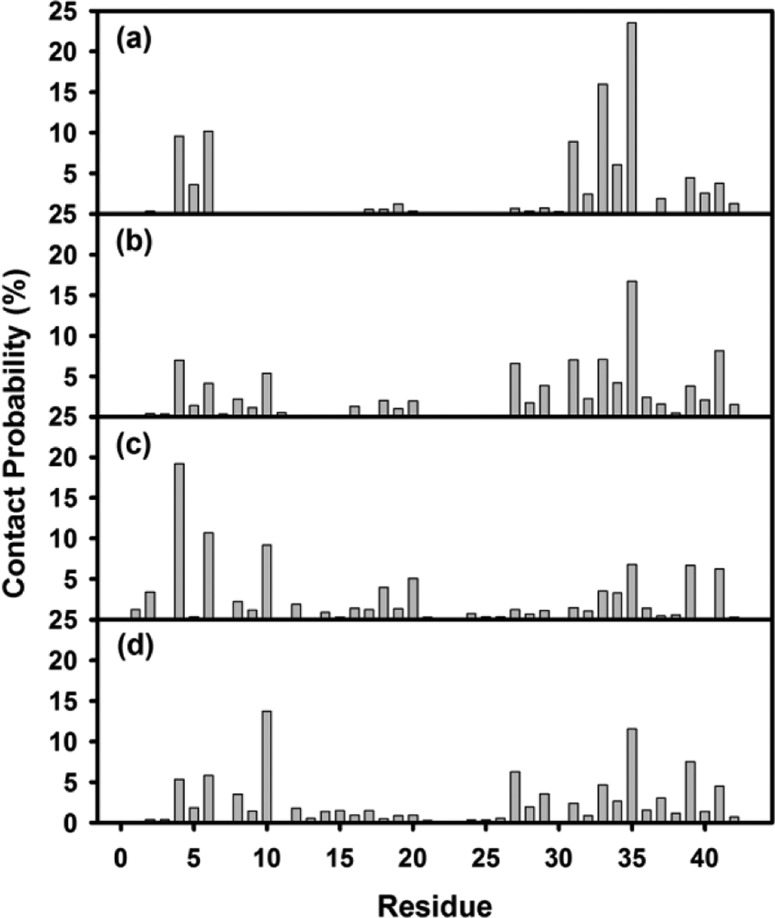

Binding Residues

To further quantitatively identify whether TS1 and TS2 have binding preferences to certain Aβ residues, we calculated the averaged contact probabilities between each Aβ residue and tanshinones based on their atomic contacts of tanshinones within 3.5 Ǻ of Aβ residues (Figure 9). Inhomogeneous contact probability between tanshinones and Aβ residues clearly indicates that tanshinones favored interactions with several Aβ residues over others. Among them, nonpolar residues, F4, H6, Y10, I31, M35, V39, and I41 generally contributed the greater binding preference to tanshinones than polar residues. Using 5% of contact probability as a threshold value, TS1 exhibited strong preferential interactions with I31 (10.1%), G33 (16.1%), M35 (23.4%), L34 (5.8%), F4 (9.7%), and H6 (10.3%). Particularly, the C-terminal residues near M35 interacted more strongly with TS1 than those N-terminal residues. For the TS2-Aβ systems, TS2 favored the interactions with I41 (6.1%), V39 (6.4%), F20 (5.6%), Y10 (9.4%), H6 (10.7%), and F4 (18.5%). Unlike TS1 showing preferential interactions with the C-terminal residues, TS2 showed strong binding preference to two hydrophobic regions of Aβ: C-terminal residues near M35 and N-terminal residues of F4, H6, and Y10. Since both TS1 and TS2 contained aromatic rings. It is not surprising that that both TS1 and TS2 had preferential interactions with hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids. Particularly, F4–H6 residues near the N-termini formed an aromatic groove, while I31-M35 at the middle of C-terminal β-sheet formed a wide hydrophobic groove. Such twisted β-sheet grooves, a signature of amyloid fibrils, provide geometrical and chemical structures to specifically interact with aromatic moieties in TS1 and TS2 via π–π stacking interactions, which enable to prevent and disrupt Aβ peptide association. In fact, many of Aβ inhibitors (e.g., Congo red and thioflavin T) that share common chemical structural features such as aromatic and/or hydrogen-bonding groups were found to specifically bind to Aβ with high affinity and thus to inhibit or delay Aβ misfolding and aggregation, suggesting the importance of aromatic groups in inhibitory ability.50−53

Figure 9.

Probabilities of atomic contacts between Aβ residues and tanshinones for (a) TS1–5, (b) TS1–10, (c) TS2–5, and (d) TS2–10 systems.

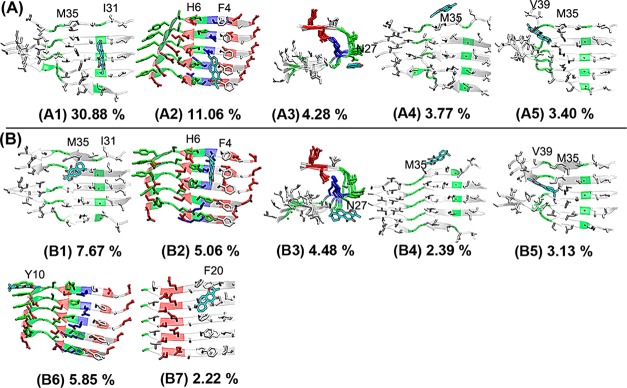

Binding Sites

To gain a more quantitative comparison of binding sites between TS1-Aβ and TS2-Aβ complexes, we clustered Aβ-tanshinone complexes into different binding groups using the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 5 Ǻ as a cutoff. Figure 10 shows different representative binding sites derived from the top Aβ-tanshinone clusters with the highest occurrence probabilities. Structural populations for the top 5 TS1 binding sites were 30.88% at the I31-M35 groove (Figure 10-A1), 11.06% at the F4-H6 groove (A2), 4.28% at N27 residues (A3), 3.77% at the M35 lateral side (A4), and 3.40% at the M35-V39 groove (A5). It can be seen clearly that the first two clusters represented the primary binding sites with a total combined binding population of 41.94% of all snapshots, while the remaining clusters presented rather diverse binding sites with relative low binding populations. In the primary binding sites, TS1 was either fitted in the C-terminal β-sheet groove formed by I31-M35 residues or aligned to aromatic residues of F4 residues. In the secondary binding sites, the populations of the remaining clusters of A3, A4, and A5 had small values of less than 5% and were similar to each other, suggesting that, despite the existence of multiple binding sites, the primary binding sites are dominant. As compared to the dominant binding sites for TS1, TS2 displayed rather diverse binding sites with similar binding populations. The top seven clustered binding sites for TS2 accounted for a total of 30.80% of all snapshots, consistent with the binding distribution of TS2 in Figure 8. Among the top seven binding sites, the first five binding sites were the same as TS1, with binding populations of 7.67% at the I31-M35 groove (Figure 10-B1), 5.06% at the F4-H6 groove (B2), 4.48% at N27 residues (B3), 2.39% at the M35 lateral side (B4), 3.13% at the M35-V39 groove (B5), while two additional binding sites were located at Y10 residues with binding population of 5.85% (B6), and at F20 residues with binding population of 2.22% (B7). The existence of negatively charged residue D22 nearby F20 created a polar environment, which may help gain more atomic contacts with TS2. TS2 binding to hydrophobic I31-M35 and M35-V39 grooves had 10.80% population, which was comparable to 13.13% population as TS2 bound to aromatic residues of F4, Y10, and F20. This fact suggests that although primary dominant binding mode for TS2 is lacking, both hydrophobic and aromatic interactions still play important roles.

Figure 10.

Representative Aβ-tanshinone binding complexes derived from the most populated clusters. (A) TS1 compounds preferentially bind to (A1) I31-M35 β-sheet groove, (A2) F4-H6 sites, (A3) U turn region around N27, (A4) the lateral side of M35, and (A5) M35-V39 sites. (B) TS2 has the same populated binding sites (B1–B5) as TS1. Two additional binding sites were identified at (B6) Y10 residues and (B7) F20 residues.

Binding Affinity

To quantify binding affinities between each binding site and tanshinones (TS1 and TS2), we used the GBMV method with the SASA correction to evaluate binding free energy between tanshinones and Aβ binding sites as summarized in Table 1. Comparison of binding affinities between different binding sites and between different tanshinone compounds reveals some interesting similarities and differences. First, all of the binding sites provided favorable binding free energies to both TS1 and TS2. Although TS1 and TS2 shared the first five common binding sites, TS1 generally had stronger binding free energies than TS2 at the four corresponding binding sites of 1, 2, 3, and 5. Second, binding affinities between different binding sites for both TS1 and TS2 were quantitatively consistent with the results obtained from binding population analysis (Figure 9). TS1 had the most favorable binding affinities at the primary binding sites of A1 and A2, while TS2 had the relatively comparable binding affinities at most of binding sites, in which the differences in binding affinities ranged from 1.4 to 7 kcal/mol. Moreover, binding to the β-sheet groove near M35 residues (sites 1, 4, 5) by tanshinones was relatively stronger than binding to the aromatic residues of phenylalanine and tyrosine at sites 2, 3, 6, or 7. Taken together, multiple binding sites with different binding populations and binding affinities suggest different routes to inhibit amyloid formation. Binding to β-sheet groove regions formed by I31-M35 and M35-V39 is to prevent the lateral association between different aggregates, while binding to turn or tail region is to disturb the local secondary structure of Aβ aggregates. Additionally, we also observed that TS1 and TS2 were able to stack on the top of each other to form a dimer or a trimer structure on the groove surface, which would provide additional steric energy barrier to prevent Aβ peptide association.

Table 1. Binding Energies (kcal/mol) for Highly Populated Binding Sites of Aβ Pentamer for TS1 and TS2a.

| site 1 | site 2 | site 3 | site 4 | site 5 | site 6 | site 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS1 | –18.9 ± 2.4 | –18.7 ± 3.2 | –17.2 ± 2.4 | –10.2 ± 1.6 | –16.7 ± 2.8 | ||

| TS2 | –14.7 ± 4.2 | –11.7 ± 3.6 | –10.1 ± 2.5 | –11.0 ± 2.2 | –16.1 ± 2.8 | –14.4 ± 2.3 | –9.1 ± 1.6 |

Binding sites are the same as those displayed in Figure 10.

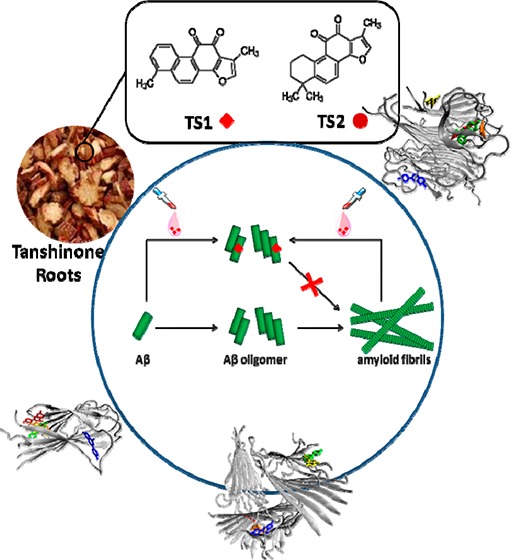

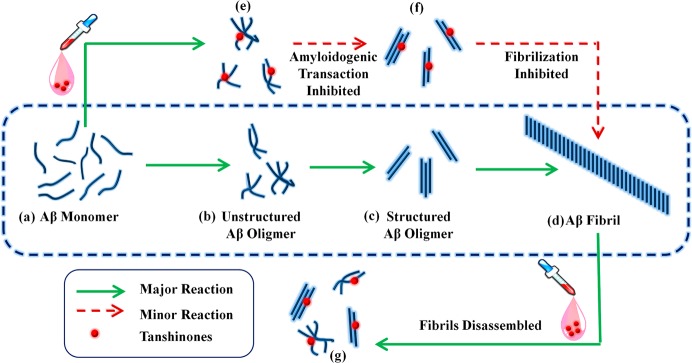

Mechanistic Model for the Inhibitory Action of Tanshinones

Based on computational and experimental results, we proposed a possible model to interpret the inhibitory and disassembling effects of tanshinones on Aβ aggregation in Figure 11. It is generally accepted that Aβ aggregation is a multiple step process, in which unstructured Aβ monomers undergo a complex conformational transition and reorgnization to form intermediate oligomers and final β-sheet-rich fibrils (a → b → c → d).58−61 Both ThT and AFM results show that TSs can prolong the nucleation process, suggesting that tanshinone can bind, at least in part, to Aβ monomers to prevent peptide association (a → e) and/or to slow down conformational transition to β-structure (e → f → d). TS1 interacts stronger with Aβ monomers than TS2 during the a → e reaction, because of enhanced binding probability at the primary binding sites of hydrophobic C-terminal I31-M35 groove (Figure 10A1, B1), which forms a steric energy barrier to prevent lateral association of Aβ peptides. Meanwhile, tanshinone could induce structural disruption to the local β-sheet of Aβ fibrils via strong binding to the turn or β-sheet groove regions of Aβ fibrils, leading to fibril disaggregation (d → g). It should be noted that, due to the hydrophobic aromatic nature and plarnar structure of tanshione, tanshiones interact with Aβ via relatively nonspecific hydrophobic interactions with β-sheet-rich side chains. This binding mode implies that tanshione could have a general inhibition potency to prevent the aggregaton of a wide range of amyloid peptides, whose aggregates adopt similar β-sheet-structures.

Figure 11.

Schematic model for the antiaggregation and disassembly effects of tanshinones on Aβ amyloid formation. Details are discussed in the text.

Conclusions

Small heterogeneous products resulted from Aβ aggregation are thought to be toxic species pathologically linked to the death of neurons in AD. Thus, the development of multifunctional inhibitors against Aβ aggregates is very critical for AD treatment. In this work, we report that tanshinones, main components extracted from Chinese herb Danshen, can inhibit Aβ aggregation, disaggregate Aβ fibers, and reduce Aβ-induced cell toxicity in vitro. ThT fluorescence binding assays and AFM confirm that both TS1 and TS2 compounds inhibit unseeded amyloid fibril formation and disaggregate Aβ amyloids. TS1 has a stronger inhibition effect than TS2, but comparable disaggregation ability to TS2, which makes tanshinones as a very few small molecules that has been shown to disaggregate preformed Aβ amyloid fibrils to date. The cell viability data show that the coincubation of Aβ with a very small amount of TSs enables protection of cultured cells from Aβ-induced toxicity by ∼57.5% for TS1 and ∼71.3% for TS2. MD simulations further reveal atomic details of tanshinones interacting with Aβ oligomer, in which both TS1 and TS2 prefer to bind to the C-terminal β-sheet, particularly hydrophobic residues I31, M35, and V39, of the Aβ pentamer. Increased molar ratio of Aβ:tanshinone from 1:1 to 1:2 has little effect on tanshinone binding sites in Aβ pentamer, suggesting that a hydrophobic groove spanning across consecutive C-terminal β-strands of Aβ pentamer represents primary tanshinone binding sites to interfere with lateral association of Aβ oligomers into higher-order aggregates. Irrespective of the details, tanshinone-derived compounds presented here constitute a new class of amyloid inhibitors with multiple advantages in amyloid inhibition, fibril disruption, and cell protection, as well as their well-known anti-inflammatory activity, which may hold great promise in treating amyloid diseases. Clearly, more in vivo studies will be required to demonstrate the pharmaceutical efficacy of tanshinones in animal tests and clinical trials, as well as other amyloid diseases.

Methods

Reagents

1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, ≥99.9%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.9%), tanshinone I (TS1, ≥97%), tanshinone IIA (TS2, ≥98%), 10 mM PBS buffer (pH = 7.4), and thioflavin T (ThT, 98%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Aβ1–42 peptide (≥95.5%) was purchased from American Peptide Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA).

Aβ1–42 Purification

Aβ1–42 peptide was obtained in lyophilized form and stored at −20 °C as arrived. In order to break the preformed Aβ aggregates into monomers, Aβ1–42 was dissolved in HFIP for 2 h, sonicated for 30 min to remove any pre-existing aggregates or seeds, and centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. And 75% of the top Aβ solution was subpackaged and frozen with liquid nitrogen and then dried with a freeze-dryer. The dry Aβ1–42 powder was lyophilized at −80 °C and used within 2 weeks.

Inhibition Assay

A homogeneous solution of Aβ monomers was required for inhibition tests. The purified Aβ1–42 powder was aliquoted in DMSO for 1 min and sonicated for 30 s. The initiation of 20 μM Aβ1–42 [containing 1% (v/v) DMSO] aggregation in solution was accomplished by adding an aliquot of the concentrated DMSO-Aβ1–42 solution to 10 mM PBS buffer, followed by immediate vortexing to mix thoroughly. Aβ1–42 solution was then centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C to remove any existing oligomers, and 75% of the top solution was removed for further incubation or inhibition experiments. The pure Aβ1–42 solution was incubated at 37 °C as control. For Aβ inhibition experiments, 40 mM tanshinone (in DMSO) stock solution was dissolved in freshly prepared Aβ1–42 monomer solution to a final concentration of 20 and 40 μM (with Aβ:tanshinone molar ratios of 1:1 and 1:2). The mixed Aβ-tanshinone samples were incubated at 37 °C.

Disruption Assay of Aβ Fibrils

Aβ1–42 fibrils were prepared by incubating 20 μM Aβ1–42 monomers for 48 h, which is sufficiently long enough to enable Aβ peptides to grow into mature fibrils at a saturate state. The fibril solution was then divided into aliquots for the disruption tests. To examine the effect of Aβ:tanshinone molar ratios on the extent of disruption of Aβ fibrils and to determine the minimal usage of tanshinone for more effective disruption of Aβ fibrils, 40 mM tanshinone (in DMSO) stock solution was dissolved in the Aβ fibril solution at different Aβ:tanshinone molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5. All the disruption samples were incubated at 37 °C.

Thioflavine T (ThT) Fluorescence Assay

Aβ1–42 fibrillization and Aβ1–42 fibril disruption in the presence and absence of tanshinones were monitored by ThT fluorescence assay. ThT store solution (2 mM) was prepared by adding 0.0328 g of ThT powder into 50 mL of DI water. Then 250 μL of the 2 mM ThT solution was further diluted into 50 mL of Tris-buffer (pH = 7.4) to reach a final concentration of 10 μM. A volume of 60 μL of 20 μM Aβ with or without tanshinone was put into 3 mL of 10 μM ThT-Tris solution. Fluorescence spectra were obtained using a LS-55 fluorescence spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Waltham, MA). All measurements were carried out in aqueous solution using a 1 cm × 1 cm quartz cuvette. ThT fluorescence emission intensity of each sample was recorded between 460 and 510 nm with an excitation wavelength of 450 nm. Fluorescence intensity from solution without Aβ1–42 was subtracted from solution containing Aβ1–42. Each experiment was repeated in three independent samples, and each sample was tested in quadruplicate.

Tapping-Mode AFM

The morphology change of Aβ fibrillization and disruption in the presence and absence of tanshinones was characterized by AFM. A 25 μL sample used in the Aβ1–42 ThT fluorescence assay was taken for AFM measurement at different time points to correlate Aβ morphology change with Aβ growth kinetics. Aβ1–42 solution with/without tanshinones was deposited onto a freshly cleaved mica substrate for 1 min, rinsed three times with 50 mL of deionized water to remove salts and loosely bound Aβ, and dried with compressed air for 5 min before AFM imaging. Tapping mode AFM imaging was performed in air using a Nanoscope III multimode scanning probe microscope (Veeco Corp., Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a 15 μm E scanner. Commercial Si cantilevers (NanoScience) with an elastic modulus of ∼40 N m–1 were used. All images were acquired as 512 × 512 pixel images at a typical scan rate of 1.0–2.0 Hz with a vertical tip oscillation frequency of 250–350 kHz. Representative AFM images were obtained by scanning at least six different locations of different samples.

Cell Culture

All chemicals for cell culture were purchased from Life Technologies unless otherwise stated. Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was used as model neuron and cultured in 75 cm2 T-flasks (Corning) in sterile-filtered Eagle’s minimum essential medium and Ham’s F-12 medium mixed at a 1:1 ratio containing 10% fetal bovine serum (EMEM, ATCC, Manassas, VA,), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in 37 °C, humidified air with 5% CO2. Cells were cultured to confluence and harvested using 0.25 mg/mL Trypsin/EDTA solution (Lonza). Before adding Aβ and tanshinone, cells were resuspended in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium and counted using a hemacytometer. Cells were then plated in a 24-well tissue culture plate with approximately 150 000 cells per well in 500 μL of Opti-MEM reduced serum medium and then allowed to attach for 24 h inside the incubator.

Live/Dead Cell Toxicity Assay

Aβ oligomers were prepared by incubating a 1 mM Aβ-PBS solution at 37 °C for 24 h. Aβ oligomers with a molar ratio of Aβ:tanshinone of 1:0.2 were added to each well to reach a final concentration of 20 μM. The cells were then left for 24 h before cell toxicity tests. A live/dead cytotoxicity assay, which determines live and dead cells with two probes by measuring intracellular esterase activity and plasma membrane integrity, was used to obtain cell viability/toxicity data. Cells were stained by adding 2 μM Calcein AM (Life Technologies) to distinguish the presence of live cells with a fluorescence excitation/emission of 494/517 nm, while by adding 5 μM of Ethidium homodimer-1 (Life Technologies) to distinguish the presence of dead cells with a fluorescence excitation/emission of 528/617 nm. The cells were incubated for 15 min with the live/dead assay contents to activate the fluorescent dyes. A Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL inverted microscope fitted with filters at 510 and 600 nm was used to obtain fluorescence images of the live and dead cells. Fluorescence readings at 494/517 nm and 528/617 nm were detected using a Synergry H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Cell death in each incubation condition was normalized using the equation of ΔF = (Fi/FAβ) × 100%, where ΔF is the percentage of cell death in different incubation conditions compared with the death of cells coincubate with Aβ. Fi corresponds to the dead/live fluorescence signal of cells (blank control), cells coincubate with TS1, cells coincubate with TS2, cells coincubate with Aβ and TS1, cells coincubate with Aβ and TS2, and cells coincubate with Aβ, respectively. FAβ represents the dead/live fluorescence signal of cells coincubate with Aβ. The fluorescence signals of blank dyes were calibrated first and then subtracted from the fluorescence signals of medium solution.

Aβ-Tanshinone Simulation Systems

Initial atomic structure of Aβ9–40 monomer was obtained from Dr. Tycko’s lab by averaging NMR-derived Aβ 18-mer.62,63 Since the residues 1–8 are structurally disordered and residues 41–42 are missing, the structural coordinates of residues 1–8 and 41–42 were constructed as an extend conformation and then reassembled into the β-hairpin structure of Aβ9–40, yielding a full-length Aβ1–42 monomer with the U-shaped β-strand-turn-β-strand conformation. The Aβ1–42 monomer consisted of two β-strands, β1 (residues V1–S26) and β2 (residues I31-A42), connected by a U-bent turn spanning four residues N27-A30. D23 and K28 formed an intrastrand salt bridge to stabilize this U-bent structure. Since Aβ1–42 prefers to aggregate into pentamer and hexamer at the early assembly of Aβ42 oligomerization,64,65 Aβ1–42 pentamer was used as a typical and toxic oligomer to interact with TS1 and TS2 to determine potential binding sites and underlying inhibition mechanism. An Aβ1–42 pentamer was constructed by longitudinally stacking Aβ1–42 monomers on top of each other in a parallel and register manner, with an initial peptide–peptide separation distance of ∼4.7 Ǻ, corresponding to experimental data.62,63 Aβ peptide was carboxylated and amidated at the N- and C- terminus, respectively, yielding a total net negative charge of −15 e for Aβ pentamer.

Initial geometrical coordinates of TS1 and TS2 were determined and optimized at the MP2/6-31G* level by Gaussian03.66 After geometry optimization, the partial charges of TS1 and TS2 were derived by fitting to the gas-phase electrostatic potential using the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) method. Then, atomic structures of TS1 and TS2 obtained from Gaussian03 were subject to the ParamChem tool (https://www.paramchem.org/) to develop the force field parameters for TS1 and TS2, which are compatible with the CHARMM general force field.67 The partial charges of TS1 and TS2 were further optimized by fitting the tanshinine-TIP3P water interaction energy. To validate the force field parameters of TS1 and TS2, short 2 ns MD simulations of single TS1 or TS2 in a TIP3P water box were conducted at 310 K. The bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles were well maintained in the MD simulations as compared to quantum mechanism structure. The topology structure, charge distribution, bonded and nonbonded parameters of TS1 and TS2 in CHARMM format are provided in the Supporting Information.

Two different molar ratios of Aβ:tanshinone (1:1 and 1:2) were used to examine the concentration effect of tanshinones on Aβ-tanshinone binding interactions and underlying tanshinone inhibition mechanisms. Five or ten tanshinones were initially and randomly placed around Aβ pentamer at a minimum distance of 10 Å, which allows the tanshinones to unbiasedly search and sample binding sites around Aβ. Each Aβ-tanshinone system was solvated in a rectangular TIP3P water box. Any water molecule within a radius of 2.4 Å from the non-hydrogen atoms of the solute (Aβ, TS1, or TS2) was deleted. Counter ions (Na+ and Cl–) were added to the simulation box to achieve electro neutrality and ionic strength of ∼100 mM.

MD Simulation Protocol

Simulations of Aβ-tanshinone in explicit water molecules and counterions were performed using the NAMD program68 with CHARMM27 force fields.69 Each Aβ-tanshinone system was first subject to 5000 steps of steepest descent minimization with position constraints on Aβ and tanshinones, followed by additional 5000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization without any position constraint. After energy minimization, the system was then gradually heated from 50 to 500 K in 200 ps to randomize the positions of tanshinones. The systems were then equilibrated at 310 K and 1 atm for 1 ns to adjust system size and water density under NPT ensemble with the heavy-atom coordinates of Aβ and tanshinones being constrained. Then, 40 ns MD runs were conducted to examine the mutual structural dynamics and binding events between Aβ and tanshinone. Short-range VDW interactions were calculated by a switch function with a twin cutoff at 10 and 12 Å, while long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated by the particle-mesh Ewald method with a grid size of ∼1 Ǻ and a real-space cutoff of 14 Ǻ. The RATTLE algorithm was applied to constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms, so that a time step of 2 fs was used in velocity verlet integration. Two independent simulations of each system were run to assess simulation reproducibility using different starting coordinates and velocities. MD trajectories were saved by every 2 ps for analysis.

Aβ-Tanshinone Binding Free Energy

Binding free energies of tanshinones to Aβ pentamer were evaluated on the representative clusters using the MM-GBMV (molecular mechanism-generalized born with molecular volume) method as implemented in CHARMM.70 In this method, the total binding free energy in water is approximately calculated by ΔEtot = Ecomplex – EAβ – Ets. Each energy term (Ecomplex, EAβ, or Ets) is estimated as the sum of the gas phase energy (Egas) and the solvation energy (Esolv), according to Ei = ⟨ΔEgas⟩ + ⟨ΔEsol⟩, where brackets ⟨...⟩ indicate an average energy term sampled from MD trajectories. Egas contains conventional bonded (i.e., bond, angle, and torsion) and nonbonded (VDW and electrostatics) interactions, as shown eq 1.

| 1 |

Esolv contains polar solvation energy (Eps) and nonpolar solvation energy (Enps) (eq 2).

| 2 |

Eps is calculated by solving the linear Poisson–Boltzmann equation using generalized born method of the CHARMM program. Enps is calculated by Enps = γSASA, where SASA (solvent-accessible surface area) is calculated using a water probe radius of 1.4 Ǻ and γ is set to 0.00542 kcal/mol.71 The solute and solvent dielectric constants were set to 1 and 80, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Resource for Biomedical Supercomputing and the Ohio Supercomputer Center for (in part) utilizing their supercomputing facilities for the simulation work.

Supporting Information Available

A complete set of CHARMM force field parameters for tanshinone TS1 and TS2 compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

Q.W. and X.Y. contributed equally to this work. Q.W., X.Y., G.Z., and J.Z. designed research; Q.W., X.Y., K.P., and R.H. performed research; Q.W., X.Y., K.P., and R.H. analyzed data; Q.W., X.Y., S.C., G.Z., and J.Z. wrote the paper.

J.Z. thanks the support from NSF grants (CAREER Award CBET-0952624 and CBET-1158447).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Brookmeyer R.; Johnson E.; Ziegler-Graham K.; Arrighi H. M. (2007) Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia 3, 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T.; Kienlen-Campard P.; Ahmed M.; Liu W.; Li H.; Elliott J. I.; Aimoto S.; Constantinescu S. N.; Octave J. N.; Smith S. O. (2006) Inhibitors of amyloid toxicity based on beta-sheet packing of Abeta40 and Abeta42. Biochemistry 45, 5503–5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe C. C. (2005) Amyloid accumulation and pathogensis of Alzheimer’s disease: significance of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Abeta. Subcell. Biochem. 38, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J.; Selkoe D. J. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom G. S.; Ren K.; Glabe C. G. (2005) Cultured cell and transgenic mouse models for tau pathology linked to beta-amyloid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1739, 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P. K.; Moore A. N.; Orsi S. A. (2005) Blockade of [gamma]-secretase activity within the hippocampus enhances long-term memory. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai M.; Hattori C.; Iwata N.; Saido T. C.; Sasagawa N.; Szabó B.; Hashimoto Y.; Maruyama K.; Tanuma S.-i.; Kiso Y.; Ishiura S. (2006) The novel beta-secretase inhibitor KMI-429 reduces amyloid beta peptide production in amyloid precursor protein transgenic and wild-type mice. J. Neurochemistry 96, 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacskai B. J.; Kajdasz S. T.; Christie R. H.; Carter C.; Games D.; Seubert P.; Schenk D.; Hyman B. T. (2001) Imaging of amyloid-[beta] deposits in brains of living mice permits direct observation of clearance of plaques with immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 7, 369–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härd T.; Lendel C. (2012) Inhibition of amyloid formation. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 441–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield S.; Hejjaoui M.; Fauvet B.; Awad L.; Lashuel H. A. (2012) Chemical strategies for controlling protein folding and elucidating the molecular mechanisms of amyloid formation and toxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 204–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbich C.; Kisterswoike B.; Reed J.; Masters C. L.; Beyreuther K. (1992) Substitutions of Hydrophobic Amino-Acids Reduce the Amyloidogenicity of Alzheimers-Disease Beta-A4 Peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 228, 460–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary J. P.; Walsh D. M.; Hofmeister J. J.; Shankar G. M.; Kuskowski M. A.; Selkoe D. J.; Ashe K. H. (2005) Natural oligomers of the amyloid-[beta] protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeis M. A. (2000) Approaches to discovery and characterization of inhibitors of amyloid β-peptide polymerization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 1502, 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C.; Sigurdsson E. M.; Morelli L.; Kumar R. A.; Castaño E. M.; Frangione B. (1998) Beta-sheet breaker peptides inhibit fibrillogenesis in a rat brain model of amyloidosis: implications for Alzheimer’s therapy. Nat. Med. 4, 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Leibowitz M. J.; Sinko P. J.; Stein S. (2003) Multiple-peptide conjugates for binding beta-amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioconjugate Chem. 14, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai A. S.; Rubinstein I.; Onyuksel H. (2006) PEGylated phospholipid nanomicelles interact with beta-amyloid((1–42)) and mitigate its beta-sheet formation, aggregation and neurotoxicity in vitro. Peptides 27, 2858–2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaleiro-Lago C.; Quinlan-Pluck F.; Lynch I.; Lindman S.; Minogue A. M.; Thulin E.; Walsh D. M.; Dawson K. A.; Linse S. (2008) Inhibition of amyloid beta protein fibrillation by polymeric nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15437–15443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. I.; Yang M.; Brender J. R.; Subramanian V.; Sun K.; Joo N. E.; Jeong S. H.; Ramamoorthy A.; Kotov N. A. (2011) Inhibition of Amyloid Peptide Fibrillation by Inorganic Nanoparticles: Functional Similarities with Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50, 5110–5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. E.; Lee M. (2003) Fullerene inhibits beta-amyloid peptide aggregation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 303, 576–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson L. P.; Smith N. W.; Dzyuba S. V. (2012) Dye-binding assays for evaluation of the effects of small molecule inhibitors on amyloid (Aβ) self-assembly. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 3, 807–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M.; Suzuki N.; Taniguchi S.; Oikawa T.; Nonaka T.; Iwatsubo T.; Hisanaga S.-i.; Goedert M.; Hasegawa M. (2006) Small molecule inhibitors of α-synuclein filament assembly. Biochemistry 45, 6085–6094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelle G.; Otto A.; Lorenz M.; Frank R. F.; Wanker E. E.; Bieschke J. (2011) Black tea theaflavins inhibit formation of toxic amyloid-β and α-synuclein fibrils. Biochemistry 50, 10624–10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P.; Raleigh D. P. (2012) Analysis of the inhibition and remodeling of islet amyloid polypeptide amyloid fibers by flavanols. Biochemistry 51, 2670–2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B.; Liu X.; Gong H.; Huang L.; Chen H.; Zhang X.; Li C.; Yang M.; Ma B.; Jiao L.; Zheng L.; Huang K. (2011) Coffee components inhibit amyloid formation of human islet amyloid polypeptide in vitro: possible link between coffee consumption and diabetes mellitus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 13147–13155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Yu X., Li L., and Zheng J.. Inhibition of amyloid-β aggregation in Alzheimer disease. Curr. Pharm. Des., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M.; Kalaria R. N.; Cras P.; Siedlak S. L.; Velasco M. E.; Shelton E. R.; Chan H. W.; Greenberg B. D.; Perry G. (1993) Degeneration of vascular muscle cells in cerebral amyloid angiopathy of Alzheimer disease. Brain Res. 623, 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise R.; Mateo V.; Rouxel C.; Zaccarini F.; Glorian M.; Béréziat G.; Golubkov V. S.; Limon I. (2012) Wild-type amyloid beta 1–40 peptide induces vascular smooth muscle cell death independently from matrix metalloprotease activity. Aging Cell 11, 384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. (2001) Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81, 741–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Zheng L. L.; Wang F.; Hu Z. L.; Wu W. N.; Gu J.; Chen J. G. (2011) Tanshinone IIA attenuates neuronal damage and the impairment of long-term potentiation induced by hydrogen peroxide. J. Ethnopharmacol. 134, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas C. Jr.; Bolzani Vda S.; Barreiro E. J.; Fraga C. A. (2005) New anti-Alzheimer drugs from biodiversity: the role of the natural acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 5, 915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. M.; Zuo Z.; Chow M. S. S. (2005) Danshen: An overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45, 1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Gao X.; Zhang B. (2005) Tanshinone: an inhibitor of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 99, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan A. K.; Leung S. W.; Zhu D. Y.; Man R. Y. (2008) Vascular effects of different lipophilic components of “Danshen”, a traditional Chinese medicine, in the isolated porcine coronary artery. J. Nat. Prod. 71, 1825–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y. F.; Xu H. W.; Liu X. Q.; Zhang X. J.; Wang Z. J.; Liu H. M. (2010) Synthesis and vasodilative activity of tanshinone IIA derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 4892–4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. G.; Song Y. M.; Yang Y. Y.; Liu W. F.; Tang J. X. (1979) [Pharmacology of tanshinone (author’s transl)]. Yao Xue Xue Bao 14, 75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. L.; Yang W. N.; Chen X. L.; Zhang J. S.; Yang P. B.; Hu X. D.; Han H.; Qian Y. H.; Liu Y. (2012) The protective effects of tanshinone IIA on neurotoxicity induced by beta-amyloid protein through calpain and the p35/Cdk5 pathway in primary cortical neurons. Neurochem. Int. 61, 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. X.; Dai J. P.; Ru L. Q.; Yin G. F.; Zhao B. (2004) Effects of tanshinone on neuropathological changes induced by amyloid beta-peptide(1–40) injection in rat hippocampus. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 25, 861–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia W. J.; Yang M.; Fok T. F.; Li K.; Chan W. Y.; Ng P. C.; Ng H. K.; Chik K. W.; Wang C. C.; Gu G. J.; Woo K. S.; Fung K. P. (2005) Partial neuroprotective effect of pretreatment with tanshinone IIA on neonatal hypoxia-ischemia brain damage. Pediatr. Res. 58, 784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafekar S. M.; Malda H.; Merkx M.; Meijer E. W.; Viertl D.; Lashuel H. A.; Baas F.; Scheper W. (2007) Branched KLVFF tetramers strongly potentiate inhibition of beta-amyloid aggregation. ChemBioChem 8, 1857–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. L.; Ha H.; Chang Y. T.; DeLisa M. P. (2009) Discovery of amyloid-beta aggregation inhibitors using an engineered assay for intracellular protein folding and solubility. Protein Sci. 18, 277–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourhim M.; Kruzel M.; Srikrishnan T.; Nicotera T. (2007) Linear quantitation of Abeta aggregation using Thioflavin T: reduction in fibril formation by colostrinin. J. Neurosci. Methods 160, 264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B. Y.; Toyama B. H.; Wille H.; Colby D. W.; Collins S. R.; May B. C.; Prusiner S. B.; Weissman J.; Shoichet B. K. (2008) Small-molecule aggregates inhibit amyloid polymerization. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 197–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stains C. I.; Mondal K.; Ghosh I. (2007) Molecules that target beta-amyloid. ChemMedChem 2, 1674–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard B. J.; Chen A.; Rozeboom L. M.; Stafford K. A.; Weigele P.; Ingram V. M. (2004) Efficient reversal of Alzheimer’s disease fibril formation and elimination of neurotoxicity by a small molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 14326–14332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood A.; Abid M.; Sauer C.; Hailemichael S.; Foster M.; Torok B.; Torok M. (2011) Disassembly of preformed amyloid beta fibrils by small organofluorine molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 2044–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. J.; Sciarretta K. L.; Meredith S. C. (2001) Inhibition of beta-amyloid(40) fibrillogenesis and disassembly of beta-amyloid(40) fibrils by short beta-amyloid congeners containing N-methyl amino acids at alternate residues. Biochemistry 40, 8237–8245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C.; Hou Y.; Han Y.; Wang Y. (2011) Disassembly of amyloid fibrils by premicellar and micellar aggregates of a tetrameric cationic surfactant in aqueous solution. Langmuir 27, 4551–4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Zhu M.; Manning-Bog A. B.; Di Monte D. A.; Fink A. L. (2004) Dopamine and L-dopa disaggregate amyloid fibrils: implications for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 18, 962–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. M.; Chi X.; Hellermann G.; Sutton E. T. (2001) Physiological levels of beta-amyloid induce cerebral vessel dysfunction and reduce endothelial nitric oxide production. Neurol. Res. 23, 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. (2006) Consensus features in amyloid fibrils: sheet-sheet recognition via a (polar or nonpolar) zipper structure. Phys. Biol. 3, P1–P4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach J. J.; Ishii Y.; Antzutkin O. N.; Leapman R. D.; Rizzo N. W.; Dyda F.; Reed J.; Tycko R. (2000) Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16–22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry 39, 13748–13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazit E. (2002) A possible role for pi-stacking in the self-assembly of amyloid fibrils. FASEB J. 16, 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azriel R.; Gazit E. (2001) Analysis of the minimal amyloid-forming fragment of the islet amyloid polypeptide. An experimental support for the key role of the phenylalanine residue in amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34156–34161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens C. G.; Stoddart J. F. (1997) π–π interactions in self-assembly. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 10, 254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Burley S.; Petsko G. (1985) Aromatic-aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science 229, 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C.-J.; Zheng J.; Nussinov R. (2006) Designing a nanotube using naturally occurring protein building blocks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2, e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Ma B.; Chang Y.; Nussinov R. (2008) Molecular dynamics simulations of alzheimer’s peptide A[beta]40 elongation and lateral association. Front. Biosci. 13, 3919–3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer S.; Meersman F.; Dobson C. M.; Vendruscolo M. (2008) A generic mechanism of emergence of amyloid protofilaments from disordered oligomeric aggregates. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellermann G. P.; Byrnes H.; Striebinger A.; Ullrich K.; Mueller R.; Hillen H.; Barghorn S. (2008) Abeta-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Han S.; Zhou F.; Carter S. A.; Fink A. L. (2004) Annular oligomeric amyloid intermediates observed by in situ atomic force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24452–24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Shah N.; Zhao J.; Wang C.; Zhao C.; Liu L.; Li L.; Zhou F.; Zheng J. (2011) Structural, morphological, and kinetic studies of beta-amyloid peptide aggregation on self-assembled monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 15200–15210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A. T.; Yau W. M.; Tycko R. (2006) Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 45, 498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paravastu A. K.; Petkova A. T.; Tycko R. (2006) Polymorphic fibril formation by residues 10–40 of the alzheimer’s {beta}-amyloid peptide. Biophys. J. 90, 4618–4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G.; Kirkitadze M. D.; Lomakin A.; Vollers S. S.; Benedek G. B.; Teplow D. B. (2003) Amyloid beta -protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 330–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B.; Cruz L.; Yun S.; Buldyrev S. V.; Bitan G.; Teplow D. B.; Stanley H. E. (2004) In silico study of amyloid {beta}-protein folding and oligomerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17345–17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Montgomery J. A. Jr., Vreven T., Kudin K. N., Burant J. C., Millam J. M., Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J., Barone V., Mennucci B., Cossi M.; Scalmani G., Rega N., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Klene M., Li X., Knox J. E., Hratchian H. P., Cross J. B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R. E., Yazyev O., Austin A. J., Cammi R.; Pomelli C., Ochterski J. W., Ayala P. Y., Morokuma K., Voth G. A.; Salvador P., Dannenberg J. J., Zakrzewski V. G., Dapprich S., Daniels A. D., Strain M. C., Farkas O., Malick D. K., Rabuck A. D., Raghavachari K.; Foresman J. B., Ortiz J. V., Cui Q., Baboul A. G., Clifford S., Cioslowski J., Stefanov B. B., Liu G., Liashenko A., Piskorz P., Komaromi I., Martin R. L., Fox D. J., Keith T., Al-Laham M. A., Peng C. Y., Nanayakkara A., Challacombe M., Gill P. M. W., Johnson B., Chen W., Wong M. W., Gonzalez C., and Pople J. A. (2004) Gaussian 03, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K.; Hatcher E.; Acharya C.; Kundu S.; Zhong S.; Shim J.; Darian E.; Guvench O.; Lopes P.; Vorobyov I.; Mackerell A. D. Jr. (2010) CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 671–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale L.; Skeel R.; Bhandarkar M.; Brunner R.; Gursoy A.; Krawetz N.; Phillips J.; Shinozaki A.; Varadarajan K.; Schulten K. (1999) NAMD2: greater scalability for parallel molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 151, 283–312. [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell A. D.; Bashford D.; Bellott M.; Dunbrack R. L.; Evanseck J. D.; Field M. J.; Fischer S.; Gao J.; Guo H.; Ha S.; Joseph-McCarthy D.; Kuchnir L.; Kuczera K.; Lau F. T. K.; Mattos C.; Michnick S.; Ngo T.; Nguyen D. T.; Prodhom B.; Reiher W. E.; Roux B.; Schlenkrich M.; Smith J. C.; Stote R.; Straub J.; Watanabe M.; Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J.; Yin D.; Karplus M. (1998) All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S.; Feig M.; Salsbury F. R.; Brooks C. L. (2003) New analytic approximation to the standard molecular volume definition and its application to generalized born calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1348–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raha K.; Merz K. M. Jr. (2005) Large-scale validation of a quantum mechanics based scoring function: predicting the binding affinity and the binding mode of a diverse set of protein-ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 48, 4558–4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.