Abstract

Objective

To investigate smoking prevalence and cessation services provided by male physicians in hospitals in three Chinese cities.

Methods

Data were collected from a survey of male physicians employed at 33 hospitals in Changsha, Qingdao and Wuxi City (n=720). Exploratory factor analysis was performed to identify latent variables, and confirmatory structural equation modelling analysis was performed to test the relationships between predictor variables and smoking in male physicians, and their provision of cessation services.

Results

Of the sampled male physicians, 25.7% were current smokers, and 54.0% provided cessation services by counselling (18.8%), distributing self-help materials (17.1%), and providing traditional remedies or medication (18.2%). Factors that predicted smoking included peer smoking (OR 1.14 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26) and uncommon knowledge (OR 0.94 95% CI 0.89 to 0.99), a variable measuring awareness of the association of smoking with stroke, heart attack, premature ageing and impotence in male adults as well as the role of passive smoking in heart attack. Factors that predicted whether physicians provided smoking cessation services included peer smoking (OR 0.82 95% CI 0.76 to 0.89), physicians’ own smoking (OR 0.87 95% CI 0.81 to 0.93), training in cessation (OR 1.36 95% CI 1.27 to 1.45) and access to smoking cessation resources (OR 1.69 95% CI 1.58 to 1.82).

Conclusions

The smoke-free policy is not strictly implemented at healthcare facilities, and smoking remains a public health problem among male physicians. A holistic approach, including a stricter implementation of the smoke-free policy, comprehensive education on the hazards of smoking, training in standard smoking-cessation techniques and provision of cessation resources, is needed to curb the smoking epidemic among male physicians and to promote smoking cessation services in China.

Keywords: Cessation, Global health, Public policy, Health Services

Introduction

China is the world's largest consumer of tobacco, and 52.9% of its men are smokers.1 China is burdened by smoking-related illnesses that result in about a million deaths each year.2 3 At the current rate, the expected burden is predicted to increase to 3 million deaths annually by the year 2040.4 WHO warning that cigarette smoking was a time bomb for 21st-century China was no exaggeration.4

Smoking among physicians is of particular concern, considering their crucial role in the fight against tobacco use.5–8 Physicians are widely viewed as role models for healthy lifestyles by their patients and the general population,9 and convincing the public not to smoke is difficult when they frequently witness physicians smoking in healthcare settings.10 In other nations, research has shown that compared with physicians who smoke, non-smoking physicians are more likely to identify the smoking status of their patients, provide advice on quitting and thorough cessation counselling coverage,11 and initiate cessation interventions.12 They are also more effective at persuading their patients to quit smoking.13 Despite the important role of physicians in tobacco control, a large proportion of male physicians in China are smokers; but smoking prevalence among female physicians is very low, reflecting low prevalence among women at large in China.4 Previous studies have shown that smoking rates among male physicians range between 26% and 61%.2 4 6 14 15

In an effort to curb the smoking pandemic among medical professionals and to create smoke-free healthcare facilities, the Chinese Ministry of Health and several other national agencies issued a joint ministerial decision entitled ‘Decision to Ban Smoking Completely in the Medical and Health System by 2011,’16 which imposed a ban on smoking inside health administration office buildings and required at least 50% of all healthcare facilities to be smoke-free by the end of 2010 and the remaining by the end of 2011. An implementation plan to meet the requirements of the ministerial decision was issued by the Ministry of Health in an official document, accompanied by a scoring table that required healthcare facilities to gain 80 out of 120 points in order to reach the required smoke-free standard.17 To date, little is known about whether this requirement has been implemented and how this may have impacted both smoking and the provision of cessation services among medical professionals in China.18 Evidence from other countries has suggested that implementation of such a nationwide mandated hospital smoking ban contributes to the improvement of the environment in healthcare facilities and brings about significant changes in smoking behaviours among hospital employees.19 20

In the present study, we examined data from a recent tobacco control programme targeting medical professionals. Our main purpose was to investigate the prevalence of, and variables associated with, smoking among male physicians and their practice of cessation services after the joint ministerial decision.

Methods

Sample and data

The study sample was drawn from a survey conducted between May and August 2011 among physicians in three major cities in China: Changsha, Wuxi and Qingdao. Changsha is a city in the central part of China with a population of 7 million; Wuxi is located in the southeast China with nearly 6.4 million urban residents, and Qingdao is a major coastal city lying across the Shandong Peninsula with a population of 8.7 million. The three cities are among the 17 city grantees of the Emory Global Health Institute-China Tobacco Control Partnership Program launched in 2009 with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with the aim of changing the social norms on tobacco use in China.21 Each city grantee determined the focus of its tobacco control efforts based on its unique resources and situation. The cities of Changsha, Wuxi and Qingdao targeted hospitals and community clinics.

The survey was conducted at 33 hospitals selected from the three cities with stratified cluster sampling. For each selected hospital, about 15%–20% of all full-time medical professionals whose names were listed with a pseudorandom number were randomly selected to complete the self-administered questionnaire, adapted from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey and validated in China in previous studies.22 Extensive information, including smoking-related health knowledge, behaviours, implementation of smoke-free hospital policy, training in smoking cessation services, availability of smoking cessation resources and practice of cessation services, was collected. The protocol of the current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Emory University in the USA and a similar board at the local Center for Disease Control. A total of 2288 physicians completed the survey: 720 men and 1568 women. Because of the low smoking prevalence of female physicians (1.3%) in the sample, our analysis was restricted to male physicians (n=720).

Variables

Besides the two key variables of current smoking status of physicians and their cessation services, multiple variables were selected a priori for analysis based on hypothesised relationships with the key outcome variables, which are presented below.

Demographic variables

Age was categorised as <30, 30–39, 40–49 and 50 years and older. Education was coded into three levels: high school and below, college, and postgraduate. Marital status was categorised as married versus single/divorced/widowed.

Smoking status of peers

Smoking by coworkers was measured by the following question: During the past 30 days, did any of your coworkers smoke in indoor areas where you work? A dummy variable was generated based on the response (yes or no).

Training in smoking cessation and access to cessation resources

Physicians reported whether they have ever received training in smoking cessation at special conferences, symposia, or workshops and whether they had resources, including self-help materials and medications, available at their hospital to help patients quit smoking. Responses to both questions were dichotomised as yes or no.

Smoking status

Current smoking status of physicians was measured with the following question: Do you currently smoke tobacco on a daily basis, less than daily or not at all? Daily smokers and occasional smokers were coded as current smokers in contrast to physicians who never smoked or were former smokers.

Provision of smoking cessation services

Provision of smoking cessation services was identified by asking the following question: Do you use any intervention including counselling, self-help materials, traditional remedies and medication to help your patients quit smoking? Responses were dichotomised as yes (ie, use of any intervention by the respondent) or no.

Health knowledge of harms of active and passive smoking

In the survey, questions were asked regarding physicians’ health knowledge of the harms of active and passive smoking—Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cause the following problems: stroke, heart attack, lung cancer, emphysema, yellow teeth, impotence in male smokers or premature ageing? And Based on what you know or believe, does secondhand smoke cause the following diseases: heart attack in adults, lung illnesses in children or lung cancer in adults? Physicians responded yes or no on whether smoking causes each of the 10 diseases/symptoms.

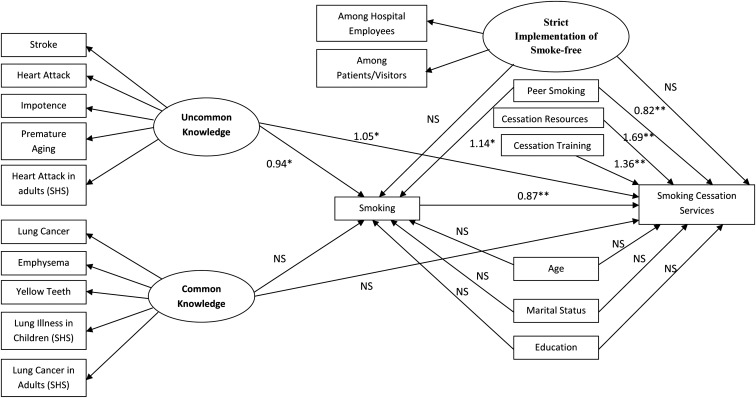

The exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation divided these 10 indicators (Cronbach's α coefficient=0.88) of knowledge regarding the harms of smoking into two latent variables/factors (table 1). The first factor (labelled uncommon knowledge in figure 1), which included five measured variables (smoking may cause stroke, smoking may cause heart attack, smoking may cause impotence, smoking may cause premature ageing and secondhand smoking may cause heart attack in adults), accounted for 36.09% of the variance in the model; and the second factor (labelled common knowledge), which included another five observed variables (smoking may cause lung cancer, smoking may cause emphysema, smoking may cause yellow teeth, secondhand smoking may cause lung illness in children and secondhand smoking may cause lung cancer in adults), accounted for 29.56% of the variance. As shown in table 1, the observed variables had a rotated factor loading, ranging from 0.754 to 0.819 for the first latent factor (uncommon knowledge) and from 0.639 to 0.839 for the second latent factor (common knowledge). All the loadings were considered strong compared with the commonly used cut-off point of 0.3 or 0.4.23

Table 1.

Results of the factor analysis of knowledge regarding hazards of smoking and passive smoking (secondhand smoking, SHS) (N=720)

| Rotated factor pattern | ||

|---|---|---|

| Items | Factor 1 (uncommon knowledge) | Factor 2 (common knowledge) |

| Stroke | 0.819* | 0.287 |

| Heart attack | 0.794* | 0.328 |

| Impotence | 0.816* | 0.141 |

| Premature ageing | 0.816* | 0.173 |

| Heart attack in adults (SHS) | 0.754* | 0.311 |

| Lung cancer | 0.150 | 0.839* |

| Emphysema | 0.430 | 0.639* |

| Yellow teeth | 0.250 | 0.695* |

| Lung illnesses in children (SHS) | 0.351 | 0.720* |

| Lung cancer in adults (SHS) | 0.111 | 0.711* |

| % Variance | 36.09 | 29.56 |

*p<0.05.

Figure 1.

ORs estimated from a structural equation model predicting smoking behaviour of Chinese male physicians and their smoking cessation services. ‘Uncommon knowledge’ and ‘Common knowledge’ are latent variables measured by dummy variables for awareness of hazards of smoking and secondhand smoking (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, NS, not significant).

Implementation of smoke-free hospital policy

In the survey, two questions were asked among physicians regarding the enforcement of smoke-free hospital policy: Does your hospital strictly enforce the policy among employees? and does your hospital strictly enforce the policy among patients/visitors?

Statistical analysis

A confirmatory structural equation modelling analysis was performed to test hypothesised relationships (figure 1) among the observed variables such as the smoking behaviour of peers, the latent variables such as common knowledge and uncommon knowledge of harms of smoking and passive smoking, and two key variables regarding whether physicians smoked and whether they provided any cessation services to help patients quit smoking. As its strength, structural equation modelling allows incorporation of latent variables such as health knowledge, which have major substantive importance but are measured only indirectly through multiple indicators.24 It also enables the exploration of complex relationships among variables such as how health knowledge regarding the harms of smoking may directly affect physicians’ cessation services and indirectly affect those services by affecting their own smoking. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.3., and cases with missing values were simply excluded from the analysis. We reported ORs with 95% CI, and the two-tailed significance level was set at 5% (p<0.05).

Results

Table 2 presents characteristics of the sample. Among the male physicians, 25.7% were current smokers and 15.4% smoked daily (not shown). Among all male physicians, 54% provided smoking cessation services through counselling (18.8%), distributing self-help materials (17.1%), and providing traditional remedies or medication (18.2%). Of these male physicians, 33.9% reported that they had peers who smoked in indoor areas where they worked. A high proportion of physicians were aware that smoking can cause lung cancer (95.1%), yellow teeth (95.3%), emphysema (90.7%) and that secondhand smoke can cause lung cancer in adults (92.8%) and lung illness in children (89.6%). Relatively fewer male physicians were aware that smoking can cause stroke (82.9%), heart attack (82.9%), premature ageing (80.4%) and impotence in male smokers (76.1%) and that secondhand smoke can cause heart attack in adults (80.7%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of male physicians at three Chinese cities of Changsha, Wuxi and Qingdao

| Characteristics | (N=720) (%) |

|---|---|

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 25.7 |

| No | 74.3 |

| Smoking cessation services | |

| Counselling only | 18.8 |

| Self-help material | 17.1 |

| Traditional remedies/medication | 18.2 |

| None | 46.0 |

| Age | |

| <30 | 15.6 |

| 30–39 | 45.1 |

| 40–49 | 23.2 |

| 50+ | 14.7 |

| Missing | 1.4 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 83.8 |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 12.4 |

| Missing | 3.9 |

| Education | |

| High school and below | 6.1 |

| College | 67.1 |

| Postgraduate | 23.2 |

| Missing | 3.6 |

| Peers smoking in indoor areas at the workplace | |

| Yes | 33.9 |

| No | 55.3 |

| Missing | 10.8 |

| Awareness of smoking causing the following diseases: | |

| Stroke | |

| Yes | 82.9 |

| No | 17.1 |

| Heart attack | |

| Yes | 82.9 |

| No | 17.1 |

| Lung cancer | |

| Yes | 95.1 |

| No | 4.9 |

| Emphysema | |

| Yes | 90.7 |

| No | 9.3 |

| Yellow teeth | |

| Yes | 95.3 |

| No | 4.7 |

| Impotence in males smokers | |

| Yes | 76.1 |

| No | 23.9 |

| Premature ageing | |

| Yes | 80.4 |

| No | 19.6 |

| Awareness of passive smoke causing the following diseases: | |

| Heart attack in adults | |

| Yes | 80.7 |

| No | 19.3 |

| Lung illnesses in children | |

| Yes | 89.6 |

| No | 10.4 |

| Lung cancer in adults | |

| Yes | 92.8 |

| No | 7.2 |

| Strict implementation of smoke free policies among hospital employees | |

| Yes | 69.9 |

| No | 30.1 |

| Strict implementation of smoke free policies among patients/others | |

| Yes | 48.1 |

| No | 51.9 |

| Access to cessation resources | |

| Yes | 76.7 |

| No | 23.3 |

| Received training in smoking cessation | |

| Yes | 27.6 |

| No | 72.4 |

Only 69.9% of male physicians believed that the smoke-free policy at their hospital was implemented completely among employees. Even fewer (48.1%) believed that the policy was implemented completely among patients and visitors. Of the male physicians, 76.7% reported that resources for cessation interventions, such as traditional remedies and medication, were available to help patients quit smoking. Only 27.6% reported having received training on smoking cessation approaches at conferences, symposia or workshops.

Table 3 presents the associations between smoking by male physicians and each risk factor, estimated from the structural equation modelling. Compared with their counterparts who had no uncommon knowledge, which is a latent factor measured by awareness that smoking can cause stroke, heart attack, impotence in male smokers and premature ageing and that secondhand smoke can cause heart attack, male physicians who had such uncommon knowledge were less likely to smoke (OR=0.94 95% CI 0.89 to 0.99). By contrast, common knowledge, which is a latent factor measured by physicians’ awareness that smoking can cause lung cancer, emphysema and yellow teeth and that secondhand smoke can cause lung illnesses in children and lung cancer in adults, did not predict male physicians’ smoking behaviour. In addition, male physicians were more likely to smoke if their coworkers smoked in indoor areas of their workplace (OR 1.14 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26).

Table 3.

Path coefficients estimated in a structural equation model predicting the smoking behaviour of Chinese male physicians

| Variables | Parameter estimate (b) | Standard error for b | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncommon knowledge of smoking hazards (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.062* | 0.028 | 0.94* | (0.89 to 0.99) |

| Common knowledge of smoking hazards (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.010 | 0.029 | 0.99 | (0.94 to 1.05) |

| Peer smoking (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.129* | 0.052 | 1.14* | (1.03 to 1.26) |

| Strict implementation of smoke free policy (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.016 | 0.030 | 0.98 | (0.93 to 1.04) |

| Age (Ref: 50+) | ||||

| <30 | −0.088 | 0.074 | 0.92 | (0.79 to 1.06) |

| 30–39 | −0.024 | 0.054 | 0.98 | (0.88 to 1.08) |

| 40–49 | 0.025 | 0.058 | 1.02 | (0.91 to 1.15) |

| Marital status (Ref: Single/divorced/widowed) | ||||

| Married | 0.075 | 0.064 | 1.08 | (0.95 to 1.22) |

| Education (Ref: High school and below) | ||||

| College | −0.006 | 0.081 | 0.99 | (0.85 to 1.16) |

| Postgraduate | 0.004 | 0.086 | 1.00 | (0.85 to 1.19) |

*p<0.05.

Table 4 presents the associations between physicians’ cessation services and each risk factor, estimated from the structural equation modelling. Physicians who had uncommon knowledge were more likely (OR 1.05 95% CI 1.01 to 1.10) to provide cessations services than physicians who had no such knowledge; physicians who were current smokers were less likely (OR 0.87 95% CI 0.81 to 0.93) to do so than physicians who did not smoke; and physicians whose peers smoked in indoor areas of their workplace were less likely (OR 0.82 95% CI 0.76 to 0.89) to provide cessation services than physicians whose peers did not smoke at their workplace. In addition, access to cessation resources predicted a higher likelihood (OR 1.69 95% CI 1.58 to 1.82) of providing cessation services among male physicians as did training in smoking cessation at special conferences, symposia or workshops (OR 1.36 95% CI 1.27 to 1.45).

Table 4.

Path coefficients estimated in a structural equation model predicting the smoking cessation services provided by Chinese male physicians

| Variables | Parameter estimate (b) | Standard error for b | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.142** | 0.033 | 0.87** | (0.81 to 0.93) |

| Access to cessation resources (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.527** | 0.037 | 1.69** | (1.58 to 1.82) |

| Training in smoking cessation (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.304** | 0.033 | 1.36** | (1.27 to 1.45) |

| Uncommon knowledge of smoking hazards (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.053* | 0.024 | 1.05* | (1.01 to 1.10) |

| Common knowledge of smoking hazards (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.004 | 0.024 | 1.00 | (0.96 to 1.05) |

| Peer smoking (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.196** | 0.043 | 0.82** | (0.76 to 0.89) |

| Strict implementation of smoke free policy (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | −0.025 | 0.025 | 0.98 | (0.93 to 1.02) |

| Age (Ref: 50+) | ||||

| <30 | −0.046 | 0.061 | 0.96 | (0.85 to 1.08) |

| 30–39 | −0.028 | 0.045 | 0.97 | (0.89 to 1.06) |

| 40–49 | −0.087 | 0.048 | 0.92 | (0.83 to 1.01) |

| Marital status (Ref: Single/divorced/widowed) | ||||

| Married | 0.025 | 0.053 | 1.03 | (0.92 to 1.14) |

| Education (Ref: High school and below) | ||||

| College | −0.044 | 0.067 | 0.96 | (0.84 to 1.09) |

| Postgraduate | −0.028 | 0.072 | 0.97 | (0.84 to 1.12) |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Figure 1 presents all the associations between risk factors and the two key variables: smoking behaviours of physicians and their smoking cessation services. As shown, some risk factors, such as uncommon knowledge of harms of smoking and the presence of smoking peers, had a direct effect on physicians’ cessation services, as presented in table 4 and discussed above, and exhibited an indirect effect on the cessation services by the path between these risk factors and physicians’ smoking behaviours and then by the path between physicians’ smoking behaviours and their cessation services.

Discussion

We found that the prevalence of smoking among Chinese male physicians in Qingdao, Changsha and Wuxi was 25.7%. This rate is substantially higher than that of US health professionals (<6%)25 but lower than most rates reported in previous studies, such as the prevalence of 41% found in a study of male physicians in six Chinese cities: Chengdu, Guangzhou, Harbin, Lanzhou, Tianjin and Wuhan.6 The differentials may reflect regional differences in smoking prevalence and different sampling methods. It was found that large provincial or city hospitals have a significantly lower prevalence of smoking compared with lower-level hospitals such as community health centres in China.2 Although the possibility cannot be excluded that smoking rate among physicians has declined since the Chinese Ministry of Health enacted the nationwide smoke-free hospital policy, our study suggests that such policy is not strictly implemented among hospital employees and among patients and visitors in particular.

Our study suggests that although the majority of male physicians believed that smoking may cause diseases such as lung cancer, many of them were not fully aware of the harm of cigarette smoking. For example, in our sample, only 82.9% of male physicians believed that smoking can cause stroke and heart attack, and only 76.1% believed that smoking can cause impotence in male smokers. Similarly, a previous study showed that only two-thirds of physicians in China believed that smoking could cause ischaemic heart disease, and only 21% of physicians believed that secondhand smoking was a cause of sudden infant death syndrome.6 It is obvious that the awareness of dangers of tobacco is still insufficient among Chinese physicians. By contrast, our study suggests that the awareness of harm of smoking may significantly prevent physicians from smoking because physicians who possessed the uncommon knowledge that smoking and passive smoking may cause stroke and heart attack, premature ageing, and impotence in male smokers were less likely to smoke. Evidence from studies in other countries also suggests the importance of scientific knowledge regarding opposition to smoking among physicians.26 In the USA, the prevalence of smoking among physicians was as high as that in the general population after World War I, reaching its peak of 40% in 1959.10 However, the prevalence among physicians has declined since 1974 at an annual rate of 1.15% on average,27 reaching below 10% by the mid-1990 s.28 What preceded the decline was the increase in awareness of the dangers of tobacco and in scientific knowledge among physicians as well as powerful peer non-smoking norms.10 27

Our study also suggests that increasing the awareness and knowledge of the hazards of smoking can curb smoking among physicians themselves and may increase their provision of smoking cessation services through direct and indirect paths as shown in the structural equation modelling diagram (figure 1). Specifically, physicians who had uncommon knowledge regarding health consequences, such as stroke and heart attack, premature ageing and impotence in male smokers, were more likely to provide cessation services to help patients quit smoking (OR 1.11 95% CI 1.01 to 1.23). In addition, our findings also suggest that such uncommon knowledge of physicians may have indirect impact on their cessations services because the physicians with uncommon knowledge are less likely to smoke (OR 0.88 95% CI 0.83 to 0.93) and the physicians who do not smoke themselves are more likely to provide cessation services (OR 1.11 95% CI 1.01 to 1.23). Our findings are consistent with numerous previous studies. For example, it was found that non-smoking physicians are more likely to ask about patients’ smoking status, advise smokers to quit and provide encouragement when giving advice about quitting.6 29 30 In an environment where smoking is the norm among physicians, it is unconvincing for them to persuade smoking patients to quit, and improbable that they would be motivated to do so.11

Given the accumulated evidence and our own finding that Chinese physicians lack strong awareness and knowledge about the harms of active and passive smoking and given that a paucity of such knowledge may promote their own smoking behaviour and hamper their provision of cessation services, the need to address this issue in the medical community is urgent. Educating physicians about the nature and the scope of the danger of tobacco use as well as promoting cessation among physicians first will hopefully improve the health of the physicians and equip them to better address the smoking behaviours of their patients.26 27 31

To maximise the provision of cessation services by physicians, providing training and resources for cessation services are crucial in addition to improving their awareness of the hazards of smoking. Training has been found effective in increasing medical students’ confidence in their ability to provide smoking cessation assistance.32 Physicians who received comprehensive training from the Thai Pharmacy Network for Tobacco Control were significantly more likely to provide brief advice on smoking cessation, compared with those without training, resulting in the suggestion that integrating similar training programmes into medical school curricula may better prepare new physicians on smoking cessation consultation.33

Admittedly, to create smoke-free medical facilities, China faces many social and cultural challenges. For example, smoking is especially difficult to address because of the tradition of offering cigarettes as a social courtesy and a sign of respect; physicians who receive cigarettes as gifts are more likely to remain reluctant to educate their patients about the dangers of tobacco use or to help them quit smoking.4 However, China is not unique in facing such cultural barriers. Smoking was a widely accepted and ingrained practice in the USA,10 where many physicians quit smoking for the same reasons as the general population, including concern for health.27 Antismoking and smoking cessation initiatives have often been effective in reducing morbidity in other countries despite certain cultural differences,26 suggesting the possibility of modifying such approaches in a culturally feasible manner in China.

Finally, the limitations of this study should be addressed. First, our findings are based on data from hospitals in three cities, not a national representative sample of physicians. Second, the smoking behaviour and provision of smoking cessation services were self-reported, which may be subject to underestimation of smoking prevalence and overestimation of provision of smoking-cessation services.34 35 Moreover, given the nature of a cross-sectional design of the study, any attempt at causal interpretation should be made with caution.

Key messages.

This study found that smoke-free policy is not consistently implemented or enforced and healthcare facilities have not yet been established as smoke-free on a national scale.

Although a majority of Chinese male physicians believed that smoking may cause diseases such as lung cancer, many of them were not fully aware of the range of harms caused by cigarette smoking.

Increasing the awareness of the hazards of smoking among Chinese physicians, in particular health consequences that are less commonly known, such as an increased risk of stroke and heart attack, premature aging, and impotence in male smokers, would potentially curb smoking among physicians themselves and also increase their provision of smoking cessation services.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The author name ‘Michael Erikson’ has been corrected to ‘Michael Eriksen’.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Yao Shi for her excellent research assistance.

Contributors: CH designed the study and drafted the manuscript. CG analysed and interpreted the data. CG, SY, YF, JS, ME, PR and JK helped draft the manuscript and revised it critically.

Funding: This work was partially supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number 51437). The funding sources had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was cleared for ethics by the Institutional Review Boards or Research Ethics Boards of Qingdao CDC (China), Changsha CDC (China), Wuxi CDC (China) and Emory University (USA).

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2469–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah AS, Qiming F, Pun V, et al. A review of tobacco smoking and smoking cessation practices among physicians in China: 1987–2010. Tob Control 2013;22:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu BQ, Peto R, Chen ZM, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 1. Retrospective proportional mortality study of one million deaths. BMJ 1998;317:1411–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan J, Xiao S, Ouyang D, et al. Smoking behavior, knowledge, attitudes and practice among health care providers in Changsha city, China. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:737–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman T. ABC of smoking cessation. Use of simple advice and behavioural support. BMJ 2004;328:397–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Y, Ong MK, Tong EK, et al. Chinese physicians and their smoking knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:15–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder SA. What to do with a patient who smokes. JAMA 2005;294:482–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff, and Consortium Representatives A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence—A US Public Health Service report. JAMA 2000;283:3244–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Tobacco Free Initiative. The role of health professionals in tobacco control 2005. http://www1.paho.org/english/ad/sde/ra/bookletWNTD05.pdf (accessed 2 May 2013)

- 10.Smith DR, Leggat PA. The historical decline of tobacco smoking among Australian physicians: 1964–1997. Tob Induc Dis 2008;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meshefedjian GA, Gervais A, Tremblay M, et al. Physician smoking status may influence cessation counseling practices. Can J Public Health 2010;101:290–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pipe A, Sorensen M, Reid R. Physician smoking status, attitudes toward smoking, and cessation advice to patients: An international survey. Patient Educ Couns 2009;74:118–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garfinkel L. Cigarette smoking among physicians and other health professionals, 1959–1972. CA Cancer J Clin 1976;26:373–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li HZ, Fish D, Zhou X. Increase in cigarette smoking and decline of anti-smoking counselling among Chinese physicians: 1987–1996. Health Promot Int 1999;14:123–31 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DR, Zhao I, Wang L. Tobacco smoking among doctors in mainland China: a study from Shandong province and review of the literature. Tob Induc Dis 2012;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Health Department of the General Logistics Department of the People's Liberation Army, Logistics Department of the Armed Police Forces. 2009. Decision to ban smoking completely in the medical and health system by 2011. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-05/22/content_1321944.htm (accessed 2 May 2013)

- 17.Ministry of Health General Office, Department of Maternal and Child Health Care & Community Health. 2009. Implementation plan for local tobacco control projects supported with central government funding. http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2009-12/25/content_1496799.htm (accessed 2 May 2013)

- 18.Lin Y, Fraser T. A review of smoke-free health care in mainland China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:453–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fee E, Brown TM. Hospital smoking bans and their impact. Am J Public Health 2004;94:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo DR, Brownson RC, Johnson JC, et al. Hospital smoking bans and employee smoking behavior: results of a national survey. JAMA 1996;275:1252–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang C, Liu J, Li C, et al. Smoking susceptibility and its predictors among adolescents in China: evidence from Ningbo City. J Addict Res Ther 2012;S8:004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang GH, Li Q, Wang CX, et al. Findings from 2010 Global Adult Tobacco Survey: implementation of MPOWER policy in China. Biomed Environ Sci 2010;23:422–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Cowling DW, Tang H. The impact of social norm change strategies on smokers’ quitting behaviours. Tob Control 2010;19 (suppl_uppl 1 China Tobacco Control Research Symposium):i51–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthen BO. Beyong sem: General latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika 2002;29:81–117 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong EK, Strouse R, Hall J, et al. National survey of U.S. health professionals’ smoking prevalence, cessation practices, and beliefs. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:724–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossman DW, Knox JJ, Nash C, et al. Smoking: attitudes of Costa Rican physicians and opportunities for intervention. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:315–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson DE, Giovino GA, Emont SL, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking among US physicians and nurses. JAMA 1994;271:1273–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DR, Leggat PA. An international review of tobacco smoking in the medical profession: 1974–2004. BMC Public Health 2007;7:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank E, Rothenberg R, Lewis C, et al. Correlates of physicians’ prevention-related practices. Findings from the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:359–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam TH, Jiang CQ, Chan YF, et al. Smoking cessation intervention practices in Chinese physicians: do gender and smoking status matter? Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:126–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnoya J, Glantz S. Knowledge and use of tobacco among Guatemalan physicians. Cancer Causes Control 2002;13:879–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen SS, Bland CJ, Dawson SJ. A mini-workshop to train medical students to use a patient-centered approach to smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med 1990;6:28–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimpitakpong P, Chaiyakunapruk N, Dhippayom T. A national survey of training and smoking cessation services provided in community pharmacies in Thailand. J Community Health 2010;35:554–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perezstable EJ, Benowitz NL, Marin G. Is serum cotinine a better measure of cigarette-smoking than self-report. Prev med 1995;24:171–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Stafford RS, et al. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA 1998;279:604–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]