Abstract

The N-(E)-fluorobutenyl-3β-(para-halo-phenyl)nortropanes 9-12 were synthesized as ligands of the dopamine transporter (DAT) for use as 18F-labeled positron emission tomography (PET) imaging agents. In vitro competition binding assays demonstrated that compounds 9-12 have a high affinity for the DAT and are selective for the DAT compared to the serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. MicroPET imaging with [18F]9-[18F]11 in anesthetized cynomolgus monkeys showed high uptake in the putamen with lesser uptake in the caudate, but significant washout of the radiotracer was only observed for [18F]9. PET imaging with [18F]9 in an awake rhesus monkey showed high and nearly equal uptake in both the putamen and caudate with peak uptake achieved after 20 min followed by a leveling-off for about 10 min and then a steady washout and attainment of a quasi-equilibrium. During the time period 40-80 min post-injection of [18F]9 the ratio of uptake in the putamen and caudate vs. cerebellum uptake was ≥ 4.

Introduction

The human dopamine transporter (DAT)a is a 620-amino acid transmembrane protein which belongs to the family of Na+/Cl- dependent transporters.3, 4 In the central nervous system (CNS) the DAT is located on presynaptic neurons and functions to remove the neurotransmitter dopamine from the synapse thereby terminating the signaling action of dopamine.5, 6 The DAT is found in high densities in certain brain regions which include the putamen, caudate, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle whereas lower densities are found in the substantia nigra, amygdala, and hypothalamus.7, 8 Several neuropsychiatric disorders have been associated with the DAT including Parkinson's Disease (PD),9-11 attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),12 supranuclear palsy,10 and Tourette's Syndrome.13 The ability to image the DAT with positron emission tomography (PET) may aid in the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of these diseases by providing a means to study the DAT in vivo and by allowing for the in vivo measurement of DAT density in specific brain regions.14 Furthermore, a suitable DAT PET tracer can be used to measure the occupancy of DAT therapeutics15 and may facilitate the development of new DAT therapeutics.16

The DAT is also the target of several drugs of abuse including cocaine,17, 18 amphetamines, and MDMA (ecstasy) and this has led to the search for compounds that can be employed as potential cocaine addiction therapeutics.19, 20 From this research evolved the 3β-phenyl tropane class of DAT ligands of which compounds 1-6 were the first to be prepared.21-24 These compounds have since been exploited for PET imaging due to the ability to radiolabel with carbon-11 on either the N-methyl group or the O-methyl ester.25-28 Carbon-11 has a half-life of 20.4 min which limits the use of 11C-labeled tracers to the location where they are prepared and to imaging sessions of about 2 h. Fluorine-18 has a half-life of 109.8 min which allows for longer radiosynthesis times and imaging sessions, and also for the transport of the 18F radiotracer to PET imaging facilities that do not have onsite cyclotrons. Additionally, 18F positrons have a lower maximum energy (0.64 MeV)29 than 11C positrons (0.97 MeV) which therefore deposits less energy into tissue and also results in a positron with a shorter linear range which allows for higher spatial resolution.30, 31 These physical properties of 18F are serendipitous due to the increasingly valuable role that 19F is playing in medicinal chemistry32-35 and a variety of synthetic methods have now been developed to incorporate 18F or 19F into molecules.36-38

Out of compounds 1-6 only compound 2 has the potential to be radiolabeled with 18F. Thus, [18F]2 was prepared and evaluated in rats39 and humans.40 In humans the peak uptake of [18F]2 in the putamen and caudate occurred at 225 min followed by a slow washout. Although [18F]2 showed high uptake in the striatum and the aryl-fluorine bond was found to be metabolically stable to defluorination, the time to peak uptake was considered to take too long and so [18F]2 was not an optimal DAT PET tracer. Numerous other fluorinated derivatives of 1-6 which contain the 18F-radiolabel as an N-fluoroalkyl group or an O-fluoroalkyl ester have also been prepared and evaluated.41 Among the numerous derivatives reported, compounds 7 (FECNT)42 and 8 (FPCIT)43 emerged as viable DAT PET tracers and have found use in human PET imaging. 44-50 Both compounds [18F]7 and [18F]8 achieve a high uptake and specific binding in the putamen and caudate but neither compound washes out significantly during the course of the study which is needed to enable kinetic modeling of the tracer behavior.51, 52 Compound 8 also has a higher binding affinity at the serotonin transporter (SERT) than the DAT53 and so [18F]8 is not a DAT-specific PET tracer. Additionally, [18F]8 defluorinates, which is similar to other tracers containing an [18F]fluoropropyl group,54-56 whereas [18F]7 is metabolized to a polar radiometabolite57 which can cross the blood-brain barrier (a similar result was recently reported for the amyloid imaging agent [18F]FDDNP58). Thus, further improvements are still needed in order to obtain a DAT-selective 18F-labeled PET tracer that can achieve peak uptake, binding equilibrium, and washout in a relatively short period of time while also not defluorinating or producing radiolabeled metabolites that can cross the blood-brain barrier.

We have previously reported the N-(E)-fluorobutenyl compounds 9-12 along with preliminary in vitro binding data and rat biodistribution data.59, 60 The rationale for the N-(E)-fluorobutenyl group was based upon the characterization and imaging properties of the iodine-123 DAT imaging agent N-((E)-3-[123,125I]iodopropen-1-yl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)nortropane (MMG-142E/IPT)61 which showed nanomolar DAT affinity and high striatal to cerebellar ratios with relatively fast washout kinetics, indicating reversible binding, in non-human and human primates.62, 63 We hypothesized that the N-(E)-4-[18F]fluorobut-2-en-1-yl group would serve as a bioisostere for the N-(E)-3-[123, 125I]iodopropen-1-yl group for a new class of DAT PET imaging agents. The preliminary binding data of compounds 9-12 demonstrated that the (E)-configuration of the fluorobutenyl group was the more biologically active configuration and also that halosubstitution of the phenyl ring resulted in higher binding affinity at the DAT when compared to the unsubstituted phenyl group. Subsequently, the para-methyl analog 13 was reported64 and, recently, several related derivatives have been reported.65, 66 Herein we report the synthesis and binding affinity determination of 9-12 (along with 13 for comparison) in conjunction with the microPET imaging of [18F]9-[18F]11 and [18F]13 in anesthetized cynomolgus monkeys and the high resolution research tomograph (HRRT) imaging of [18F]9 in an awake rhesus monkey.67

Chemistry

The N-(E)-fluorobutenyl nortropanes 9-13 were synthesized by reacting the appropriate nortropane24, 25, 68 with (E)-4-fluoro-1-tosyloxy-2-butene (14) (Scheme 1). Compound 14 was prepared from trans-1,4-dibromo-2-butene (15) as shown in Scheme 1. Reaction of 15 with KOAc in AcOH according to the literature procedure69, 70 afforded the diacetoxy compound 16 which was purified on silica rather than by the traditional distillation method. Acid-catalyzed ethanolysis of 16 afforded the diol 17 in nearly quantitative yield. Thus, this method provides a simplified synthesis of diol 17 which avoids the previously reported LAH reduction of 2-butyne-1,4-diol71 or DIBAL reduction of a dialkyl fumarate.72, 73 Diol 17 was reacted with tosyl chloride to give ditosylate 18 which was then reacted with tetrabutylammonium fluoride to give 14.

Scheme 1.

Radiochemistry

Compound [18F]14 was obtained by reacting 18 with K18F/Kryptofix-222 complex in CH3CN. Following preparation of [18F]14, a DMF-solution of the appropriate nortropane24, 25, 68, 74 was added, the mixture was heated at 105 °C for 15 min, and then purified by semi-preparative HPLC. The desired HPLC fractions were combined and diluted with H2O, and the product was then isolated from this solvent mixture by solidphase extraction according to a previously reported procedure.75 The radiotracer was then formulated as a 10% EtOH/saline solution. The octanol/water partition coefficients76, 77 of [18F]9-[18F]11 were measured according to a previously reported procedure78, 79 and the results are shown in Table 1. These values are all in the range of log P = 1-3 which allows for passive diffusion of the radiotracer across the blood-brain barrier. As expected, the lipophilicity of each radiotracer increases with increasing lipophilicity of the halogen substituent.

Table 1.

Octanol/Water Partition Coefficients.

| compound | log P7.4a | n |

|---|---|---|

| [18F]9 | 1.95 ± 0.01 | 8 |

| [18F]10 | 2.21 ± 0.02 | 7 |

| [18F]11 | 2.33 ± 0.03 | 8 |

Average value of n determinations ± the standard deviation.

In Vitro Competition Binding Assays

The binding affinities of 2 and the N-(E)-fluorobutenyl nortropanes 9-13 to human monoamine transporters (Table 2) were determined using in vitro competition binding assays with membranes prepared from cells transfected with the human SERT, DAT, or norepinephrine transporter (NET) according to our previously reported procedure.80, 81 Compounds 2 and 9-13 were screened as the free bases whereas salts were used for the control compounds: cocaine•HCl (DAT), (S)-citalopram•oxalate82 (SERT), and desipramine•HCl83 (NET). The competing ligands employed were [3H](R,S)-citalopram•HBr84 (SERT), [125I]RTI-5523 ([125I]5, DAT), or [3H]nisoxetine85 (NET).

Table 2.

Results of In Vitro Competition Binding Assays with Transfected Human Monoamine Transporters.

| compd | Ki (nM)a | DAT selectivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| hDAT | hSERT | hNET | SERT/DAT | NET/DAT | |

| 9 | 9.5 ± 2.6d | 357.4 ± 193.0g | 2607 ± 1432d | ∼ 38 | ∼ 274 |

| 10 | 0.6 ± 0.3c | 11.3 ± 6.4h | 142 ± 30e | ∼ 19 | ∼ 237 |

| 11 | 0.4 ± 0.0c | 8.5 ± 0.8d | 87 ± 8 | ∼ 21 | ∼ 218 |

| 12 | 0.5 ± 0.2c | 2.2 ± 1.1d | 145 ± 125d | ∼ 4 | ∼ 290 |

| 13 | 2.7 ± 0.1c | 147.0 ± 79.3i | 265 ± 146e | ∼ 54 | ∼ 98 |

| 2 | 10.6 ± 0.8b | N/D | N/D | N/A | N/A |

| Cocaine•HCl | 46.3 ± 13.5c | N/D | N/D | N/A | N/A |

| (S)-Citalopram•oxalate | N/D | 1.0 ± 0.6 | N/D | N/A | N/A |

| Desipramine•HCl | N/D | N/D | 0.8 ± 0.7b | N/A | N/A |

Geometric mean of n determinations ± the standard deviation (each determination performed in triplicate).

n = 2.

n = 3.

n = 4.

n = 5.

n = 6.

n = 7.

n = 8.

n = 9.

N/A = Not applicable.

N/D = Not determined.

Compound 12, which is the N-(E)-fluorobutenyl analog of 5 (RTI-55/β-CIT), has a high affinity for the DAT as well as for the SERT and thus displays only a four-fold selectivity for the DAT over the SERT (this lack of selectivity is very similar to that of 553, 86). Compounds 10 and 11 also have a high DAT affinity and display about a 20-fold selectivity over the SERT. This high DAT affinity and moderate SERT affinity is also similar to the N-methyl analogs 3 (RTI-31) and 4 (RTI-51), respectively.87 Compound 13 has a DAT affinity similar to the N-methyl analog 6 (RTI-32)87 and is about 54-times more selective for the DAT over the SERT. Compound 9 has a reduced DAT affinity relative to compounds 10-13 but the affinity is very similar to the N-methyl analog 2 (the binding affinity determined for 2 is in close agreement with other reported values22, 25, 88) indicating that replacement of the N-methyl group with an N-(E)-fluorobutenyl group does not significantly alter DAT binding. Compound 9 is also more selective for the DAT over the SERT than the other halo-substituted compounds 10-12. All of the N-(E)-fluorobutenyl tropanes tested have a high DAT vs. NET selectivity with the halo-substituted compounds 9-12 displaying a selectivity more than twice that of the methyl-substituted compound 13.

In Vivo Nonhuman Primate PET Imaging

MicroPET imaging was performed in anesthetized cynomolgus monkeys using a Concorde microPET P4 according to our previously reported procedure.80 The microPET images for a 145-minute baseline study with [18F]9 are shown in Figure 1 and the time-activity curves (TACs) are shown in Figure 2. As shown by Figures 1 and 2, high uptake of radioactivity is observed in the regions of the brain known to have high DAT density.7, 8 Rapid uptake of [18F]9 into the putamen is observed (Figure 2) with peak uptake achieved within 20 min followed by a steady washout. Uptake of [18F]9 in the caudate is less than that observed in the putamen along with a slower rate of uptake and a minimal washout during the first 75 min of the study. Uptake of [18F]9 in the substantia nigra is rapid with peak uptake achieved within 10 min followed by a steady washout. Uptake in the cerebellum is rapid followed by a rapid washout with little or no retention of the tracer as expected for a brain region devoid of DAT. A small amount of radioactivity is also observed in the skull (Figure 1) indicating a low degree of defluorination. This is not surprising since the 18F-radiolabel is in an allylic position and it has been previously reported that 18F-benzyl fluorides can also undergo defluorination.89, 90 In order to demonstrate that the uptake of [18F]9 observed in the baseline study is a result of preferential binding to the DAT, a chase study was performed with the DAT ligand RTI-113•HCl87, 91, 9219. As shown in Figure 3, administration of 19 (0.3 mg/kg) at 90 min post-injection results in a complete displacement of [18F]9 thus indicating that the observed uptake was a result of binding to the DAT.

Figure 1.

MicroPET images (summed 0-145 min) obtained by injection of [18F]9 into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey.

Figure 2.

MicroPET baseline TACs obtained by injection of [18F]9 into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey.

Figure 3.

MicroPET TACs showing the result of injection of 19 (0.3 mg/kg) into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey at 90 min post-injection of [18F]9.

MicroPET baseline studies were also performed with [18F]10, [18F]11, and [18F]13 (Figures 4-6, respectively). All three tracers show high uptake in the putamen followed by minor washout during the course of the 235-min study. The initial uptake into the putamen is rapid with peak uptake achieved within 30 min for [18F]10 and [18F]11, and within 55 min for [18F]13. Uptake in the caudate is less than that observed in the putamen for [18F]10, [18F]11, and [18F]13 and the rate of uptake is also slower. Furthermore, the uptake in the caudate fails to wash out during the entire course of the study for [18F]10, [18F]11, and [18F]13. The different levels of uptake of [18F]13 in the putamen and caudate and the lack of washout are very similar to the results previously reported for [11C]13 in an anesthetized baboon.64

Figure 4.

MicroPET baseline TACs obtained by injection of [18F]10 into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey.

Figure 6.

MicroPET baseline TACs obtained by injection of [18F]13 into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey.

It has been demonstrated in numerous instances that anesthesia can affect the behavior of PET tracers.93-98 Therefore, an 85-min PET study was performed on a high resolution research tomograph (HRRT) with [18F]9 in an awake rhesus monkey to determine whether there is a difference between the behavior of [18F]9 in awake and anesthetized states (Figures 7 and 8). As shown in Figure 8, the uptake of [18F]9 is nearly equal in the putamen and caudate in each hemisphere of the awake rhesus monkey brain. This suggests that the different levels of uptake between the putamen and caudate observed in the anesthetized monkey microPET studies shown in Figures 2-6 is due to anesthesia effects. The rate of uptake of [18F]9 into the putamen and caudate of the awake rhesus monkey is fast with peak uptake achieved after about 20 min followed by a leveling-off for a period of about 10 min and then a slow but steady washout during which time a quasi-equilibrium14 is achieved. The kinetic behavior of [18F]9 in the putamen and caudate of the awake monkey is very similar to the kinetic behavior in the putamen of the anesthetized monkey suggesting that the overall kinetics of [18F]9 in the putamen are not significantly altered by anesthesia whereas the different degree of uptake and lack of washout from the caudate in the anesthetized monkey may be the result of anesthesia. Based on these results, it is believed that the rate of washout from the putamen for [18F]10, [18F]11, and [18F]13 observed in the anesthetized monkey microPET studies would not change significantly in an awake state.

Figure 7.

HRRT PET images (summed 55-75 min) obtained by injection of [18F]9 into an awake rhesus monkey.

Figure 8.

HRRT baseline TACs obtained by injection of [18F]9 into an awake rhesus monkey.

The difference in the rate of washout between [18F]9-[18F]11 and [18F]13, aside from any anesthesia effects, is believed to be the result of the different binding affinities shown in Table 2. The DAT is found in high density in the caudate and putamen and, therefore, a very high-affinity ligand is not needed to image the DAT.99 Compounds 10 and 11 have a sub-nanomolar affinity for the DAT and compound 13 has an affinity of 2.7 nM, whereas 9 has an affinity of about 9.5 nM. The lower affinity compound [18F]9 is able to bind to the DAT, then dissociate and washout whereas the higher affinity compounds have a delayed washout due to stronger and/or prolonged binding to the DAT in combination with the high density of available binding sites.

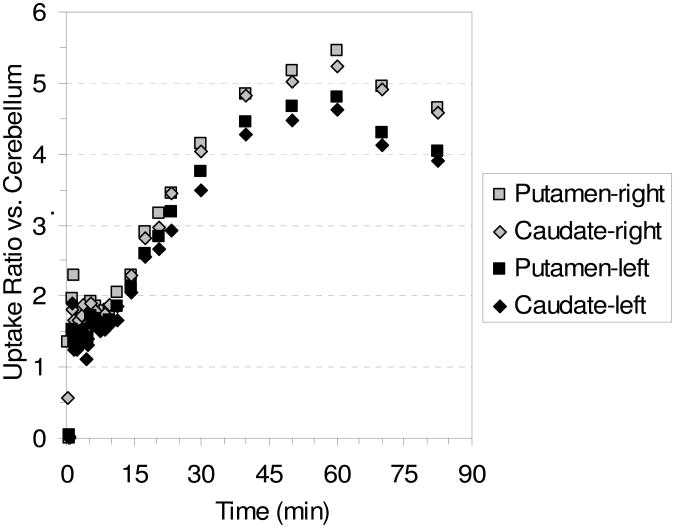

Table 3 shows the ratio of uptake in the putamen and caudate vs. cerebellum uptake in the awake study with [18F]9 and the uptake ratios are plotted vs. time in Figure 9. From Table 3 and Figure 9 it can be seen that the highest uptake ratios are obtained after 60 min post-injection and that ratios of ≥ 4 are maintained for the period 40-80 min post-injection. From the HRRT PET images in Figure 7 it can be seen that the uptake of [18F]9 is in agreement with the known distribution of DAT in the brain. But, just as was seen with the microPET images in Figure 1, visualization of the skull indicates some degree of defluorination. Compound [18F]9, therefore, displays many of the desired properties of an 18F-labeled DAT PET tracer including selectivity for the DAT over the SERT and NET, and the achievement of peak uptake and binding equilibrium in a short time frame followed by a steady washout. Unfortunately, a minor degree of defluorination at the allylic position occurs. But, it may be possible to block this defluorination by the administration of disulfiram which has already been proven to inhibit defluorination of [18F]FCWAY.100

Table 3.

Ratio of Uptake of [18F]9 in the Caudate and Putamen vs. Cerebellum Uptake at Selected Time Points for the HRRT Awake Rhesus Monkey Study Shown in Figure 7.

| Time (min) | Putamen (left) | Caudate (left) | Putamen (right) | Caudate (right) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 4.0 |

| 40 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| 50 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 5.0 |

| 60 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| 70 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

| 82.5 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

Figure 9.

Graph of the ratio of uptake of [18F]9 in the caudate and putamen vs. cerebellum uptake with time for the HRRT awake rhesus monkey study shown in Figure 8.

Summary

The N-(E)-fluorobutenyl-3β-(para-halo/methyl-phenyl)nortropanes 9-13 were synthesized by reacting the respective nortropane with 14, which was synthesized in 4 steps from 15. In vitro competition binding assays demonstrated that 9-13 have binding affinities and selectivities similar to their N-methyl analogs and that the chloro-, bromo-, and iodo-derivatives 10-12, respectively, bind to the DAT with a 15-fold or greater affinity than the fluoro-derivative 9. MicroPET imaging in anesthetized cynomolgus monkeys with [18F]9-[18F]11 and [18F]13 demonstrated that this very high binding affinity of the chloro-, bromo-, and methyl-derivatives prevented the radiotracer from significantly washing out of the DAT-rich brain regions during the course of the study. This apparent irreversible binding is believed to result from the combination of high DAT affinity of the radiotracer and high DAT density in the putamen and caudate. The lower affinity radiotracer [18F]9 achieved rapid peak uptake in the putamen followed by a steady washout whereas uptake in the caudate barely washed out during the course of the study. HRRT PET imaging with [18F]9 in an awake rhesus monkey showed rapid and high uptake in both the putamen and caudate with peak uptake achieved after 20 min post-injection followed by a steady washout from both the putamen and caudate thus indicating that the lack of washout in the microPET study was most likely due to an anesthesia effect. Uptake ratios of ≥ 4 were obtained in the putamen and caudate during the period 40-80 min post-injection of [18F]9 in the awake study. Thus, in an awake state, [18F]9 is able to achieve rapid peak uptake in the putamen and caudate with high uptake ratios relative to cerebellum uptake. A minor drawback of the [18F]-fluorobutenyl group is that some degree of defluorination is observed but it may be possible to prevent this defluorination by administering disulfiram prior to the imaging session.

Experimental Section

General

Trans-1,4-dibromo-2-butene (15) was purchased from both Acrös and Aldrich. Crystallization of tropanes was performed by stirring a refluxing hexanes solution of the tropane for 10 min, decanting the hot solution into a pre-heated 25-mL Erlenmeyer flask, capping the flask with a rubber septum, and storing the flask in a freezer (-15 °C). NMR spectra were obtained on Varian Unity and Mercury spectrometers at the specified frequencies. 1H chemical shifts are referenced to internal TMS or residual CHCl3 (7.26 ppm) and 13C chemical shifts are referenced to CDCl3 (77.23 ppm). Silica gel used was EMD Silica Gel 60, 40-63 μm. Vacuum flash chromatography was performed by placing silica in a medium-fritted filter (31 cm length × 4 cm i.d. – Kontes Glassware #956250-0044 with adapter #205000-2440), eluting under vacuum, and collecting fractions in 125-mL flat-bottomed boiling flasks. Radial chromatography was performed with a Harrison Research Chromatotron. Semipreparative HPLC: Waters XTerra Prep RP18, 5 μm, 19 × 100 mm + guard cartridge (19 × 18 10 mm), 60:40:0.1 v/v/v MeOH/H2O/NEt3. Analytical HPLC: Waters NovaPak 3.9 × 150 mm, 75:25:0.1 v/v/v MeOH/H2O/NEt3. HRMS was performed by the Emory University Mass Spectrometry Center. Compound purity was determined by elemental analysis and was found to be >95%. Elemental analysis was performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. (www.atlanticmicrolab.com).

N-((E)-4-fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-fluorophenyl)nortropane (9)

Nor-β-CFT25 (145 mg, 0.55 mmol), 14 (129 mg, 0.53 mmol), i-Pr2NEt (0.12 mL, 0.69 mmol), and CHCl3 (25 mL) were stirred at reflux under Ar(g) for 17 h and then cooled to room temperature. The solution was poured onto dry silica (43 mm h × 43 mmi.d.) and eluted under vacuum: CH2Cl2 (25 mL), hexanes (50 mL), hexanes/EtOAc/Net3 v/v/v 90:8:2 (50 mL), 75:20:5 (200 mL). The desired fractions were combined and the solvent was removed to give a yellow syrup that was further purified by radial chromatography (2 mm silica, 98:1:1 v/v/v hexanes/EtOAc/NEt3 (300 mL)) to afford a colorless syrup (152 mg). Crystallization from refluxing hexanes (3 mL) afforded white crystals (122 mg, 66%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.22 (dd, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 5.4 Hz), 6.95 (apparent t, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.78 (m, 2 H), 4.83 (dd, 2 H, JHF = 47.4 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.66 (partially resolved dd, 1 H, J = 3.3 Hz, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.50 (s, 3 H), 3.43 (m, 1 H), 3.02 (m, 1 H + 1 H overlapping resonances), 2.88 (m, 1 H + 1 H overlapping resonances), 2.60 (td, 1 H, J = 12.8 Hz, J = 2.6 Hz), 2.10 (m, 1 H), 2.01 (m, 1 H), 1.75 (m, 1 H), 1.66 (m, 2 H); 13C/APT (even +, odd -) NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.07 (+), 161.30 (+, d, 1Jcf = 243.6 Hz), 138.75 (+, d, 4Jcf = 3.2 Hz), 134.36 (-, d, J = 11.8 Hz), 129.00 (-, d, 3Jcf = 7.7 Hz), 126.45 (-, d, J = 16.6 Hz), 114.85 (-, d, 2Jcf = 20.9 Hz), 83.36 (+, d, 1Jcf = 161.5 Hz), 62.47 (-), 61.46 (-), 55.09 (+, d, 4Jcf = 1.4 Hz), 52.99 (-), 51.21 (-), 34.41 (+), 33.86 (-), 26.24 (+), 26.07 (+); HRMS (APCI) [MH]+ Calcd for C19H24O2NF2: 336.1770, found: 336.1769; semi-preparative HPLC: tR = 18.9 min (9 mL/min); analytical HPLC: tR = 3.9 min (0.95 mL/min); Anal. Calcd for C19H23F2NO2: C, 68.04; H, 6.91; N, 4.18; found: C, 68.09; H, 6.91; N, 4.26.

A-((E)-4-[18F]fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-fluorophenyl)nortropane ([18F]9)

Nor-β-CFT25 (∼1.9 mg) was dissolved in DMF (0.3 mL) and added to the V-tube containing [18F]14. The mixture was heated at 105 °C for 15 min and then cooled in a 0 °C ice bath for 1 min. The mixture was diluted with HPLC solvent (∼0.5 mL) and purified by semi-preparative HPLC (9.1 mL/min; tR = 17-21 min (range)). The desired fractions were combined, diluted 1:1.5 v/v with H2O, and collected on a Waters C18 Sep-Pak. The Sep-Pak was rinsed with 0.9% saline (35 mL) and then EtOH (0.5 mL). The product was eluted from the Sep-Pak with EtOH (1.5 mL) and collected in a sealed sterile vial containing 0.9% NaCl(aq) (3.5 mL). This solution was passed successively through a 1 μm filter and then a 0.2 μm filter (Acrodisc PTFE) under Ar-pressure and collected in a sealed sterile dose vial containing 0.9% NaCl(aq) (10 mL). The total synthesis time was ∼1 h from addition of the nortropane to [18F]14 with a 24% radiochemical yield (decay corrected). The product was then analyzed by analytical HPLC (tr = 3.8 min, 1 mL/min) to determine the radiochemical purity (99%) and specific activity (SA = 851 mCi/μmol).

Compounds 10-13 were prepared in a similar manner as compound 9. Compounds [18F]10 (SA = 3859 mCi/μmol), [18F]11 (SA = 1440 mCi/μmol), and [18F]13 (SA: not determined) were prepared in a similar manner as [18F]9.

N-((E)-4-fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-chlorophenyl)nortropane (10)

White needle crystals (22 mg, 21%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.23 (d, 2 H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2 H, J = 9.0 Hz), 5.78 (m, 2 H), 4.83 (dd, 2 H, 2JHF = 47.4 Hz, J = 5.4 Hz), 3.67 (partially resolved dd, 1 H, J = 6.9 Hz, J = 2.7 Hz), 3.50 (s, 3 H), 3.42 (m, 1 H), 3.01 (m, 1 H + 1 H, overlapping resonances), 2.88 (m, 1 H + 1 H, overlapping resonances), 2.58 (td, 1 H, J = 12.6 Hz, J =3.0 Hz), 2.10 (m, 1 H), 2.01 (m, 1 H), 1.74 (m, 1 H), 1.66 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.01, 141.74, 134.33 (d, J = 11.5 Hz), 131.71, 128.95, 128.23, 126.48 (d, J = 16.6 Hz), 83.36 (d, J = 161.7 Hz), 62.49, 61.39, 55.09 (d, J = 1.4 Hz), 52.86, 51.26, 34.20, 33.97, 26.24, 26.06; HRMS (APCI) [MH]+ Calcd for C19H24O2N35 ClF: 352.1474, found: 352.1473; Anal. Calcd for C19H23ClFNO2: C, 64.86; H 6.59; N, 3.98; found: C, 64.81; H, 6.63; N, 3.97; semi-preparative HPLC: tR = 28.5 min (9 mL/min).

N-((E)-4-fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-bromophenyl)nortropane (11)

White needle crystals (20 mg, 19%): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.38 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.14 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.78 (m, 2 H), 4.83 (partially resolved dd, 2 H, 2JHF = 47.3 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.67 (m, 1 H), 3.50 (s, 3 H), 3.42 (m, 1 H), 2.96 (m, 4 H, overlapping resonances), 2.58 (td, 1 H, J = 12.5 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz), 2.06 (m, 2 H), 1.69 (m, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.99, 142.29, 134.33 (d, J = 11.8 Hz), 131.17, 129.38, 126.48 (d, J = 17.2 Hz), 119.85, 83.36 (d, J = 161.7 Hz), 62.49, 61.38, 55.10 (d, J = 1.4 Hz), 51.28, 34.14, 34.05, 26.24, 26.06; HRMS (APCI) [MH]+ Calcd for C19H24O2N79BrF: 396.0969, found: 396.0969; Anal. Calcd for C19H23BrFNO2: C, 57.58; H, 5.85; N, 3.53; found: C, 58.41; H, 5.88; N, 3.62; semi-preparative HPLC: tR = 33.0 min (9 mL/min).

N-((E)-4-fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-iodophenyl)nortropane (12)

White solid (117 mg, 69%): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.02 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.78 (m, 2 H), 4.83 (partially resolved dd, 2 H, 2JHF = 47.1 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.67 (m, 1 H), 3.50 (s, 3 H), 3.42 (m, 1 H), 2.95 (m, 4 H, overlapping resonances), 2.57 (td, 1 H, J = 12.4 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz), 2.05 (m, 2 H), 1.69 (m, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.97, 143.01, 137.11, 134.31 (d, J = 11.8 Hz), 129.72, 126.47 (d, J = 16.6 Hz), 91.34, 83.34 (d, J = 161.7 Hz), 62.46, 61.35, 55.07 (d, J = 1.4 Hz), 52.74, 51.27, 34.10, 34.01, 26.24, 26.03; HRMS (APCI) [MH]+ Calcd for C19H24O2NF127I: 444.0830, found: 444.0830; Anal. Calcd for C19H23FINO2: C, 51.48; H, 5.23; N, 3.16; found: C, 52.07; H, 5.24; N, 3.23; semi-preparative HPLC: tR = 46.6 min (9 mL/min).

N-((E)-4-fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-methylphenyl)nortropane (13)

Colorless syrup (would not crystallize from hexanes) (23 mg, 53%): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.16 (d, 2 H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.08 (d, 2 H, J = 8.1 Hz), 5.79 (m, 2 H), 4.83 (partially resolved dd, 2 H, 2JHF = 47.3 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.66 (m, 1 H), 3.49 (s, 3 H), 3.42 (m, 1 H), 3.01 (m, 1 H + 1 H, overlapping resonances), 2.88 (m, 1 H + 1 H, overlapping resonances), 2.61 (td, 1 H, J = 12.6 Hz, J = 3.0 Hz), 2.29 (s, 3 H), 2.04 (m, 2 H), 1.70 (m, 3 H); HRMS (APCI) [MH]+ Calcd for C20H27O2NF: 332.2020, found: 332.2020; Anal. Calcd for C20H26FNO2: C, 72.48; H, 7.91; N, 4.23; found: C, 72.40; H, 7.86; N, 4.25.

(E)-4-Fluoro-1-tosyloxy-2-butene (14)

(E)-1,4-Ditosyloxy-2-butene (18) (256 mg, 0.65 mmol), Bu4NF (1 M in THF, 0.7 mL), and THF (10 mL) were stirred at reflux under Ar(g) for 30 min. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica (2:1 v/v hexanes/EtOEt) to afford a colorless oil (60 mg, 38 %): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.80 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.36 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.99-5.75 (m, 2 H), 4.84 (ddd, 2 H, 2JFH = 46.5 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz), 4.57 (m, 2 H), 2.46 (s, 3 H).

(E)-4-[18F]Fluoro-1-tosyloxy-2-butene ([18F]14)

H18F was produced with a Siemens 11-MeV RDS 112 cyclotron by employing the 18O(p,n)18F reaction in H218O. The H18F(aq) was transferred to a chemical processing control unit (CPCU), collected on a trap/release cartridge, released with K2CO3(aq) (0.9 mg in 0.6 mL H2O), and combined with a CH3CN solution of Kryptofix-222 (5 mg in 1 mL) in a V-tube. The V-tube was placed in a 110 oC oil bath, the solvent was evaporated under a N2(g) flow, and CH3CN (3 mL) was added and evaporated in order to azeotropically dry the Kryptofix-222/K18F complex. (E)-1,4-ditosyloxy-2-butene (18) (4 mg in 1 mL CH3CN) was added, the reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 10 min, and [18F]14 was trapped on a Waters silica Sep-Pak Classic (WAT051900) (previously prepped with 10 mL EtOEt). Compound [18F]14 was eluted with EtOEt, the EtOEt solution was transferred to a hot cell under N2(g) pressure and collected in a V-tube. The V-tube was placed in an 80 °C oil bath and the EtOEt was evaporated with an Ar(g) flow. The solution of radiolabeling precursor was then added to this V-tube.

(E)-1,4-Diacetoxy-2-butene (16)

Trans-1,4-dibromo-2-butene (15) (1.98 g, 9.26 mmol), KOAc (4.70 g, 47.89 mmol, 5.2 equiv.), and AcOH (25 mL) were stirred at reflux under Ar(g) for 21 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, filtered, the precipitate was rinsed with toluene, and the AcOH was removed from the filtrate azeotropically with toluene to give a wet white solid that was dried under vacuum for ∼ 10 min. The solid was suspended in CH2Cl2 and purified by vacuum flash chromatography on silica (13 cm h × 4 cm i.d.): hexanes (100 mL), v/v hexanes/CH2Cl2 – 3:1 (200 mL), 1:1 (200 mL), 1:3 (200 mL), CH2Cl2 (900 mL), to afford a colorless oil (1.04 g, 65 %): TLC Rf = 0.4 (silica, CH2Cl2, I2 vapor); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.86 (septet, 2 H, J = 1.4 Hz), 4.58 (dd, 4 H, J = 1.4 Hz), 2.08 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.86, 128.23, 64.07, 21.08.

(E)-1,4-Dihydroxy-2-butene (17)

(E)-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (16) (2.08 g, 12.08 mmol), HCl (2.0 M EtOEt, 0.9 mL, 1.8 mmol, 0.15 equiv.), and EtOH (75 mL) were stirred at reflux under Ar(g) for 16 h, cooled, and the solvent was removed to afford a faint yellow oil (1.04 g, 98 %): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.90 (m, 2 H), 4.18 (m, 4 H).

(E)-1,4-Ditosyloxy-2-butene (18)

(E)-1,4-Dihydroxy-2-butene (17) (326 mg, 3.70 mmol), p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (1.76 g, 9.23 mmol, 2.5 equiv.), and THF (30 mL) were combined and cooled to 0 °C under Ar(g) followed by addition of sodium t-butoxide (1.07 g, 11.13 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) in portions. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight followed by addition of H2O (100 mL) and then extraction with CH2Cl2 (25 mL × 3). The combined CH2Cl2 extracts were dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica (3:1:1 v/v/v hexanes/EtOEt/CH2Cl2) to afford white crystals (1.21 g, 82 %): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (d, 4 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.35 (d, 4 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.74 (m, 2 H), 4.48 (m, 4 H), 2.46 (s, 6 H).

Figure 5.

MicroPET baseline TACs obtained by injection of [18F]11 into an anesthetized cynomolgus monkey.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the NIMH (1-R21-MH-66622-01). We acknowledge the use of shared instrumentation provided by grants from the NIH and the NSF. Lauryn M. Daniel thanks the Behavioral Research Advancements in Neuroscience (BRAIN) program, part of the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience (www.cbn-atl.org), for a summer research opportunity.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Thie JA. Understanding the Standardized Uptake Value, Its Methods, and Implications for Usage. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1431–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentourkia M, Zaidi H. Tracer Kinetic Modeling in PET. PET Clin. 2007;2:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giros B, El Mestikawy S, Godinot N, Zheng K, Han H, Yang-Feng T, Caron MG. Cloning, Pharmacological Characterization, and Chromosome Assignment of the Human Dopamine Transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson N. The Family of Na+/Cl- Neurotransmitter Transporters. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1785–1803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenhofer G. The Role of Neuronal and Extraneuronal Plasma Membrane Transporters in the Inactivation of Peripheral Catecholamines. Pharmacol Therap. 2001;91:35–62. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Plasma Membrane Monoamine Transporters: Structure, Regulation and Function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nirenberg MJ, Vaughan RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ, Pickel VM. The Dopamine Transporter is Localized to Dendritic and Axonal Plasma Membranes of Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:436–447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00436.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciliax BJ, Drash GW, Staley JK, Haber S, Mobley CJ, Miller GW, Mufson EJ, Mash DC, Levey AI. Immunocytochemical Localization of the Dopamine Transporter in Human Brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:38–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990621)409:1<38::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niznik HB, Fogel EF, Fassos FF, Seeman P. The Dopamine Transporter Is Absent in Parkinsonian Putamen and Reduced in the Caudate Nucleus. J Neurochem. 1991;56:192–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinaglia G, Alvarez FJ, Probst A, Palacios JM. Mesostriatal and Mesolimbic Dopamine Uptake Binding Sites are Reduced in Parkinson's Disease and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: A Quantitative Autoradiographic Study Using [3H]Mazindol. Neuroscience. 1992;49:317–327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90099-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular Pathways of Neurodegeneration in Parkinson's Disease. Science. 2003;302:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazei-Robison MS, Couch RS, Shelton RC, Stein MA, Blakely RD. Sequence Variation in the Human Dopamine Transporter Gene in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:724–736. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer HS, Hahn IH, Moran TH. Abnormal Dopamine Uptake Sites in Postmortem Striatum from Patients with Tourette's Syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:558–562. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laruelle M, Slifstein M, Huang Y. Positron Emission Tomography: Imaging and Quantification of Neurotransporter Availability. Methods. 2002;27:287–299. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talbot PS, Laruelle M. The Role of In Vivo Molecular Imaging with PET and SPECT in the Elucidation of Psychiatric Drug Action and New Drug Development. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12:503–511. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CM, Farde L. Using Positron Emission Tomography to Facilitate CNS Drug Development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine Receptors on Dopamine Transporters Are Related to Self-Administration of Cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheffel U, Boja JW, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine Receptors: In Vivo Labeling with 3H-(-)-Cocaine, 3H-WIN 35,065-2, and 3H-WIN 35,428. Synapse. 1989;4:390–392. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll FI, Howell LL, Kuhar MJ. Pharmacotherapies for Treatment of Cocaine Abuse: Preclinical Aspects. J Med Chem. 1999;42:2721–2736. doi: 10.1021/jm9706729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll FI. 2002 Medicinal Chemistry Division Award Address: Monoamine Transporters and Opioid Receptors. Targets for Addiction Therapy. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1775–1794. doi: 10.1021/jm030092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke RL, Daum SJ, Gambino AJ, Aceto MD, Pearl J, Levitt M, Cumiskey WR, Bogado EF. Compounds Affecting the Central Nervous System. 4. 3β-Phenyltropane-2-carboxylic Esters and Analogs. J Med Chem. 1973;16:1260–1267. doi: 10.1021/jm00269a600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boja JW, Carroll FI, Rahman MA, Philip A, Lewin AH, Kuhar MJ. New, Potent Cocaine Analogs: Ligand Binding and Transport Studies in Rat Striatum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;184:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90627-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boja JW, Patel A, Carroll FI, Rahman MA, Philip A, Lewin AH, Kopajtic TA, Kuhar MJ. [125I]RTI-55: A Potent Ligand for Dopamine Transporters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;194:133–134. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90137-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll FI, Gao Y, Rahman MA, Abraham P, Parham K, Lewin AH, Boja JW, Kuhar MJ. Synthesis, Ligand Binding, QSAR, and CoMFA Study of 3β-(p-Substituted phenyl)tropane-2β-carboxylic Acid Methyl Esters. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2719–2725. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltzer PC, Liang AY, Brownell AL, Elmaleh DR, Madras BK. Substituted 3-Phenyltropane Analogs of Cocaine: Synthesis, Inhibition of Binding at Cocaine Recognition Sites, and Positron Emission Tomography Imaging. J Med Chem. 1993;36:855–862. doi: 10.1021/jm00059a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson AA, DaSilva JN, Houle S. In Vivo Evaluation of [11C]- and [18F]-Labelled Cocaine Analogues as Potential Dopamine Transporter Ligands for Positron Emission Tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(95)02044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundkvist C, Halldin C, Swahn CG, Ginovart N, Farde L. Different Brain Radioactivity Curves in a PET Study with [11C]β-CIT Labelled in Two Different Positions. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:343–350. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoder KK, Hutchins GD, Mock BH, Fei X, Winkle WL, Gitter BD, Territo PR, Zheng QH. Dopamine Transporter Binding in Rat Striatum: A Comparison of [O-methyl-11C]β-CFT and [N-methyl-11C]β-CFT. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular Imaging with PET. Chem Re30v. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wernick MN, Aarsvold JN. The Fundamentals of PET and SPECT. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA; London, UK: 2004. Emission Tomography: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin CS, Hoffman EJ. Calculation of Positron Range and Its Effect on the Fundamental Limit of Positron Emission Tomography System Spatial Resolution. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:781–799. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/3/019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Böhm HJ, Banner D, Bendels S, Kansy M, Kuhn B, Müller K, Obst-Sander U, Stahl M. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:637–643. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200301023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun S, Adejare A. Fluorinated Molecules as Drugs and Imaging Agents in the CNS. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1457–1464. doi: 10.2174/156802606777951046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in Pharmaceuticals: Looking Beyond Intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagmann WK. The Many Roles for Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4359–4369. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai L, Lu S, Pike VW. Chemistry with [18F]Fluoride Ion. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:2853–2873. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakash GKS, Hu J. Selective Fluoroalkylations with Fluorinated Sulfones, Sulfoxides, and Sulfides. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:921–930. doi: 10.1021/ar700149s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirk KL. Fluorination in Medicinal Chemistry: Methods, Strategies, and Recent Developments. Org Pro Res Dev. 2008;12:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haaparanta M, Bergman J, Laakso A, Hietala J, Solin O. [18F]CFT ([18F]WIN 35,428), A Radioligand to Study the Dopamine Transporter With PET: Biodistribution in Rats. Synapse. 1996;23:321–327. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199608)23:4<321::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laakso A, Bergman J, Haaparanta M, Vilkman H, Solin O, Hietala J. [18F]CFT ([18F]WIN 35,428), A Radioligand to Study the Dopamine Transporter With PET: Characterization in Human Subjects. Synapse. 1998;28:244–250. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199803)28:3<244::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stehouwer JS, Goodman MM. Fluorine-18 Radiolabeled PET Tracers for Imaging Monoamine Transporters: Dopamine, Serotonin, and Norepinephrine. PET Clin. 2009;4:101–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman MM, Kilts CD, Keil R, Shi B, Martarello L, Xing D, Votaw J, Ely TD, Lambert P, Owens MJ, Camp VM, Malveaux E, Hoffman JM. 18F-Labeled FECNT: A Selective Radioligand for PET Imaging of Brain Dopamine Transporters. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundkvist C, Halldin C, Ginovart N, Swahn CG, Farde L. [18F]β-CIT-FP Is Superior to [11C]β-CIT-FP for Quantitation of the Dopamine Transporter. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:621–627. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deterding TA, Votaw JR, Wang CK, Eshima D, Eshima L, Keil R, Malveaux E, Kilts CD, Goodman MM, Hoffman JM. Biodistribution and Radiation Dosimetry of the Dopamine Transporter Ligand [18F]FECNT. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:376–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tipre DN, Fujita M, Chin FT, Seneca N, Vines D, Liow JS, Pike VW, Innis RB. Whole-Body Biodistribution and Radiation Dosimetry Estimates for the PET Dopamine Transporter Probe 18F-FECNT in Non-Human Primates. Nucl Med Commun. 2004;25:737–742. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000133074.64669.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis MR, Votaw JR, Bremner JD, Byas-Smith MG, Faber TL, Voll RJ, Hoffman JM, Grafton ST, Kilts CD, Goodman MM. Initial Human PET Imaging Studies with the Dopamine Transporter Ligand 18F-FECNT. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:855–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaly T, Dhawan V, Kazumata K, Antonini A, Margouleff C, Dahl JR, Belakhlef A, Margouleff D, Yee A, Wang S, Tamagnan G, Neumeyer JL, Eidelberg D. Radiosynthesis of [18F]N-3-Fluoropropyl-2-β-Carbomethoxy-3-β-(4-Iodophenyl) Nortropane and the First Human Study With Positron Emission Tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kazumata K, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Antonini A, Margouleff C, Belakhlef A, Neumeyer J, Eidelberg D. Dopamine Transporter Imaging with Fluorine-18-FPCIT and PET. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1521–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robeson W, Dhawan V, Belakhlef A, Ma Y, Pillai V, Chaly T, Margouleff C, Bjelke D, Eidelberg D. Dosimetry of the Dopamine Transporter Radioligand 18F-FPCIT in Human Subjects. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yaqub M, Boellaard R, van Berckel BNM, Ponsen MM, Lubberink M, Windhorst AD, Berendse HW, Lammertsma AA. Quantification of Dopamine Transporter Binding Using [18F]FP-β-CIT and Positron Emission Tomography. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laruelle M. The Role of Model-Based Methods in the Development of Single Scan Techniques. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:637–642. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Logan J. Graphical Analysis of PET Data Applied to Reversible and Irreversible Tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neumeyer JL, Tamagnan G, Wang S, Gao Y, Milius RA, Kula NS, Baldessarini RJ. N-Substituted Analogs of 2β-Carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-iodophenyl)tropane (β-CIT) with Selective Affinity to Dopamine or Serotonin Transporters in Rat Forebrain. J Med Chem. 1996;39:543–548. doi: 10.1021/jm9505324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodman MM, Keil R, Shoup TM, Eshima D, Eshima L, Kilts C, Votaw J, Camp VM, Votaw D, Smith E, Kung MP, Malveaux E, Watts R, Huerkamp M, Wu D, Garcia E, Hoffman JM. Fluorine-18-FPCT: A PET Radiotracer for Imaging Dopamine Transporters. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koivula T, Marjamäki P, Haaparanta M, Fagerholm V, Grönroos T, Lipponen T, Perhola O, Vepsäläinen J, Solin O. Ex Vivo Evaluation of N-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl)nortropane in Rats. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JL, Parhi AK, Oya S, Lieberman B, Kung MP, Kung HF. 2-(2'-((Dimethylamino)methyl)-4′-(3-[18F]fluoropropoxy)-phenylthio)benzenamine for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Serotonin Transporters. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zoghbi SS, Shetty U, Ichise M, Fujita M, Imaizumi M, Liow JS, Shah J, Musachio JL, Pike VW, Innis RB. PET Imaging of the Dopamine Transporterwith 18F-FECNT: A Polar Radiometabolite Confounds Brain Radioligand Measurements. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luurtsema G, Schuit RC, Takkenkamp K, Lubberink M, Hendrikse NH, Windhorst AD, Molthoff CFM, Tolboom N, van Berckel BNM, Lammertsma AA. Peripheral Metabolism of [18F]FDDNP and Cerebral Uptake of its Labelled Metabolites. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen P, Kilts CD, Camp VM, Ely TD, Keil R, Malveaux E, Votaw J, Hoffman JM, Goodman MM. Synthesis, characterization and in vivo evaluation of (N-(E)-4-[18F]fluorobut-2-en-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-substituted-phenyl)nortropanes for imaging DAT by PET. J Labelled Cpd Radiopharm. 1999;42(1):S400. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goodman MM, Chen P. Fluoroalkenyl Nortropanes. US 6,344,179 B1. 2002 Feb 5;

- 61.Goodman MM, Kung MP, Kabalka GW, Kung HF, Switzer R. Synthesis and Characterization of Radioiodinated N-(3-Iodopropen-1-yl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)tropanes: Potential Dopamine Reuptake Site Imaging Agents. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1535–1542. doi: 10.1021/jm00036a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malison RT, Vessotskie JM, Kung MP, McElgin W, Romaniello G, Kim HJ, Goodman MM, Kung HF. Striatal Dopamine Transporter Imaging in Nonhuman Primates with Iodine-123-IPT SPECT. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:2290–2297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim HJ, Im JH, Yang SO, Moon DH, Ryu JS, Bong JK, Nam KP, Cheon JH, Lee MC, Lee HK. Imaging and Quantitation of Dopamine Transporters with Iodine-123-IPT in Normal and Parkinson's Disease Subjects. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1703–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chalon S, Hall H, Saba W, Garreau L, Dollé F, Halldin C, Emond P, Bottlaender M, Deloye JB, Helfenbein J, Madelmont JC, Bodard S, Mincheva Z, Besnard JC, Guilloteau D. Pharmacological Characterization of (E)-N-(4-Fluorobut-2-enyl)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4′-tolyl)nortropane (LBT-999) as a Highly Promising Fluorinated Ligand for the Dopamine Transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:147–152. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riss PJ, Hummerich R, Schloss P. Synthesis and Monoamine Uptake Inhibition of Conformationally Constrained 2β-Carbomethoxy-3β-phenyl Tropanes. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:2688–2698. doi: 10.1039/b902863c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riss PJ, Debus F, Hummerich R, Schmidt U, Schloss P, Lueddens H, Roesch F. Ex Vivo and In Vivo Evaluation of [18F]PR04.MZ in Rodents: A Selective Dopamine Transporter Imaging Agent. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1480–1487. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stehouwer JS, Chen P, Voll RJ, Williams L, Votaw JR, Howell LL, Goodman MM. PET Imaging of the Dopamine Transporter with [18F]FBFNT. J Labelled Cpd Radiopharm. 2007;50(1):S335. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boja JW, Kuhar MJ, Kopajtic T, Yang E, Abraham P, Lewin AH, Carroll FI. Secondary Amine Analogues of 3β-(4′-Substituted phenyl)tropane-2β-carboxylic Acid Esters and N-Norcocaine Exhibit Enhanced Affinity for Serotonin and Norepinephrine Transporters. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1220–1223. doi: 10.1021/jm00034a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raphael RA. Synthesis of Carbohydrates by Use of Acetylenic Precursors. Part II. Addition Reactions of cis- and trans-But-2-ene-1,4-diol Diacetates. Synthesis of DL-Erythrulose. J Chem Soc. 1952:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouquillon S, Muzart J. Palladium(0)-Catalyzed Isomerization of (Z)-1,4-Diacetoxy-2-butene - Dependence of η1- η3-Allylpalladium as a Key Intermediate on the Solvent Polarity. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:3301–3305. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Organ MG, Cooper JT, Rogers LR, Soleymanzadeh F, Paul T. Synthesis of Stereodefined Polysubstituted Olefins. 1. Sequential Intermolecular Reactions Involving Selective, Stepwise Insertion of Pd(0) into Allylic and Vinylic Halide Bonds. The Stereoselective Synthesis of Disubstituted Olefins. J Org Chem. 2000;65:7959–7970. doi: 10.1021/jo001045l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miller AEG, Biss JW, Schwartzman LH. Reductions with Dialkylaluminum Hydrides. J Org Chem. 1959;24:627–630. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dollé F, Emond P, Mavel S, Demphel S, Hinnen F, Mincheva Z, Saba W, Valette H, Chalon S, Halldin C, Helfenbein J, Legaillard J, Madelmont JC, Deloye JB, Bottlaender M, Guilloteau D. Synthesis, radiosynthesis and in vivo preliminary evaluation of [11C]LBT-999, a selective radioligand for the visualisation of the dopamine transporter with PET. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baldwin SW, Jeffs PW, Natarajan S. Preparation of Norcocaine. Synthetic Comm. 1977;7:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lemaire C, Plenevaux A, Aerts J, Del Fiore G, Brihaye C, Le Bars D, Comar D, Luxen A. Solid Phase Extraction - An Alternative to the Use of Rotary Evaporators for Solvent Removal in the Rapid Formulation of PET Radiopharmaceuticals. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1999;42:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dischino DD, Welch MJ, Kilbourn MR, Raichle ME. Relationship Between Lipophilicity and Brain Extraction of C-11-Labeled Radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:1030–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waterhouse RN. Determination of Lipophilicity and Its Use as a Predictor of Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration of Molecular Imaging Agents. Mol Imag Biol. 2003;5:376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilson AA, Houle S. Radiosynthesis of Carbon-11 Labelled N-Methyl-2-(arylthio)benzylamines: Potential Radiotracers for the Serotonin Reuptake Receptor. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1999;42:1277–1288. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilson AA, Jin L, Garcia A, DaSilva JN, Houle S. An Admonition When Measuring the Lipophilicity of Radiotracers Using Counting Techniques. Appl Radiat Isot. 2001;54:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Plisson C, McConathy J, Martarello L, Malveaux EJ, Camp VM, Williams L, Votaw JR, Goodman MM. Synthesis, Radiosynthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Carbon-11 and Iodine-123 Labeled 2β-Carbomethoxy-3β-[4′-((Z)-2-haloethenyl)phenyl]tropanes: Candidate Radioligands for in Vivo Imaging of the Serotonin Transporter. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1122–1135. doi: 10.1021/jm030384e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB. Neurotransmitter Receptor and Transporter Binding Profile of Antidepressants and Their Metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1305–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hyttel J, Bøgesø KP, Perregaard J, Sánchez C. The Pharmacological Effect of Citalopram Resides in the (S)-(+)-Enantiomer. J Neural Transm. 1992;88:157–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01244820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee CM, Javitch JA, Snyder SH. Characterization of [3H]Desipramine Binding Associated with Neuronal Norepinephrine Uptake Sites in Rat Brain Membranes. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1515–1525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01515.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duncan GE, Little KY, Kirkman JA, Kaldas RS, Stumpf WE, Breese GR. Autoradiographic Characterization of [3H]Imipramine and [3H]Citalopram Binding in Rat and Human Brain: Species Differences and Relationships to Serotonin Innervation Patterns. Brain Research. 1992;591:181–197. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91699-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheetham SC, Viggers JA, Butler SA, Prow MR, Heal DJ. [3H]Nisoxetine - A Radioligand for Noradrenaline Reuptake Sites: Correlation With Inhibition of [3H]Noradrenaline Uptake and Effects of DSP-4 Lesioning and Antidepressant Treatments. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Neumeyer JL, Wang S, Milius RA, Baldwin RM, Zea-Ponce Y, Hoffer PB, Sybirska E, Al-Tikriti M, Charney DS, Malison RT, Laruelle M, Innis RB. [123I]-2β-Carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)tropane: High-Affinity SPECT Radiotracer of Monoamine Reuptake Sites in Brain. J Med Chem. 1991;34:3144–3146. doi: 10.1021/jm00114a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carroll FI, Kotian P, Dehghani A, Gray JL, Kuzemko MA, Parham KA, Abraham P, Lewin AH, Boja JW, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine and 3β-(4′-Substituted phenyl)tropane-2β-carboxylic Acid Ester and Amide Analogues. New High-Affinity and Selective Compounds for the Dopamine Transporter. J Med Chem. 1995;38:379–388. doi: 10.1021/jm00002a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuhar MJ, McGirr KM, Hunter RG, Lambert PD, Garrett BE, Carroll FI. Studies of Selected Phenyltropanes at Monoamine Transporters. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petric A, Barrio JR, Namavari M, Huang SC, Satyamurthy N. Synthesis of 3β-(4-[18F]Fluoromethylphenyl)- and 3β-(2-]18F]Fluoromethylphenyl)tropane-2β- Carboxylic Acid Methyl Esters: New Ligands for Mapping Brain Dopamine Transporter With Positron Emission Tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stout D, Petric A, Satyamurthy N, Nguyen Q, Huang SC, Namavari M, Barrio JR. 2β-Carbomethoxy-3β-(4- and 2-[18F]Fluoromethylphenyl)tropanes: Specific Probes for In Vivo Quantification of Central Dopamine Transporter Sites. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:897–903. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cook CD, Carroll FI, Beardsley PM. RTI 113, a 3-Phenyltropane Analog, Produces Long-Lasting Cocaine-Like Discriminative Stimulus Effects in Rats and Squirrel Monkeys. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;442:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kimmel HL, Negus SS, Wilcox KM, Ewing SB, Stehouwer J, Goodman MM, Votaw JR, Mello NK, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Relationship Between Rate of Drug Uptake in Brain and Behavioral Pharmacology of Monoamine Transporter Inhibitors in Rhesus Monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behavior. 2008;90:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsukada H, Nishiyama S, Kakiuchi T, Ohba H, Sato K, Harada N, Nakanishi S. Isoflurane Anesthesia Enhances the Inhibitory Effects of Cocaine and GBR12909 on Dopamine Transporter: PET Studies in Combination with Microdialysis in the Monkey Brain. Brain Research. 1999;849:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mizugaki M, Nakagawa N, Nakamura H, Hishinuma T, Tomioka Y, Ishiwata S, Ido T, Iwata R, Funaki Y, Itoh M, Higuchi M, Okamura N, Fujiwara T, Sato M, Shindo K, Yoshida S. Influence of Anesthesia on Brain Distribution of [11C]Methamphetamine in Monkeys in Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Study. Brain Research. 2001;911:173–175. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02669-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsukada H, Nishiyama S, Kakiuchi T, Ohba H, Sato K, Harada N. Ketamine Alters the Availability of Striatal Dopamine Transporter as Measured by [11C]β-CFT and [11C]β-CIT-FE in the Monkey Brain. Synapse. 2001;42:273–280. doi: 10.1002/syn.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Elfving B, Bjørnholm B, Knudsen GM. Interference of Anaesthetics With Radioligand Binding in Neuroreceptor Studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:912–915. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Votaw J, Byas-Smith M, Hua J, Voll R, Martarello L, Levey AI, Bowman FD, Goodman M. Interaction of Isoflurane With the Dopamine Transporter. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:404–411. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Votaw JR, Byas-Smith MG, Voll R, Halkar R, Goodman MM. Isoflurane Alters the Amount of Dopamine Transporter Expressed on the Plasma Membrane in Humans. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1128–1135. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eckelman WC, Kilbourn MR, Mathis CA. Discussion of Targeting Proteins In Vivo: In Vitro Guidelines. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ryu YH, Liow JS, Zoghbi S, Fujita M, Collins J, Tipre D, Sangare J, Hong J, Pike VW, Innis RB. Disulfiram Inhibits Defluorination of 18F-FCWAY, Reduces Bone Radioactivity, and Enhances Visualization of Radioligand Binding to Serotonin 5-HT1A Receptors in Human Brain. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1154–1161. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]