Abstract

The environment of care can have a profound impact on caregiving experiences of families caring for loved ones with a life-limiting illness. Care is often delivered through disease-specific specialty clinics that are shaped by the illness trajectory. In this study, the following 3 distinct cultures of care were identified: interdisciplinary, provider dominant, and cooperative network. Each of these cultures was found to express unique values and beliefs through 5 key characteristics: acknowledgment of the certainty of death, role of the formal caregiver, perception of the patient system, focus of the patient visit across the trajectory, and continuum of care across the trajectory.

Keywords: culture of care, informal caregiver, life-limiting illness, specialty clinics, supportive care

Modern health care delivery systems have developed in response to the need for short-term health care.1,2 While this care delivery system has advanced exemplary episodic and urgent care, there is a persistent discrepancy in focus between short- and long-term care. Seventy percent of all deaths in the United States are attributed to chronic conditions,3 and 75% of all health care expenditures in the United States are related to their management.4 The current environment of health care delivery often fails to address the complex care demands of living with chronic, life-limiting illnesses, especially during the prolonged non–short-term phases.5 The purpose of this article is to compare and contrast key characteristics of the culture of care in care delivery environments serving patients with life-limiting chronic conditions.

Care for patients with complex life-limiting chronic illness is often delivered through disease-specific, specialty outpatient clinics.5–7 Not to be confused with end-of-life specialty clinics, these outpatient clinics serve patients and families for nonacute illnesses. The impact of this system of specialty care delivery has been well documented, including improved quality of care and health status,8 decreased hospital admissions,9 prevention of clinical deterioration, and avoidance of acute health crises.10,11 Clearly, this organization of services is effective in providing clinical expertise targeted at a specific illness12; however, there is a range of services designed to support families living through the illness experience that are underutilized.

The service menu of many specialty clinics typifies a dominant biomedical paradigm13 with a focus on monitoring pathology, treatment, and management of symptoms. Far fewer clinics focus on the provision of care that addresses not only physical needs but also the psychosocial concerns of living with a life-limiting chronic condition.14,15 Considering that the chronic illness experience permeates everyday life, accessibility of specialty care is often an issue. While some specialty clinics offer services on a daily basis in a fully staffed clinic, far more offer more limited access on an intermittent weekly or monthly schedule.5

This degree of variability in the environment of care for life-limiting chronic illnesses can have a profound impact on the experiences of patients and families living each day under the specter of a serious, incurable illness. In the various environments, health care providers are challenged to effectively communicate treatment options, provide patient education, deliver follow-up care, and aid in decision making from diagnosis through end of life.16 For example, a critical consideration in the care of those with chronic conditions would be advanced care planning; however, this is not always the case in the specialty clinic setting. End-of-life discussions can be emotionally difficult for the patient, family, and the health care provider who must constantly determine the best ways to communicate with patients and caregivers about the illness experience.17 As a result, end-of-life discussions often do not occur until the final hours, days, or minutes of life.

Specialty clinics provide health care that is largely administered through teams to achieve common goals18 and outcomes19 that are influenced by shared understandings, ideas, and values.20 The beliefs and values that are embraced by a culture such as a specialty clinic provide the underlying rationale for how members of the culture think and behave as well as influence perceptions about the types of useful treatments, probable outcomes of health behaviors associated with the prevention and control of illness, as well as the meaning of the illness experience.21 Thus, these cultural elements comprising health care providers’ beliefs and belief systems about the total delivery of health service for patients as well as their caregivers influence care delivery.22

Culture is composed of both explicit and implicit shared values and beliefs that are manifest in acquired patterns of behaviors. Different types of health care cultures have been linked to performance outcomes such as quality improvement,23 functioning of teams,24 and evidence-based practice.25 Shared values and beliefs are observable at multiple levels including institutional frameworks that influence decision making and patient-provider interactions; distinct work flow procedures; and defined roles for health care providers, support staff, patients, and family caregivers.25 From structural and process components of the delivery system to the more abstract level of ideas,20 cultural influences shape patterns of behavior in care delivery. Thus, implicit or explicit values and beliefs of the organizational unit of the specialty clinic shape the culture of care in that practice environment.

In turn, translation of that culture of care into ongoing care interactions has a tremendous impact not only on patients but also on the informal caregivers who share the illness experience. Informal caregivers (defined as persons who provide direct care or supportive care without compensation) are instrumental partners in the care delivery system. In 2009, the economic value associated with informal caregiver services in the United States was conservatively estimated to be $450 billion per year.26 Informal caregiving is difficult work with a well-documented physical, social, financial, and emotional toll.27–30 Especially in the context of life-limiting chronic illness, the duration of informal caregiving often extends over years, beginning when the patient is diagnosed, continuing through treatment until the death of the patient. Because of the profound impact of informal care-giving, it is crucial that these partners in care not be viewed merely as coproviders of care to patients but also considered as care recipients with their own unique needs.31

The protracted trajectory of caregiving through the end-of-life has been modeled by Penrod and colleagues.32,33 The unifying theme of the theory is “seeking normal,” a process through which informal caregivers strive to achieve a steady state (or sense of normal) amidst ever-changing demands in their care-giving role. The theory delineates 4 phases of caregiving from diagnosis through bereavement marked by key transitions when the progression of illness challenges an established “steady state” of the caregiver. Transitions prompt a disruption, predisposing the informal caregiver to once again seek a new state of normal by building new patterns integrating care demands into everyday life.

The progression and duration of the care-giving phases are reflective of the course of the illness and the acknowledgment that the end of life is approaching. Using classic models of death trajectories as a foundation,34,35 Penrod and colleagues36 have further described theoretical variations in the caregiving experience in an expected trajectory (eg, the “terminal” diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]), an unexpected trajectory (eg, the “serious” diagnosis of heart failure [HF]), and a mixed trajectory featuring intensive curative attempts followed by a period of comfort care (eg, lung cancer). As indicated by the trajectory labels, perceptions of the likelihood of death from the life-limiting illness range from an expected, anticipated outcome to a surprising turn of events preceding an unexpected death. However, it is important to note that the life expectancy of persons with these life-limiting illnesses is very similar; death from ALS is likely to ensue within 2 to 5 years of diagnosis,37 less than 10% of individuals with advanced lung cancer survive 5 years,38 and more than half of those with HF die within 5 years.39

Interactions with health care providers in specialty clinics provide critical evidence through which informal caregivers interpret progression of disease and prognosis. These interactions shape their acknowledgment of the probability of death and perceptions of the future. The practice environment of the specialty clinic is fraught with implicit and explicit shared values. This value-laden context sets the frame for the nexus of caregiving systems through which informal caregivers build their understanding of the unfolding scene. Understanding the culture within these care environments is critical in development and evaluation of supportive strategies for informal caregivers. In this article, the key characteristics of the culture of care manifest in specialty clinics serving patient systems (patient and family) with life-limiting illnesses exemplifying 3 distinct caregiving trajectories are described, compared, and contrasted.

METHODS

Informal caregivers interact with health care providers during brief office visits over the course of their charge’s illness. To understand how the experience of the informal caregiver is influenced by these visits, it is necessary to understand the culture of care in outpatient clinical settings. Therefore, ethnographic methods were undertaken to explore and understand the culture that is learned and shared among members of the culture of care in the outpatient specialty clinics. The exploration concentrated on the interaction between health care providers (formal care-givers) and the informal caregiver to identify and interpret patterns of behaviors that reveal implicit and explicit shared values and beliefs.40

PROCEDURE

Approval was obtained from the medical center–based institutional review board for the protection of human participants. Formal caregivers (n = 32) provided written informed consent under principles of full disclosure prior to engagement in the research. Formal caregivers included physicians (n = 7), nurses (n = 18), social worker (n = 1), counselors (n = 2), occupational and physical therapists (n = 3), and administrative staff (n = 3). The majority of the formal caregivers were female (81%). Verbal consent for observation was obtained from informal caregivers (n = 601) and patients prior to the start of the visit. Similar to the formal caregivers, the majority of the informal caregivers were female (79%).

The informal caregiving experience varies in course and duration over various death trajectories.36 To capture the experience of informal caregivers with varied experiences, data were collected in 3 outpatient specialty clinics treating patients and families transversing 3 distinct trajectories: expected (ALS), unexpected (HF), and mixed (lung cancer). These clinics were located in the United States within a quaternary medical center with a large geographic catchment area.

Data collectors (n = 9) for the study were active members of the research team. The team consisted of 2 senior researchers with extensive experience in qualitative research methods and 7 junior researchers who underwent extensive training in observational data collection techniques and completed a university-based graduate-level course in qualitative methods. Although data collectors’ primary assignments were in a specific clinic, they observed interactions in all clinics to increase validity of clinic comparisons and contrasts. Researchers remained nonintrusive and nonparticipatory during 12 months of immersion in the clinics. Naturalistic visual and auditory observations of 601 office visits were made during clinic hours. Observations focused on verbal and nonverbal interactions between formal and informal caregivers. Examples of observed interactions included communication extending from discussion of patient symptom management and availability of caregiver respite services to comforting behaviors offered to informal caregivers by their formal caregiver counterparts. To enrich the observational data, formal caregivers were interviewed briefly to provide information regarding the meaning behind their actions during these interactions. To fully capture influences upon the observed interactions, data such as general clinic observations, support group observations, and educational/support materials were collected. Observations and formal caregiver responses to brief interviews were recorded digitally as field notes. The recordings were then transcribed verbatim and verified for accuracy. To protect the participants’ confidentiality, all personally identifying information was replaced with generic identifiers (eg, physician).

ANALYSIS

Analytic methods described by LeCompte and Schensul40 were used in this study. Analysis began upon researcher immersion in the field with inscription, description, and transcription. Researchers recorded field notes after formal and informal caregiver interactions, brief interviews with the formal caregivers, and informal caregiver support group meetings. Researchers utilized these inscriptions immediately following the observation to digitally record thick description. These recordings were later transcribed verbatim and verified for accuracy by reading the transcribed text, while listening to the audio recording.

The verified transcripts as well as the collection of educational/support materials were then organized and stored within the analytic software platform ATLAS.ti (version 5.7.1, At-lasti, GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for data management. Within 3 months of initial data collection, content analysis began within each clinic and then expanded across the clinics. Data were analyzed inductively through a cyclical, iterative process that progressed from independent item-level analysis to pattern analysis and category codes. Inductive category coding was done simultaneously with comparison to the ongoing observational data collection permitting testing and refinement of early hypotheses as well as the development of relationships.41 Through this process, a large amount of raw data was compressed into a manageable form permitting exposure of patterns and themes.42 Conceptual insights derived through ongoing analyses were used to focus subsequent data collection.40 Analysis continued for 1 year as data collection continued.

Patterns and themes were interpreted by the team through shared insights during weekly team meetings. Consensus was reached on the emergent interpretation of data. Instances of divergent interpretations were resolved by the team’s close examination of the data or continued data collection to clarify interpretation. All research team analysis meetings were digitally recorded to retain accurate records of the decisional audit trail used in analysis.

The rigorous execution of this study is demonstrated with the immersion of the researchers within the clinical setting for 12 months during all hours of clinic operation. Observations were recorded digitally immediately following the interaction to ensure reliability. In addition, all researchers observed in all 3 clinics to verify, confirm, or refute the reliability of inscriptions by other researchers. Finally, findings were presented to key informants in a form of member checking.

FINDINGS

A clinical outpatient setting is a sociocultural organization possessing a culture of care composed of shared values and beliefs. The culture of care as viewed from the lens of the informal caregiver differed in each of the 3 clinical settings that were explored in this study. Within these clinics, culture of care is shaped by the context of the illness. Formal caregivers have expectations regarding the trajectory of an illness and this influences their values and beliefs. These values and beliefs are expressed explicitly and implicitly through the care delivery model, shaping the expectations and thus molding the experience of informal caregivers.

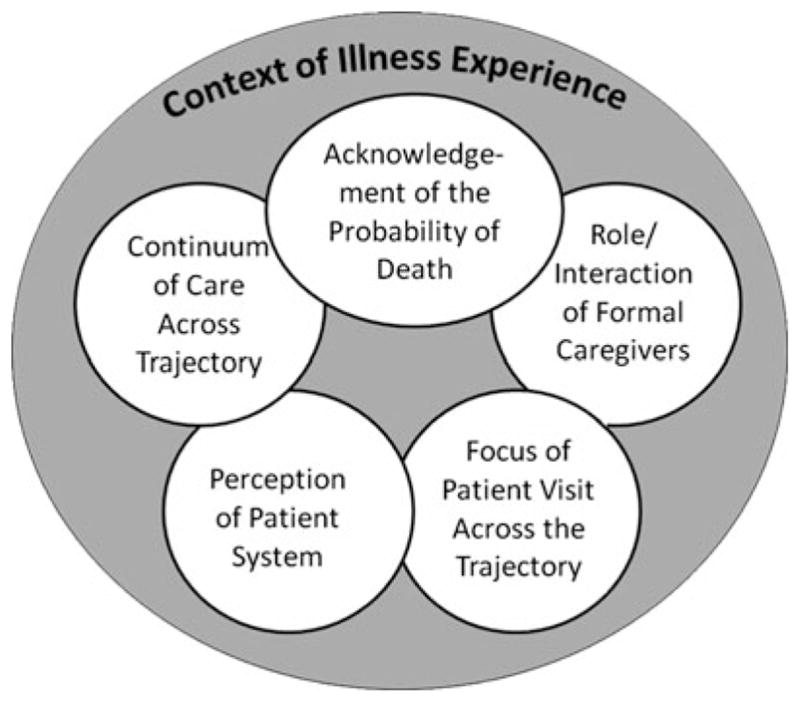

Values and beliefs within each culture of care are expressed through 5 key characteristics: acknowledgment of the probability of death, role of the formal caregiver, perception of the patient system, focus of the patient visit across the trajectory, and continuum of care across the trajectory (Figure). The key characteristics are co-occurring, interdependent spheres of influence that are shaped by the context of the illness. As the spheres do not exist in isolation of one another, if the values and beliefs expressed in one-sphere shifts, there is a corresponding shift in the remaining spheres.

Figure.

Five key characteristics in the culture of care.

In this study, exploration of 3 distinct models of delivery (interdisciplinary, provider dominant, and cooperative network) in the clinics revealed distinct values and beliefs or cultures of care. In the Interdisciplinary care delivery model, health care providers had shared power and dynamically care for patients and families based upon expressed needs. In the provider-dominant model, there is a lead provider and the role of the remaining staff is to solely support that provider. In the Cooperative Network model of care delivery, there is a lead provider; however, other interdisciplinary formal caregivers step in to support patients and families (rather than the lead provider). In each of these care delivery models, unique values and beliefs were expressed through the 5 key characteristics.

Exemplar 1: The culture of care in an interdisciplinary care delivery model

Acknowledgment of the probability of death

The most prominent characteristic within each culture of care is the acknowledgment of probability of death. In this culture of care, the illness is acknowledged by formal caregivers as terminal from diagnosis, thus opening the door to supportive strategies early in the trajectory. Progressive decline is anticipated and supportive care (ie, generalist strategies of comprehensive, holistic care) for the patient and the informal caregiver is infused into clinic visits with an emphasis on quality of life. Informal caregivers are prepared by formal caregivers to anticipate a progressive decline in the patient’s condition followed by an expected death. This shaping of the informal caregiver’s expectations is demonstrated during a particularly difficult clinic visit with a middle-aged woman caring for her husband with rapid progression in his disease. The nurse expressed that it is better to make decisions ahead of time and be comfortable with them so when the time comes, plans are in place. The formal caregiver stressed that it is better to plan in advance for everyone’s sake, for the caregiver as well as for the patient.

Role of the formal caregiver

The role of the formal caregiver in shaping the experience of the informal caregiver can be dramatic. The probability of death is acknowledged within this culture of care permitting cooperation of multiple domains (eg, nursing, sociology, theology, psychology, pathology) with shared power and authority to provide supportive holistic care. Formal caregivers were responsible for providing care within their area of expertise. However, if a need expressed to a team member was seen as out of their realm of knowledge, there was deliberate and purposeful consultation and inclusion of the appropriate team members as noted in the following text:

During an office visit, one of the formal caregivers met with a patient to discuss plans for future care arrangements. As the office visit proceeded, the formal caregiver realized additional expertise was necessary and consulted another member of the health care team to develop a patient-centered resolution.

Perception of the patient system

The formal caregivers’ perception of the patient system shapes the expectations and thus the experience of the informal caregiver. Formal caregivers may perceive the informal caregiver as a coprovider of care within the patient system. In this view, informal care-givers are considered as extenders of care in management of medications, devices, and nutrition. Alternatively, the informal caregiver may be perceived as both a coprovider and a corecipient of care (ie, a target for specific care interventions). In this culture of care, informal caregivers are consistently and purposefully integrated into the visit. Formal caregivers anticipated needs and offered supportive care to informal caregivers as demonstrated in a clinic visit with an informal caregiver and her husband who was experiencing breathing difficulties. The nurse counselor took the informal caregiver into a separate room (as she appeared to be upset) and said to her, “I know you are going through a really rough time right now and as important as your husband is to us, you are equally as important to us. We want to make sure that your emotional needs are being met ….”

Focus of the clinic visit across the trajectory

The focus of the patient visit across the trajectory dynamically shifted to meet the holistic needs of the patient system. There was an emphasis on quality of life through death and into bereavement. This was evidenced in a clinic visit with a daughter who cared for her elderly father. To address the spiritual needs of the patient system, a donated prayer shawl was presented to the patient and the spiritual counselor spent a moment with the daughter to let her know that “there are a lot of people who are rooting for your dad in this clinic and also in the community.”

Continuum of care across the trajectory

The continuum of care across the trajectory addresses the flow of care delivered from diagnosis through death and into bereavement for the informal caregiver. In this culture of care, there was a supportive network of care provided across the trajectory. Care is extended to the patient system with home visits, phone calls, and e-mail communication. In an e-mail to a team member, an informal caregiver of a middle-aged man with limited mobility expressed guilt over being able to do things the patient is no longer able to do. A home visit with the informal caregiver was arranged to support her needs between clinic visits. Even after hospice was initiated, the patient system continued to receive care in the clinic. In fact, contact was not terminated upon the death of the patient as care for the informal caregiver continued well into bereavement.

Summary: Interdisciplinary care delivery model

The culture of care in this Interdisciplinary model of care delivery values informal care-givers and integrates them as a coprovider and corecipient of care from diagnosis through bereavement. Expertise abounds in multiple domains permitting opportunities for the informal caregiver to build trust with selected key personnel based on their needs at any particular time. There are focused efforts on providing instructions for care to the informal caregivers as well as an understanding of the illness experience. Transitions in caregiving are anticipated and focus on the everyday world. The relationship with the team continues through formalized grief support.

Exemplar 2: The culture of care in a provider-dominant care delivery model

Acknowledgment of the probability of death

Death in this care delivery model was rarely anticipated by the formal caregiver. The emphasis in this model was on medical stability, with the illness regarded as chronic and serious but manageable. As a result, death was rarely anticipated and medical management often continued to within days or even hours of death. With the focus on medical management, supportive care for the informal care-giver was not anticipated. This was evidenced by a clinic visit with a woman and her husband with end-stage disease. The patient was experiencing severe shortness of breath and fatigue. Medications were no longer effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms and the next step was an organ transplant. The formal caregiver said to the patient, “Now I am not giving you false hope here. I am just saying that we have other things that we could try, it is a pretty serious situation.” As other options were suggested for medical management, the probability of death was not acknowledged and supportive strategies were not introduced to the caregiver.

Role of the formal caregiver

In the provider-dominant care delivery model, a medical specialist had a solo practice approach. This was evidenced during a clinic visit with a new patient. During the visit, the lead provider completed a history and physical assessment and developed a plan of care. At the end of the visit, the provider escorted the patient and informal caregiver out and communicated the plan of care to the clinic staff. The lead provider retained full responsibility for the “care of the patient” system and was supported in this role by other members of the health care team.

Perception of the patient system

In the provider-dominant care delivery model, the focus of the clinic visit was on the patient’s medical status. The culture of care in this model did not consider the patient system a priority and they were not perceived as a critical part of the clinic visit. The informal caregiver not being an integral part of the culture of care was demonstrated by the following observation:

[The lead provider] had no interaction with family members … during the visit … despite the daughter at one point making a comment about her mother. It seemed as if he and the patient were the only two in the room …. No further comments or questions were asked by [daughter] during the visit.

In order to be recognized, the informal caregiver had to actively call awareness to a concern or need and this, in turn, shaped expectations of the culture of care.

Focus of the clinic visit across the trajectory

During clinic visits in the provider-dominant care delivery model, there is sustained focus on medical stability with careful treatment based on pathology and symptoms. This focus was illustrated by the following observation of a clinic visit with a family and an elderly male patient who was living in a long-term care facility and steadily declining after having a stroke.

The nursing home had stopped one of the medications that this [lead provider] thought that this patient should definitely be on. He was very upset [and] … it was evident that he wanted to continue to try to do everything …. for this patient despite all of his other comorbid diagnoses, but nothing was said to the family. Nothing was asked about end-of-life care or terminating medications or anything like that at this visit.

In this example, even though the patient was steadily declining, the focus was on medically managing the patient and supportive services were not anticipated or discussed with the informal caregivers.

Continuum of care across the trajectory

Clinic visits in the provider-dominant model of care delivery continued across the illness trajectory with treatment options introduced progressively. The belief of the formal caregivers that other treatment options were always available shaped the expectations of the patient system. Death was rarely anticipated in this culture of care and appears to happen suddenly and often without supportive care in place. Such was the example of a patient diagnosed with another life-limiting illness on the transplant list. The plan of care was to bridge the patient to transplant with an assistive device during treatment for the second illness. “Now don’t forget this is just a bump in the road. This is just something that we need to deal with … don’t forget I’m right here with you … we’ll get you through this. We’ll take this step by step and we’ll just do this all together.”

Even though the patient in this example was seriously ill and facing comorbidities that greatly reduced the likelihood of achieving and maintaining medical stability, end-of-life discussions were neither initiated nor were supportive services anticipated for the informal caregiver.

Summary: Provider-dominant care delivery model

Formal caregivers in the provider-dominant model of care delivery focus on the pathology of the patient illness and responsive treatment with a goal of medical stability for the targeted illness. The informal caregivers learned a new language—they learned terminology, pathology, treatment, and symptoms related to their loved ones’ illness. However, expertise was clearly established in the dominant provider and opportunity to build trust with this provider evolved. However, the informal caregivers needed to seek out other support when their needs expand beyond the medical stability that was sought by the dominant provider. The informal caregiver was often unprepared at the time when end of life was acknowledged a short time prior to death. Grief support for the informal caregiver was left to outside community.

Exemplar 3: The culture of care in a cooperative network care delivery model

Acknowledgment of the probability of death

In the Cooperative Network care delivery model, the emphasis was on cure of the medical condition. As a result, the probability of death is acknowledged only after treatment options are ineffective and exhausted, which typically occurs late the trajectory. Once the probability of death was acknowledged, the patient system was then discharged to end-of-life specialty services for supportive end-of-life care. During the clinic visit, the possibility of death was not stated forthright, it was communicated in a roundabout way in which patients may or may not understand the inference. For example, when inquiries of life expectancy were broached by the patient or family, they were encouraged “to live day by day.”

Role of the formal caregiver

In the Cooperative Network care delivery model, formal caregivers were focused on disease progression and symptom management. The emphasis was on curing or stabilizing the disease with attention to other aspects of the illness being provided by supportive formal caregivers. Authority was hierarchical with patient communication and decision-making power under the purview of the lead provider. For example, during a patient assessment, the nurse practitioner noted the progression of disease. Rather than informing the patient directly of these results, the nurse practitioner proceeded to leave the room and informed the lead provider of her conclusions. It was the lead provider who then shared the information with the patient system.

Formal caregivers who practice within this culture of care often conducted debriefing sessions with the patient system that provided opportunity for supportive care. Referrals and consultations to other services were provided on an as-needed basis, which sometimes resulted in fragmented care.

Perception of the patient system

In the Cooperative Network care delivery model, the formal caregivers were focused on the disease status and the patient. The debriefing session was a time when supportive strategies for the informal caregiver were sometimes infused into the visit as revealed during an interaction:

The [informal caregiver] stated … that she did not need any help taking care of [the patient] that she was doing fine. [The nurse practitioner] said that she wanted to make sure that the wife was taken care of because if something happened to her then her husband would be in trouble.

Focus of the patient visit across the trajectory

Disease response to treatment and control of adverse effects occupied much of the focus of a clinic visit in the Cooperative Network care delivery model. During times of difficult treatment regimens with intense adverse effects, the illness experience permeated the clinic visit as demonstrated in the following field note. The focus of this visit had shifted from treatment of the primary disease to treatment of psychosocial issues when the informal caregiver initiated a discussion:

The primary issue that the [informal caregiver] wanted to bring up … was the issue of [patient’s] depression. She feels that it is classic depression … [formal caregiver] asked [informal caregiver] what [patient’s] typical day involved … what time … [patient] gets up?

Continuum of care across the trajectory

Clinic visits were typically heightened during active treatment in the Cooperative Network care delivery model. There were repetitive cycles of treatment and testing to determine response to treatment. If initial treatment failed, the likelihood of cure was diminished. However, clinic visits continued with a new goal: to minimize disease progression. Even at this stage in the trajectory, the reality of a limited life expectancy was unlikely to be addressed. As with the culture of care in the provider-dominant care delivery model, this lack of anticipated support shaped the expectations of the informal caregiver with the focus of care remaining on the treatment of the disease. This was highlighted by the formal caregiver’s interaction with the patient system following initial treatment failure: “We do this chemo and when that does not work, we try something new. If you remain stable then we are good. We are good’ … [The observer remarks that] there was never a mention of preparation for the family of … the death.”

When treatment options were finally exhausted and determined to be ineffective, the patient was abruptly discharged to referring services for end-of-life care (ie, hospice or palliative services). This shift from cure to comfort care can be a difficult transition for the patient and informal caregivers particularly if expectations were shaped around a cure for the disease.

Summary: Cooperative Network care delivery model

The lead provider in the Cooperative Network care delivery model focused on treatment to cure or stabilize the patient’s disease. Other formal caregivers provided support to informal caregivers during debriefing sessions and provided assistance in learning a new language. The lead expert was clearly identifiable, but others in the network provided instrumental support and opportunities for the informal caregiver to build trust with key people. Acknowledgment of end of life may be abrupt, but efforts were made to smooth transition into a new system of care (ie, palliative or hospice care). Grief support is available only through the new system of end-of-life care.

Summary of findings: Culture of care in 3 care delivery models

In this study, the culture of care was shown to be composed of 5 key characteristics: acknowledgment of the probability of death; role of the formal caregiver; perception of the patient system; focus of the visit across the trajectory; and continuum of care across the trajectory. Because of their repeated exposure to a particular trajectory, formal caregivers have expectations that shape their share values and beliefs within the clinical setting. Of the 5 key characteristics, the most prominent is the acknowledgment of the probability of death. Once the probability of death is acknowledged, the focus shifts to accommodate the infusion of supportive care or referral to end-of-life services. This shift is perceived by the patient system through interdependent spheres of influence that comprise the culture of care. In each of the exemplar care delivery in this study (interdisciplinary, provider dominant, and cooperative network), this shift occurred at various times along the trajectory, which critically shaped the experience for the informal caregiver through the illness.

The expectations of the formal caregivers shape the culture of care in the clinical setting, which, in turn, shapes the expectations of the patient and family. Through repeated interactions and reinforcement, the patient system comes to understand what to expect during an interaction with the formal care-givers in the specialty clinics. In the Interdisciplinary culture of care, informal care-givers anticipate that care plans are developed through a team approach. They expect to be integrated into office visits throughout the trajectory and build relationships with key personnel based upon their needs. Additional informal caregiver expectations in this culture of care include focused effort in providing instructions for care and understanding the illness experience; anticipated transitions and focus on their everyday world; and the continuation of care into the bereavement phase through formalized grief support.

The culture of care in the provider-dominant care delivery model is shaped for the informal caregiver by the expectation that the formal caregiver will discuss pathology and treatment response during the office visit. Through experience in interaction with this culture of care, informal caregivers expect to be perceived as coproviders of care. A relationship is formed with the lead provider with little opportunity of developing relationships with other members of the health care team. Informal caregivers providing care within this culture of care expect the patient to maintain medical stability through progressive treatment options. With this focus, the probability of death is typically acknowledged only a short time before death, leaving the informal caregiver unprepared for the transition into bereavement. In addition to being unprepared for the death of their loved one, informal caregivers are not offered nor do they expect grief support to be available through the specialty clinic.

In the Network Cooperative care delivery model, the informal caregiver identifies the lead expert and expects the discussion during office visits to focus on the diagnosis, disease status, and treatment options. With shaped expectations in the culture of care expressed in this care delivery model, the informal care-givers fulfill the role of coproviders for the care of their loved ones. The informal care-giver expects to have ongoing treatment options, so when those options are exhausted, they are often unprepared for the abrupt transition from cure to comfort care. However, referral to end-of-life care services may provide support to the informal caregiver prior to death and into bereavement.

LIMITATIONS

As with most studies there are certain limitations. For this study, they include limited ethnic diversity and clinical sites were within one quaternary medical center.

DISCUSSION

The acknowledgment of the probability of death is pivotal in the caregiving trajectory.36 Even though the end-of-life illnesses in the 3 cultures of care in this study have similar life expectancy, the acknowledgment of the probability of death varies dramatically. Thus, the infusion of supportive services may be delayed or nonexistent. The result is that many informal caregivers remain unsupported.

The negative health effects for informal caregivers are well established.43,44 As such, there is an increased urgency for infusion of supportive strategies for the informal care-giver earlier in the trajectory.45,46 In the 2011 Update, American Association of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute recommends the promotion of new models of care that are family-centered with caregiver support and integration into the care plan by nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals.26 These recommendations are only plausible with shifting values and beliefs of the formal caregivers who deliver care through models. The culture of care frames the notion of the context of the illness within the key characteristics that shift in response to the perception of the formal caregivers. A change in culture does not occur quickly or easily.47 To facilitate shifts in the culture of care, there must be continual and dynamic change in the perception of the acknowledgment of the probability of death. With this type of change, the other 4 interdependent, co-occurring spheres will shift to accommodate this change. Upon acknowledging the probability of death, the role of the formal caregiver, the perception of the patient system, the focus of the visit, and the continuum of care across the trajectory will shift to support the experience of the informal caregiver across the trajectory.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

While the importance of supportive strategies for patients and their families experiencing chronic, debilitating, or life-limiting illnesses has been acknowledged, infusion of supportive services in each of these clinics varied. Despite the fact that patients were diagnosed with an illness transversing 1 of 3 distinct death trajectories in this study, all face a shortened life expectancy (2–5 years). The illnesses were perceived from serious but manageable, chronic, and life-limiting, to terminal. In this study, the acknowledgment of the probability of death was a pivotal factor in the provision of supportive end-of-life care.37–39

Essential tenets of supportive care direct health care professionals to address the needs of family and other informal caregivers to help them understand the dying process. This involves not only viewing the caregiver as a coprovider of care to their dying loved one, but also evaluating the informal caregiver as a corecipient of care due to the enormous emotional, financial, and physical burdens associated with the caregiving role.48 In addition to viewing the informal caregiver as both a co-provider and a corecipient of care, an understanding of how the culture of care shapes the expectations of patients’ families is important for the provision of a supportive care environment. Understanding the culture of care is fundamental to the design and delivery of new models of care that stress the central importance of family-centered care mandated by the Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111–148).49 It is widely understood that “culture trumps strategy every time.”50(p1)

Acknowledgments

Funded through the National Institutes for Health, National Institute for Nursing Research, titled Exploring the Formal/Informal Caregiver Interface Across 3 Death Trajectories (NIH/NINR 5R01 NR01027-03). The project described was supported by Award Number R01NR010127 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The authors thank our clinical partners and family caregivers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

References

- 1.Holman H. Chronic disease: the need for a new clinical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1057–1059. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Care Continuum Alliance. Capitol Hill briefing to explore advances in chronic condition care. [Accessed January 10, 2011];Partnership Fight Chronic Dis. http://www.carecontinuum.org/news_releases/2009/pressrelease_012709.asp.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed January 10, 2011];Chronic diseases and health promotion. www.cdc.gov.

- 5.Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, Lloyd-Puyear MA, Strickland B, Trevathan E. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):407–412. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker JR, Crudder SO, Riske B, Bias V, Forsberg A. A model for a regional system of care to promote the health and well being of people with rare chronic genetic disorders. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11):1910–1916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.051318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowder BF. Improved symptom management through enrollment in an outpatient congestive heart failure clinic. Medsurg Nurs. 2006;15(1):27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul S. Impact of a nurse managed heart failure clinic: a pilot study. Am J Crit Care. 2000;9(2):140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducharme A, Doyon O, White M, Rouleau JL, Brophy J. Impact of care at a multidisciplinary congestive heart failure clinic: a randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(1):40–45. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akosah KO, Schaper AM, Haus LM, Mathiason MA, Barnhart SI, McHugh VL. Improving outcomes in heart failure in the community: long-term survival benefit of a disease management program. Chest. 2005;127(6):2042–2048. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akosah KO, Schaper AM, Havlik P, Barnhart S, Devine S. Improving care for patients with chronic heart failure in the community: the importance of a disease management program. Chest. 2002;122(3):906–912. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, Frost E, Hardiman O. Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study. 1996–2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1258–1261. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maizes V, Rakel D, Niemiec C. Integrative medicine and patient-centered care. Explore. 2009;5(5):277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seek AJ, Hogle WP. Modeling a better way: navigating the healthcare system for patients with lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(1):81–85. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vyt A. Interprofessional and transdisciplinary team-work in health care. Diabetes/Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(suppl 1):S106–S109. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osbourne H. In other words: communicating with people from other cultures. Health Literacy Consult; [Accessed October 4, 2010]. http://www.healthliteracy.com/article.asp?PageID=3821. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCluskey L, Casarett D, Siderowf A. Breaking the news: a survey of ALS patients and their caregivers. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 2004;5(3):131–135. doi: 10.1080/14660820410020772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozlowski SWJ, Ilgen DR. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2006;7(3):77–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiecha J, Pollard T. The interdisciplinary eHealth team: chronic care for the future. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhugra D, Popelyuk D, McMullen I. Paraphilias across cultures: contexts and controversies. J Sex Res. 2010;47(2/3):242–256. doi: 10.1080/00224491003699833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halbert CH, Barg FK, Weathers B, et al. Differences in cultural beliefs and values among African American and European American men with prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2007;14(3):277–284. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed October 29, 2010];Cultural competency. Clear Commun NIH Health Literacy Initiative. http://www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/culturalcompetency.htm.

- 23.Ovretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, et al. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Qual Safety Health Care. 2002;11:345–351. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strasser DC, Smits SJ, Falconer JA, Herrin JS, Bowen SE. The influence of hospital culture on rehabilitation team functioning in VA hospitals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39(1):115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponte PR, Peterson K. A patient- and family-centered care model paves the way for a culture of quality and safety. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20(4):451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update the growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. Issue Brief (AARP Public Policy Institute) 2011;51:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauser JM, Kramer BJ. Family caregivers in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levesque L, Ducharme F, Zarit S, Lachance L, Giroux F. Predicting longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in older husband caregivers: further analysis of existing data. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(3):333–342. doi: 10.1080/13607860801933414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life: “They don’t know what they don’t know. ” JAMA. 2004;291(4):483– 491. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weitzner MA, Haley WE, Chen H. The family care-giver of the older cancer patient. Hematol/Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14(1):269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding R, Higginson IJ. What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):63–74. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm667oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Smith A, Biddle B, Steis M. Understanding times of uncertainty: the end of life caregiving trajectory, variations of the caregiving trajectory: four illness trajectories, and the nursing imperative: intervening to support caregivers through times of uncertainty. In: Penrod J, editor. Family Caregivers: Living With Uncertainty Through the End of Life; Symposium conducted at the Sigma Theta Tau 38th Biennial Convention; November 2005; Indianapolis, IN. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Shipley PZ, Loeb SJ, Baney B. A model of caregiving through the end of life: seeking normal [published online ahead of print March 14, 2011] West J Nurs Res. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Time for Dying. Chicago: Aldine Publishing; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field M, Cassel C, editors. Report of the Institute of Medicine Task Force. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Baney B, Loeb S. End-of-life caregiving trajectories. Clin Nurs Res. doi: 10.1177/1054773810384852. [Published online ahead print September 27, 2010] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell JD, Borasio GD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2007;369:2031–2041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J, editors. SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: US SEER Program, 1988–2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; SEER Program, NIH Publication No. 07-6215;2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad H, Sra J, Levy W, Stapleton DD. Influence of predictive modeling in implementing optimal heart failure therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(3):185–190. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181ff2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lecompte M, Schensul J. Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goetz JP, LeCompte MD. Ethnographic research and the problem of data reduction. Anthropol Educ Q. 1981;12:51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, et al. Longitudinal analysis of multiple indicators of health decline among spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):101–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02883326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kay-Kyriacou C. Operationalizing the Concept of Moving Palliative Care Upstream [Abstract]. Proceedings of the Academy of Health Meeting; 2003; Nashville, TN. [Accessed June 15, 2011]. p. abstract no. 541. http://gateway.nlm.nih.gov/MeetingAbstracts/ma?f=102275514.html. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwekkeboom KA. Community needs assessment for palliative care services from a hospice organization. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):817–826. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibbon B, Watkins C, Barer D, et al. Can staff attitudes to team working in stroke care be improved? J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(1):105–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waldrop D, Kramer B, Skarteny J, Miltch R, Finn W. Final transitions: family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):623–632. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. no. 111–148, 124 STAT 120 (2010). Print.

- 50.Newman KP. Transforming organizational culture through nursing shared governance. Nurs Clin North Am. 2011;46(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]