Abstract

The purpose of this study is to illustrate variations in caregiving trajectories as described by informal family caregivers providing end-of-life care. Instrumental case study methodology is used to contrast the nature, course, and duration of the phases of caregiving across three distinct end-of-life trajectories: expected death trajectory, mixed death trajectory, and unexpected death trajectory. The sample includes informal family caregivers (n = 46) providing unpaid end-of-life care to others suffering varied conditions (e.g., cancer, organ failure, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). The unifying theme of end-of-life caregiving is “seeking normal” as family caregivers worked toward achieving a steady state, or sense of normal during their caregiving experiences. Distinct variations in the caregiving experience correspond to the death trajectory. Understanding caregiving trajectories that are manifest in typical cases encountered in clinical practice will guide nurses to better support informal caregivers as they traverse complex trajectories of end-of-life care.

Keywords: ALS, congestive heart failure, end of life, oncology

Dying takes time, and … health professionals, families and dying patients use many strategies to manage and shape the dying course.

(Corbin & Strauss, 1991, p. 157)

Introduction

The concept of trajectory evolved from seminal work on chronic illness and dying patients in the 1960s. In contrast to the course of an illness, the trajectory of an illness refers “not only to the physical unfolding of a disease, but to the total organization of work done over the course of the disease” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 20). Since then, the notion of trajectory has been applied to numerous illnesses, including stroke (Kirkevold, 2002), end-stage renal disease (Jablonski, 2004), cancer (Murray et al., 2007; Robinson, Nuamah, Cooley, & McCorkle, 1997), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Bremer, Simone, Walsh, Simmons, & Felgoise, 2004; Radunovic, Mitsumoto, & Leigh, 2007), and heart failure (Goldstein & Lynn, 2006; Gott et al., 2007; Hupcey, Penrod, & Fenstermacher, 2009). Trajectories of dying were first described by Glaser and Strauss (1968) and subsequently by Lunney and colleagues to include sudden death, terminal illness, organ failure, and frailty (Lunney, Lynn, Foley, Lipson, & Guralnik, 2003; Lunney, Lynn, & Hogan, 2002). This theoretical framing of illness and dying as complex, longitudinal experiences with recognizable phases promotes more coherent planning for service delivery.

Informal family caregivers provide significant contributions to end-of-life care, managing and shaping the experience of dying. Holistic family-centered care is an accepted goal of palliative care (e.g., see “Development of the NHPCO Research Agenda,” 2004; “Improving End-of-Life Care,” 2004; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2009); however, a comprehensive understanding of informal caregivers’ experiences over time, and across varied death trajectories, is lacking.

The stress process model developed by Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, and Skaff (1990) is one of the most commonly used frameworks for understanding end-of-life caregiving (Hauser & Kramer, 2004) and guiding intervention (Hebert, Arnold, & Schulz, 2007); however, from this perspective, the illness trajectory and progression of decline are most often obscured as background or contextual factors. For example, in Waldrop and colleagues’ (Waldrop, Kramer, Skretny, Milch, & Finn, 2005) study of end-stage caregiving, the illness/dying trajectory was subsumed as a background factor despite assertions that “the trajectory of each patient’s illness was individual and varied” (p. 630) and “fluctuations in the course of disease may initiate these functions at other times” (p. 634). Colclough and Young (2007) aptly conclude that most studies of end-of-life caregiving acknowledge the importance of the caregivers’ awareness of the critical nature of their charges’ condition and include themes related to the death of the care recipient, but not the dynamic caregiving processes that occur between those endpoints.

A more process-oriented approach was developed through a grounded theory study of informal family caregivers providing care through the end of life (Penrod, et. al., in review; Penrod, et. al., 2010). The core variable (or unifying theme) was seeking normal: in response to the changing care demands of advancing illness caregivers continually worked toward re-establishing a steady state, or a sense of pattern, amidst progressively changing care demands. The resultant trajectory of end-of-life caregiving consisted of four phases punctuated by three critical junctures or key transitions.

The caregiving trajectory is set into motion during the phase called Sensing a Disruption when the caregiver and/or the care recipient recognized a health problem. At the critical juncture of Confirming Suspicions, the disruption is labeled as a diagnosis of a life-threatening condition. As the caregivers come to terms with this diagnosis, the transition is abrupt; the old way of life, or steady state, is gone as they progress into the second phase of caregiving: Challenging Normal. In this phase, life focuses on new treatments and frequent healthcare appointments. The primary responsibility for directing the course of care is relinquished to the experts and caregivers take on the role of assistant while striving to retain some semblance of normal life. Yet again, caregivers take a dramatic turn as they describe coming to the realization that “there’s nothing more they can do.” This critical juncture, Acknowledging the End of Life, propels the caregiver into the third phase of the trajectory: Building a New Normal. Although sometimes guided by traditional end-of-life services (e.g., hospice), primary responsibility for decisions determining the course of comfort care shifts from the experts to the informal caregivers themselves in this phase of “active caregiving.” They focus on establishing a pattern of caring that, for most, is perceived to be “a 24 hour per day, 7 days per week” responsibility. The final critical juncture, Losing Normal, is when the death of the care recipient eradicates the established pattern of caring and launches the final phase of the caregiving trajectory: Reinventing Normal. During this time, the caregivers grieve their loss and begin to assemble a new pattern of normal, that is, life without the care recipient.

Whereas all caregivers reported experiencing all phases of the model, it was clear that the death trajectory of the care recipient shaped the course and duration of each of the phases, as illustrated in Table 1. The purpose of this article is to illustrate variations in the caregiving trajectory as described by informal family caregivers providing end-of-life care across three distinct death trajectories: expected (i.e., when death is anticipated due to a terminal diagnosis as in ALS), mixed (i.e., when early phases of the illness are aimed toward cure or stabilization, followed by a shift toward comfort care, as in traditional cancer models), and unexpected (i.e., when the illness is considered chronic, not terminal, as in heart failure). This baseline understanding of the experience of providing end-of-life care is essential to advancing theory-driven, research-based interventions to support these instrumental partners in care as they traverse through one of life’s most difficult experiences—the end of life.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Course and Duration of Three Death Trajectories

| Expected death trajectory | Mixed death trajectory | Unexpected death trajectory | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Course | Steep progressive decline, often measured in clinical benchmarks | Initial course of treatment/stability followed by sharp demarcation of steep terminal decline | Slow decline marked by exacerbations from which recovery never reaches former level of health |

| Duration of terminal phase | Prolonged from the point of diagnosis | Typically short | Extremely short |

Design

Instrumental case study methodology as described by Stake (1995) was used to examine patterned variations in end-of-life caregiving. Data were collected during the grounded theory study of end-of-life caregiving described above (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research R03 NRO8538). In order to describe variations in the caregiving trajectory corresponding to three distinct death trajectories, the richest cases, bound by the characteristics of the death trajectory of the care recipient, were selected as exemplars. Interpretations of the variations in the exemplars are then further explored in the Discussion section.

Sample

Adult providers of end-of-life caregiving were recruited from caregiver support groups, palliative care service providers, and a hospital-affiliated senior membership program. The final sample included 46 adult active or former caregivers (9 men and 37 women) providing supportive care for advanced cancers (52%); organ failure, including heart failure, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and renal failure (36%); ALS (10%); and frailty (2%). The majority of caregivers were spouses (64%). All of the male caregivers were spouses. Female caregivers included spouses and other familial relationships. The caregivers ranged in age from 36 to 84 years (mean age = 62 years), whereas the care recipients were slightly older (age range = 36–93 years, mean age = 71 years). These family members reported providing care for an average of 28 months from the time of diagnosis until death; however, variation in the length of caregiving was quite dramatic, ranging from a few weeks of intensive activity to years of progressively supportive care.

Data Collection

Prior to engaging participants for the study, the study was approved by a university-based institutional review board. All participants signed informed consent under principles of full disclosure. Face-to-face individual interviews (approximately 60–90 min) were the primary form of data collection. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then verified by the researchers to ensure accuracy of the data set. Initially, the interviews were unstructured using a broad, open-ended question to explore the phenomenon of caregiving at the end-of-life. Using unstructured interviews with nondirective prompts allowed each caregiver to tell her or his story, from the perceived beginning to the current state. Almost universally, the beginning was described as life before diagnosis. Both active and former caregivers were included in the sample, so the stories ended in times of advanced caregiving or early bereavement.

As an iterative process of data collection and analysis ensued interviews became more structured to advance a deeper understanding of the flow of caregiving over time. Participants were interviewed at least once; several participants were interviewed multiple times to extend a deeper understanding of the nature, course, and duration of phases of caregiving. The resultant data set included 46 discrete cases of end-of-life caregiving. At the conclusion of the data analysis, a group interview with multiple participants was used as a form of member checking to enhance the credibility of findings.

Analysis

The interview format and style permitted each participant to report a case of end-of-life caregiving. As data were collected, the analysis of the case studies began with categorical aggregation to establish categories or instances to reveal meaning in context. It became apparent that the death trajectory drove the caregiving experience—caregivers’ experiences pivoted on their anticipation of a sustained pattern of care, a sense of normal. Anticipating death dramatically shaped the experience. As these insights were clarified, categories were further analyzed to establish patterns and relationships in order to extend naturalistic interpretation or theoretical insights that promote a higher level of abstraction/ application. The case studies presented herein illustrate significant variations in course and duration of the phases of the caregiving trajectory across distinct death trajectories. Inconsequential descriptors have been altered to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Findings

Case Exemplar of Expected Death: The End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory of ALS

Mrs. G., aged 38, enjoyed a 14-year marriage that produced 4 children, and the youngest, a healthy infant. The preliminary phases of her husband’s illness, Sensing a Disruption, led to their suspicions being confirmed, thus launching the course of her caregiving trajectory:

He had some symptoms in 2000 [2 years before diagnosis], but we didn’t know what he had. He was just very weak and having trouble with the left side of his body, like his left leg and his left arm, and his speech was slurred. So we were making guesses of what it could have been. And he saw doctors, they kept saying, “Well, the blood work’s coming back normal and everything’s fine.” … We saw he was getting worse, and we knew something was seriously wrong with him. We went to a neurologist who diagnosed him and then after that he just progressively got worse and I started to care for him.

In the phase of Challenging Normal, Mrs. G. assumed a supportive role to her husband while attempting to maintain her everyday way of life.

I was always going downstairs to help … I was always down there. Up and down, up and down the steps ‘cause he was down in the family room downstairs, and it was one level so he could get his wheelchair in and out.”

The nature of the expected death trajectory enabled early discussions and anticipatory planning through Challenging Normal.

They [ALS clinic staff] were very helpful in educating us and helping us to know how to deal with things and kind of be ahead of it. Like, “Okay, soon this might happen so we need to get this in mind, to get this equipment.”

This education, a foreshadowing of things to come, affected the nature of the trajectory for Mrs. G. She understood the progressive deterioration of her husband, and, coupled with the known prognosis of ALS, her transition toward Acknowledging the End of Life was smoother.

I had an idea of what to expect—I knew when this time comes, then I knew this is what we could do. So I had ideas of how we could deal with that issue when it came up or if it came up. So I didn’t feel as helpless … at least I knew as it was happening, I thought, “Okay, you know that’s that.” And they gave us books to know, like as his swallowing gets worse, these are the foods you can feed him. So then I was ready. I didn’t have to wait for him to choke on something to know that, “Okay, we need to go to softer foods.” So we actually sometimes were ahead a little bit and say, “Well, it looks like you’re having a little trouble—I think we should switch now” or so, we at times we were able to be ahead of it before the problems.

Feeling “ahead of it” is indicative of her holding onto some form of normal by proactively planning for anticipated care issues. Yet escalating demands challenged that steady state, weighing heavily on Mrs. G. as she faced an escalated caregiving trajectory in the phase of Building a New Normal.

At first I was happy that I could help him, that he wanted me to help him. So I felt really good about that. And then as time went on I felt very tired all the time and stressed. I felt halfway. I felt so grateful that I could do stuff for him and the other half of me was like felt burdened and exhausted. … I always felt this pressure just inside like holding everything in and occasionally little spurts would come out whether it be crying or just you know losing my patience with the kids or other things. I kept telling myself, “You know you’re doing the best you can— at least he’s not in a nursing home, at least he’s not full time with somebody else.” I kept trying to pep myself up.

Despite being bolstered by an understanding of the progression of the disease, new caregiving demands upset the established routine, creating distress as she worked through Building a New Normal.

Caring for him wasn’t so bad ‘cause we learned the routine before his speech was gone. His speech was going gradually, but when his speech was gone that was the worst. If somebody’s ill and can’t move and can’t eat, and can’t drink— that’s one thing to care for that physical part. But when they can’t even tell you what they need and when it takes 20 minutes to figure it out, that’s the most frustrating thing. They feel helpless and you feel helpless. We tried spelling, but then the muscles in his eyes were weakening, so he couldn’t blink for the right letters and would get the letters mixed up. That was the most frustrating thing; not being able to communicate in the last weeks.

The entire caregiving trajectory lasted only 2 years, as her husband’s neurological function deteriorated until his death (i.e., Losing Normal). Mrs. G. describes her evolution toward Reinventing Normal approximately 18 months into bereavement.

I miss my husband, but I feel at peace. I feel I’m okay. I did what I knew what I could at the time, and I don’t beat myself up about it anymore. But when I think about it, I feel like I’m back over there again, but I know that I did the best that I could, and my husband did reassure me of that at times—so that was nice.

Case Exemplar of Mixed Death: The End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory of Terminal Cancer

Mrs. C., 56 years old, was 7 years into her second marriage with a blended family of college-age children when her husband began to experience symptoms described as indigestion. He sought medical advice and was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Mrs. C. described how Sensing a Disruption peaked at the critical juncture created when suspicions were confirmed.

It was just a real shocker. And then we went to [major medical center] for a little test [endoscopy], and that’s when we found out for sure. So that date is just like emblazoned into your memory.

Despite the seriousness of the diagnosis, the couple engaged in “hoping for the best” as they entered the phase of Challenging Normal.

He was still hopeful that the chemo and the surgery were gonna’ heal him. And this doctor had some pretty good results. There aren’t usually too many good results with pancreatic but [this doctor] had had some good results. … I ended up being the one who did all the driving for the next year and a half, looking for cures with him. I was torn up for that year and a half because he was progressively sicker with two major surgeries and having to deal with those nasty little drain things. And I said, “I’m not a nurse you know. I don’t want to do nasty things like that.” But, I did it all for him.

Through it all, Mrs. C. continued to work, altering her schedule to meet caregiving demands. She experienced a sense of looking for options in a fragmented system that ultimately dashed her hopes. This pattern was typical during the phase of Challenging Normal in the mixed trajectory.

It would just make me cry to think about the outcome, about what we were doing, about his losing his hair. And then every time during the illness, every time we would open a door, another one would slam in our faces. I mean nothing ever seemed to work. ‘Cause it’s a bad disease. And that’s what I mean when we always had little doors shut in our faces everywhere we went. “Oh you’re too far gone, we can’t do that.” There was always hope that kept getting dashed. Even though I knew that he was gonna’ die. I always had hope that he wouldn’t. And those were the uncertain times. You know you’d wait for the next time you could have a CAT scan and you’d wait, and wait, and wait.

She endured this rocky state of seeking normal until ominous signs led her to acknowledge that her husband’s end of life was imminent.

It just got so hard for him, and then in the last CAT scan we discovered it was in his lungs, and nothing was working. So I guess that’s when he finally stopped the chemo. All those things were big decisions.

Mrs. C. entered Building a New Normal as she assumed greater caregiving tasks with a new sense of responsibility. This phase lasted only 2 to 3 months, and hospice care was initiated.

That was the day he got his hospital bed and all that lovely stuff … the beginning of the end. It was just another two weeks. That’s when we really knew—it was just real difficult. The decision for him to accept hospice totally meant that I’m giving up, he’s giving up.

Two years following the death of her husband, Mrs. C. is still Reinventing Normal. She continues to fall asleep at night with the television on (a pattern held over from caregiving). She has gained weight and reports that feelings of guilt (“I should have done more”) still creep into her consciousness. She has resumed full-time work.

Case Exemplar of Unexpected Death: The End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory of Heart Failure

Mr. T., a 67-year-old, provided care to his wife of 43 years. About 10 years earlier, his wife had a severe heart attack, resulting in decompensated cardiac function. This event marked an abrupt beginning of Mr. T.’s caregiving trajectory with a significant disruption of normal; Mrs. T. was only 52 years old and had to quit her full-time job. This phase of Sensing a Disruption ended abruptly at the critical juncture of Confirming Suspicions, when the couple heard news that was not expected. The damage to her heart was not reversible, and it was permanent; she had heart failure. Over the initial course of the caregiving trajectory, Mr. T. described numerous challenges and attempts at sustaining Mrs. T.’s cardiac function. This is the reiterative nature of Challenging Normal in the unexpected death trajectory; each exacerbation or functional decline is accommodated, and a new steady state is established temporarily.

When she first came home from the hospital, she could hardly get around at all. Now, she can get around a little bit better and do a few things—her cardiologist told her that I would have to let her do more things. I don’t want her to be an invalid, but I don’t want her to overdo things. Like I do all the cleaning, the laundry too … she can make meals; I always help with the dishes.

The progressive decline was insidious. Despite decreased functional capacity progressing over 10 years and requiring numerous hospitalizations, Mr. T. described her last visit to the physician, “It hasn’t been real good but only because of all of this swelling. I don’t think her heart has changed. That is never going to change; that is not going to get better.” Throughout his in-depth discussion of his wife’s condition, Mr. T. frequently described this expectation of no improvement in her condition; however, he never anticipated the progressive nature of heart failure or the potential for sudden death. Mr. T. continued to work part-time during the night shift to able to provide care during the waking hours of the day.

Through these multiple iterations of Challenging Normal, Mrs. T. had cardiac catheterizations, several pacemaker/defibrillator implants, and increasingly complex regimens of medications. For Mr. T., Acknowledging the End of Life struck during a hospitalization when the cardiologist explained that “They were out of options.” In the 48 hours prior to her death, Mr. T.’s efforts at Building a New Normal were intense. He stayed at her bedside, comforting his wife and making the decision to forego intubation and resuscitation. He said, “There was nothing more we could do but keep her comfortable. I was right there with her when she died.” Mr. T. suffered the loss of his wife with profound grief; he was “shocked that we lost her.” His quest for Reinventing Normal has just begun.

Discussion

The most significant contribution of this work is illustration of common variations in end-of-life caregiving trajectories that are encountered in clinical practice. All caregivers in this sample reported theoretically congruent experiences of the phases of end-of-life caregiving; they all expressed times of Sensing a Disruption, Challenging Normal, Building a New Normal, and Reinventing Normal. Yet the course and duration of these phases across the trajectory of end-of-life caregiving varied in dynamic response to the death trajectory. The progression of the phases of end-of-life caregiving was predicated on the caregivers’ anticipation of death. Thus, three distinct end-of-life caregiving trajectories were identified in this work.

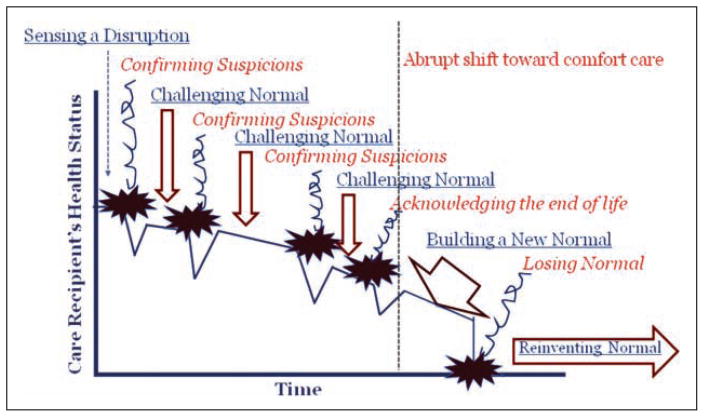

Expected Death End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory

As illustrated in Figure 1, although a terminal diagnosis is devastating, there is a degree of certainty regarding the illness/death trajectory. For example, in ALS, clearly distinguished clinical benchmarks mark the course of care from coming to terms with the diagnosis, through coping with impaired function, the end-of-life stage, and ultimately, after-death care for the family survivors (Raduvonic et al., 2007). Such in-depth understanding of the illness trajectory assists clinicians in planning the timing and delivery of services to support the person living with the terminal disease and the family (see Simmons, 2005).

Figure 1.

The expected end-of-life caregiving trajectory

Such anticipatory planning enables further support of the family caregiver as a co-provider and co-recipient of care. Anticipation of death opens the door for discussions of the expected nature of terminal decline and end-of-life preferences. The phase of Building a New Normal is prolonged as caregivers accept responsibility for comforting care through periods of marked functional decline. Care needs can be anticipated and services aligned for future initiation, pending the identification of a clinical benchmark. Since care is often delivered by a stable multidisciplinary team for these types of illnesses, there are greater opportunities for bolstering the family caregiver through difficult transitions of decline and loss.

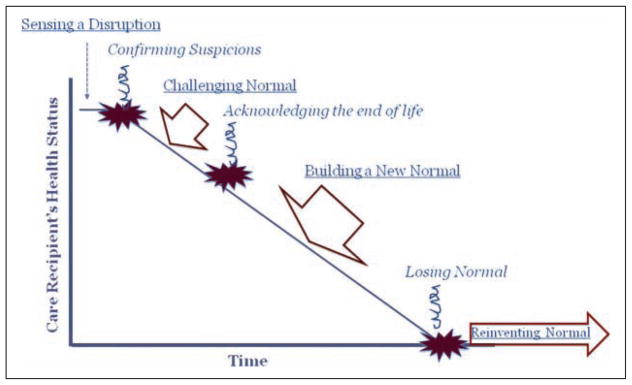

Mixed Death End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory

The traditional model of end-of-life care has been built around the illness/ death trajectory depicted in Figure 2. Consider the course of aggressive or advanced cancers. Early attempts at curative care or stabilization of disease are fierce. Families shift their priorities to accommodate whatever treatment, side effects, or appointment schedules are suggested. Then, at a clearly demarcated turning point, the focus of care shifts toward comfort over cure. This is an extremely difficult transition for family caregivers, as they feel dismissed by the experts and relegated to a new-found responsibility for managing supportive care for their dying loved one.

Figure 2.

The mixed death end-of-life caregiving trajectory

Thus, the label mixed death end-of-life caregiving trajectory: There is a mixed focus first on cure, then on care. During the focus on cure, death is held distant. This is a time when battle analogies often are used, “We will fight it,” or “We will hit it hard with all that we have.” At the shift toward comfort care, death comes into focus with harsh reality as hospice or other end-of-life care services are introduced. The war analogies end, and the focus becomes “keeping him comfortable.” In this study, family caregivers described an overwhelming sense of responsibility at the pivotal turning point when death became the expected outcome. For few, the accompanying shift in care delivery was seamless, but for most, the shift was more of a tearing away of the semblance of normal that was established. Sentiments of “giving up” or “giving in” were common.

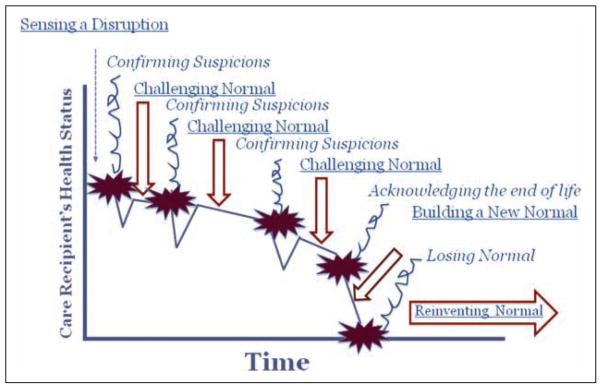

Unexpected Death End-of-Life Caregiving Trajectory

In contrast, as shown in Figure 3, the key characteristic of the unexpected end-of-life caregiving trajectory is the reiterative cycles of illness exacerbation and treatment during the phase described as Challenging Normal. Understanding the nature of these reiterative cycles provides a framework for interpreting the potential needs for palliative care, and ultimately hospice services, for this vulnerable population (e.g., see Goldstein & Lunn, 2006). This cyclical treatment and bounce-back predispose the caregiver to dwelling in the phase of Challenging Normal. During this phase, the informal caregiver centers on following doctors’ orders and promptly identifying changes in condition that warrant prompt attention. There is no anticipation of death, only of the potential for an exacerbation requiring another form of intervention. Family caregivers follow the flow of illness, without forethought of the likelihood of significant functional decline and death.

Figure 3.

The unexpected end-of-life caregiving trajectory

More recently, a relatively wide range of individual variation in the illness/ death trajectory of heart failure has been documented (Gott et al., 2007), prompting assertions that a one-size-fits-all approach to planning advanced illness/end-of-life services is not advisable for heart failure. In response, Hupcey and colleagues (2009) have proposed an alternative model of anticipatory palliative care that is highly individualized. From a caregiving perspective, anticipatory palliative care implies a philosophical shift that embraces a more realistic attitude toward the likelihood of death and, potentially, an earlier shift into the phase described as Building a New Normal. In this study, caregivers who experienced a prolonged phase of Building a New Normal expressed having time to tie up loose ends and say good-bye; thus, this philosophical shift may enable smoother transitions for informal family caregivers.

Application

Although three illnesses trajectories are cited in these exemplars, the caregiving trajectories are not disease driven. Rather, consideration of the anticipation of death is a key characteristic of the caregiving trajectory. Is death expected, unexpected, or mixed? For example, Schubart, Kinzie, and Farace (2008) in their description of caregiving in response to brain tumor histology note that the illness trajectory of aggressive glioblastoma is markedly different than that for a tumor of less aggressive histology; therefore, the family caregiver may face an expected or a mixed trajectory of end-of-life care. It is not the diagnosis of cancer that predicates the end-of-life caregiving trajectory; it is the anticipation of death. Similarly, although caregiving across the trajectory of frailty (as described by Lunney et al., 2002) was not examined in this study, this protracted trajectory of caregiving warrants further investigation from the perspective of end-of-life care.

It is imperative that nurses embrace informal family caregivers as both co-providers and co-recipients of care. Nurses are instrumental partners in caregiving, especially as they share their understanding of illness trajectories, interpreting the course of an illness and related functional changes. This type of knowledge builds the informal family caregiver as co-providers of care. For example, nurses teach family members how to measure weights accurately in order to titrate diuretics for those with heart failure. Families are taught how to maintain adequate nutrition when the side effects of cancer treatments emerge. Caregiv-ers of ALS learn how to lift, turn, and use assistive devices. The findings of this study provide a platform for nurses to embrace family caregivers as co-recipients of care. Understanding the transitions and major concerns of family caregivers enables nurses to more anticipate the challenges and demands of caregiving, emphasizing a pervasive quest for a sense of normal.

Informal caregivers have expressed a desire for strong, supportive relationships with their health care providers (Steinhauser, Christakis, & Clippo, 2000). Within these relationships, providers, particularly nurses, are able to support informal caregivers through difficult transitions (Meleis & Trangenstein, 1994). For example, this study revealed that across each trajectory, transitions in care introduced caregivers to multiple settings and specialists, challenging whatever steady state (or normal) had been achieved. Transitions are difficult, stressful times of disrupted normal (Schubart et al., 2008). Coordination of care is critical, and often, nurses are at the forefront of the hand-offs between settings and specialists. Repeated descriptions of discontinuity and fragmented care systems in this study were disheartening, something also observed by Jo, Brazil, Lohfeld, and Willison (2007). Nurses emerged as the caregivers’ anchors across care settings encountered throughout the trajectory—we must attend to this critically important role.

Nurses hold tremendous power in shaping informal caregivers’ experiences as co-providers of care. We must now move toward exerting such influence in embracing informal caregivers as co-recipients of care by advancing theory-driven, research-based interventions. Understanding the caregiving trajectory and variations across distinct death trajectories provides a framework for translating supportive interventions for caregivers living through one of life’s most difficult transitions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge our clinical partners and family caregivers who participated in this study.

Funding

The project described was supported by Grant Number R03 NR08538 from September 2003–August 2005. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Biographies

Janice Penrod, PhD, RN, is an associate professor of nursing, School of Nursing, and of humanities, College of Medicine, the Pennsylvania State University, University Park and Hershey, PA.

Judith E. Hupcey, EdD, CRNP, is an associate professor of nursing, School of Nursing, and of medicine, College of Medicine, the Pennsylvania State University, University Park and Hershey, PA.

Brenda L. Baney, BS, is a research assistant, School of Nursing, the Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Susan J. Loeb, PhD, RN, is an associate professor of nursing, School of Nursing, and of medicine, College of Medicine, the Pennsylvania State University, University Park and Hershey, PA.

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bremer BA, Simone AL, Walsh S, Simmons Z, Felgoise SH. Factors supporting quality of life over time for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The role of positive self-perception and religiosity. Annals of Behavior Medicine. 2004;28(2):119–125. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colclough YY, Young HM. Decision making at end of life among Japanese American families. Journal of Family Nursing. 2007;13:201–225. doi: 10.1177/1074840707300761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, Strauss A. A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the Trajectory Framework. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1991;5:155–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development of the NHPCO research agenda. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;28(5):488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Time for dying. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NE, Lynn J. Trajectory of end-stage heart failure: The influence of technology and implications for policy change. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2006;49(1):10–18. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2006.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C, Payne S, Seamark D, Gariballa S, et al. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21(2):95–99. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser JM, Kramer BJ. Family caregivers in palliative care. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2004;20:671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert RS, Arnold RM, Schulz R. Improving well-being in caregivers of terminally ill patients. Making the case for patient suffering as a focus for intervention research. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fenstermacher K. Review article: A model of palliative care for heart failure. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2009;26:399–404. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving End-of-Life care. National Institutes of Health Consensus State of Science Statements. 2004;21(3):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski A. The illness trajectory of end-stage renal disease dialysis patients. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2004;18(1):51–72. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.18.1.51.28053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, Willison K. Caregiving at the end of life: Perspectives from spousal caregivers and care recipients. Palliative Supportive Care. 2007;5(1):11–7. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkevold M. The unfolding illness trajectory of stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002;24:887–898. doi: 10.1080/09638280210142239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older Medicare decedents. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2002;50:1108–1112. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI, Trangenstein PA. Facilitating transitions: Redefinition of a nursing mission. Nursing Outlook. 1994;42:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0029-6554(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (2) 2009 Available from http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org.

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Shipley P, Loeb SJ, Baney B. Seeking normal: A model of caregiving through the end of life. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400920. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Loeb SJ, Spigelmyer P, Shipley P, Baney B. Supporting Family Care giver through End-of-Life Transitions: Opened Doors and Missed Opportunities. In: Penrod J, editor. Symposium conducted at the Eastern Nursing Research Society 22nd Annual Scientific Sessions; Providence, RI. 2010. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Radunovic A, Mitsumoto H, Leigh PN. Clinical care of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurology. 2007;6:913–925. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L, Nuamah IF, Cooley ME, McCorkle R. A test of the fit between the Corbin and Strauss Trajectory Model and care provided to older patients after cancer surgery. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1997;12(1):36–47. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199710000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: Family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10(1):61–72. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons Z. Management strategies for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from diagnosis through death. Neurologist. 2005;11:257–270. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000178758.30374.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis MA, Clippo EC. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop DP, Kramer BJ, Skretny JA, Milch RA, Finn W. Final transitions: Family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:623–638. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener CL, Dodd MJ. Coping amid uncertainty: An illness trajectory perspective. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1993;7:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]