Abstract

Objective

Recent studies have demonstrated that genetic polymorphisms near the IL28B gene are associated with the clinical outcome of pegylated interferon α (peg-IFN-α) plus ribavirin therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, it is unclear whether genetic variations near the IL28B gene influence hepatic interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene (ISG) induction or cellular immune responses, lead to the viral reduction during IFN treatment.

Design

Changes in HCV-RNA levels before therapy, at day 1 and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 after administering peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin were measured in 54 patients infected with HCV genotype 1. Furthermore, we prepared four lines of chimeric mice having four different lots of human hepatocytes containing various single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) around the IL28B gene. HCV infecting chimeric mice were subcutaneously administered with peg-IFN-α for 2 weeks.

Results

There were significant differences in the reduction of HCV-RNA levels after peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy based on the IL28B SNP rs8099917 between TT (favourable) and TG/GG (unfavourable) genotypes in patients; the first-phase viral decline slope per day and second-phase slope per week in TT genotype were significantly higher than in TG/GG genotype. On peg-IFN-α administration to chimeric mice, however, no significant difference in the median reduction of HCV-RNA levels and the induction of antiviral ISG was observed between favourable and unfavourable human hepatocyte genotypes.

Conclusions

As chimeric mice have the characteristic of immunodeficiency, the response to peg-IFN-α associated with the variation in IL28B alleles in chronic HCV patients would be composed of the intact immune system.

Keywords: HCV, Antiviral Therapy, Genetic Polymorphisms, Interferon, Liver Immunology

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Genetic polymorphisms near the IL28B gene are associated with a chronic HCV treatment response.

HCV-infected patients with the IL28B homozygous favourable allele had a more rapid decline in HCV kinetics in the first and second phases by peg-IFN-α-based therapy.

During the acute phase of HCV infection, a strong immune response among patients with the IL28B favourable genotype could induce more frequent spontaneous clearance of HCV.

What are the new findings?

In chronically HCV genotype 1b-infected chimeric mice that have the characteristic of immunodeficiency, no significant difference in the reduction in serum HCV-RNA levels and the induction of antiviral hepatic ISG by the administration of peg-IFN-α was observed between favourable and unfavourable human hepatocyte IL28B genotypes.

By comparison of serum HCV kinetics between human and chimeric mice, the viral decline in both the first and second phases by peg-IFN-α treatment was affected by the variation in IL28B genotypes only in chronic hepatitis C patients.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The immune response according to IL28B genetic variants could contribute to the first and second phases of HCV-RNA decline and might be critical for HCV clearance by peg-IFN-α-based therapy.

Introduction

Hepatitis C is a global health problem that affects a significant portion of the world's population. The WHO estimated that, in 1999, 170 million hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients were present worldwide, with 3–4 million new cases appearing per year.1

The standard therapy for hepatitis C still consists of pegylated interferon-α (peg-IFN-α), administered once weekly, plus daily oral ribavirin for 24–48 weeks in countries where protease inhibitors are not available.2 This combination therapy is quite successful in patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 infection, leading to a sustained virological response (SVR) in approximately 80–90% of patients treated; however, in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4, only approximately half of all treated individuals achieved a SVR.3 4

Host factors were shown to be associated with the outcome of the therapy, including age, sex, race, liver fibrosis and obesity.5 Genome-wide association studies have demonstrated that genetic variations in the region near the interleukin-28B (IL28B) gene, which encodes interferon (IFN)-λ3, are associated with a chronic HCV treatment response.6–10 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that genetic variations in the IL28B gene region are also associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.11–12

Interestingly, a recent report showed the effect of genetic polymorphisms near the IL28B gene on the dynamics of HCV during peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy in Caucasian, African American and Hispanic individuals;13 HCV-infected patients with the IL28B homozygous favourable allele had a more rapid decline of HCV in the first phase, which is associated with the inhibition of viral replication as well as the second phase associated with immuno-destruction of viral-infected hepatocytes.14 However, it is unknown how a direct effect by the IL28B genetic variation, such as the induction of IFN-stimulated genes (ISG) or cellular immune responses, would influence the viral kinetics during IFN treatment. Over recent periods, engineered severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice transgenic for urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) received human hepatocyte transplants (hereafter referred to as chimeric mice)15–17 and are suitable for experiments with hepatitis viruses in vivo.18 19 We have also reported that these chimeric mice carrying human hepatocytes are a robust animal model to evaluate the efficacy of IFN and other anti-HCV agents.20 21

The purpose of this study was to reveal the association between genetic variations in the IL28B gene region and viral decline during peg-IFN-α treatment in patients with HCV, and to clarify the association between different IL28B alleles of human hepatocytes in chimeric mice and the response to peg-IFN-α without immune response. These studies will elucidate whether the immune response by the IL28B genetic variation affects the viral kinetics during peg-IFN-α treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients

Fifty-four Japanese patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection at Nagasaki Medical Center and Nagoya City University were enrolled in this study (table 1). Patients received peg-IFN-α2a (180 μg) or 2b (1.5 μg/kg) subcutaneously every week and were administered a weight-adjusted dose of ribavirin (600 mg for <60 kg, 800 mg for 60–80 kg, and 1000 mg for >80 kg daily), which is the recommended dosage in Japan. Patients with other hepatitis virus infection or HIV coinfection were not included in the study. The study protocol conformed to the ethics guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected by earlier approval by the institutions’ human research committees.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 54 patients infected HCV genotype 1

| IL28B SNP rs8099917 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TT (n=34) | TG (n=19) + GG (n=1) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 55.6±10.1 | 54.7±11.3 | 0.746 |

| Gender (male %) | 70 | 50 | 0.199 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.6±3.1 | 24.7±3.3 | 0.870 |

| Viral load at therapy (log IU/ml) | 6.0±0.7 | 5.8±0.8 | 0.357 |

| SVR rate (%) | 50 | 11 | 0.012 |

| Serum ALT level (IU/l) | 100.3±80.8 | 79.3±45.0 | 0.226 |

| Platelet count (×104/μl) | 17.1±9.0 | 16.5±5.8 | 0.771 |

| Fibrosis (F3+4 %) | 42 | 40 | 0.877 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SVR, sustained virological response.

Laboratory tests

Blood samples were obtained before therapy, as well as on day 1 and at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 after the start of therapy and were analysed for the HCV-RNA level by the commercial Abbott Real-Time HCV test with a lower limit of detection of 12 IU/ml (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plains, Illinois, USA). Genetic polymorphism in the IL28B gene (rs8099917), a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) recently identified to be associated with treatment response,6–8 was tested by the TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA).

HCV infection of chimeric mice with the liver repopulated for human hepatocytes

SCID mice carrying the uPA transgene controlled by an albumin promoter were injected with 5.0–7.5×105 viable hepatocytes through a small left-flank incision into the inferior splenic pole, thereafter chimeric mice were generated. The chimeric mice were purchased from PhoenixBio Co, Ltd (Hiroshima, Japan).17 Human hepatocytes with the IL28B homozygous favourable allele, heterozygous allele or homozygous unfavourable allele were imported from BD Biosciences (San Jose, California, USA) (table 2). Murine serum levels of human albumin and the body weight were not significantly different among four chimeric mice groups, providing a reliable comparison for anti-HCV agents.22 Three different serum samples were obtained from three chronic HCV patients (genotype 1b).21 22 Each mouse was intravenously infected with serum sample containing 105 copies of HCV genotype 1b. Administration of peg-IFN-α2a (Pegasys; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at the dose formulation (30 μg/kg) was consecutively applied to each mouse on days 0, 3, 7 and 10 (table 3).

Table 2.

Four lines of uPA/SCID mice from four different lots of human hepatocytes (donor) containing various SNP around the IL28B gene

| uPA/SCID mice | Donor | Race | Age | Gender | rs8103142 | rs12979860 | rs8099917 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PXB mice | A | African American | 5 Years | Male | CC | TT | TG |

| B | Caucasian | 10 Years | Female | CC | TT | TG | |

| C | Hispanic | 2 Years | Female | TT | CC | TT | |

| D | Caucasian | 2 Years | Male | TT | CC | TT |

PXB mice; urokinase-type plasminogen activator/severe combined immunodeficiency (uPA/SCID) mice repopulated with approximately 80% human hepatocytes.

SCID, severe combined immunodeficient; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 3.

Dosage and time schedule of pegIFN-α2a* treatment for HCV genotype 1b infected chimeric mice

| Dose | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor hepatocytes† | No of chimeric mice | Inoculum | Test compound | Level (μg/kg) | Concentrtion (μg/ml) | Volume (ml/kg) | Frequency |

| A | 3 | Serum A | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| B | 4 | Serum A | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| C | 3 | Serum A | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| D | 3 | Serum A | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| A | 2 | Serum B | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| C | 2 | Serum B | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| A | 2 | Serum C | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

| C | 2 | Serum C | Peg-IFN-α2a | 30 | 3 | 10 | Day 0, 3, 7, 10 |

*Pegasys; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

†The IL28B genetic variation of the donor hepatocytes was indicated in table 2.

HCV, hepatitis C virus; peg-IFN-α, pegylated interferon α.

HCV-RNA quantification

HCV-RNA in mice sera (days 0, 1, 3, 7 and 14) was quantified by an in-house real-time detection PCR assay with a lower quantitative limit of detection of 10 copies/assay, as previously reported.21

Quantification of IFN-stimulated gene-expression levels

For analysis of endogenous ISG levels, total RNA was isolated from the liver using the RNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA) and complementary DNA synthesis was performed using 2.0 µg of total RNA (High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit; Applied Biosystems). Fluorescence real-time PCR analysis was performed using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan Fast Advanced gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primer and probe sets (Applied Biosystems) are shown in the supplementary information (available online only). Relative amounts of messenger RNA, determined using a FAM-Labeled TaqMan probe, were normalised to the endogenous RNA levels of the housekeeping reference gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The delta Ct method (2−(delta Ct)) was used for quantitation of relative mRNA levels and fold induction.23 24

Statistical analyses

Statistical differences were evaluated by Fisher's exact test or the χ2 test with the Yates correction. Mice serum HCV-RNA and intrahepatic ISG expression levels were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant if p values were less than 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the study patients

Genotypes (rs8099917) TT, TG and GG were detected in 34, 19 and one patient infected with HCV genotype 1, respectively. SVR rates were significantly higher in HCV patients with genotype TT than in those with genotype TG/GG (50% vs 11%, p=0.012). The initial HCV serum load was comparable between genotypes TT and TG/GG (6.0±0.7 vs 5.8±0.8 log IU/ml). There were no significant differences in sex (male%, 70% vs 50%), age (55.6±10.1 vs 54.7±11.3 years), serum alanine aminotransferase level (100.3±80.8 vs 79.3±45.0 IU/L), platelet count (17.1±9.0 vs 16.5±5.8×104/μl) and fibrosis stages (F3/4%, 42% vs 40%) between HCV patients with the favourable (rs8099917 TT) and unfavourable (rs8099917 TG/GG) IL28B genotypes (table 1).

Changes in serum HCV-RNA levels in patients treated by peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin

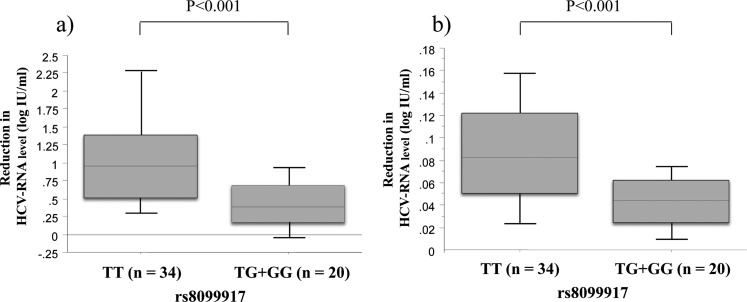

Figure 1 shows the initial change in the serum HCV-RNA level for 14 days after peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 based on the genetic polymorphism near the IL28B gene. The immediate antiviral response (viral drop 24 h after the first IFN injection) was significantly higher in HCV patients with genotype TT than genotype TG/GG (−1.08 vs −0.39 log IU/ml, p<0.001). Figure 2 also shows the subsequent change in the serum HCV-RNA reduction after peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. Similarly, during peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy, a statistically significant difference in the median reduction in serum HCV-RNA levels was noted according to the genotype (TT vs TG/GG). The median reduction in the serum HCV-RNA levels (log IU/ml) at 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks between genotypes TT and TG/GG was as follows: −1.58 vs −0.62, p<0.001; −2.35 vs −0.91, p<0.001; −3.48 vs −1.56, p<0.001; −4.53 vs −2.37, p<0.01; −4.93 vs −2.86, p<0.001. Furthermore, the initial first-phase viral decline slope per day (Ph1/day) and subsequent second-phase viral decline slope per week (Ph2/week) in TT genotype were significantly higher than in genotype TG/GG (Ph1/day 0.94±0.83 vs 0.38±0.40 log IU/ml, p<0.001; Ph2/week 0.08±0.06 vs 0.04±0.03 log IU/ml, p<0.001) (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Rapid reduction of median hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA levels (log IU/ml) at 1, 7 and 14 days between IL28B single nucleotide polymorphisms rs8099917 genotype TT (n=34) and TG/GG (n=20) in HCV genotype 1-infected patients treated with peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin.

Figure 2.

Weekly reduction of median hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA levels (log IU/ml) at 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks between IL28B single nucleotide polymorphisms rs8099917 genotype TT (n=34) and TG/GG (n=20) in HCV genotype 1-infected patients treated with pegylated interferon α plus ribavirin.

Figure 3.

(A) The first-phase viral decline slope per day (Ph1/day) and (B) second-phase viral decline slope per week (Ph2/week) in hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1-infected patients treated with pegylated interferon α plus ribavirin. The lines across the boxes indicate the median values. The hash marks above and below the boxes indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles for each group, respectively.

Changes in serum HCV-RNA levels in chimeric mice treated by peg-IFN-α

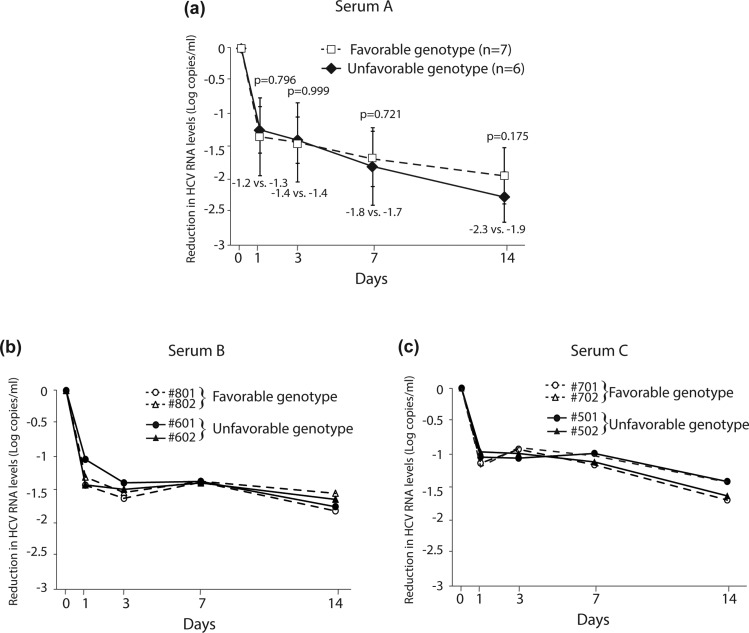

In order to clarify the association between IL28B alleles of human hepatocytes and the response to peg-IFN-α, we prepared four lines of uPA/SCID mice and four different lots of human hepatocytes containing various rs8099917, rs8103142 and rs12979860 SNPs around the IL28B gene (table 2). The chimeric mice were inoculated with serum samples from each HCV-1b patient, and then HCV-RNA levels had increased and reached more than 106 copies/ml in all chimeric mice sera at 2 weeks after inoculation. After confirming the peak of HCV-RNA in all chimeric mice, they were subcutaneously administered with four times injections of the bolus dose of peg-IFN-α2a for 2 weeks (table 3). Figure 4 shows the change in the serum HCV-RNA levels for 14 days during IFN injection into chimeric mice transplanted with IL28B favourable or unfavourable human hepatocyte genotypes. On peg-IFN-α administration, no significant difference in the median reduction in HCV-RNA levels in the serum A-infected22 chimeric mice sera was observed between favourable (n=7) and unfavourable (n=6) IL28B genotypes on days 1, 3, 7 and 14 (−1.2 vs −1.3, −1.4 vs −1.4, −1.8 vs −1.7, and −2.3 vs −1.9 log copies/ml) (figure 4A). Moreover, we prepared two additional serum samples from the other HCV-1b patients (serum B and C)21 to confirm the influence of IL28B genotype in early viral kinetics during IFN treatment. After establishing persistent infection with new HCV-1b strains in all chimeric mice, they were also administered four times injections of the bolus dose of peg-IFN-α2a for 2 weeks (figure 4B,C). In a similar fashion, no significant difference in HCV-RNA reduction in chimeric mice sera was observed between favourable and unfavourable IL28B genotypes.

Figure 4.

Median reduction of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA levels (log copies/ml) after administering pegylated interferon α to chimeric mice having human hepatocytes containing various single nucleotide polymorphisms around the IL28B gene as favourable (rs8099917 TT) and unfavourable (rs8099917 TG) genotypes. Data are represented as mean+SD. Chimeric mice infected with a) serum A (n=7; favourable genotype, n=6; unfavourable genotype), (B) serum B (n=2, each genotype), and (C) serum C (n=2, each genotype). All serum samples were obtained from HCV-1b patients.

Expression levels of ISG in chimeric mice livers

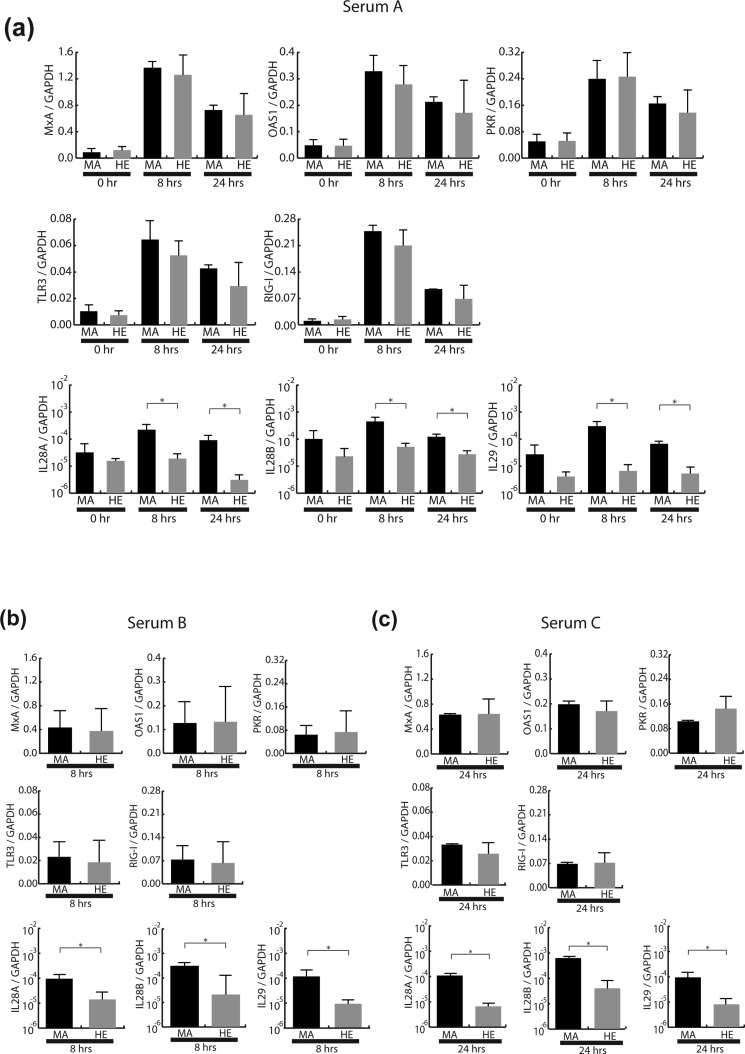

Because chimeric mice have the characteristic of severe combined immunodeficiency, the viral kinetics in chimeric mice sera during IFN treatment could be contributed by the innate immune response of HCV-infected human hepatocytes. Therefore, ISG expression levels in mice livers transplanted with human hepatocytes were compared between favourable and unfavourable IL28B genotypes (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Intrahepatic interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene (ISG) expression levels in the pegylated interferon α (peg-IFN-α)-treated chimeric mice having human hepatocytes containing homozygous favourable allele (rs8099917 TT; MA) and heterozygous unfavourable allele (rs8099917 TG; HE) were measured and expressed relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA. Data are represented as mean+SD. (A) Time kinetics of ISG after administration of the peg-IFN-α in serum A-infected chimeric mice (n=3, each genotype). Comparison of ISG expression levels at (B) 8 h in serum B-infected mice and (C) 24 h in serum C-infected mice after administering peg-IFN-α (n=3, each genotype). Predesigned real-time PCR assay of IL28B transcript purchased from Applied Biosystems can be cross-reactive to IL28A transcript. *p<0.05. MxA, myxovirus resistance protein A; OAS1, oligoadenylate synthetase 1; PKR, RNA-dependent protein kinase; RIG-1, retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; TLR3, Toll-like receptor 3.

As shown in figure 5A, ISG expression levels in mice livers were measured at 8 h and 24 h after IFN treatment. The levels of representative antiviral ISG (eg, myxovirus resistance protein A, oligoadenylate synthetase 1, RNA-dependent protein kinase) and other ISG for promoting antiviral signalling (eg, Toll-like receptor 3, retinoic acid-inducible gene 1) were significantly induced at least 8 h after treatment, and prolonged at 24 h. No significant difference in ISG expression levels in HCV-infected livers was observed between favourable and unfavourable IL28B genotypes. The other inoculum for persistent infection of HCV-1b also demonstrated no significant difference in ISG expression levels between favourable and unfavourable IL28B genotypes (figure 5B,C). Interestingly, IFN-λ expression levels by treatment of peg-IFN-α were significantly induced in HCV-infected human hepatocytes harbouring the favourable IL28B genotype (figure 5 A–C).

Discussion

Several recent studies have demonstrated a marked association between the chronic hepatitis C treatment response6–9 and SNP (rs8099917, rs8103142 and rs12979860) near or within the region of the IL28B gene, which affected the viral dynamics during peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy in Caucasian, African American and Hispanic individuals.13

It has been reported that when patients with chronic hepatitis C are treated by IFN-α or peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin, HCV-RNA generally declines after a 7–10 h delay.25 The typical decline is biphasic and consists of a rapid first phase lasting for approximately 1–2 days during which HCV-RNA may fall 1–2 logs in patients infected with genotype 1, and subsequently a slower second phase of HCV-RNA decline.26 The viral kinetics had a predictive value in evaluating antiviral efficacy.14 In this study, biphasic decline of the HCV-RNA level during peg-IFN-α treatment was observed in both patients and chimeric mice infected with HCV genotype 1; however, in the first and second phases of viral kinetics, a difference between IL28B genotypes was observed only in HCV-infected patients; a more rapid decline in serum HCV-RNA levels after administering peg-IFN-α plus ribavirin was confirmed in patients with the TT genotype of rs8099917 compared to those with the TG/GG genotype.

On the other hand, in-vivo data using the chimeric mouse model showed no significant difference in the reduction of HCV-RNA titers in mouse serum among four different lots of human hepatocytes containing IL28B favourable (rs8099917 TT) or unfavourable (rs8099917 TG) genotypes, which was confirmed by the inoculation of two additional HCV strains. These results indicated that variants of the IL28B gene in donor hepatocytes had no influence on the response to peg-IFN-α under immunosuppressive conditions, suggesting that the immune response according to IL28B genetic variants could contribute to the first and second phases of HCV-RNA decline and might be critical for HCV clearance by peg-IFN-α-based therapy.

Two recent studies indeed revealed an association between the IL28B genotype and the expression level of hepatic ISG in human studies.27 28 Quiescent hepatic ISG before treatment among patients with the IL28B favourable genotype have been associated with sensitivity to exogenous IFN treatment and viral eradication; however, it is difficult to establish whether the hepatic ISG expression level contributes to viral clearance independently or appears as a direct consequence of the IL28B genotype. Another recent study addressed this question and the results suggested that there is no absolute correlation with the IL28B genotype and hepatic expression of ISG.29 Our results on the hepatic ISG expression level in immunodeficient chimeric mice also suggested that no significant difference in ISG expression levels was observed between favourable and unfavourable IL28B genotypes. However, these results were not consistent with a previous report using chimeric mice that the favourable IL28B genotype was associated with an early reduction in HCV-RNA by ISG induction.30 The reasons for the discrepancy might depend on the dose and type of IFN treatment, as well as the time point when ISG expression was examined in the liver. In addition, although IFN-λ transcript levels measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells or liver revealed inconsistent results in the context of an association with the IL28B genotype,7 8 our preliminary assay on the IL28A, IL28B and IL29 transcripts in the liver first indicated that the induction of IFN-λ on peg-IFN-α administration could be associated with the IL28B genotype. Therefore, the induction of IFN-λ followed by immune response might contribute to different viral kinetics and treatment outcomes in HCV-infected patients, because no difference was found in chimeric mice without immune response.

It has also been reported that the mechanism of the association of genetic variations in the IL28B gene and spontaneous clearance of HCV may be related to the host innate immune response.11 Interestingly, participants with seroconversion illness with jaundice were more frequently rs8099917 homozygous favourable allele (TT) than other genotypes (32% vs 5%, p=0.047). This suggests that a stronger immune response during the acute phase of HCV infection among patients with the IL28B favourable genotype would induce more frequent spontaneous clearance of HCV.

Taking into account both the above results in acute HCV infection and our results conducted on chimeric mice that have the characteristic of immunodeficiency, it is suggested that the response to peg-IFN-α associated with the variation in IL28B alleles in chronic hepatitis C patients would be composed of the intact immune system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kyoko Ito of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Nagoya, Japan for doing the quantification of gene-expression assays.

Footnotes

Contributors: YT and MM conceived the study. TW and FS and YT conducted the study equally. TW and FS coordinated the analysis and manuscript preparation. All the authors had input into the study design, patient recruitment and management or mouse management and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. TW, FS and YT contributed equally.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (H22-kannen-005) and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and grant-in-aid for research in Nagoya City University.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of each ethics committee at the Nagoya City University and Nagasaki Medical Center (see supplementary information, available online only).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ray Kim W. Global epidemiology and burden of hepatitis C. Microbes Infect 2002;4:1219–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster GR. Past, present, and future hepatitis C treatments. Semin Liver Dis 2004;24(Suppl. 2):97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:958–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihm U, Herrmann E, Sarrazin C, et al. Review article: predicting response in hepatitis C virus therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:1043–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009;461:399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009;41:1100–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M,et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet 2009;41:1105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1338–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, et al. lambda-Interferons and the single nucleotide polymorphisms: a milestone to tailor-made therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res 2010;40:449–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 2009;461:798–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grebely J, Petoumenos K, Hellard M, et al. Potential role for interleukin-28B genotype in treatment decision-making in recent hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2010;52:1216–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology 2010;139:120–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layden-Almer JE, Layden TJ. Viral kinetics in hepatitis C virus: special patient populations. Semin Liver Dis 2003;23(Suppl. 1):29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckel JL, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, et al. Neonatal bleeding in transgenic mice expressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Cell 1990;62:447–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhim JA, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, et al. Replacement of diseased mouse liver by hepatic cell transplantation. Science 1994;263:1149–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tateno C, Yoshizane Y, Saito N, et al. Near completely humanized liver in mice shows human-type metabolic responses to drugs. Am J Pathol 2004;165:901–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercer DF, Schiller DE, Elliott JF, et al. Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat Med 2001;7:927–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuge M, Hiraga N, Takaishi H, et al. Infection of human hepatocyte chimeric mouse with genetically engineered hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 2005;42:1046–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Chub E, et al. Molecular epidemiology and interferon susceptibility of the natural recombinant hepatitis C virus strain RF1_2k/1b. J Infect Dis 2008;198:1448–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Matsuura K, et al. Positive selection of core 70Q variant genotype 1b hepatitis C virus strains induced by pegylated interferon and ribavirin. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1663–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue K, Umehara T, Ruegg UT, et al. Evaluation of a cyclophilin inhibitor in hepatitis C virus-infected chimeric mice in vivo. Hepatology 2007;45:921–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001;25:402–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silver N, Best S, Jiang J, et al. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol 2006;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahari H, Layden-Almer JE, Perelson AS, et al. Hepatitis C viral kinetics in special populations. Curr Hepat Rep 2008;7:97–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 1998;282:103–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honda M, Sakai A, Yamashita T, et al. Hepatic ISG expression is associated with genetic variation in interleukin 28B and the outcome of IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2010;139:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urban TJ, Thompson AJ, Bradrick SS, et al. IL28B genotype is associated with differential expression of intrahepatic interferon-stimulated genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2010;52:1888–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dill MT, Duong FH, Vogt JE, et al. Interferon-induced gene expression is a stronger predictor of treatment response than IL28B genotype in patients with hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1021–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiraga N, Abe H, Imamura M, et al. Impact of viral amino acid substitutions and host interleukin-28b polymorphism on replication and susceptibility to interferon of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011;54:764–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.