Abstract

Flagellin is a potent activator of a broad range of cell types involved in innate and adaptive immunity. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of flagellin as an adjuvant, as well as its ability to promote cytokine production by a range of innate cell types, trigger a generalized recruitment of T and B lymphocytes to secondary lymphoid sites, and activate TLR5+CD11c+ cells and T lymphocytes in a manner that is distinct from cognate Ag recognition. The plasticity of flagellin has allowed for the generation of a range of flagellin–Ag fusion proteins that have proven to be effective vaccines in animal models. This review summarizes the state of our current understanding of the adjuvant effect of flagellin and addresses important areas of current and future research interest.

In 1998,Ciacci-Woolwine et al.(1)reported that the major structural protein of Gram-negative flagella, FliC (also termed flagellin), is a potent inducer of cytokine production in a human promonocytic cell line, with maximal activity in the subnanomolar range. A later study (2) established that flagellin rapidly induces activation of IL-1R–associated kinase 1, a finding that raised the possibility that the receptor for flagellin was a member of the TLR family. Several subsequent studies established that TLR5 is the receptor for extracellular flagellin (3-5). When flagellin is present intracellularly, for example, during infection by a flagel-lated intracellular bacterium, it signals via IPAF (also termed NLRC4) (6, 7) and Naip5 (8). The conserved C- and N-terminal domains of flagellin are required for binding to TLR5 (9-11), whereas the interaction of flagellin with Naip5 seems to involve the 35 C-terminal amino acids of flagellin (8). The cell-type expression of TLR5 and its signaling pathway were reviewed previously (12) and, therefore, will not be discussed. Instead, this review focuses on our knowledge of the cellular mechanisms that are responsible for the potent adjuvant effect of flagellin.

The first studies describing the adjuvant activity of flagellin were conducted by Ruth Arnon and colleagues (13-19). These studies clearly demonstrated that heterologous peptide sequences could be inserted into flagellin to create vaccines that were effective at eliciting humoral immunity in the absence of an adjuvant. A striking feature of these vaccines was that prior immunity to flagellin did not impair their ability to elicit robust responses (13). This finding was confirmed by Honko et al. (20). It is quite likely that this property of flagellin is due to its high affinity for TLR5 (21, 22) and the limited receptor occupancy required to elicit maximal cellular activation (22). During the past decade, an ever-increasing number of studies have described the adjuvant property of flagellin in the context of a broad range of recombinant vaccines (13-20, 23-43) (Table I). In some cases, flagellin and Ag are used separately, whereas, in others, they are used as fusion proteins. Flagellin can obviously serve as its own adjuvant in the context of a response directed against one or more epitopes in flagellin (29).

Table I. Recombinant flagellin-based vaccines.

| Recombinant Vaccine | Species | Route of Administration |

Response | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flagellin-influenza virus hemagglutinin epitopes | Mice | s.c. | Ab production |

13, 15-19, 23 |

| i.n. | In vitro virus neutralization Protection against in vivo challenge |

23 | ||

| Flagellin-influenza virus hemagglutinin globular head domain | Mice | s.c. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

35 |

| Flagellin-influenza virus M2e ectodomain | Mice | s.c. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

39 |

| Flagellin-Schistosoma mansoni epitope | Mice | i.n. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

14 |

| Flagellin-Campylobacter coli maltose-binding protein | Mice | i.n. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

24 |

| Flagellin-Escherichia coli colonization factor I epitope | Mice | i.p. | Ab production | 25 |

| Flagellin | Mice | s.c | Protection against in vivo challenge | 29 |

| Oral | Ab production Reduced bacterial load |

28 | ||

| Flagellin-Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin | Mice | Oral | Ab production | 26 |

| Flagellin-enhanced GFP | Mice | s.c. | In vitro CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity | 27 |

| In vitro | In vitro CD4+ T cell proliferation | |||

| Flagellin + Streptococcus mutans saliva-binding region of adhesion AgI/II |

Mice | i.n. | Ab production | 30 |

| In vitro CD4+ T cell proliferation | ||||

| Flagellin + Yersinia pestis F1 Ag or F1/V fusion | Mice | i.n. | Ab production | 20 |

| Nonhuman primates |

i.n. | Protection against in vivo challenge | ||

| Ab production | ||||

| Flagellin-F1-V fusion | Mice | i.m. | Ab production | 40 |

| Nonhuman primates |

Protection against in vivo challenge | |||

| i.m. | Ab production | |||

| Flagellin + tetanus toxoid | Mice | i.n. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

31 |

| Flagellin-OVA | Mice | s.c. | Ab production | 32 |

| i.m. | CD8+ T cell activation | |||

| CD4+ proliferation and cytokine production |

44 | |||

| Flagellin-West Nile virus envelope protein | Mice | s.c. | Ab production | 33 |

| i.p. | Protection against in vivo challenge | |||

| Flagellin + OVA | Mice | i.n. | Airway hyperresponsiveness Eosinophilic inflammation Th2 cytokine production |

34 |

| Flagellin-Plasmodium surface protein-1 | Mice | s.c. | Ab production | 36, 37 |

| Flagellin-Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein epitope | Mice | i.n. s.c. |

In vivo CD8+ T cell activation | 38 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprF epitope 8-OprI-flagellin type A and B |

Mice | i.m. | Ab production | 41 |

| Nonhuman primates |

Protection against in vivo challenge | |||

| i.m. | Ab production | 42 | ||

| Vaccinia virus L1R-flagellin and flagellin-B5R | Mice | i.m. | Ab production Protection against in vivo challenge |

43 |

Mechanisms underlying the adjuvant effect of flagellin

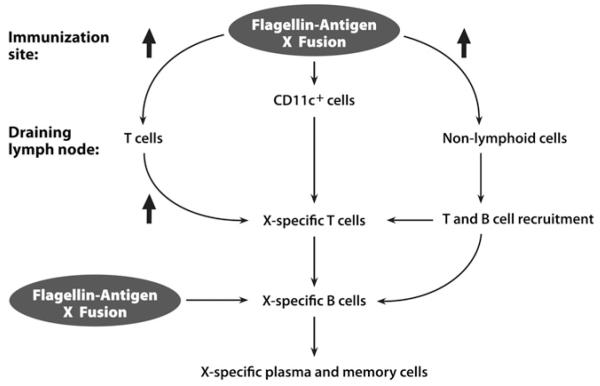

In view of the substantial potency of flagellin as an adjuvant, especially in the context of fusion proteins, considerable effort has focused on the mechanisms that are responsible for its adjuvant effect. Studies in mice (20, 45) revealed that the dose of flagellin required to promote a maximal Ag-specific humoral immune response was as much as 10-fold lower than the dose required to elicit a maximal innate response. Thus, the strength of a humoral response is not linearly related to the strength of an innate response but rather requires only a threshold level of innate immunity to drive the humoral response. The lack of a simple linear relationship between the magnitude of the flagellin-induced innate and adaptive responses is most likely due to the ability of flagellin to promote a number of related innate-immune processes that are critical for the development of a humoral response (Fig. 1). These processes include the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by lymphoid and nonlymphoid cells, the generalized recruitment of T and B lymphocytes to secondary lymphoid sites, dendritic cell (DC) activation, and direct activation of T lymphocytes. Following intramuscular (i.m.), fluorescently labeled flagellin or flagellin fusion proteins are rapidly transported to the lymphatic sinuses of the draining node and are retained for several hours (J.T. Bates and S.B. Mizel, unpublished observations). The rapid and efficient accumulation of flagellin and flagellin fusion proteins results in a high concentration in the draining lymph nodes and, thus, contributes to the overall potency of flagellin-based vaccines. Sixt and colleagues (46) found that soluble Ag injected s.c. is rapidly delivered via an LYVE-1+ conduit system to high endothelial venules (HEV) in the T cell zone of the draining lymph node and that low levels of Ag are detectable in the lumen of the HEV. Importantly, they also found that conduit-associated DCs were able to capture Ag moving through the conduit system for processing and presentation. This mechanism of Ag delivery provides a route by which parenterally administered flagellin can directly activate DC and HEV in the draining lymph nodes. The induction of cytokines and chemokines is a key first step in the adjuvant effect of flagellin (4, 45) and probably involves a number of flagellin-responsive cell types (e.g., DCs, epithelial cells, and lymph node stromal cells) (47). Although Pegu et al. (48) did not detect a direct effect of flagellin on lymphatic endothelial cells, other investigators reported that microvascular endothelial cells express TLR5 and respond to flagellin (49). Independent of the source of cytokine-and chemokine-producing cells, it is clear that flagellin can also promote a marked increase in T and B lymphocyte recruitment to draining lymph nodes (50), which increases the likelihood of Ag-specific lymphocytes encountering their cognate Ag.

FIGURE 1.

Cellular mechanisms for the adjuvant effect of flagellin. The major cellular targets of flagellin are CD11c+ cells, cytokine- and chemokine-producing nonlymphoid cells, and T cells. The cumulative effect of the activation of these cell types results in enhanced activation of B cells and the generation of plasma and memory cells. The short thick arrows represent activation events. The binding of the flagellin-Ag X fusion to B cells does not result in a flagellin-mediated activation event but is linked to the normal response of the B cell upon binding its cognate Ag.

Although it is a well-accepted notion that most adjuvants, especially TLR agonists, work, in part, by inducing DC maturation/activation and migration to secondary lymphoid sites (reviewed in Ref. 51), there is considerable disagreement in the literature regarding the effect of flagellin on DCs and their precursors. Some studies found that stimulation with flagellin results in substantial activation of murine bone marrow-derived DCs (52-55), whereas other investigators reported an effect on human, but not murine, DCs (56). We found that flagellin had a very small, but significant, effect on CD80 expression and IL-6 production (56). The stimulatory effect of recombinant flagellin on human myeloid-derived DCs was confirmed in several additional studies (57, 58). A stimulatory effect of flagellin on human DC activation was also observed using flagellin-expressing SV5 (58). In the case of the SV5 virus expressing flagellin, the flagellin signaling may be the result of a combination of extracellular and intracellular signaling. Salazar-Gonzalez et al. (59) reported that the stimulatory effect of flagellin on splenic DCs was indirect.

The diversity of findings with DCs most likely results from a combination of biochemical and methodological factors. The quality of the flagellin is a major variable that can dramatically influence experimental outcomes. Several studies used commercial flagellin preparations that require concentrations >100-fold greater than needed to generate maximal signaling via TLR5 (i.e., 10−10–10−9 M). Using such high concentrations unavoidably increases the level of contaminating nucleic acids and endotoxin and may result in TLR5-independent DC activation. Passage of flagellin through a polymyxin B column effectively reduces the level of endotoxin contamination, but it does not remove nucleic acids that possess the ability to signal via other TLRs. We found that removal of contaminating nucleic acids can be achieved using Acrodisc syringe filters (Pall, Port Washington, NY). Consequently, it is crucial to use a means of quality control to determine the relative contribution of TLR5-independent and TLR5-dependent mechanisms with a given flagellin preparation. The use of TLR5− and flagellin-nonresponsive RAW264.7 cells (60) and RAW264.7 cells stably transfected with TLR5 (39, 40) to verify the purity of flagellin, Ag, and flagellin-fusion protein preparations is highly recommended. A positive result with the TLR5-deficient RAW264.7 cells is a clear indication of contaminating bioactive substances. We also found that long-term storage of some flagellin fusion proteins may result in the formation of large aggregates that function in a TLR5-independent manner. A method such as dynamic light scattering is a valuable means by which to ensure that flagellin and flagellin fusion proteins are monomeric and not aggregated (40).

The ability of cells to respond to flagellin may also be significantly affected by their state of differentiation. For example, Ciacci-Woolwine et al. (61) found that flagellin responsiveness in a human promonocytic cell line could be markedly enhanced if the cells were first induced to differentiate into a more macrophage-like phenotype. Similarly, human myeloid-derived DCs that have been cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in medium containing human serum are fully responsive to flagellin, whereas the same cells cultured in FBS-containing medium are only marginally responsive (C. Hickman, J.T. Bates, and S.B. Mizel, unpublished observations). We favor the view that in vitro maturation of bone marrow cells yields a population of cells that has limited sensitivity to flagellin (44) and that a significant portion of the activation seen in several studies (51-54) may be affected by uncharacterized variables in the culture conditions for bone marrow-derived DC maturation or the action of nonflagellin components in the flagellin preparations used in these studies.

In mice, the adjuvant effect of flagellin on the Ag-specific CD4+ T cell response requires direct stimulation of tlr5+/+ CD11c+ cells (56). TLR5 expression by non-DCs is not sufficient to stimulate a response in the absence of tlr5+/+CD11c+ cells. The markedly enhanced response to flagellin fusion proteins compared with flagellin + Ag (~10-fold) is most likely due to the more efficient delivery of adjuvant and Ag to the same TLR5+ APC. However, as noted earlier (59), some investigators have argued that flagellin-induced DC activation occurs via an indirect mechanism. It is possible that the mechanism of activation, direct or indirect, is specific to a given immunologic site. For example, in contrast to splenic DCs (59), lamina propria DCs seem to be directly activated by flagellin (62).

Although the majority of studies on the in vivo adjuvant effect of flagellin have been carried out in murine systems, there are, to our knowledge, no murine studies demonstrating a direct effect of flagellin on T cells. However, a growing body of evidence generated from in vitro studies on human T cells provides strong support for the conclusion that flagellin can directly stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Caron et al. (63) found that flagellin, in combination with the TLR7/8 ligand R-848, can stimulate enriched human memory CD4+ T cells to proliferate and produce cytokine when combined with other stimuli, such as suboptimal anti-CD3 Abs or exogenous IL-2. Similarly, Crellin et al. (64) found that flagellin is equivalent to anti-CD28 in stimulating CD4+ T cell proliferation in combination with anti-CD3. Upregulation of T cell activation markers by enriched CD4+ T cells following stimulation with flagellin has also been reported (65). With regard to CD8+ T cells, McCarron and Reen (66) reported that flagellin can directly stimulate human neonatal CD8+ T cells to proliferate and produce cytokines and granzyme B. Thus, in addition to inducing cytokine production, activating DC, and promoting lymphocyte migration to secondary lymphoid sites, flagellin may facilitate the activation of T cells by a direct mechanism that is independent of T cell recognition of cognate Ag. However, the degree to which direct Ag-independent T cell activation contributes to the overall adjuvant effect of flagellin remains to be determined. As an Ag by itself, flagellin is highly immunogenic [e.g., (29)]; thus, the immune response directed against an Ag linked to flagellin might be positively influenced by the activation of flagellin-specific CD4+ T cells. This interesting possibility has yet to be directly evaluated, but it clearly merits attention. Thus, there may be at least two ways in which T cells can be activated during the course of the response to a flagellin-based vaccine.

Although most data are consistent with an immunostimulatory effect of flagellin on T cells, flagellin may also activate regulatory components of the immune response. Notably, Crellin et al. (64) found that regulatory T cells (Tregs) express higher levels of TLR5 mRNA than do CD252 T cells and that treatment of Tregs with flagellin enhances the regulatory activity of these cells. Thus, it seems that flagellin promotes the activation of Tregs and effector cells. However, flagellin may also simultaneously inhibit TCR-mediated activation through a suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS-1)–dependent mechanism (67). Because Treg recognition of cognate Ag occurs via the TCR, the SOCS-1–mediated mechanism of inhibition following stimulation with flagellin may also inhibit Treg activation. The potential roles of flagellin-induced Treg activation and SOCS-1-dependent regulation in the overall adjuvant effect of flagellin remain to be determined.

With regard to the possible action of flagellin on B cells, Pasare and Medzhitov (68) reported that a direct effect of flagellin on B cells was a requirement for the activation of these cells. However, we have not detected TLR5 expression on the surface of murine B cells, nor have we observed flagellin-induced IL-1R–associated kinase 1 activation in B cells (C. Hickman, J.T. Bates, and S.B. Mizel, unpublished observations). In view of the discrepancy in results, additional studies on B cells are clearly warranted.

Although flagellin does not seem to signal directly via B cells, its stimulatory effect on DC and perhaps T cells promotes a dramatic increase in T cell-dependent (20, 69) Ab production (20, 23-28, 30-33, 35, 36, 41, 42, 70). The humoral response is generally characterized by high titers of IgG1 and IgG2a that provide complete protection against a targeted pathogen. In no instance is there any significant increase in Ag-specific IgE (20). However, when CD4+ T cell cytokine profiles were evaluated (53, 71), it seemed that flagellin induced a Th2-type response. These results demonstrate that Ab and cytokine profiles do not always match and indicate that some caution is warranted when assigning a particular phenotype to the observed response.

Although there is consensus regarding the ability of flagellin to promote robust CD4+ T cell-dependent responses, the situation with CD8+ T cells is not quite settled. Two studies (54, 72) did not observe any significant effect of flagellin on CD8+ T cell activation, whereas three reports (27, 32, 38) documented a significant effect of flagellin on the activation of these cells. The major distinction between the two sets of studies is the use of flagellin fusion proteins in the studies demonstrating a positive effect of flagellin. The need for a physical link between flagellin and Ag is not a requirement for the adjuvant activity of flagellin in CD4+ T cell-dependent humoral responses (20, 31). The simplest explanation for the fusion protein requirement is that DC uptake via TLR5 provides a means for efficient internalization and access to the Ag-processing pathway. However, we found that the activation of CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo using a flagellin-OVA fusion protein is TLR5 and MyD88 independent (J.T. Bates, A.H. Graff, and S.B. Mizel, submitted for publication). Furthermore, the enhancing effect of a flagellin-OVA fusion protein (relative to OVA alone) is not dependent on the conserved regions of the protein. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that in the context of a fusion protein, flagellin delivers the Ag in a form that facilitates Ag processing but does not contribute to the response via TLR5 signaling.

Advantages of flagellin-based vaccines

Flagellin has a number of other advantages that make it an attractive candidate for use in human vaccines. It is effective at very low doses [e.g., 1–10 μg in nonhuman primates (42)], does not promote IgE responses (20), prior immunity to flagellin does not impair its adjuvant activity (13, 20), Ag sequences can be inserted at the amino or C terminus or within the hypervariable region of the protein without any loss of flagellin signaling via TLR5 (14, 15, 18, 19, 23-26, 33, 35, 36, 40, 70), has no detectable toxicity in rabbits when given intranasally (i.n.) or i.m. using a two-dose protocol (100–500 μg) over 28 d (S.B. Mizel, unpublished observations), and it can easily be made in large amounts under GMP conditions (40). However, we must await the publication of phase I clinical trial results in humans to determine whether recombinant flagellin-based vaccines trigger adverse events, such as a systemic cytokine storm or intense local inflammation at the site of immunization, which would limit their use. In view of the extraordinary potency of flagellin, it is quite likely that the occurrence of such side effects can be avoided by using very low doses of flagellin-fusion proteins (e.g., 1–10 μg) (42).

Although flagellin exhibits tremendous plasticity in creating Ag-fusion proteins, there are limitations that are specific for individual Ag sequences. In some instances (35, 40), insertion in the hypervariable region is preferable. For example, Song et al. (35) found that insertion of the avian influenza virus hemagglutinin globular head sequence in the hypervariable region of flagellin was optimal for the generation of protective Abs. Similarly, the insertion of the F1 and V Ags of Yersinia pestis in the hypervariable region of flagellin produced a highly effective vaccine against respiratory challenge with Y. pestis in mice (40). However, replacement of the hypervariable region of flagellin with some Ag sequences results in proteins that aggregate immediately upon removal from urea or guanidine or, alternatively, aggregate after long-term storage at 4°C or colder. In the case of flagellin fusions designed to generate protective Abs, the position of Ag sequences can dramatically affect the folding of the Ag within the fusion protein, such that the induced Abs do not recognize the native Ag. For example, we found that replacement of the hypervariable region of flagellin with the vaccinia virus protein L1R results in a vaccine that does not generate Abs against native L1R (K.N. Delaney, J.P. Phipps, and S.B. Mizel, unpublished observations). However, if L1R sequences are placed at the N terminus of flagellin, Abs are generated that interact with native L1R (43). Although it is not possible to predict whether a specific insertion site will be appropriate for a given Ag, we have found that placement at the N terminus of flagellin is an excellent starting point for creating a fusion protein.

Concluding remarks

There are a number of key questions related to the adjuvant effect of flagellin that remain to be answered. For example, is TLR5 expression and responsiveness in DCs developmentally regulated? Are there distinct subpopulations of flagellin-responsive DCs? To what extent do direct effects of flagellin on T cells contribute to the overall adaptive response?

With regard to the potential use of flagellin in human vaccines, there are a number of areas that are worthy of continued investigation. Many vaccines that provide protection to the young and middle-aged populations are far less effective in older populations (e.g., Ref. 73). Adjuvants that enhance immunogenicity in the aged immune system are clearly needed. Flagellin is effective as an adjuvant in the aged mouse immune system but not to the degree as in young mice (16, 50). The effect of additional immunizations on Ab titers and affinity remains to be determined. Although flagellin is by itself a very effective adjuvant, it can also enhance other adjuvant systems. Incorporation of flagellin into influenza virus-like particles results in increased virus-specific IgG production and cellular responses to MHC classes I and II-restricted Ags (74). Similar enhancement in the Ab response was seen following oral immunization with nanoparticles coated with flagellin (75) or orally administered bacteriophage displaying flagellin (76). Although a number of flagellin-based vaccines for infectious diseases have already entered clinical trials, many basic science questions and potential uses of flagellin as an adjuvant remain to be explored [e.g., in vaccines to diminish symptoms of allergy (34) or to target tumor cells]. The potential of this fascinating protein seems to be almost unlimited.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants P01 AI 60642 and U01AI070440 (to S.B.M.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- DC

dendritic cell

- HEV

high endothelial venule

- i.m.

intramuscular

- i.n.

intranasally

- SOCS-1

suppressor of cytokine signaling 1

- Treg

regulatory T cell

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ciacci-Woolwine F, Blomfield IC, Richardson SH, Mizel SB. Salmonella flagellin induces tumor necrosis factor alpha in a human promonocytic cell line. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1127–1134. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1127-1134.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moors MA, Li L, Mizel SB. Activation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase by gram-negative flagellin. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4424–4429. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4424-4429.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizel SB, Snipes JA. Gram-negative flagellin-induced self-tolerance is associated with a block in interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase release from toll-like receptor 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:22414–22420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franchi L, Amer A, Body-Malapel M, Kanneganti TD, Ozören N, Jagirdar R, Inohara N, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, et al. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1β in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miao EA, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Dors M, Clark AE, Bader MW, Miller SI, Aderem A. Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1β via Ipaf. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:569–575. doi: 10.1038/ni1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lightfield KL, Persson J, Brubaker SW, Witte CE, von Moltke J, Dunipace EA, Henry T, Sun YH, Cado D, Dietrich WF, et al. Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/ni.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly MA, Steiner TS. Two nonadjacent regions in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli flagellin are required for activation of toll-like receptor 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40456–40461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eaves-Pyles TD, Wong HR, Odoms K, Pyles RB. Salmonella flagellin-dependent proinflammatory responses are localized to the conserved amino and carboxyl regions of the protein. J. Immunol. 2001;167:7009–7016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy KGK, Deb A, Goonesekera S, Szabó C, Salzman AL. Identification of conserved domains in Salmonella muenchen flagellin that are essential for its ability to activate TLR5 and to induce an inflammatory response in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5667–5675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honko AN, Mizel SB. Effects of flagellin on innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Res. 2005;33:83–101. doi: 10.1385/IR:33:1:083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Yedidia T, Arnon R. Effect of pre-existing carrier immunity on the efficacy of synthetic influenza vaccine. Immunol. Lett. 1998;64:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Yedidia T, Tarrab-Hazdai R, Schechtman D, Arnon R. Intranasal administration of synthetic recombinant peptide-based vaccine protects mice from infection by Schistosoma mansoni. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4360-4366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Yedidia T, Marcus H, Reisner Y, Arnon R. Intranasal administration of peptide vaccine protects human/mouse radiation chimera from influenza infection. Int. Immunol. 1999;11:1043–1051. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben-Yedidia T, Abel L, Arnon R, Globerson A. Efficacy of anti-influenza peptide vaccine in aged mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1998;104:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon SH, Ben-Yedidia T, Arnon R. Intranasal immunization with synthetic recombinant vaccine containing multiple epitopes of influenza virus. Vaccine. 2002;20:2772–2780. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi R, Arnon R. Synthetic recombinant influenza vaccine induces efficient long-term immunity and cross-strain protection. Vaccine. 1996;14:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00088-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McEwen J, Levi R, Horwitz RJ, Arnon R. Synthetic recombinant vaccine expressing influenza haemagglutinin epitope in Salmonella flagellin leads to partial protection in mice. Vaccine. 1992;10:405–411. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90071-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honko AN, Sriranganathan N, Lees CJ, Mizel SB. Flagellin is an effective adjuvant for immunization against lethal respiratory challenge with Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1113–1120. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1113-1120.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDermott PF, Ciacci-Woolwine F, Snipes JA, Mizel SB. High-affinity interaction between gram-negative flagellin and a cell surface polypeptide results in human monocyte activation. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:5525–5529. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5525-5529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizel SB, West AP, Hantgan RR. Identification of a sequence in human toll-like receptor 5 required for the binding of Gram-negative flagellin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23624–23629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adar Y, Singer Y, Levi R, Tzehoval E, Perk S, Banet-Noach C, Nagar S, Arnon R, Ben-Yedidia T. A universal epitope-based influenza vaccine and its efficacy against H5N1. Vaccine. 2009;27:2099–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee LH, Burg E, III, Baqar S, Bourgeois AL, Burr DH, Ewing CP, Trust TJ, Guerry P. Evaluation of a truncated recombinant flagellin subunit vaccine against Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5799–5805. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5799-5805.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.das Graças Luna M, Sardella FF, Ferreira LC. Salmonella flagellin fused with a linear epitope of colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) can prime antibody responses against homologous and heterologous fimbriae of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 2000;151:575–582. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira CM, Guth BE, Sbrogio-Almeida ME, Castilho BA. Antibody response against Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin expressed as fusions to flagellin. Microbiology. 2001;147:861–867. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuadros C, Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Dominguez AL, McClelland M, Lustgarten J. Flagellin fusion proteins as adjuvants or vaccines induce specific immune responses. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2810-2816.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strindelius L, Filler M, Sjöholm I. Mucosal immunization with purified flagellin from Salmonella induces systemic and mucosal immune responses in C3H/HeJ mice. Vaccine. 2004;22:3797–3808. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McSorley SJ, Cookson BT, Jenkins MK. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J. Immunol. 2000;164:986–993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pino O, Martin M, Michalek SM. Cellular mechanisms of the adjuvant activity of the flagellin component FljB of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium to potentiate mucosal and systemic responses. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:6763–6770. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6763-6770.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SE, Kim SY, Jeong BC, Kim YR, Bae SJ, Ahn OS, Lee JJ, Song HC, Kim JM, Choy HE, et al. A bacterial flagellin, Vibrio vulnificus FlaB, has a strong mucosal adjuvant activity to induce protective immunity. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:694–702. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.694-702.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huleatt JW, Jacobs AR, Tang J, Desai P, Kopp EB, Huang Y, Song L, Nakaar V, Powell TJ. Vaccination with recombinant fusion proteins incorporating Toll-like receptor ligands induces rapid cellular and humoral immunity. Vaccine. 2007;25:763–775. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald WF, Huleatt JW, Foellmer HG, Hewitt D, Tang J, Desai P, Price A, Jacobs A, Takahashi VN, Huang Y, et al. A West Nile virus recombinant protein vaccine that coactivates innate and adaptive immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195:1607–1617. doi: 10.1086/517613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SE, Koh YI, Kim MK, Kim YR, Kim SY, Nam JH, Choi YD, Bae SJ, Ko YJ, Ryu HJ, et al. Inhibition of airway allergic disease by co-administration of flagellin with allergen. J. Clin. Immunol. 2008;28:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song L, Zhang Y, Yun NE, Poussard AL, Smith JN, Smith JK, Borisevich V, Linde JJ, Zacks MA, Li H, et al. Superior efficacy of a recombinant flagellin:H5N1 HA globular head vaccine is determined by the placement of the globular head within flagellin. Vaccine. 2009;27:5875–5884. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bargieri DY, Leite JA, Lopes SC, Sbrogio-Almeida ME, Braga CJM, Ferreira LC, Soares IS, Costa FT, Rodrigues MM. Immunogenic properties of a recombinant fusion protein containing the C-terminal 19 kDa of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 and the innate immunity agonist FliC flagellin of Salmonella typhimurium. Vaccine. 2010;28:2818–2826. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bargieri DY, Rosa DS, Braga CJM, Carvalho BO, Costa FTM, Espíndola NM, Vaz AJ, Soares IS, Ferreira LC, Rodrigues MM. New malaria vaccine candidates based on the Plasmodium vivax Merozoite Surface Protein-1 and the TLR-5 agonist Salmonella Typhimurium FliC flagellin. Vaccine. 2008;26:6132–6142. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braga CJM, Massis LM, Sbrogio-Almeida ME, Alencar BCG, Bargieri DY, Boscardin SB, Rodrigues MM, Ferreira LCS. CD8+ T cell adjuvant effects of Salmonella FliCd flagellin in live vaccine vectors or as purified protein. Vaccine. 2010;28:1373–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huleatt JW, Nakaar V, Desai P, Huang Y, Hewitt D, Jacobs A, Tang J, McDonald W, Song L, Evans RK, et al. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine. 2008;26:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizel SB, Graff A, Sriranganathan N, Ervin S, Lees CJ, Lively MO, Hantgan RR, Thomas MJ, Wood J, Bell B. Flagellin-F1-V fusion protein is an effective plague vaccine in mice and two species of nonhuman primates. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:21–28. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00333-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weimer ET, Lu H, Kock ND, Wozniak DJ, Mizel SB. A fusion protein vaccine containing OprF epitope 8, OprI, and type A and B flagellins promotes enhanced clearance of nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:2356–2366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00054-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weimer ET, Ervin SE, Wozniak DJ, Mizel SB. Immunization of young African green monkeys with OprF epitope 8-OprI-type A- and B-flagellin fusion proteins promotes the production of protective antibodies against nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Vaccine. 2009;27:6762–6769. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delaney KN, Phipps JP, Johnson JB, Mizel SB. A recombinant flagellin-poxvirus fusion protein vaccine elicits complement-dependent protection against respiratory challenge with vaccinia virus in mice. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:201–210. doi: 10.1089/vim.2009.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates JT, Uematsu S, Akira S, Mizel SB. Direct stimulation of tlr5+/+ CD11c+ cells is necessary for the adjuvant activity of flagellin. J. Immunol. 2009;182:7539–7547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honko AN, Mizel SB. Mucosal administration of flagellin induces innate immunity in the mouse lung. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:6676–6679. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6676-6679.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sixt M, Kanazawa N, Selg M, Samson T, Roos G, Reinhardt DP, Pabst R, Lutz MB, Sorokin L. The conduit system transports soluble antigens from the afferent lymph to resident dendritic cells in the T cell area of the lymph node. Immunity. 2005;22:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders CJ, Moore DA, III, Williams IR, Gewirtz AT. Both radioresistant and hemopoietic cells promote innate and adaptive immune responses to flagellin. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7184–7192. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pegu A, Qin S, Fallert Junecko BA, Nisato RE, Pepper MS, Reinhart TA. Human lymphatic endothelial cells express multiple functional TLRs. J. Immunol. 2008;180:3399–3405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maaser C, Heidemann J, von Eiff C, Lugering A, Spahn TW, Binion DG, Domschke W, Lugering N, Kucharzik T. Human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells express Toll-like receptor 5: a binding partner for bacterial flagellin. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5056–5062. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bates JT, Honko AN, Graff AH, Kock ND, Mizel SB. Mucosal adjuvant activity of flagellin in aged mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008;129:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benko S, Magyarics Z, Szabó A, Rajnavölgyi E. Dendritic cell sub-types as primary targets of vaccines: the emerging role and cross-talk of pattern recognition receptors. Biol. Chem. 2008;389:469–485. doi: 10.1515/bc.2008.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsujimoto H, Uchida T, Efron PA, Scumpia PO, Verma A, Matsumoto T, Tschoeke SK, Ungaro RF, Ono S, Seki S, et al. Flagellin enhances NK cell proliferation and activation directly and through dendritic cell-NK cell interactions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:888–897. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0105051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vicente-Suarez I, Brayer J, Villagra A, Cheng F, Sotomayor EM. TLR5 ligation by flagellin converts tolerogenic dendritic cells into activating antigen-presenting cells that preferentially induce T-helper 1 responses. Immunol. Lett. 2009;125:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Didierlaurent A, Ferrero I, Otten LA, Dubois B, Reinhardt M, Carlsen H, Blomhoff R, Akira S, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Sirard J-C. Flagellin promotes myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent development of Th2-type response. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6922–6930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Datta SK, Redecke V, Prilliman KR, Takabayashi K, Corr M, Tallant T, DiDonato J, Dziarski R, Akira S, Schoenberger SP, Raz E. A subset of Toll-like receptor ligands induces cross-presentation by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4102–4110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Means TK, Hayashi F, Smith KD, Aderem A, Luster AD. The Toll-like receptor 5 stimulus bacterial flagellin induces maturation and chemokine production in human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5165–5175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agrawal S, Agrawal A, Doughty B, Gerwitz A, Blenis J, Van Dyke T, Pulendran B. Cutting edge: different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos. J. Immunol. 2003;171:4984–4989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arimilli S, Johnson JB, Clark KM, Graff AH, Alexander-Miller MA, Mizel SB, Parks GD. Engineered expression of the TLR5 ligand flagellin enhances paramyxovirus activation of human dendritic cell function. J. Virol. 2008;82:10975–10985. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salazar-Gonzalez R-M, Srinivasan A, Griffin A, Muralimohan G, Ertelt JM, Ravindran R, Vella AT, McSorley SJ. Salmonella flagellin induces bystander activation of splenic dendritic cells and hinders bacterial replication in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007;179:6169–6175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.West AP, Dancho BA, Mizel SB. Gangliosides inhibit flagellin signaling in the absence of an effect on flagellin binding to toll-like receptor 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9482–9488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ciacci-Woolwine F, McDermott PF, Mizel SB. Induction of cytokine synthesis by flagella from gram-negative bacteria may be dependent on the activation or differentiation state of human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5176–5185. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5176-5185.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K, Jang MH, Yang B-G, Jung Y-J, Nishiyama M, Sato S, Tsujimura T, Yamamoto M, Yokota Y, et al. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caron G, Duluc D, Frémaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, Delneste Y. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-γ production by memory CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2005;175:1551–1557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crellin NK, Garcia RV, Hadisfar O, Allan SE, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Human CD4+ T cells express TLR5 and its ligand flagellin enhances the suppressive capacity and expression of FOXP3 in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2005;175:8051–8059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simone R, Floriani A, Saverino D. Stimulation of human CD4 T lymphocytes via TLR3, TLR5 and TLR7/8 up-regulates expression of costimulatory and modulates proliferation. Open Microbiol. J. 2009;3:1–8. doi: 10.2174/1874285800903010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCarron M, Reen DJ. Activated human neonatal CD8+ T cells are subject to immunomodulation by direct TLR2 or TLR5 stimulation. J. Immunol. 2009;182:55–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Okugawa S, Yanagimoto S, Tsukada K, Kitazawa T, Koike K, Kimura S, Nagase H, Hirai K, Ota Y. Bacterial flagellin inhibits T cell receptor-mediated activation of T cells by inducing suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 (SOCS-1) Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1571–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders CJ, Yu Y, Moore DA, III, Williams IR, Gewirtz AT. Humoral immune response to flagellin requires T cells and activation of innate immunity. J. Immunol. 2006;177:2810–2818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chauhan N, Kumar R, Badhai J, Preet A, Yadava PK. Immunogenicity of cholera toxin B epitope inserted in Salmonella flagellin expressed on bacteria and administered as DNA vaccine. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2005;276:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-2240-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cunningham AF, Khan M, Ball J, Toellner K-M, Serre K, Mohr E, MacLennan CM. Responses to the soluble fagellar protein FliC are Th2, while those to FliC on Salmonella are Th1. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:2986–2995. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwarz K, Storni T, Manolova V, Didierlaurent A, Sirard J-C, Röthlisberger P, Bachmann MF. Role of Toll-like receptors in costimulating cytotoxic T cell responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:1465–1470. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sambhara S, McElhaney JE. Immunosenescence and influenza vaccine efficacy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;333:413–429. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang BZ, Quan FS, Kang SM, Bozja J, Skountzou I, Compans RW. Incorporation of membrane-anchored flagellin into influenza virus-like particles enhances the breadth of immune responses. J. Virol. 2008;82:11813–11823. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01076-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salman HH, Irache JM, Gamazo C. Immunoadjuvant capacity of flagellin and mannosamine-coated poly(anhydride) nanoparticles in oral vaccination. Vaccine. 2009;27:4784–4790. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Synnott A, Ohshima K, Nakai Y, Tanji Y. IgA response of BALB/c mice to orally administered Salmonella typhimurium flagellin-displaying T2 bacteriophages. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009;25:552–558. doi: 10.1002/btpr.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]