Abstract

Abnormal perceptual experiences are central to schizophrenia but the nature of these anomalies remains undetermined. We investigated contextual processing abnormalities across a comprehensive set of visual tasks. For perception of luminance, size, contrast, orientation and motion, we quantified the degree to which the surrounding visual context altered a center stimulus’ appearance. Across tasks, healthy participants showed robust contextual effects, as evidenced by pronounced misperceptions of center stimuli. Schizophrenia patients exhibited intact contextual modulations of luminance and size, but showed weakened contextual modulations of contrast, performing more accurately than controls. Strong motion and orientation context effects correlated with worse symptoms and social functioning. Importantly, the overall strength of contextual modulation across tasks did not differ between controls and schizophrenia patients. Additionally, performance measures across contextual tasks were uncorrelated, implying discrete underlying processes. These findings reveal that abnormal contextual modulation in schizophrenia is selective, arguing against the proposed unitary contextual processing dysfunction.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, center-surround, contextual effects, perception deficit, visual processing

Introduction

Impairments in visual processing are pervasive in schizophrenia, ranging from deficits in simple visual discriminations (Butler and Javitt, 2005) to abnormalities in high-level visual perception (Kim et al., 2011). These visual deficits may exacerbate and/or lead to cognitive and social problems (Uhlhaas and Mishara, 2007). Despite many reports of visual deficits in schizophrenia, their role in the symptoms and etiology of the disorder remains unclear. One obstacle to understanding the nature of visual abnormalities in schizophrenia is the concurrent presence of other performance impairments. For example, well-established attentional and working memory deficits (Lee and Park, 2005) may cause poor performance in a variety of visual tasks, making it difficult to isolate specific visual deficits.

Remarkably, abnormalities in visual processing in schizophrenia do not always show up as deficiencies in task performance. Rather visual perception in schizophrenia appears to be qualitatively different, characterized by performance deficits or performance enhancements (Barch et al., 2012, Dakin et al., 2005; Tadin et al., 2006; Uhlhaas et al., 2006, Yoon et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2010). The findings of enhanced performance in schizophrenia are difficult to attribute to non-visual factors and, thus, provide a direct behavioral measure of underlying visual abnormalities. Importantly, better-than-normal visual performance in schizophrenia seems to be restricted to tasks of spatial context effects in visual perception, wherein the perceptual appearance of a visual feature depends on its surrounding spatial context. For example, in the well-known Ebbinghaus illusion (Figure 1E), a circle surrounded by larger circles appears smaller than the same circle presented alone. Similarly, the presence of a high-contrast background decreases the apparent contrast of smaller foreground features (Figure 1B). While these illusions provide striking examples of non-veridical visual perception, they are considered functionally advantageous as they serve to enhance differences between visual features and, consequently, facilitate their segmentation from their background (Albright and Stoner, 2002). These contextual illusions, in other words, arise from vision’s adaptive propensity to emphasize relative differences among features rather than their absolute characteristics. However, a neural implementation of such contextual interactions must strike a balance between enhancement of differences between features and veridical integration of visual signals (e.g., Braddick, 1993). Consequently, both abnormally weak and abnormally strong contextual modulations constitute departures from typical vision, and are arguably maladaptive.

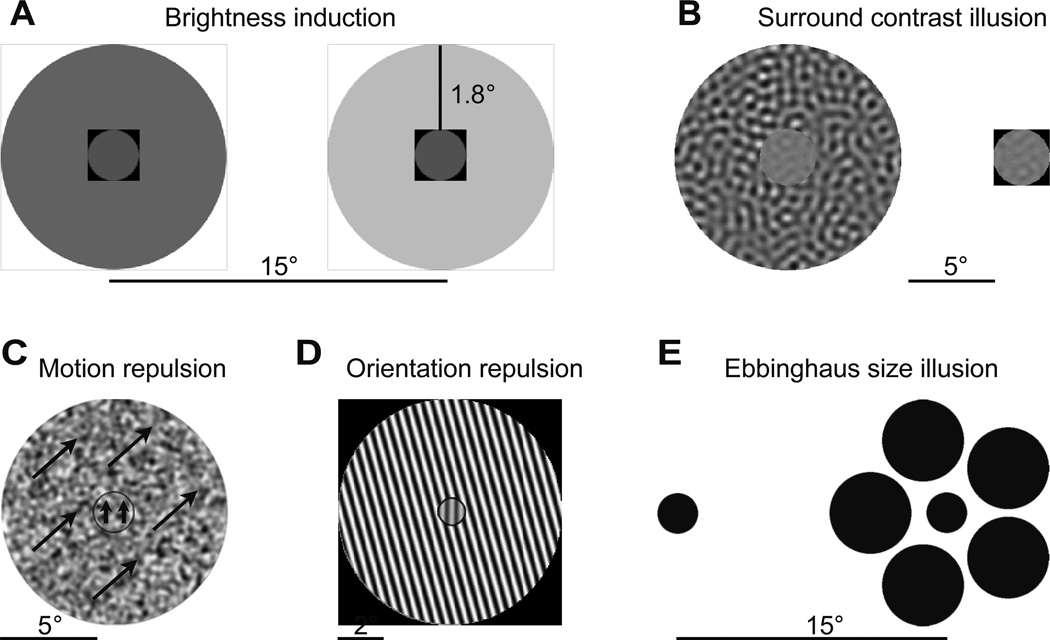

Figure 1. Illustrations of stimuli in each experiment.

Illustrations of stimuli in each experiment. (A) Brightness induction illusion: the reference stimulus (left) with darker surround is perceived as brighter than the target stimulus (right) with lighter surround. (B) Surround contrast illusion: a high contrast pattern in the surround reduces the perceived contrast of the center stimulus (left) relative to a reference stimulus of equal contrast (right). (C) Surround motion and (D) orientation repulsion illusions: the orientation or motion direction of a center stimulus appears to be repelled away from the orientation or motion direction of the surrounding pattern (arrows denote motion direction). E) Ebbinghaus size illusion: when a circle is presented with larger circles in the surround (right) the center circle is typically perceived as smaller than a stimulus of equal size (left). Scale bar denotes the stimulus display size in degrees of visual angle. Note that the spacing between stimuli in (A) is not on the same scale as the size of the stimuli.

As mentioned above, recent studies suggest that individuals with schizophrenia (SZ) may be less influenced by visual context on some tasks, thus enabling them to perceive absolute characteristics of individual features more accurately. For example, Dakin et al. (2005) reported that SZ were better at judging stimulus contrast under conditions of contextual modulation than healthy participants. This tendency toward veridical performance by SZ, however, suggests processing impairments, namely a weakening of inhibitory mechanisms that normally modulate perceived stimulus contrast (Butler et al., 2008). These results were extended by Yoon et al. (2009) who reported abnormally weak orientation-specific surround inhibition as evidenced by more accurate contrast discrimination in SZ, and, subsequently linked this deficit with abnormally low GABA levels in visual cortex, suggesting a possible causal role of impaired inhibitory mechanisms (Yoon et al., 2010). However, a recent study with a large sample size (Barch et al., 2012) failed to replicate the original results by Dakin et al. (2005) after controlling for differences in baseline performance. This result reveals a possible attentional confound and underscores that the nature of contextual contrast modulation in SZ remains an open question. In a similar vein, our group found abnormally weak surround inhibition in SZ tested on a motion perception task (Tadin et al., 2006), a deficit that involves improved detectability of large moving stimuli. In addition, SZ are less prone to the Ebbinghaus size illusion, exhibiting more accurate size perception when surrounding context is present (Uhlhaas et al., 2006). In summary, visual perception in schizophrenia is characterized by diminished contextual modulations (see Chen et al., 2008 for an exception), which paradoxically produces more accurate perception of absolute stimulus characteristics.

Considered together, results from these studies seem to suggest a generalized contextual processing deficit in schizophrenia, in line with contextual disturbances in schizophrenia reported in other sensory and cognitive domains (review by Phillips & Silverstein, 2003). These contextual processing deficits may be indicative of a unitary mechanism that is a core feature of schizophrenia (Cohen & Servan-Schreiber, 1992). The empirical evidence for this appealing hypothesis, however, is sparse, as prior studies have typically focused on single contextual tasks, several of which have yet to be replicated. Furthermore, there is considerable variability in the magnitude of observed contextual deficits within and across functional domains, and in some cases contextual abnormalities seem restricted to specific tasks (see Park et al., 2003) and subsets of patients (Tadin et al., 2006; Uhlhaas et al., 2006).

Nonetheless, the utilization of measures of contextual processing has already found its way into clinical testing (Gold et al., 2012). There has been a rapid growth in the use of context tasks in clinical trials and large-scale, NIH-supported studies of schizophrenia, including tasks focusing on visual context. Given this trajectory, it is imperative to specify and identify the conditions under which contextual processing is weakened in schizophrenia—a goal requiring comprehensive investigations. We investigated a diverse set of psychophysical tasks where spatial context is known to affect stimulus appearance, including both previously tested contextual modulations and modulations that have yet to be examined in SZ. Specifically, we investigated contextual effects in luminance, contrast, size, orientation and motion perception. In all of these tasks, weaker contextual modulation is associated with more accurate perception of visual features. Thus, if a broad contextual deficit exists, SZ should exhibit more veridical performance relative to healthy matched controls when the visual context is present. Moreover, if a common mechanism underlies contextual effects in these tasks, then the magnitude of impairment should correlate across tasks. In sum, we aimed to investigate the full range of visual context processing to elucidate the profile of impaired, intact and enhanced functions in schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Thirty individuals who met the DSM-IV (First et al, 2002) criteria for schizophrenia (SZ) and 23 healthy volunteers (CO) with no history of DSM-IV Axis-I disorders in themselves or in their families were recruited from Nashville area. Diagnosis was confirmed by trained masters- and doctoral-level psychologists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) (First et al., 2002). Exclusion criteria for the study were substance use within the last 6 months, neurological disorders or head trauma, and an IQ lower than 80. Visual acuity of all participants was 20/30 corrected or better (Optec Vision Tester 5000, Stereo Optical, Chicago, IL).

The mean illness duration of SZ was 17 years (standard deviation, SD=8). All SZ were were medicated (83% on atypical antipsychotic drugs, 60% on mood-stabilizers and 40% taking both). The mean CPZ equivalent dose was 496 mg/kg/day (SD=365). Clinical symptoms were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham, 1962), the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen, 1984), and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1983). SZ were clinically stable at the time of testing, with the mean BPRS of 13(SD=8), SAPS of 14(SD=13), and SANS of 17(SD=7).

There was no significant differences in age (p>0.05) between SZ (M=41, SD=8) and CO (M=39, SD=9), or the proportion of women (p>0.05) between SZ (37%) and CO (48%). Although SZ (M=13, SD=2) had fewer years of education than CO (M=16, SD=2) (t(51)=4.4, p<0.001), they did not differ in IQ (p>0.05), with the mean estimated IQ of 104 (SD=9) for SZ, and 106 for CO (SD=11), as assessed by the National Adult Reading Test (Nelson, 1982). Lastly, social functioning, as assessed with the Social Functioning Scale (Birchwood et al., 1990) was worse in SZ (M=111, SD=9) compared with CO (M=123, SD=5) (t(43)=5.4, p<0.001). The Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University approved this study protocol. All participants provided written, informed consent and were paid.

Apparatus

Stimuli were created using MATLAB and Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997) and were presented on a linearized CRT monitor (1280×960 resolution at 120Hz). Participants viewed the stimuli at a distance of 73 cm, with the head stabilized by a chin rest. The display background luminance was 35.2 cd/m2 except in the brightness induction task, where it was 0.11 cd/m2. The ambient illumination was 0.16 cd/m2.

Context Battery

A battery of five psychophysical tasks was administered to assess contextual effects in a broad range of stimulus dimensions: luminance, contrast, size, orientation and motion direction (Figure 1). All tasks involved a center stimulus whose perceived appearance, as judged by healthy observers, was altered by the presence of surrounding stimuli. Participants were instructed to judge the appearance of the center stimulus by comparing it to a fixed reference stimulus. For each task, the point of subjective equality (PSE) was measured to quantify the magnitude of the contextual modulation. PSEs were estimated for the brightness induction task using method of adjustment and for the remaining tasks using adaptive staircases (see below for details). With the exception of the motion task, stimuli were presented until a response was made. All tasks also included a no-context control condition, identical to the main context condition except that no surrounding context was present. These control conditions allowed us to establish that participants accurately judged stimulus dimensions tested in different tasks and to account for any baseline biases of participants.

Brightness induction task

Two circles (0.5° radius) surrounded by annuli (2.4° radius) were simultaneously presented 15° apart (Figure 1A). The luminance of the reference circle displayed on the left was fixed at 6 cd/m2 whereas its surrounding annulus was 8, 12, 16, 20, or 24 cd/m2. Measuring brightness induction with several surround luminance values allowed us to also compare the pattern in surround modulation between groups. The luminance of the annulus on the right was fixed at 24 cd/m2, while the initial luminance of its inner circle (target) was randomly chosen from a range of 2 to 14 cd/m2. Participants then adjusted the luminance of the target circle on the right to match the luminance of the reference circle on the left. Luminance was adjusted using a pair of response keys that either increased or decreased target luminance in step sizes of 0.2 cd/m2. To estimate PSEs, three such adjustments were performed for each surround luminance. Brightness induction strength was defined as the difference (in cd/m2) between fixed luminance of the reference circle (6 cd/m2) and the perceived (i.e., adjusted) luminance of the target (which was typically much higher).

Surround contrast illusion task

The stimulus display (Figure 1B) was similar to those used previously (Barch et al., 2012; Dakin et al., 2005; Chubb et al., 1989). Stimuli consisted of two circular patches (1.67° radius; 13.5° horizontal center-center separation) of spatial frequency filtered noise (1 cycle/° center frequency; 0.25 octave bandwidth). The Michelson contrast of the reference patch was fixed (20%) and was surrounded by a high-contrast noise annulus (6.67° radius, 97% contrast). The other patch was the target stimulus whose starting contrast was randomly chosen (10–30%). The positions (left or right) of reference and target stimuli were randomly assigned on each trial. Participants pressed one of two keys to indicate which patch appeared higher in contrast, and these responses were used to adaptively adjust the contrast of the target to match the apparent contrast of the reference stimulus.

Ebbinghaus size illusion task

This task was a variant of the Ebbinghaus illusion (Figure 1E). The fixed reference display consisted of a small circle (1.08° radius) surrounded by five evenly spaced, large circles (2.17° radius, 0.75° apart). The target stimulus was a small circle whose initial size was randomly chosen (0.92°–1.08° radius) and thereafter varied by the staircase procedure. The target and reference stimuli were presented 15° apart (center-center) and their positions (left or right) were randomly assigned on each trial. All stimuli were presented at 97% Michelson contrast. Participants pressed a key to indicate which of the two center circles was larger.

Surround Orientation Repulsion task

The stimulus display consisted of a small circular grating (0.5° radius, 50% contrast, 3 cycles/°) surrounded by a large, high-contrast annulus (4° radius, 97% contrast, 3 cycles/°), both of random phase (Figure 1D). The annulus orientation was fixed at 15° counter-clockwise from vertical whereas the center orientation was either 11° clockwise or counter-clockwise at the start of the task and thereafter determined by the staircase procedure. Participants used key presses to indicate whether the center patch appeared tilted clockwise or counter-clockwise relative to vertical.

Surround motion repulsion task

The stimulus display consisted of a stimulus moving within a small circular aperture (1° radius) that was surrounded by another stimulus moving within a large annulus (6° radius) (Figure 1C). Both stimuli moved at 3°/s and consisted of spatial frequency filtered noise (80% contrast; 1 cycle/° center frequency; 0.25 octave bandwidth). The surround motion direction was either 45° clockwise or counter-clockwise from vertical whereas the center motion direction was either 18° clockwise or counter-clockwise at the start of the task and thereafter determined by the staircase procedure. To avoid pursuit eye movements, stimuli were presented for 200ms and immediately replaced with a blank screen. Participants indicated whether the central motion direction was clockwise or counter-clockwise relative to vertical.

Procedure

Each experiment consisted of four blocks, starting with the control block (without context) and followed by three context blocks. Each block consisted of two interleaved 1-up/1-down staircases. The step size decreased after every two reversals. Each staircase converged after seven reversals and the average of the last four reversals was taken as the PSE estimate, i.e., the resultant PSE for each participant was an average of six staircases (two in control tasks). One exception was the brightness induction task where an adjustment method was used (described above). As all the tasks were subjective judgments about stimulus appearances, feedback was not provided. There was no time limit in making a response. The order of experiments was randomized for each participant. The entire battery took ~1–1.5 hours to complete. Before each task, participants performed five practice trials.

The magnitude of contextual effects was measured by the PSE estimates with surrounding context relative to the performance on the control condition, i.e., as the degree to which a participant’s perception changed as a result of adding the surrounding context. The units for luminance, contrast and size tasks were cd/m2, log10 contrast and arcmin, respectively. Orientation and motion repulsion were measured as angular repulsions in degrees.

Psychometric properties

To ensure that we can appropriately estimate contextual processing strength, we considered a number of psychometric issues: ceiling effects, floor effects and measurement reliability. None of the results approached stimulus-constrained ceilings that are inherent in our tasks (e.g., 90° repulsion in the orientation task). In fact, all results were considerably weaker than the stimulus-constrained ceilings. Theoretical floors also exist, and would be manifested as a "no context effect" for each task. However, as detailed in the Results, all of CO datasets exhibit strong context effects, leaving ample dynamic ranges to reveal weaker contextual effects in SZ. Finally, data for each task did not deviate from normality and equality of variance as assessed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene’s test, respectively.

To assess measurement reliability, we split each set of data into halves or thirds (see below) and correlated these partial datasets. For size and contrast tasks, we obtained 6 independent PSE estimates and, thus, we split the data in two halves. The CO/SZ split-half reliabilities were 0.90/0.90 and 0.84/0.83 for size and contrast experiments, respectively. For motion and orientation tasks, we obtained 3 pairs of measurements (with a pair consisting of two center directions/orientations). To estimate measurement reliability, we correlated the second and the third estimates. CO/SZ correlations were 0.69/0.79 and 0.58/0.82 for motion and orientation tasks, respectively. The modest correlation for CO in the orientation task is largely due to one CO subject who did not show a context effect in one measurement, without him/her the correlation is 0.71. Note that somewhat lower numbers in motion and orientation tasks are expected as only 2/3 of the data are used. Finally, CO/SZ correlations between second and third adjustment estimates in the brightness task were 0.87/0.88. In sum, we found reliabilities for SZ and CO to be comparable for each task, and relatively high. For SZ, all split-data reliabilities were between 0.79 and 0.90 (average = 0.844).

Results

Due to experimenter error, data for a few tasks were missing for two SZ; those tasks were size for one patient and motion, contrast, and brightness induction for both patients. However, their data on the other tasks were retained. Moreover, if a participant’s data fell three standard deviations or more from the group mean, his/her data were excluded. This resulted in exclusion of 8 datasets (1, 3 and 4 datasets in the contrast, orientation and motion tasks, respectively), accounting for ~3% of all data. Surround contextual effects were observed across all tasks and for both groups (one-sample t-tests, all p≤.001). Moreover, CO and SZ did not significantly differ in baseline conditions in which surround stimuli were absent (independent sample Welch’s t-tests, all p>0.05). This result shows that SZ had no problems accurately performing visual tasks in this study. Below, we report the results of each task separately (Figure 2), followed by combined analyses across tasks (Figure 3).

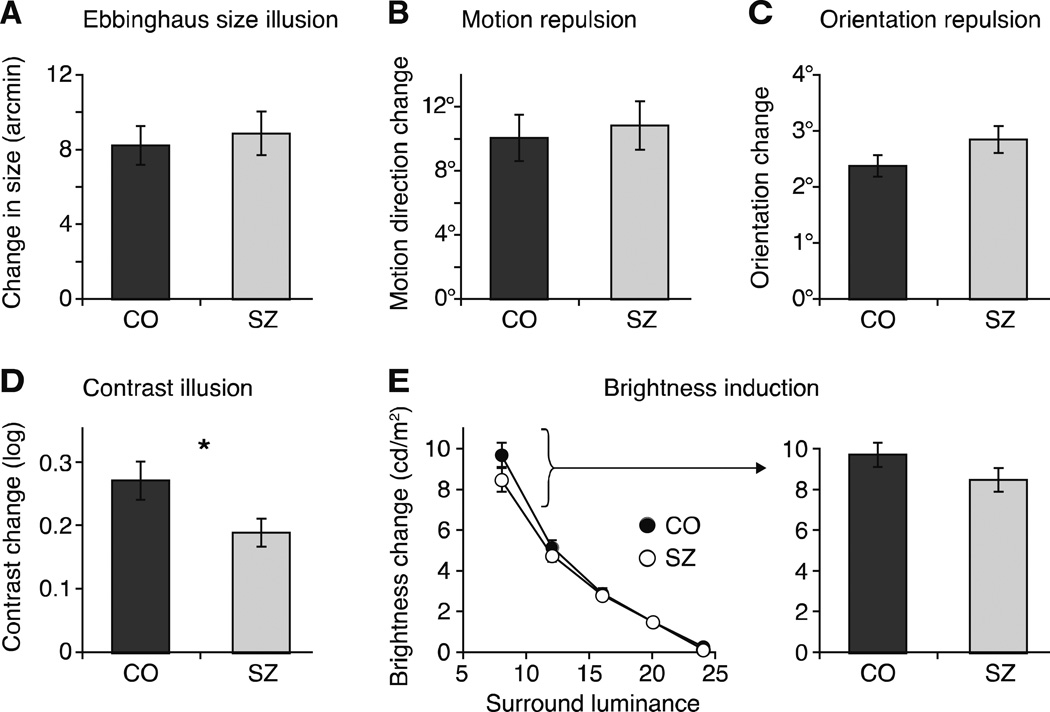

Figure 2. Results from five context modulation experiments.

Results from (A) Ebbinghaus size illusion, (B) motion repulsion, (C) orientation repulsion, (D) surround contrast illusion, and (E) brightness induction. In (E), data for five surround luminance levels are shown in the left panel. The right panel isolates the data for the condition with the strongest surround modulation (8 cd/m2), a condition included in Figure 3.

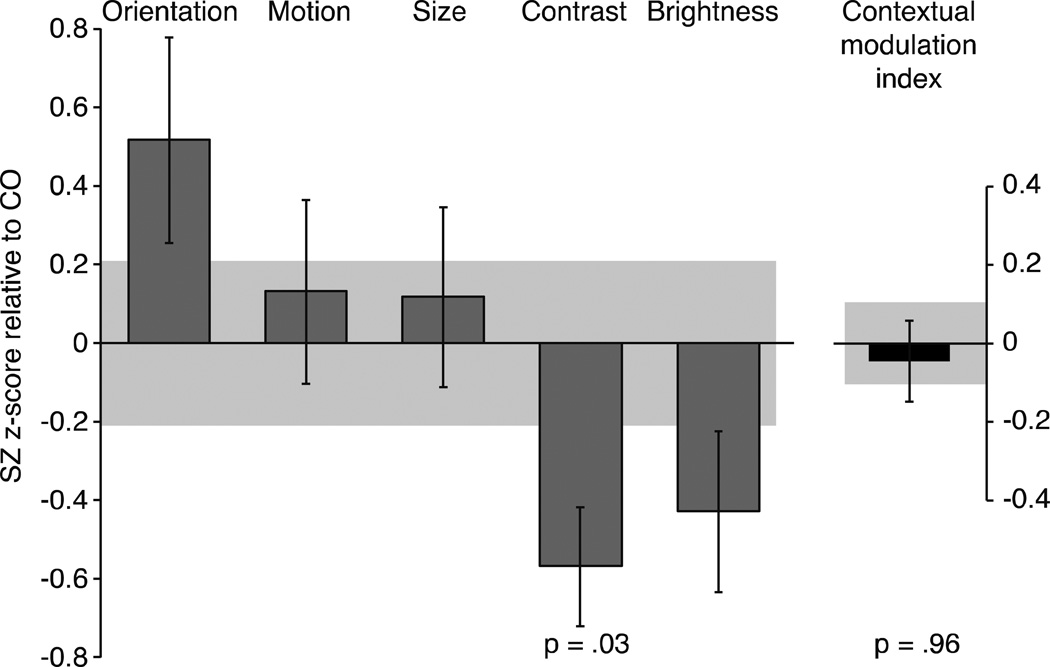

Figure 3. The magnitude of contextual effects in SZ.

For each task, the magnitude of contextual effect in schizophrenic patients (SZ) was converted into Z-scores relative to the mean and variance of controls (CO). The Contextual Modulation Index (CMI) was computed for each participant as the average z-score across tasks. Negative values indicate weaker contextual illusions in SZ, while positive values indicate stronger contextual illusions in SZ relative to CO. The only significant difference was weaker contextual modulation of contrast in SZ (t(42)=4.87, p=.03). CMI for SZ was not statistically different from 0 (z=-.048, p=.96). Error bars denote the SEM of the z-scores in the schizophrenia group and the shaded region denotes the SEM of the control group.

The contextual effects of size (t(50)=0.17, p=0.68, Cohen’s d=0.11, nco=23, nsz=29, Mco/Msz=8.9’/8.3’, SEMco/SEMsz=1.04’/1.16’), motion (t(45)=0.14, p=0.71, d=0.11, nco=21, nsz=26, Mco/Msz=10.11°/10.88°, SEMco/SEMsz=1.44°/1.51°), and orientation (t(47)=2.37, p=0.13, d=0.43, nco=23, nsz=27, Mco/Msz=2.39°/2.86°, SEMco/SEMsz=0.20°/0.24°) in SZ were not significantly different from those of CO, according to independent samples Welch’s t-tests. However, SZ did show a weaker contrast illusion than CO (t(42)=4.87, p=0.03, d=0.64, nco=23, nsz=27, Mco/Msz=0.27/0.19, SEMco/SEMsz=0.03/0.02). In the brightness induction task, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with surround luminance as the within-subjects factor and group as the between- subjects factor revealed a main effect of surround luminance (F(4,196)=324.3, Mean Square Error (MSE)=611.35, p<0.001) but no main effect of group (F(1,49)=1.24, MSE=8.87, p=0.27, d=0.31, nco=23, nsz=28, Mco/Msz=3.93/3.56 cd/m2, SEMco/SEMsz=0.26/0.22 cd/m2) nor an interaction between luminance and group (F(4,196)=1.7, MSE=3.17, p=0.16).

To examine the pattern of results across all contextual tasks, we normalized results for each task relative to CO group performance to derive z-scores (Figure 3). For the brightness induction task, we used the PSE estimate in the surround luminance condition that would evoke the strongest illusion (surround luminance of 8 cd/m2). Using a mixed model ANOVA with task and group as fixed factors, we found no significant main effect of group (F(1,50)=0.11, p=0.74) with a marginal main effect of task (F(4,49)=2.46, p=0.06). The combined analysis yielded a significant interaction between group and task (F(4,49)=2.53, p=0.05), indicating that the relative strength of contextual effects in SZ depended on which task was used. Figure 3 also shows that tasks where SZ were not significantly different from CO, when considered in isolation, are different from each other. Namely, in SZ, contextual modulation of orientation and motion are stronger than contextual modulation for both luminance (t(24)=2.7, p=0.01, d=0.75; t(25)=2.13, p=0.04, d=0.55, respectively) and contrast (t(24)=3.59, p=0.001, d=1.0; t(24)=2.27, p=0.03, d=0.62, respectively). While most of these analyses would not survive multiple comparisons correction, they indicate that the direction of findings in contextual processing studies of SZ will likely depend on which tasks are used.

To estimate a general measure of contextual processing in SZ, we derived a contextual modulation index (CMI) for each patient by averaging z-score across tasks (relative to CO). If patients show general weakening of contextual processing, then CMI should be negative. A positive CMI would indicate a general strengthening of contextual processing. The result, however, is z = −0.048, with an associated p-value of 0.96 (Figure 3). In other words, CMI is statistically zero. Furthermore, variance did not differ between groups (F(1,51)=0.43. p=0.52), ruling out the possibility that a lack of CMI differences is due to equal numbers of SZ with abnormally strong and abnormally weak CMIs.

We also examined inter-task correlations to test whether a weak contextual effect on one task would predict a weak contextual deficit on other tasks—a finding that would be expected by the presence of a common underlying deficit. However, no such correlations were found in SZ (all |Pearson’s r|<0.40, all p>0.06) nor in CO (all |r|<0.41, all p>0.07). Correlations did not reach significance even without applying Bonferroni correction. The strongest correlation in SZ performance was between orientation and motion tasks (r=0.39, p=0.07), whereas the rest of the inter-task correlations fell below 0.18 (p>0.38). This lack of inter-task correlations further suggests that our contextual tasks reflect largely distinct neural mechanisms.

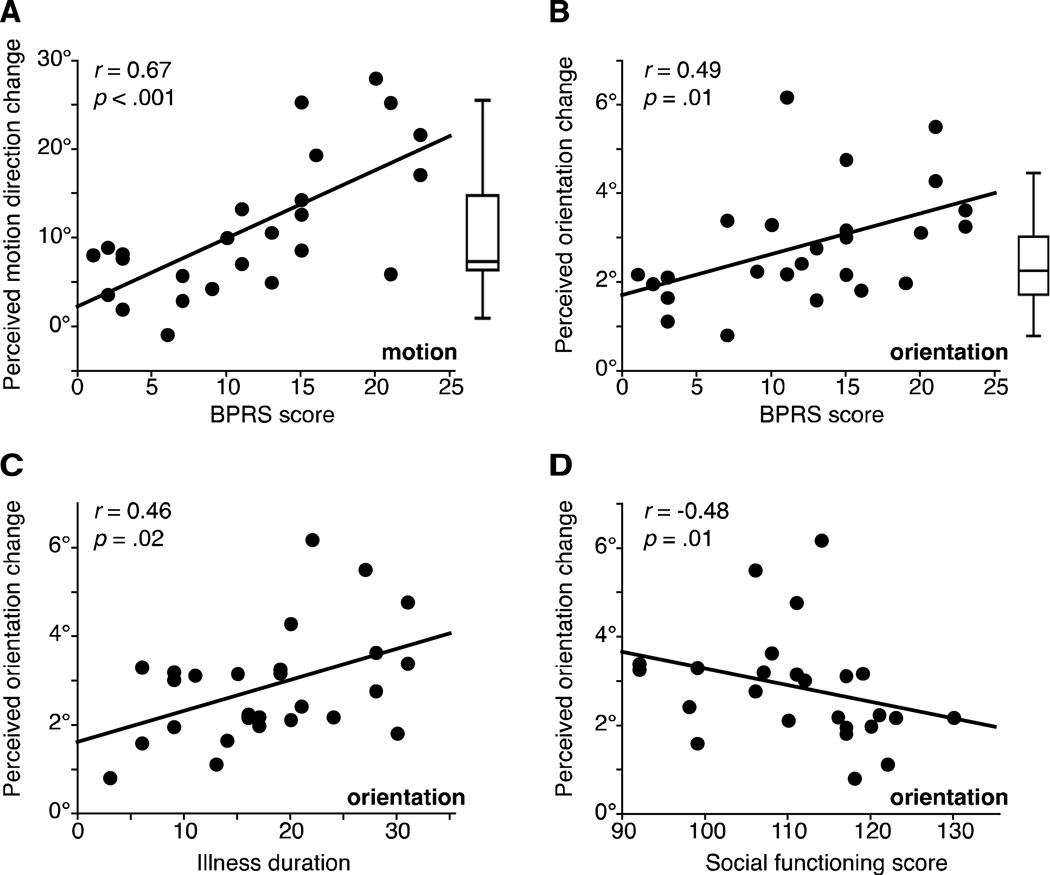

Lastly, we probed the relationships between the strength of contextual illusions and clinical symptoms in SZ. Results showed that the magnitudes of both orientation and motion illusions were positively correlated with BPRS, such that the severity of symptoms was associated with stronger illusory repulsion (Figure 4A & 4B; Spearman’s rho=0.50, p=0.008, n=27; rs=0.57, p=0.002, n=26, respectively). Orientation and motion illusions were correlated with negative (SANS; rs=0.46, p=0.02, n=27; rs=0.41, p=0.04, n=26, respectively) and positive symptoms (SAPS; rs=0.38, p=0.05, n=27; rs=0.44, p=0.02, n=26, respectively). Stronger orientation repulsion was further associated with longer illness duration (Figure 4C; rs=0.46, p=0.02, n=27), and lower social functioning (Figure 4D; rs=−0.48, p=0.01, n=25). The same analyses were applied after excluding 1 to 3 additional outliers based on symptoms scores, but still all correlations remained significant. In fact, correlations reported with BPRS and SANS grew stronger (rs=0.5~0.67, p≤0.001~0.01). BPRS, illness duration, and social functioning were not correlated (all |rs|<0.25, all p>0.20). Correlations with symptom scores and social functioning were not found with other tasks (all rs<0.32, all p>0.09). Furthermore, IQ (all rs<0.33, all p>0.09), education (all rs<0.24, all p>0.22), and CPZ (all |rs|<0.17, all p>0.44) did not correlate with performance on any tasks.

Figure 4. The relationship between clinical measures in SZ and magnitudes of orientation and motion repulsion effects.

The relationship between clinical measures in SZ and magnitudes of orientation and motion repulsion. Correlations between BPRS symptoms ratings and (A) perceived motion direction changes in the motion repulsion task and (B) perceived orientation changes in the orientation repulsion task. In both cases, SZ with higher BPRS scores were more likely to have stronger repulsion effects. Correlations remained significant when excluding one potential BPRS outlier (motion: r=.67, p<.001; orientation: r=.49, p=.01). Box plots illustrate the range of motion (left) and orientation (right) repulsion in CO (middle horizontal line denotes the median, the box boundaries represent the quartiles and the “whiskers” range from the minimum to maximum values). Correlations between magnitude of orientation repulsion and (C) social functioning scores and (D) illness duration. SZ with stronger orientation repulsion were more likely to have poorer social functioning and longer duration of illness. Overall, poorer clinical measures predicted stronger perceptual repulsion effects.

Discussion

This study examined contextual interactions in SZ across a broad range of visual tasks. SZ showed a weak contextual effect of contrast and, consequently, more accurate task performance relative to age- and gender-matched CO. On the other hand, the magnitude of contextual modulations associated with luminance, size, orientation, and motion were similar between groups. However, the strength of orientation-repulsion and motion-repulsion were related to clinical symptom severity and social functioning: stronger repulsion effects were associated with greater psychiatric symptoms, longer duration of illness, and poorer social outcome. Importantly, when considering the overall contextual modulation strength, the two groups could not be distinguished. In summary, our findings argue against a general contextual processing deficit in SZ and, instead, point to a more precise problem; abnormal contextual interactions in SZ are observed in specific visual sub-modalities and may be modulated by illness severity.

Contextual modulation of brightness

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate effects of surrounding context on perceived brightness in SZ. We found relatively intact brightness induction across several surround luminance values in SZ. The mechanisms responsible for contextual effects in brightness perception have been reported in retina, lateral geniculate nucleus and V1 (Rossi and Paradiso, 1999; Kinoshita and Komatsu, 2001). Thus, our results suggest that these subcortical and cortical mechanisms are relatively intact in SZ. A previous study found abnormal luminance discriminations in SZ (Delord et al., 2006). This result, however, is in contrast to normal luminance matching in the no-context control condition reported here.

Contextual modulation of contrast

Dakin et al (2005) was the first to report a weakened contextual contrast illusion in SZ. However, a recent study with a multi-site, large sample by Barch et al. (2012) did not replicate these results after excluding individuals who performed poorly on catch trials. Barch and colleagues argued that weakened surround contrast effects in SZ might be attributed to general impairments in attention. We, like Dakin et al., have found abnormally weak contrast modulations in SZ. Importantly, we observed this result paired with (1) normal baseline performance and (2) intact contextual effects on other tasks, leading us to exclude deficits in attention as a possible underlying cause. While our findings do not exclude a possibility of attentional confounds in Barch et al. (2012), we show that abnormally weak contextual processing can be observed even when there is no evidence for attentional impairments. It is likely that the unimpaired baseline performance in our study is due (1) unrestricted stimulus duration and (2) concurrent target/reference presentation. Previous studies (Barch et al., 2012; Dakin et al., 2005) used a two-interval procedure with relatively short stimulus durations (500ms), which may be more susceptible to attention deficits.

Our results extend other reports that demonstrate various impairments in contrast processing in SZ (Must et al., 2004; O’Donnell et al., 2002; Kantrowitz et al., 2009; but see Chen et al., 2003). For example, SZ fail to show typical contrast sensitivity modulations in presence of collinear flanking stimuli (Must et al., 2004). Surround contrast modulation is believed to reflect gain control mechanisms in V1 (Chubb et al., 1989; Lotto and Purves, 2001). Our results of relatively normal contextual modulation of luminance and impaired modulation of contrast together may suggest that abnormal visual processing in SZ begins at the level of V1. Furthermore, dysfunctional inhibitory circuitry in early visual cortex may be central to deficits in contextual contrast modulation. Yoon et al (2010) reported that SZ exhibited lower concentrations of GABA in visual cortex that was also predictive of weakened contrast gain control, as evidenced by reduced orientation-specific surround suppression. Importantly, these results could not be explained by a potential antipsychotic medication effect. We found that the CPZ equivalent dose, which indexes dopamine D2 binding, did not correlate with performance on the surround contrast (r = 0.12, p = 0.58) task or any other contextual task (all |r| < 0.17, all p > 0.44). Moreover, atypical antipsychotic medications reportedly have little influence on visual sensitivity (Chen et al., 2003). Although it seems unlikely that medication contributed significantly to the weakened contrast illusion in SZ, further research is needed to eliminate this possibility completely.

Contextual modulation of size

In our study, SZ showed a normal Ebbinghaus size illusion. In contrast, previous studies have reported that SZ (Uhlhaas et al., 2006) as well as psychometrically ascertained schizotypal individuals (Uhlhaas et al., 2004) showed a reduced size illusion effect. However, this result was only observed in a subset of individuals with disorganization symptoms or thought disorder. Our findings are consistent with those by Uhlhaas et al. (2004, 2006) as SZ participants in our study exhibited few if any symptoms of disorganization. It is also possible that SZ are only impaired in perceiving size illusions that are modulated by contrast. Kantrowitz and colleagues (2009) found that SZ differed from CO only on illusions whose strength varied with stimulus contrast, such as the Muller-Lyer and Ponzo illusions. On the other hand, the magnitude of the Ebbinghaus illusion does not vary with contrast (Hamburger et al., 2007). This theory dovetails nicely with our result of weak contextual modulation of contrast and relatively normal contextual modulation of size (using the Ebbinghaus illusion) in SZ.

Contextual modulation of motion and orientation

Motion perception deficits are well established in schizophrenia, and range from low-level motion deficits to abnormal processing of complex motions (Chen, 2011; Kim et al., 2011). Recent studies identified abnormal contextual modulation of moving stimuli (Tadin et al, 2006, Chen et al., 2008), although the exact nature of these deficits is still under debate. Using stimuli consisting of randomly moving dots, Chen et al. (2008) reported abnormally strong surround motion repulsion in mildly symptomatic SZ. In contrast, we previously found weaker surround suppression of moving grating stimuli (Tadin et al., 2006). SZ with strong negative symptoms outperformed CO on direction discriminations of large, high-contrast motions. This result indicates weaker center-surround antagonism in motion processing in SZ—a deficit that can be linked with disrupted processing in cortical area MT (Tadin et al., 2011). The present study, however, reveals stronger repulsive surround effects in those with greater symptom severity (Figure 4), consistent with results by Chen et al (2008). Importantly, our current task and the task used by Chen et al. (2008) measured subjective direction repulsion effects using stimuli that have clearly defined center and surround regions. In contrast, Tadin et al. (2006) used an objective direction discrimination task with briefly presented (< 100 ms) large stimuli. These substantial task and stimulus differences almost certainly indicate involvement of non-overlapping motion processes, and likely explain the different results in these studies. For example, neural processing of large, briefly presented stimuli involves mechanisms whose nature changes as the stimulus duration exceeds 100 ms (Churan et al., 2008). Another key difference between these studies is that clinical symptom scores (BPRS, SAPS & SANS) were much higher in Tadin et al (2006). This opens the possibility that the weakening of contextual interaction in motion perception is linked with the severity of symptoms. In fact, even among highly symptomatic patients in our previous study (Tadin et al., 2006), we found a positive correlation between clinical symptoms and abnormal weakening of surround suppression.

Turning to contextual orientation effects, Yoon et al. (2009 & 2010) reported that SZ exhibited weakened surround interactions in orientation in comparison to CO. Importantly, the measured contextual modulation was not a perceived change in stimulus orientation (as in the present study), but a perceived change of stimulus contrast. In other words, Yoon et al.’s task is close to our contrast modulation task (Figure 1A) – a task where we also find a weakened effect of surround contrast. In the present orientation task, we investigated the orientation repulsion illusion, which presumably arises from inhibitory interactions between neural populations tuned to different orientations (O’Toole and Wenderoth, 1977). Here, we find that stronger orientation repulsion is linked with increasing symptom severity and poorer social outcome. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of orientation repulsion in SZ.

Recently, Gold et al. (2012) examined the clinical correlates of three cognitive measures in a large cohort of SZ, including contextual contrast modulation. These measures were chosen for their potential use in clinical studies of SZ. They found that the surround contrast illusion failed to predict clinical symptoms or social functioning, which is in agreement with our study. On the other hand, we found that the magnitudes of both motion and orientation repulsion illusions strongly predicted the severity of a range of clinical symptoms and the orientation illusion further predicted social functioning. To ascertain the usefulness of these particular contextual illusions for clinical studies of SZ, further investigation will be necessary.

Clinical and theoretical implications

Our study was directly motivated by a number of studies revealing weaker contextual effects in schizophrenia (e.g. Dakin et al., 2005; Tadin et al., 2006). Results from these studies have been interpreted as evidence for a broad deficit in contextual processing that is manifested in weaker contextual effects. That interpretation, in turn, sparked interest in using measures of contextual processing for clinical trials in schizophrenia (Barch et al., 2012, Gold et al., 2012). These measures are scientifically and clinically appealing for several reasons. First, refined psychophysical methods provide powerful, sensitive, and objective tools for inferring brain function and functional neuroanatomy of visual cortex. Second, schizophrenia is characterized by a broad range of perceptual and cognitive deficits; demonstration of additional deficits in schizophrenic patients is not met with great skepticism. At the same time, Brendan Maher (1996) and others have argued persuasively for the implementation of tasks in which the “putative psychopathology should lead to superior performance” to rule out the shadow of the generalized deficit in schizophrenia. Thus, to fully understand the behavioral phenotype, it is necessary to specify both the impaired and the enhanced performances to describe the complete behavioral and cognitive profile of schizophrenia.

Why are our results important? We find no clear evidence for a general weakening of contextual visual processing. This finding is important for several reasons. First, it provides evidence against the widespread assumption that contextual processing is broadly impaired in schizophrenia. This commonly held belief that contextual processing represents a core problem in schizophrenia may be driven, in part, by the “file drawer effect” wherein published results are biased in favor of statistically significant results and against null results. Further exacerbating this problem is the fact that almost all these published studies were conducted on single visual modalities. Second, the results of our comprehensive evaluation of context effects are not meant to prejudge the question of whether contextual tasks should be used for clinical trials. Rather, our results underscore the need for more research. Finally, we report for the first time the profile of contextual processing in schizophrenia where we both confirm older results and report new abnormalities. In sum, our study shows clear evidence arguing against the notion of a generalized deficit in contextual processing and further demonstrates the specificity and complexity of contextual deficits in schizophrenia.

Conclusion

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of contextual interactions in SZ using a battery of well-established psychophysical tasks that tap into distinct visual mechanisms. Our findings provide strong, new evidence against a broad, general and unitary contextual processing deficit in schizophrenia. Given the current state of the literature, our findings represent a significant and important progress toward a more nuanced understanding of perceptual abnormalities in schizophrenia. Accurate perception forms the basis for our interactions with the external environment. Anomalous perceptual experiences, therefore, could lie at the core of the chronic difficulties confronted by individuals with schizophrenia as they attempt to navigate the complex, fast moving and constantly changing world.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institute of Health (MH073028, EY007135, EY001319, EY007125, and EY019295), P30 HD15052 to the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Research on Human Development and the World Class University Program through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (R31-10089).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Albright TD, Stoner GR. Contextual influences on visual processing. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:339–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, Iowa: The University of Iowa; 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Carter CS, Dakin SC, Gold J, Luck SJ, MacDonald AW, III, Ragland JD, Silverstein S, Strauss ME. The clinical translation of a measure of gain control: the contrast-contrast effect task. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(1):135–143. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddick O. Segmentation versus integration in visual motion processing. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90179-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10(4):433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Javitt DC. Early-stage visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18(2):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Silverstein SM, Dakin SC. Visual perception and its impairment in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Abnormal visual motion processing in schizophrenia: a review of research progress. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):709–715. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Bidwell LC, Holzman PS. Visual motion integration in schizophrenia patients, their first-degree relatives, and patients with bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2005;74(2–3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Levy DL, Sheremata S, Nakayama K, Matthysse S, Holzman PS. Effects of typical, atypical, and no antipsychotic drugs on visual contrast detection in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1795–1801. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Norton D, Ongur D. Altered center-surround motion inhibition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb C, Sperling G, Solomon JA. Texture interactions determine perceived contrast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(23):9631–9635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churan J, Khawaja FA, Tsui JM, Pack CC. Brief motion stimuli preferentially activate surround-suppressed neurons in macaque visual area MT. Curr Biol. 2008;18(22):R1051–R1052. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford CW. Perceptual adaptation: motion parallels orientation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(3):136–143. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JP, Servan-Schreiber D. Context, cortex and dopamine: A connectionist approach to behaviour and biology in schizophrenia. Psychological Review. 1992;99:45–77. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakin S, Carlin P, Hemsley D. Weak suppression of visual context in chronic schizophrenia. Curr Biol. 2005;15(20):R822–R824. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delord S, Ducato MG, Pins D, Devinck F, Thomas P, Boucart M, Knoblauch K. Psychophysical assessment of magno- and parvocellular function in schizophrenia. Visual Neuroscience. 2006;23:645–650. doi: 10.1017/S0952523806233017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler WS. Motion streaks provide a spatial code for motion direction. Nature. 1999;400(6739):65–69. doi: 10.1038/21886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Barch DM, Carter CS, Dakin S, Luck SJ, MacDonald AW, III, Ragland JD, Ranganath C, Kovacs I, Silverstein SM, Strauss M. Clinical, functional, and intertask correlations of measures developed by the Cognitive Neuroscience Test Reliability and Clinical Applications for Schizophrenia Consortium. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(1):144–152. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger K, Hansen T, Gegenfurtner KR. Geometric-optical illusions at isoluminance. Vision Res. 2007;47(26):3276–3285. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley DR. The schizophrenic experience: taken out of context? Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(1):43–53. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Butler PD, Schecter I, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Seeing the world dimly: the impact of early visual deficits on visual experience in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(6):1085–1094. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Park S, Blake R. Perception of biological motion in schizophrenia and healthy individuals: a behavioral and FMRI study. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Komatsu H. Neural representation of the luminance and brightness of a uniform surface in the macaque primary visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86(5):2559–2570. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Park S. Working memory impairments in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):599–611. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen GM, Young LT, Galway TM, Joffe RT. Backward masking task performance in stable, euthymic out-patients with bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2001;31(7):1269–1277. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher BM. Cognitive psychopathology in schizophrenia. In: Matthysse DL, Levy J, Kagan J, Benes F, editors. Psychopathology: The evolving science of mental disorder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 433–451. [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Janka Z, Benedek G, Kéri S. Reduced facilitation effect of collinear flankers on contrast detection reveals impaired lateral connectivity in the visual cortex of schizophrenia patients. Neurosci Lett. 2004;357(2):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HE. The National Adult Reading Test (NART): test manual. NFER-Nelson. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell BF, Potts GF, Nestor PG, Stylianopoulos KC, Shenton ME, McCarley RW. Spatial frequency discrimination in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(4):620–625. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole B, Wenderoth P. The tilt illusion: repulsion and attraction effects in the oblique meridian. Vision Res. 1977;17(3):367–374. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(77)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Lee J, Folley B, Kim J. Schizophrenia: Putting context in context. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2003;26:98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis. 1997;10(4):437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips WA, Silverstein SM. Convergence of biological and psychological perspectives on cognitive co-ordination in schizophrenia. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2003;26:65–138. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT, Harris JP. Perceptual changes in schizophrenia: a questionnaire survey. Psychol Med. 1985;15(4):859–866. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AF, Paradiso MA. Neural correlates of perceived brightness in the retina, lateral geniculate nucleus, and striate cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):6145–6156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06145.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaghuis WL, Thompson AK. The effect of peripheral visual motion on focal contrast sensitivity in positive- and negative-symptom schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(8):968–980. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadin D, Kim J, Doop ML, Gibson C, Lappin JS, Blake R, Park S. Weakened center-surround interactions in visual motion processing in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2006;26(44):11403–11412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2592-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadin D, Silvanto J, Pascual-Leone A, Battelli L. Improved motion perception and impaired spatial suppression following disruption of cortical area MT/V5. J Neurosci. 2011;31(4):1279–1283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4121-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Mishara AL. Perceptual anomalies in schizophrenia: integrating phenomenology and cognitive neuroscience. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(1):142–156. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Phillips WA, Mitchell G, Silverstein SM. Perceptual grouping in disorganized schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(2–3):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Silverstein SM, Phillips WA, Lovell PG. Evidence for impaired visual context processing in schizotypy with thought disorder. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Maddock RJ, Rokem A, Silver MA, Minzenberg MJ, Ragland JD, Carter CS. GABA concentration is reduced in visual cortex in schizophrenia and correlates with orientation-specific surround suppression. J Neurosci. 2010;30(10):3777–3781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6158-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Rokem AS, Silver MA, Minzenberg MJ, Ursu S, Ragland JD, Carter CS. Diminished orientation-specific surround suppression of visual processing in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(6):1078–1084. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]