Abstract

Invasive, genetically abnormal carcinoma progenitor cells have been propagated from human and mouse breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesions, providing new insights into breast cancer progression. The survival of DCIS cells in the hypoxic, nutrient-deprived intraductal niche could promote genetic instability and the derepression of the invasive phenotype. Understanding potential survival mechanisms, such as autophagy, that might be functioning in DCIS lesions provides strategies for arresting invasion at the pre-malignant stage. A new, open trial of neoadjuvant therapy for patients with DCIS constitutes a model for testing investigational agents that target malignant progenitor cells in the intraductal niche.

Research on the pre-malignant stages of breast cancer is beginning to address a fundamental question in human cancer biology: when does the invasive phenotype first arise? Recommendations from the 2009 US National Institutes of Health (NIH) breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) consensus conference1 have highlighted the clinical controversies that surround the treatment of DCIS (also known as intraductal carcinoma) and the need to understand the malignant nature of DCIS. Although some members of the NIH DCIS conference proposed that the word ‘carcinoma’ should be removed from the term DCIS, because DCIS is non-invasive and has a favourable prognosis, experimental studies of human and mouse DCIS lesions are showing the opposite: carcinoma precursor cells exist in these lesions, and the aggressive phenotype of breast cancer is predetermined early at the pre-malignant stage2–8. Investigators are uncovering the mechanisms through which DCIS and other pre-cancerous cells survive and adapt in the stressful, hypoxic, nutrient-deprived intraductal microenvironment4,9–12. Cyto-genetically abnormal DCIS progenitor cells have been isolated and propagated from fresh human DCIS lesions4 and mouse DCIS models3,7. Understanding the cellular processes that promote the survival of malignant progenitor cells in DCIS is providing strategies for killing DCIS cells.

In this Opinion article we highlight how the high-stress environment of the breast intraductal niche could spawn genetically abnormal malignant progenitor cells. On the basis of insights derived from studies of propagated spheroid-forming cells that were cultured from fresh DCIS lesions, a novel neoadjuvant therapy trial has been opened for patients with DCIS. The special design of this trial offers a means to screen investigational agents that suppress or kill malignant progenitor cells in pre-invasive breast lesions.

DCIS

DCIS is the most common type of non-invasive breast cancer in women13. The incidence of DCIS has increased sevenfold from the mid-1970s, primarily owing to increased detection through the widespread adoption of radiographic screening for invasive carcinoma. According to the 2009 NIH DCIS consensus conference, the incidence rate for women aged 50–64 years is 88 per 100,000 (REF. 1), and as of 1 January 2005 an estimated 500,000 women were living with a diagnosis of DCIS.

DCIS is defined as a proliferation of neoplastic epithelial cells within the closed environment of the duct, which is normally surrounded by myoepithelial cells and an intact basement membrane13–15. The outside perimeter of the basement membrane interfaces with the connective tissue stroma, immune cells, lymphatics and vasculature13 (FIG. 1). By definition, DCIS has not yet invaded beyond its intraductal origin, and might never invade neighbouring tissues. However, there is both clinical and experimental evidence to suggest that DCIS is a precursor lesion to most, if not all, invasive breast carcinomas8,13,16–18. It is generally accepted that women diagnosed with DCIS remain at high risk for the subsequent development of invasive carcinoma19–21. However, the proportion of DCIS lesions that would progress to invasive breast cancer if left untreated is unknown. Lesion size, degree of nuclear atypia and the presence of comedo necrosis are histopathological parameters that have been identified as affecting the risk of recurrence in the heterogeneous range of pre-malignant breast lesions13,22,23. DCIS is classified — based on the level of pathological characteristics and cytological abnormalities — into high-grade, intermediate-grade and low-grade lesions8,13,15, including the presence or absence of central necrosis18,24. The most aggressive type of DCIS is comedo-DCIS, which is frequently associated with central necrosis and micro-calcifications (small deposits of hydroxyapatite) and a high cytological grade13. Additional morphological forms of DCIS include cribriform (open spaces between the cords of cells), papillary or micropapillary (having finger-like projections) and solid. Many DCIS cases include at least two different architectural and molecular subtypes in the same breast8,13,15,16,18,22. Although there are many unanswered questions relating to the progression of DCIS to invasive breast cancer (BOX 1), the capacity of DCIS cells to survive in the hypoxic and nutrient-deprived environment of the intraductal niche is perhaps a crucial step towards malignancy.

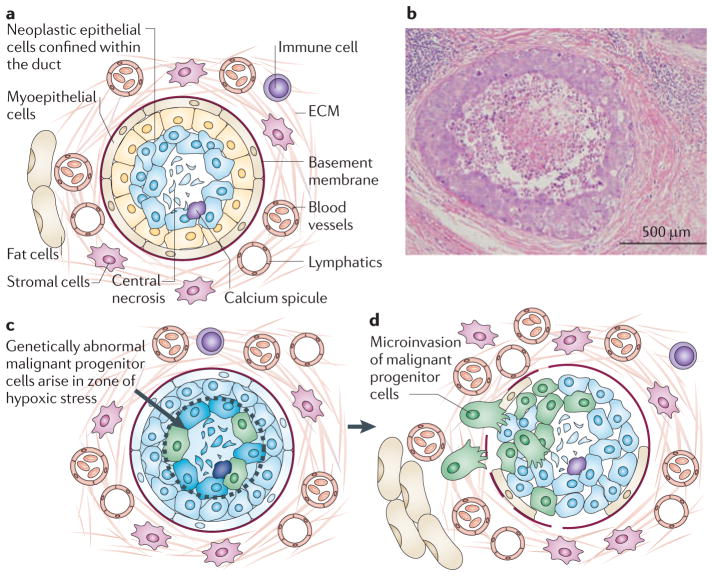

Figure 1. The stressful microenvironment of the intraductal niche may promote genetic instability.

a | This figure shows the microecology of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesions in the breast. DCIS neoplastic cells proliferate within the duct, which is bound by the basement membrane and a rim of myoepithelial cells on the lumen side of the basement membrane. The normal duct is composed of a single epithelial layer. By contrast, the DCIS lesion contains multiple layers of cells that accumulate inwards into the lumen. Outside the basement membrane the breast stroma contains the extracellular matrix (ECM), lymphatics, blood vessels, stromal cells, immune cells and fat cells. All of these components participate in the carcinogenic process by promoting or suppressing malignant progenitor cells that could arise within the mass of cells accumulating in the duct. b | Haematoxylin and Eosin stained section (original magnification x10) of a comedo-DCIS lesion, exhibiting central necrosis, stroma and lymphocytes. c | Necrosis occurs in the centre of the duct because these cells are the furthest radial distance from the oxygen and nutrients that diffuse from the vessels outside the duct. Proliferating cells within the intraductal microenvironment are under high stress because they are nutrient deprived, hypoxic, crowded and undergoing oxidative stress. d | Mammary pluripotent stem cells must adapt to survive in the high-stress microenvironment. Adaptation promotes the suppression of apoptosis in the face of genetic instability and could lead to the generation of genetically abnormal malignant progenitor cells before the onset of invasion. Invasion is associated with the loss of myoepithelial cells, periductal angiogenesis, fragmentation of the basement membrane and chemotaxis radially outwards.

Box 1. DCIS unanswered biological questions.

Although the transition fromin situto invasive cancer is central to the origin of the malignant phenotype, little is known about the time of onset or the triggering mechanism that switchesin situneoplastic lesions to overt invasive carcinoma in the human breast. Finding the answers to the questions listed below should help us to understand more about the timing and onset of malignant breast cancer.

Why do some ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesions progress to stromal invasion, but others apparently lie dormant? Are the subsets of DCIS lesions destined to progress fundamentally differently from those with a benign outcome?

Alternatively, do neoplastic cells with invasive potential arise frequently within DCIS lesions, but are held in check in lesions with a dormant clinical course?

DCIS cells that accumulate in the non-vascular intraductal space are under severe hypoxic and metabolic stress. Which mutations are selected for that promote the survival of DCIS cells to this stress? Are such survival pathways targets for chemoprevention or intervention?

Does adaptation to stress within the duct contribute to the carcinogenic process12,25,27?

The genetic abnormalities found in high-grade DCIS lesions are largely identical to the genetic abnormalities identified in the matched invasive carcinoma in the same patient2,5,6,13. Does this mean that the malignant genotype of breast cancer is predetermined at the pre-malignant stage? If so, what triggers the invasive cells to emerge?

If potentially invasive, cytogenetically abnormal neoplastic cells pre-exist in the intraductal DCIS lesion before the overt histological transition to invasive carcinoma, are these always the ultimate source of invasive metastatic carcinoma?

Survival in the intraductal niche

Survival and adaptation of pre-malignant cells within the stressful hypoxic and nutrient-deprived intraductal microenvironment might promote genetic instability and the selection of neoplastic cells with invasive potential. Indeed, metabolic and hypoxic stress within the tumour microenvironment is known to induce mutagenesis and genetic instability11,12,25–30. Adaptation to survival under stress can override normal cellular stress responses, leading to the persistence of genetically damaged cells and carcinogenesis11,12,27,29. Genotoxic, metabolic, hypoxic and oxidative stress engage stress-response programmes in normal cells10,12,22,29 (FIG. 2). For example, if DNA damage resulting from a genotoxic environment is substantial then such cells are likely to senesce or undergo programmed cell death. Pre-malignant and malignant cells have been proposed to either downregulate proteins that induce these pathways or upregulate pro-survival pathways9–12,22,26,28,29,31. Nevertheless, even if a cell can resist programmed cell death or senescence it will still not survive in a hypoxic, nutrient-deprived environment unless it can find alternative sources of energy for cellular functions, such as through autophagy, anaerobic respiration or increasing the efficiency of aerobic respiration9–11,22,25,26,28,32,33. To appreciate how DCIS might progress and circumvent stress-induced death or senescence, and use alternative sources of energy, we need to consider the nature of the stresses that affect DCIS cells.

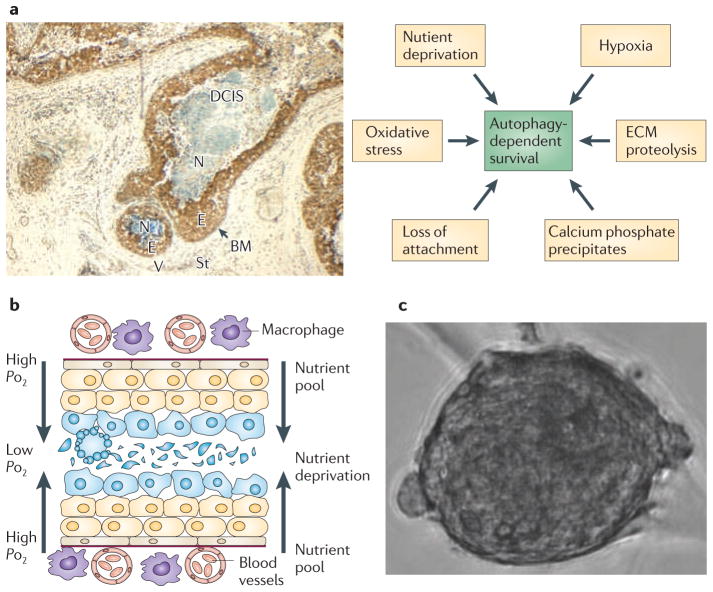

Figure 2. Autophagy and cell survival in DCIS lesions.

a | Human comedo-ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesion (original magnification x10) stained with antibodies to Beclin 1 shows upregulation of Beclin 1 (brown staining) in the viable rim of intraductal cells4 within the hypoxic ductal niche. Multiple types of stress that impinge on the DCIS cells directly contribute to the activation of autophagy (arrows; right side of figure). b | As abnormal DCIS cells accumulate within the duct many are pushed further from the source of oxygen and nutrients outside the duct. This sets up a gradient of stress that could be a ‘breeding ground’ for the mutational and cytogenetic abnormalities that drive breast cancer. Understanding how genetically abnormal DCIS cells arise and survive within the high-stress microenvironment provides targets for chemoprevention. c | Example of a human malignant precursor spheroid that can be propagated from fresh DCIS tissue4. BM, basement membrane; E, epithelial cells; ECM, extracellular matrix; N, necrosis; St, stroma; V, vessels.

DCIS cells must adapt to hypoxic stress within the duct

The vascular density of tissues is homeostatically regulated in all metazoan species to restrict the maximum distance between tissue cells and the nearest blood vessel. The average distance between vessels in tissues falls in the range of 25 to 50 micrometres34,35. The nearest distance from any DCIS cell to the vasculature on the other side of the basement membrane is determined by the DCIS lesion radius. The radii of DCIS lesions can be as great as 200 to 500 micrometres (15 to 60 cell diameters)13. This greatly exceeds the homeostatic limitations of blood vessel minimum density. Consequently, DCIS cells must adapt to severe hypoxic stress within the duct28,29,36–38, thereby promoting carcinogenesis11,12,39,40 (FIGS 1c,2b).

Multi-cellular spheroids that are grown in culture provide a model for the limitations of oxygen diffusion in a non-vascularized DCIS colony packed within the duct boundary of the basement membrane. Spheroids grown in culture exhibit central necrosis when the radius of the spheroid exceeds the maximum distance required for oxygen to diffuse in from the surface of the spheroid. The width of the viable rim of multi-cellular tumour spheroids that are grown in spinner culture was reported to be 150 micrometres over a wide range of spheroid diameters from 400 to 1,000 micrometres36,41,42. This distance is in the range of the average distance of vessels from the nearest area of necrosis that has been studied in solid tumours43. DCIS lesions normally expand to a diameter greatly exceeding the limitations of oxygen diffusion. Comedo-DCIS lesions show a central zone of necrosis with a sharp border of surrounding viable, neoplastic cells (FIGS 1,2). The viable rim can range from 5 to 25 cell layers thick24,37,38. Morphometric studies have shown that the mean diameter of the ducts containing DCIS with necrosis is 470 micrometres, compared with a mean diameter of 192 micrometres for DCIS without necrosis37. Necrosis is found in 94% of ducts larger than 180 micrometres in size compared with 34% of ducts less than 180 micrometres in size24. These findings support the existence of a hypoxic compartment in DCIS. The specific trigger of necrosis is unknown, but insufficient ATP production to maintain plasma membrane integrity could result in metabolic catastrophe44, which generates the typical comedo-DCIS central zone of cell lysis (FIGS 1,2). Dying cells produce soluble or endogenous factors that induce autophagy in surviving cells45. As discussed below, autophagy is one probable mechanism by which cells find an alternative source of ATP to avoid metabolic catastrophe11,28,46.

Avoiding hypoxia-induced apoptotic death

In hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) mediate the adaptive response to maintain oxygen homeostasis12,47. Under normal oxygen levels prolyl hydroxylases (PHD1–PHD3) use oxygen as a substrate to modify proline residues on the oxygen-dependent subunit HIFα. Hydroxylated HIFα is recognized by the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor protein, which is part of an ubiquitin ligase complex, and thereby targeted for proteasomal degradation48. Consequently, normal oxygen levels are associated with the degradation of HIFα, and, conversely, HIFα levels are increased by hypoxia. Increased HIFα levels correlate with hypoxia in solid tumours, which is associated with increased rates of patient mortality and treatment failure49. This, in part, might be due to the effect of hypoxia on the DNA-damage response. HIF-mediated adaptation to hypoxia can inhibit p53-mediated cell death in cells with DNA damage12. Moreover, hypoxic stress, independently of HIF, is associated with a decreased rate of repair of DNA damage, and increased cell invasion and metastatic potential25,27,39,40,50,51. Thus, in the presence of hypoxic stress, we can postulate that proliferating intraductal DCIS epithelial cells may adapt to survive in the presence of genetic mutations that drive tumour progression and facilitate invasion.

Avoiding stress-induced senescence

Abrogation of the retinoblastoma (RB) tumour suppressor pathway in DCIS cells can be an important survival strategy22. The dephosphorylation of RB in response to oxidative or metabolic stress in normal cells drives cell cycle arrest and senescence. It has been proposed that a subset of DCIS cells use various mechanisms to directly or indirectly compromise RB function10,17. One product of the CDKN2A locus, INK4A, is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) that is a negative regulator of D-type cyclins. Expression of INK4A inhibits RB phosphorylation and progression through the cell cycle. INK4A also functions in preventing centrosome dysfunction and genomic instability52. DCIS that exhibits high INK4A immunostaining and increased Ki67 expression (high proliferation index) identifies women who have reduced recurrence-free survival. Conversely, DCIS exhibiting high INK4A immunostaining in the absence of proliferation identifies women who have a low probability of subsequent disease10,22. Paradoxically, overexpression of INK4A can be associated with opposite biological responses. A cell with functional INK4A–RB signalling will initiate a stress-induced overexpression of INK4A resulting in a proliferative arrest that is characteristic of cellular senescence. By contrast, a cell with a compromised RB pathway will initiate a regulatory-induced overexpression of INK4A owing to unblocked negative feedback. In this situation the cells will disregard stress signals and will continue to proliferate10,22.

The repression of INK4A activity, accompanied by the inactivation of RB as a transcriptional repressor, leads to the overexpression of chromatin-remodelling proteins such as the polycomb proteins enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) and suppressor of zeste 12 homologue (SUZ12)53,54. These proteins are expressed in approximately 50% of DCIS lesions and are indicative of a poor prognosis in patients with invasive breast cancer55,56. Abnormalities in chromatin remodelling are thought to have a role in nuclear atypia and abnormalities in cell polarity, which are prominent features of DCIS pathology. In addition, when mammary epithelial cells were exposed to a variety of stresses, the inhibition of RB resulted in the persistence of DNA damage and could drive the expression of the pro-inflammatory protein cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2)9,57,58. COX2 expression can stimulate cell migration and angiogenesis, and has been reported to be upregulated in DCIS lesions in women with a high likelihood of subsequent breast cancer10,58. Therefore, another potential consequence of adaptation to stress in the intraductal niche is the promotion of genetic and epigenetic dysfunction through the INK4A–RB pathway.

Genetically abnormal DCIS cells

Breast cancer progression is thought to be a multistep process involving a continuum of changes from normal phenotype through hyperplastic lesions, carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma, to metastatic disease8,59 (BOX 2). In this model, additional genetic alterations are required before cells in a DCIS lesion can progress to an invasive and metastatic carcinoma. We propose that the traditional stepwise model of breast cancer progression has to be revised on the basis of new knowledge about cancer progenitor cells and cancer stem cells60. Recent data indicate that the aggressive phenotype of breast cancer is determined at the pre-malignant stage, much earlier than previously thought. Experimental approaches employing loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH), and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), as well as mutational screens, reveal that most of the genetic changes that underpin invasive breast cancer are evident in DCIS lesions2,3,5–8,59,61,62. Gene expression studies of patient-matched tissues, including atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), DCIS and invasive carcinoma, revealed that the various stages of disease progression are similar to each other at the level of the transcriptome2,5,6. These studies also show that DCIS lesions are more similar to the invasive breast cancer in the same patient compared with DCIS lesions from other patients2,5,6. Further support for the conclusion that primary genetic changes are present at the pre-malignant stage comes from studies of PIK3CA mutations and ERBB2 (also known as HER2) amplifications in DCIS lesions and matched invasive lesions from the same patient62. No significant difference in the frequency of PIK3CA mutations was found62 between the DCIS and the matched invasive cancer. In a separate study61, no significant differences were found between the gene amplification status of ERBB2, oestrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), cyclin D1 (CCND1) and MYC in DCIS compared with invasive breast cancer. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that the invasive phenotype of breast cancer is already genetically programmed at the pre-invasive stages of disease progression.

Box 2. Implications of the DCIS intraductal stress model to BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Understanding the origins of genetic instability in the stressful intraductal environment has relevance for chemoprevention and intervention strategies in women who carry a mutatedBRCA1 or BRCA2gene. The association between BRCA mutations and ductal carcinomain situ(DCIS) incidence and grade is still limited. Nevertheless, the existing data suggest that DCIS is equally as prevalent in patients who carry BRCA mutations as it is in women who have a high familial risk for breast cancer, but who are not BRCA mutation carriers. However, DCIS, like breast cancer in women with familial BRCA mutations, occurs at an earlier age102–104 and is often of a high grade (grade III)102,103. There is also an increased prevalence of pre-invasive lesions adjacent to invasive cancers in women with familial BRCA mutations105. All of these data suggest that BRCA mutation-associated breast cancer progresses through a DCIS precursor at an accelerated pace102–105 compared with breast cancer arising in patients without a familial BRCA mutation. Mutations inBRCA1are associated with genetic instability, increasing the risk of malignant transformation of cells106. In an animal model in whichBrca1is mutated specifically in the mammary epithelium, tumorigenesis occurs in mutant glands after a latency period. Introduction of aTrp53-null allele significantly reduces this latency period106. Hypoxia increases the stability of hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIFα) and confers resistance to p53-mediated apoptosis that is induced by genetic damage12. Consequently, the hypoxic state of the intraductal DCIS microenvironment will further compound the genetic instability of the DCIS cells in patients with BRCA mutations.

A mouse mammary intraepithelial neoplasia outgrowth (MINO) model of DCIS has also shown that gene expression and genomic changes are present in the initial, pre-malignant MINO lesions3, and these molecular profiles can be correlated to later phenotypes such as metastasis and responsiveness to oestrogen7. This mouse model of DCIS supports the concept that mammary carcinoma aggressiveness is pre-programmed in the pre-cancerous stem cell3. Dissociation of the MINO pre-cancerous lesions into three-dimensional spheroid culture revealed a bipotential capacity for myoepithelial and luminal differentiation with the formation of spheroids that could recapitulate the progression to invasive carcinoma following transplantation. By contrast, in comparison to the genetic changes that were found in the MINO DCIS lesions, the additional genetic changes that occur in the invasive carcinomas were subtle, with few consistent changes and no association with phenotype3,7. Progression from DCIS to invasive carcinoma was associated with few additional changes in gene expression and genomic organization in the MINO model. The MINO model data support the existence of a pre-cancer stem cell as the origin of invasive breast cancer3.

Isolation of human malignant DCIS cells

Given the data discussed above, can pre-malignant DCIS spheroid-forming cells be isolated from human DCIS lesions, and do these cells have characteristics that are associated with invasive carcinoma? Our laboratory investigated these questions using ex vivo organoid cultures of cells recently isolated from human DCIS lesions4. Spheroid-forming cells with an invasive and tumorigenic phenotype were propagated as eight independent patient cell lines. The human DCIS spheroid-forming cells exhibited cytogenetic abnormalities, including gain or loss of portions of chromosomes 1, 5, 6, 8, 13 and 17; invasion of autologous breast stroma in vitro; the ability to generate spheroids and duct-like three-dimensional structures in culture; increased expression of proteins associated with autophagy and pro-survival; and the capacity to generate tumours in non-obese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice4.

These cytogenetically abnormal progenitor cells4 were epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM)-positive and expressed stem cell markers. It has been postulated that dividing EPCAM-positive mammary progenitor cells can be subject to oncogenic mutations or genetic alterations at different stages during their differentiation60,63. The differentiation characteristics of specific invasive breast carcinomas could be a product of the different subtypes of the epithelial, ductal, alveolar or myoepithelial progenitor cell lineages8,22,60,63. We can postulate that such tumour-founding progenitor cells4,60,64 first arise in a pre-malignant stage such as DCIS. At this early point in the clinical progression of breast cancer the differentiated phenotype and the clinical aggressiveness might be fixed. Therefore, the tumour heterogeneity that is evident under the microscope and in the clinic may be predetermined at the pre-malignant stage3,5,6,8,22,60,65. If normal mammary progenitor cells become transformed as they adapt to survive in the high-stress microenvironment of the intraductal niche, then the biology of the resulting cancer is a product of the genetic instability, the suppression of apoptosis and the suppression of DNA repair that arise under stress.

When and why progenitor human cells with pre-existing invasive potential eventually grow out of the DCIS lesion is a central question. The absence of suppressive factors produced by the duct myoepithelial cells, the basement membrane or the stromal cells66,67 is likely to have a role. Suppressive factors might include myoepithelial cell–glandular epithelial cell interactions; soluble factors secreted by reactive or activated stromal cells, and mesenchymal cells or immune cells; and the barrier function and composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM)14,17,22,66–69. However, the activation of autophagy in the neoplastic epithelial cells as a result of stress might also have a central role.

Autophagy: energy source under stress

Autophagy is a pathway that is activated to promote survival in the face of hypoxic and nutrient stress11,32,33,62,70–74. Evidence indicates that autophagy is an emerging target for cancer therapy11,75–79. Autophagy is upregulated and co-localizes with areas of hypoxic stress in models of epithelial tumours28; autophagy-defective, immortalized mammary epithelial cells are more susceptible to cell death under conditions of metabolic stress26,28. DCIS growth is limited because of confinement within the duct and the absence of a blood supply. This state can trigger autophagy-mediated survival in the most metabolically stressed regions11,26,29. Thus, we can propose that autophagy is a major survival mechanism that is used by DCIS cells to persist and proliferate in the high-stress environment of the intraductal space4 (FIGS 2,3) and can be a main determinant of DCIS cell fate in response to metabolic stress11,26,29,44,46,80.

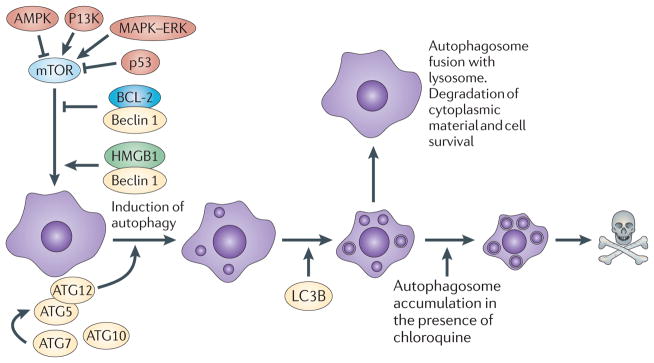

Figure 3. Upstream pathways that intersect with the autophagic pathway.

Autophagy is activated and regulated by various molecules that are known to be involved in oncogenesis, such as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), PI3K and p53. Autophagy is a catabolic process involving the degradation of the components of a cell by its own lysosomal machinery. Autophagy is a major mechanism by which a starving cell reallocates nutrients from unnecessary processes to more essential processes. The best-studied mechanism of autophagy involves the nucleation of a double-membrane vesicle around a cellular constituent. The resultant vesicle then fuses with a lysosome that contains acid proteases that degrade the contents, ultimately generating ATP for the cell. Chloroquine treatment blocks autophagy by interfering with the fusion of the autophagosome vesicle with the lysosome and by altering the acidic internal pH of the lysosome. ATG12, autophagy 12; HMGB1, high mobility group protein B1; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3β.

Four metabolic processes link autophagy to the survival and invasion of pre-malignant breast cancer. Hypoxia and nutrient stress are the first link11,28. As discussed above, proliferating ductal epithelial cells accumulating within the breast duct do not have access to the vasculature outside the duct. The activation of autophagy could divert the hypoxic DCIS cells away from apoptosis and thereby support the survival and growth of DCIS neoplastic cells within the lumen. Autophagy might also be integral to the removal of dead and dying or necrotic intraductal DCIS cells44,71,81,82.

Anoikis, the triggering of apoptotic cell death for cells that have been separated from their normal adhesion substratum, is the second link. Normal glandular epithelial cells require attachment to, or association with, the basement membrane ECM for continued survival. During ductal hyperplasia and dysplasia, epithelial cells are a substantial distance away from the peripheral basement membrane. Moreover, invading carcinoma cells can migrate into the stroma in the absence of a basement membrane anchor. Autophagy has been shown to be a key regulator of survival in cells that are deprived of an anchoring substratum, and may have an important role for cell survival in any anchorage-independent state83.

The third link is matrix degradation. High-grade DCIS, microinvasion and overt invasion are known to be associated with interruptions, remodelling and enzymatic breakdown of the basement membrane and the stromal ECM5,13,66. We can also postulate that autophagy might facilitate cell movement through areas of degraded matrix by processing matrix breakdown fragments that are phagocytosed by the migrating cells83.

Calcification is the fourth link to autophagy. Microcalcifications are seen in 90% of mammograms84–86, but microcalcifications of all types are associated with a broad range of breast lesions, and have only a 30–40% specificity for malignancy13,87. Nevertheless the shape, size and density of the microcalcification on a mammogram can be a specific indicator of the necrosis that is a characteristic of high-grade DCIS87–89. Pleomorphic, small calcifications (<0.5 mm) are also associated with high-grade and intermediate-grade DCIS. By contrast, microcalcifications that are restricted to the lobules are almost always associated with benign breast disease such as microcystic adenosis13,87,89. The chemical composition of most DCIS-associated microcalcifications is a subtype of calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, which is easily detectable by conventional light microscopy. The individual calcifications often appear concentrically layered, giving the impression that calcium deposition is accumulating over time. Calcium phosphate deposition is associated with the accumulation of necrotic cellular material13, and has been documented during the necrosis of fat cells in the breast13. As such, microcalcifications could provide an important clue about the developmental age of intermediate-grade and high-grade DCIS lesions. As hypoxia-induced necrosis might well precede calcium deposition, and calcium deposition occurs over time, we suggest that most intermediate-grade and high-grade DCIS lesions are subjected to hypoxic stress for a long period of time before diagnosis13,24. Thus, microcalcifications might be a signature of ongoing hypoxic stress and conditions that favour genetic instability. Although microcalcifications are a consequence and not a primary cause of DCIS they might contribute to the persistence of the DCIS lesions. Insoluble calcium has been shown to induce autophagy90, and may contribute to the local oxidative or metabolic stress within the duct.

Anti-autophagy: a new clinical strategy

The ability to isolate and grow human DCIS progenitor cells as spheroids in culture4 has made it possible to test whether autophagy has a role in DCIS progenitor cell survival4. DCIS spheroid-forming epithelial cells have increased expression of proteins associated with autophagy4,26,32,46 (FIG. 3) that persist in culture and in tumours generated by these cells in NOD/SCID mice4. Chloroquine, a clinically well-studied compound, is an orally administered small-molecule inhibitor that arrests the autophagy pathway by disrupting the cellular lysosomal function32,73 and altering the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Treatment of DCIS progenitor spheroids in culture with chloroquine reduced the expression of the autophagy-associated proteins, killed the DCIS progenitor spheroids and prevented tumorigenicity in NOD/SCID mice4. On the basis of these findings we suggest that autophagy promotes the survival of cytogenetically abnormal human DCIS malignant progenitor cells4. Consequently, the disruption of lysosomal function, or the abrogation of autophagy, constitute novel targets for treating DCIS. Understanding the regulation of autophagy provides a fertile field of therapeutic strategies for chemoprevention33,45,46.

The safety profile of oral chloroquine has been established through its use worldwide as an acute therapy for malaria91–95. Chloroquine can suppress N-methyl-N-nitrosurea-induced mouse breast carcinongenesis, increase the effectiveness of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment of primary chronic myeloid leukaemia stem cells, and has been proposed as a therapy for MYC-induced lymphomagenesis because it induces lysosomal stress and causes p53-dependent and caspase-independent cell death75,76,92,96. Treatment with chloroquine has also been proposed as a potential means to increase the effectiveness of tamoxifen in oestrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer by enhancing cell death in the sub-population of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells that emerges during treatment79. ER− breast cancer cells, in which tamoxifen therapy is contraindicated, may also exhibit chloroquine-induced cell death by blocking autophagy-dependent cell survival75,76,92. Thus, there is a rationale for the use of chloroquine in a patient with DCIS whose lesion is ER+ or ER−.

Chemoprevention strategies for the future

Tamoxifen is currently the only approved systemic treatment for preventing the recurrence of ER+ DCIS21,97,98. Tamoxifen was assessed in an investigational neoadjuvant study of ER+ DCIS where it was administered after diagnosis using a primary biopsy but before the commencement of standard-of-care surgical therapy99. This tamoxifen DCIS neoadjuvant study has established a precedent trial design for neoadjuvant therapy of DCIS.

We have recently opened a clinical trial of neoadjuvant therapy in patients with DCIS that provides a model system for testing any new and toxicity-tested compound for its ability to kill human pre-malignant DCIS progenitor cells. The trial will directly test the hypothesis that the disruption of autophagy-dependent lysosomal function by chloroquine is an effective treatment for DCIS. Chloroquine in this study is used as a short-term treatment after primary diagnosis but before surgical therapy. Previous animal studies have indicated that chloroquine treatment can enhance therapy-induced tumour apoptosis73,75,76, which can create increased numbers of necrotic cancer cells74, generating an inflammatory response. Theoretically, the resulting necrosis-induced inflammation over long-term chloroquine therapy may promote tumour progression74. We propose that a short exposure to chloroquine, before surgery, will prevent this potential side effect.

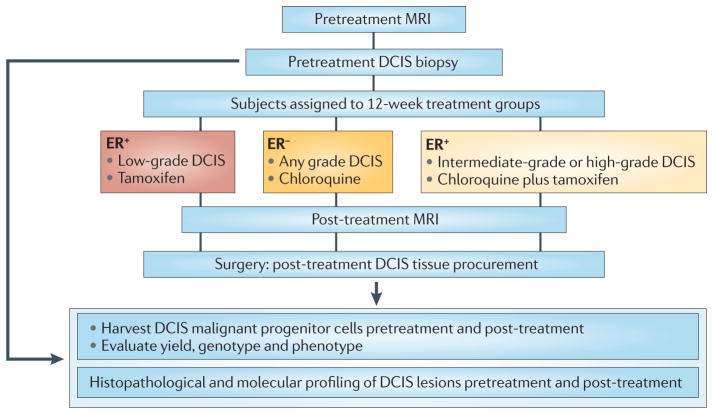

Patients with ER+ high-grade DCIS will receive standard-of-care tamoxifen plus chloroquine. Patients with ER− high-grade DCIS (expected to be approximately 50% of the high-grade DCIS cases) will receive chloroquine alone. Each patient is subject to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before enrolment and just before surgery (mastectomy or lumpectomy depending on the size and confluence of the primary DCIS lesion) 3 months after treatment (FIG. 4). Efficacy of the short-term 3-month therapy with either tamoxifen and chloroquine or chloroquine alone in this distinctive DCIS trial design will be uniquely measured directly at the molecular level. The genotype and the phenotype of harvested DCIS malignant progenitor cells, and the molecular histology of the DCIS lesion will be compared with MRI images before and after the 3-month course of therapy. This type of trial design could be used to test new agents for the ability to arrest breast cancer invasion at the pre-malignant stage100,101. We imagine a future in which a limited course of low toxicity therapy is administered to suppress or eradicate pre-malignant breast lesions in high-risk patients, even if the pre-malignant lesions are undetectable by standard imaging.

Figure 4. A neoadjuvant therapy trial for DCIS.

The Preventing Invasive Neoplasia with Chloroquine (PINC) trial (NCT01023477; see Further information) examines the safety and effectiveness of chloroquine administration to patients with low-grade, intermediate-grade or high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Patients with high-grade DCIS whose lesion is oestrogen receptor-positive (ER+) will receive standard of care tamoxifen plus chloroquine. Patients who are ER− will receive chloroquine alone. Patients with ER+, low-grade lesions will receive tamoxifen only. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will be carried out on each patient before enrolment and just before the standard-of-care surgical therapy, which will be mastectomy or lumpectomy depending on the size and confluence of the primary DCIS lesion. Effectiveness in this DCIS trial design will be uniquely measured directly at the molecular level in the DCIS tissue before and after treatment. The genotype, phenotype and proteome of the harvested malignant progenitor cells from the DCIS lesions, and the molecular histology of the DCIS lesion, will be compared with MRI images before and after a 3-month course of therapy.

Conclusion

New strategies for killing DCIS cells, which remove their ability to survive in the stressful intraductal space, have led to an ongoing neoadjuvant therapy trial for DCIS. Treating breast cancer before it can become invasive is analogous to the prevention of cervical cancer by treating pre-malignant cervical dysplasia, or to the prevention of colon cancer by the removal of pre-malignant polyps100,101. The knowledge gained from this new class of DCIS treatment trials might provide a basis for therapies aimed at suppressing or eradicating pre-malignant breast lesions.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program award, W81XWH-07-1-0377, to L.A.L. The authors would like to thank K. Edmiston for her role as clinical PI of the trial described in nure 4. The authors also thank B. Mariani and K. Tran, Genetics & IVF Institute, for genetic analysis of DCIS cells.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

FURTHER INFORMATION

ClinicalTrials.gov: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home

NIH Consensus Development Program: http://consensus.nih.gov/2009/dcisstatement.htm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Allegra C, et al. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2009;26:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro NP, et al. Evidence that molecular changes in cells occur before morphological alterations during the progression of breast ductal carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R87. doi: 10.1186/bcr2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damonte P, et al. Mammary carcinoma behavior is programmed in the precancer stem cell. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R50. doi: 10.1186/bcr2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espina V, et al. Malignant precursor cells pre-exist in human breast DCIS and require autophagy for survival. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma XJ, Dahiya S, Richardson E, Erlander M, Sgroi DC. Gene expression profiling of the tumor microenvironment during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R7. doi: 10.1186/bcr2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma XJ, et al. Gene expression profiles of human breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5974–5979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931261100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namba R, et al. Heterogeneity of mammary lesions represent molecular differences. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sgroi DC. Preinvasive breast cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fordyce C, et al. DNA damage drives an activin a-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in premalignant cells and lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:190–201. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauthier ML, et al. Abrogated response to cellular stress identifies DCIS associated with subsequent tumor events and defines basal-like breast tumors. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sendoel A, Kohler I, Fellmann C, Lowe SW, Hengartner MO. HIF-1 antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis through a secreted neuronal tyrosinase. Nature. 2010;465:577–583. doi: 10.1038/nature09141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boecker W. Preneoplasia of the Breast. Elsevier GmbH; Munich: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudjonsson T, Adriance MC, Sternlicht MD, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Myoepithelial cells: their origin and function in breast morphogenesis and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-9586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavassoli F. In: Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Tavassoli F, Devilee P, editors. IARC-Press; Lyon: 2003. pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claus EB, et al. Pathobiologic findings in DCIS of the breast: morphologic features, angiogenesis, HER-2/neu and hormone receptors. Exp Mol Pathol. 2001;70:303–316. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M, et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Landenberger M. Intraductal carcinoma of the breast: follow-up after biopsy only. Cancer. 1982;49:751–758. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820215)49:4<751::aid-cncr2820490426>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betsill WL, Rosen PP, Lieberman PH, Robbins GF. Intraductal carcinoma. Long-term follow-up after treatment by biopsy alone. JAMA. 1978;239:1863–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.239.18.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins LC, et al. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1778–1784. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher B, et al. Prevention of invasive breast cancer in women with ductal carcinoma in situ: an update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:400–418. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman HK, Gauthier ML, Tlsty TD. Premalignant breast neoplasia: a paradigm of interlesional and intralesional molecular heterogeneity and its biological and clinical ramifications. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:579–587. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagios MD. Heterogeneity of duct carcinoma in situ (DCIS): relationship of grade and subtype analysis to local recurrence and risk of invasive transformation. Cancer Lett. 1995;90:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)03683-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bussolati G, Bongiovanni M, Cassoni P, Sapino A. Assessment of necrosis and hypoxia in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: basis for a new classification. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:360–364. doi: 10.1007/s004280000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bindra RS, Glazer PM. Genetic instability and the tumor microenvironment: towards the concept of microenvironment-induced mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 2005;569:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kongara S, et al. Autophagy regulates keratin 8 homeostasis in mammary epithelial cells and in breast tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:873–884. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li CY, et al. Persistent genetic instability in cancer cells induced by non-DNA-damaging stress exposures. Cancer Res. 2001;61:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Assessing metabolic stress and autophagy status in epithelial tumors. Meth Enzymol. 2009;453:53–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson DA, et al. Hypoxia and defective apoptosis drive genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2095–2107. doi: 10.1101/gad.1204904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vakkila J, Lotze MT. Inflammation and necrosis promote tumour growth. Nature Rev Immunol. 2004;4:641–648. doi: 10.1038/nri1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paweletz CP, et al. Reverse phase protein microarrays which capture disease progression show activation of pro-survival pathways at the cancer invasion front. Oncogene. 2001;20:1981–1989. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine B, Ranganathan R. Autophagy: Snapshot of the network. Nature. 2010;466:38–40. doi: 10.1038/466038a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyng H, Sundfor K, Trope C, Rofstad EK. Oxygen tension and vascular density in human cervix carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1559–1563. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyer MJ, Barnard M, Hedley DW, Tannock IF. Regulation of intracellular pH in subpopulations of cells derived from spheroids and solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:890–897. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayr NA, Staples JJ, Robinson RA, Vanmetre JE, Hussey DH. Morphometric studies in intraductal breast carcinoma using computerized image analysis. Cancer. 1991;67:2805–2812. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910601)67:11<2805::aid-cncr2820671116>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinder SE. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): pathological features, differential diagnosis, prognostic factors and specimen evaluation. Mod Pathol. 2010;23 (Suppl 2):S8–S13. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mihaylova VT, et al. Decreased expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene Mlh1 under hypoxic stress in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3265–3273. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3265-3273.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young SD, Marshall RS, Hill RP. Hypoxia induces DNA overreplication and enhances metastatic potential of murine tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9533–9537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rotin D, Robinson B, Tannock IF. Influence of hypoxia and an acidic environment on the metabolism and viability of cultured cells: potential implications for cell death in tumors. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2821–2826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tannock IF, Kopelyan I. Influence of glucose concentration on growth and formation of necrosis in spheroids derived from a human bladder cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3105–3110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Primeau AJ, Rendon A, Hedley D, Lilge L, Tannock IF. The distribution of the anticancer drug Doxorubicin in relation to blood vessels in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8782–8788. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin S, DiPaola RS, Mathew R, White E. Metabolic catastrophe as a means to cancer cell death. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:379–383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang D, et al. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:881–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu S, et al. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nature Cell Biol. 2004;6:1221–1228. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hockel M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu F, White SB, Zhao Q, Lee FS. HIF-1α binding to VHL is regulated by stimulus-sensitive proline hydroxylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9630–9635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181341498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cuvier C, Jang A, Hill RP. Exposure to hypoxia, glucose starvation and acidosis: effect on invasive capacity of murine tumor cells and correlation with cathepsin (L+B) secretion. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1997;15:19–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1018428105463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young SD, Hill RP. Effects of reoxygenation on cells from hypoxic regions of solid tumors: anticancer drug sensitivity and metastatic potential. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:371–380. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDermott KM, et al. p16(INK4a) prevents centrosome dysfunction and genomic instability in primary cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e51. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bracken AP, et al. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 2003;22:5323–5335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynolds PA, et al. Tumor suppressor p16INK14A regulates polycomb-mediated DNA hypermethylation in human mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24790–24802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding L, Erdmann C, Chinnaiyan AM, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Identification of EZH2 as a molecular marker for a precancerous state in morphologically normal breast tissues. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4095–4099. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kleer CG, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11606–11611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crawford YG, et al. Histologically normal human mammary epithelia with silenced p16(INK4a) overexpress COX-2, promoting a premalignant program. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kerlikowske K, et al. Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:627–637. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simpson PT, Reis-Filho JS, Gale T, Lakhani SR. Molecular evolution of breast cancer. J Pathol. 2005;205:248–254. doi: 10.1002/path.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stingl J, Caldas C. Molecular heterogeneity of breast carcinomas and the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7:791–799. doi: 10.1038/nrc2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burkhardt L, et al. Gene amplification in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:757–765. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, et al. PIK3CA mutations mostly begin to develop in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bocker W, et al. Common adult stem cells in the human breast give rise to glandular and myoepithelial cell lineages: a new cell biological concept. Lab Invest. 2002;82:737–746. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000017371.72714.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boecker W, et al. Usual ductal hyperplasia of the breast is a committed stem (progenitor) cell lesion distinct from atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. J Pathol. 2002;198:458–467. doi: 10.1002/path.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liotta LA, et al. Metastatic potential correlates with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen. Nature. 1980;284:67–68. doi: 10.1038/284067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Witkiewicz AK, et al. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2023–2034. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen L, et al. Precancerous stem cells have the potential for both benign and malignant differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tlsty T. Cancer: whispering sweet somethings. Nature. 2008;453:604–605. doi: 10.1038/453604a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levine B, Abrams J. p53: the Janus of autophagy? Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:637–639. doi: 10.1038/ncb0608-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qu X, et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Samaddar JS, et al. A role for macroautophagy in protection against 4-hydroxytamoxifen-induced cell death and the development of antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2977–2987. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Autophagy facilitates the development of breast cancer resistance to the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White E, DiPaola RS. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5308–5316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amaravadi RK, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bellodi C, et al. Targeting autophagy potentiates tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced cell death in Philadelphia chromosome-positive cells, including primary CML stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1109–1123. doi: 10.1172/JCI35660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. Autophagy: an emerging target for cancer therapy. Autophagy. 2008;4:574–580. doi: 10.4161/auto.5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ostenfeld MS, et al. Anti-cancer agent siramesine is a lysosomotropic detergent that induces cytoprotective autophagosome accumulation. Autophagy. 2008;4:487–499. doi: 10.4161/auto.5774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schoenlein PV, Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Samaddar JS, Jackson WH, Barrett JT. Autophagy facilitates the progression of ERα-positive breast cancer cells to antiestrogen resistance. Autophagy. 2009;5:400–403. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McPhee CK, Logan MA, Freeman MR, Baehrecke EH. Activation of autophagy during cell death requires the engulfment receptor Draper. Nature. 2010;465:1093–1096. doi: 10.1038/nature09127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu L, et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature. 2010;465:942–946. doi: 10.1038/nature09076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fung C, Lock R, Gao S, Salas E, Debnath J. Induction of autophagy during extracellular matrix detachment promotes cell survival. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:797–806. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Evans A, et al. Lesion size is a major determinant of the mammographic features of ductal carcinoma in situ: findings from the Sloane project. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Evans AJ, et al. Screening-detected and symptomatic ductal carcinoma in situ: mammographic features with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1994;191:237–240. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Holland R, et al. Extent, distribution, and mammographic/histological correlations of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Lancet. 1990;335:519–522. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90747-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stomper PC, Connolly JL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: correlation between mammographic calcification and tumor subtype. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:483–485. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.3.1323923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evans AJ, et al. Correlations between the mammographic features of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and C-erbB-2 oncogene expression. Nottingham Breast Team. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)82937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hermann G, et al. Mammographic pattern of microcalcifications in the preoperative diagnosis of comedo ductal carcinoma in situ: histopathologic correlation. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1999;50:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gao W, Ding WX, Stolz DB, Yin XM. Induction of macroautophagy by exogenously introduced calcium. Autophagy. 2008;4:754–761. doi: 10.4161/auto.6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ducharme J, Farinotti R. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of chloroquine. Focus on recent advancements. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31:257–274. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Loehberg CR, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and p53 are potential mediators of chloroquine-induced resistance to mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:12026–12033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rahim R, Strobl JS. Hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and all-trans retinoic acid regulate growth, survival, and histone acetylation in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:736–745. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32832f4e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Savarino A, Lucia MB, Giordano F, Cauda R. Risks and benefits of chloroquine use in anticancer strategies. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:792–793. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70875-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wozniacka A, Cygankiewicz I, Chudzik M, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Wranicz JK. The cardiac safety of chloroquine phosphate treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: the influence on arrhythmia, heart rate variability and repolarization parameters. Lupus. 2006;15:521–525. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2345oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maclean KH, Dorsey FC, Cleveland JL, Kastan MB. Targeting lysosomal degradation induces p53-dependent cell death and prevents cancer in mouse models of lymphomagenesis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:79–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI33700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fisher B, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vogel VG. The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:51–60. doi: 10.1586/14737140.9.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fisher B, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kelloff GJ, Sigman CC. Assessing intraepithelial neoplasia and drug safety in cancer-preventive drug development. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7:508–518. doi: 10.1038/nrc2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O’Shaughnessy JA, et al. Treatment and prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia: an important target for accelerated new agent development. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:314–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hwang ES, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ in BRCA mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:642–647. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kwong A, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of Chinese patients with BRCA related breast cancer. Hugo J. 2009;3:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11568-010-9136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Smith KL, et al. BRCA mutations in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4306–4310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arun B, et al. High prevalence of preinvasive lesions adjacent to BRCA1/2-associated breast cancers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:122–127. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deng CX, Scott F. Role of the tumor suppressor gene Brca1 in genetic stability and mammary gland tumor formation. Oncogene. 2000;19:1059–1064. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]