Abstract

Objective

A longitudinal, prospective design was used to investigate a moderation effect in the association between early adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior 2 years later. A genetic vulnerability factor, a variable nucleotide repeat polymorphism (VNTR) in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4, known as 5-HTTLPR, was hypothesized to moderate the link between substance use at age 14 and risky sexual behavior at age 16. This VNTR has been associated with risk-taking behavior.

Design

African American youths in rural Georgia (N = 185) provided 2 waves of data on their substance use and sexual behavior. Genetic data were obtained via saliva samples.

Main Outcome Measures

Substance use and sexual risk behavior were assessed using youth self-report items developed for this investigation.

Results

Multiple regression analyses indicated that the presence of 1 or 2 copies of the short allele of the VNTR interacted with substance use to predict sexual behavior. Substance use had little effect on sexual behavior for youths without the short allele; this effect was greatly increased for youths with the short allele.

Conclusion

Genetic vulnerability affected the implications of early-onset substance use for later sexual behavior.

Keywords: African American, adolescence, genetics, sexual behavior, substance use

Nearly one-half of all new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States, including HIV, occur among adolescents and young adults (Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2004). Statistics indicate significant racial disparities in STI incidence; African Americans experience disproportionately higher rates than do members of other racial/ethnic groups (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007). African Americans account for 50% of HIV/AIDS diagnoses, and are 10 times more likely to receive AIDS diagnoses than are Caucasians. Almost two-thirds of individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS who are less than 25 years of age are African American. Although the number of new diagnoses significantly decreased among young adults from 1994 to 2003, diagnoses among adolescents remained stable (CDC, 2005). Rates of more common STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, are higher among African American youths, particularly among young women (Forhan et al., 2008). Among African Americans and adolescents, risk conferred by unprotected sexual intercourse with multiple partners accounts for an increasing proportion of new HIV cases and the majority of other STIs (CDC, 2007).

One of the most frequently cited risk factors for HIV-related sexual risk behavior during middle and late adolescence is substance use (Leigh & Stall, 1993). In particular, onset of substance use prior to age 15 has been linked with numerous HIV-related risk behaviors throughout adolescence (Guo et al., 2002; Tubman, Gil, Wagner, & Artigues, 2003; Whitbeck, Yoder, Hoyt, & Conger, 1999). Stueve and O’Donnell (2005) reported that early adolescent drinkers were more likely than abstainers to report unprotected sexual intercourse, intercourse with multiple partners, intoxication during intercourse, and pregnancy. Guo et al. (2002) found a prospective link between patterns of early adolescent substance use and subsequent sexual risks in young adulthood, including inconsistent condom use, intercourse with multiple partners, and substance use prior to intercourse. Similarly, a group led by Ellickson et al. (Ellickson, Tucker, & Klein, 2001) found problem behaviors, including pregnancy and parenthood by 12th grade, to be linked with early drinking and tobacco use.

The strength of the prospective associations between early adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior reported in these studies varies from low to moderate effects. This suggests that many early adolescents will experiment with substances but not experience an increased likelihood of risky sexual behavior. For example, Tubman et al. (2003) reported the percentages of youths who used substances in early adolescence and their level of sexual risk 2 years later. Although early substance use was a consistent risk factor, more than half of the early adolescents who used substances could be characterized as either at no risk or at low risk in their sexual behavior 2 years later. This heterogeneity in response to early substance use raises questions about possible moderators of this link.

Research on the occurrence of impulsive and aggressive behavior among substance users suggests that alterations in serotonergic neurotransmission may serve as a moderator of the link between early substance use and risky sexual behavior. Changes in serotonergic activity have been associated with impulsive behavior (Coccaro, 1992; LeMarquand, Pihl, & Benkelfat, 1994; Paaver et al., 2007) and poor performance on delay-of-gratification tasks (Bennett et al., 2002), factors that also increase the likelihood that youths will engage in risky sexual behavior (Dévieux et al., 2002; Robbins & Bryan, 2004). Variations in serotonergic activity are purported to explain individual differences in impulsive and aggressive behavior among adult substance users (Badawy, 1998; Hallikainen et al., 1999) and comorbid problems among adolescent substance use experimenters (Gerra et al., 2005).

In the present study, we hypothesized that variation in a specific polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) at the 5-HTT gene would moderate the influence of early adolescent substance use on later risky sexual behavior. The serotonin transporter protein (5-HTT) is involved in the presynaptic reuptake of serotonin to terminate and modulate serotonergic neurotransmission. The 5-HTT protein is the site of action of widely used reuptake inhibiting antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and traditional tricyclic antidepressants. A polymorphism has been identified in the promoter region for transcriptional control of SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR), which consists of different lengths of the repetitive sequence containing GC-rich, 20-23-bp-long repeat elements in the upstream regulatory region of the gene. A deletion/insertion in the 5-HTTLPR creates a short (s) allele and a long (l) allele (14- and 16-repeats), which alters the promoter activity. Three additional kinds of alleles (18-, 19- and 20-repeats) in 5-HTTLPR have been reported (Nakamura, Ueno, Sano, & Tanabe, 2000).

The s variant has been reported to be associated with lower basal and transcriptional efficiency of SLC6A4, resulting in lower serotonin uptake activity compared with the l variant (Heils et al., 1996). Allelic variation in genes encoding serotonin functioning have been associated with impulsive behavior, novelty seeking, and poor performance on delay-of-gratification tasks (Auerbach, Faroy, Ebstein, Kahana, & Levine, 2001; Kreek, Nielsen, Butelman, & LaForge, 2005; Suomi, 2004). Hamer (2002) reported a statistically significant association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and frequency of sexual activity among men. Men with at least one copy of the s variant had sex more frequently than did men without it.

Studies that include assessments of the serotonin transporter gene and psychosocial experiences support a focus on moderational processes (Uher & McGuffin, 2008). The presence of the s allele functions as a susceptibility factor that predicts poor outcomes, primarily in the presence of additional contextual risk factors (Olsson et al., 2005; Paaver, Kurrikoff, Nordquist, Oreland, & Harro, 2008). For example, Paaver et al. (2008) found that 5-HTTLPR status interacted with characteristics of family environments to predict disinhibition and impulsivity. In the present study, we hypothesized that 5-HTTLPR status would explain differential levels of sexual risk behavior in the presence of early adolescent substance use. We expected that substance use involvement would increase youths’ exposure to opportunities for risk taking; thus, we considered the number of substances a youth had tried rather than specific substances individually. Past research has demonstrated that measures indexing lifetime use of different substances are strong predictors of risk-taking behavior (Lowry et al., 1994; Santelli, Robin, Brener, & Lowry, 2001). We hypothesized that (a) substance use reported by youths at age 14 would predict their risky sexual behavior 2 years later at age 16, and (b) the influence of substance use would be significantly stronger for adolescents with a copy of the s allele at 5-HTTLPR than for those without a copy of the s allele.

Method

Data were collected as part of a family-based preventive intervention study (Brody et al., 2006). The data used in the present study were collected from families randomly assigned to the control condition, who did not take part in the intervention (N = 301). Substance use and sexual risk behavior data were obtained from follow-up assessments when the youths were 14 years old (called Wave 1) and again at age 16 (called Wave 2). Genetic data were obtained at Wave 2. Gene-environment hypotheses were tested with 185 youths who provided data at both time points, provided genetic data, carried either the ss, sl, or ll allele combination, and provided data on their sexual risk behavior and substance use. Attrition at each stage was unrelated to study variables. Details regarding the participants and procedures follow.

Participants

Youths were randomly selected from public school lists. Of the families contacted, 65% agreed to participate in the study. At Wave 1, youths’ mean age was 13.96 years (SD = .30); at Wave 2, their mean age was 16.04 (SD = .37). A majority (53.9%) lived in single-mother-headed households. The primary caregivers’ mean age was 37.8 years (SD = 7.45); 20.3% had not graduated from high school, 27.1% were high school graduates, 43.7% had some college education, and 8.9% had a bachelor’s or graduate degree. Mean household monthly income was $2,355.00 (SD = $1,693.34) and mean per capita monthly income was $559.80 (SD = $411.17).

Public schools in four rural Georgia counties provided lists of students, from which youth participants were selected randomly (Brody et al., 2006). Families were contacted and enrolled in the study by community liaisons who resided in the counties where the participants lived. The community liaisons were African American community members, selected on the basis of their social contacts and standing in the community, who worked with the researchers on participant recruitment and retention. The liaisons sent letters to the families and followed up the letters with phone calls to the caregivers. During the phone conversations, the community liaisons answered any questions that the caregivers asked. Each family was paid $100 after each assessment visit.

A total of 259 participants provided data at both Waves 1 and 2. Participation in both waves versus participation in one wave was not associated with any study variables. At Wave 2, families were asked to provide DNA from the youths; 212 (82%) agreed to DNA collection. Youths who provided genetic data were compared with those who did not. No differences emerged on any study variables.

Procedure

Trained African American field researchers conducted computer-based interviews in participants’ homes to gather data on youth substance use and sexual behavior. Youths were interviewed individually and privately; they were told that their answers were strictly confidential and would not be disclosed to anyone within or outside the family. For sensitive questions, youths were given a remote keypad with which to enter privately their responses after the interviewer read the question. Caregivers provided informed consent for their own and the youths’ provision of interview data and the collection of DNA from the youths; youths assented to their own participation.

DNA was obtained from youths using Oragene™ DNA kits (Genetek; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Youths rinsed their mouths with tap water, then deposited 4 ml of saliva in the Oragene sample vial. The vial was sealed, inverted, and shipped via courier to a central laboratory in Iowa City, where samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Genotype at 5-HTTLPR was determined for each sample as previously described (Bradley, Dodelzon, Sandhu, & Philibert, 2005).

Measures

Substance use was assessed with four items: “Have you ever [smoked cigarettes/drunk beer, wine, wine coolers, whiskey, gin, or other liquor/drunk three or more drinks on one occasion/smoked marijuana]?” rated dichotomously, 1 (yes) or 0 (no). Consistent with prior studies on early adolescent substance use onset (Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, & Murry, 2009; Santelli, Robin, Brener, & Lowry, 2001), these responses were summed. Cronbach’s alpha for the index was .55. This reliability estimate was comparable to those found in prior studies (see, for example, Lillehoj, Griffin, & Spoth, 2004) and reasonable, considering the small number of dichotomous items comprising the measure. Reliability and validity of self-reports for adolescent substance use have been previously evaluated and found to be acceptable (Elliott, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, & Canter, 1983; Smith, McCarthy, Goldman, 1995).

Youths’ sexual risk behavior during the past 12 months was assessed with three items. Youths reported number of sexual partners, estimated number of sex acts in which they engaged, and frequency of condom use during this period of time. Youths responded to the third item on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (every time) to 4 (never). Youths who had never had sex were assigned a 0, youths who reported using a condom every time they had sex were assigned a 1, and youths who reported not using a condom every time were assigned a 2. The three items were standardized and aggregated; Cronbach’s alpha for this index was .90.

Genetic risk was coded based on past research and the distribution of alleles in the sample. Of the total sample, 11 were homozygous for the s allele (ss), 78 were heterozygous (sl), and 129 were homozygous for the long allele (ll). Nine participants evidenced rare variants with a very long (vl) allele and results were inconclusive for 9 additional participants. Consistent with prior research (Hariri et al., 2002; Lesch, Bengel, Heils, & Sabol, 1996), genotyping results were used to form two groups of participants: those homozygous for the l allele and those with either 1 or 2 copies of the s allele. Other participants were excluded from the final analysis. The distributions for the ss, sl, and ll genotypes in the analyzed sample were 5%, 36%, and 59%, respectively; they were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, χ2(N = 218) = .0321, p = .23. Although recent studies suggest that in some samples ss and sl variants may function differently (Katsuragi et al., 1999), low base rates of ss participants in this and other African American samples precluded separate examination of these participants or examination of participants with vl allele variants. Additional analyses were conducted without the ss group, comparing sl and ll variants, the most common in this population.

Data Analyses

All data were analyzed using the regression procedure in SPSS 15.0. Missing data were deleted listwise; this resulted in a final sample of 185. Gender and Wave 1 substance use were controlled in the analyses. Because of low reliability in the sexual risk behavior index at Wave 1 due to low rates of youth sexual activity, we coded lifetime sexual intercourse at Wave 1 as 0 (never had intercourse) or 1 (had intercourse) and controlled this variable in the analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Prevalence rates for substance use and sexual risk behavior in the study sample are presented in Table 1. At age 14, substance use rates were generally low and similar for male and female youths. Sex differences between rates of marijuana use and sexual onset approached significance (p < .10), with male youths engaging in more of both behaviors than female youths. At Wave 2, male youths were more likely than female youths to be sexually active and to engage in risky sexual behavior. Approximately 40% of the youths (46% of males, 35% of females) had one or two copies of the s allele. No significant difference emerged between male and female youths on the presence of the short allele, χ2(1) = 2.69, p = .10.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Gender Comparisons for Substance Use and Sexual Behavior of the Study Population

| Measure | Total Sample

|

Male Youths

|

Female Youths

|

χ2(1) N = 185 |

t | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | M | SD | % | M | SD | % | M | SD | |||

| Wave 1, Age 14 | |||||||||||

| Tobacco use | 20.9 | 23.7 | 16.4 | 2.11 | |||||||

| Alcohol use | 43.2 | 39.0 | 47.0 | 1.65 | |||||||

| Binge drinking | 4.7 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 1.76 | |||||||

| Marijuana use | 5.0 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 3.10† | |||||||

| Sexual intercourse | 16.7 | 21.2 | 12.7 | 3.26† | |||||||

| Substance use index | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.90 | −0.72 | 0.89 | 0.15 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Wave 2, Age 16 | |||||||||||

| Sexual intercourse | 42.3 | 51.6 | 34.0 | 8.39* | |||||||

| Sexual risk index | 0.05 | 2.78 | 0.77 | 3.19 | −0.58 | 2.20 | 3.78** | ||||

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Multivariate Analyses

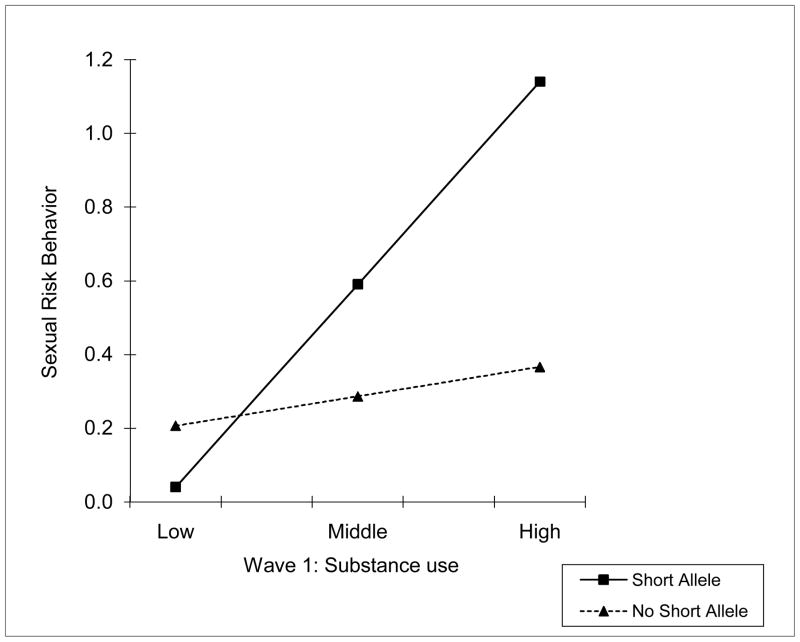

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses. Consistent with our hypotheses, substance use at Wave 1 predicted youths’ risky sexual behavior at Wave 2, net of the influence of gender and youths’ sexual initiation status at Wave 1. Also as expected, no main effect for allelic variation in 5-HTT on risky sexual behavior was detected. The interaction of 5-HTTLPR status and substance use at Wave 1, however, was a significant predictor of sexual behavior. The results were comparable when we repeated the analysis without the ss participants, representing a comparison between ll and sl variants. To interpret this interaction, we plotted low, middle, and high values of substance use at Wave 2 against sexual risk behavior scores for youths with and without the s allele (see Figure 1). For youths without the risk allele, substance use at Wave 1 had less influence on sexual risk behavior 2 years later. In contrast, for youths with a copy of the s allele at 5-HTT, substance use was strongly associated with later risk behavior. Supplemental regression analysis, with gender and sexual initiation status controlled, on youths without the risk allele indicated no significant association between substance use and later sexual risk behavior (t = .758, p = .450).

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis of Sexual Risk Behavior

| Sexual Risk Behavior | Model 1

|

Model 2

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | |

| Gender | 1.130 | .380 | .197 | .003 | 1.162 | .374 | .203 | .002 |

| Wave 1 intercourse status | 2.810 | .561 | .348 | .000 | 2.677 | .555 | .331 | .000 |

| Wave 1 substance use | .570 | .214 | .184 | .008 | .088 | .279 | .029 | .752 |

| 5-HTTLPR | −.286 | .383 | −.049 | .456 | −.317 | .378 | −.054 | .403 |

| Wave 1 substance use × 5-HTTLPR short allele (yes/no) | 1.033 | .395 | .232 | .010 | ||||

| R2 | .249 | .276 | ||||||

Figure 1.

5-HTTLPR status (presence vs. absence of a short allele) moderates the association between substance use and risky sexual behavior.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, substance use among rural African American youths age 14 was related strongly to high-risk sexual behavior 2 years later if they had a copy of the s allele of 5-HTT, but not otherwise. In the absence of this genetic vulnerability, there was no significant prospective association between substance use and sexual risk behavior. This study is among the first to demonstrate a gene-environment interaction (G × E) in the development of adolescent sexual risk behavior. These findings are consistent with several emerging lines of research investigating the joint contributions of genes and environment on adolescent risk behavior. Genetically informed studies of sexual risk behavior in adolescence indicate modest levels of heritability (Bricker et al., 2006; Dunne et al., 1997). Association studies of specific genotypes with complex phenotypes such as sexual risk behavior, however, rarely evince main effects and few are consistently replicated. G × E interaction effects provide an increasingly plausible mechanism for understanding how genetic variation and environments combine to contribute to risk behavior. In particular, polymorphisms in the 5-HTT gene have been shown to interact with environmental factors to forecast adolescent substance use (Nilsson et al., 2005) and mental health outcomes (Uher & McGuffin, 2008). These studies suggest that, in response to a range of experiences, vulnerable youths undergo alteration in serotonin neurotransmission, which is associated with heightened impulsivity and diminished self-regulation. The present research extends this literature to include the effects of early substance use on adolescent sexual risk behavior. Whereas early-onset substance use has been consistently identified as a risk factor for later sexual behavior, evidence from the present research suggests that, for youths without a genetic diathesis conferred by the s allele at the 5-HTTLPR, substance use has no prospective association with later sexual behavior.

The mechanisms that account for the interactive effects of early substance use and genetic variation at 5-HTT on risky sexual behavior currently are not well understood. Evidence supports a general risk-taking or novelty-seeking disposition underlying the link between substance use and sexual risk behavior. Accordingly, in the presence of specific contextual risk factors, the s allele may confer susceptibility to impulsivity. The intoxicating effects of substances combined with a susceptibility to risk behavior would likely lead to more sexual risk taking. Substance use in adolescence is also primarily a social activity marked by affiliations with risk-taking peers and low levels of parental supervision (DiClemente & Crosby, 2003). Accordingly, substance use may provide increased opportunities for sexual risk taking for youths with a genetic susceptibility to engage in risky behavior.

Some aspects of the present research should be noted as possible limitations. The study is generalizable to an important subset of youths, African Americans, but additional research is required to determine if the 5-HTTLPR moderates the substance use–sexual risk link in other racial/ethnic groups. Future research would benefit from investigation of mediating influences, particularly physiological mechanisms that clarify how youth with and without the 5-HTTLPR short allele respond to substance use. The exact relation of in vivo 5-HTT allele status to protein expression is uncertain. Recent studies suggest that the s and l variants may not have a simple dominant-recessive relationship; thus, sl and ss genotypes should be considered separately (Katsuragi et al., 1999). The ss variant, however, is rare in African American populations and we did not have sufficient base rates to examine it in this study. Some, but not all, research has suggested that a 5-HTT single nucleotide polymorphism, rs25531, may affect the expression of 5-HTTLPR variants (Hu et al., 2005; Philibert et al., 2007; Wendland, Martin, Kruse, Lesch, & Murphy, 2006). Future research is needed to address these issues. These cautions notwithstanding, the present study demonstrated that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism moderated the association between substance use in early adolescence and later risky sexual behavior.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by Award Number R01 AA012768 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and Award Number P30 DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We wish to thank Eileen Neubaum-Carlan for her invaluable assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Steven M. Kogan, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia

Steven R. H. Beach, Institute for Behavioral Research, University of Georgia

Robert A. Philibert, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa

Gene H. Brody, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia

Yi-fu Chen, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

Man-Kit Lei, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

References

- Auerbach JG, Faroy M, Ebstein R, Kahana M, Levine J. The association of the dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) and the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-HTTLPR) with temperament in 12-month-old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:777–783. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy AAB. Alcohol, aggression and serotonin: Metabolic aspects. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1998;33:66–72. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/33.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AJ, Lesch KP, Heils A, Long JC, Lorenz JG, Shoaf SE, Higley JD. Early experience and serotonin transporter gene variation interact to influence primate CNS function. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:118–122. doi: 10.1038/sj/mp/4000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SL, Dodelzon K, Sandhu HK, Philibert RA. Relationship of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and haplotypes to mRNA transcription. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;136B:58–61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Wadsworth SJ, Bryan A, Timberlake DS, DeFries JC. Genetic and environmental influences on age at sexual initiation in the Colorado Adoption Project. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:820–832. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Philibert RA, Chen Y-f, Murry VM. Prevention effects moderate the association of 5-HTTLPR and youth risk behavior initiation: G × E hypotheses tested via a randomized prevention design. Child Development. 2009;80:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kogan SM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brown AC, Wills TA. The Strong African American Families Program: A cluster-randomized prevention trial of long-term effects and a mediational model. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:356–366. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents (through 2003) 2005 Apr 22; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/graphics/adolesnt.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Vol. 17. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Impulsive aggression and central serotonergic system function in humans: An example of a dimensional brain-behavior relationship. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1992;7:3–12. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199200710-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dévieux J, Malow R, Stein JA, Jennings TE, Lucenko BA, Averhart C, Kalichman S. Impulsivity and HIV risk among adjudicated alcohol- and other drug-abusing adolescent offenders. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2002;14(Suppl B):24–35. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.7.24.23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Crosby R. Sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents: Risk factors, antecedents and prevention strategies. In: Adams G, Berzonsky M, editors. Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 573–605. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MP, Martin NG, Statham DJ, Slutske WS, Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. Genetic and environmental contributions to variance in age at first sexual intercourse. Psychological Science. 1997;8:211–216. doi:10.1111/j .1467-9280.1997.tb00414.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: Results from a 5-year follow-up. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:465–473. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976–1980. Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Institute; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, Berman S, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis among female adolescents in the United States: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004. Paper presented at the 2008 National STD Prevention Conference.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G, Garofano L, Castaldini L, Rovetto F, Zaimovic A, Moi G, Donnini C. Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism genotype is associated with temperament, personality traits and illegal drugs use among adolescents. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2005;112:1397–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0268-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:354–362. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallikainen T, Saito T, Lachman HM, Volavka J, Pohjalainen T, Ryynänen OP, Tiihonen J. Association between low activity serotonin transporter promoter genotype and early onset alcoholism with habitual impulsive violent behavior. Molecular Psychiatry. 1999;4:385–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000526. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/mp/journal/v4/n4/abs/4000526a.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer D. Genetics of sexual behavior. In: Benjamin J, Ebstein RP, Belmaker RH, editors. Molecular genetics and the human personality. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002. pp. 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D, Weinberger DR. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–402. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. doi:10.1126/science .1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stöber G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;66:2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Oroszi G, Chun J, Smith TL, Goldman D, Schuckit MA. An expanded evaluation of the relationship of four alleles to the level of response to alcohol and the alcoholism risk. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:8–16. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000150008.68473.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragi S, Kunugi H, Sano A, Tsutsumi T, Isogawa K, Nanko S, Akiyoshi J. Association between serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and anxiety-related traits. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:368–370. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, LaForge KS. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behaviors for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1035–1045. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMarquand D, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C. Serotonin and alcohol intake, abuse, and dependence: Clinical evidence. Biological Psychiatry. 1994;36:326–337. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj CJ, Griffin KW, Spoth R. Program provider and observer ratings of school-based preventive intervention implementation: Agreement and relation to youth outcomes. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:242–257. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Ueno S, Sano A, Tanabe H. The human serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) shows ten novel allelic variants. Molecular Psychiatry. 2000;5:32–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000698. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/mp/journal/v5/n1/abs/4000698a.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson KW, Sjöberg RL, Damberg M, Alm POF, Öhrvik J, Leppert J, Oreland L. Role of the serotonin transporter gene and family function in adolescent alcohol consumption. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000159112.98941.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson CA, Byrnes GB, Lotfi-Miri M, Collins V, Williamson R, Patton C, Anney RJ. Association between 5-HTTLPR genotypes and persisting patterns of anxiety and alcohol use: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study of adolescent mental health. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10:868–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001677. doi:10.1038/sj.mp .4001677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaver M, Kurrikoff T, Nordquist N, Oreland L, Harro J. The effect of 5-HTT gene promoter polymorphism on impulsivity depends on family relations in girls. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32:1263–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaver M, Nordquist N, Parik J, Harro M, Oreland L, Harro J. Platelet MAO activity and the 5-HTT gene promoter polymorphism are associated with impulsivity and cognitive style in visual information processing. Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0867-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philibert RA, Sandhu H, Hollenbeck N, Gunter T, Adams W, Madan A. The relationship of 5HTT (SLC6A4) methylation and genotype on mRNA expression and liability to major depression and alcohol dependence in subjects from the Iowa Adoption Studies. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;147:543–549. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins RN, Bryan A. Relationships between future orientation, impulsive sensation seeking, and risk behavior among adjudicated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:428–445. doi: 10.1177/0743558403258860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Robin L, Brener ND, Lowry R. Timing of alcohol and other drug use and sexual risk behaviors among unmarried adolescents and young adults. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33:200–205. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2673782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, O’Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:887–893. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi SJ. How gene-environment interactions shape biobehavioral development: Lessons from studies with rhesus monkeys. Research in Human Development. 2004;1:205–222. doi: 10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Gil AG, Wagner EF, Artigues H. Patterns of sexual risk behaviors and psychiatric disorders in a community sample of young adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:473–500. doi: 10.1023/A:1025776102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the aetiology of mental illness: Review and methodological analysis. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13:131–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002067. doi:10.1038/sj.mp .4002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3181210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland JR, Martin BJ, Kruse MR, Lesch KP, Murphy DL. Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs25531. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11:224–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Yoder KA, Hoyt DR, Conger RD. Early adolescent sexual activity: A developmental study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:934–946. doi: 10.2307/354014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]