Abstract

Hormones influence countless biological processes across the lifespan, and during developmental sensitive periods hormones have the potential to cause permanent tissue-specific alterations in anatomy and physiology. There are numerous critical periods in development wherein different targets are affected. This review outlines the proceedings of the Hormonal Programming in Development session at the US-South American Workshop in Neuroendocrinology in August 2011. Here we discuss how gonadal hormones impact various biological processes within the brain and gonads during early development and describe the changes that take place in the aging female ovary. At the cellular level, hormonal targets in the brain include neurons, glia, or vasculature. On a genomic/epigenomic level, transcription factor signaling and epigenetic changes alter the expression of hormone receptor genes across development and following ischemic brain insult. In addition, organizational hormone exposure alters epigenetic processes in specific brain nuclei and may be a mediator of sexual differentiation of the neonatal brain. During development of the ovary, exposure to excess gonadal hormones leads to polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Exposure to excess androgens during fetal development also has a profound effect on the development of the male reproductive system. In addition, increased sympathetic nerve activity and stress during early life have been linked to PCOS symptomology in adulthood. Finally, we describe how age-related decreases in fertility are linked to high levels of nerve growth factor (NGF), which enhances sympathetic nerve activity and alters ovarian function.

Keywords: Gonadal hormones, Development, Aging, Brain, Ovary, Stress

Gonadal steroid hormones act as critical trophic factors necessary for the normal development of many biological systems. This review summarizes data presented during the Hormonal Programming in Development session at the US-South American Workshop in Neuroendocrinology that illustrate the necessity of hormones, and the critical timeframes for hormone exposure in development of the brain and gonads. We describe mechanisms by which hormones, neurotransmitters, and other signaling factors influence sexual differentiation of the brain as well as abnormal development of the ovary and male reproductive system. We also describe how alterations in sympathetic nerve activity are critical in the development of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and how growth factor signaling contributes to reproductive senescence.

Hormonal programming in the brain during development: A walk through multiple stages and processes

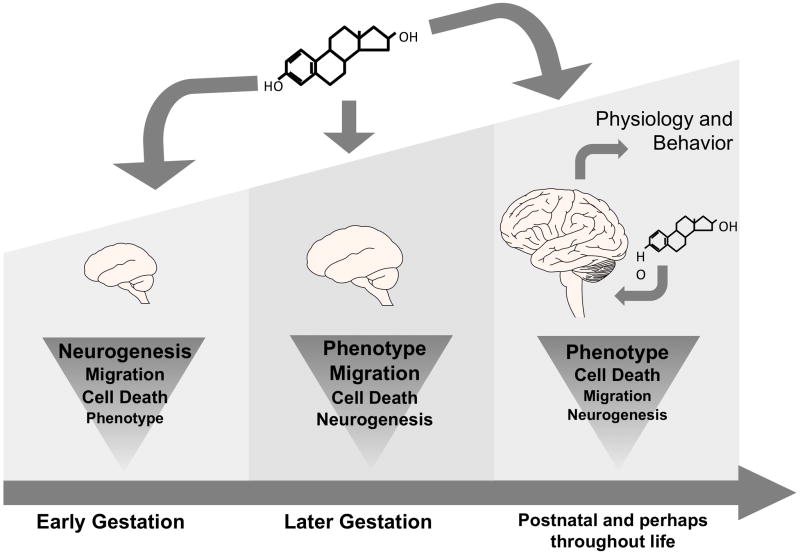

Although the majority of sexual dimorphisms are characterized in mature animals, mechanisms for their generation often operate during critical perinatal periods. Both genetic and hormonal factors likely contribute synergistically to the physiological mechanisms underlying the ontogeny of sexual dimorphisms in the brain. Relevant mechanisms may include neurogenesis, cell migration, cell differentiation, cell death, axon guidance and synaptogenesis. In addition, a new mechanism for consideration involves neurovascular development. Each of these mechanisms may be tied to select stages of development although they may also be present to differing degrees at all stages of life (Figure 1). Sex differences in the brain are often most prominent in brain regions associated with reproductive functions, although differences in regions associated with cognition, learning, and memory are also critical to sex differences in behavior [1]. The value of understanding developmental sexual differentiation lies in the presence of sex differences in a number of high impact disorders ranging from cardiovascular disease to obesity and mood disorders.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of developmental events occurring during hormonal programming of the brain. The processes of neurogenesis, migration, cell death, and phenotypic selection occur throughout gestational development and, most of these processes continue to occur throughout the animal’s lifespan. Hormones of placental origin during early gestation, and gonadal origin during later gestation and postnatal life have been shown to influence each one of these important developmental processes, permanently programming the neural substrate.

The majority of sex differences that arise in development are the direct consequence of hormone actions. Most of our knowledge of how the brain is sexually differentiated has been the result of work in rodents. From a few days prior to birth (~ embryonic day 18 (E18)) to a few days after birth (~ postnatal day 10 (PN10)) the rat brain is vulnerable to both defeminization and masculinization by gonadal steroid hormones [2, 3]. This short temporal window elegantly coincides with the release of high levels of circulating testosterone from the developing testes, which permanently defeminizes and masculinizes the male brain. The female brain, often referred to as the “default” sexual phenotype, is protected from defeminization and masculinization by circulating estrogens of maternal origin by the hormone binding protein alpha-fetoprotein [4]. Testosterone, which circulates at higher levels in males, is aromatized to estradiol within neurons in several specific regions of the developing brain [5]. Estradiol is an essential trophic factor in both sexes but at higher levels masculinizes the neural substrate via both rapid nongenomic and classic genomic actions altering neuronal and glial, structure, function, gene expression patterns, among other critical anatomical and physiological parameters (Reviewed in [6]). Although estrogens are the main organizers of the rodent brain, androgens play key roles in sexual differentiation of the primate brain and are important in other species as well [7, 8]. The early establishment of sex differences in the brain allows adult levels of circulating hormones to activate the expression of sex-specific physiologies and behaviors.

The physiological effects of estradiol in target tissues are largely mediated by intracellular receptors and membrane receptors. The two intracellular receptors, ERα and ERβ [9–13] are both expressed throughout the brain with distinct patterns in different brain regions and with varying levels of expression during development [14–18]. Understanding the dynamic expression and regulation of these receptors provides insight into the molecular processes essential for normal brain development as well as hormonally-mediated sexually differentiation of the brain.

ERα protein and mRNA levels change dramatically during postnatal brain development [14, 19, 20]. High levels of estradiol binding are observed in non-hypothalamic regions of the brain such as the cortex and hippocampus during the first two weeks of life [21–23]. This expression declines as animals approach puberty. In studies in rats and mice, ERα mRNA expression was shown to correlate with the changes in estrogen binding in the hippocampus and cortex [18, 24]. The Wilson lab examined ERα mRNA expression in the mouse isocortex during postnatal development by quantitative real-time RT-PCR and determined that the decline in ERα mRNA expression begins during the second week of life [18]. ERα is also expressed in the prefrontal cortex, an area that may be responsible for cognitive processes, and is potentially modified by estradiol. The Wilson lab saw a similar decline in ERα mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex, however with a significant sex difference on PND10. The significance of this sex difference at this age is unknown in rodents, but may play a role in sex differences and hormonal influences observed in cognitive behaviours associated with the prefrontal cortex [25–27]. Consistent with other studies [23, 24], the Wilson lab also found that ERα mRNA in the whole hippocampus declines during development.

The mechanisms of how the ERα gene is regulated during development are just now being uncovered [28–30]. Understanding these mechanisms will be critical for understanding how gene expression is regulated at any developmental time point. Following brain injury the surviving neurons appear to revert to a profile of gene expression of early development [31, 32]. The Wilson lab has observed this in female rats following ischemia [33]. The molecular factors that control ERα mRNA expression at the transcriptional levels are not well known. Some transcription factors such as Stat5 in the JAK-Stat signal transduction pathway have been shown to regulate ERα expression [30]. Inhibition of Stat5 binding abolishes the ability of prolactin to increase ERα gene expression indicating its role in the hypothalamus. It is possible that this signal transduction pathway plays an important role in regulating ERα mRNA in the cortex, as the expression of Stat1 and Stat5 actually increase during postnatal development [34]. It is likely that additional mechanisms of ERα mRNA regulation in the brain will be found.

Although it is well known that activation of ERα and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) contribute to masculinization and defeminization of the neonatal brain [35, 36], large gaps remain in our collective knowledge of how sexual differentiation of the brain is achieved. To complicate our understanding of estrogenic mechanisms on the cellular level, estrogen receptors may lie in cell nuclei or in membranes (endoplasmic reticulum or plasma membrane). In addition, understanding the molecular mechanisms of steroid action has become increasingly complex due to the growing number of estrogen binding proteins that have been identified in multiple model systems. In addition, some sex differences may arise due to direct genetic factors [37, 38], and others may be best revealed after genetic or environmental disruption [39, 40].

The development of some sex differences in the brain can be linked to neuronal origin. The next step in neuronal development following neurogenesis is migration and here too there are apparent sex differences that are likely controlled by both hormone dependent and independent factors. The Tobet laboratory has been examining the potential sex-dependence of cell migration ever since discovering a sex difference in immunoreactivity in radial glial fibers in the late 1980’s [41]. These efforts moved to live video microscopy in vitro in the early 1990’s [42] for cells visualized by dye binding [43] and then to cells visualized via transgenic fluorophores (green or yellow fluorescent proteins; [44]). Meanwhile, the effects of these processes could be realized in sex differences in cell positions in the developing hypothalamus. Such differences emerged in several laboratories [45–48]. Thus estradiol’s influences on cell movements in vitro may suggest that cell migration is one target for early molecular actions that impacts the development of brain regions controlling neuroendocrine functions.

Some sex differences in cell position may emerge following developmental disruptions. While investigating the positions of ERα containing neurons in and around the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) the Tobet laboratory discovered that disruption of GABAB receptor signaling affected cell positions only in females. This was true whether GABAB receptor signaling was lost due to receptor subunit knockout [39] or fetal exposure to a GABAB receptor antagonist [49].

While the neuron-centric view of brain development is expanding to embrace the role(s) of glia, interactions with brain vasculature may be equally important for understanding the final differentiation of functional capacity. In the course of studies of the developing PVN, it became clear that the vasculature was first and foremost several-fold denser inside the PVN than outside it. While this has been known for over 70 years [50], there are few studies of its development and none on its potential regulation. Using the GABAB receptor subunit knockout mouse noted above, it is clear that GABA signaling can alter PVN vascularization [51] and it is likely that several other factors can as well. In general, the vascular density appears to more often be greater in females, although there is significant variability.

The result of these studies is the capability to look at multiple tissues in vitro. While work started in ex vivo tissue slices looking at the preoptic area of embryonic rats [42] and then moved to mice [43], it also moved to other brain regions such as the ventromedial nucleus [52] and most recently to the PVN (Stratton and Tobet, unpublished). At the same time, visualizing live events in locations outside the brain became increasingly feasible starting with gonadotropin releasing hormone-containing neurons migrating from the olfactory system into the brain [53], to cellular movements in ex vivo slices from adult murine pituitaries [54] and prepubertal ovaries [55]. The range of tissues available for ex vivo examination is now providing a platform to examine key tissue interactions throughout life and across key target tissues such as the entire hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Increasing advances in biomedical engineering make the visualization of chemical signaling events in live tissue more accessible [54, 56, 57]. Putting these new devices to work in biological contexts promises to unlock aspects of cellular communications that drive tissues to organize in development, or function in adulthood.

Epigenetic programming in the developing brain

The concept that brief hormone exposure during the critical period for sexual differentiation of the brain results in life-long phenotypic changes has raised questions about how hormonal programming results in permanent neuroanatomical changes. Examination of the potential epigenetic factors regulating gene expression during neural organization is another novel approach to the study of sex differences which is gaining traction in this field [58]. Gonadal steroid hormones have been shown to alter DNA methylation and histone acetylation patterns in the developing brain and periphery, suggesting that perinatal hormone exposure may organize the neural substrate via epigenetic mechanisms, imparting long-term control over gene expression.

Epigenetic modification of chromatin involves changes to DNA bases and associated proteins in the absence of changes in the DNA sequence (for reviews see [59, 60]). Some of these epigenetic modifications include histone modifications and DNA methylation [61, 62], which are essential for events that occur during normal embryonic development, such as imprinting, X inactivation, and tissue-specific gene silencing. These same processes have also been the focus of research investigating how early life experiences and other external stimuli, such as maternal behavior, drug exposure, and learning impact an animal’s phenotype via altered gene expression [63–65]. Epigenetic modifications have been well documented in controlling neuronal gene expression [66, 67], and may therefore be important players underlying sex differences in and developmental control of gene expression, such as that of ERα.

DNA methylation is a modification conventionally associated with long-term decreases in gene expression. The first step in DNA methylation results in the enzymatic transfer of a methyl group to the 5′-position of the pyrimidine ring of a cytosine residue followed by a guanine (referred to as CpG dinucleotides). This modification of the cytosines in CpG dinucleotides is performed initially by the enzyme DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) and maintained by DNMT1 [60]. CpG sites are often found upstream or downstream of the transcriptional start site and methylation leads to the down regulation of transcription of the targeted genes by 1) recruiting methyl-binding proteins, which in turn recruit chromatin remodeling proteins, or 2) by blocking transcription start sites on a gene’s promoter [68]. The methylation status of DNA is dependent on the activity of DNMT enzymes as well as the corepressor/coactivtor complexes that bind to methylated cytosines. These protein complexes often contain histone modifying enzymes which directly unite methylated DNA to modified histones, such that inhibiting one epigenetic mark can alter the other [60, 69].

To investigate potential epigenetic mechanisms regulating the decline in ERα mRNA expression within the cortex across early postnatal development, the Wilson lab examined the methylation status of the ERα promoter during the first three weeks of life [28]. Genomic DNA was isolated from cortical tissue and the methylation status of ERα promoters was analyzed by methylation specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP) followed by pyrosequencing of the PCR product. The Wilson lab observed that several of the promoters of the mouse ERα gene become progressively methylated beginning at postnatal day 10. This age corresponds with the beginning of the decline in ERα mRNA expression in the cortex. Furthermore, chromatin precipitation assays determined that the methyl-DNA binding protein, MeCP2, is associated with the promoter at the same time it becomes methylated. These observations suggest that methylation may play a role in the suppression of ERα mRNA in the developing brain and that the ERα promoter is a target of MeCP2 activity. Matching the ERα mRNA expression pattern, no difference between males and females was observed in the cortex. Additionally the Wilson lab examined the expression of the de novo DNMT, DNMT3A, in the isocortex, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. A gradual increase with age was observed in DNMT3A mRNA expression and no sex difference was seen [70]. However, DNMT1 mRNA was significantly lower in the adult male prefrontal cortex and hippocampus suggesting potential sex differences in modulation of genes by methylation in the adult.

In addition to the Wilson lab, other groups have studied methylation patterns on the ERα promoter within areas organized by early estradiol exposure, namely the preoptic area (POA) and hypothalamus, since activation of ERα is known to be essential for masculinization of these regions [35]. Work from the McCarthy lab has shown that methylation of the ERα gene is altered by estradiol exposure during the critical period for sexual differentiation of the brain [71]. Importantly, and in light of the fact that the brain can undergo major changes across the lifespan in response to differing hormonal milieus [72–74], this group showed that methylation patterns established perinatally are dynamic across the animal’s lifespan. This finding adds further support to the argument that DNA methylation is not exclusively a permanent mark, but can come and go based on alterations in cellular signalling [75, 76].

Developmental programming by gonadal steroid hormones also appears to be involved in the establishment of sex differences in the expression of methyl binding proteins such as MeCP2 and co-repressor proteins, as well as alterations in histone modifications [1, 77, 78]. Histone proteins are the foundation of chromatin structure. DNA is wrapped around these proteins to form the basic building block of chromatin, the nulceosome [79]. The N-terminal tail of each histone protein extends from the nucleosome allowing for posttranslational modifications, which alter chromatin rigidity and transcriptional activity [80–82]. Post-translational modifications made to histones, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation, can increase or decrease gene expression depending on which specific amino acid residue on a given histone protein is modified [83]. Histone acetylation is a dynamic modification executed by histone acetyltransferase (HAT) enzymes and removed by histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes, which is generally associated with loosening of chromatin structure and enhancement of gene expression [84]. A recent study using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) found sex differences in acetylated histone H3 and H4 in ERα and aromatase promoter regions [85]. Interestingly, these sex differences were dependent on age. Males had higher levels of acetylated H4 at the ERα promoter on embryonic day 21, but lower levels by postnatal day 3 compared to females. H3 acetylation was higher on the aromatase 1f promoter in embryonic males, but lower in postnatal males compared to females. In addition, knockdown of HDAC 2 and 4 isoforms during the critical period for sexual differentiation of the brain resulted in impairment in male sexual behaviour in adulthood, implicating the importance of these enzymes in organization of the male brain [85].

The studies outlined above clearly implicate epigenetic processes in neonatal brain development. Although much more work is needed to interpret the role of these processes in hormonal programming, data from numerous labs have shown that many brain regions display sex and developmental differences in epigenetic processes. These data add to the growing body of evidence that epigenetics play a role in regulating neuronal gene expression. These processes are not specific to the developing brain, but appear important in the aging brain as well as other regions of the body.

Hormonal and sympathetic nervous system programming and activity in the ovary during development and aging

The mammalian ovary is not only under tight neuroendocrine control, but also under autonomic control exerted by neurons that innervate the different cellular components of the ovary, such as blood vessels, connective tissue, and follicles at different stages of development. Ovarian nerves are present from early development and are connected to follicles until ovulation, then continue their association with theca cells of the interstitial gland and are coupled to androgen biosynthesis [86]. Ovarian nerves present a high degree of plasticity. The ovary is rapidly reinnervated after transplantation and nerves increase both their number of fibers and activity around the time of puberty [87]. Although the bulk of the information known about the nervous control of the ovary has been obtained from animal models, the human ovary also presents a well developed network of sympathetic nerves around ovarian follicles and the activity of these nerves is physiologically coupled to a β-adrenergic mediated stimulation of progesterone and androgens secretion that increases at menopause [88, 89].

Importantly, evidence suggests that changes in ovarian sympathetic activity is involved in many sympathetic nerve activity-derived pathological states including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the most common ovarian pathology in women during their reproductive years [90]. Evidence for nerve activation during development of PCOS is supported by both human and animals studies [90–93]. Lara and his colleagues were among the first to demonstrate that hyperactivation of the sympathetic nerves arriving at the ovary participates in the development and maintenance of polycystic ovary (PCO) in the rat. This group found that PCO, induced by the administration of a single dose of estradiol valerate to rats, resulted in profound changes in ovarian catecholamine homeostasis, which were initiated before the development of cysts and persist after cysts are formed [94, 95]. The increased sympathetic nerve activity during development of PCO in rats is accompanied by a striking enhancement in ovarian steroidal responsiveness to both β-adrenoceptor and gonadotropin stimulation, and this abnormal response can be prevented by selectively ablating the neural input to endocrine cells of the ovary [94, 95]. The restoration of estrous cyclicity and ovulation resulting from ablation of the superior ovarian nerve implies a neural abnormality in the maintenance of PCO. The fact that a hormonal insult is able to activate sympathetic nerves and that this activation is causally related to a PCO pathological state reveals a new link through which the endocrine and nervous systems relate to the reproductive system: by altering nerve activity we can regulate endocrine function.

Neonatal programming in the neural control of the ovary by stress

Stress and neuroendocrine regulation interact to form a critical end point, which effects reproductive and other physiological processes via changes in body homeostasis. Studies have shown that a cold stress paradigm can specifically activate sympathetic nerves, without activating adrenal catecholamines or the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [96]. This stressor induces a hyperandrogenic state that is also related to the polycystic condition in the ovary [97, 98]. After 4 weeks of chronic cold stress the ovary develops a new class of antral follicles characterized by hyperthecosis, a condition similar to the one found in human PCOS [98]. However, if stress is prolonged for 8 weeks, both an hyperandrogenic condition and polycystic ovary morphology is clearly found [97]. Most importantly, both locus coeruleus lesions and superior ovarian nerve denervation reverse the hormonal and morphological changes. Lara and colleagues found that the origin of the sympathetic nerve pathway arriving at the ovary begins with thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) neurons located in the magnocellular region of the PVN [99]. In addition, glutamate appears to be the neurotransmitter involved in the initial activation of the neural pathway [100]. A functional relationship between the central and peripheral nerves was demonstrated following a decrease in the turnover rate of noradrenergic nerves arriving to the ovary when MK-801, a specific blocker of glutamate NMDA subtype receptors, was locally applied into the magnocellular region of the PVN [100]. These observations provide a different perspective from the well-known hypothalamic gonadotropin-control of ovary function and thus led to the prediction that a complementary neural pathway may control the ovary. In addition, it opened the possibility that changes in sympathetic nerve activity either physiological or pathological in origin, could participate in the origin, development, and maintenance of PCOS in humans. One piece of evidence supporting this possibility is the discovery that sympathetic nerves in the human ovary are physiologically coupled to β2-adrenergic receptors whose activation induces progesterone and androgen secretion from the ovarian follicle [88], and the close relation between higher stress levels and incidence of PCOS in patients [90, 92].

It is clear that hyperandrogenism is a fundamental characteristic in PCOS during adulthood. In addition, it is also clear that sympathetic nerve activity stimulates androgen secretion from the ovary, and that stress, as a chronic stimulus to overactivate sympathetic neurons, could be a triggering factor in the hyperandrogenism involved in the stress-induced polycystic ovary [97]. It is important to consider the critical windows in development during which hormonal or neurogenic stimuli, such as environmental disruptors, program long-lasting influences on neuroendocrine and reproductive function. When studying the rat ovary as a model, the timing in ovarian development must be considered to properly understand which steps of follicular development are subject to intervention. At birth there are no primordial follicles in the rat ovary, but the formation of primordial follicles starts soon after birth and is finished by postnatal day 4 (PN4). Thus, programming effects of hormones or nervous system activity after birth act on primordial follicles in transition to primary follicles. Just one session of a neonatal handling stress procedure, which affects both sympathetic nerve activity and glucocorticoid levels, has been shown to affect reproductive function in adulthood. This implies that emotional stress is able to permanently modify both endocrine and nerve control at the hypothalamic level [101, 102]. Although the handling procedure does not reproduce a natural environmental intervention, the wide range of long-lasting behavioral, neuroendocrine, and morphological changes induced by this procedure may indicate that biologically relevant pathways are activated by the repeated brief maternal separations combined with handling [103, 104]. In humans, non-human primates, and sheep this developmental period occurs during gestation and has been difficult to study because of challenges with the doses used to induce postnatal changes in follicular development and by the placental barrier controlling the amount of androgens of maternal origin reaching the fetus [105]. In this case, the placenta is a tissue that contains a high level of catecholamine transporters that help isolate the fetus from changes in maternal neurotransmitters. Thus it is possible that stress involving sympathetic nerves activity could affect development if it occurs during pregnancy as has been previously suggested [106, 107]. Cold stress during pregnancy results in large changes in the population of primordial follicles in female progeny, resembling a delayed development. This strongly suggests that sympathetic stress during development produces an increase in oocyte apoptosis. If this is correct chronic sympathetic activation during pregnancy could decrease the follicular pool. There may also be a specific sensitive window for sympathetic stress during ovary development that is located between the transition from oocyte nests to primordial follicles because neonatal β-adrenergic stimulation also produces a delay in primordial follicle development. Thus, sympathetic overactivation by stress during pregnancy could permanently modify reproductive function. In contrast, neonatal emotional stress (handling and separation from the mother) may have a more complicated effect, preferentially affecting central neuroendocrine systems through hypothalamic control of the gonadotropin secretion.

Involvement of sympathetic nerve activity and nerve growth factor during ovarian aging

Reproductive senescence in mammals is a poorly understood process that is critical to comprehend because of the increasing age of human populations. In addition, over the last decades women have postponed pregnancy until their 30s. The increase in the education of women has led to economic stability, social independence and a delayed maternity [108]. The decrease in the birth rate index with a concomitant delay in motherhood results in decreased fertility [109] and unsuccessful in vitro fertilization programs. Because of these problems, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of follicular development during the subfertility period and in ovarian aging. One of the factors regulating ovary function is sympathetic nerve activity and nerve growth factor (NGF), which acts as a neurotrophic factor. Paredes and colleagues have described that reproductive ageing is followed by a polycystic ovary condition associated with increased sympathetic nerve activity [110].

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is essential for the survival of peripheral sympathetic neurons. The ovary is a target tissue for the action of NGF and is dependent on the continuous supply of the peptide [111]. Blocking NGF action produces a decrease in the number of antral follicles. If innervation is present in the ovary during the perinatal period, and nerve activity increases upon reaching puberty, then coupling nerve activity to steroid secretion, either from the theca or granulosa cells of the ovary, could be of pathophysiological relevance not only in animals models but also for human being [86, 87, 112, 113].

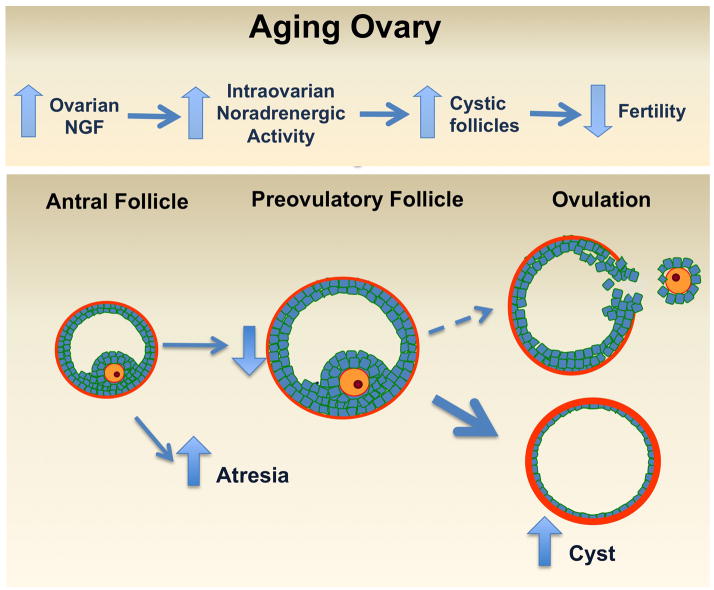

Although a decreased follicular pool represents the physiological aging of the ovary, an increased rate of follicular loss is a pathology that affects the follicular reserve pool and hence the optimal fertility period [114]. Reproductive ageing in women starts with shortened menstrual cycles and small increases in FSH and decreases in inhibin levels [115], which result in accelerated follicular growth and hence premature exhaustion of the follicular pool. Another factor involved in female infertility is PCOS, which is a condition that is maintained during ageing. Perimenopausal women present the syndrome with the same frequency as those of fertility age, however the ovary is not functioning at all [116]. It has been described that the ovaries of women with PCOS (18–44 years old) and postmenopausal (51-up years old) women have a higher density of nervous fibers as compared with age-matched control women [89]. The Paredes laboratory has demonstrated increased sympathetic nerve activity, which is causally related to a previous increase in NGF and its low affinity receptor p75 in a rodent model of PCOS [95, 117]. NGF locally delivered to the aging rat ovary to induce a neurotropin-dependent increase in ovarian sympathetic nerve activity provokes an ageing-like increase in the concentration of NE and the number of precystic follicles. In addition, NGF decreases the number of corpora lutea and the ovulation rate. These results suggest that the intra-ovarian excess of NGF accelerates follicular transition, probably by increasing sympathetic nerve activity (Paredes laboratory, data unpublished). These findings have a direct clinical application via the successful use of electro acupuncture procedures (designed to decrease intra-ovarian NGF levels) both in rats and patients with PCOS in recovering ovulatory cycles in women [118]. The high sympathetic innervation the ovary in PCOS and postmenopausal women suggest that they may develop through a similar mechanism and thus there may be a correlation between age-related infertility and over activation of the sympathetic nerve (Fig. 2). Animal models have shown that in addition to decreased fertility in older rats, there is a progressive increase in intraovrarian levels of NGF and in both ovarian NE concentration and nerve activity, which reach their highest levels when rats are completely infertile [110]. This is strongly correlated with a decreased number of preovulatory follicles and decreased ovulation, both of which parallel an increased rate of cyst formation by NGF-dependent mechanisms [119, 120]. Blocking the action of NE by exposing old rats to the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol recovered ovarian function (see paper in this issue). This suggests that β-adrenergic blockage produces an expansion of the window of subfertility and may promote successful fertility in ageing woman. We do not yet know the mechanisms underlying these findings, however we propose that changes in sympathetic nerve activity at the ovary regulate ovarian function at the end of reproductive period.

Figure 2.

We propose that the normal increase in ovarian sympathetic nerve activity that occurs with age, principally in the subfertility period, before cessation of the ovarian functions participates in the formation of cystic follicles, altering follicle development and inhibiting ovulation process. An increase of NGF or stress may cause accelerated ovarian aging.

Testosterone programming of metabolic and reproductive functions in males

As described above, exposure to excess gonadal steroid hormones during early fetal life is a known disruptor of several metabolic, neural, and reproductive parameters in females. Fetal exposure to excess androgens may occur in pregnant women with PCOS who show elevated levels of testosterone [121]. Under this hypothesis, the phenotype of this syndrome is perpetuated because the daughters of PCO mothers also exhibit metabolic and reproductive abnormalities like her mothers, including insulin resistance, high BMI, and high cholesterol [122–124]. Animal models have been used to assess the hypothesis that androgen excess during pregnancy in PCO women could be a factor of programming (or re-programming) affecting the metabolic homeostasis and reproductive function in PCO women [125–127]. In studies using sheep, monkeys and rats, many features exhibited by PCOS women are observed in immature and mature females, suggesting that excess androgens are the main factor intervening in the development of changes in the neuroendocrine control of ovarian function and in the deregulation of insulin-glucose homeostasis [128–131].

The impact of excess testosterone (T) during pregnancy in males born to PCOS mothers has been recently assessed. It is thought that excess T during fetal development may not have postnatal consequences for reproductive function, because T is released by the fetal gonad to participate in conjunction with other hormones in male sexual development. However, this assumption may not hold true considering observations made in men born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). In CAH syndrome, excess testosterone of fetal origin is produced during fetal development [132]. Studies have shown that men with CAH exhibit poor semen parameters [133] and that final height achieved is less than predicted based on that of parents [134]. In humans, Recabarren’s group has demonstrated that sons born to PCOS mothers have profound alterations in weight, lipid profile and insulin resistance as they age compared to sons born to control mothers [135]. Assessment of neuroendocrine and steroidogenic functions of the gonadal axis by a GnRH analogue test did not show differences in basal gonadotropin and steroid levels. There were also no differences following GnRH stimulation, during early infancy, childhood, or adulthood. However, testicular volume was lower in adult males born to PCOS mothers [136]. On the other hand, serum anti-Müllarian hormone levels were higher in infants and children born to PCOS mothers compared to boys of the same age born to control mothers.

Conversely, dramatic alterations in the gonadal axis have been demonstrated in an animal model, wherein male sheep exposed to excess T or DHT during a crucial stage of fetal development show significant reductions in sperm count, scrotum circumference, and sperm mobility [137, 138]. These abnormalities were accompanied by a high number of Sertoli cells, and a reduction in spermatogonia and spermatids. In addition, mRNA expression of FSH receptors was higher, while LH receptors mRNA expression was lower in T-males compared to control males [139]. LH pulsatility in T and DHT- exposed males at ages representing infancy, prepubertal and postpubertal stages of sexual development showed that DHT-exposed males exhibited higher levels of mean LH (ng/ml/6h) and higher amplitude pulses (ng/mL) compared to control males. LH levels and pulse amplitudes in T- exposed males were halfway between DHT- and control males. The frequency of LH pulses was not different between groups suggesting that pituitary gland sensitivity to endogenous GnRH pulses was higher in DHT- and T- exposed males than in control males [140]. This suggestion was evaluated using a GnRH analogue test which showed that LH secretion was higher in T- exposed males of 20 weeks of age compared to T- exposed males of 30 weeks of age. On the other hand, T response to LH was similar in both groups [141]. These results suggest a profound deregulation of the gonadal axis elicited by excess of androgens in males during fetal development.

Conclusions

The data presented during the Hormonal Programming in Development session at the US-South American Workshop in Neuroendocrinology reviewed above provides only a small overview of the vast actions of hormones during neural and gonadal organization and throughout life. The connecting theme between these presentations is that hormone exposure during various critical periods can have profound, lifelong consequences. These studies clearly show that hormonal exposure during critical periods in development is important for normal developmental processes, such as masculinization and defeminization of the brain. Hormonal organization of the brain has been shown to occur at numerous levels of analysis: from the genomic/epigenomic level, to differences in cell signaling factors, to alterations in cell morphology and migration, and finally qualitative differences in the structure and vasculature within brain nuclei. Concomitantly, excess hormone exposure and sympathetic nerve activity during critical developmental periods can have long-term negative consequences for gonadal development, resulting in deregulation of neurotransmitter and trophic factor signaling and PCOS phenotypes in females and reduced fertility in males.

Contributor Information

Bridget M Nugent, Email: Bnuge001@umaryland.edu, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 655 W. Baltimore Street, Room 5-014, Baltimore, MD, USA 21201, T: (410) 706-2654, F: (410) 706-8341.

Stuart A Tobet, Colorado State University 1617, Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, CO, 80523 USA.

Hernan E Lara, Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences., Universidad de Chile, PO Box 233, Santiago-1, Chile.

Aldo B Lucion, Departamento de Fisiologia Instituto de Ciências Básicas da Saúde (ICBS), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Sarmento Leite, 500, Porto Alegre, RS, CEP 90050-170, Brazil.

Melinda E Wilson, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, MS508 800 Rose St., Lexington, KY, USA 40536Her.

Sergio E Recabarren, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Universidad de Concepción, Av. Vicente Méndez 595, Casilla 537, Chillán, Chile.

Alfonso H Paredes, Laboratory of Neurobiochemistry. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular, Biology. Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences., Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, Sergio Livingstone 1007, Independencia, Santiago, Chile. 8380492.

References

- 1.Tsai HW, Grant PA, Rissman EF. Sex differences in histone modifications in the neonatal mouse brain. Epigenetics. 2009;4:47–53. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.1.7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhees RW, Shryne JE, Gorski RA. Onset of the hormone-sensitive perinatal period for sexual differentiation of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in female rats. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:781–786. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold AP, Gorski RA. Gonadal steroid induction of structural sex differences in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:413–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker J, De Mees C, Douhard Q, Balthazart J, Gabant P, Szpirer J, Szpirer C. Alpha-fetoprotein protects the developing female mouse brain from masculinization and defeminization by estrogens. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:220–226. doi: 10.1038/nn1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS, Lieberburg I, Chaptal C, Krey LC. Aromatization: important for sexual differentiation of the neonatal rat brain. Horm Behav. 1977;9:249–263. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy MM. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:91–134. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornton J, Zehr JL, Loose MD. Effects of prenatal androgens on rhesus monkeys: A model system to explore the organizational hypothesis in primates. Horm Behav. 2009;55:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonthuis P, Cox K, Searcy B, Kumar P, Tobet S, Rissman E. Of mice and rats: key species variations in the sexual differentiation of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:341–358. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A, Bornert JM, Argos P, Chambon P. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature. 1986;320:134–139. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koike S, Sakai M, Muramatsu M. Molecular cloning and charcterization of rat estrogen receptor cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2499–2513. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White R, Lees J, Needham M, Ham J, Parker M. Structural organization and expression of the mouse estrogen receptor. Molecular Endocrinology. 1987;1:735–744. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-10-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuiper G, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ERβ: Identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor–α and–β mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Österlund MK, Grandien K, Keller E, Hurd YL. The human brain has distinct regional expression patterns of estrogen receptor α mRNA isoforms derived from alternative promoters. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1390–1397. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Österlund MK, Gustafsson JÅ, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression within the human forebrain: distinct distribution pattern to ERα mRNA. J Clin Endo Metab. 2000;85:3840–3846. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González M, Cabrera-Socorro A, Pérez-García CG, Fraser JD, López FJ, Alonso R, Meyer G. Distribution patterns of estrogen receptor α and β in the human cortex and hippocampus during development and adulthood. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:790–802. doi: 10.1002/cne.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prewitt AK, Wilson ME. Changes in estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA in the mouse cortex during development. Brain Res. 2007;1134:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simerly R, Swanson L, Chang C, Muramatsu M. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miranda RC, Toran-Allerand CD. Developmental expression of estrogen receptor mRNA in the rat cerebral cortex: a nonisotopic in situ hybridization histochemistry study. Cerebral Cortex. 1992;2:1–15. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaff D, Keiner M. Atlas of estradiol-concentrating cells in the central nervous system of the female rat. J Comp Neurol. 1973;151:121–157. doi: 10.1002/cne.901510204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheridan PJ. Estrogen binding in the neonatal neocortex. Brain Res. 1979;178:201–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shughrue PJ, Stumpf WE, Maclusky NJ, Zielinski J, Hochberg RB. Developmental Changes in Estrogen Receptors in Mouse Cerebral Cortex between Birth and Postweaning: Studied by Autoradiography with llβ-Methoxy-16 α-[125I] Iodoestradiol. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1112–1124. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-2-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Keefe JA, Li Y, Burgess LH, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor mRNA alterations in the developing rat hippocampus. Mol Brain Res. 1995;30:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00284-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overman WH. Sex differences in early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood on cognitive tasks that rely on orbital prefrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:134–147. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galea LAM, Uban KA, Epp JR, Brummelte S, Barha CK, Wilson WL, Lieblich SE, Pawluski JL. Endocrine regulation of cognition and neuroplasticity: Our pursuit to unveil the complex interaction between hormones, the brain, and behaviour. Can J Exp Psychol. 2008;62:247–260. doi: 10.1037/a0014501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welborn BL, Papademetris X, Reis DL, Rajeevan N, Bloise SM, Gray JR. Variation in orbitofrontal cortex volume: relation to sex, emotion regulation and affect. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2009;4(4):328–39. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westberry JM, Trout AL, Wilson ME. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen receptor alpha gene expression in the mouse cortex during early postnatal development. Endocrinology. 2010;151:731–40. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurian JR, Bychowski ME, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger CJ, Auger AP. Mecp2 organizes juvenile social behavior in a sex-specific manner. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7137–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1345-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-α1b promoter and estrogen receptor-α expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emery DL, Royo NC, Fischer I, Saatman KE, McIntosh TK. Plasticity following injury to the adult central nervous system: is recapitulation of a developmental state worth promoting? J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1271–1292. doi: 10.1089/089771503322686085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubal DB, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Zhu H, Yu J, Cashion AB, Suzuki S, Gerhold LM, Bottner MB, Dubal SB. Differential modulation of estrogen receptors (ERs) in ischemic brain injury: a role for ERα in estradiol-mediated protection against delayed cell death. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3076–3084. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westberry JM, Prewitt AK, Wilson ME. Epigenetic regulation of the estrogen receptor alpha promoter in the cerebral cortex following ischemia in male and female rats. Neuroscience. 2008;152:982–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeFraja C, Conti L, Magrassi L, Govoni S, Cattaneo E. Members of the JAK/STAT proteins are expressed and regulated during development in the mammalian forebrain. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:320–330. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981101)54:3<320::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudwa A, Michopoulos V, Gatewood J, Rissman E. Roles of estrogen receptors α and β in differentiation of mouse sexual behavior. Neuroscience. 2006;138:921–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudwa AE, Bodo C, Gustafsson JÅ, Rissman E. A previously uncharacterized role for estrogen receptor β: Defeminization of male brain and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:4608–4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500752102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnold AP, Chen X. What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majdic G, Tobet S. Cooperation of sex chromosomal genes and endocrine influences for hypothalamic sexual differentiation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClellan KM, Stratton MS, Tobet SA. Roles for γ-aminobutyric acid in the development of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:2710–2728. doi: 10.1002/cne.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stratton MS, Searcy BT, Tobet SA. GABA regulates corticotropin releasing hormone levels in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in newborn mice. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobet S, Fox T. Sex-and hormone-dependent antigen immunoreactivity in developing rat hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:382–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tobet SA, Chickering TW, Hanna I, Crandall JE, Schwarting GA. Can gonadal steroids influence cell position in the developing brain? Horm Behav. 1994;28:320–327. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henderson RG, Brown AE, Tobet SA. Sex differences in cell migration in the preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus of mice. J Neurobiol. 1999;41:252–266. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19991105)41:2<252::aid-neu8>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knoll JG, Wolfe CA, Tobet SA. Estrogen modulates neuronal movements within the developing preoptic area–anterior hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1091–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scordalakes EM, Shetty SJ, Rissman EF. Roles of estrogen receptor α and androgen receptor in the regulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Comp Neurol. 2002;453:336–344. doi: 10.1002/cne.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orikasa C, Kondo Y, Hayashi S, McEwen BS, Sakuma Y. Sexually dimorphic expression of estrogen receptor β in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the rat preoptic area: implication in luteinizing hormone surge. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:3306–3311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfe CA, Van Doren M, Walker HJ, Seney ML, McClellan KM, Tobet SA. Sex differences in the location of immunochemically defined cell populations in the mouse preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus. Dev Brain Res. 2005;157(1):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Büdefeld T, Grgurevic N, Tobet SA, Majdic G. Sex differences in brain developing in the presence or absence of gonads. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:981–995. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stratton M, Budefeld T, Majdic G, Tobet S. Society for Neuroscience Abstract. Washington, DC: 2011. Embryonic GABA-B receptor blockade alters adult hypothalamic structure, and anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in mice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finley KH. The capillary bed of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1938;18:94–109. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frahm KA, Schow MJ, Okland TS, Eitel CM, Tobet SA. The vasculature within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in mice varies as a function of development, sub-nuclear location, and GABA signaling. Horm Metab Res. 2011 doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1304624. current issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dellovade TL, Davis AM, Ferguson C, Sieghart W, Homanics GE, Tobet SA. GABA influences the development of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Neurobiol. 2001;49:264–276. doi: 10.1002/neu.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tobet S, Hanna I, Schwarting G. Migration of neurons containing gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in slices from embryonic nasal compartment and forebrain. Dev Brain Res. 1996;97:287–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navratil AM, Knoll JG, Whitesell JD, Tobet SA, Clay CM. Neuroendocrine plasticity in the anterior pituitary: gonadotropin-releasing hormone-mediated movement in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1736–1744. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frahm KA, Clay CM, Tobet SA. Soc Study Reproduction Abstract. Milwaukee, WI: 2010. Characterization of an ovarian slice model in vitro to view ovulation. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pettine W, Jibson M, Chen T, Tobet S, Henry C. Characterization of Novel Microelectrode Geometries for Detection of Neurotransmitters. Sensors Journal, IEEE. 2011;(99):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lynn NS, Tobet S, Henry CS, Dandy DS. Mapping Spatio-Temporal Molecular Distributions Using a Microfluidic Array. Anal Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ac202314n. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy MM, Auger AP, Bale TL, De Vries GJ, Dunn GA, Forger NG, Murray EK, Nugent BM, Schwarz JM, Wilson ME. The Epigenetics of Sex Differences in the Brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12815–12823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3331-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolffe AP, Matzke MA. Epigenetics: regulation through repression. Science. 1999;286:481–786. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klose RJ, Bird AP. Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooper DN, Krawczak M. Cytosine methylation and the fate of CpG dinucleotides in vertebrate genomes. Hum Genet. 1989;83:181–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00286715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression--belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renthal W, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms in drug addiction. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller CA, Campbell SL, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation and histone acetylation work in concert to regulate memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Day JJ, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic mechanisms in cognition. Neuron. 2011;70:813–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo JU, Ma DK, Mo H, Ball MP, Jang MH, Bonaguidi MA, Balazer JA, Eaves HL, Xie B, Ford E. Neuronal activity modifies the DNA methylation landscape in the adult brain. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1345–1351. doi: 10.1038/nn.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tate PH, Bird AP. Effects of DNA methylation on DNA-binding proteins and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He F, Ge W, Martinowich K, Becker-Catania S, Coskun V, Zhu W, Wu H, Castro D, Guillemot F, Fan G. A positive autoregulatory loop of Jak-STAT signaling controls the onset of astrogliogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:616–625. doi: 10.1038/nn1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilson ME. Society for Neuroscience Abstract. Chicago, IL: 2009. Methylation of the ER promoter as a regulator of brain region specific hormone sensitivity. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwarz JM, Nugent BM, McCarthy MM. Developmental and hormone-induced epigenetic changes to estrogen and progesterone receptor genes in brain are dynamic across the life span. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4871–4881. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Konkle A, McCarthy MM. Developmental time course of estradiol, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone levels in discrete regions of male and female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2011;152:223–35. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmed EI, Zehr JL, Schulz KM, Lorenz BH, DonCarlos LL, Sisk CL. Pubertal hormones modulate the addition of new cells to sexually dimorphic brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:995–997. doi: 10.1038/nn.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2549–2554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Métivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Péron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, Ibberson D, Barath P, Demay F, Reid G. Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim MS, Kondo T, Takada I, Youn MY, Yamamoto Y, Takahashi S, Matsumoto T, Fujiyama S, Shirode Y, Yamaoka I. DNA demethylation in hormone-induced transcriptional derepression. Nature. 2009;461:1007–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature08456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurian JR, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger AP. Sex difference in mecp2 expression during a critical period of rat brain development. Epigenetics. 2007;2:173–178. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.3.4841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jessen HM, Kolodkin MH, Bychowski ME, Auger CJ, Auger AP. The nuclear receptor corepressor has organizational effects within the developing amygdala on juvenile social play and anxiety-like behavior. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1212–1220. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, review fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen JC, Tse C, Wolffes AP. Structure and Function of the Core Histone N-Termini: More Than Meets the Eye. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17637–17641. doi: 10.1021/bi982409v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wolffe AP, Hayes JJ. Chromatin disruption and modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:711–720. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ye J, Ai X, Eugeni EE, Zhang L, Carpenter LR, Jelinek MA, Freitas MA, Parthun MR. Histone H4 Lysine 91 Acetylation: A Core Domain Modification Associated with Chromatin Assembly. Mol Cell. 2005;18:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;40:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kuo MH, Allis CD. Roles of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases in gene regulation. Bioessays. 1998;20:615–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<615::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsuda KI, Mori H, Nugent BM, Pfaff DW, McCarthy MM, Kawata M. Histone Deacetylation during Brain Development Is Essential for Permanent Masculinization of Sexual Behavior. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2760–2767. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hernandez ER, Jimenez JL, Payne DW, et al. Adrenergic regulation of ovarian androgen biosynthesis is mediated via β2-adrenergic theca-interstitial cell recognition sites. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1592–1602. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ricu M, Paredes A, Greiner M, Ojeda SR, Lara HE. Functional development of the ovarian noradrenergic innervation. Endocrinology. 2008;149:50–56. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lara HE, Porcile A, Espinoza J, Romero C, Luza SM, Fuhrer J, Miranda C, Roblero L. Release of norepinephrine from human ovary. Endocrine. 2001;15:187–192. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:15:2:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heider U, Pedal I, Spanel-Borowski K. Increase in nerve fibers and loss of mast cells in polycystic and postmenopausal ovaries. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Greiner M, Paredes A, Araya V, Lara HE. Role of stress and sympathetic innervation in the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrine. 2005;28:319–324. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:3:319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lara H, Dorfman M, Venegas M, Luza S, Luna S, Mayerhofer A, Guimaraes M, Rosa e Silva A, Ramirez V. Changes in sympathetic nerve activity of the mammalian ovary during a normal estrous cycle and in polycystic ovary syndrome: studies on norepinephrine release. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:495–502. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jedel E, Waern M, Gustafson D, Landén M, Eriksson E, Holm G, Nilsson L, Lind AK, Janson PO, Stener-Victorin E. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Human Reproduction. 2010;25:450–456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stener-Victorin E, Ploj K, Larsson BM, Holmäng A. Rats with steroid-induced polycystic ovaries develop hypertension and increased sympathetic nervous system activity. Reprod Biol Endo. 2005;3:44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barria A, Leyton V, Ojeda S, Lara HE. Ovarian Steroidal Response to Gonadotropins and β-Adrenergic Stimulation Is Enhanced in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Role of Sympathetic Innervation. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2696–2703. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lara H, Ferruz J, Luza S, Bustamante D, Borges Y, Ojeda S. Activation of ovarian sympathetic nerves in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2690–2695. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.7902268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Adrenomedullary, adrenocortical, and sympathoneural responses to stressors: a meta-analysis. Endocr Regul. 2008;42:111–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bernuci MP, Szawka RE, Helena CVV, Leite CM, Lara HE, Anselmo-Franci JA. Locus coeruleus mediates cold stress-induced polycystic ovary in rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2907–2916. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dorfman M, Arancibia S, Fiedler J, Lara H. Chronic intermittent cold stress activates ovarian sympathetic nerves and modifies ovarian follicular development in the rat. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:2038–2043. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.008318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fiedler J, Jara P, Luza S, Dorfman M, Grouselle D, Rage F, Lara HE, Arancibia S. Cold Stress Induces Metabolic Activation of Thyrotrophin-Releasing Hormone-Synthesising Neurones in the Magnocellular Division of the Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus and Concomitantly Changes Ovarian Sympathetic Activity Parameters. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jara P, Rage F, Dorfman M, Grouselle D, Barra R, Arancibia S, Lara H. Cold-induced glutamate release in vivo from the magnocellular region of the paraventricular nucleus is involved in ovarian sympathetic activation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:979–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gomes CM, Donadio MVF, Anselmo-Franci J, Franci CR, Lucion AB, Sanvitto GL. Neonatal handling induces alteration in progesterone secretion after sexual behavior but not in angiotensin II receptor density in the medial amygdala: implications for reproductive success. Life Sci. 2006;78:2867–2871. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gomes C, Raineki C, de Paula PR, Severino G, Helena C, Anselmo-Franci J, Franci C, Sanvitto G, Lucion A. Neonatal handling and reproductive function in female rats. J Endocrinol. 2005;184:435–445. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Raineki C, De Souza M, Szawka R, Lutz M, De Vasconcellos L, Sanvitto G, Izquierdo I, Bevilaqua L, Cammarota M, Lucion A. Neonatal handling and the maternal odor preference in rat pups: involvement of monoamines and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein pathway in the olfactory bulb. Neuroscience. 2009;159:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Raineki C, Szawka RE, Gomes CM, Lucion MK, Barp J, Belló-Klein A, Franci CR, Anselmo-Franci JA, Sanvitto GL, Lucion AB. Effects of neonatal handling on central noradrenergic and nitric oxidergic systems and reproductive parameters in female rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:151–159. doi: 10.1159/000112230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Anderson H, Fogel N, Grebe SK, Singh RJ, Taylor RL, Dunaif A. Infants of women with polycystic ovary syndrome have lower cord blood androstenedione and estradiol levels. J Clin Endo Metab. 2010;95:2180–2186. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bzoskie L, Blount L, Kashiwai K, Humme J, Padbury J. The contribution of transporter-dependent uptake to fetal catecholamine clearance. Neonatology. 1997;71:102–110. doi: 10.1159/000244403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gu W, Jones CT. The effect of elevation of maternal plasma catecholamines on the fetus and placenta of the pregnant sheep. J Dev Physiol. 1986;8:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Broekmans FJ, Knauff EAH, te Velde ER, Macklon NS, Fauser BC. Female reproductive ageing: current knowledge and future trends. Trend Endo Metab. 2007;18:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Faddy M, Gosden R, Gougeon A, Richardson SJ, Nelson J. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Human Reproduction. 1992;7:1342–1346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Acu a E, Fornes R, Fernandois D, Garrido MP, Greiner M, Lara HE, Paredes AH. Increases in norepinephrine release and ovarian cyst formation during ageing in the rat. Reprod Biol Endo. 2009;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lara H, McDonald J, Ahmed C, Ojeda S. Guanethidine-mediated destruction of ovarian sympathetic nerves disrupts ovarian development and function in rats. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2199–2209. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-5-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ferruz J, Barria A, Galleguillos X, Lara H. Release of norepinephrine from the rat ovary: local modulation of gonadotropins. Biol Reprod. 1991;45:592–597. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aguado L, Petrovic S, Ojeda S. Ovarian β-adrenergic receptors during the onset of puberty: characterization, distribution, and coupling to steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1124–1132. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-4-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Menken J, Trussell J, Larsen U. Age and infertility. Science. 1986;233:1389–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.3755843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lenton EA, DeKretser DM, Woodward AJ, Robertson MD. Inhibin concentrations throughout the menstrual cycles of normal, infertile, and older women compared with those during spontaneous conception cycles. J Clin Endo Metab. 1991;73:1180–1190. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-6-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Margolin E, Zhornitzki T, Kopernik G, Kogan S, Schattner A, Knobler H. Polycystic ovary syndrome in post-menopausal women—marker of the metabolic syndrome. Maturitas. 2005;50:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dissen G, Parrott J, Skinner M, Hill D, Costa M, Ojeda S. Direct effects of nerve growth factor on thecal cells from antral ovarian follicles. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4736–4750. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bai YH, Lim SC, Song CH, Bae CS, Jin CS, Choi BC, Jang CH, Lee SH, Pak SC. Electro-acupuncture reverses nerve growth factor abundance in experimental polycystic ovaries in the rat. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;57:80–85. doi: 10.1159/000075382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lara H, Dissen G, Leyton V, Paredes A, Fuenzalida H, Fiedler J, Ojeda S. An increased intraovarian synthesis of nerve growth factor and its low affinity receptor is a principal component of steroid-induced polycystic ovary in the rat. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1059–1072. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.3.7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chávez-Genaro R, Lombide P, Domínguez R, Rosas P, Vázquez-Cuevas F. Sympathetic pharmacological denervation in ageing rats: effects on ovulatory response and follicular population. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2007;19:954–960. doi: 10.1071/rd07075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sir-Petermann T, Maliqueo M, Angel B, Lara H, Perez-Bravo F, Recabarren S. Maternal serum androgens in pregnant women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: possible implications in prenatal androgenization. Human Reproduction. 2002;17:2573–2579. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sir-Petermann T, Maliqueo M, Codner E, Echiburú B, Crisosto N, Pérez V, Pérez-Bravo F, Cassorla F. Early metabolic derangements in daughters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endo Metab. 2007;92:4637–4642. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sir-Petermann T, Codner E, Pérez V, Echiburú B, Maliqueo M, Ladrón de Guevara A, Preisler J, Crisosto N, Sánchez F, Cassorla F. Metabolic and reproductive features before and during puberty in daughters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endo Metab. 2009;94:1923–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sir-Petermann T, Márquez L, Cárcamo M, Hitschfeld C, Codner E, Maliqueo M, Echiburú B, Aranda P, Crisosto N, Cassorla F. Effects of birth weight on anti-Müllerian hormone serum concentrations in infant girls. J Clin Endo Metab. 2010;95:903–910. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Franks S. Do animal models of polycystic ovary syndrome help to understand its pathogenesis and management? Yes, but their limitations should be recognized. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3983–3985. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Padmanabhan V, Veiga-Lopez A, Abbott D, Recabarren S, Herkimer C. Developmental programming: impact of prenatal testosterone excess and postnatal weight gain on insulin sensitivity index and transfer of traits to offspring of overweight females. Endocrinology. 2010;151:595–605. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Padmanabhan V, Manikkam M, Recabarren S, Foster D. Prenatal testosterone excess programs reproductive and metabolic dysfunction in the female. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Roland AV, Nunemaker CS, Keller SR, Moenter SM. Prenatal androgen exposure programs metabolic dysfunction in female mice. J Endocrinol. 2010;207:213–223. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Abbott D, Barnett D, Bruns C, Dumesic D. Androgen excess fetal programming of female reproduction: a developmental aetiology for polycystic ovary syndrome? Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:357–374. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Abbott DH, Tarantal AF, Dumesic DA. Fetal, infant, adolescent and adult phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome in prenatally androgenized female rhesus monkeys. Am J Primatol. 2009;71:776–784. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dumesic DA, Abbott DH, Padmanabhan V. Polycystic ovary syndrome and its developmental origins. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2007;8:127–141. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9046-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.New MI. Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency (congenital adrenal hyperplasia) Am J Med. 1995;98:S2–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cabrera MS, Vogiatzi MG, New MI. Long term outcome in adult males with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endo Metab. 2001;86:3070–3078. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Reisch N, Flade L, Scherr M, Rottenkolber M, Pedrosa Gil F, Bidlingmaier M, Wolff H, Schwarz HP, Quinkler M, Beuschlein F. High prevalence of reduced fecundity in men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endo Metab. 2009;94:1665–1670. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Recabarren SE, Smith R, Rios R, Maliqueo M, Echiburú B, Codner E, Cassorla F, Rojas P, Sir-Petermann T. Metabolic profile in sons of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endo Metab. 2008;93:1820–1826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Recabarren SE, Sir-Petermann T, Rios R, Maliqueo M, Echiburú B, Smith R, Rojas-García P, Recabarren M, Rey RA. Pituitary and testicular function in sons of women with polycystic ovary syndrome from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endo Metab. 2008;93:3318–3324. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Recabarren SE, Rojas-García PP, Recabarren MP, Alfaro VH, Smith R, Padmanabhan V, Sir-Petermann T. Prenatal testosterone excess reduces sperm count and motility. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6444–6448. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rojas-García P, Recabarren MP, Palmer S, Tovar H, Gabler C, Einspanier R, Maliqueo M, Sir-Petermann T, Recabarren SE. Androgen Excess & PCO Society. Munich, Germany: 2010. Prenatal testosterone excess alters seminal and cellular characteristics in male sheep via its androgenic actions. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rojas-García PP, Recabarren MP, Sarabia L, Schön J, Gabler C, Einspanier R, Maliqueo M, Sir-Petermann T, Rey R, Recabarren SE. Prenatal testosterone excess alters Sertoli and germ cell number and testicular FSH receptor expression in rams. Am J Physiol Endo Metab. 2010;299:E998–E1005. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00032.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Recabarren SE, Recabarren MP, Rojas-García PP, Cordero M, Reyes JC, Sir-Petermann T. Prenatal exposure to androgens excess increases LH pulsatility during postnatal life in male sheep. Unpublished results. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1316291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Recabarren SE, Recabarren MP, Rojas-García PP, Arrate F, Einspanier R, Shon C, Gabler C, Sir-Petermann T. High pituitary responsiveness in young males exposed to exogenous testosterone excess during fetal development. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0006. Unpublished results. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]