Abstract

Behaviorally inhibited children display a temperamental profile characterized by social withdrawal and anxious behaviors. Previous research, focused largely on adolescents, suggests that attention biases to threat may sustain high levels of behavioral inhibition (BI) over time, helping link early temperament to social outcomes. However, no prior studies examine the association between attention bias and BI before adolescence. The current study examined the interrelations among BI, attention biases to threat, and social withdrawal already manifest in early childhood. Children (N=187, 83 Male, Mage=61.96 months) were characterized for BI in toddlerhood (24 & 36 months). At 5 years, they completed an attention bias task and concurrent social withdrawal was measured. As expected, BI in toddlerhood predicted high levels of social withdrawal in early childhood. However, this relation was moderated by attention bias. The BI-withdrawal association was only evident for children who displayed an attention bias toward threat. The data provide further support for models associating attention with socioemotional development and the later emergence of clinical anxiety.

Keywords: Temperament, Behavioral inhibition, Social withdrawal, Attention biases, Early childhood

Behavioral inhibition is a temperament trait characterized in infancy by signs of fear and wariness in response to unfamiliar (Schmidt et al. 1997) or novel (Marshall et al. 2009) sensory stimuli. The trait is also marked by vigilance, motor quieting, and withdrawal from social stimuli (Garcia Coll et al. 1984; Kagan et al. 1987). As they mature, behaviorally inhibited children experience more social rejection (Burgess et al. 2006; Wichmann et al. 2004), tend to avoid social stressors (Fox, Henderson et al. 2005; Pine 1999), and more often respond to rejection with attributions of internal failings and avoidant coping (Fox, Henderson et al. 2005). By adolescence, children with a pattern of high, stable behavioral inhibition are at increased risk for anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety (Biederman et al. 2001; Biederman et al. 1993; Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2009; Hirshfeld-Becker et al. 2007; Schwartz et al. 1999). Indeed, behavioral inhibition is one of the best characterized candidate endophenotypes for anxiety (Fox et al. 2007) as these children exhibit many of the known risk factors for anxiety at the behavioral (Degnan et al. 2008), cognitive (Wolfe and Bell 2007), and psychophysiological (McDermott et al. 2009; Reeb-Sutherland et al. 2009) level.

Yet, despite these vulnerabilities, only a minority of behaviorally inhibited children go on to exhibit clinical levels of anxiety (Degnan and Fox 2007). Thus, there is increasing interest in the moderating factors involved in the transition from risk to disorder in this subset of children. Previous work has shown that environmental factors such as family history of anxiety (Rosenbaum et al. 1992; Rosenbaum et al. 1988; Rosenbaum et al. 2000), parenting style (Burgess et al. 2001; Williams et al. 2009), or the use of childcare (Almas et al. 2011) moderate the outcome of early temperament (Degnan et al. 2010). The presence of a genetic risk marker, such as the short allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR), further influences outcome through interactions with the environment (Fox, Nichols et al. 2005). At the level of psychophysiology, increased event-related potentials (ERPs) to novelty (Reeb-Sutherland et al. 2009), high basal cortisol levels (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2008; Schmidt et al. 1997), and right frontal encephalogram (EEG) asymmetry (Fox et al. 2001; Henderson et al. 2001) each increase the likelihood that early temperamental biases are evident across childhood, thus increasing the risk for social withdrawal and anxiety (Fox and Reeb-Sutherland 2010).

Recently, there has been a great deal of interest in the role cognitive mechanisms may play in linking early behavioral inhibition to later social withdrawal and anxiety. This work builds on information processing models (Crick and Dodge 1994) to examine individual differences in social cognition, social processing, and coping in shy and withdrawn children (Burgess et al. 2006; Vasey and MacLeod 2001). In addition, parallel research has shown links between measures of information processing and research on therapeutics (Hakamata et al. 2010) and neurocognitive profiles (Pine et al. 2009). Of particular interest is work showing that attention mechanisms appearing early in the flow of information act as “gate-keepers,” influencing which aspects of the environment are selected for processing and thus shaping how the child experiences his or her social world. For example, Henderson (2010) found that shy children were particularly vulnerable to presenting a negative socioemotional profile, including negative attribution style, social anxiety, and poor self-perception of social avoidance, if they also had an elevated ERP (N2) response during a flanker task (Eriksen 1995).

Numerous studies have shown that anxious individuals, when presented with various combinations of threatening, positive, and neutral stimuli, spontaneously attend to threat (Bar-Haim et al. 2007; Logan and Goetsch 1993; Lonigan et al. 2004). For example, in the dot-probe task (Bradley et al. 1999; Mogg et al. 1997) individuals are presented with a threatening face or word paired with a neutral counterpart. By examining reaction times to targets subsequently presented at the location of either the threat or neutral stimuli, one can infer whether attention is drawn toward or away from the threat stimuli. Anxious individuals are reliably faster when the threat cue and target are in the same location versus when the target is paired with the neutral cue. These individuals may show avoidance when the neutral cue is presented with a positive word or face (Mogg, Philippot, and Bradley 2004), although some studies have found a bias for emotional stimuli in general, both positive and negative in affect (Bradley et al. 1999). ERP studies suggest that these patterns are associated with early automatic attention processes (Bar-Haim et al. 2005; Eldar et al. 2010; Pizzagalli et al. 1999).

Data directly paralleling the adult dot-probe literature in younger samples are now beginning to emerge. For example, Roy and colleagues (Roy et al. 2008) found that children and adolescents (ages 7 to 18 years) with generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder showed elevated attention biases to threat versus controls, regardless of the specific diagnosis. In a sample of 8- to 12-year olds with clinical anxiety, Waters and colleagues (Waters et al. 2010) found that the bias held only for the children with the most severe symptom scores. This pattern seems particularly strong in anxiety, relative to other pediatric mood disorders such as depression (Neshat-Doost et al. 2000).

In line with the behavioral (Rothbart et al. 1994; Rubin and Burgess 2001) and neural (McClure et al. 2007; Pérez-Edgar et al. 2007) parallels between anxiety and behavioral inhibition, children with this extreme temperament trait also display attention biases to threat stimuli (Pine et al. 2009). Of direct relevance to the current study, healthy adolescents with a childhood history of behavioral inhibition completed a dot-probe task (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2010). Mirroring clinically anxious children and adolescents (Roy et al. 2008; Waters et al. 2010), the previously inhibited adolescents, unlike adolescents without a history of behavioral inhibition, showed large attention biases to threat. More intriguingly, only those participants who displayed a large attention bias to threat showed a significant association between the magnitude of behavioral inhibition in childhood and persisting patterns of social withdrawal in adolescence. These data suggest that threat-related attention biases moderate the cognitive and behavioral processes that can lead to socioemotional maladaptation among behaviorally inhibited children.

There are a number of open questions that emerge from the threat bias—behavioral inhibition data. Perhaps most importantly, the most relevant prior study focused on adolescence, a period of heightened social anxiety (Beesdo et al. 2007). As such, these findings may predominantly reflect the influence of current functioning on attention, rather than antecedent developmental processes. As such, we do not know if the relations between attention, behavioral inhibition, and social behavior manifest before adolescence. If attention mechanisms act as early moderators of temperament, one might expect such associations to emerge in childhood, before one would expect to see many children manifesting clinical anxiety (Beesdo et al. 2007; Pine et al. 1998). That is, recent work suggests that less than 10% of preschoolers exhibit clinical levels of anxiety, with less than 5% specifically showing social phobia (Egger and Angold 2006).

The current study characterized levels of behavioral inhibition in the laboratory at 2 and 3 years of age. The children returned to the laboratory at 5 years of age and completed a dot-probe task. Analyses then examined potential relations between behavioral inhibition in the laboratory and subsequent attention biases 2 years later. We also looked to see if patterns of attention bias moderated the relation between early temperament and later levels of social withdrawal. A sustained pattern of social withdrawal places a child at increased risk for clinical anxiety (Caspi et al. 1988; Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2009; Hirshfeld et al. 1992; Kagan and Snidman 1999). Social withdrawal is therefore a developmentally appropriate marker of risk for very young children. As such, we relied on three independent sources of information: Laboratory observation of behavioral inhibition, child performance on the dot-probe task, and a composite measure of social withdrawal involving both parental report of temperamental shyness and laboratory observations of social behavior with an unfamiliar peer. To date, this is the youngest sample to be tested in this manner. We used these data to address a number of specific questions.

First, can 5-year-old children reliably complete a standard dot-probe task, patterned on the protocol normally used with adolescents and adults? Second, is early behavioral inhibition linked to attention bias patterns? If so, we predict that children with high levels of behavioral inhibition will show increased attention biases to threat. Third, will attention biases to threat moderate the relation between early behavioral inhibition and later socioemotional functioning? Again, based on the available literature, we predicted that a profile marked by early behavioral inhibition and an increased attention bias to threat would lead to heightened levels of social withdrawal.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=219, 99 male) were assessed at age 5 years (M=61.88 months, SD=3.56) as part of a larger longitudinal study of temperament and socioemotional development (Hane et al. 2008). Of these children, 134 (61.8%) were Caucasian, 30 (13.8%) were African American, 7 (3.2%) were Hispanic, 2 (1%) were Asian, and the remaining 30 (13.8%) children were of other or mixed ethnicity. An additional 14 children (6.5%) did not report ethnicity. The University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures and families consented to participate and were compensated for their participation.

Although the children were generally able to complete the dot-probe task, 32 participants (14.6%) were excluded from the final analyses due to poor performance (less than 60% accuracy). The remaining children had an average accuracy rate of 84.15% (SD=7.91). The participants excluded due to poor performance did not differ from the larger sample on age, gender, ethnicity, or behavioral inhibition, p’s>0.15. The final sample with dot-probe data included 187 participants (83 male, Mage=61.96 months, SD=3.47). See Tables 1 and 2 for mean scores and intercorrelations across the sample.

Table 1.

Relations between behavioral inhibition (BI) and the central measures of the study. BI was assessed at 24 and 36 months and then averaged into a single score. Attention biases and social withdrawal were both measured at 5 years. Mean scores are given for the full sample as well as for the BI groups created by median split of the composite score (standard deviations in parentheses). Significance markers represent statistical differences between the two BI groups in independent-sample t-tests

| Overall | Low BI | High BI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 83/104 | 35/51 | 42/48 |

| Age | 61.96 (3.47) |

61.81 (3.04) |

61.63 (3.37) |

| Behavioral Inhibition | 0.008 (0.398) |

−0.321** (0.189) |

0.321** (0.272) |

| Angry Bias | −6.31 (125.51) |

−11.91 (133.05) |

−3.56 (121.86) |

| Happy Bias | 3.50 (126.88) |

−9.80 (128.10) |

18.04 (127.29) |

| Social Withdrawal | 0.023 (0.740) |

−0.114** (0.636) |

0.187** (0.793) |

p<0.01; Gender = Male/Female; Age = Months

Table 2.

Relations between behavioral inhibition (BI) and the central measures of the study. BI was assessed at 24 and 36 months and then averaged into a single score. Attention biases and social withdrawal were both measured at 5 years. Intercorrelations among the central measures in the presented analyses. Degrees of freedom for the r-statistic are noted in parentheses

| Behavioral inhibition | Angry bias | Happy bias | Social withdrawal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Inhibition | 1.00 (176) |

|||

| Angry Bias | 0.020 (176) |

1.00 (187) |

||

| Happy Bias | 0.056 (176) |

0.012 (187) |

1.00 (187) |

|

| Social Withdrawal | 0.247** (174) |

−0.047 (185) |

0.017 (185) |

1.00 (185) |

p<0.01

Behavioral Inhibition Composite Score

Individual differences in early childhood temperament were assessed via a composite measure based on laboratory observations of behavior at 24 months and 36 months of age. Laboratory observations employed Kagan’s paradigm (Kagan and Snidman 1991) with an adapted coding system modeled on previous longitudinal studies (Fox et al. 2001). To create a stable measure of behavioral inhibition, scores from the two observation points were standardized and averaged for each child. Behavioral inhibition scores were available for 176 of the 187 children with viable dot-probe data. Higher scores reflected higher levels of inhibition (Full sample: M=−0.002, SD=0.40; Current sample: M= 0.008, SD=0.40). The children excluded due to missing behavioral inhibition scores did not differ from the larger cohort on the variables of interest, p’s>0.11.

Dot-Probe Task

The dot-probe task consisted of 8 practice and 80 experimental trials, presented in two 40-trial blocks. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four pseudo-random trial orders. Each trial began with the presentation of a 500-ms central fixation cross followed by the 500-ms presentation of a face pair. Immediately after the face pair disappeared, an asterisk probe appeared for 2,500 ms on either the left or right side of the screen in the location of one of the faces. Using a button box, the children were asked to indicate, as quickly and accurately as possible, which side of the screen the probe appeared. The inter-trial interval was 1,800 ms.

The children were seated 194 cm from a 13 in. CTX color monitor so that the stimuli were at 5.2° of visual angle. Presentation was controlled by the STIM stimulus presentation system from the James Long Company (Caroga Lake, NY). There were three types of face pairs presented: Angry/Neutral (32 trials), Happy/Neutral (32 trials), and Neutral/Neutral (16 trials). Expressions were portrayed by 30 different actors (50% male) taken from the NimStim face stimulus set (Tottenham et al. 2009). Trials were designated as congruent if the probe appeared in the same location as the emotion face (i.e., Angry or Happy) and incongruent if appearing in the location of the neutral face. Trial congruency, sex of the face, and probe location were counterbalanced across trials. Reaction times (RTs) and response accuracy were collected for each trial.

Social Withdrawal Composite Score

In order to construct a robust measure of social withdrawal at age 5 years, we applied a multi-method approach, integrating maternal report and laboratory observations of social behavior. When in a novel social environment socially withdrawn children often become quiet, show signs of emotional distress, and often refuse to engage in activity, even after a friendly social bid. The laboratory and maternal report measures were therefore chosen to reflect this profile, in line with the empirical literature and theory, particularly the work of Rubin and colleagues (Rubin and Burgess 2001; Rubin et al. 2009).

Parents completed the Colorado Child Temperament Inventory (CCTI; Buss and Plomin 1984). This 30-item measure asked mothers to rate their child with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all/Strongly disagree) to 5 (A lot/Strongly agree) on six factors pertaining to different dimensions of child temperament. These include emotionality, activity, attention, soothability, sociability, and shyness. The current analysis relied on scores from the shyness scale as it is a risk marker for anxiety (Caspi et al. 1988). Data on the reliability and validity of the CCTI can be found in Rowe and Plomin (1977). Shyness scores were available for 180 of the 187 children with viable dot-probe data (M=2.28, SD=0.85). The data from this sample displayed good psychometric reliability for shyness (Cron-bach’s alpha=0.83).

As part of the larger experimental battery, the children also took part in a play session with an unfamiliar peer (Degnan et al. 2011). The unfamiliar peer was recruited from the surrounding community and matched with the target child from the longitudinal cohort on age and sex. The two children were led into a playroom with several age-appropriate toys scattered about the floor. For the purpose of the current study, we focused on the target child’s behavior during an initial 10-minute freeplay session.

Coding proceeded in 2-minute epochs. Among the behavioral codes were unfocused/unoccupied behavior, activity level, negative affect, and positive affect. Ratings ranged from 1 (none observed in epoch) to 7 (observed throughout epoch). Inter-rater reliability (ICCs) ranged from 0.73 to 0.94 (M=0.82). Each code was averaged across epochs. To create the laboratory measure of behavior, the four codes (with positive affect and activity level reverse-scored) were standardized and averaged. This measure was then confirmed via factor analysis (Eigenvalue= 1.676, Mloading=0.60).

For the analyses below, social withdrawal was characterized as the mean of the laboratory score and the standardized CCTI shyness score (Mscore=0.024, SD=0.74).

Statistical Analyses

Trials with incorrect responses, RTs less than 200 ms, or RTs +/−2 SDs from the mean of all trials were removed before analyses began. As in previous dot-probe studies (Bradley et al. 1999; Mogg, Bradley et al. 2004), analyses focused on the relative bias patterns evident across the emotional (Angry or Happy) faces. Bias scores were calculated by subtracting the mean RT when the arrow replaced the emotion face (congruent trials) from the mean RT when the target replaced the neutral face (incongruent trials). Positive values indicate vigilance for the emotion stimuli and negative scores indicate avoidance of the emotion stimuli.

The overall sample means for dot-probe performance were in line with the published literature. Nevertheless, a good deal of variability in bias scores remained across the sample. This was most evident when children were subdivided into groups based on attention bias patterns (see Table 3). After careful review, we found that this was not due to outliers (e.g., all scores were within ±2.5 SDs from the mean). As a precaution, the RT responses to the happy and angry faces were log-transformed, bias scores were re-calculated, and the analyses noted here were run again. The findings did not differ from the analyses employing the non-transformed data. A parallel analysis was then run using the mean of harmonic means. Again, the results did not differ. For the sake of consistency with prior reports, results from the non-transformed data are presented below. Gender was initially included in the analytic plan. Analyses indicated that girls were more socially withdrawn than boys (0.187 vs. −0.153), t(172)=2.10, p<0.01. However, there were no additional gender-related findings, p’s>0.57, and outcomes did not differ when gender was used as a covariate. As such, this predictor was removed from subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Relations between behavioral inhibition (BI) and the central measures of the study. BI was assessed at 24 and 36 months and then averaged into a single score. Attention biases and social withdrawal were both measured at 5 years. Mean scores are given for the attention bias groups: threat vigilance, no bias, threat avoidance (standard deviations in parentheses)

| Threat vigilance | No bias | Threat avoidance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 28/28 | 20/39 | 30/29 |

| Age | 61.56 (3.21) |

61.77 (3.20) |

61.93 (3.22) |

| Behavioral Inhibition | −0.006 (0.362) |

0.022 (0.428) |

0.015 (0.407) |

| Angry Bias | 117.00** (74.20) |

−0.80** (25.96) |

−137.10** (80.70) |

| Happy Bias | 9.80 (129.1) |

13.30 (117.01) |

−9.10 (139.47) |

| Social Withdrawal | 0.052 (0.815) |

0.013 (0.634) |

0.008 (0.740) |

p<0.01; Gender = Male/Female; Age = Months

Children in the cohort did not complete a formal clinical interview. However, parents reported patterns of behavior problems for each participant using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000). Overall the sample was quite healthy as only seven children met T-score clinical cut-offs for the Anxiety/Depression, Withdrawal, and/or Internalizing scales (3.8% of the sample). To assess the potential effects of early anxiety, we removed these children from the analyses and examined the findings. Results were unchanged from the findings noted below. As such, the children remained in the reported analyses.

To parallel the developmental (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2010) and clinical (Roy et al. 2008) literature, a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA was first used to examine bias patterns as a function of behavioral inhibition group (Median split: Low vs. High) and face emotion (Angry vs. Happy). This allowed us to directly compare performance across the two face-emotion conditions. A categorical approach, however, can sometimes mask underlying relations. As such, simple correlations between the measures were also examined using continuous scores.

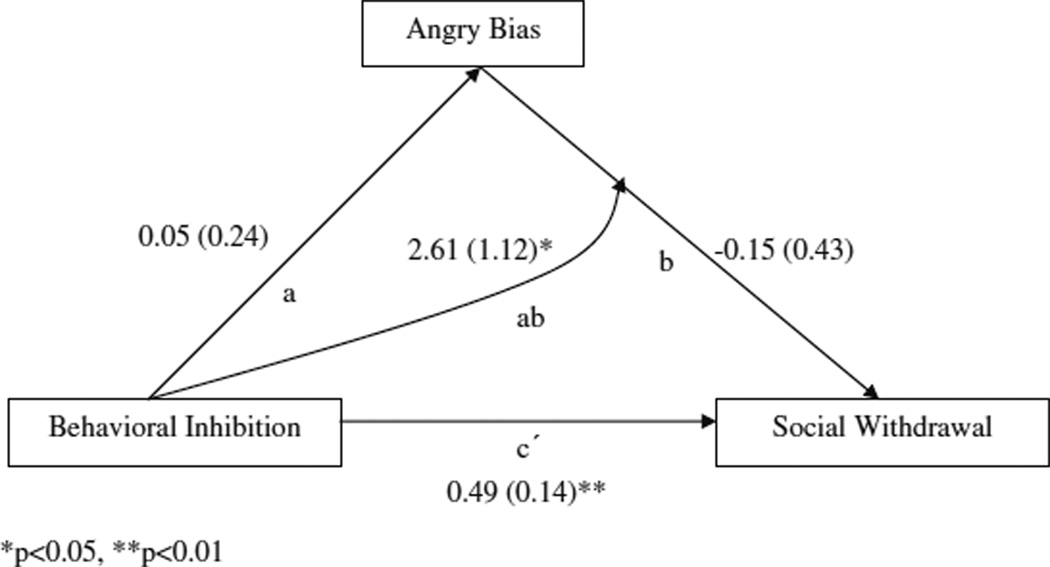

The potential relations among early temperament, attention biases, and social withdrawal at age 5 years were then evaluated. Specifically, we looked to see if the interrelations would best be characterized as a mediation or a moderation relation using a statistical model based on the work of Preacher et al. (2007). The standard approach (Baron and Kenny 1986) for testing mediation requires three linear models to estimate (1) the relation between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal (parameter c), (2) the relation between attention bias and social withdrawal (parameter b), (3) the relation between behavioral inhibition and attention bias (parameter a), and finally, (4) the residualized effect between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal (parameter c’). All paths must be significantly different from zero for mediation to be possible. Moderation is present when the relation between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal varies as a function of attention bias. This analysis provides the same information as a separate, stand-alone regression model. In the current analysis, one can simultaneously examine both the moderation and mediation relations. Given the constraints of the model, we ran the analysis separately for each of the faces (Angry and Happy). See Fig. 1 for a graphical presentation of the analyses for attention bias to angry faces.

Fig. 1.

Path results for the model examining how attention biases to threat may modify the relation between behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood and social withdrawal at age 5 years. Noted are the effect coefficients with standard errors in parentheses

Results

Relation between Behavioral Inhibition and Attention Biases to Emotion Faces

Means and standard deviations for the measures of interest are presented for the overall sample, as well as separately for the high and low behavioral inhibition groups, in Table 1. The initial repeated-measures ANOVA did not reveal significant main or interaction effects linking early behavioral inhibition to attention biases to emotion faces, p’s>0.19. Separate one-sample t-tests for bias scores were not significantly different from zero, p’s>0.18. Analyses with continuous behavioral inhibition scores (see Table 2) also failed to find significant links between early temperament and attention bias.

Relation between Behavioral Inhibition, Attention Biases, and Social Withdrawal

The results for both the angry face and happy face analyses are presented in Table 4. Figure 1 presents the results for the angry faces. For angry faces, the direct path between behavioral inhibition and attention bias levels was not significant, t=0.19, p=0.85, reflecting the ANOVA and correlations noted above. The mediated path was also nonsignificant, t=−0.35, p=0.73.

Table 4.

Predicting social withdrawal at age 5 years using measures of early temperament (behavioral inhibition composite at 24 and 36 months) and attention bias to emotional stimuli (angry and happy faces) at 5 years. The table presents the path coefficients (standard errors) and t-values for the separate moderated mediation models. BI—AB: Relation between BI and attention bias score; AB—SW: Relation between attention bias score and social withdrawal; BI—SW: Residualized effect of BI on social withdrawal; BI × AB—SW: The interaction of BI and attention bias on social withdrawal

| BI—AB |

AB—SW |

BI—SW |

BI × AB—SW |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a |

b |

c’ |

ab |

|||||

| ß (SE) | t | ß (SE) | t | ß (SE) | t | ß (SE) | t | |

| Angry Faces | 0.045 (0.242) | 0.19 | −0.147 (0.427) | −0.35 | 0.494 (0.135) | 3.66** | 2.608 (1.124) | 2.320* |

| Happy Faces | 0.191 (0.239) | 0.80 | −0.125 (0.430) | −0.33 | 0.473 (0.138) | 3.44** | −0.925 (1.147) | −0.807 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

As expected, however, behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood was strongly predictive of social withdrawal at age 5 years, as the effect was estimated at 0.50 with a standard error estimate of 0.14, t=3.66, p<0.001. The interaction between behavioral inhibition and attention bias was also significant. Here, the effect was estimated at 2.61 with a standard error estimate of 1.12, t=2.32, p=0.02. These findings indicate that there was no significant mediation relation among variables. Rather, the interaction indicates that attention bias to threat moderates the relation between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal, much as would be seen in a standard regression analysis.

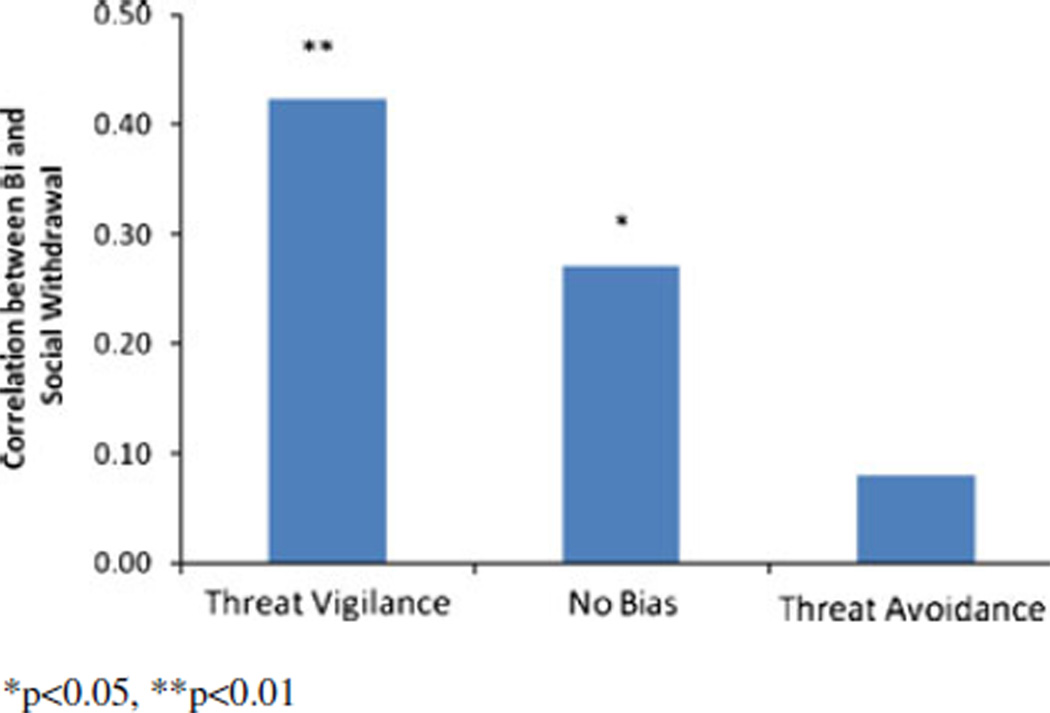

To interpret this interaction, the children were divided into three groups: children who avoided angry faces (i.e., a negative attention bias score, M=−137.1, SD=80.7), children with no attention bias (i.e., a score near zero, M=−0.80, SD=26.0), and children with a bias towards threat (i.e., a positive score, M=117.0, SD=74.2). Means and standard deviations across the measures of interest are noted separately for each bias group in Table 3.

The correlations between early behavioral inhibition and shyness in early childhood were then calculated separately for each group (Fig. 2). For children with a bias towards threat, there was a significant positive correlation between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal, r(59)=0.42, p=0.001. The relation was relatively weaker for children with no bias, r(59)=0.27, p=0.04, and absent for children who avoided threat, r(56)=0.08, p=0.56. Fisher’s Z-scores indicated that the correlations were significantly different between the vigilance and avoidance groups, Z=1.97, p= 0.05; the comparison between vigilance and no bias groups, Z=0.90, p=0.37, and between the no bias and avoidance groups, Z=1.08, p=0.28, were not significant.

Fig. 2.

Relation between BI in toddlerhood and social withdrawal at age 5 years as a function of attention patterns to threat. Children were grouped based on bias scores to angry faces: Vigilance, No Bias, and Avoidance

The equivalent model was examined for biases to happy faces. As presented above, there was a strong link between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal, t=2.78, p< 0.001. The remaining moderation and mediation paths were all non-significant (Table 4).

Discussion

A growing literature demonstrates that attention biases to threat are associated with patterns of socioemotional functioning, particularly in the case of anxiety (Bar-Haim et al. 2007; Pine et al. 2009). Questions remain, however, concerning the timing and emergence of this relation (Fox et al. 2007). The current study takes an important step in addressing this open empirical question by demonstrating a relation among temperament, attention bias to threat, and social outcomes in the first 5 years of life.

Indeed, the data suggest that attention biases, observed early in life on a standard laboratory reaction-time task, act in a strikingly similar manner as found previously among adolescents with a history of childhood behavioral inhibition (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2010). In that earlier study, childhood behavioral inhibition (assessed at four time points between 14 months and 7 years of age) predicted adolescent social difficulties at age 15 years. However, this association was only evident among individuals with a strong attention bias toward threat. In the current study, the link between early temperament and later social withdrawal was again stronger in children with a bias toward threat, relative to children with a bias away from threat.

Early vulnerabilities often begin to dissipate in the face of environmental (Degnan et al. 2010; Ghera et al. 2006) and maturational (Rueda et al. 2005) factors that ameliorate early signs of extreme reactivity (Fox et al. 2001). By illustrating the moderating role of attention, the current paper may help account for the minority of temperamentally extreme children who continue to exhibit stable, high levels of behavioral inhibition through childhood and go on to display elevated rates of anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2009) and anxious behaviors (Pérez-Edgar and Fox 2005), distinguishing this group from the majority of their peers who remain healthy despite equally extreme temperamental profiles early in life (Degnan and Fox 2007).

The current study attempted to document attention biases to threat in a very young sample. As such, the initial empirical question was quite straightforward: Can young children effectively complete a dot-probe paradigm using the same protocols and procedures employed with adolescents and adults? The initial answer is a qualified ‘yes’. Most children completed the task with little difficulty. However, almost 15% did not, with accuracy rates below 60%. This is a larger proportion than seen in the literature with older children (Eldar et al. 2008; Roy et al. 2008; Waters et al. 2010; Waters et al. 2008). As such, age 5 years appears to be at the cusp of when attention biases to threat can be reliably measured using the standard adult dot-probe task (Mogg, Bradley et al. 2004).

A recent study examined attention biases in young children (Mage=6 years) at risk for psychopathology due to maternal depression versus healthy controls (Kujawa et al. 2011). Consistent with the data presented here, 16% of their sample failed to meet a 60% accuracy cut-off. This study also points to the fact that straightforward links between risk and attention biases may be hard to find in young children. In particular, the authors preceded the dot-probe task with a negative mood induction to prime biases and found significant vigilance in only one group: at-risk girls. This was despite relatively long exposure to the affective faces (1,500 ms vs. the standard 500 ms).

As with many newly emerging behaviors, the children in the current study also displayed a great deal of variability in their performance. Although average bias scores were comparable to published studies, the range of scores was quite large. There is also the possibility that, had we been able to assess attention biases and behavioral inhibition concurrently, a significant relation would have been evident. This would suggest that intervening mechanisms, such as parenting or evolving self-regulatory skills, moderate the relation between temperament and attention from the earliest years. Repeated testing in young children over time should help resolve this question.

A third alternate explanation would posit that the measures employed were unstable due to the fact that (a) children only completed 80 total experimental trials (older children often complete considerably more trials) and (b) behavioral inhibition was characterized using only two time points. However, given the striking similarity between the current findings and the adolescent data from the older longitudinal cohort, these explanations appear unlikely.

Indeed, the moderation findings closely parallel previous adolescent data (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2010), where a significant attention bias by behavioral inhibition interaction (t=2.33) also emerged. In the adolescent study, as in the current study, the correlation between early behavioral inhibition and adolescent social withdrawal diminished across sub-groups of adolescents with large threat bias (r= 0.48), small threat bias (r=0.12), and threat avoidance (r= −0.08). However, unlike in the current study, there was no significant correlation between early behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal in the overall sample, presumably due to the long interval between temperament and withdrawal assessments. This would afford more time for maturational and environmental moderation.

The young children in the current sample showed a strong correlation between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal, again perhaps reflecting the shorter time lapse between the two testing points. Yet, the moderation relation was still evident (t=2.32) with correlations again diminishing across the large bias (r=0.42), no bias (r=0.27), and avoidance (r=0.08) groups. Neither sample exhibited significant findings when examining biases to happy faces.

These cognitive and behavioral relations suggest that the link between temperament, attention bias, and social functioning is early appearing and may be fairly stable over time. As noted above, attention bias and social withdrawal were assessed concurrently. Therefore, one cannot determine with certainty the directionality of the observed effects, such that it may be that social withdrawal is moderating the relation between behavioral inhibition and attention bias. Future longitudinal studies assessing these factors at each time point will be needed to address this question.

These interrelations may be supported by a broader biological network associated with both temperament and anxiety. For example, attention bias patterns to both positive and negative stimuli are moderated by serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) allelic status (Beevers et al. 2007; Fox et al. 2009; Gibb et al. 2009; Pérez-Edgar et al. 2010). 5-HTTLPR status, in turn, has been linked to trajectories of behavioral inhibition (Fox, Nichols et al. 2005) and increased anxiety (Lesch et al. 1996). In much the same manner, right frontal EEG asymmetry has been linked to increased levels of behavioral inhibition (Henderson et al. 2001; Schmidt et al. 1999) and anxiety (Davidson 2002). Newly emerging work demonstrates that EEG asymmetry is linked to attention bias patterns as well (Miskovic and Schmidt 2010; Schutter et al. 2001). Miskovic and Schmidt (2010) also found a similar pattern linking attention biases to threat to depressed vagal tone levels.

Finally, hyperactivity in the amygdala has been strongly implicated in both anxiety (Pine 2007) and behavioral inhibition (Pérez-Edgar et al. 2007; Schwartz et al. 2003). In two fMRI studies, Monk and colleagues found that clinically anxious adolescents show perturbations in the amygdala (Monk et al. 2008) and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Monk et al. 2006) response to threat during the dot-probe task, varying with the length of exposure to the stimuli. Parallel work is needed with healthy behaviorally inhibited individuals to see if this relation holds for children at risk for anxiety.

There are several outstanding questions concerning this phenomenon that arise from the current study’s limitations. First, attention biases were measured concurrently with social withdrawal. As such, we have yet to see if attention bias patterns can prospectively predict patterns of socio-emotional development. Longitudinal studies with repeated assessments of attention will also allow us to observe any developmental changes in bias patterns over time, as noted above. Such a study will also be able to address the possibility that avoidance of threat may be protective for anxiety, as hinted by the current data. This is, to date, an untested question in the literature.

Second, almost 15% of the children were unable to perform the task at the level of proficiency needed for analysis. This leaves open the possibility that there are relevant developmental differences between children who can or cannot complete the task. Third, this also calls into question the stability of bias patterns in young children (Pérez-Edgar and Bar-Haim 2010). Test-retest studies are therefore necessary in order to understand the strength of evident bias patterns.

The current study adds to our understanding of the role early attention biases to threat may play in socioemotional development. The data suggest that the relation between temperament, attention biases, and socioemotional trajectories is early emerging, relatively stable, and part of a larger neurocognitive network. As such, this appears to reflect a normative process that is evident before the up-tick in anxiety often seen in adolescence (Beesdo et al. 2007). Indeed, even after removing children with elevated levels of reported behavior problems, the overall pattern of findings remained significant. To speculate, these forces may work in tandem with increases or decreases in individual risk for maladjustment or disorder. In the current study, early behavioral inhibition predicted later levels of social withdrawal only in children who displayed a large bias towards threat. Future work, in both children and adults, will be able to examine the specificity and stability of the current findings across time and context (Ollendick and Hirshfeld-Becker 2002).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the many individuals who contributed to the longitudinal data collection and behavioral coding. We would also like to thank Drs. Karin Mogg and Brendan P. Bradley for advising on the design and implementation of the dot-probe task. Finally, we would especially like to thank the parents of the children who participated and continue to participate in our studies. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HD# 17899) to Nathan A. Fox. Support for manuscript preparation was also provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to Koraly Pérez-Edgar (MH# 073569).

Contributor Information

Koraly Pérez-Edgar, Department of Psychology, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA, kperezed@gmu.edu.

Bethany C. Reeb-Sutherland, Department of Human Development, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Jennifer Martin McDermott, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA.

Lauren K. White, Department of Human Development, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Heather A. Henderson, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33124, USA

Kathryn A. Degnan, Department of Human Development, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Amie A. Hane, Department of Psychology, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA

Daniel S. Pine, Section on Development and Affective Neuroscience, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD 20895, USA

Nathan A. Fox, Department of Human Development, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Almas AN, Phillips DA, Henderson HA, Hane AA, Degnan KA, Moas OL, et al. The relations between infant negative reactivity, non-maternal childcare, and children’s interactions with familiar and unfamiliar peers. Social Development. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Glickman S. Attentional bias in anxiety: A behavioral and ERP study. Brain and Cognition. 2005;59:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg M, van IJzendoorn M. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, Stein M, Hofler M, Lieb R, et al. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Gibb B, McGeary JE, Miller IW. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and biased attention for emotional word stimuli among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:208–212. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, et al. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:814–821. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley BP, Mogg K, White J, Groom C, de Bono J. Attentional bias for emotional faces in generalized anxiety disorder. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:267–278. doi: 10.1348/014466599162845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Rubin KH, Cheah CSL, Nelson LJ. Behavioral inhibition, social withdrawal, and parenting. In: Crozier WR, Alden LE, editors. International handbook of social anxiety: Concepts, research and interventions relating to the self and shyness. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Wojslawowicz J, Rubin K, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C. Social information processing and coping strategies of shy/withdrawn and aggressive children: Does friendship matter? Child Development. 2006;77:371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ, Elder G., J Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:824–831. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan K, Pine D, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson H, Diaz Y, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition during infancy and early childhood predicts the development of anxiety disorders in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Dodge K. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Anxiety and affective style: Role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: The moderating roles of child care history, maternal personality, and maternal behavior. Social Development. 2008;17:471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Almas AN, Fox NA. Temperament and the environment in the etiology of childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:497–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Hane AA, Henderson HA, Moas OL, Reeb-Sutherland BC, Fox NA. Longitudinal stability of temperamental exuberance and social-emotional outcomes in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0021316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar S, Ricon T, Bar-Haim Y. Plasticity in attention: Implications for stress response in children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar S, Yankelevitch R, Lamy D, Bar-Haim Y. Enhanced neural reactivity and selective attention to threat in anxiety. Biological Psychology. 2010;85:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen C. The flankers task and response competition: A useful tool for investigating a variety of cognitive problems. In: Bundesen C, Shibuya H, editors. Visual selective attention. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1995. pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Reeb-Sutherland BC. Biological moderators of infant temperament and social withdrawal. In: Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, editors. The development of shyness and social withdrawal. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Nichols KE, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Schmidt LA, Hamer DH, et al. Evidence for a gene environment interaction in predicting behavioral inhibition in middle childhood. Psychological Science. 2005;16:921–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Hane AA, Pine DS. Plasticity for affective neurocircuitry: How the environment affects gene expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fox E, Ridgewell A, Ashwin C. Looking on the bright side: Biased attention and the human serotonin transporter gene. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences. 2009;276:1747–1751. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Kagan J, Reznick JS. Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development. 1984;55:1005–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Ghera MM, Hane AA, Malesa EE, Fox NA. The role of infant soothability in the relation between infant negativity and maternal sensitivity. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Benas JS, Grassia M, McGeary J. Children’s attentional biases and 5-HTTLPR genotype: Potential mechanisms linking mother and child depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:415–426. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, et al. Attention bias modification treatment: A meta-analysis towards the establishment of novel treatment for anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ. Behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1491–1496. doi: 10.1037/a0012855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA. Electrophysiological correlates of cognitive control and the regulation of shyness in children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:177–193. doi: 10.1080/87565640903526538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Temperamental contributions to social behavior: The moderating roles of frontal EEG asymmetry and gender. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:68–74. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Faraone SV, Snidman N, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:103–111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, et al. Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychological Science. 1991;2:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Early childhood predictors of adult anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:1536–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa AJ, Torpey D, Kim J, Hajcak G, Rose S, Gotlib IH, et al. Attentional biases for emotional faces in young children of mothers with chronic or recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heilis A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan AC, Goetsch VL. Attention to external threat cues in anxiety states. Clinical Psychology Review. 1993;13:541–559. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Vasey MW, Phillips BM, Hazen RA. Temperament, anxiety, and the processing of threat-relevant stimuli. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:8–20. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Reeb BC, Fox NA. Electrophysiological responses to auditory novelty in temperamentally different 9-month-old infants. Developmental Science. 2009;12:568–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair RJR, et al. Abnormal attention modulation of fear circuit function in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott JM, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox N. A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskovic V, Schmidt L. Frontal brain electrical asymmetry and cardiac vagal tone predict biased attention to social threat. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2010;75:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP, De Bono J, Painter M. Time course of attentional bias for threat information in non-clinical anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP, Miles F, Dixon R. Time course of attentional bias for threat scenes: Testing the vigilance-avoidance hypothesis. Cognition and Emotion. 2004;18:689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Philippot P, Bradley BP. Selective attention to angry faces in clinical social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:160–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Leibenluft E, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attention bias in responsive to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1091–1097. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Mai X, Louro HMC, et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neshat-Doost HT, Moradi AR, Taghavi MR, Yule W, Dalgleish T. Lack of attentional bias for emotional information in clinically depressed children and adolescents on the dot probe task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:363–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Hirshfeld-Becker DR. The developmental psychopathology of social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:44–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y. Application of cognitive-neuroscience techniques to the study of anxiety-related processing biases in children. In: Hadwin J, Field A, editors. Information processing biases in child and adolescent anxiety. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:681–706. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Roberson-Nay R, Hardin MG, Poeth K, Guyer AE, Nelson EE, et al. Attention alters neural responses to evocative faces in behaviorally inhibited adolescents. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Schmidt LA, Henderson HA, Schulkin J, Fox NA. Salivary cortisol levels and infant temperament shape developmental trajectories in boys at risk for behavioral maladjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:916–925. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion. 2010;10:349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Gorodetsky E, Hodgkinson CA, Goldman D, et al. Variations in the serotonin transporter gene are linked to heightened attention bias to threat. Biological Psychology. 2010;83:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS. Pathophysiology of childhood anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:1556–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS. Research review: A neuroscience framework for pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:631–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Helfinstein SM, Bar-Haim Y, Nelson E, Fox NA. Challenges in developing novel treatments for childhood disorders: Lessons from research on anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:213–228. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli D, Regard M, Lehmann D. Rapid emotional face processing in the human right and left brain hemispheres: An ERP study. NeuroReport. 1999;10:2691–2698. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199909090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb-Sutherland BC, Vanderwert RE, Degnan KA, Marshall PJ, Pérez-Edgar K, Chronis-Tuscano A, et al. Attention to novelty in behaviorally inhibited adolescents moderates risk for anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1365–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Gersten M, Hirshfeld DR, Meminger SR, Herman JB, et al. Behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia: A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:463–470. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290083010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc E, Hirshfeld D, Faraone S, Kagan J. Comorbidity of parental anxiety disorders as risk for childhood-onset anxiety in inhibited children. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:475–481. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Friedman D, et al. A controlled study of behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:2002–2010. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL. Temperament and social behavior in childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Plomin R. Temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1977;41:150–156. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Sweeney M, et al. Attention bias toward threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1189–1196. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825ace. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB. Social withdrawal and anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, Posner MI, Rothbart MK. The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:573–594. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Fox NA, Rubin KH, Sternberg EM, Gold PW, Smith CC, et al. Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses in shy children. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;30:127–140. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199703)30:2<127::aid-dev4>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Fox NA, Schulkin J, Gold PW. Behavioral and psychophysiological correlates of self-presentation in temperamentally shy children. Developmental Psychobiology. 1999;35:119–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutter DJL, Putman P, Hermans E, van Honk J. Parietal electroencephalogram beta asymmetry and selective attention to angry facial expressions in healthy human subjects. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;314:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Wright CI, Shin LM, Kagan J, Rauch SL. Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: Adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science. 2003;300:1952–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.1083703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka J, Leon A, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare T, et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasey MW, MacLeod C. Information-processing factors in childhood anxiety: A review and developmental perspective. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in children with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:435–442. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181642992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Henry J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias towards angry faces in childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2010;41:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann C, Coplan R, Daniels T. The social cognitions of socially withdrawn children. Social Development. 2004;13:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Degnan KA, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Pine DS, et al. Impact of behavioral inhibition and parenting style on internalizing and externalizing problems from early childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:1063–1075. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe C, Bell M. The integration of cognition and emotion during infancy and early childhood: Regulatory processes associated with the development of working memory. Brain and Cognition. 2007;65:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]