Abstract

The Tmem16 gene family was first identified by bioinformatic analysis in 2004. In 2008, it was shown independently by 3 laboratories that the first two members (Tmem16A and Tmem16B) of this 10-gene family are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. Because these proteins are thought to have 8 transmembrane domains and be anion-selective channels, the alternative name, Anoctamin (anion and octa=8), has been proposed. However, it remains unclear whether all members of this family are, in fact, anion channels or have the same 8-transmembrane domain topology. Since 2008, there have been nearly 100 papers published on this gene family. The excitement about Tmem16 proteins has been enhanced by the finding that Ano1 has been linked to cancer, mutations in Ano5 are linked to several forms of muscular dystrophy (LGMDL2 and MMD-3), mutations in Ano10 are linked to autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia, and mutations in Ano6 are linked to Scott syndrome, a rare bleeding disorder. Here we review some of the recent developments in understanding the physiology and structure-function of the Tmem16 gene family.

Keywords: chloride channels, patch clamp, ion channels, channelopathies, ion transport, muscular dystrophy, ataxia, blood clotting

Introduction

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs) play manifold roles in cell physiology1, 2 including epithelial secretion3, 4, sensory transduction and adaptation5, 6, 7, 8, regulation of smooth muscle contraction9, control of neuronal and cardiac excitability10, and nociception11. CaCCs were first described in Xenopus oocytes12, 13 and salamander rods14 in the early 1980's, but it was not until 3 years ago that the proteins responsible for these channels were identified. Prior to that, several other proteins were proposed as molecular candidates. These include ClC-315, CLCAs16, and bestrophins17. None of these proteins have properties that exactly fit those of classical CaCCs1. Although bestrophins are indeed CaCCs, their expression profile is more restricted and their biophysical properties are different from classical CaCCs17. So, in 2008, the announcements that three labs had cloned genes that encoded classical CaCCs generated considerable excitement18, 19, 20. The two genes that have been shown definitively to encode CaCCs are called Tmem16A and Tmem16B. These are two members of a family that consists of 10 genes in mammals21. Yang et al19 proposed the new name “anoctamin” or Ano (anion+octa=8) and this name is now the official HUGO nomenclature and has replaced Tmem16 in Genbank. Tmem16A is now Ano1, Tmem16B is Ano2, and so-on except that the letter I is skipped in the Tmem16 nomenclature so that Tmem16J is Ano 9 and Tmem16K is Ano10. There is some dissatisfaction in the field with the Ano nomenclature because, as discussed below, it is not certain that all the members of this family are anion channels or have the 8-transmembrane topology. Also, the term “Ano” has a potentially objectionable meaning in the Spanish language22. For this reason, the Tmem16 terminology still remains in use in parallel with Ano. This review summarizes some of the recent developments in this field. The reader should consult several other outstanding reviews on Tmem16/Ano proteins for more detail and different perspectives22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29.

Structure-function of anoctamins

Hydropathy analysis shows that all anoctamins have eight hydrophobic helices that are likely to be transmembrane domains with cytosolic N- and C-termini. This predicted topology has been confirmed experimentally for Ano7, whose topology has been determined using inserted HA epitope tag accessibility and endogenous N-glycosylation30. Although this topology is appealing, the epitope tag accessibility methodology used to identify intracellular domains of Ano7 does not clearly distinguish between intracellular domains and protein that is not efficiently trafficked to the plasma membrane. Because of this technical limitation and the fact that the topology of other Anos has not been experimentally determined, more investigation is required to establish the topology of these proteins.

The quaternary structure of Ano1 was recently determined to be that of a homodimer using both migration in native gels as well as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)31, 32. Ano1 subunits associate before they are trafficked to the plasma membrane. The association of Ano1 subunits is likely due to noncovalent interactions, as the Ano1 assembly cannot be separated into monomers by chemical reduction with DTT. The oligomeric state is not affected by changes in intracellular Ca2+, suggesting that the homodimeric structure of Ano1 is not a determinant of channel gating. The homodimeric structure of Ano1 is reminiscent of that of CLC chloride channels, although it is not known whether the channel functions as a dimer or a higher order oligomer that is not detected quantitatively by the techniques used to date. For example, it is possible that the dimer is a biochemically stable form, but that dimerization of the dimers is required to create a functional channel. Further, it is not known whether Ano1 can form heteromers with other Anos or whether it associates with other accessory subunits. It will be interesting to see if Ano1 subunits assemble to form a single functional pore, or if each subunit contains a separate Cl− conduction pathway, similar to the double barrel structure of CLC channels.

Multiple isoforms

At least 4 splice variants have been identified for Ano133 and two splice variants have been found for Ano734. Human Ano1 has 4 different alternatively-spliced segments, a, b, c, and d corresponding, respectively, to an alternative initiation site, exon-6b, exon-13, and exon-1533. Segments a and b are located in the N-terminus and c and d are in the first intracellular loop. The variant with all 4 segments is designated as Ano1abcd; the variant lacking segments b and d, for example, is Ano1ac. Analysis of ESTs in Genbank predicts that several of the other Anos also have multiple splice variants. Some of these variants may not have channel functions because they are predicted to lack some or all of the transmembrane domains. For example, the short form of Ano7, which has been shown to be translationally expressed, is a short, soluble protein34. The four splice variants of Ano1 exhibit different voltage-dependent and Ca2+-dependent gating properties33, 35. Thus, alternative splicing is likely to contribute to the heterogeneity of CaCC currents observed in native tissues.

Gating mechanisms of Ano1

Ano1 is gated by both voltage and Ca2+ but examination of the sequence of Ano1 gives few clues about the sites that sense voltage or bind to Ca2+. Unlike voltage-gated channels that have amphipathic transmembrane helices with charged amino acids that serve to sense voltage, Ano1 has no such sequences. Furthermore, there are no obvious E–F hands that might serve as Ca2+ binding sites or definitive IQ domains for CaM binding. The first intracellular loop, between TMD2 and TMD3, has a large number of acidic amino acids including a stretch of 5 consecutive glutamates (444EEEEE448) that have attracted attention as a possible Ca2+ sensor35. The last glutamate in this sequence is the first residue of a 4-amino acid alternatively-spliced segment (448EAVK451). Neutralization of the glutamates has little effect on Ca2+ sensitivity, although deletion of the alternatively-spliced segment (ΔEAVK) alters both voltage-dependent gating and Ca2+ sensitivity33, 35. Thus, although the first intracellular loop plays an important role in coupling both voltage and Ca2+ binding to channel opening, it is unlikely to be the binding site for Ca2+.

If Ano1 has no Ca2+ binding site, perhaps the Ca2+ binding site is located on an accessory subunit, such as calmodulin (CaM). A recent paper reports that CaM binds to a 22-amino acid region that overlaps with the b segment in the N-terminus called CaM-BD1 and is “essential” for gating Ano136. This putative CaM binding site is not canonical, but resembles some other CaM binding sites. However, only the Ano1 splice variants containing the b segment (eg; Ano1abc) seems to require CaM. Ano1ac, which lacks the CaM-BD1, does not require CaM and is activated directly by Ca2+. It is curious that deletion of the b segment reveals a Ca2+ binding site that is suppressed in the variant having the CaM binding domain. Clearly, additional work is required to clarify the role of CaM in regulation of Ano1. Some endogenous CaCCs are regulated directly by Ca2+ and others by CaM-dependent pathways2, 37, 38 and this may be explained by expression of different splice variants or isoforms. For example, the Ca2+-sensitivity of the CaCC in olfactory receptor neurons, which is now thought to be Ano2, is decreased by a factor of ∼2 by over-expression of dominant-negative inactive CaMs, but CaM is not essential for activation38.

Functions of Tmem16/Ano paralogs

Anoctamins display differential temporal and spatial expression in a variety of developing tissues, suggesting they may play an important role in development39, 40, 41. In murine tissues, Anos 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 are expressed in a variety of epithelia, while Anos 2, 3, 4, and 5 are more restricted to neuronal and musculoskeletal tissues42. Ano1 and Ano2 are the only two members of the family that have been shown conclusively to be CaCCs.

Ano1 is ubiquitously expressed

Ano1 is widely expressed in virtually every kind of secretory epithelium, for example, salivary gland, pancreas, gut, mammary gland, and airway epithelium18, 19, 43, 44, 45, 46. Ano1 knockout mice display defective Ca2+ dependent Cl- secretion in a variety of epithelia44, 45, 46 and Ano1 has been implicated in rotovirus-induced diarrhea47. In addition, Ano1 is expressed in a variety of other cell types including certain smooth muscles and sensory neurons.

Ano1 is a secondary Cl− channel in airway

The major Cl− channel in human airway is cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), the protein that is defective in cystic fibrosis. CaCCs have long been considered as a potential target for therapy of cystic fibrosis based on the idea that upregulation or activation of CaCCs might compensate for loss of CFTR in airway fluid secretion48. Two drugs that activate CaCCs by elevating intracellular Ca2+ are presently in clinical trials for treating cystic fibrosis49, 50. Recently, however, Namkung et al51 showed that novel Ano1 inhibitors were rather ineffective in inhibiting CaCCs in airway epithelial cells despite their efficacy in inhibiting heterologously expressed Ano1 as well as native CaCCs in salivary gland. This result is puzzling in light of the reports by several groups that Ano1 is expressed in airway epithelium and that knockout of Ano1 decreases airway secretion43, 44, 46. One possible explanation is that that Ano1 in airway is a different splice variant or has other accessory proteins that alters its pharmacological profile. Cystic fibrosis affects other tissues in addition to airway — reproductive tract, pancreas, bile duct. Ano1 is expressed in all of these tissues and may be an alternate, non-CFTR Cl− secretory pathway43, 44, 52. Although Ano1 may represent a potential target for pharmacological treatment of cystic fibrosis, one serious concern is the fact that Ano1 is so widely expressed that systemically administered drugs are likely to have widespread side-effects. Thus, it seems that any therapy that targets Ano1 may require local delivery protocols. However, the differential sensitivity of airway and salivary gland CaCCs to novel Ano1 inhibitors raises the prospect that development of subtype-specific drugs may be feasible.

Ano1 is essential for gut motility

In addition to epithelia, Ano1 is robustly expressed in interstitial cells of Cajal which are responsible for generating pacemaker activity in smooth muscle of the gut43, 53, 54. Mice homozygous for a null allele of Ano1 fail to develop slow wave activity in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. The resulting loss of gastrointestinal motility may be an important contributor to the early death of Ano1 knockout mice43 and decreased expression of Ano1 in interstitial cells of Cajal may contribute to gastroparesis common in diabetic patients55.

Ano1 is expressed in certain smooth muscle cells

Ano1 is also expressed robustly in various kinds of smooth muscle including vascular smooth muscle cells43, 56, 57. Treatment of rat pulmonary aortic smooth muscle cells with siRNA against Ano1 results in a reduction of CaCCs56. Ano1 is also strongly expressed in airway smooth muscle cells, suggesting the possibility that this channel might be involved in asthma. Asthma is characterized by disorders of smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling and remodeling of the airway smooth muscle58. Considering that Ano1 is Ca2+-regulated and implicated in tracheal development40, a role for Ano1 in asthma deserves attention.

Ano1 overexpression is associated with cancer

Ano1 originally attracted the interest of cancer biologists because it is upregulated in several cancers59, 60, 61. Oncologists have recognized Ano1 by several other names including DOG1 (Discovered On GIST-1 tumor), ORAOV2 (Oral cancer Overexpressed), and TAOS-2 (Tumor Amplified and Overexpressed). Ano1 may prove a useful tool for the diagnosis of certain cancers. Gene expression profiling identified Ano1 as being highly expressed in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). KIT immunoreactivity has traditionally been used to differentiate GISTs from other tumors that are morphologically similar62. While KIT staining is highly specific for GISTs, not all GISTs display KIT immunoreactivity. Ano1 very specifically identifies a higher percentage of GIST tumors than does KIT, indicating that Ano1 may be a more robust and sensitive diagnostic biomarker for GISTs63, 64.

In both oral and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, amplification of the Ano1 locus is correlated with a poor outcome61, 65. Ano1 expression is significantly increased in patients with a propensity to develop metastases. Given the role that Cl− channels play in cell proliferation and migration, it is possible that Ano1 overexpression provides a growth or metastatic advantage to cancer cells66. Supporting the role of Ano1 in metastasis is that overexpression of Ano1 stimulates cell movement67. In contrast, silencing of Ano1 decreases cell migration; treatment of cells with CaCC blockers has a similar effect. Overexpression of Ano1 has no marked effect on cell proliferation. Although evidence suggests Ano1 may have a role in metastases, it is still possible that the chromosomal region containing Ano1 (11q13) contains other genes involved in cancer progression.

Ano1 may be involved in nociception

Ano1 is expressed in small dorsal root ganglion neurons and is implicated in mediating nociceptive signals triggered by bradykinin11. Bradykinin is a very potent inflammatory and pain-inducing substance that is released at sites of tissue damage or inflammation. Bradykinin acts on Gq-coupled B2 receptors to stimulate phospholipase-C, IP3 production, and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. The elevation of intracellular Ca2+ opens CaCCs apparently encoded by Ano1. CaCC current, along with KCNQ channel activation, depolarizes and increases AP firing. Local injection of CaCC inhibitors attenuates the nociceptive effect of local injections of BK.

Ano2 plays a role in sensory transduction

In olfactory sensory neurons, odorants open cyclic nucleotide gated channels by binding to G-protein coupled olfactory receptors that elevate cAMP6. Ca2+ influx through the cyclic nucleotide gated channels then activates CaCCs that amplify the receptor potential. From immunostaining studies, it was first suggested that Best2 might be the olfactory CaCC68, but electrophysiological recordings from Best2 knockout mice failed to confirm a role for Best2 in mediating the olfactory receptor potential69, 70. It seems Ano2 is now the best candidate for the pore-forming subunit of CaCCs in olfactory sensory neurons5, 6, 7, 71. Ano2 generates Ca2+ activated chloride currents when expressed in heterologous systems20, 72. Ano2 is localized in the cilia and dendritic knobs of olfactory sensory neurons and displays electrophysiological properties similar to native olfactory CaCCs. Ano2 displays similar halide permeability, Ca2+ sensitivity, single-channel conductance, and rundown kinetics to native olfactory CaCCs5. However, there are differences in channel inactivation kinetics, suggesting the possible presence of other regulatory subunits.

Release of the neurotransmitter glutamate at photoreceptor synapses is controlled by intracellular Ca2+. Ca2+-activated Cl− channels located in photoreceptor nerve terminals14, 73 have been shown to provide a feedback control on transmitter release74. Ano2 is highly expressed in photoreceptor synaptic terminals8. Ano2 is localized to presynaptic membranes in ribbon synapses, where it co-localizes with the adapter proteins PSD95, MPP4, and VELI3. Ano2 contains a consensus C-terminal PDZ class I binding motif that interacts with the PDZ domains of PSD95. Through this interaction, Ano2 is tethered to membrane domains along photoreceptor terminals, and may serve to regulate synaptic output in these cells. Ano1 has also been shown to be expressed in photoreceptor terminals, suggesting there may be a contribution by both proteins to CaCCs in photoreceptors74.

Are Ano3-Ano10 chloride channels?

With the exception of Ano1 and Ano2, the status of other anoctamin family members as channels is unclear. In the hands of many investigators, including ourselves, many of the heterologously-expressed Anos 3–10 do not produce robust currents because they are not readily trafficked to the plasma membrane. This could indicate that they have intracellular functions or are simply missing the necessary chaperone subunits to help them to the surface. In a study by Scheiber et al42, it was concluded that in addition to Ano1 and Ano2, Anos 6, 7, and 10 were Cl− channels. However, in iodide flux assays, the ATP- or ionomycin-stimulated flux reported for Anos 6, 7, and 10 were <10% of those for Ano1. Furthermore, the short form of Ano7 (Ano7S), which is a 179 amino acid protein with no predicted transmembrane domains and very unlikely to be an ion channel, produced approximately the same flux as the long form of Ano7. No patch clamp data were reported for Ano7. Over-expression of Ano10 produced a Cl− current that was activated slowly over a time frame of 10 min. However, expression of Ano10 also suppressed maximal currents produced by Ano1. To date, no functional data have been published for Anos 3 and 4. Recently, Ano6 was reported by another lab to be a non-selective cation channel that is more permeable to Ca2+ than Na2+ 75. It will be interesting to discover the functions of these proteins.

Ano5 mutations are linked to musculoskeletal disorders

Mutations in Ano5 result in a spectrum of musculoskeletal disorders. Ano5 was originally identified as GDD1, the gene product mutated in a rare autosomal dominant skeletal syndrome called gnathodiphyseal dysplasia (GDD)76. Mutations in cysteine-356, a highly conserved cysteine in the first extracellular loop of Ano5, results in abnormal bone mineralization and bone fragility. Ano5 resides predominantly in intracellular membrane vesicles, but the nature of these compartments is still unknown77. Although the function of Ano5 remains to be determined, it clearly plays important roles in musculoskeletal development. Ano5 is expressed in growth-plate chondrocytes and osteoblasts at sites of active bone turnover, indicating an important role in bone formation. Ano5 is also expressed in somites and in developing skeletal muscle, and is upregulated during the skeletal muscle cell line C2Cl2 myogenic differentiation.

The importance of Ano5 in skeletal muscle physiology is further highlighted by the recent finding that mutations in Ano5 produce several recessive muscular dystrophies78, 79, 80. Patients with a proximal limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD2L) and distal non-dysferlin Miyoshi myopathy (MMD3) carry mutations in Ano5. These mutations include a splice site and base pair duplication that result in premature stop codons, and two misense mutations, R758C and G231V. The phenotypes resulting from these mutations are reminiscent of dysferlinopathies, in which a deficiency in dysferlin causes defective skeletal muscle membrane repair. It has been suggested that chloride currents are important in membrane repair81 and Ano5 may be one of the channels involved in this process. Additional evidence implicating Ano5 in the maintenance of skeletal muscle is that Ano5 expression is increased in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice, a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In contrast to the Duchenne muscular dystrophy phenotype, dystrophin-deficient mdx mice maintain their ability to regenerate muscle fibers and have reduced endomysial fibrosis82. The role of Ano5 in muscle membrane repair is still speculative, but determining if Ano5 functions as a chloride channel will be critical for elucidating its role in musculoskeletal pathologies (Figure 1).

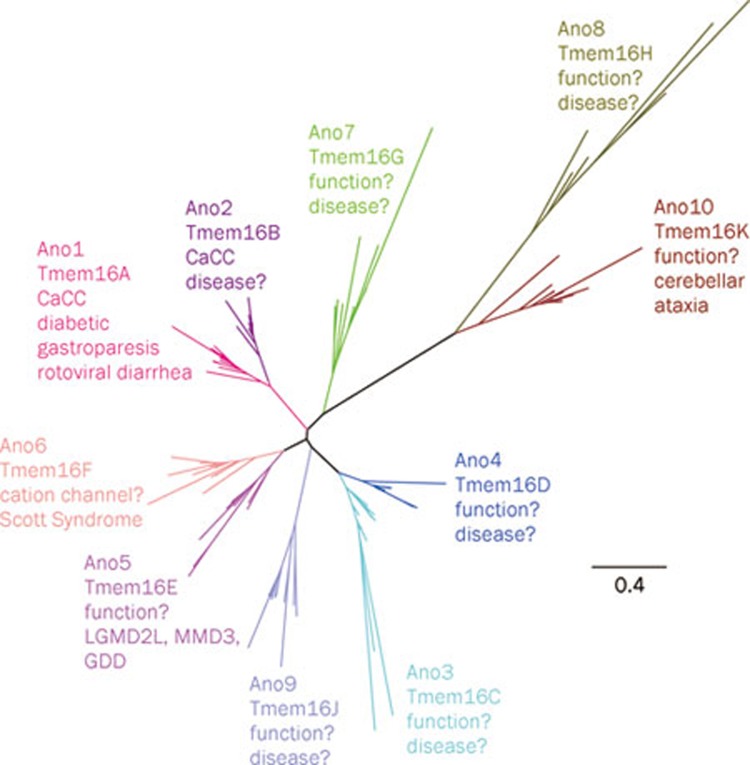

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of vertebrate Anoctamins. Each branch is labeled with the Ano and Tmem16 nomenclature, followed by the known or suspected physiological function, and any diseases that have been associated with this protein. GDD: gnathodiphyseal dysplasia; LGMD2L: proximal limb girdle muscular dystrophy; MMD3: distal Miyoshi muscular dystrophy. The tree was computed using 103 vertebrate Anoctamins found in Genbank and Ensembl using nearest neighbor statistics.

Ano6 plays a role in blood clotting

Mutations in Ano6 have recently been implicated in Scott syndrome, a rare congenital bleeding disorder caused by a defect in blood coagulation83. In platelets, like other cell types, phosphatidylserine is located on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. When platelets are activated they expose phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane to promote clotting. This redistribution of phosphatidyl-serine is mediated by phospholipid scramblases that transport phospholipids bildirectionally from one leaflet to the other. In patients with Scott syndrome this mechanism is defective, resulting in impaired blood clotting. Ano6 was found to be critical for Ca2+ dependent exposure of phosphatidylserine on the cell surface in Ba/F3 platelet cells. Furthermore, a patient with Scott syndrome harbored a mutation at a spice-acceptor site of Ano6, resulting in premature termination of the protein. Cells derived from this patient did not expose phosphatidylserine in response to a Ca2+ ionophore, unlike cells derived from the patient's unaffected parents. These data imply that Ano6 is required for scramblase activity. However, the recent finding that Ano6 is a non-selective cation channel75 throws another wrinkle into the interpretation of these data.

Ano7 is highly expressed in prostate

Ano7, which is highly expressed in prostate, was discovered in a search for genes whose expression patterns mimicked those of known prostate cancer genes34, 84. Of 40 000 human genes examined, 8 novel genes, including Ano7, were identified as being the most closely linked to known prostate cancer genes. Ano7 is expressed on the apical and lateral membranes of normal prostate. In the prostate LNCaP cell line stably transfected with Ano7, the protein localizes to cell-cell contact regions. It has been suggested that Ano7 promotes cell association because cell association can be reduced with RNAi targeted to Ano784. The predominant expression in prostate and prostate cancers poise Ano7 as an attractive candidate for immunotherapy85, 86, although the role of Ano7 in the development of prostate cancer is uncertain.

Ano10 mutations are linked to ataxia

Mutations in Ano10 have been linked to autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxias associated with moderate gait ataxia, downbeat nystagmus, and dysarthric speech87. Affected individuals display severe cerebellar atrophy. Two of the mutations introduce premature stop codons, probably leading to null protein expression. The other mutation is a missense mutation, L510R, which is highly conserved among the Anos and lies in the sixth transmembrane domain within the DUF590 domain of unknown function. It remains especially uncertain whether Ano10 is an ion channel, because Ano10 and Ano8 constitute the most divergent branch of the anoctamin family. While there is little functional data for Ano10, a Drosophila ortholog of Ano8/10, called Axs, is necessary for normal spindle formation and cell cycle progression88. Axs co-localizes with ER components, and is recruited to microtubules of assembling spindles during mitosis and meiosis. A dominant mutation in Axs causes abnormal segregation of homologous achiasmate chromosomes due to defects in spindle formation, and disrupts cell cycle progression. It remains to be seen if Ano10 plays a similar role in mammalian systems.

Summary

The Tmem16/Anoctamin family promises to reveal many exciting secrets over the next few years. We are impatient to know whether Anos3–10 are anion channels, other types of channel, or something else, such as a phospholipid scramblase. We would also like to know whether some of these proteins have functions in intracellular organelles. It is interesting that in just ∼3 years since Ano1 and Ano2 were identified as CaCCs, Anos 5, 6, and 10 have been linked to several serious human diseases, but human diseases caused by mutations in Ano1 and Ano2 have not been found. Certainly in the case of Ano1, this may be because these mutations are lethal, just as the null allele is in mice40. The location of the pore of the Ano1 channel still has not been clearly established. Although mutations between TMD5 and TMD6 point to the putative re-entrant loop here as being part of the pore18, 19, the remarkably high conservation in this region between Ano1, which is an anion channel, and Ano6, which is apparently a cation channel, argues against this region as a determinant of ion selectivity. Unravelling the mechanisms of Ano1 regulation by Ca2+ and voltage also remain areas that are certain to provide exciting insights.

Acknowledgments

The work in the authors' lab is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants RO1-GM60448, RO1-EY014582, and P30-EY006360. Charity DURAN is supported by an NIH Training Grant T32-EY007092.

The authors would like to thank Drs Qing-huan XIAO, Kuai YU, Patricia PEREZ-CORNEJO, and Jorge ARREOLA for helpful discussion and comments.

References

- Duran C, Thompson CH, Xiao Q, Hartzell HC. Chloride channels: often enigmatic, rarely predictable. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:95–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarran R. Regulation of airway surface liquid volume and mucus transport by active ion transport. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:42–6. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarran R, Loewen ME, Paradiso AM, Olsen JC, Gray MA, Argent BE, et al. Regulation of murine airway surface liquid volume by CFTR and Ca2+–activated Cl− conductances. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:407–18. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan AB, Shum EY, Hirsh S, Cygnar KD, Reisert J, Zhao H. ANO2 is the cilial calcium–activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11776–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903304106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengl T, Kaneko H, Dauner K, Vocke K, Frings S, Mohrlen F. Molecular components of signal amplification in olfactory sensory cilia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6052–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909032107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasche S, Toetter B, Adler J, Tschapek A, Doerner JF, Kurtenbach S, et al. Tmem16b is specifically expressed in the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons. Chem Senses. 2010;35:239–45. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohr H, Heisig JB, Benz PM, Schoberl S, Milenkovic VM, Strauss O, et al. TMEM16B, a novel protein with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity, associates with a presynaptic protein complex in photoreceptor terminals. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6809–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5546-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C435–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. Phenomics of cardiac chloride channels: the systematic study of chloride channel function in the heart. J Physiol. 2009;587:2163–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Linley JE, Du X, Zhang X, Ooi L, Zhang H, et al. The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M-type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1240–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI41084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish ME. A transient calcium-dependent chloride current in the immature Xenopus oocyte. J Physiol. 1983;342:309–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R. A calcium-dependent transient outward current in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;215:491–7. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader CR, Bertrand D, Schwartz EA. Voltage–activated and calcium-activated currents studied in solitary rod inner segments from the salamander retina. J Physiol. 1982;331:253–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Liu J, Di A, Robinson NC, Musch MW, Kaetzel MA, et al. Regulation of human CLC-3 channels by multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20093–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen ME, Forsyth GW. Structure and function of CLCA proteins. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1061–92. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell HC, Qu Z, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:639–72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic VM, Brockmann M, Stohr H, Weber BH, Strauss O. Evolution and functional divergence of the anoctamin family of membrane proteins. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CA, Cid LP, Sepulveda FV, Niemeyer MI. TMEM16 proteins: the long awaited calcium–activated chloride channels. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42:993–1001. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009005000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta LJ. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels. Biophys J. 2009;97:3047–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L, Caputo A, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A protein: a new identity for Ca2+–dependent Cl channels. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:357–63. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00030.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin / TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Physiol Online. 2009;587:2127–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Kongsuphol P, Aldehni F, Tian Y, Ousingsawat J, Warth R, et al. Bestrophin and TMEM16-Ca2+ activated Cl− channels with different functions. Cell Calcium. 2009;46:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AP. Cloning and expression of a calcium-activated chloride channel reveal a novel protein candidate. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:393–4. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.6.7648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo BE, Vacquier VD. Phylogeny of the TMEM16 protein family: some members are overexpressed in cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:919–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Kongsuphol P, Chootip K, Toledo C, Martins JR, Almaca J, et al. Role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channels bestrophin and anoctamin in epithelial cells. Biol Chem. 2011;392:125–34. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Hahn Y, Walker DA, Nagata S, Willingham MC, Peehl DM, et al. Topology of NGEP, a prostate-specific cell:cell junction protein widely expressed in many cancers of different grade level. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6306–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan JT, Worthington EN, Yu K, Gabriel SE, Hartzell HC, Tarran R. Characterization of the oligomeric structure of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel Ano1/TMEM16A. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1381–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.174847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah G, Romer T, Detro-Dassen S, Braam U, Markwardt F, Schmalzing G. TMEM16A(a)/anoctamin-1 shares a homodimeric architecture with CLC chloride channels. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110.004697. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, et al. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33360–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera TK, Das S, Maeda H, Beers R, Wolfgang CD, Kumar V, et al. NGEP, a gene encoding a membrane protein detected only in prostate cancer and normal prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308746101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q, Yu K, Perez–Cornejo P, Cui Y, Arreola J, Hartzell HC.Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of tmem16a/ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102147108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tian Y, Kongsuphol P, Hug M, Ousingsawat J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, et al. Calmodulin-dependent activation of the epithelial calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16A. FASEB J. 2011;25:1058–68. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Differences in regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in colonic and parotid secretory cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C161–C166. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko H, Mohrlen F, Frings S. Calmodulin contributes to gating control in olfactory calcium–activated chloride channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:737–48. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli-Linde A, Vaziri Sani F, Rock JR, Hallberg K, Iribarne D, Harfe BD, et al. Expression patterns of the Tmem16 gene family during cephalic development in the mouse. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:178–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, Futtner CR, Harfe BD. The transmembrane protein TMEM16A is required for normal development of the murine trachea. Develop Biol. 2008;321:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, Harfe BD. Expression of TMEM16 paralogs during murine embryogenesis. Develop Dynamics. 2008;237:2566–74. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R, Uliyakina I, Kongsuphol P, Warth R, Mirza M, Martins JR, et al. Expression and function of epithelial anoctamins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7838–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Cheng T, Huang X, Jan YN, et al. Studies on expression and function of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911935106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ousingsawat J, Martins JR, Schreiber R, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Kunzelmann K. Loss of TMEM16A causes a defect in epithelial Ca2+-dependent chloride transport. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28698–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko VG, Catalan MA, Brown DA, Putzier I, Hartzell HC, Marmorstein AD, et al. Tmem16A encodes the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in mouse submandibular salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12990–3001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, O'Neal WK, Gabriel SE, Randell SH, Harfe BD, Boucher RC, et al. Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A) is a Ca2+-regulated Cl− secretory channel in mouse airways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14875–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ousingsawat J, Mirza M, Tian Y, Roussa E, Schreiber R, Cook DI, et al. Rotavirus toxin NSP4 induces diarrhea by activation of TMEM16A and inhibition of Na+ absorption. Pflugers Arch. 2011;461:579–89. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MR, Clarke LL, Boucher RC. Extracellular ATP and UTP induce chloride secretion in nasal epithelia of cystic fibrosis patients and normal subjects in vivo. Chest. 1992;101:60S–63S. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.3_supplement.60s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin PL, Boyle MP, Guggino WB, Molina L. A phase I trial of intranasal Moli1901 for cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2004;125:143–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey S, Wald G. Novel agents in cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:555–6. doi: 10.1038/nrd2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2365–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta AK, Khimji AK, Kresge C, Bugde A, Dougherty M, Esser V, et al. Identification and functional characterization of TMEM16A, a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel activated by extracellular nucleotides, in biliary epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:766–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Britton FC, O'Driscoll KE, Hennig G, Bayguinov YR, et al. Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal muscles. J Physiol. 2009;587:4887–904. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MH, Kim TW, Ro S, Yan W, Ward SM, Koh SD, et al. A Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in interstitial cells of Cajal linked to slow wave currents and pacemaker activity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4905–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone A, Bernard CE, Strege PR, Beyder A, Galietta LJ, Pasricha PJ, et al. Altered expression of ANO1 variants in human diabetic gastroparesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13393–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P. TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium-activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:2305–14. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AJ, Forrest AS, Jepps TA, Valencik ML, Wiwchar M, Singer CA, et al. Expression profile and protein translation of TMEM16A in murine smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C948–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00018.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahn K, Ojo OO, Chadwick G, Aaronson PI, Ward JP, Lee TH. Ca2+ homeostasis and structural and functional remodelling of airway smooth muscle in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:547–52. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RB, Corless CL, Chen X, Rubin BP, Subramanian S, Montgomery K, et al. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:107–13. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Gollin SM, Raja S, Godfrey TE. High-resolution mapping of the 11q13 amplicon and identification of a gene, TAOS1, that is amplified and overexpressed in oral cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11369–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172285799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles A, Millon R, Cromer A, Ganguli G, Lemaire F, Young J, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma transcriptome analysis by comprehensive validated differential display. Oncogene. 2006;25:1821–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa I, Lee CH, Kim MK, Rouse BT, Subramanian S, Montgomery K, et al. A novel monoclonal antibody against DOG1 is a sensitive and specific marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:210–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181238cec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DG, Qian X, Hornick JL. DOG1 antibody is a highly sensitive and specific marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in cytology cell blocks. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:448–53. doi: 10.1309/AJCP0PPKOBNDT9LB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Liang CW, Espinosa I. The utility of discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumor 1 (DOG1) antibody in surgical pathology–the GIST of it. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:222–32. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181d973c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Godfrey TE, Gooding WE, McCarty KS, Jr, Gollin SM. Comprehensive genome and transcriptome analysis of the 11q13 amplicon in human oral cancer and synteny to the 7F5 amplicon in murine oral carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1058–69. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K. Ion channels and cancer. J Membr Biol. 2005;205:159–73. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub C, Wasylyk C, Li Y, Thomas E, Marisa L, Robe A, et al. ANO1 amplification and expression in HNSCC with a high propensity for future distant metastasis and its functions in HNSCC cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:715–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S, Pascarella G, Boccaccio A, Mazzatenta A, Gustincich S, Menini A, et al. Bestrophin-2 is a candidate calcium-activated chloride channel involved in olfactory transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604505103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S, Dibattista M, Sagheddu C, Boccaccio A, Al Qteishat A, Ghirardi F, et al. Calcium-activated chloride currents in olfactory sensory neurons from mice lacking bestrophin-2. J Physiol. 2009;587:4265–79. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakall B, McLaughlin PJ, Stanton JB, Hartzell HC, Marmorstein LY, Marmorstein AD. The bestrophin-2 knock-out mouse: histological and functional analysis. ARVO Meeting Abstracts. 2007;48:2983. [Google Scholar]

- Sagheddu C, Boccaccio A, Dibattista M, Montani G, Tirindelli R, Menini A. Calcium concentration jumps reveal dynamic ion selectivity of calcium-activated chloride currents in mouse olfactory sensory neurons and TMEM16b-transfected HEK 293T cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:4189–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S, Dibattista M, Menini A. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:1023–38. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeish PR, Nurse CA. Ion channel compartments in photoreceptors: evidence from salamander rods with intact and ablated terminals. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:86–95. doi: 10.1152/jn.00775.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer AJ, Rabl K, Riccardi GE, Brecha NC, Stella SL, Jr, Thoreson WB. Location of release sites and calcium-activated chloride channels relative to calcium channels at the photoreceptor ribbon synapse. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:321–35. doi: 10.1152/jn.00332.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Jin T, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Scan: a novel small-conductance Ca2+-activated non-selective cation channel encoded by TMEM16F. Biophys J. 2011;100:259a. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi S, Kamata N, Vokes TJ, Maruoka Y, Nakakuki K, Enomoto S, et al. The novel gene encoding a putative transmembrane protein is mutated in gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia (GDD) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1255–61. doi: 10.1086/421527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta K, Tsutsumi S, Inoue H, Sakamoto Y, Miyatake K, Miyawaki K, et al. Molecular characterization of GDD1/TMEM16E, the gene product responsible for autosomal dominant gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks D, Sarkozy A, Muelas N, Koehler K, Huebner A, Hudson G, et al. A founder mutation in Anoctamin 5 is a major cause of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Brain. 2011;134:171–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolduc V, Marlow G, Boycott KM, Saleki K, Inoue H, Kroon J, et al. Recessive mutations in the putative calcium-activated chloride channel Anoctamin 5 cause proximal LGMD2L and distal MMD3 muscular dystrophies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjneh I, Jaiswal J, Lamminen A, Somer M, Marlow G, Kiuru–Enari S, et al. A new distal myopathy with mutation in anoctamin 5. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:791–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.07.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein A, Terasaki M. Rapid increase in plasma membrane chloride permeability during wound resealing in starfish oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:151–9. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P, Geng Y, Ryder–Cook AS, Barnard EA, Darlison MG, Barnard PJ. The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science. 1989;244:1578–80. doi: 10.1126/science.2662404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Umeda M, Sims PJ, Nagata S. Calcium-dependent phospholipid scrambling by TMEM16F. Nature. 2010;468:834–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Hahn Y, Nagata S, Willingham MC, Bera TK, Lee B, et al. NGEP, a prostate-specific plasma membrane protein that promotes the association of LNCaP cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1594–601. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda V, Poole DJ, Palena C, Das S, Bera TK, Remondo C, et al. New gene expressed in prostate: a potential target for T cell-mediated prostate cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0723-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM, Naz RK. Novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for prostate cancer. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2010;2:677–84. doi: 10.2741/s93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer S, Hoischen A, Meijer RP, Gilissen C, Neveling K, Wieskamp N, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of a 12.5 Mb homozygous region reveals ANO10 mutations in patients with autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Hawley RS. The spindle-associated transmembrane protein Axs identifies a membranous structure ensheathing the meiotic spindle. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:261–3. doi: 10.1038/ncb944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]