Abstract

The development of efficient microbicides, the topically applied compounds that protect uninfected individuals from acquiring HIV-1, is a promising strategy to contain HIV-1 epidemics. Such microbicides should of course possess anti-HIV-1 activity, but they should also act against other genital pathogens, which facilitate HIV-1 transmission. The new trend in microbicide strategy is to use drugs currently used in HIV-1 therapy. The success of this strategy is mixed so far and is impaired by our limited knowledge of the basic mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission as well as by the inadequacy of the systems in which microbicides are tested in pre-clinical studies.

Keywords: Microbicide, HIV-1, Tenofovir, Pre-exposure prophylaxis

Microbicides: definition and sites of action

To date, the majority of newly HIV-1-infected individuals worldwide acquire HIV-1 through sexual transmission when the virus crosses mucosal surfaces. Therefore, an understanding of the mechanisms of HIV-1 mucosal transmission is critical to the development of means to prevent it. Recently, the diminution of the HIV-1 load of an infected partner to levels at which transmission becomes inefficient was demonstrated to be a successful preventive strategy [1]. However, this strategy leaves prevention measures in the hands of the infected donor, while it is necessary to give power also to the uninfected partners, especially to women. Microbicides as well as oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and preventive vaccines, if developed, provide such power.

Microbicides are compounds that are applied topically aiming at protecting individuals from acquiring pathogenic microbes, in particular HIV-1. Despite the semantics of a word that includes ‘cide’ (the suffix originates from Latin caedere ‘to kill’), the above definition of microbicide does not require actual ‘killing’ of a microbe but includes compounds that may act through other mechanisms, e.g., by blocking viral entry or suppressing initial steps of the viral reproductive cycle (Figure 1).

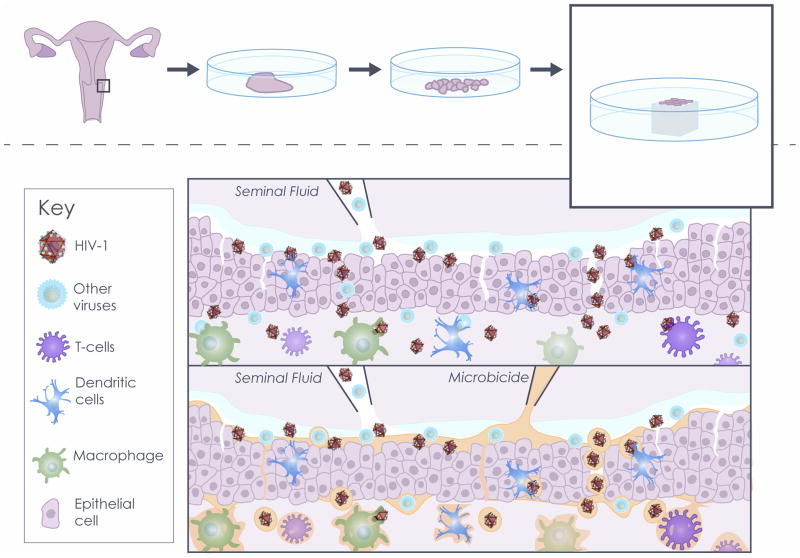

Figure 1. Use of human cervico-vaginal tissue ex vivo as a microbicide testing platform.

Upper panel: Human tissue explants cultured ex vivo serve as a model for HIV-1 transmission. Briefly, human cervico-vaginal tissues obtained from surgery are dissected into tissue blocks, which are cultured at the liquid-air interface. Transmissions of HIV-1 and HIV-1 copathogens are simulated by applying viral suspensions in seminal fluid. This model simulates some of the in vivo mechanisms by which HIV-1 penetrates cervico-vaginal mucosa and infects cell targets.

Lower panel: A human cervico-vaginal tissue system complemented with seminal fluid is used as a platform to test microbicides. Microbicides may prevent HIV-1 transmission by inactivating pathogens, preventing viral entry, and suppressing HIV-1 infection of target cells.

Mucosal sites critical for HIV-1 transmission to which microbicides should be applied are cervico-vaginal, penile, and rectal mucosa. Here, we predominantly limit ourselves to the discussion of microbicides that aim at preventing male-to-female HIV-1 transmission via the female genital tract. However, rectal microbicides should also remain a main focus of interest as unprotected receptive anal sex, which is practiced by both men and women, is associated with the highest probability of sexual HIV-1 transmission [2–3].

HIV-1 transmission through cervico-vaginal mucosa

HIV-1 male-to-female cervico-vaginal transmission is a complex phenomenon, and despite many efforts its basic mechanisms are still poorly understood. It is believed that the cervico-vaginal mucosa constitutes a strong natural barrier against HIV-1 and other pathogens [4]. Although HIV-1 may enter through transcytosis (better studied in the gut) [5] or be carried through the mucosa by epithelial Langerhans cells [6], experimental data suggest that HIV-1 penetrates the female lower genital tract epithelial layer inefficiently unless the tract is damaged by lesions of various natures (Figure 1) [7]. Unfortunately, lesions in the female genital tract are common and some of them can result from sexual intercourse [8].

Furthermore, the vulnerability of the lower female genital tract to HIV-1 is heterogeneous in space and time: while the vagina and ectocervix, the forefront barriers against the virus, are composed of multiple layers of stratified squamous epithelium, the endocervix is composed of a single epithelial monolayer [9]. It is believed that the transition area between the ecto- and endocervix is one of the most common sites for HIV-1 transmission (see [10]). Moreover, in different phases of the menstrual cycle the thickness of the epithelium varies. Elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase lead to thinning of epithelia, increasing organ susceptibility to HIV-1 [11].

Also, various genital pathogens, including bacteria and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), cause inflammation and facilitate infection by thinning and disrupting the multilayered lining, recruiting a pool of target cells for local HIV-1 expansion and interfering with innate antimicrobial activity (see [12]). Therefore, the ideal microbicide should not only be active against HIV-1 but also against HIV-1 copathogens, most importantly HSV-2. A better understanding of the initial steps of HIV-1 mucosal infection and the role of other genital pathogens in HIV-1 transmission will help to identify when HIV-1 is most vulnerable to potential microbicides as it enters the host [13].

Microbicides: past failures and a current success

Microbicide development began more than 20 years ago with the intention of developing a spermicidal vaginal gel active against sexually transmitted infections, including HIV-1. Since then, microbicide compounds have been formulated not only as gels but also as creams, vaginal rings, tablets, foams, films, and suppositories [14].

Early microbicides were based on non-specific surfactants, polyanions, and vaginal milieu protectors. The history of early surfactant-based microbicides was stained with disappointments, as nonoxynol-9 (N9), successfully tested in vitro [15] and in animals [16], increased HIV-1 susceptibility in the Phase III clinical trial [17]. Also, a trend towards an increase of infection rates among participants was noticed in a clinical trial of another surfactant, Savvy (C31G) [18–19]. Two polyanion-based microbicides (VivaGel™ and Dextrin Sulfate) are currently in PhaseI/II clinical trials [20–22]. Other polyanion-based microbicides (PRO2000, cellulose sulfate, carraguard), which prevent HIV-1 from binding to and entering target cells, although active in vitro [23–24], repeatedly and disappointingly failed to prevent HIV-1 acquisition in the Phase III trials [25–28].

Thus, the problems with these microbicides were not identified in pre-clinical studies, indicating that the systems in which they were tested do not faithfully reflect important aspects of the in vivo situation. For example, although non-toxic, some of these compounds may subtly disrupt cell-cell contacts in the epithelial layer, allowing the virus to go through [29]. Such effects could be hardly noticed in single-cell cultures, which poorly reflect in vivo cell-cell interactions [30]. The problem of tissue damage becomes even more important in the case of rectal microbicides, as in contrast to the vagina, the rectal mucosa consists of a single-layer columnar epithelium.

The failure of the first generations of microbicides in clinical trials indicates that compounds that do not damage tissues should be used to prevent HIV-1 transmission.

Therefore, instead of non-specific compounds, highly potent and specific anti-HIV-1 antivirals such as nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), as well as inhibitors of HIV-1integrase and protease that are currently successfully used in therapy, have recently been proposed as microbicides [31–32]. In particular, the NRTI tenofovir formulated as a 1% gel was tested in CAPRISA 004, a double-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial for prevention of HIV-1 acquisition in South African women [33]. In CAPRISA 004, 1% tenofovir gel reduced HIV-1 acquisition by an estimated 39% overall, and by 54% in women who used the gel 80% or more of the time [33].

PrEP: topical or oral?

The CAPRISA 004 findings raised enthusiasm in the scientific community, as they came as a proof-of-concept for the feasibility of preventing HIV-1 acquisition with an antiviral formulation delivered topically [33]. However, systemic drug administration has also been successful in preventing HIV-1 transmission: in the iPreX trial (PrEP Initiative), daily oral tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada®) taken by men who have sex with men and transgendered women decreased HIV incidence by 44% [34]. Since then, PrEP demonstrated efficacy in two additional studies: (i) the Partners PrEP Study in African HIV serodiscordant couples, in which the HIV-seronegative partner received daily oral tenofovir or tenofovir/emtricitabine, showed respectively 62% and 73% efficacy; (ii) the TDF2 trial in young heterosexual men and women in Botswana demonstrated 63% efficacy of daily oral Truvada®, bringing the number of successful PrEP clinical trials to four (reviewed in [35–36]).

Unfortunately, the enthusiasm has more recently been tempered by negative results: the two arms of the VOICE (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic) trial, using either tenofovir-based gel or oral tenofovir alone among African women, and the FEM-PrEP trial, using oral emtricitabine/tenofovir in heterosexual African women [37], have been halted because of futility (see [35–36]).

Although results from several of the trials are controversial, differences in the cohorts, in pharmacokinetics of tenofovir formulations, in protocols, and in adherence offer plausible explanations for the discrepancies [38]. In particular, the critical role of adherence is illustrated by the iPrEx and CAPRISA 004trials: in the iPrEX study, only three patients had detectable study drug in their plasma or peripheral mononuclear cell samples at the time of HIV infection diagnosis [34]. Overall, detectable drug levels were associated with a 12.9-fold (95% CI, 1.7 to 99.3, p<0.001) lower probability of HIV infection and a 92% (95% CI, 40 to 99, p<0.001) reduction in HIV infection compared with placebo controls [34].

In CAPRISA 004, the product’s effectiveness was also directly linked to adherence: women who used the gel 80% or more of the time had a 54% reduction in HIV-1 incidence, while women who used it less than 50% of the time had a 28% reduction in HIV-1 incidence. Moreover, the protection decreased from 50% after 12 months to 39% after 30 months of use, most likely because of a lower adherence in the second year [33]. Also, the HIV incidence rate in women with tenofovir concentrations of 1000 ng/mL or less was close to that in the placebo group (7.8 vs 9.1 per 100 women-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR]=0.86, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.35, p=0.51), while the HIV incidence rate in women with tenofovir concentrations greater than 1000 ng/mL was significantly lower than that in the placebo group (2.4 vs 9.1 per 100 person-years; IRR=0.26, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.80, p=0.01) [39]. Both inadequate drug delivery at the site of infection and poor adherence, as well as possibly other not-yet-revealed factors, are likely to be the reasons behind the failure of the FEM-PrEP and the oral TDF arm of the VOICE trial [40]. With regard to the 1% tenofovir gel arm of VOICE, it has been hypothesized that the daily use conferred a degree of difficulty that may have reduced adherence, explaining the contrasting result with CAPRISA 004, in which application of the gel was coitally-dependent [41]. The recently launched FACTS 001 study is designed to confirm the CAPRISA 004 trial’s coital use of tenofovir gel in preventing HIV-1 and HSV-2 among a more diverse population of South African women than that enrolled in CAPRISA 004.

In general, poor adherence is one of the major problems that hinder adequate evaluation of the drugs’ efficiencies, thus highlighting that adherence should be carefully evaluated. Adherence assessment based on patients’ reports or pill count seems to be unreliable. A more accurate way to assess adherence might be through measurement of drug levels [35]. Further studies are needed to determine how to maximize adherence among PrEP recipients as well as to develop adherence-independent delivery strategies, such as vaginal rings. Also, it is important to optimize drug dosing [42]. The currently ongoing HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) trial 067 is a Phase II, randomized, open-label, pharmacokinetic study of Truvada® aimed at determining dosing strategy for optimal PrEP [36].

Microbicides: new development

After the recent completed clinical trials, it is clear that antiretroviral drugs can prevent HIV infection [40]. As of now, the main drug that has been used in various combinations is tenofovir, in part because of its efficacy in suppressing viral replication and its safety profile, long half-life, and rapid absorption [38]. Also, tenofovir is being developed for a vaginal ring formulation that is currently under preclinical evaluation [35].

Other antiretrovirals currently in development into microbicides include the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors UC781 [43], dapivirine [44], and rilpivirine [45]. For example, dapivirine has been formulated for delivery with intravaginal rings. This formulation seems to be safe and well tolerated [44]. Its efficiency against HIV transmission will be tested in the MTN (Microbicides Trials Network)-020 or ASPIRE (A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use) clinical trials [35]. Rilpivirine has been prepared as a parenteral formulation for prolonged plasma exposure and is currently being evaluated for pharmacokinetics and dose ranging in early clinical trials [35].

Other antiretrovirals, such as fusion inhibitors (cyanovirin, griffithsin, and C52L) that block specific proteins on HIV-1[46–48], protease inhibitors [31], and CCR5 coreceptor inhibitors (CMPD167, PSC-RANTES and Maraviroc) [49–51], are also being developed. In particular, HPTN 069 is a Phase II randomized, double-blind clinical trial that will assess the safety and tolerability of Maraviroc; Maraviroc + emtricitabine; Maraviroc + tenofovir, and tenofovir + emtricitabine for PreEP to prevent HIV transmission in men who have sex with men (see [35]).

Finally, attempts to engineer vaginal Lactobacilli to express entry inhibitors, such as cyanovirin N and CCR5 antagonists have also been reported [52–53].

In general up to now, more than 70 preclinical microbicide trials and 50 clinical trials of different phases have been performed (see www.microbicide.org).

Dual-targeted microbicides

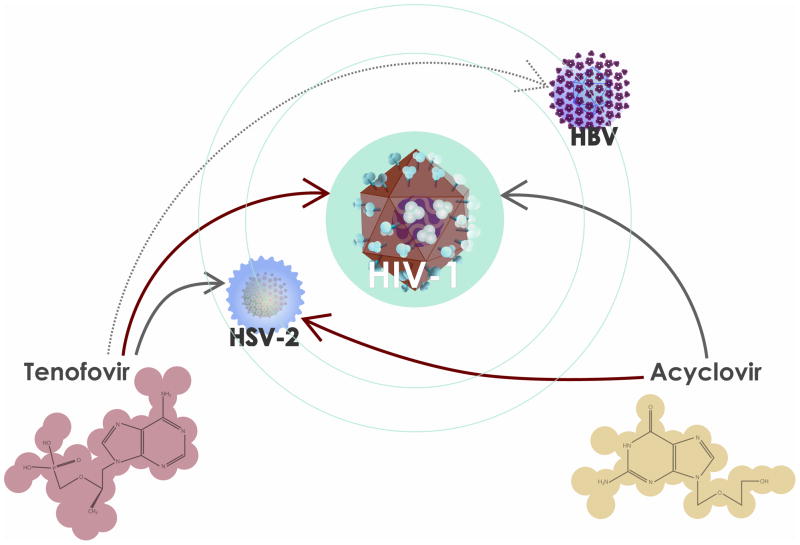

One of the important and unexpected results of CAPRISA 004 was a significant 51% reduction of the rate of acquisition of HSV-2, a common HIV-1 copathogen which facilitates HIV-1 transmission [54]. This effect was not anticipated, since in in vitro studies tenofovir showed no anti-HSV activity at the concentrations corresponding to systemic administration [55] while higher concentrations were considered to be non-physiological. In CAPRISA 004 vaginally applied tenofovir reaches concentrations that were much higher than those reached in vagina with systemic administration [39, 56]. The difference between vaginal concentrations of tenofovir when applied locally or systemically may explain why orally administrated tenofovir did not prevent HSV-2 acquisition in the iPrex trial (see [35]) or showed no effect on HSV-2 shedding [57].

Indeed, the effect of tenofovir at different concentrations was investigated in several experimental models [58–59], most importantly in explants of human cervico-vaginal tissue coinfected with HIV-1 and HSV-2 and it was demonstrated that only at high concentrations this drug has a direct antiherpetic activity [58–59]. The molecular mechanism is the following: tenofovir’s active metabolite, tenofovir diphosphate, which is efficiently generated in cells of different types, effectively inhibits HSV DNA polymerase [58].

Thus, paradoxically, while the field of HIV-1 microbicides moved from non-specific to highly specific microbicides, one of them turned out to be effective against a non-HIV-1 virus, namely HSV-2 [54].

The results with tenofovir, a drug which was designed as an anti-HIV-1 antiviral but which affects HSV-2, mirror early data on acyclovir (ACV), which was designed to suppress HSV-2 but was found to be active against HIV-1 as well [60] (Figure 2). In human herpesvirus (HHV)-infected tissues, ACV phosphorylated by HSV thymidine kinase becomes an efficient inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Accordingly, ACV inhibits HIV-1 replication in tissues infected with various HHVs, in particular HHV-6 and HHV-7 [60]. The anti-HIV-1 activity of ACV has also been demonstrated in clinical trials: when administered to HIV-1-coinfected individuals, ACV suppressed not only HSV-2 but significantly decreased HIV-1 load (reviewed in [61]). However, when used as preventive therapy in a clinical trial, ACV failed to decrease the rate of HIV-1 transmission. This may be caused by inefficient metabolism of ACV in the African women who were the subjects of this clinical trial [62]. Nevertheless, we think that ACV or its efficient prodrugs, which have yet to be developed to their full potential [63], may be active as HIV-1 microbicides in women regardless of race.

Figure 2. Dual targeted drugs as potential microbicides.

HIV-1 infection is associated with infection by copathogens that in turn may facilitate HIV-1 replication and/or transmission. Well-known specific antivirals used in therapy against particular viruses may target viruses other than the ones against which they were originally designed. Acyclovir, originally designed to suppress herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) (red arrow), suppresses HIV-1 as well. Tenofovir, originally designed against HIV-1 (red arrow), has anti-HSV-2 activity. Tenofovir also has activity against hepatitis B virus (HBV) (dotted arrow).

Microbicide testing: ex vivo systems

So far, understanding of the events leading to HIV-1 transmission comes predominantly from the non-human primate model, where it has been shown that the first target cells HIV-1 infects after crossing the epithelia are CD4 T cells, establishing a so-called founder population of infected cells [4]. Later on, this pool of primary infected cells undergoes a local expansion that is driven by the recruitment of new CD4-positive target cells to the site of infection by means of chemokines and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) [4].

To complement the studies on mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission in animal models, a laboratory-controlled experimental system to study early events of HIV-1 transmission and to test microbicides is needed. Among such systems, several dual-chamber models of the female genital mucosa have been suggested [64–66].

In our opinion, one of the most promising laboratory-controlled experimental systems to investigate early events of HIV-1 vaginal transmission is In this model, the natural cytoarchitecture of tissue and important aspects of cell physiology are preserved. This is why, in contrast to single-cell cultures, it supports replication of HIV-1 without artificial stimulation. Also, this system supports the replication of HIV-1 copathogens, providing the opportunity to study inter-viral interactions [71] and making this system an adequate platform for preclinical testing of microbicides. However, like every model, the explant model has its own limitations, which include (i) inability to regenerate or repair, (ii) lack of recruitment of immune cells, and (iii) lack of hormone modulation [30, 72].

The explant system should be developed further to reflect the in vivo situation more closely in order to become a more adequate platform for microbicide testing [66]. In particular, the changes of the vaginal mucosa microenvironment upon deposition of semen that contains a complex mixture of cytokines and microbes [73] should be simulated. It is important to test that whether in this new microenvironment the activity of the microbicide candidate is preserved. Indeed, it has been shown that semen and seminal plasma proteins interfere with the antiviral activity of several microbicides [74–75], providing partial explanation for the failure of some in vitro-effective microbicides to protect against HIV-1 in vivo [26–27]. Moreover, semen may impair general female host defenses, or it may enhance HIV-1 infectivity (reviewed in [76]). Therefore, cervico-vaginal tissue explants should be complemented with seminal fluid for adequate microbicide testing ex vivo.

A long road to an efficient microbicide: conclusions and perspectives

The so-far not highly successful history of microbicide development demonstrates the complexity of the problems that need to be resolved. Indeed, the long road to a successful microbicide should include the development of a highly efficient drug that should not alter the physiology of individual cells and of cell-cell interactions and that should prevent the virus from entering into the cells or block its replication. For instance, a microbicide should not alter vaginal microflora, in view of a recent report that provides experimental evidence that the vaginal microflora regulates the epithelial innate immunity [77]. Currently, microbicides based on the approved and efficient anti HIV-1 antiretrovirals that are used in therapy seem to be the most promising [78].

Testing potential microbicides in an adequate ex vivo tissue system that reflects not only the physiology of the tissue itself but also the microenvironment changes that could be associated with the sexual act (changing pH, modulation of chemokine spectra, effects of seminal plasma on microbicides, etc.) may reveal problems that need to be addressed before testing microbicides in animals or launching clinical trials. Using inadequate laboratory systems may result in a failure at the late stages of microbicide testing. Advanced laboratory systems include tissue explants that preserve native cytoarchitecture. However, these systems should be further developed to reflect the microenvironment and altered tissue physiology due to the mixing of body fluids during sexual intercourse. Also, laboratory systems should include small animal models such as ‘humanized mice’ [79] to complement findings on non-human primates [80].

In our opinion, the knowledge gaps in the basic mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission are among the most important obstacles in developing efficacious microbicides. For example, we are still not sure in which cases HIV-1 is transmitted as a free virus and in which as a cell-associated one, and we do not know why HIV-1-variants that use CCR5 as a coreceptor start productive infection in the recipient, while the donor’s body fluids carry both CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptor-using HIV-1 variants. Such gaps impair our strategy in developing microbicides. Should we focus on microbicides to prevent transmission of the CCR5-using variants only or transmission of the CXCR4-using ones as well? Moreover, it has been found that 80% of HIV-1 heterosexual infection is initiated by the transmission of one transmitter/founder virion [81]. This was also true for women who in CAPRISA 004 trial became seroconverted in spite of using tenofovir gel [82]. If these transmitter/founder virions are not different from the bulk of viruses present in semen and are transmitted stochastically, then the general strategies outlined above should be followed. However, if these transmitter/founder virions have specific features responsible for overcoming the mucosal defense, then we should develop new microbicides that interfere with these features and therefore specifically prevent the transmission of these viruses.

Likewise, we know too little about the role of host factors (semen, female genital tract secretions, and the physiology of mucosa and its natural defense mechanisms against pathogens developed in the course of evolution). A more detailed knowledge of the earliest stages of HIV-1 infection at the major sites of sexual HIV-1 transmission and of the mucosal responses will undoubtedly accelerate progress towards the design of safe and efficacious microbicides [12]. Also, a better knowledge of the basic mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission may result in the development of a set of (surrogate) biomarkers. Such a set of biomarkers should include various cytokines, chemokines, activation markers, and other inflammatory or protective mediators [83–84] and will be used for evaluation of microbicide efficiency in clinical trials.

Even the resolution of all these problems and the development of the most efficient microbicide may not be sufficient. Like therapy in which a combination of antiretrovirals leads to a more efficient treatment of HIV-1, a successful HIV-1 microbicide should contain a combination of drugs targeting different mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission as well as host and viral proteins. Importantly, this strategy will also decrease the chances of the development of drug-resistant HIV-1 forms that may appear if HIV-1-infected individuals who are not aware of their status repeatedly use a microbicide. Efforts in developing such microbicides should remain a priority. Moreover, since microbicides alone are not likely to curb the HIV-1 epidemic, efforts should focus on innovative ideas that maximize the chances of prevention of HIV-1 transmission by combining several HIV-1 prevention strategies [85].

Although it became a common place to claim that more basic knowledge of HIV-1 transmission is needed to develop PrEP in general and microbicides in particular, some of the important problems to be resolved lay outside of the basic science laboratory experiments. These include choosing the right cohort of subjects for a clinical trial and increasing the subjects’ adherence and measurement, as well as better understanding of social and cultural traditions.

Therefore, to advance the microbicide field we need not only basic scientists to acquire more knowledge of the mechanisms of HIV-1 transmission but also the coordinated efforts of physicians, pharmacists, psychologists, and public activists to translate this knowledge into an efficient preventive strategy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NICHD Intramural Program. We are grateful to Dr. Robin Shattock for critical remarks and helpful comments and to Jeremy Swan, Melissa Sisk, and Yumiko Shepherd for their generous assistance in preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, McCauley M, Gamble TR. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):99–105. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834f5cf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorbach PM, et al. Anal intercourse among young heterosexuals in three sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(4):193–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181901ccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalichman SC, et al. Heterosexual anal intercourse among community and clinical settings in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(6):411–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haase AT. Targeting early infection to prevent HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Nature. 2010;464(7286):217–23. doi: 10.1038/nature08757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen R, et al. GP41-specific antibody blocks cell-free HIV type 1 transcytosis through human rectal mucosa and model colonic epithelium. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3648–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Witte L, Nabatov A, Geijtenbeek TB. Distinct roles for DC-SIGN+-dendritic cells and Langerhans cells in HIV-1 transmission. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(1):12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lederman MM, Offord RE, Hartley O. Microbicides and other topical strategies to prevent vaginal transmission of HIV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(5):371–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norvell MK, Benrubi GI, Thompson RJ. Investigation of microtrauma after sexual intercourse. J Reprod Med. 1984;29(4):269–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35(4):565–82. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pudney J, Quayle AJ, Anderson DJ. Immunological microenvironments in the human vagina and cervix: mediators of cellular immunity are concentrated in the cervical transformation zone. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(6):1253–63. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaushic C, et al. Increased prevalence of sexually transmitted viral infections in women: the role of female sex hormones in regulating susceptibility and immune responses. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;88(2):204–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hladik F, Doncel GF. Preventing mucosal HIV transmission with topical microbicides: challenges and opportunities. Antiviral Res. 2010;88(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase AT. Early events in sexual transmission of HIV and SIV and opportunities for interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:127–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-080709-124959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg S, et al. Advances in development, scale-up and manufacturing of microbicide gels, films, and tablets. Antiviral Res. 2010;88(Suppl 1):S19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings R, Clegg A. The inhibitory effect of spermicidal agents on replication of HSV-2 and HIV-1 in-vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32(1):71–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moench TR, et al. The cat/feline immunodeficiency virus model for transmucosal transmission of AIDS: nonoxynol-9 contraceptive jelly blocks transmission by an infected cell inoculum. Aids. 1993;7(6):797–802. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Damme L, et al. Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9338):971–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson L, et al. SAVVY (C31G) gel for prevention of HIV infection in women: a Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Ghana. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldblum PJ, et al. SAVVY vaginal gel (C31G) for prevention of HIV infection: a randomized controlled trial in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2008;3(1):e1474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reina JJ, et al. HIV microbicides: state-of-the-art and new perspectives on the development of entry inhibitors. Future Med Chem. 2010;2(7):1141–59. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGowan I, et al. Phase 1 randomized trial of the vaginal safety and acceptability of SPL7013 gel (VivaGel) in sexually active young women (MTN-004) AIDS. 2011;25(8):1057–64. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328346bd3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscicki AB, et al. Measurement of mucosal biomarkers in a phase 1 trial of intravaginal 3% StarPharma LTD 7013 gel (VivaGel) to assess expanded safety. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(2):134–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823f2aeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsuya H, et al. Dextran sulfate suppression of viruses in the HIV family: inhibition of virion binding to CD4+ cells. Science. 1988;240(4852):646–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2452480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Loughlin J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of SPL7013 gel (VivaGel): a dose ranging, phase I study. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):100–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bc0aac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skoler-Karpoff S, et al. Efficacy of Carraguard for prevention of HIV infection in women in South Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9654):1977–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Damme L, et al. Lack of effectiveness of cellulose sulfate gel for the prevention of vaginal HIV transmission. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):463–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack S, et al. PRO2000 vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection (Microbicides Development Programme 301): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9749):1329–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdool Karim SS, et al. Safety and effectiveness of BufferGel and 0.5% PRO2000 gel for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Aids. 2011;25(7):957–66. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834541d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beer BE, et al. In vitro preclinical testing of nonoxynol-9 as potential anti-human immunodeficiency virus microbicide: a retrospective analysis of results from five laboratories. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(2):713–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.713-723.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merbah M, et al. Cervico-vaginal tissue ex vivo as a model to study early events in HIV-1 infection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(3):268–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrera C, Shattock RJ. Potential use of protease inhibitors as vaginal and colorectal microbicides. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10:42–52. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shattock RJ, Rosenberg Z. Microbicides: Topical Prevention against HIV. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(2):a007385. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdool Karim Q, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celum C, Baeten JM. Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: evolving evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25(1):51–7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834ef5ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Person AK, Hicks CB. Pre-exposure prophylaxis--one more tool for HIV prevention. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10(2):117–22. doi: 10.2174/157016212799937254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson J. Study halted: no benefit seen from antiretroviral pill in preventing HIV in women. JAMA. 2011;305(19):1952. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gengiah TN, et al. A drug evaluation of 1% tenofovir gel and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate tablets for the prevention of HIV infection. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21(5):695–715. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.667072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karim SS, et al. Drug concentrations after topical and oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis: implications for HIV prevention in women. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):279–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60878-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karim SS, Karim QA. Antiretroviral prophylaxis: a defining moment in HIV control. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):e23–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermund SH, Van Damme L. HIV prevention in women: next steps. Science. 2011;331(6015):284. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6015.284-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurt CB, Eron JJ, Jr, Cohen MS. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(12):1265–70. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patton DL, et al. Preclinical safety assessments of UC781 anti-human immunodeficiency virus topical microbicide formulations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(5):1608–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00984-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nel AM, et al. Pharmacokinetic assessment of dapivirine vaginal microbicide gel in healthy, HIV-negative women. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(11):1181–90. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Clercq E. Where rilpivirine meets with tenofovir, the start of a new anti-HIV drug combination era. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Tsai CC, et al. Cyanovirin-N gel as a topical microbicide prevents rectal transmission of SHIV89.6P in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19(7):535–41. doi: 10.1089/088922203322230897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veazey RS, et al. Protection of macaques from vaginal SHIV challenge by vaginally delivered inhibitors of virus-cell fusion. Nature. 2005;438(7064):99–102. doi: 10.1038/nature04055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emau P, et al. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J Med Primatol. 2007;36(4–5):244–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lederman MM, et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in rhesus macaques through inhibition of CCR5. Science. 2004;306(5695):485–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1099288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veazey RS, et al. Protection of rhesus macaques from vaginal infection by vaginally delivered maraviroc, an inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CCR5 co-receptor. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(5):739–44. doi: 10.1086/655661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neff CP, et al. A topical microbicide gel formulation of CCR5 antagonist maraviroc prevents HIV-1 vaginal transmission in humanized RAG-hu mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vangelista L, et al. Engineering of Lactobacillus jensenii to secrete RANTES and a CCR5 antagonist analogue as live HIV-1 blockers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(7):2994–3001. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01492-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagenaur LA, et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in macaques by a live recombinant Lactobacillus. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4(6):648–57. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cates W., Jr After CAPRISA 004: time to re-evaluate the HIV lexicon. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):495–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balzarini J, et al. Differential antiherpesvirus and antiretrovirus effects of the (S) and (R) enantiomers of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: potent and selective in vitro and in vivo antiretrovirus activities of (R)-9-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)-2,6-diaminopurine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(2):332–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz JL, et al. A multi-compartment, single and multiple dose pharmacokinetic study of the vaginal candidate microbicide 1% tenofovir gel. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan DH, et al. No impact of oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on herpes simplex virus shedding in HIV-infected adults. Aids. 2011;25(2):207–10. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328341ddf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andrei G, et al. Topical tenofovir, a microbicide effective against HIV, inhibits herpes simplex virus-2 replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(4):379–89. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mesquita PM, et al. Intravaginal ring delivery of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV and herpes simplex virus infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 doi: 10.1093/jac/dks097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lisco A, et al. Acyclovir is activated into a HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor in herpesvirus-infected human tissues. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4(3):260–70. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanpouille C, Lisco A, Margolis L. Acyclovir: a new use for an old drug. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(6):583–7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833229b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu Y, et al. Acyclovir achieves lower concentration in African HIV-seronegative, HSV-2 seropositive women compared to non-African populations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2777–2779. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06160-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vanpouille C, et al. A new class of dual-targeted antivirals: monophosphorylated acyclovir prodrug derivatives suppress both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and herpes simplex virus type 2. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(4):635–43. doi: 10.1086/650343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins KB, et al. Development of an in vitro organ culture model to study transmission of HIV-1 in the female genital tract. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):475–9. doi: 10.1038/74743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mesquita PM, et al. Disruption of tight junctions by cellulose sulfate facilitates HIV infection: model of microbicide safety. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(4):599–608. doi: 10.1086/600867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arien KK, Kyongo JK, Vanham G. Ex vivo models of HIV sexual transmission and microbicide development. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10(1):73–8. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shattock RJ, Griffin GE, Gorodeski GI. In vitro models of mucosal HIV transmission. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):607–8. doi: 10.1038/76138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cummins JE, Jr, et al. Preclinical testing of candidate topical microbicides for anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity and tissue toxicity in a human cervical explant culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(5):1770–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01129-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saba E, et al. HIV-1 sexual transmission: early events of HIV-1 infection of human cervico-vaginal tissue in an optimized ex vivo model. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3(3):280–90. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Southern PJ, et al. Coming of age: reconstruction of heterosexual HIV-1 transmission in human ex vivo organ culture systems. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4(4):383–96. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lisco A, Vanpouille C, Margolis L. Coinfecting viruses as determinants of HIV disease. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6(1):5–12. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson DJ, Pudney J, Schust DJ. Caveats associated with the use of human cervical tissue for HIV and microbicide research. AIDS. 2010;24(1):1–4. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333acfb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lisco A, et al. Semen of HIV-1-infected individuals: local shedding of herpesviruses and reprogrammed cytokine network. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(1):97–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neurath AR, Strick N, Li YY. Role of seminal plasma in the anti-HIV-1 activity of candidate microbicides. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patel S, et al. Seminal plasma reduces the effectiveness of topical polyanionic microbicides. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(9):1394–402. doi: 10.1086/522606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herold BC, et al. Female genital tract secretions and semen impact the development of microbicides for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(3):325–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fichorova RN, et al. Novel vaginal microflora colonization model providing new insight into microbicide mechanism of action. MBio. 2011;2(6):e00168–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00168-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Balzarini J, Schols D. Combination of antiretroviral drugs as microbicides. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10(1):53–60. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Denton PW, et al. One percent tenofovir applied topically to humanized BLT mice and used according to the CAPRISA 004 experimental design demonstrates partial protection from vaginal HIV infection, validating the BLT model for evaluation of new microbicide candidates. J Virol. 2011;85(15):7582–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00537-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Veazey RS, et al. Animal models for microbicide studies. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10(1):79–87. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keele BF, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(21):7552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valley-Omar Z, et al. CAPRISA 004 Tenofovir Microbicide Trial: No Impact of Tenofovir Gel on the HIV Transmission Bottleneck. J Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Keller MJ, et al. PRO 2000 elicits a decline in genital tract immune mediators without compromising intrinsic antimicrobial activity. Aids. 2007;21(4):467–76. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328013d9b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bollen LJ, et al. No increase in cervicovaginal proinflammatory cytokines after Carraguard use in a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(2):253–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815d2f12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shattock RJ, et al. AIDS. Turning the tide against HIV. Science. 2011;333(6038):42–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1206399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]