Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women and child maltreatment (CM) have been traditionally addressed in isolation by researchers, policy makers and programs. In recent years, however, a growing body of research suggests that these types of violence often occur within the same household and that exposure to violence in childhood—either as a victim of physical or sexual abuse or as a witness to IPV—may increase the risk of experiencing or perpetrating different forms of violence later in life.1–4 Moreover, physical punishment of children is more common in households where women are abused and interventions that address child maltreatment may be less effective in households experiencing IPV.1–6

This evidence calls for greater recognition of the intersections between types of violence. We outline 4 specific gaps and present an integrated framework for moving the field forward with respect to the intersection of IPV and CM.

1. NEED FOR CLARITY ABOUT WHAT CONSTITUTES CM AND IPV

Researchers disagree on how to define CM and IPV. Regarding definitions of CM, it is unclear if they should include behaviorally specific acts, the perpetrator’s intent, the actual experience of harm and what types of corporate punishments should be considered CM.7 Another question is when and how definitions of CM and IPV should include emotional abuse. Researchers often limit the definition of IPV to physical acts. However, evidence suggests that stressful household environments – such as those plagued by marital conflict and emotional intimate partner abuse – have serious harmful effects on children’s overall development. Unfortunately, defining and measuring “emotional abuse” pose serious challenges to researchers.9

2. NEED TO CLARIFY WHAT WE MEAN BY “INTERSECTION”

The intersection of CM and IPV takes many forms. Co-occurrence can be loosely defined as IPV and CM taking place during the same time period within a single family. However, there are questions about the degree to which definitions of co-occurrence should include awareness of co-occurrence by different family members, the definition of family, the definition of the time frame, and the most appropriate unit of analysis (e.g. the family, the child, the adult woman).

Even without specific co-occurrence, there are at least 4 other ways in which IPV and CM may intersect. First, they may have similar short- and long-term physical, emotional, and socio-occupational consequences. Second, one type of violence may be a risk factor for the other. Third, IPV and CM may share risk factors and causal mechanisms. Fourth, some prevention and response strategies may be effective for both.

3. NEED TO CONSIDER OTHER TYPES OF VIOLENCE THAT MAY ALSO CO-OCCUR WITH IPV AND CM

Researchers have persuasively argued that there is a need to consider multiple forms of childhood victimization (“poly-victimization”), including assaults, bullying and sexual victimization outside the family, CM by parents or caregivers, property victimization, and witnessing violence.10–13 Research shows that two-thirds of children who experienced any type of violence in the previous year had experienced 2 or more types, which further underscores that addressing the relationship between IPV and CM is an important start, but we should expand our focus to examine other forms of victimization as well.10,12

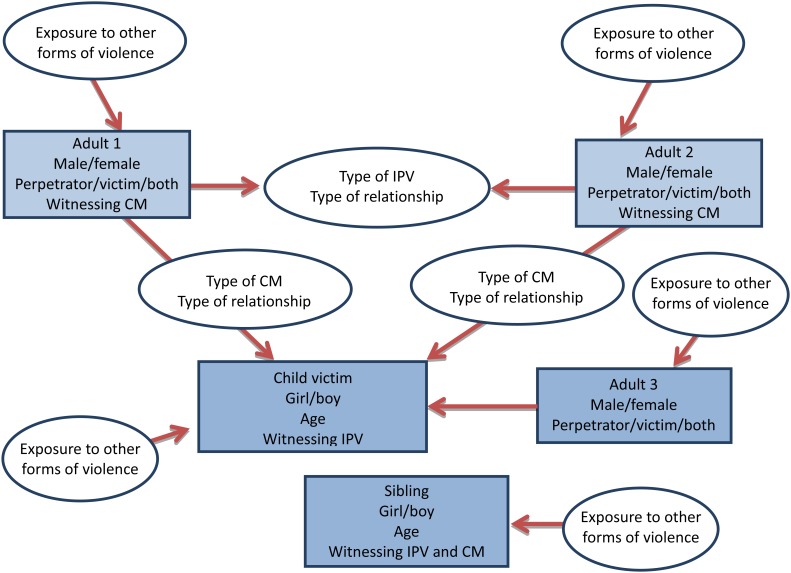

As the framework proposed in the figure shows, addressing poly-victimization and multiple forms of intersections may be complex but has the potential to produce a more complete range of the prevalence of an individual’s total exposure to violence.

4. NEED TO ADDRESS THE GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE ABOUT HOW TO IMPROVE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE TO IPV AND CM

As we move towards greater integration of research, policy and programs addressing IPV and CM, the following important gaps in knowledge should be addressed.

a). The prevalence of different patterns of co-occurrence of CM and IPV

In measuring the prevalence of co-occurrence, 3 denominators are typically used – prevalence of co-occurrence in the general population, prevalence of CM in families in which IPV occurs, and prevalence of IPV in families in which CM occurs, each leading to quite different measures of prevalence. For example, in the United States, the lifetime prevalence of co-occurrence of IPV and CM in the general population is 6%, and the prevalence of CM in families in which IPV occurs is 45%, but these may vary across countries.14–18

b). Consequences of co-occurrence

Literature is scarce on the consequences of co-occurrence of IPV and CM for the child victim and few studies have examined the long-term consequences specifically of co-occurrence to adult victims. A key question is whether children who experience CM and exposure to IPV will suffer worse outcomes than those with fewer forms of victimizations by violent exposures.18–22

c). Risk and protective factors

Risk factors specific to the co-occurrence of CM and IPV are not well understood, and less is known regarding protective factors and resilience in the aftermath of such co-occurrence. Several theories have informed this area, including social cognitive, developmental-ecological, personality disorder, and family systems theories leading to hypotheses about aggressive individuals and family stress.14,16,17 However, the process of understanding the interplay of risk and protective factors associated with the co-occurrence of CM and IPV is still only in its very early stages.

d). Strategies to prevent and mitigate consequences

The evidence regarding effective strategies that expressly target the co-occurrence of IPV and CM remains scarce. The presence of IPV can make CM prevention less effective.6 However, CM can be successfully addressed in the context of IPV.23,24 Unfortunately, few rigorously evaluated programs have specifically targeted the co-occurrence of IPV and CM.

e). Intersections in the case of non-co-occurrence

With regards to the intersections of IPV and CM without co-occurrence, the evidence is limited. Few studies have systematically compared the similarities and differences in the nature and severity of consequences of IPV and CM, for example. CM may be a risk factor for IPV later in life, but few studies have systematically compared the risk factors for CM and IPV and their relative strengths of association.

It is imperative that we address CM and IPV with a new and integrated framework that addresses the needs and gaps outlined above. This is a particularly important issue for moving these fields forward and for providing better prevention interventions, medical care and services to victims of violence. It is also of particular importance that these issues are addressed for the benefit of international comparisons and collaborations. As such, we urge our fellow researchers to work with us to address these important issues.

Figure.

Possible patterns of co-occurrence of intimate partner violence (IPV) and child maltreatment (CM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors are staff members of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions or policies of the World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bott S, Guedes A, Goodwin M, et al. Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109–125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gómez AM, Speizer IS. Intersections between childhood abuse and adult intimate partner violence among Ecuadorian women. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(4):559–566. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0387-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speizer IS, Goodwin M, Whittle L, et al. Dimensions of child sexual abuse before age 15 in three Central American countries: Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(4):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Øverlien C. Children exposed to domestic violence: Conclusions from the literature and challenges ahead. J Soc Work. 2010;10(1):80–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckenrode J, Ganzel B, Henderson CR. Preventing child abuse and neglect with a program of nurse home visitation - The limiting effects of domestic violence. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1385–1391. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, et al., editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3. 2005. Available at: http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

- 9.Jewkes R. Emotional abuse: a neglected dimension of partner violence. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):851–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelhor D. Childhood victimization: violence, crime, and abuse in the lives of young people. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelhor D, Orrarod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, et al. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, et al. The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(10):734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: a review and appraisal. J Fam Psychol. 1998;12(4):578–599. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edleson J. Violence against women and children, vol 1, mapping the terrain, vol 2, navigating solutions. Sex Roles. 2012;67(3–4):251–252. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Slep AMS, et al. Child abuse in the context of domestic violence: prevalence, explanations, and practice implications. Violence and Vict. 2008;23(2):221–235. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knickerbocker L, Heyman RE, Slep AMS, et al. Co-occurrence of child and partner maltreatment - definitions, prevalence, theory, and implications for assessment. European Psychologist. 2007;12(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan KL. Co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child abuse in Hong Kong Chinese families. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(7):1322–1342. doi: 10.1177/0886260510369136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes HM, Parkinson D, Vargo M. Witnessing spouse abuse and experiencing physical abuse: A “double whammy”. J Fam Violence. 1989;4:1471–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCloskey LA, Fernandezesquer ME, Southwick K, et al. The psychological effects of political and domestic violence on Central-American and Mexican immigrant mothers and children. J Community Psychol. 1995;23(2):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sousa C, Herrenkohl TI, Moylan CA, et al. Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(1):111–136. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, et al. The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. J Fam Violence. 2010;25(1):53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Spiller L, et al. Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):774–785. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Skopp NA. Reducing conduct problems among children brought to women’s shelters: Intervention effects 24 months following termination of services. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(1):127–136. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]