Abstract

A series of microPET imaging studies were conducted in anesthetized rhesus monkeys using the dopamine D2-selective partial agonist, [11C]SV-III-130. There was a high uptake in regions of brain known to express a high density of D2 receptors under baseline conditions. Rapid displacement in the caudate and putamen, but not in the cerebellum, was observed after injection of the dopamine D2/3 receptor nonselective ligand S(−)-eticlopride at a low dosage (0.025 mg/kg/i.v.); no obvious displacement in the caudate, putamen and cerebellum was observed after the treatment with a dopamine D3 receptor selective ligand WC-34 (0.1 mg/kg/i.v.). Pretreatment with lorazepam (1 mg/kg, i.v. 30 min) to reduce endogenous dopamine prior to tracer injection resulted in unchanged binding potential (BP) values, a measure of D2 receptor binding in vivo, in the caudate and putamen. D-amphetamine challenge studies indicate that there is a significant displacement of [11C]SV-III-130 by d-amphetamine-induced increases in synaptic dopamine levels.

Keywords: Dopamine, Dopamine D2 receptors, Positron Emission Tomography

INTRODUCTION

Based on genetic and pharmacological studies, dopamine receptors are classified as the D1-like (D1 and D5 receptor subtypes) and the D2-like (D2, D3 and D4 receptor subtypes). Agonist stimulation of D1-like receptors activate adenylyl cyclase via coupling to the Galpha(S)/Galpha(olf) class of G proteins (Herve et al., 2001). Stimulation of the D2-like receptors leads to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity via coupling with the Gi/Go class of G proteins (Sibley and Monsma, 1992, Sealfon and Olanow, 2000, Vallone et al., 2000). Dopamine receptor subtypes regulate dopaminergic circuits in a variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and schizophrenia (Lee et al., 1978, Missale et al., 1998, Jardemark et al., 2002, Nieoullon, 2002, Kapur and Mamo, 2003, Korczyn, 2003, Luedtke and Mach, 2003, Karimi et al., 2011). In addition, activation of the dopaminergic pathways may mediate the reinforcing effects of pyschostimulants, including cocaine and amphetamines (Uhl et al., 1998, Nader et al., 1999, Volkow et al., 2002). Dopamine receptors were also involved in the sleep deprivation-induced remodeling of dopamine circuits (Lim et al., 2011).

Positron emission tomography (PET) is an in vivo imaging technique which is capable of providing measures of receptor density in the living human brain. To date numerous PET imaging studies have been reported using carbon-11 and fluorine-18 labeled radiotracers such as [11C]raclopride, [11C]fallypride, [18F]fallypride, and [11C]FLB 457 (Yokoi et al., 2002, Buchsbaum et al., 2006, Cselenyi et al., 2006, Volkow et al., 2008, Narendran et al., 2009, Vandehey et al., 2010). However, these radiotracers are nonselective antagonists at both D2 and D3 receptors; consequently, the measure of dopamine receptor density, commonly referred to as the “binding potential”, is typically reported as the D2/3 receptor binding potential. A number of 11C-labeled D2-agonists have been reported in recent years. Examples include [11C](+)-PHNO (Ginovart et al., 2006, Narendran et al., 2006), [11C]NPA (Hwang et al., 2000, Narendran et al., 2004), and [11C]MNPA (Finnema et al., 2005, Seneca et al., 2006, Finnema et al., 2009). However, as with the radiolabeled antagonists described above, the binding potentials from PET studies with these radiotracers consist of a composite of the D3 receptor and high affinity state of the D2 receptor (highD2).

In previous efforts, our group structurally modified NGB 2904 to yield the compounds WC-10 and LS-3-134, which have high D3 affinity, good D3 vs. D2 receptor selectivity, and favorable log P value to serve as radiotracers for in vitro and in vivo imaging studies of the D3 receptor (Mach et al., 2011). WC-10 has also been labeled with tritium, and [3H]WC-10 has proven to be a useful radioligand for in vitro autoradiography studies in rodent and nonhuman primate brain (Xu et al., 2009, Xu et al., 2010, Brown et al., 2011, Lim et al., 2011). We have also reported PET imaging studies of dopamine D3 receptors using [18F]LS-3-134 (Mach et al., 2011), which can reproducibly image dopamine D3 receptors in anesthetized nonhuman primates following the administration of the benzodiazepine agonist, lorazepam, to transiently reduce synaptic dopamine levels (Dewey et al., 1992, Nader et al., 2006).

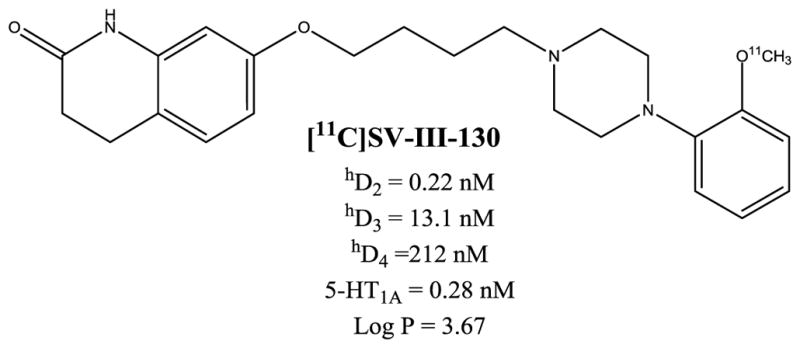

In a similar manner, structural alteration of Aripiprazole (Abilify™), an atypical antipsychotic for treatment of schizophrenia, yielded the analog 7-(4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)butoxy)-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one oxalate (SV-III-130). SV-III-130 has improved D2 versus D3 receptor selectivity in comparison with Aripirazole, a methoxy group for carbon-11 radiolabeling, and a favorable log P to serve as a radiotracer for PET imaging studies of the D2 receptor (Vangveravong et al., 2011). In this study, we report the synthesis of [11C]SV-III-130, a radiolabeled D2 partial agonist that is capable of imaging the dopamine D2 receptor in vivo with positron emission tomography. We also report evidence suggesting that there is a low level of competition between [11C]SV-III-130 and endogenous dopamine for D2 receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Radiosynthesis

The synthesis of the des-methyl precursor, SV-III-158, and unlabeled SV-III-130 (HPLC standard) was reported previously by our group (Vangveravong et al., 2011). [11C]SV-III-130 was prepared via O-alkylation of SV-III-158 with [11C]methyl iodide. The final product was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (C-18 column; 52% methanol: 48% ammonium formate buffer).

Receptor Binding Assays

In vitro binding assays for human dopamine receptors were conducted using the assay conditions described by Chu et al. in 2005. The radioligand used in the dopamine receptor binding assay was [125I]IABN, which has a high affinity for dopamine D2, D3 and D4 receptors (Luedtke et al., 2000). To measure the binding affinity at 5-HT1A receptors, a filtration binding assay previously described (Xu et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2011) was used with human 5-HT1A serotonin receptor membranes (ChanTest, Cleveland, OH, U.S.) and [3H] 8-OH-DPAT (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA, U.S.) as the radioligand.

Intrinsic Activity Assay

The intrinsic activity at dopamine D2 receptors was determined using the cAMP assay conditions as described in 2005 by Chu et al. (Chu et al., 2005). In this assay, quinpirole was used as a reference full agonist at both D2 and D3 dopamine receptors.

PET Data acquisition

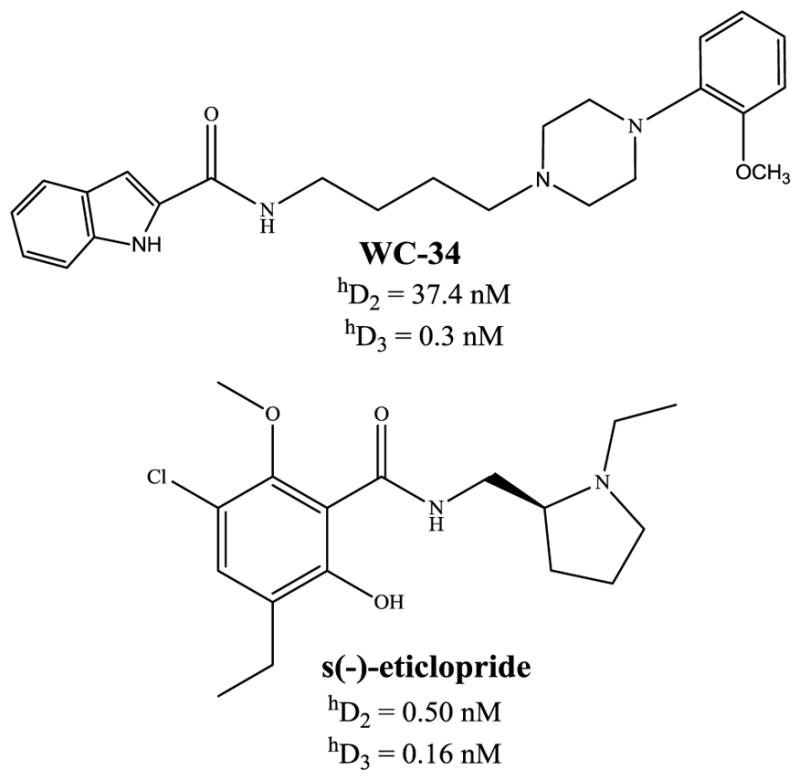

MicroPET imaging studies were conducted on a Focus 220 microPET scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA). Male rhesus monkeys (8 – 12 kg) were initially anesthetized with ketamine (10–15 mg/kg) and injected with glycopyrrolate (0.013 – 0.017 mg/kg) to reduce saliva secretions. PET tracers were administered ~ 90 minutes after ketamine injection. Subjects were intubated and placed on the scanner bed with a circulating warm water blanket and blankets. A water-soluble ophthalmic ointment was placed in the eyes, and the head was positioned in the center of the field using gauze rolls taped in place. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (1.0 – 1.75 % in 1.5 L/min oxygen flow). Respiration rate, pulse, oxygen saturation, body temperature, and inspired/exhaled gasses were monitored throughout the study. Radiotracers and fluids were administered using a catheter placed percutaneously in a peripheral vein. For the metabolism studies, a catheter was placed percutaneously in the contralateral femoral artery to permit the collection of arterial blood samples and for the determination of the blood time-activity-curve using a continuous flow detection system (Hutchins et al., 1986). In each microPET scanning session, the head was positioned supine with the brain in the center of the field of view. A 10-minute transmission scan was performed to check positioning; once confirmed, a 45 minute transmission scan was obtained for attenuation correction. Subsequently, a 60-minute baseline dynamic emission scan was acquired after administration of ~10 mCi of [11C]SV-III-130 via the venous catheter. Displacement studies were also conducted in animals by administering compound S-(−)-eticlopride (0.025 mg/kg, i.v.), a nonselective dopamine D2 and D3 receptor ligand (Nader et al., 1999); and WC-34, a selective dopamine D3 receptor ligand (Chu et al., 2005, Mach et al., 2011), 20 min post tracer injection. Chemical structures of s-(−)-eticlopride and WC-34 and their binding affinities at dopamine receptors are shown in Figure 4. For the dopamine depletion studies, animals were given an intravenous dose of lorazepam (1 mg/kg in saline) approximately 30 min prior to injection of the radiotracer. For dopamine challenge studies, 1 mg/kg d-amphetamine was administrated via the venous catheter 20 min post radiotracer injection.

Figure 4.

Structures and pharmacology of a nonselective dopamine D2/3 receptor ligand s(−)-eticlopride and a selective dopamine D3 receptor ligand WC-34. A summary of binding affinities (dissociation constants) for human dopamine D2 and D3 receptors are shown. Pharmacological data are taken from Chu et al., 2005 and Nader et al., 1999.

Time Activity Curves and Metabolite analysis

Arterial blood time activity curves for the initial 5 min post [11C]SV-III-130 injection were determined using the continuous flow detection system attached to a percutaneous arterial catheter. Arterial blood samples for metabolite analysis were taken in a heparinized syringe from the same catheter at 5 and 30 min post injection. The 5 min sample was taken immediately after the pump for the detector was turned off; the arterial line was flushed prior to collection of subsequent samples. Additional blood samples were taken at 10, 60 min for the TAC (Figure 5 C). Metabolite analysis was performed using a solid-phase extraction technique previously used for similar studies (Mach et al., 1997). A 1 mL aliquot of whole blood was centrifuged to separate plasma from packed red cells. Each fraction was counted, a 400 μL aliquot of plasma was removed, counted and deproteinated with 6 ml of 2: 1 methanol: 0.4 M perchloric acid mixture. After centrifugation the supernatant was diluted with 4 mL water and applied to an activated C-18 light Sep-Pak. The cartridge was neutralized with 2 mL 1N NaOH, then rinsed twice with water, and extracted with two portions of methanol (2 mL, 1 mL). All samples were counted in a Ludlum well counter. The methanol extracts were combined, concentrated in vacuo and rediluted to 150 μL of methanol for injection onto the HPLC. HPLC analysis was performed using a reversed-phase Phenomenex analytical column (Prodigy 250 × 4.6) with a mobile phase of methanol: 0.1 M ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.5 60:40. The flow rate was 0.8 ml/min, 0.5 min/fraction; 36 fractions were collected and counted or each sample. The location of the parent UV peak was determined by injection of cold standard. After HPLC analysis of all plasma samples had been completed, the purity and stability of the injectate were confirmed by analysis of both reserved injectate and an in vitro control (reserved injectate added to a pre-scan blood sample which was immediately processed as described above). This control also confirmed the stability of the radiotracer under the conditions used to process the blood for metabolite analysis. The percentages of unchanged parent compound and its metabolites were determined by decay correcting the counts and dividing the amount of recovered activity in all samples and multiplying by 100. (Table 2) Only a single peak for the parent compound was observed in the in vitro control and > 95% of the activity was recovered.

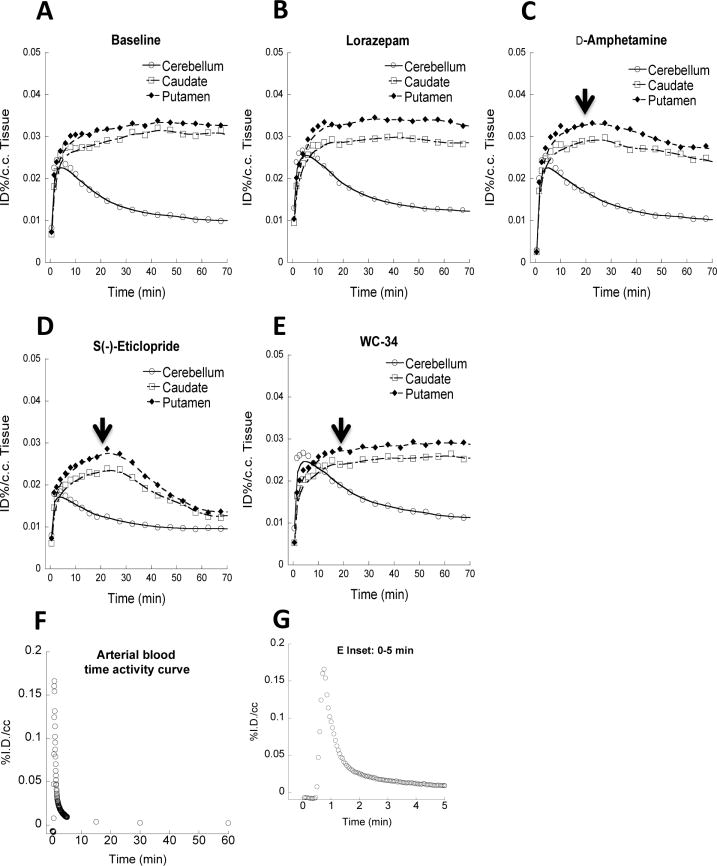

Figure 5.

Representative blood and Tissue time-activity curves (TACs) of [11C]SV-III-130 from microPET imaging studies. A and B show regional brain TACs from baseline and lorazepam studies. The uptake of [11C]SV-III-130 in the representative monkey brain regions (caudate, putamen and cerebellum) reached peak accumulation in the caudate and putamen 10 min post-i.v. injection. Lorazepam (1 mg/kg/i.v.) treatment didn’t increase [11C]SV-III-130 uptake in the caudate and putamen. C shows that 1 mg/kg d-amphetamine challenge slightly decreased [11C]SV-III-130 uptake in the caudate and putamen. Arrow shows the time point (20 min) when d-amphetamine was administrated. D shows that [11C]SV-III-130 uptake in the caudate and putamen was reversible, 0.025 mg/kg/i.v. s(−)-eticlopride rapidly displaced [11C]SV-III-130 binding to dopamine D2 receptors in the caudate and putamen. E shows that [11C]SV-III-130 uptake in the caudate and putamen was specific to dopamine D2 receptors, which was not displaced by 0.1 mg/kg/i.v. WC-34, a dopamine D3 receptor selective ligand. F shows the arterial blood TAC. The inset graph G shows the TAC of the initial 5 minutes.

Table 2.

Percent parent compound [11C]SV-III-130 in arterial blood samples of rhesus monkey

| Time (min) | % Parent Compound |

|---|---|

| 5 | 76.3 ± 1.7 |

| 30 | 60.6 ± 5.8 |

Image processing and analysis

Acquired list mode data were histogrammed into a 3D set of sinograms and binned to the following time frames: 3 × 1 min, 4 ×2 min, 3 ×3 min and 20 ×5 min. Sinogram data were corrected for attenuation and scatter. Maximum a posteriori (MAP) reconstructions were done with 18 iterations and a beta value of 0.004, resulting in a final 256 ×256 ×95 matrix. The voxel dimensions of the reconstructed images were 0.95 ×0.95 ×0.80 mm3. A 1.5 mm Gaussian filter was applied to smooth each MAP reconstructed image. These images were then co-registered with MRI images to identify the regions of interest with AnalyzeDirect software (AnalyzeDirect, Inc., Overland Park, KS). 3D regions of interest PET images were manually drawn using co-registered MRI images as references for the caudate, putamen and cerebellum to obtain time–activity curves. Activity measures were standardized to dose of radioactivity injected to yield %ID/c.c. (Figure 5 A and B.). Logan DVR-1 (binding potential) analyses were performed using the cerebellum as the reference region, with a K2 value of 0.035 (Logan, 2000). Percent dopamine (DA) occupancy (OCC) in the caudate and putamen was measured as (1−[DVRbaseline −1]/[DVRd-amphetamine −1])×100 (Mukherjee et al., 2001).

RESULTS

In vitro binding studies indicate that SV-III-130 (Figure 1) has a high affinity for D2 receptors (0.22 nM) and ~60-fold selectivity for D2 versus D3 receptors (Table 1). Functional assays demonstrated that SV-III-130 partially inhibited forskolin-dependent adenylyl cyclase activity relative to quinpirole (~ 61% maximal response) in CHO cells transfected with hD2 receptors (Table 1), indicating that it is a partial agonist at D2 receptors. The affinity of SV-III-130 for dopamine D4 receptors was low (~210 nM). It’s noteworthy that SV-III-130 also has high binding affinity for 5-HT1A receptor (0.28 nM).

Figure 1.

Structure and pharmacology of D2-selective ligand SV-III-130. A summary of SV-III-130’s binding affinity (dissociation constants) for human dopamine D2, D3, D4 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors are shown. The theoretical values for the partition coefficient, log P, was obtained using ChemDraw. Pharmacological data for dopamine receptors are taken from Vangveravong et al., 2011.

Table 1.

| D2long | D3 | D4 | D2:D3 Ratio | %IA D2 | %IA D3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.22 ± 0.01 nM | 13.1 ± 2.3 nM | 212 ± 45 nM | 60 | 61.2 ± 4.4 | 52.5 ± 4.4 |

Ki values (nM) were determined using human receptors expressed in HEK cells with 125I-IABN. The Ki values represent the mean values for n > 3 determinations.

Percent intrinsic activity (%IA) at human D2 or D3 receptors was determined using a forskolin-dependent adenylyl cyclase whole cell assay at a concentration of test compound >10 × Ki value. The mean values (n > 3) were normalized to values obtained using the full agonist quinpirole.

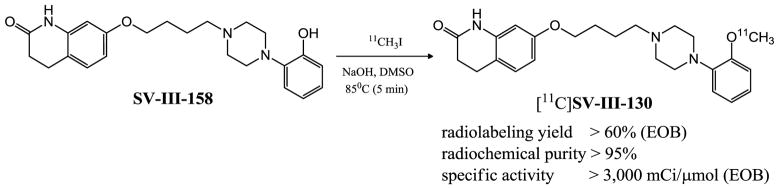

The synthesis of [11C]SV-III-130 was achieved in approximately 60 min in an overall radiochemical yield of 60% from starting [11C]methyl iodide. The specific activity of the final compound was ~3,000 mCi/μmol (end of bombardment); radiochemical purity was greater than 95% and suitable for microPET imaging studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]SV-III-130.

Metabolism studies of arterial blood samples indicated that [11C]SV-III-130 is relatively stable; the 30 minute blood sample post-i.v. administration of the radiotracer contained greater than 60% parent compound (Table 2).

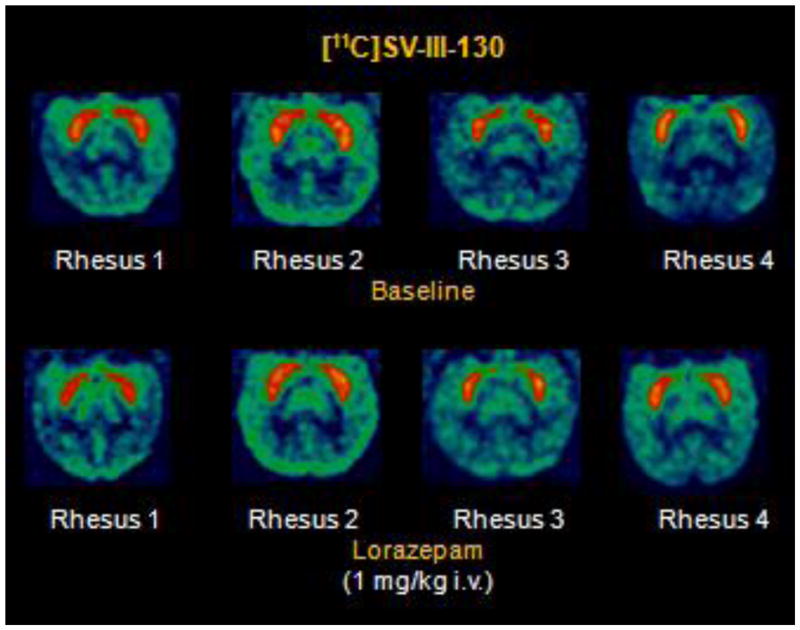

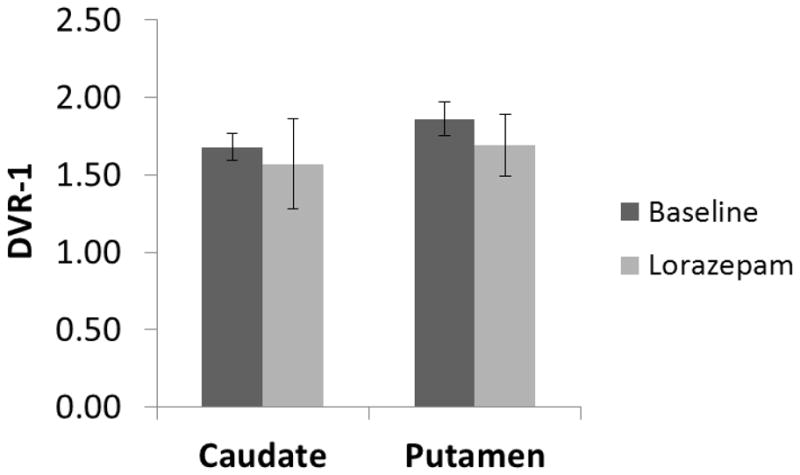

MicroPET studies were conducted in rhesus monkeys under 1% isoflurane anesthesia (n = 4). These initial baseline microPET imaging studies (Figure 3, top panel) demonstrated high uptake of [11C]SV-III-130 in the caudate and putamen. A second series of studies were conducted in which the animal received an intravenous dose of lorazepam (1.0 mg/kg) 30 min prior to the injection of the radiotracer (Figure 3, bottom panel). Lorazepam has been shown to increase striatal [11C]raclopride binding (Dewey et al., 1992); we previously used this paradigm to evaluate the effect of endogenous dopamine on the binding of the dopamine D2/3 radiotracer, [18F]FCP, and the dopamine D3 radiotracer [18F]LS-3-134 in rhesus monkeys (Nader et al., 2006, Mach et al., 2011). The tissue-time activity curves in the lorazepam-treated animals were similar to the baseline study (Figure 5 A and B). Pretreatment with lorazepam had no significant effects on the binding of [11C]SV-III-130 to dopamine D2 receptors as measured by the Logan DVR-1 analyses (Figure 6) (Logan, 2000). There was no obvious binding of [11C]SV-III-130 in the thalamus, a region known to express D3 versus D2 receptors (Rabiner et al., 2009, Sun et al., 2012) under either baseline and lorazemap depletion conditions. This data indicate that [11C]SV-III-130 does not label dopamine D3 receptors in vivo. In contrast to the depletion of endogenous dopamine with lorazepam, dopamine challenge studies resulting from the administration of d-amphetamine (1 mg/kg/i.v.) 20 minutes post-i.v. injection of the radiotracer resulted in a displacement of [11C]SV-III-130 in the caudate and putamen (Figure 5 C). Binding potential analyses demonstrated that the effect of d-amphetamine is significant for both caudate (p = 0.0001) and putamen (p = 0.03) (Table 3). Percent dopamine (DA) occupancy (OCC) is higher in the caudate than in the putamen for all 4 monkeys. Rapid displacement in the caudate and putamen, but not in the cerebellum, was observed after injection of the dopamine D2/3 nonselective ligand S(−)-eticlopride at a relatively low dosage (0.025 mg/kg/i.v.) (Figure 5 D). These data indicate that the binding of [11C]SV-III-130 to D2 receptors in the caudate and putamen is reversible. A dopamine D3 receptor selective ligand WC-34 (0.025 mg/kg/i.v.) didn’t displace the binding of [11C]SV-III-130 in the caudate and putamen, which suggests that the binding of [11C]SV-III-130 is specific to dopamine D2 v.s. D3 receptors. [11C]SV-III-130 activity uptake in the blood peaked at ~ 1 minute post tracer injection and displayed rapid blood activity clearance (Figure 5 F and G).

Figure 3.

MicroPET imaging studies of [11C]SV-III-130 in rhesus monkeys.

Figure 6.

Binding potential (DVR-1) analysis in caudate and putamen of microPET scans from baseline (test-retest average), lorazepam treatment and d-amphetamine challenge studies. Lorazepam has no significant effects on the [11C]SV-III-130 binding potential in the caudate (p = 0.26) and putamen (p = 0.12).

Table 3.

DVR-1 and dopamine occupancy (DA OCC) induced by d-amphetamine in monkey caudate and putamen measured using [11C]SV-III-130.

| Monkeya | Caudate DVR-1 | Putamen DVR-1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselineb | AMPHc | DAd OCC | Baselineb | AMPHc | DAd OCC | |

| Monkey 1 | 1.55 | 1.17 | 25% | 1.70 | 1.45 | 15% |

| Monkey 2 | 1.80 | 1.05 | 42% | 2.00 | 1.73 | 13% |

| Monkey 3 | 1.69 | 1.03 | 39% | 1.85 | 1.22 | 34% |

| Monkey 4 | 1.71 | 1.43 | 16% | 1.89 | 1.76 | 7% |

Four rhesus male monkeys were studied separately;

Baseline DVR-1 values represent test-retest average of at least two studies for each individual monkey;

D-amphetamine (AMPH) (1 mg/kg/i.v.) significantly decreased [11C]SV-III-130 binding potential in striatal regions: caudate (p = 0.001) and putamen (p = 0.03);

Percent dopamine (DA) occupancy (OCC) is higher in the caudate than in the putamen for all 4 monkeys.

DISCUSSION

Despite the structure similarities and high degree of sequence homology in the ligand binding domains (Sokoloff et al., 1990), the D2 and D3 receptors are thought to differ in their a) neuroanatomical localization, b) levels of receptor expression, c) efficacy in response to agonist stimulation, and d) regulation and desensitization (Joyce, 2001, Luedtke and Mach, 2003, Mach et al., 2004). However, the absolute densities of D2 and D3 receptors, and the differential expression of these receptors in the CNS, is currently not known since there are no selective radioligands to measure D2 versus D3 receptors, and vice versa, using either in vitro (autoradiography) or in vivo (PET) imaging techniques. Although a number of dopamine D2 and D3 selective radiotracers, labeled with either carbon-11 (t = 20.4 min) or fluorine-18 (t = 110 min), have been reported over the past twenty years, none have proven to be useful for selectively imaging dopamine D2 or D3 receptors in vivo. Nonselective dopamine D2/D3 radiotracers inevitably provide a binding potential from the combination of both receptor signals, such as the radiolabeled antagonists [11C]raclopride (Yokoi et al., 2002, Volkow et al., 2008), [11C]fallypride or [18F]fallypride (Buchsbaum et al., 2006, Narendran et al., 2009); and [11C]FLB457 (Cselenyi et al., 2006, Vandehey et al., 2010), and full agonists at D2 and D3 receptors, [11C](+)-PHNO (Ginovart et al., 2006, Narendran et al., 2006), [11C]NPA (Hwang et al., 2000, Narendran et al., 2004), and [11C]MNPA (Finnema et al., 2005, Seneca et al., 2006, Finnema et al., 2009).

In a previous study, we reported that [18F]LS-3-134 has a subnanomolar affinity for dopamine D3 receptors and a 160-fold higher affinity for D3 compared to D2 dopamine receptors (Mach et al., 2011). Because of the high affinity of dopamine for D3 receptors, it was necessary to deplete the synapse dopamine of [18F]LS-3-134 in anesthetized rhesus monkeys in order to image the D3 receptor. These data are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that there is a high in vivo occupancy of D3 receptors by endogenous dopamine (Schotte et al., 1992, Schotte et al., 1996). That study also demonstrated that [18F]LS-3-134 had high binding in the thalamus which is believed to be a brain region having a high density of D3 receptors (Rabiner et al., 2009, Sun et al., 2012). In the current study, we found [11C]SV-III-130 had high binding in the caudate and putamen and no uptake in the thalamus. Dopamine depletion did not increase the uptake of the radiotracer in the caudate, putamen and thalamus. These data suggest [11C]SV-III-130 binding to dopamine D3 receptors is negligible since there was no tracer uptake in the thalamus under both baseline and dopamine depletion conditions. Recently it was reported that dopamine D2 receptor preferring ligand [18F](N-Methyl)Benperidol (NMB) has appreciable binding in the thalamus (Eisenstein et al., 2012); this very likely represents binding at dopamine D4 receptors since [18F]NMB has a high binding affinity at the D4 receptor (Ki = 4.9 nM), and there is a high density of D4 receptors in the thalamus (Primus et al., 1997, Karimi et al., 2011). The observation that dopamine depletion did not change the binding potential of [11C]SV-III-130 in the caudate and putamen also suggests that endogenous dopamine has a low in vivo occupancy at D2 receptors. This result agrees well with previous reports that endogenous dopamine protects the D3 receptor (but not the D2) receptors from alkylation by 1-ethoxycarbonyl-2-ethoxy-1,2-dihydroquinoline (EEDQ) and the spiperone analog, N-(p-isothiocyanatophenethyl)spiperone (NIPS) (Levant, 1995, Zhang et al., 1999). Occupancy of D3 receptors by endogenous dopamine in vivo is high due to the higher binding affinity of dopamine for dopamine D3 versus D2 receptors (Levant, 1997).

Unlike the dopamine depletion studies using lorazepam, d-amphetamine challenge given 20 min post-i.v. injection of the radiotracer resulted in a change (i.e., reduction) of [11C]SV-III-130 binding in the caudate and putamen. This reduction in tracer binding is believed to be caused by the in vivo displacement of radiotracer by d-amphetamine-induced elevations in synaptic dopamine levels. A higher percent dopamine (DA) occupancy (OCC) was observed in the caudate than in the putamen, which is consistent with a previous report using [18F]fallypride as the radioligand (Mukherjee et al., 2005). To confirm the displaceable binding of [11C]SV-III-130 to dopamine D2 receptors in the caudate and putamen, a low dose of the D2/3 antagonist S(−)-eticlopride (0.025 mg/kg/i.v.) was administered at 20 min post-i.v. injection of the radiotracer. S(−)-eticlopride rapidly displaced [11C]SV-III-130 binding in the caudate and putamen, with the striatal activity reached a level close to that in the reference region of cerebellum by ~ 50 min post-injection. To test the specificity of [11C]SV-III-130 binding to dopamine D2 but not D3 receptors, a relatively high dose (4 fold higher of that of s(−)-eticlopride, i.e., 0.1 mg/kg/i.v.) of selective D3 receptor partial agonist WC-34 was administered at 20 min post-i.v. injection of the radiotracer, no obvious displacement of [11C]SV-III-130 was observed.

Although the in vitro binding assay showed that SV-III-130 has a high binding affinity for 5-HT1A receptor, the in vivo PET imaging studies didn’t suggest that [11C]SV-III-130 labeled 5-HT1A sites in the nonhuman primate brains; no obvious uptake was detected in the 5-HT1A receptor enriched regions, such as the dorsal raphe, cingulate cortex and hippocampus(Saigal et al., 2006).

In summary, we have evaluated the in vivo properties of [11C]SV-III-130, a radiotracer with subnanomolar affinity for dopamine D2 receptors and 60-fold selectivity over dopamine D3 receptors. Preclinical imaging studies using nonhuman primates indicates [11C]SV-III-130 images dopamine D2 but not D3 receptors. This study also demonstrated that dopamine D2 receptors can be imaged in nonhuman primates without the need to deplete the dopaminergic synapses of endogenous neurotransmitter, which is in stark contrast to the imaging of D3 receptors with the radiotracer [18F]LS-3134. Translational imaging studies in human subjects are clearly needed to determine the ability of [11C]SV-III-130 to directly measure dopamine D2 receptors without interference from the labeling of D3 receptors.

Highlights.

We synthesized a novel dopamine D2 receptor radiotracer, [11C]SV-III-130.

We conducted microPET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors using [11C]SV-III-130.

[11C]SV-III-130 binding can be displaced D2/3 ligand S(−)-eticlopride.

Dopamine depletion via lorazepam treatment didn’t change the binding potential.

D-amphetamine induced dopamine increase displaced [11C]SV-III-130 binding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank John Hood, Christina Zukas and Darryl Craig for their assistance and technical expertise in conducting the nonhuman primate imaging studies. This research was funded by NIH grants MH081281 and DA023957.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brown JA, Xu J, Diggs-Andrews KA, Wozniak DF, Mach RH, Gutmann DH. PET imaging for attention deficit preclinical drug testing in neurofibromatosis-1 mice. Experimental neurology. 2011;232:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Christian BT, Lehrer DS, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mantil J, Kemether E, Oakes TR, Mukherjee J. D2/D3 dopamine receptor binding with [F-18]fallypride in thalamus and cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;85:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu W, Tu Z, McElveen E, Xu J, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Mach RH. Synthesis and in vitro binding of N-phenyl piperazine analogs as potential dopamine D3 receptor ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cselenyi Z, Olsson H, Halldin C, Gulyas B, Farde L. A comparison of recent parametric neuroreceptor mapping approaches based on measurements with the high affinity PET radioligands [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]WAY 100635. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1690–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Smith GS, Logan J, Brodie JD, Yu DW, Ferrieri RA, King PT, MacGregor RR, Martin TP, Wolf AP, et al. GABAergic inhibition of endogenous dopamine release measured in vivo with 11C-raclopride and positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3773–3780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03773.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Koller JM, Piccirillo M, Kim A, Antenor-Dorsey JA, Videen TO, Snyder AZ, Karimi M, Moerlein SM, Black KJ, Perlmutter JS, Hershey T. Characterization of extrastriatal D2 in vivo specific binding of [18F](N-methyl)benperidol using PET. Synapse. 2012;66:770–780. doi: 10.1002/syn.21566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnema SJ, Halldin C, Bang-Andersen B, Gulyas B, Bundgaard C, Wikstrom HV, Farde L. Dopamine D(2/3) receptor occupancy of apomorphine in the nonhuman primate brain--a comparative PET study with [11C]raclopride and [11C]MNPA. Synapse. 2009;63:378–389. doi: 10.1002/syn.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnema SJ, Seneca N, Farde L, Shchukin E, Sovago J, Gulyas B, Wikstrom HV, Innis RB, Neumeyer JL, Halldin C. A preliminary PET evaluation of the new dopamine D2 receptor agonist [11C]MNPA in cynomolgus monkey. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginovart N, Galineau L, Willeit M, Mizrahi R, Bloomfield PM, Seeman P, Houle S, Kapur S, Wilson AA. Binding characteristics and sensitivity to endogenous dopamine of [11C]-(+)-PHNO, a new agonist radiotracer for imaging the high-affinity state of D2 receptors in vivo using positron emission tomography. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1089–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve D, Le Moine C, Corvol JC, Belluscio L, Ledent C, Fienberg AA, Jaber M, Studler JM, Girault JA. Galpha(olf) levels are regulated by receptor usage and control dopamine and adenosine action in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4390–4399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04390.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins GD, Hichwa RD, Koeppe RA. A Continuous Flow Input Function Detector for H2 15O Blood Flow Studies in Positron Emission Tomography. Nuclear Science, IEEE Transactions on. 1986;33:546–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DR, Kegeles LS, Laruelle M. (−)-N-[(11)C]propyl-norapomorphine: a positron-labeled dopamine agonist for PET imaging of D(2) receptors. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:533–539. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardemark K, Wadenberg ML, Grillner P, Svensson TH. Dopamine D3 and D4 receptor antagonists in the treatment of schizophrenia. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN. Dopamine D3 receptor as a therapeutic target for antipsychotic and antiparkinsonian drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90:231–259. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Mamo D. Half a century of antipsychotics and still a central role for dopamine D2 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Moerlein SM, Videen TO, Luedtke RR, Taylor M, Mach RH, Perlmutter JS. Decreased striatal dopamine receptor binding in primary focal dystonia: a D2 or D3 defect? Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2011;26:100–106. doi: 10.1002/mds.23401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczyn AD. Dopaminergic drugs in development for Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 2003;91:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Seeman P, Rajput A, Farley IJ, Hornykiewicz O. Receptor basis for dopaminergic supersensitivity in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1978;273:59–61. doi: 10.1038/273059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B. Differential sensitivity of [3H]7-OH-DPAT-labeled binding sites in rat brain to inactivation by N-ethoxycarbonyl-2-ethoxy-1,2-dihydroquinoline. Brain Res. 1995;698:146–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00879-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B. The D3 dopamine receptor: neurobiology and potential clinical relevance. Pharmacological reviews. 1997;49:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Xu J, Holtzman DM, Mach RH. Sleep deprivation differentially affects dopamine receptor subtypes in mouse striatum. Neuroreport. 2011;22:489–493. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834846a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J. Graphical analysis of PET data applied to reversible and irreversible tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke RR, Freeman RA, Boundy VA, Martin MW, Huang Y, Mach RH. Characterization of (125)I-IABN, a novel azabicyclononane benzamide selective for D2-like dopamine receptors. Synapse. 2000;38:438–449. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001215)38:4<438::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke RR, Mach RH. Progress in developing D3 dopamine receptor ligands as potential therapeutic agents for neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:643–671. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach RH, Huang Y, Freeman RA, Wu L, Vangveravong S, Luedtke RR. Conformationally-flexible benzamide analogues as dopamine D3 and sigma 2 receptor ligands. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach RH, Nader MA, Ehrenkaufer RL, Line SW, Smith CR, Gage HD, Morton TE. Use of positron emission tomography to study the dynamics of psychostimulant-induced dopamine release. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach RH, Tu Z, Xu J, Li S, Jones LA, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Derdeyn CP, Perlmutter JS, Mintun MA. Endogenous dopamine (DA) competes with the binding of a radiolabeled D(3) receptor partial agonist in vivo: a positron emission tomography study. Synapse. 2011;65:724–732. doi: 10.1002/syn.20891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Collins D. Measurement of d-amphetamine-induced effects on the binding of dopamine D-2/D-3 receptor radioligand, 18F-fallypride in extrastriatal brain regions in non-human primates using PET. Brain Res. 2005;1032:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mantil J. Evaluation of dopamine D-2 receptor occupancy by clozapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in vivo in the rodent and nonhuman primate brain using 18F-fallypride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:476–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Green KL, Luedtke RR, Mach RH. The effects of benzamide analogues on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;147:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s002130051154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Morgan D, Gage HD, Nader SH, Calhoun TL, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer R, Mach RH. PET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors during chronic cocaine self-administration in monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1050–1056. doi: 10.1038/nn1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Frankle WG, Mason NS, Rabiner EA, Gunn RN, Searle GE, Vora S, Litschge M, Kendro S, Cooper TB, Mathis CA, Laruelle M. Positron emission tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the human cortex: a comparative evaluation of the high affinity dopamine D2/3 radiotracers [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]fallypride. Synapse. 2009;63:447–461. doi: 10.1002/syn.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Hwang DR, Slifstein M, Talbot PS, Erritzoe D, Huang Y, Cooper TB, Martinez D, Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. In vivo vulnerability to competition by endogenous dopamine: comparison of the D2 receptor agonist radiotracer (−)-N-[11C]propyl-norapomorphine ([11C]NPA) with the D2 receptor antagonist radiotracer [11C]-raclopride. Synapse. 2004;52:188–208. doi: 10.1002/syn.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Slifstein M, Guillin O, Hwang Y, Hwang DR, Scher E, Reeder S, Rabiner E, Laruelle M. Dopamine (D2/3) receptor agonist positron emission tomography radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO is a D3 receptor preferring agonist in vivo. Synapse. 2006;60:485–495. doi: 10.1002/syn.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A. Dopamine and the regulation of cognition and attention. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:53–83. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus RJ, Thurkauf A, Xu J, Yevich E, McInerney S, Shaw K, Tallman JF, Gallagher DW. II. Localization and characterization of dopamine D4 binding sites in rat and human brain by use of the novel, D4 receptor-selective ligand [3H]NGD 94-1. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1997;282:1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner EA, Slifstein M, Nobrega J, Plisson C, Huiban M, Raymond R, Diwan M, Wilson AA, McCormick P, Gentile G, Gunn RN, Laruelle MA. In vivo quantification of regional dopamine-D3 receptor binding potential of (+)-PHNO: Studies in non-human primates and transgenic mice. Synapse. 2009;63:782–793. doi: 10.1002/syn.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigal N, Pichika R, Easwaramoorthy B, Collins D, Christian BT, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Potkin SG, Mukherjee J. Synthesis and biologic evaluation of a novel serotonin 5-HT1A receptor radioligand, 18F-labeled mefway, in rodents and imaging by PET in a nonhuman primate. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47:1697–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte A, Janssen P, Bonaventure P, Leysen J. Endogenous dopamine limits the binding of antipsychotic drugs to D3 receptors in the rat brain: a quantitative autoradiographic study. The Histochemical Journal. 1996;28:791–799. doi: 10.1007/BF02272152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, Luyten WH, Leysen JE. Autoradiographic evidence for the occlusion of rat brain dopamine D3 receptors in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;218:373–375. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90196-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealfon SC, Olanow CW. Dopamine receptors: from structure to behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:S34–40. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneca N, Finnema SJ, Farde L, Gulyas B, Wikstrom HV, Halldin C, Innis RB. Effect of amphetamine on dopamine D2 receptor binding in nonhuman primate brain: a comparison of the agonist radioligand [11C]MNPA and antagonist [11C]raclopride. Synapse. 2006;59:260–269. doi: 10.1002/syn.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley DR, Monsma FJ., Jr Molecular biology of dopamine receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu J, Cairns NJ, Perlmutter JS, Mach RH. Dopamine D(1), D(2), D(3) Receptors, Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Type-2 (VMAT2) and Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Densities in Aged Human Brain. PloS one. 2012;7:e49483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Vandenbergh DJ, Rodriguez LA, Miner L, Takahashi N. Dopaminergic genes and substance abuse. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:1024–1032. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60922-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallone D, Picetti R, Borrelli E. Structure and function of dopamine receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandehey NT, Moirano JM, Converse AK, Holden JE, Mukherjee J, Murali D, Nickles RJ, Davidson RJ, Schneider ML, Christian BT. High-affinity dopamine D2/D3 PET radioligands 18F-fallypride and 11C-FLB457: a comparison of kinetics in extrastriatal regions using a multiple-injection protocol. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:994–1007. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangveravong S, Zhang Z, Taylor M, Bearden M, Xu J, Cui J, Wang W, Luedtke RR, Mach RH. Synthesis and characterization of selective dopamine D(2) receptor ligands using aripiprazole as the lead compound. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:3502–3511. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. Role of dopamine in drug reinforcement and addiction in humans: results from imaging studies. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:355–366. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Wong C, Ma J, Pradhan K, Tomasi D, Thanos PK, Ferre S, Jayne M. Sleep deprivation decreases binding of [11C]raclopride to dopamine D2/D3 receptors in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8454–8461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Cui J, Lu X, Padakanti PK, Xu J, Parsons SM, Luedtke RR, Rath NP, Tu Z. Synthesis and in vitro biological evaluation of carbonyl group-containing analogues for sigma1 receptors. J Med Chem. 2011;54:5362–5372. doi: 10.1021/jm200203f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Chu W, Tu Z, Jones LA, Luedtke RR, Perlmutter JS, Mintun MA, Mach RH. [(3)H]4-(Dimethylamino)-N-[4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin- 1-yl)butyl]benzamide, a selective radioligand for dopamine D(3) receptors. I. In vitro characterization. Synapse. 2009;63:717–728. doi: 10.1002/syn.20652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Hassanzadeh B, Chu W, Tu Z, Jones LA, Luedtke RR, Perlmutter JS, Mintun MA, Mach RH. [3H]4-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl) butyl)benzamide: a selective radioligand for dopamine D3 receptors. II. Quantitative analysis of dopamine D3 and D2 receptor density ratio in the caudate-putamen. Synapse. 2010;64:449–459. doi: 10.1002/syn.20748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Tu Z, Jones LA, Vangveravong S, Wheeler KT, Mach RH. [3H]N-[4-(3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxyisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)butyl]-2-methoxy-5-methyl benzamide: a novel sigma-2 receptor probe. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;525:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi F, Grunder G, Biziere K, Stephane M, Dogan AS, Dannals RF, Ravert H, Suri A, Bramer S, Wong DF. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:248–259. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Weiss NT, Tarazi FI, Kula NS, Baldessarini RJ. Effects of alkylating agents on dopamine D3 receptors in rat brain: selective protection by dopamine. Brain Res. 1999;847:32–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]