Abstract

Anxiety, like other psychiatric disorders, is a complex neurobehavioral trait, making identification of causal genes difficult. In the present study, we examined anxiety-like behavior and fear conditioning in an F2 intercross of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. We identified numerous quantitative trait loci (QTL) influencing anxiety-like behavior in both open field and fear conditioning tests. Many of these QTL mapped back to the same chromosomal regions, regardless of behavior or test. For example, highly significant overlapping QTL on chromosome 1 were found in all fear conditioning measures as well as in center time measures in the open field. Other QTL exhibited strong temporal profiles over testing, highlighting dynamic relationship between genotype, test and changes in behavior. Next, we implemented a factor analysis design to account for the correlated nature of the behaviors measured. Open field and fear conditioning behaviors loaded onto four main factors representing both anxiety and fear behaviors. Using multiple QTL modeling we calculated the percent variance in anxiety and fear explained by multiple QTL using both additive and interactive terms. QTL modeling resulted in a broad description of the genetic architecture underlying anxiety and fear accounting for 14-37% of trait variance. Factor analysis and multiple QTL modeling revealed both unique and shared QTL for anxiety and fear; suggesting a partially overlapping genetic architecture for these two different models of anxiety.

Keywords: Anxiety, Fear, QTL, QTL Modeling, Open Field, Fear Conditioning, Mice

Introduction

Anxiety disorders affect 18% of people in the United States each year (Kessler et al 2005). These disorders are prevalent worldwide and debilitating to the people who suffer from them (Demyttenaere et al 2004). Anxiety disorders are variable in behavioral and psychological expression and therefore are likely to be affected by a diverse architecture of genetic factors. Some anxiety disorders are elicited by ambiguous stimuli whereas others are associated with distinct stimuli and thus more akin to an exaggerated fear response (i.e., General Anxiety Disorder vs. Phobia; Davis et al 2010). Both anxiety and fear are well defined psychological phenomena controlled by homologous brain regions in humans and experimental animal models (Davis, 1992; LeDoux 2000). Importantly, although both are modulated by amygdalar activity, anxiety and fear have independent neural pathways (see Davis et al 2010). Therefore it is likely that the genetic substrates of anxiety and fear will share some common and some unique genes. To date, few genes have been consistently identified by forward genetic studies that contribute to our understanding of the etiology of anxiety disorders in either human or animal studies (Yalcin et al 2004, Hovatta & Barlow 2008, Williams et al 2009).

Rodent models have been successfully used to measure anxiety and fear for decades. Classic paradigms such as the open field test (OF) and fear conditioning (FC) have been used to study innate anxiety and the development and maintenance of fear and anxiety through associative learning (Hall, 1934; Brown et al 1951). Common to most studies of anxiety and fear in rodents is the inter-correlated nature of the behaviors measured within tasks. For example, one frequent result from OF studies is a robust negative correlation between activity level (i.e. distance traveled) and anxiety (i.e., reduced center time). Using Principle Components Analysis, Milner and Crabbe (2008) showed that activity and anxiety were significantly negatively correlated in OF, light-dark and elevated plus-maze tests, but that activity and anxiety were not dissociable as independent factors. In another example, we selectively bred mice for high or low levels of contextual fear, which resulted in elevated anxiety and decreased activity across multiple paradigms (i.e. OF, elevated plus maze, etc; Ponder et al 2007). Our findings and those of others suggest that anxiety and activity are related traits and tests of anxiety (OF) and learned fear (FC) share a common genetic architecture (Milner & Crabbe 2008; López-Aumatell et al 2009 ).

In the present study, we looked at open field activity following saline injection and freezing behavior in a standard fear conditioning paradigm in an F2 cross of C57BL/6J (B6) and DBA/2J (D2) mice. Most of the behaviors measured were significantly correlated and we were able to identify many significant QTL. In order to reduce the number of independent tests and to explore the correlation structure in greater depth, we performed a factor analysis on all behavioral data with significant QTL. Anxiety and fear behaviors loaded onto four main factors which could be categorized based on loading strength, contextual fear, altered context/open field, cue based fear and cued-fear training. We also used a multiple QTL modeling approach on summary behavioral data to identify QTL of small effect obscured in our QTL analysis, as well as any potential interactions between QTL. Using both factor analysis and QTL modeling we were able to identify unique as well as QTL common for both anxiety and fear.

Materials and Methods

Animals and housing

Subjects were 612 F2 mice (305 male, 307 female) derived from an F1 cross between C57BL/6J (B6) female and DBA/2J (D2) male mice. Colony rooms were maintained on a 12:12h light-dark cycle with lights on at 0630h. Mice were housed in clear plastic cages with standard corn-cob bedding in same-sex groups of two to five mice with food and water available ad libitum. Testing was conducted during the light phase, between 0800 and 1700h, and mice acclimated to the testing room for a minimum of 30 minutes prior to testing for all tests. Mice were approximately 2 to 3 months of age (75.6 ± 0.3 days old, range: 62-90 days) on the first day of testing and all mice went through the identical testing sequence. First, open field (OF) behavior was measured as part of a locomotor testing paradigm. One week after locomotor testing mice began fear conditioning (FC). All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the University of Chicago’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Behavioral Testing

Open Field (OF)

The first day of locomotor testing provided OF behavior. The procedures for locomotor testing have previously been described in detail (Bryant et al 2009; Palmer et al 2005). Briefly, after acclimation mice were removed from the home cage and placed into individual holding cages with clean bedding for 5 min. After 5 min mice were weighed, injected i.p. with physiological saline (0.01mL/g body weight) and immediately placed in the center of the open field (AccuScan Instruments, Columbus, OH). Each open field chamber consisted of a clear acrylic arena (40 × 40 × 30 cm) placed inside a frame containing evenly spaced photocells and receptors. Each activity chamber was contained within a sound attenuating environmental chamber (AccuScan Instruments) with overhead lighting providing illumination (~80lux) and a fan in the rear wall that provided ventilation and masking of background noise. The mouse’s behavior was then measured by infrared beam break and converted into distance travelled (Versamax, AccuScan Instruments). Mice were allowed to explore the open field arena for 30 min, the first 10 min of which was used for OF behavior. Behaviors measured were distance traveled (cm) in the periphery (width: 10cm) and center (20 × 20cm) of the arena as well as time spent in the center (%) of the arena. After 30min mice were placed back in their home cage and the open field was cleaned with 10% isopropanol between tests. At the end of testing mice were returned to the vivarium.

Fear conditioning (FC)

FC procedures are identical to those described previously in Ponder et al (2007). Mice were tested in standard FC chambers (29 × 19 × 25cm with a stainless steel floor grid). A light on the top of the chamber provided dim illumination (~3 lux) and a fan provided a low level of masking background noise. Each chamber was housed within a sound attenuating chamber (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Chambers were cleaned with 10% isopropanol between animals. Behavior was recorded with digital video, acquired to computer and analyzed with FreezeFrame (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL). Freezing behavior was exported in 30-s blocks and also averaged into summary measures.

FC was conducted ten days after OF, and took place over 3 days. Each day, after acclimation, mice were placed individually into holding cages with clean bedding and transferred to the FC chambers for a 5 min trial. On day 1 baseline freezing was measured beginning 30-s after mice were placed into the test chambers and ending 150-s later (30s-180s; pre-training freezing). Mice were then exposed twice to the conditioned stimulus (CS), a 30-s tone (85 dB, 3 kHz) that co-terminated with the unconditioned stimulus (US), a 2-s, 0.5 mA foot shock delivered through the stainless steel floor grid. After each CS-US pairing there was a 30 s inter-trial interval (ITI) and freezing to tone on day 1 was measured by averaging the percent time spent freezing to each CS presentation (%freezing tone day 1). On day 2, the testing environment was identical to day 1 but no stimuli were presented. Percent of time freezing in response to the test chamber (%freezing context) was measured during the same period of time as pre-training freezing. On day 3, testing was altered in several ways: a different experimenter tested mice wearing different gloves, holding cages had no bedding, the shock grid, chamber door and one wall were covered with white plastic, yellow film was placed over the top of the chamber, chambers and plastic surfaces were scented and cleaned with a 0.1% acetic acid solution, and the vent fan was partially obstructed to change the background noise. From 30 – 180s, the percent of time freezing to the altered context (%freezing to altered context) was measured and then the tone-CS was presented as on day 1 with no US presentation. Average freezing to tone was calculated for days 1 and 3 by taking the average percent time freezing of each tone presentation (%freezing tone day 3).

QTL mapping

DNA from the F2 generation was extracted and genotyped by KBiosciences (Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, UK) using KASPar, a fluorescence-based PCR assay. 164 evenly spaced, informative markers selected from Petkov et al (2004) were used.

Phenotypic and genotypic data were imported into R/qtl for QTL mapping (Broman et al 2003). The “scanone” command was used to identify QTL for OF and FC data using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. For each analysis, p <0.05 significance levels were estimated using 1,000 permutations and 95% Bayesian credible intervals (Mb; Build 37) expanded to the nearest marker were calculated when significant QTL were found. Sex and age were also examined as both additive and/or interactive covariates.

For single QTL scans, OF data consisted of data for the entire 10 min of testing for all analyses: distance traveled periphery (cm), distance traveled center (cm), center time (%). The 10 min duration of the OF paradigm was chosen as locomotor activity habituates in the open field during the first 5 min (See Wahlsten1; Mouse Phenome Database(MPD), JAX). For single QTL scans of freezing behavior in FC, data were exported in 30-s bins for the entire 5 min test period. This time bin duration corresponds to the duration of the tone-CS presentation since the CS presentations on days 1 and 3 are discrete and punctate cues that differ greatly in salience from general exposure to the conditioning chamber.

Factor Analysis

Behavioral data exhibiting significant QTL (LOD p < 0.05, 1000 permutations) in the single QTL analysis were used in the factor analysis (SPSS 17.0, Chicago, IL). Raw behavioral data were used in the factor analysis and were not normalized and average behavioral data were used to replace missing data points (< 1.5% of all data cells). A preliminary dimension reduction of the data resulted in 6 factors (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Using a cutoff for initial Eigenvalues (~ 1.5 or larger) the factor analysis was suppressed to four factors and rerun. Behaviors and behavior time points with factor loadings < |.1| were suppressed and Varimax rotation was used.

Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Modeling

For QTL modeling, the “scantwo” command was used to test QTL under both full and additive models. Next QTL and QTL interactions were assessed by building stepwise models (“stepwiseqtl” command) for multiple QTL which used forward selection and backward elimination to identify the best QTL model of each behavior.

Stepwise modeling was conducted on summary data across tasks: distance traveled OF periphery, distance traveled OF center, %center time, %freezing tone day 1, %freezing context, %freezing altered context and %freezing tone day 3 (as described in FC methods above). In order to include multiple QTL within each model it was necessary to apply a penalty term for the addition of each new QTL to the model as well as a penalty for any QTL interactions. Penalties used in this analysis were determined by Broman and Sen (2009) with a simulated mouse genome, genotyped with evenly spaced markers: Additive penalty – 3.52, Heavy Interaction Penalty – 4.28, Light Interaction Penalty – 2.69. Each penalty term was subtracted from the LOD score of the model during the selection process.

Statistical Analyses

Correlations between behavioral measures were calculated using standard regression analyses. Percent variance for summary data and factor analysis QTL was computed using the following equation:

where LOD equals the peak LOD score and n the number of subjects for which genotype and phenotype data were available. Percent variance and significance of stepwise models were obtained by using the “fitqtl” command (Broman & Sen 2009).

Results

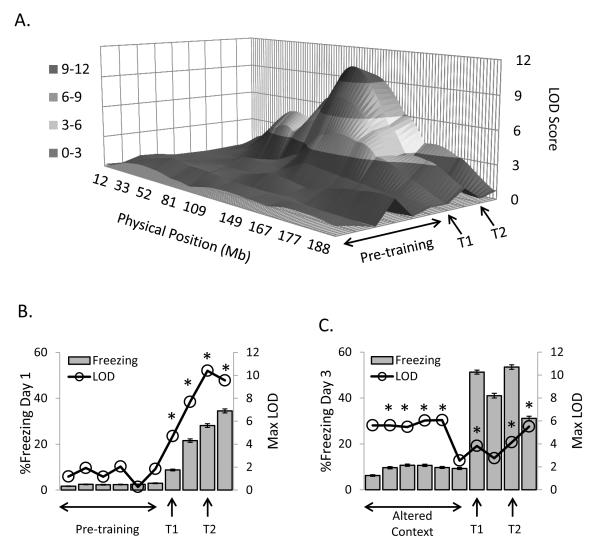

Single QTL mapping of multiple traits at several time points revealed numerous QTL at a genome-wide significance level of 0.05 (LOD threshold range 3.3-3.8). Specifically, over 20 QTL were identified on 12 chromosomes. Many of these QTL exhibited a temporal specificity. Figure 1A presents a 3-dimensional LOD score plot of a QTL on chromosome 1 for day 1 FC in 30-s time bins. This QTL is not significant until the first tone-CS presentation (LOD Peak: 4.7, genome-wide p<0.006). Figure 1B shows the relationship between %freezing and chromosome 1 LOD scores on day 1; illustrating the tight coupling between the change in freezing behavior and the emergence of the QTL. Figure 1C demonstrates the relationship between freezing behavior and LOD scores on day 3. Here the QTL on chromosome 1 is significant by the end of acclimation (LOD Peak: 5.5, p<0.0001) and stays elevated during the altered context exposure when %freezing is low. Peak LOD scores remain relatively stable even when %freezing increases dramatically with the presentation of the first CS. Therefore, utilizing the temporal profile of the behavior in the QTL analysis reveals important information about which aspects of the behavior influence this QTL.

Figure 1. 3-D LOD score plot for significant QTL on chromosome 1 exhibiting a temporal relationship with changes in freezing on Day 1.

A). 3-D representation of LOD scores for day 1 FC in 30-s time bins. The QTL is not significant until the first tone-CS presentation (T1). During each subsequent 30-s time bin (z-axis) the LOD score increases, peaking at the second CS presentation (T2). B). Relationship between %freezing (bars) and LOD scores (open symbols) on day 1 illustrates the relationship between changes in behavior and the emergence of the QTL. C). Relationship between %freezing (bars) and LOD scores (open symbols) on day 3. In contrast to day 1, the QTL precedes changes in behavior. The QTL is significant when freezing is low and does not increase during CS presentation when %freezing increases. *Significant LOD score, p < 0.05 (LOD score > 3.8).

Factor Analysis

Single QTL scans produced a multitude of significant QTL with varying temporal profiles (for examples see Fig S2-5). However, for the analysis of 33 behaviors a Bonferonni adjusted p-value for significance (p < 0.0015) would have resulted in far fewer significant QTL and thereby make it difficult to identify small-effect QTL. In order to better identify QTL unique to particular behavioral parameters, such as anxiety or fear, we used factor analysis to reduce the number of behaviors analyzed. All 33 behaviors with significant QTL identified in single QTL scans were used in the factor analysis. Based on initial Eigenvalues, dimension reduction was suppressed to four factors (see Methods). Loading weights for each of the factors are presented in Table 1. After rotation, each factor explained approximately 11% of the variance, in total explaining almost 44% of the total variance in behavior. Factors were ascribed the following descriptors based on loading strength: contextual fear (Factor 1), altered context/open field (Factor 2), cue based fear (Factor 3) and cued-fear training (Factor 4).

Table 1. Rotated Factor Matrix for behavioral data from the open field test and fear conditioning.

Bold font indicates factor where data load most heavily. Percent variance from the rotation sums of squared loadings and initial Eigenvalues are presented at the bottom of each factor

|

Factor

|

||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

| ||||

| Distance periphery | −.141 | −.288 | −.139 | |

| %Center time | −.214 | −.102 | −.132 | |

| Day 1: 90-120s | .222 | |||

| Day 1: Tone1 | .187 | .264 | .250 | .336 |

| Day 1: ITI | .281 | .408 | .611 | |

| Day 1: Tone2 | .221 | .474 | .549 | |

| Day 1:270-300s | .175 | .458 | .463 | |

| Day 2: Acclimation | .463 | .176 | .165 | .496 |

| Day 2: 30-60s | .488 | .168 | .152 | .555 |

| Day 2: 60-90s | .517 | .206 | .134 | .503 |

| Day 2: 90-120s | .589 | .180 | .189 | .458 |

| Day 2: 120-150s | .553 | .180 | .169 | .366 |

| Day 2: 150-180s | .567 | .193 | .158 | .331 |

| Day 2:Tone1 Time | .526 | .225 | .120 | .234 |

| Day 2: ITI Time | .530 | .188 | .134 | |

| Day 2:Tone 2 Time | .572 | .211 | .137 | |

| Day 2: 270-300s | .474 | .242 | .165 | |

| Day 3: Acclimation | .184 | .540 | .144 | .317 |

| Day 3: 30-60s | .207 | .565 | .287 | |

| Day 3: 60-90s | .288 | .597 | .113 | .268 |

| Day 3: 90-120s | .193 | .650 | .104 | .121 |

| Day 3: 120-150s | .192 | .590 | .105 | |

| Day 3: 150-180s | .200 | .575 | .155 | |

| Day 3: Tone1 | .157 | .640 | ||

| Day 3: ITI | .245 | .222 | .705 | .130 |

| Day 3:Tone2 | .215 | .755 | ||

| Day 3: 270-300s | .276 | .361 | .589 | .113 |

|

| ||||

| %Variance = 44.189% |

12.423 | 11.186 | 10.485 | 10.094 |

|

| ||||

| Initial Eigenvalue | 8.98 | 1.92 | 1.64 | 1.46 |

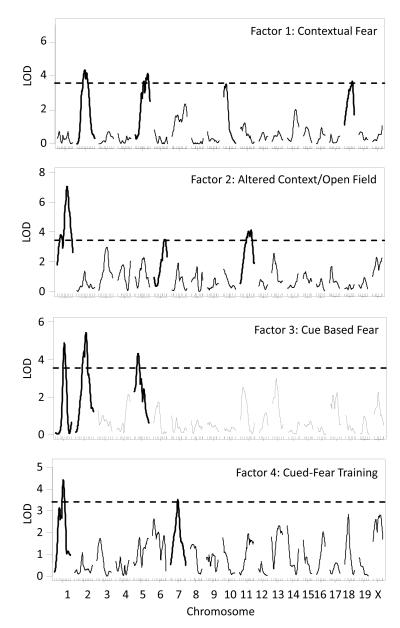

Figure 2 presents single QTL analyses of each of the four factors. LOD peak and QTL interval values are presented in Table 2. Each factor had multiple significant QTL and while some QTL overlapped, some factors had unique, non-overlapping QTL. For contextual fear (Factor 1), a novel QTL on chromosome 18 (95% Bayesian credible interval (CI): 46.0-76.3Mb) was identified that was not identified in the original QTL scans of raw data (Fig S2). Altered context/open field (Factor 2), was the only factor with a significant QTL on chromosome 6 (CI: 118.4-144.0Mb). Overlapping QTL on chromosomes 1 and 2 were found for two or more factors. A significant QTL on chromosome 1 was found for altered context/open field, cue based fear (Factor 3) and cued-fear training (Factor 4). Similarly, overlapping QTL on chromosome 2 were found for contextual and cue based fear. Contextual and cue based fear both had significant QTL on chromosome 5 but CI, when expanded to the nearest marker, did not overlap suggesting two distinct QTL on this chromosome (CI: 86.9-148.5Mb and 25.2-86.9Mb, respectively).

Figure 2. Genome-wide LOD scores for factors derived from the factor analysis of open field and fear conditioning data.

Dashed line represents the genome-wide significance threshold (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Summary of significant QTL from Factor Analysis and Summary Behavioral Data.

Significant QTL from genome-wide scans (rQTL; p<0.05).s QTL significant if sex was included as an interactive covariate. –F or –M indicate the sex with more anxiety-like behavior for a given allele. Behavior – see Methods for description; Chr – Chromosome; LOD Peak – Peak LOD score of QTL; 95% CI – 95% Bayesian Credible Interval (Mb; Build 37) expanded to the nearest SNP marker. %Variance - % of variance explained in behavior explained by QTL. Anxiety/Fear Allele – Allele associated with higher anxiety or elevated fear

| Behavior | Chr | LOD Peak | 95% CI (Mb) | %Variance | Anxiety/Fear Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 2 | 4.3 | 58.7 (57-116) | 3.2 | B6 |

| Contextual Fear | 5 | 4.1 | 61.5 (87-149) | 3.0 | B6 |

| 18 | 3.7 | 30.2 (46-76) | 2.7 | D2 | |

|

| |||||

| Factor 2 | 1 | 7.0 | 57.8 (109-167) | 5.1 | D2 |

| Altered Context/ | 6 | 3.5 | 25.6 (118-144) | 2.5 | D2 |

| Open Field | 11 | 5.9 | 32.2 (73-105) | 4.3 | B6 |

|

| |||||

| Factor 3 | 1 | 4.9 | 68 (81-149) | 5.1 | D2 |

| Cued-Fear Learning | 2 | 5.4 | 65.7 (74-140) | 2.5 | B6 |

| 5 | 4.3 | 61.8 (25-87) | 4.3 | D2 | |

|

| |||||

| Factor 4 | 1 | 4.4 | 96.7(52-149) | 3.2 | D2 |

| Cued-Fear Training | 7 | 3.5 | 34.2 (68-102) | 2.6 | D2 |

|

| |||||

| Distance Traveled – | 1 | 9.2 | 9.9 (167-177) | 5.6 | D2 |

| Periphery | 4 | 4.3 | 23.4 (125-148) | 3.1 | B6 |

| 11 | 7.6 | 33.6 (63-96) | 5.6 | B6 | |

| X | 5.3 | 76.6 (50-127) | 3.7 | B6 | |

|

| |||||

| Distance Traveled – | 1 | 8.0 | 39.4 (109-149) | 5.8 | D2 |

| Center | 5s | 5.0 | 42.3 (64-107) | 3.6 | D2-F |

| 6 | 7.7 | 55.4 (88-144) | 5.7 | D2 | |

| 13 | 3.5 | 71.8 (40-111) | 2.6 | D2 | |

| 17s | 5.0 | 49.9 (14-64) | 3.7 | B6-M | |

| X | 4.2 | 80.3 (10-90) | 3.1 | B6 | |

|

| |||||

| Center Time | 1 | 4.6 | 39.4 (81-149) | 3.4 | D2 |

| (%) | 5 | 5.5 | 42.3 (64-107) | 4.0 | D2 |

| 6 | 5.1 | 99.4 (32-132) | 3.7 | D2 | |

|

| |||||

| %Freezing | 1 | 11.2 | 68 (81-149) | 8.0 | D2 |

| Tone Day 1 | 2 | 5.1 | 82.4 (58-140) | 3.7 | B6 |

| X | 4.7 | 117.3 (96-127) | 3.4 | B6 | |

|

| |||||

| %Freezing | 1 | 4.4 | 68 (81-149) | 3.2 | D2 |

| Context | 2 | 5.6 | 58.7 (58-117) | 4.1 | B6 |

| 5 | 5.3 | 19.4 (121-140) | 3.9 | D2 | |

| 10 | 4.6 | 30.8 (16-47) | 3.4 | B6 | |

|

| |||||

| %Freezing | 1 | 7.6 | 68 (81-149) | 5.5 | D2 |

| Altered | 2 | 4.3 | 58.7 (58-117) | 3.1 | B6 |

| Context | 5 | 3.9 | 68.5 (64-133) | 2.8 | D2 |

| 10 | 3.8 | 30.8 (16-47) | 2.8 | B6 | |

| 11s | 4.8 | 43 (63-106) | 3.6 | B6-F | |

| %Freezing | 1 | 5.2 | 68 (81-149) | 3.8 | D2 |

| Tone Day 3 | 2 | 6.1 | 58.7 (81-149) | 4.4 | B6 |

| 5 | 5.0 | 95.3 (25-121) | 3.7 | D2 | |

| 13 | 3.8 | 45 (40-85) | 2.8 | D2 | |

Factor analysis revealed a QTL on chromosome 1 common to both anxiety and fear whereas the QTL on chromosome 6 was specific to anxiety and the QTL on chromosome 2 specific to fear. In general, factor analysis resulted in a reduced number of QTL due in part to reduced LOD scores resulting from the universal loading of this correlated behavioral dataset onto multiple factors (Table 1). Factor analysis may have highlighted the QTL accounting for the highest %variance for behavioral data comprising each factor but CI were still large (range: 25.6-96.7MB) and the %variance of the anxiety-like behaviors explained by any given QTL was still small (range: 2.5-5.1%; Table 2).

Summary Measures

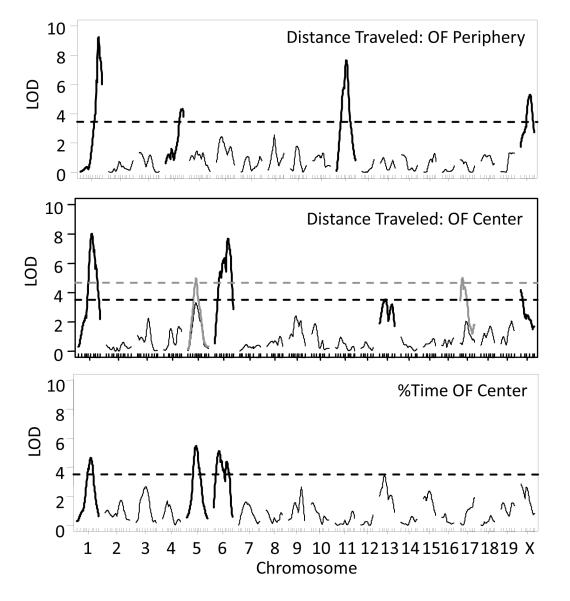

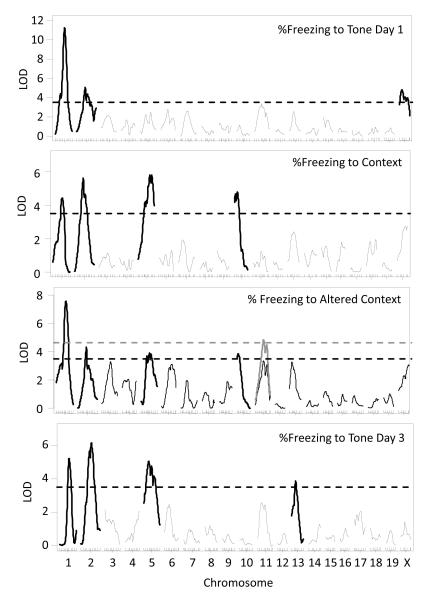

Factor analysis results ultimately identified summary measures we have typically analyzed (i.e. %freezing to context; see Ponder et al 2007). In fact, correlations between behaviors were always strongest within tasks and days and between adjacent time points (Table S1). For FC, correlations were highest within a day of testing but correlated most strongly within to the context and tone periods. Therefore, we returned to summary measures of both OF and FC for multiple QTL modeling. Figure 3 presents LOD scores from QTL scans of OF behaviors and Figure 4 presents LOD scores from QTL analyses for FC (for direct comparison of summary measures to factor analysis results see Fig S6). Similar to results from the factor analysis, QTL scans of summary measures resulted in the identification of numerous QTL, many which overlapped and some of which were unique to a particular measure. On average, however, using summary measures resulted in higher peak LOD scores, 5.5 vs. 4.6 (see Table 2). Significant QTL on chromosome 1 were again identified in both anxiety and fear paradigms as well as a QTL on chromosome 5 (Table 2). As in the factor analysis the QTL on chromosome 6 only mapped to anxiety behaviors and the chromosome 2 QTL was specific to fear.

Figure 3. Genome-wide LOD scores for open field behavior (OF).

Single QTL analysis results for OF measures: distance traveled in the periphery (cm/10min; top chart), distance traveled in the center (cm/10min; middle chart) and % time in the center of the arena (bottom chart). Grey QTL traces indicate LOD scores when sex is included as and interactive covariate. Black (no covariate) and grey (sex as interactive covariate) LOD thresholds represent significance at p < 0.05.

Figure 4. Genome-wide LOD scores for fear conditioning (FC) freezing behavior.

Single QTL analysis results for FC measures: %freezing to tone day 1, %freezing to context, %freezing to altered context and %freezing to tone day 3. Grey QTL traces indicate LOD scores when sex is included as and interactive covariate. Black (no covariate) and grey (sex as interactive covariate) LOD thresholds represent significance at p < 0.05.

Multiple QTL Modeling

In an attempt to identify epistatic interactions between QTL we used the “scantwo” command to test for epistatic interactions genome-wide (Table S2). “scantwo” analyses did not identify any significant epistatic interactions from pairwise QTL tests although a number of suggestive interactions for FC measures, %freezing altered context and %freezing to tone day 3 were found (Full vs. Additive LOD >3.8). Phenotypes and genotypes were subsequently analyzed using the “stepwiseqtl” QTL model search algorithm.

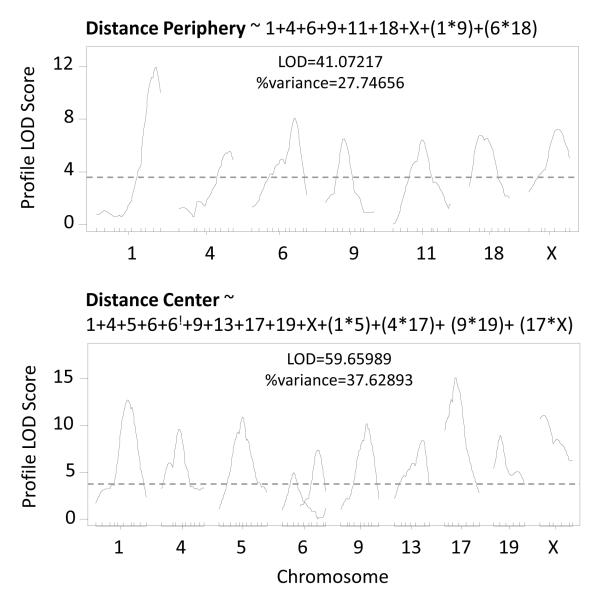

Using forward selection and backward elimination, stepwise modeling indicated QTL interactions and QTL for most summary measures. Figure 5 presents multiple QTL models of distance traveled in the periphery and center of the OF. The equation above each figure represents the model with the best penalized LOD score following forward selection and backward elimination. Three new QTL were identified for distance traveled in the periphery on chromosomes 6, 9 and 18. The model search algorithm also identified two QTL interactions, one between chromosomes 1 and 9 and the other between chromosomes 6 and 18. Similarly, for distance traveled in the center of OF, new QTL were identified on chromosomes 4, 9 and 19. For distance traveled in the center four interactions were identified.

Figure 5. Stepwise QTL models of OF behavior with QTL interactions.

Models selection results for distance traveled in the periphery and center and corresponding profile LOD score plots. Interactions are represented as QTL products (i.e. (1*2)). ! indicates a second QTL position on a previously identified chromosome.

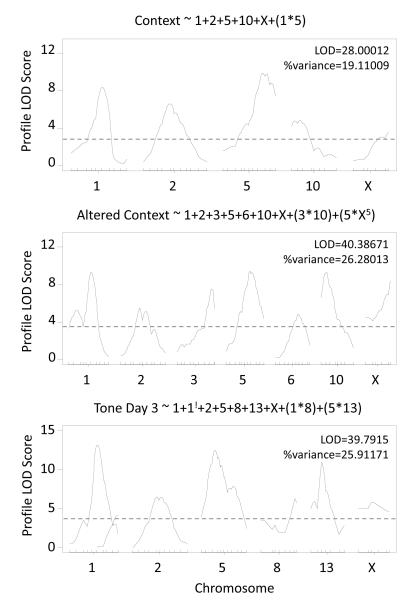

Figure 6 presents multiple QTL models of %freezing to context, %freezing to altered context and %freezing to tone day 3 from FC. For %freezing to context, like distance traveled in the center of the OF, an interaction between chromosomes 1 and 5 was identified. Three new QTL were found for %freezing to altered context on chromosomes 3, 6, and X as well as two interactions; both interactions were identified in the “scantwo” analysis but LOD scores were only suggestive (LODi ~ 4.0). One new QTL on chromosome 8 was selected for the model of %freezing to tone day 3 as well as a second locus on chromosome 1 (Figure 6) and interactions were selected between QTL on chromosome 1 and 8 and chromosomes 5 and 13. This interaction between QTL on chromosome 5 and 13 was also identified in the “scantwo” analysis but again the LOD score was only suggestive (LODi = 3.88).

Figure 6.

Stepwise QTL models of FC behavior with QTL interactions. Models selection results for %freezing to context, %freezing to altered context and %freezing to tone day 3. Interactions are represented as QTL products (i.e. (1 Ö 5)). ! Second QTL position on a previously identiï¬ ed chromosome.

Table 3 presents the QTL results of the model search algorithm. Both additive models and models with interacting QTL were highly significant and explained 14-37% of the phenotypic variance in OF and FC measures. Overall, stepwise modeling of QTL resulted in the identification of novel QTL, replication of previously identified QTL and a substantial increase in the %variance of each summary measure explained by QTL. QTL modeling, like factor analysis and single QTL scans of summary measures, identified QTL on chromosome 1 and 5 for both anxiety and fear measures but also suggested an interaction between these two loci. A more proximal QTL on chromosome 6 still mapped exclusively to anxiety measures from the center of the OF and QTL on chromosome 2 only mapped to FC measures.

Table 3. Stepwise QTL Models of OF and FC behaviors.

Significant additive and interactive models (all p < 6.6−16) created using a Stepwise modeling approach

| Behavior | Model - chromosome pos (cM) |

Model

LOD |

%Variance

Model |

| Distance – Periphery |

179 + 467 + 657 + 924 + 1138.6 + 1814 + X39 + (179*924) + (657*1814) | 41.07 | 27.75 |

| Distance – Center |

154 + 430 + 539.2 + 619.5 + 660 + 943 + 1348 + 1718 + 1910 + X6 + (154*539.2) + (430*1718) + (943*1910) + (1718*X6) |

59.66 | 37.63 |

| Center Time (%) |

153 + 537 + 622 + 950 | 19.62 | 14.38 |

| Tone Day 1 | 146.6 + 241.8 + X31 | 21.46 | 15 |

| Context | 148 + 240 + 561 + 1013 + X54.3 + (148*561) | 28 | 19.11 |

| Altered Context |

148 + 241.8 + 374 + 551 + 648 + 1011 + X54.3 + (374*1011) + (551*X54.3) | 40.39 | 26.28 |

| Tone Day 3 | 149 + 184 + 244 + 524 + 861 + 1319.1 + X23 + (148*861) + (524*1319.1) | 39.79 | 25.91 |

Discussion

In the present study we used factor analysis and QTL modeling in an attempt to delineate the genetic architecture underlying anxiety and fear in an F2 cross of B6 and D2 mice. In preliminary single QTL scans the temporal nature of QTL, especially for fear measures, was revealed (see Fig 1). Both factor analysis and QTL modeling provided additional information about the relationship between anxiety and fear but had opposite effects on QTL discovery. Anxiety and fear behavioral measures were significantly correlated to each other and the loading of an activity measure (distance traveled) and an anxiety measure (center time) onto a single factor supports previous findings that the two measures are not independent in most tests of anxiety (Brigman et al 2009; Henderson et al 2004; Milner & Crabbe, 2008). Furthermore, overlapping QTL for anxiety and fear from factor analyses supports our previous finding that selection based on %freezing to context results in selection for anxiety measures as well (Ponder et al 2007).

Factor analysis identified QTL not originally seen in the single QTL scans but ultimately identified “test session factors” (Henderson et al 2004) and did not result in more resolved QTL identification (i.e., small effect QTL or narrow intervals). Henderson et al (2004) used factor analysis in a QTL study of anxiety (but not fear) using multiple behavioral tasks. Similar to the present study the authors concluded that the use of summary measures corresponding to test or test session was more appropriate for identifying genetic loci, especially those loci accounting for a small amount of the trait variance (Henderson et al 2004). In the present study, QTL analysis of summary measures (Figures 3 and 4) did result in higher LOD peak scores and comparable Bayesian credible intervals (CI) with a marginal improvement in the percent variance of the phenotype that was captured by each QTL (Table 2).

Using summary data from OF and FC measures we performed a QTL model search algorithm to identify additive or interactive QTL models accounting for a greater percentage of trait variance in this F2 population. Stepwise modeling resulted in an improvement the amount of variance in behavior explained by each model, accounting for 14-37% of trait variance depending on the measure (Table 3). In general, OF activity measures had more significant QTL and stronger models (27-37% of variance) than center time (14%) a result consistent with previous studies in which activity measures produce much stronger LOD scores than time measures in anxiety tests (Henderson et al 2004). QTL modeling did identify QTL of small effect not found in single QTL scans or QTL analysis of factors, for example a QTL on chromosome 9 for OF (Figure 5). Similarly, a QTL was identified on chromosome 17 for distance traveled in the center of the OF but only if sex was included as an interactive covariate (i.e., B6 males low activity in OF center). This QTL was also identified with QTL modeling and overlaps with a QTL previously identified in an F2 cross of LG/J and SM/J mice for startle response where males had a greater startle response than females (Samocha et al 2010). The overlap of these two QTL in different strains of mice for different measures of anxiety-like behavior provides strong evidence for a sex-specific effect of this contributing locus on chromosome 17. Finally, the CI for the QTL on chromosome 17 includes Glo1, a gene we and other investigators have found to be involved in differences in anxiety-like behavior (Hovatta et al 2005; Williams et al 2009).

Many of the QTL identified replicate QTL identified in previous studies using B6 and D2 mice. Significant QTL on chromosomes 1, 2 and 10 were previously identified for contextual fear, freezing in the altered context and cue based fear in a B6XD2 F2 intercross (Wehner et al 1997). These 3 chromosomal regions were further validated in a line of B6XD2 mice selected for contextual fear (Radcliffe et al 2000) with similar allele effects to those found in the present study (Table 2). Specifically, on chromosome 1 the D2 allele is the high anxiety/fear allele whereas the B6 allele is the high anxiety/fear allele for chromosomes 2 and 10 (Radcliffe et al 2000). Furthermore, consistent with our previous analysis of a selected line of B6XD2 mice selected for freezing to context, QTL identified in the current study spanned intervals including significantly associated SNPs and differential gene expression in hippocampal tissue on chromosomes 1, 4, 5 and 13 (Ponder et al 2007).

In almost every QTL analysis conducted in the present study, a significant QTL was identified on chromosome 1. All chromosome 1 QTL had overlapping CI (80.6-148.8 Mb) with the exception of a non-overlapping QTL for distance traveled in the periphery of the OF (167.1-177.1 Mb; Fig S5). Significant QTL on chromosome 1 have been identified in numerous studies of anxiety-like behavior in multiple crosses of mouse strains as well as heterogeneous stock (HS) mice (Caldarone et al 1997; Henderson et al 2004; Talbot et al 2003; Valdar et al 2006; Wehner et al 1997). The overlapping CI of the QTL on chromosome 1 for anxiety and fear measures includes the gene Rgs2 which has been shown to affect anxiety-like behavior in tests of unlearned fear (OF; Yalcin et al 2004). This region also includes Mcm6, a gene we found to be differentially expressed in the hippocampus of mice selected for elevated freezing to context (Ponder et al 2007). The more distal QTL on chromosome 1 found for distance traveled in the periphery was recently identified in for a OF distance traveled in an F2 cross of B6 and C58/J mice (Eisener-Dorman et al 2010). This distal QTL has a CI overlapping with Qrr1 (172.5-177.5 Mb), a region with a high proportion of trans-eQTL in neural tissue associated with numerous physiological and behavioral traits (Mozhui et al 2008).

Another QTL that has previously been reported for anxiety and fear-related traits (Ponder et al 2007, Valdar et al 2006) was also identified on chromosome 5 for both OF and FC measures. The model search algorithm identified an interaction between chromosome 5 and chromosome 1 for both distance traveled in the center of the OF as well as freezing to context in FC. Using the overlapping CI for the QTL on chromosome 1 for both behaviors (CI: 109.3-148.7 Mb; Table 2) we ran a search on WebQTL, an extensive database of QTL, mRNA expression and trait data for B6 and D2 mice (www.genenetwork.org; Chesler et al 2004). We identified 133 differentially expressed genes (LOD ≥ 3.26, Supplemental Table 4) in whole brain tissue of B6XD2 F2 mice and 137 differentially expressed genes in hippocampal tissue of B6XD2 recombinant inbred lines (RIL) within our CI interval on chromosome 1. With QTL modeling results indicating an interaction between QTL on chromosomes 1 and 5, we took those differentially expressed genes on chromosome 1 and looked for significant trans eQTL on chromosome 5. Of those differentially expressed genes, only 11 had significant trans eQTL within the CI on chromosome 5, for freezing to context (CI: 120.5-140Mb), Trip12, Farp2, Phlpp, Lpgat1, Ccnt2, Ubxd2,Pfkfb2, Mdm4, Rnpep, Camsap1l1,Kif14. If the interaction between QTL on chromosomes 1 and 5 is validated, QTL modeling in combination with bioinformatic tools may allow for the identification of candidate genes, even in low resolution QTL analyses like the F2 intercross.

Though many of the QTL presented here replicate results of previous studies some novel QTL were also discovered. In contrast to well documented QTL, like the QTL on chromosome 1, these results must be interpreted with caution. Specifically, because multiple QTL analyses were performed on multiple behaviors some or all of these novel QTL may in fact be false discoveries. For example, QTL on chromosomes 7, 8, 9, 17, 18 and 19 were identified only in the factor analysis and QTL modeling steps. Using the GeneNetwork database, we conducted a search of phenotypes for B6XD2 RIL related to those measured in the present study and specifically looked for suggestive or significant LOD scores (≥ 2.5) for QTL on these chromosomes (Table 4). For all 6 chromosomes we found evidence to support the QTL findings of the current study. We are currently using a B6 × D2 advanced intercross line to replicate and fine-map these QTLs.

Table 4. QTL in B6×D2 RIL lines for phenotypes related to OF and FC.

Suggestive and significant QTL (LOD ≥ 2.5) for traits in the GeneNetwork database related to anxiety and fear. Keyword search: Fear, Anxiety, Open Field and Fear Conditioning. For novel QTL found in the present study this table presents corresponding QTL found in other studies utilizing both similar and different experimental assays. Chr – Chromosome; QTL Peak – Mb position of peak LOD score; Trait IDs – GeneNetwork trait ID number

| Chr | QTL peak (Mb) |

Trait IDs | Experimental Assay | LOD | Publication |

|

| |||||

| 7 | 64 35 |

11390 10898 |

Light Dark Plus Maze |

2.80 2.76 |

Philip et al 2009 Yang et al 2008 |

|

| |||||

| 8 | 72 | 10675 | Amygdalar Volume | 3.59 | Yang et al 2008 |

|

| |||||

| 9 | 52 35 57 57 73 |

12362 11917 10075 10505 11868 |

Zero Maze Fear Conditioning Open Field Open Field Open Field |

3.30 2.96 3.02 4.59 3.80 |

Cook et al 2009 Philip et al 2009 Crabbe et al 1983 Plomin et al 1991 Philip et al 2009 |

|

| |||||

| 17 | 65 57 |

11724 10446 |

Open Field Fear Conditioning |

3.04 3.61 |

Philip et al 2009 Owen et al 1997 |

|

| |||||

| 18 | 84 | 11620 | Open Field | 3.63 | Philip et al 2009 |

|

| |||||

| 19 | 15 17 |

12341 11659 |

Zero Maze Fear Conditioning |

4.09 2.56 |

Cook et al 2009 Philip et al 2009 |

As in most F2 studies, the primary limitation in the present experiment is QTL mapping resolution. The majority of QTL identified had 95% CI greater than 40 Mb and even the smallest interval of 10 Mb on chromosome 1 for distance traveled in the periphery contains hundreds of genes. In an attempt to overcome mapping resolution issues we used factor analysis to reduce the number of behaviors measured and in parallel QTL modeling to identify small effect QTL but each approach has limitations with respect to interpretation of the results. QTL analysis of behavioral factors was greatly affected by the universal loading of most behavioral data onto each of the four factors (Table 1). In fact, if a more stringent Eigenvalue cutoff had been employed (i.e., Eigenvalues > 2; Henderson et al 2004; Milner & Crabbe 2008) only one factor would have been obtained. Results from QTL modeling must also be interpreted with care and considered exploratory in nature as p-values for each QTL do not account for other QTL included in the model (Broman & Sen 2009). Current methods of QTL mapping in heterogeneous stocks (HS), outbred populations and advanced intercross lines have the potential to provide single-gene resolution (Cheng et al 2010, Flint et al 2005, Flint 2010, Valdar et al 2006, Yalcin et al 2010) and subsequently these populations should be more robust for identifying precise epistatic interactions between significant loci when multiple QTL modeling is employed

In summary, we identified, and in some cases replicated, multiple QTL for OF and FC with multiple analysis approaches. Anxiety and fear had both overlapping and non-overlapping QTL suggesting some portion of shared genetic architecture which is consistent with anatomical (e.g. Davis 1992; Davis et al 2010; LeDoux 2000) and genetic data (e.g. Ponder et al 2007; López-Aumatell et al 2009). The relationship between anxiety and fear was further supported by our factor analysis results showing that all behavioral measures from OF and FC are significantly correlated. QTL modeling results improved the amount of phenotypic variance explained by QTL with the identification of small effect QTL as well as QTL interactions. QTL modeling, especially in high resolution mapping populations like advanced intercross lines and outbred populations, may prove to be useful for identifying the dynamic gene interactions and large gene networks that underlie complex and variable traits like anxiety and fear and ultimately replicate and refine the results presented here. Further delineation of both the shared and non-overlapping genetic architecture of anxiety and fear will provide a clearer understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying both traits and hopefully lead to the identification of potential therapeutic targets ideally suited for specific anxiety disorders in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant 5R01MH079103 awarded to AAP. The authors would like to acknowledge GeneNetwork (http://www.genenetwork.org) for providing bionformatic tools and public data that have contributed to this manuscript (funded by: The UT Center for Integrative and Translational Genomics; NIAAA (U01AA13499, U24AA13513, U01AA014425); NIDA, NIMH, and NIAAA (P20-DA 21131); NCI MMHCC (U01CA105417); NCRR BIRN, (U24 RR021760). The authors would also like to acknowledge Ryan Walters for assistance with husbandry and behavioral testing.

References

- Brigman JL, Mathur P, Lu L, Williams RW, Holmes A. Genetic relationship between anxiety-related and fear-related behavior in BXD recombinant inbred mice. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2009;20:204–209. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c368c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Wu H, Sen Ś , Churchill GA. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:889–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Sen S. A Guide to QTL Mapping with R/qtl. Springer; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Kalish HI, Farber IE. Conditioned fear as revealed by magnitude of startle response to an auditory stimulus. Exp Psychol. 1951;41:317–328. doi: 10.1037/h0060166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CD, Chang HP, Zhang J, Wiltshire T, Tarantino LM, Palmer AA. A major QTL on chromosome 11 influences psychostimulant and opioid sensitivity in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:795–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarone B, Saavedra C, Tartaglia K, Wehner JM, Dudek BC, Flaherty L. Quantitative trait loci analysis affecting contextual conditioning in mice. Nat Genetics. 1997;17:335–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler EJ, Lu L, Wang J, Williams RW, Manly KF. WebQTL: rapid exploratory analysis of gene expression and genetic networks for brain and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:485–486. doi: 10.1038/nn0504-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M, Lu L, Williams RW. BXD Published Phenotypes. GeneNetwork. 2009 http://www.genenetwork.org. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Kosobud A, Young ER, Janowsky JS. Polygenic and single-gene determination of responses to ethanol in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mouse strains. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1983;5:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear-potentiated startle: implications for animal models of anxiety. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90014-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Miles L, Grillon C. Phasic vs sustained fear in rats and humans: role of the extended amygdala in fear vs anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:105–35. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisener-Dorman AF, Grabowski-Boase L, Steffy BM, Wiltshire T, Tarantino LM. Quantitative trait locus and haplotype mapping in closely related inbred strains identifies a locus for open field behavior. Mammalian Genome. 2010;21:231–246. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9260-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J. Mapping quantitative traits and strategies to find quantitative trait genes. Methods. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.07.007. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, Valdar W, Shifman S, Mott R. Strategies for mapping and cloning quantitative trait genes in rodents. Nat Rev: Genetics. 2005;6:271–286. doi: 10.1038/nrg1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. Emotional behavior in the rat. I. Defecation and urination as measures of individual differences in emotionality. J Comp Psychol. 1934;18:385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ND, Turri M, DeFries JC, Flint J. QTL Analysis of Multiple Behavioral Measures of Anxiety in Mice. Behavior Genetics. 2004;34:267–293. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000017872.25069.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Barlow C. Molecular genetics of anxiety in mice and men. Annals of Medicine. 2008;40:92–109. doi: 10.1080/07853890701747096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Tennant RS, Helton R, Marr RA, Singer O, et al. Glyoxalase 1 and glutathione reductase 1 regulate anxiety in mice. Nature. 2005;438:662–666. doi: 10.1038/nature04250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Aumatell R, Vicens-Costa E, Guitart-Masipa M, Martínez-Membrives E, Valdar W, et al. Unlearned anxiety predicts learned fear: A comparison among heterogeneous rats and the Roman rat strains. Behav Brain Res. 2009;202:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner LC, Crabbe JC. Three murine anxiety models: results from multiple inbred strain comparisons. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozhui K, Ciobanu DC, Schikorski T, Wang X, Lu L, Williams RW. Dissection of a QTL hotspot on mouse distal chromosome 1 that modulates neurobehavioral phenotypes and gene expression. PLos Genet. 2008;4:e1000260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000260. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen EH, Christensen SC, Paylor R, Wehner JM. Identification of quantitative trait loci involved in contextual and auditory-cued fear conditioning in BXD recombinant inbred strains. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:292–300. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AA, Verbitsky M, Suresh R, Kamens HM, Reed CL, et al. Gene expression differences in mice divergently selected for methamphetamine sensitivity. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:291–305. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov PM, Ding Y, Cassell MA, Zhang W, Wagner G, et al. An efficient SNP system for mouse genome scanning and elucidating strain relationships. Genome Res. 2004;9:1806–1811. doi: 10.1101/gr.2825804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip VM, Duvvuru S, Gomero B, Ansah TA, Blaha CD, et al. High-throughput behavioral phenotyping in the expanded panel of BXD recombinant inbred strains. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:129–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, McClearn GE, Gora-Maslak G, Neiderhiser JM. Use of recombinant inbred strains to detect quantitative trait loci associated with behavior. Behav Genet. 1991;21:99–116. doi: 10.1007/BF01066330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder CA, Kliethermes CL, Drew MR, Muller J, Das K, Risbrough VB, Crabbe JC, Gilliam TC, Palmer AA. Selection for contextual fear conditioning affects anxiety-like behaviors and gene expression. Genes Brain and Behav. 2007;6:736–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe RA, Lowe MV, Wehner JM. Confirmation of contextual fear conditioning QTLs by short-term selection. Behav Genet. 2000;30:183–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1001910107167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot CJ, Radcliffe RA, Fullerton J, Hitzemann R, Wehner JM, Flint J. Finescale mapping of a genetic locus for conditioned fear. Mamm Genome. 2003;14:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-3059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdar W, Solberg LC, Gaugier D, Burnett S, Klenerman P, Cookson WO, Taylor M, Rawlins JNP, Mott R, Flint J. Genome-wide genetic association of complex traits in outbred mice. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(8):879–87. doi: 10.1038/ng1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner JM, Radcliffe RA, Rosmann ST, Christensen SC, Rasmussen DL, Fulker DW, Wiles M. Quantitative trait locus analysis of contextual fear conditioning in mice. Nat Genetics. 1997;17:331–334. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R, IV, Lim JE, Harr B, Wing C, Walters R, et al. A common and unstable copy number variant is associated with differences in Glo1 expression and anxiety-like behavior. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004649. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang RJ, Mozhui K, Karlsson RM, Cameron HA, Williams RW, Holmes A. Variation in mouse basolateral amygdala volume is associated with differences in stress reactivity and fear learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2595–2604. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin B, Willis-Owen SA, Fullerton J, Meesaq A, Deacon RM, Rawlins JN, Copley RR, Morris AP, Flint J, Mott R. Genetic dissection of a behavioral quantitative trait locus shows that Rgs2 modulates anxiety in mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1197–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin B, Nicod J, Bhomra A, Davidson S, Cleak J, et al. Commercially Available Outbred Mice for Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9):e1001085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001085. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.