Abstract

CK2 is a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase involved in biological processes such as embryonic development, circadian rhythms, inflammation and cancer. Biochemical experiments have implicated CK2 in the control of several cellular processes and in the regulation of signal transduction pathways. Our laboratory is interested in characterizing the cellular, signaling and molecular mechanisms regulated by CK2 during early embryonic development. For this purpose, animal models, including mice deficient in CK2 genes, are indispensable tools. Using CK2α gene deficient mice, we have recently shown that CK2α is a critical regulator of mid-gestational morphogenetic processes, as CK2α deficiency results in defects in heart, brain, pharyngeal arch, tail bud, limb bud and somite formation. Morphogenetic processes depend upon the precise coordination of essential cellular processes in which CK2 has been implicated, such as proliferation and survival. Here we summarize the overall phenotype found in CK2α−/− mice and describe our initial analysis aimed to identify the cellular processes affected in CK2α mutants.

Keywords: CK2, morphogenesis, embryo development, proliferation, apoptosis

Introduction

CK2 is a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase with orthologs in all eukaryotes from plants to yeast to mammals. CK2 is involved in important biological processes such as embryonic development [1–4], circadian rhythms [5], inflammation [6] and cancer [7, 8]. CK2 regulates essential cellular processes such as viability [9], cell proliferation and growth [10], cell survival [11], cell fate specification [12–14], differentiation [15, 16], metabolism [17], cell cytoarchitecture [18] and migration [19].

In mammals, two different genes encode for CK2 kinases, CK2α and CK2α ’. CK2α and CK2α ' can be found as monomeric kinases and as a tetrameric holoenzyme composed of two catalytic subunits, CK2α and/or CK2α ', and two regulatory subunits, CK2β [20–22]. CK2β changes CK2α/α' substrate specificity and confers CK2 holoenzyme membrane binding ability [23, 24]. CK2β also has CK2α/α'-independent roles [25, 26]. The importance of CK2 in morphogenetic processes during mammalian embryonic development is reflected in the phenotypes obtained upon genetic depletion of the CK2 genes in mice [1–3, 27]. CK2α’ gene deficiency results in viable offspring, but leads to male sterility with oligospermia and sperm displaying defective head morphogenesis [1]. CK2β gene deficiency leads to early post-implantation lethality at embryonic day (E) 6.5 with embryos showing no preamniotic canal and an inner cell mass with a small, probably blastocoelic, cavity [2]. Conditional deletion of CK2β in embryonic neural stem cells leads to telencephalic defects including absence of oligodendroglial cells at the corpus callosum level and of the emerging hippocampal dentate gyrus [27]. CK2α gene deficient mice die by embryonic day (E)11 and display abnormal heart tube, hypoplastic limb buds and pharyngeal aches, open neural tube and tailbud defects [3, 7]. In this report we revise the phenotypic features found in CK2α−/− mice and describe initial analysis identifying cellular processes affected in CK2α mutant embryos.

Materials and methods

Freshly dissected embryos were collected at embryonic day E9.5 and E10.5, photographed in an Olympus SZX16 stereomicroscope, washed in PBS and fixed overnight at 4°C with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. The following day, embryos were dehydrated and stored at 4°C, or embedded and sectioned [12]. To examine differences in somite size, photographs from four somite-matched pairs of CK2α+/+ and CK2α−/− embryos were used to measure the area and perimeter of selected somites using CANVAS software. Measured area and perimeter of somites 5 and 16 was analyzed with a t-test (Excel).

For whole-mount TUNEL/ anti-phospho-histone H3/Ser10 (anti-phH3) staining, three pairs of somite-paired CK2α−/− and CK2α+/+ embryos were hydrated, treated with 10 µg/ml of proteinase K/ 10mM Tris HCl pH 7.5 for 10–15 min at room temperature (RT) and stopped in 2 mg/ml glycine in 1× PBS/0.1% Tween (PBSt) for 10 min at RT. Embryos were then washed 3× in PBSt and stained for TUNEL with an in situ cell death detection kit, fluorescein (ROCHE) following manufacturer’s instructions. After TUNEL staining, embryos were washed in PBSt and blocked in 10% goat serum/PBSt for 1 h at RT. Embryos were then washed, incubated with anti-phH3 (Upstate) at 1:500 in PBSt for 1.5 h at RT, washed and incubated with anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 (Invitrogen) at 1:1000 in the same buffer for 1 hour at RT. Then, embryos were washed, counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen) at 1:10.000 for 5 min at RT, washed and stored in PBSt at 4°C. Embryos were rocking in all the steps except for the TUNEL incubation. In each experiment, as a positive control for TUNEL, an additional embryo was treated with RQ1-DNase (Promega), and, as a negative control, another embryo was treated with a solution without TUNEL enzyme and incubated without primary antibody. Stained embryos were photographed in an Olympus SZX16 stereomicroscope. Pictures were pseudocolored using ImageJ (NIH).

For TUNEL/ phH3 staining in sections, slides with comparable sections of two pairs of somite-paired CK2α−/− and CK2α+/+ embryos were warmed, deparaffinized and hydrated. Sections were circled with a Pap Pen (Ted Pella, Inc.) and slides were treated with 10 µg/ml of proteinase K/ 10mM Tris HCl pH 7.5 for 15 min at RT. Slides were rinsed twice in 1× PBS and stained for TUNEL as described above. After TUNEL staining, slides were washed in 1× PBSt and blocked in 10% goat serum/PBSt for 1 h at RT. Slides were then washed, incubated with antiphH3 at 1:200 in 1% goat serum/PBSt for 1 h at RT, washed and incubated with anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 at 1:400 in the same buffer for 1 h at RT. One section of each slide was treated with RQ1-DNase as a positive control for TUNEL, and another section, incubated with a solution without TUNEL enzyme and no phH3 antibody, served as a negative control. Slides were counterstained with DAPI as described above, mounted with ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes, Inc.) and photographed in a Nikon Eclipse TE-2000E/Photometrics CoolSnap HQ2 camera with NIS-elements software. Pictures were pseudocolored and overlayed using ImageJ. Total nuclei and antibody-stained nuclei were counted, percentage of positive cells/total number of cells calculated (mitotic and apoptotic indexes), and significance analyzed with a Wilcoxon rank sum test (R software). p values <0.05 were considered significant. Represented mitotic index values are mean ± standard deviation.

RT-qPCR analysis was performed as described in [28] and radioactive RT-PCR as described in [12] in two pairs of somite-paired CK2α−/− and CK2α+/+ embryos. The number of amplification cycles was optimized to ensure that the PCR reaction was within its linear range. Primers: 5’- TCTTCAAAGACCCAGGGATG-3’ and 5’-GGACTGAAAGCCAGACGAAG-3’ for delta-like 1 (Dll1); 5’-TGAGGGAGAGCGCAGGCTCAAG-3’ and 5’TGCTGTCCACGATG GACGTAAGG-3’ for myogenin; 5’-GCCCCTCAACTGTCTCTCTG-3’ and 5’-GGGAGCT GTTTTCTCGACTG-3’ for Sal-like 4 (Sall4).

Results and discussion

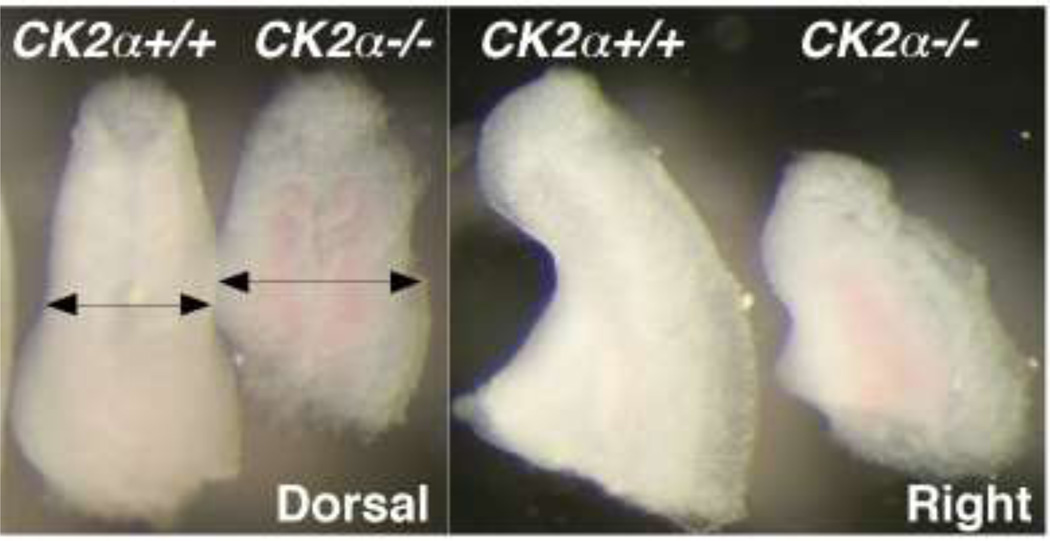

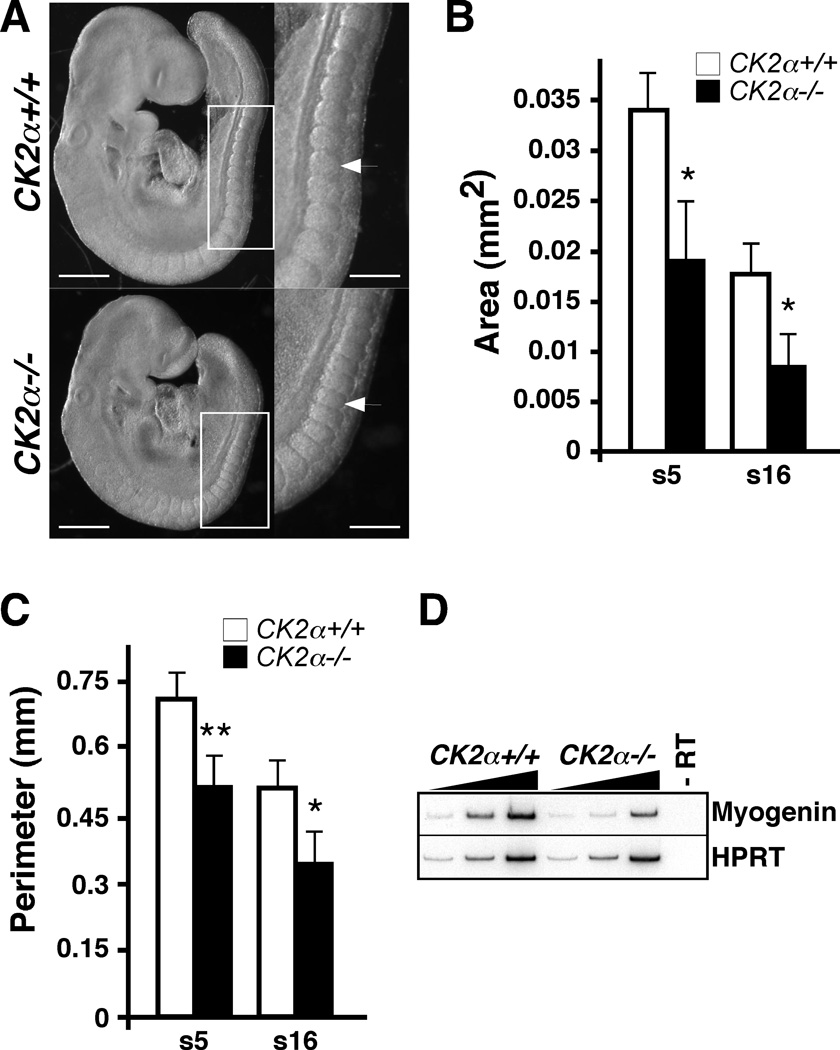

Heterozygous CK2α mutant mice have a normal life span and, so far, seem phenotypically normal. In contrast, CK2α−/− embryos die in utero around E11. Embryonic defects in CK2α−/− embryos were apparent at E9.5. At E9.5, 95% of CK2α−/− embryos displayed open neural tubes at the midbrain level (Table 1) in contrast to 18% of wild-type (WT) embryos. Defects in the pharyngeal arches (precursors of cranial nerves, skeletal and muscle elements in the face and pharynx) are also observed at E9.5. Thus, 84% of WT embryos had developed first and second pharyngeal arches while 85% of CK2α−/− embryos had only a hypoplastic first pharyngeal arch and 10% of embryos had no pharyngeal arches (Table 1). Defects in pharyngeal arch formation persist as embryos age, and at E10.5 the total number of pharyngeal arches is diminished in CK2α−/− embryos compared to WT embryos [3]. E9.5 CK2α−/− mutants also show hypoplastic fore and hindlimb buds compared to WT embryos (Table 1) and defective tail bud shape (Table 1, Fig. 1). In addition to these defects, we also observed hypoplastic somites (masses of mesoderm on the sides of the neural tube that will form vertebrae, muscle, and dermis) (Fig. 2A). In order to quantify the effect of CK2α depletion on somite size, we measured the area and perimeter of somites number 5 and 16 in four E9.5 somite-matched embryo pairs. There was a statistically significant decrease in the somite area of both somites (approximately 50%, p=0.006) and a significant decrease in somite perimeter of both somites (approximately 30%, p<0.02)(Fig 2B). In addition, CK2α−/− embryos display cardiac malformations described and analyzed elsewhere (Degano et al., submitted). CK2α−/− embryos probably die of cardiac malfunction, as none of the other defects would be embryonic lethal at this stage of development, although this needs to be confirmed in conditionally deleted CK2α mice.

Table 1.

Phenotype of CK2α−/− embryos at E9.5

| Tissue | Percent embryos |

CK2α+/+ | CK2α+/− | CK2α−/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharyngeal arches | Two | 84 | 88 | 15 |

| One | 16 | 12 | 85 | |

| None | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| # embryos | 19 | 34 | 20 | |

| Neural tube | Closed | 82 | 88 | 5 |

| Open | 18 | 12 | 95 | |

| # embryos | 22 | 34 | 21 | |

| Tailbud | Normal | 62 | 63 | 5 |

| Broad | 38 | 37 | 95 | |

| # embryos | 21 | 30 | 20 | |

| Forelimb | Present | 75 | 88 | 43 |

| Not present | 25 | 12 | 57 | |

| # embryos | 20 | 33 | 21 | |

Fig. 1. Photographs of tail buds of E9.5 WT and CK2α−/− embryos.

Dorsal and right views of CK2α+/+ and CK2α−/− embryos at somite pairs (22–23). Arrows show the in increased tail bud width in CK2α−/− embryos. Representative photographs of over 70 embryo litters.

Fig. 2. Phenotype of E9.5 CK2α−/− embryos.

(A) Right: right view of 22 somite pair CK2α+/+ and CK2α−/− embryos (Scale bar: 0.5 mm); left: magnified images of the squares on the right (Scale bar: 0.25 mm). Arrow indicates somite number 16. Somites 5 (s5) and 16 (s16) were analyzed for area and perimeter. Histogram showing average somite area (B) and perimeter (C) +/− standard deviation. (*) denotes p<0.05; (**) denotes p<0.005. (D) Decrease in Myogenin transcript expression in CK2α mutant compared to WT embryos by radioactive RT-PCR. Increasing PCR cycles for both CK2α−/− and CK2α+/+ are shown. (-RT) Control minus reverse transcriptase.

Previously, we found that engrailed-1, a neural marker gene, and T/brachyury, a notochord and primitive streak marker gene, were expressed at similar levels in CK2α−/− embryos compared to WT embryos [3, 7]. In contrast, myogenin, a transcription factor involved in skeletal muscle development, was downregulated in CK2α−/− embryos compared to CK2α+/+ (Fig. 2C) by radioactive RT-PCR. In addition, preliminary RT-qPCR analysis showed that, compared to CK2α+/+, CK2α−/− embryos had a decrease of 15 % on Delta-like 1 (Dll1), a Notch ligand involved in somite development, and of 28 % on Sal-like 4 (Sall4), a transcription factor involved in pattern formation and cell specification important for heart, limb and brain development [29]. These data are in accordance with the defects in somites, limbs and heart observed in CK2α−/− embryos.

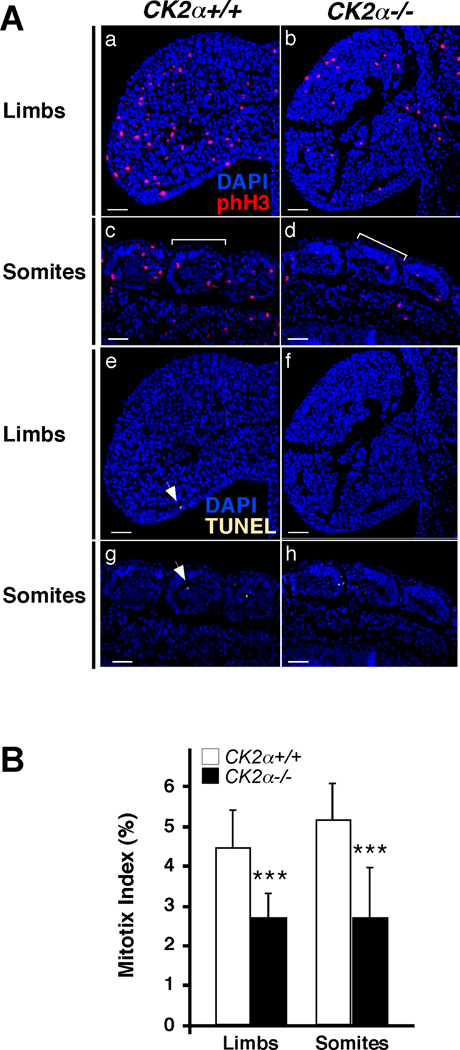

Since several embryonic regions were hypoplastic in CK2α−/− embryos, we tested whether proliferation or apoptosis were affected in CK2α−/− embryos. To test this, we used embryos at E9.5 and E10.5 (before CK2α−/− embryonic death) to analyze proliferation by phospho-histone H3/Ser10 (phH3) staining and apoptosis by TUNEL staining by whole-mount immunohistochemistry (WIHC). In WT embryos, phH3+ cells were readily detected while TUNEL+ cells were rarely detected (Fig. 3). In CK2α−/− embryos there was a decrease in phH3+ cells particularly noticeable in pharyngeal arches, limb buds, somites, tailbud and the heart (Fig. 3, 4). However, we did not observe an effect on TUNEL staining in tissues affected in CK2α−/− embryos including limb buds, somites, heart and pharyngeal arches (Fig. 3). Negative controls showed no staining and positive control for TUNEL showed staining in all nuclei (not shown). To quantify the effects on proliferation and apoptosis, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) in sections of forelimb buds and somites, from two pairs of E10.5 WT and CK2α mutants (32–35 somites)(Fig. 5A). Similar to the WIHC staining, a number of phH3+ cells were detected by IHC in forelimb buds and somites while little TUNEL staining was observed. The mitotic index (number of phH3+ cells/ number of DAPI+ cells) in CK2α mutants was decreased by 40% in limb buds (p<0.0001) and by 50% in somites (p<0.0001) compared to WT embryos (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the apoptotic index (number of TUNEL+ cells/ number of DAPI+ cells) did not change in the forelimb buds (apoptotic index=0.12, p=0.6) and somites (apoptotic index=0.75, p=0.28) among genotypes. Negative controls showed no staining and positive controls for TUNEL showed staining in all nuclei (not shown). These results show that CK2α is required for proliferation during early embryogenesis. These data suggest that diminished proliferation, but not increased apoptosis, may explain the defects observed in CK2α−/− embryos. We are currently determining the mechanism(s) underlying the proliferation defects in CK2α−/− mice.

Fig. 3. Proliferation and apoptosis in E9.5 and E10.5 CK2α−/− embryos.

(A, B) E9.5 embryos (22–24 somite pairs) were stained by WIHC for phH3 (red, A) and TUNEL (green, B). (C) E10.5 embryos (32–34 somite pairs) were stained by WIHC for phH3 (red) and TUNEL (green). Photographs show bright field (BF), and phH3 and TUNEL staining. Fluorescent images were pseudo-colored. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. Arrowheads point to different embryonic tissues. Abbreviations: fl: forelimb bud; h: heart; hl; hindlimb bud; p1: first pharyngeal arch; s: somite.

Fig. 4. Head, limb buds and tailbud of E10.5 CK2α−/− embryos.

Magnified images of E10.5 embryos (32–34 somite pairs) stained with phH3. Abbreviations: AER: apical ectodermal ridge; di: diencephalon; fl: forelimb bud; hl; hindlimb bud; mes: mesencehalon; met: metencephalon; mye: myelencephalon; p1: first pharyngeal arch; p2: second pharyngeal arch; s: somite; tb: tail bud; tel: telencephalon.

Fig. 5. Proliferation in E10.5 forelimb buds and somites.

(A) Composite phH3 (red)/ DAPI (blue) photographs (a to d) and TUNEL (yellow)/ DAPI (blue) photographs (e to h) of limbs and somites. Bracket indicates one somite. Arrows point to TUNEL+ cells. Fluorescent images were pseudo-colored. Scale bar: 50 µm (B) Histogram represents the average mitotic index (total number of phH3+ cells/ number of DAPI+ cells) +/− standard deviation. A total of 15 sections per tissue were counted from two pairs of CK2α+/+ and CK2α−/− embryos. (***) denotes p<0.0005.

This predominant role for CK2α in proliferation during early mouse development was somehow surprising, as in vitro experiments showed a role for CK2 in both cell proliferation and survival. For example, depletion of CK2 activity with antisense oligonucleotides (AS ODN) and siRNA technology in cells in culture leads typically to a 40–50% decrease in CK2 activity correlating with 50% decreased cell viability and/or 50–100% decrease in proliferation [30–34]. In contrast, genetic CK2α depletion leads to an 80% decrease in CK2 activity [7] with no apparent effects in apoptosis (Fig. 3). Similar to CK2α mutants, CK2β gene deficiency leads to lethality at E6.5 probably due to defects in proliferation and not apoptosis [2]. The mechanism underlying the decreased proliferation is not yet known; analysis of CK2β+/− embryonic stem (ES) cells showed no effects on growth rate and G1- and G2-checkpoints [35]. Similarly, conditional deletion of CK2β in embryonic neural stem cells leads to telencephalic defects caused by decreased proliferation and defective oligodendrogenesis but not to defects in apoptosis [27]. These data suggest that, during embryonic development, CK2α and CK2β are mainly controlling cell proliferation. CK2α mutants display reduced levels of CK2β at E10.5, therefore, part or all the effects of CK2α depletion on proliferation could be due to the downregulation of CK2β. Rescue experiments with stabilized forms of CK2β should address the role that CK2β plays in the CK2α−/− proliferative defects.

In contrast to CK2α and CK2β mutants, CK2α’ gene deficiency results in viable offspring but leads to male sterility [1]. Sperm display defective head morphogenesis and spermatids had increased apoptosis, however, the underlying cause for the morphogenetic and apoptotic defects are not known [36]. These data suggest that CK2α' may be involved in cell survival during embryonic development. CK2α−/− embryos seem to have normal levels of CK2α' by immunoblot and that may explain the lack of effect in apoptosis in this mutant mice. One question that arises is whether the combined depletion of CK2α/CK2α' or CK2α/CK2α' will result in defects in both proliferation and apoptosis.

Determining the cellular processes controlled by the different CK2 subunits during embryonic development requires a detailed analysis of their endogenous expression pattern. CK2 is expressed in all tissues by northern and immunoblot analysis [1, 37, 38], however, detailed analysis of CK2α and CK2β transcripts and proteins in sections in late-gestation mouse embryos revealed that, even though CK2α and CK2β are expressed in all mouse embryo tissues, there is a spatial and temporal regulation in their expression [39]. Determining the effect that deficiency on one of the three genes has on the levels and expression pattern of the others will help us to address the potential compensation between subunits. For example, could the restriction of the CK2α' phenotype to the testis due to lineage restricted expression pattern and/or it could be due to compensation by CK2α?; and are the levels of CK2α' elevated in specific tissues in CK2α mutant mice? This could be inferred from data showing that in lung cell lines, CK2α’ protein levels can rise after CK2α depletion by siRNA [40], however, this is not true for other cell lines [41]. Subsequent studies of the mechanism of CK2 differential expression in embryos may help understand how CK2 expression is upregulated in cancers.

In summary, CK2 loss of function and gain of function experiments in animal models show the key role that the different CK2 subunits have during animal embryonic development, in particular in morphogenesis. These animal models are also helping decipher which of the cellular functions assigned to CK2 are affected at different times of development and also in adulthood (see articles by David Seldin and Heike Rebholz in this issue); and they allow us to test and confirm predictions derived from biochemical experiments, such as the dependence of CK2β levels on the presence of CK2α [41, 30, 40, 7]. Molecular studies in these animal models will help address the biological role of CK2 in signaling pathways, such as Wnt, EGF, TGFβ, FGF, Activin, Notch and adiponectin [42–44, 8, 45–52, 13]; and future proteomic analysis in these animal models will be helpful to determine which of the in vitro identified substrates [53] plays a role in controlling the development or function of particular tissues during embryogenesis and in adulthood.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mirka Hlavacova, Patrick Hogan and Taimur Khan for technical assistance and mouse colony management. We will like to thank Mike Kirber, the director of the BUSM Imaging core facilities for his help. This work was supported with funding from the American Heart Association (SDG 0735521T), the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA71796), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P01 ES11624), a Pilot grant from the Department of Medicine of Boston University School of Medicine (to I.D.) and a Beatriu de Pinos postdoctoral fellowship from the Catalonian Government (to I.R.D.).

References

- 1.Xu X, Toselli PA, Russell LD, Seldin DC. Globozoospermia in mice lacking the casein kinase II alpha' catalytic subunit. Nat Genet. 1999;23(1):118–121. doi: 10.1038/12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchou T, Vernet M, Blond O, Jensen HH, Pointu H, Olsen BB, Cochet C, Issinger OG, Boldyreff B. Disruption of the regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 in mice leads to a cell-autonomous defect and early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(3):908–915. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.908-915.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lou DY, Dominguez I, Toselli P, Landesman-Bollag E, O'Brien C, Seldin DC. The alpha catalytic subunit of protein kinase CK2 is required for mouse embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(1):131–139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno-Romero J, Espunya MC, Platara M, Arino J, Martinez MC. A role for protein kinase CK2 in plant development: evidence obtained using a dominant-negative mutant. Plant J. 2008;55(1):118–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allada R, Meissner RA. Casein kinase 2, circadian clocks, and the flight from mutagenic light. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274(1–2):141–149. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-2943-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh NN, Ramji DP. Protein kinase CK2, an important regulator of the inflammatory response? J Mol Med. 2008;86(8):887–897. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seldin DC, Lou DY, Toselli P, Landesman-Bollag E, Dominguez I. Gene targeting of CK2 catalytic subunits. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;316(1–2):141–147. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez I, Sonenshein GE, Seldin DC. Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: CK2 and its role in Wnt and NF-kappaB signaling: linking development and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(11–12):1850–1857. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-9153-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padmanabha R, Chen-Wu JL, Hanna DE, Glover CV. Isolation, sequencing, and disruption of the yeast CKA2 gene: casein kinase II is essential for viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(8):4089–4099. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J. 2003;369(Pt 1):1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad KA, Wang G, Unger G, Slaton J, Ahmed K. Protein kinase CK2--a key suppressor of apoptosis. Advances in enzyme regulation. 2008;48:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dominguez I, Mizuno J, Wu H, Song DH, Symes K, Seldin DC. Protein kinase CK2 is required for dorsal axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2004;274(1):110–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bose A, Kahali B, Zhang S, Lin JM, Allada R, Karandikar U, Bidwai AP. Drosophila CK2 regulates lateral-inhibition during eye and bristle development. Mech Dev. 2006;123(9):649–664. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dominguez I, Mizuno J, Wu H, Imbrie GA, Symes K, Seldin DC. A role for CK2alpha/beta in Xenopus early embryonic development. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274(1–2):125–131. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietz KN, Miller PJ, Hollenbach AD. Phosphorylation of serine 205 by the protein kinase CK2 persists on Pax3-FOXO1, but not Pax3, throughout early myogenic differentiation. Biochemistry. 2009;48(49):11786–11795. doi: 10.1021/bi9012947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerra B, Issinger OG. Protein kinase CK2 and its role in cellular proliferation, development and pathology. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(2):391–408. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990201)20:2<391::AID-ELPS391>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riera M, Peracchia G, Pages M. Distinctive features of plant protein kinase CK2. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;227(1–2):119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canton DA, Litchfield DW. The shape of things to come: an emerging role for protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of cell morphology and the cytoskeleton. Cell Signal. 2006;18(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramerov AA, Saghizadeh M, Caballero S, Shaw LC, Li Calzi S, Bretner M, Montenarh M, Pinna LA, Grant MB, Ljubimov AV. Inhibition of protein kinase CK2 suppresses angiogenesis and hematopoietic stem cell recruitment to retinal neovascularization sites. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;316(1–2):177–186. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9831-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filhol O, Martiel JL, Cochet C. Protein kinase CK2: a new view of an old molecular complex. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(4):351–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornburg W, Lindell TJ. Purification of rat liver nuclear protein kinase NII. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(19):6660–6665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsten ME, Litchfield DW. Order or chaos? An evaluation of the regulation of protein kinase CK2. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82(6):681–693. doi: 10.1139/o04-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinna LA. The raison d'etre of constitutively active protein kinases: the lesson of CK2. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36(6):378–384. doi: 10.1021/ar020164f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarrouilhe D, Filhol O, Leroy D, Bonello G, Baudry M, Chambaz EM, Cochet C. The tight association of protein kinase CK2 with plasma membranes is mediated by a specific domain of its regulatory beta-subunit. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1403(2):199–210. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bibby AC, Litchfield DW. The Multiple Personalities of the Regulatory Subunit of Protein Kinase CK2: CK2 Dependent and CK2 Independent Roles Reveal a Secret Identity for CK2beta. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1(2):67–79. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolanos-Garcia VM, Fernandez-Recio J, Allende JE, Blundell TL. Identifying interaction motifs in CK2beta - a ubiquitous kinase regulatory subunit. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31(12):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huillard E, Ziercher L, Blond O, Wong M, Deloulme JC, Souchelnytskyi S, Baudier J, Cochet C, Buchou T. Disruption of CK2beta in embryonic neural stem cells compromises proliferation and oligodendrogenesis in the mouse telencephalon. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(11):2737–2749. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01566-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currier N, Solomon SE, Demicco EG, Chang DL, Farago M, Ying H, Dominguez I, Sonenshein GE, Cardiff RD, Xiao ZX, Sherr DH, Seldin DC. Oncogenic signaling pathways activated in DMBA-induced mouse mammary tumors. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33(6):726–737. doi: 10.1080/01926230500352226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren M, Wang W, Spiden S, Chen-Murchie D, Tannahill D, Steel KP, Bradley A. A Sall4 mutant mouse model useful for studying the role of Sall4 in early embryonic development and organogenesis. Genesis. 2007;45(1):51–58. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seeber S, Issinger OG, Holm T, Kristensen LP, Guerra B. Validation of protein kinase CK2 as oncological target. Apoptosis. 2005;10(4):875–885. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-0380-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu D, Hensel J, Hilgraf R, Abbasian M, Pornillos O, Deyanat-Yazdi G, Hua XH, Cox S. Inhibition of protein kinase CK2 expression and activity blocks tumor cell growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;333(1–2):159–167. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Davis A, Yu S, Ahmed K. Response of cancer cells to molecular interruption of the CK2 signal. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;227(1–2):167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faust RA, Tawfic S, Davis AT, Bubash LA, Ahmed K. Antisense oligonucleotides against protein kinase CK2-alpha inhibit growth of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in vitro. Head Neck. 2000;22(4):341–346. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200007)22:4<341::aid-hed5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zien P, Duncan JS, Skierski J, Bretner M, Litchfield DW, Shugar D. Tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBBt) and tetrabromobenzimidazole (TBBz) as selective inhibitors of protein kinase CK2: evaluation of their effects on cells and different molecular forms of human CK2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754(1–2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blond O, Jensen HH, Buchou T, Cochet C, Issinger OG, Boldyreff B. Knocking out the regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 in mice: gene dosage effects in ES cells and embryos. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274(1–2):31–37. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escalier D, Silvius D, Xu X. Spermatogenesis of mice lacking CK2alpha': failure of germ cell survival and characteristic modifications of the spermatid nucleus. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;66(2):190–201. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerra B, Siemer S, Boldyreff B, Issinger OG. Protein kinase CK2: evidence for a protein kinase CK2beta subunit fraction, devoid of the catalytic CK2alpha subunit, in mouse brain and testicles. FEBS Lett. 1999;462(3):353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orlandini M, Semplici F, Ferruzzi R, Meggio F, Pinna LA, Oliviero S. Protein kinase CK2alpha' is induced by serum as a delayed early gene and cooperates with Ha-ras in fibroblast transformation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(33):21291–21297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mestres P, Boldyreff B, Ebensperger C, Hameister H, Issinger OG. Expression of casein kinase 2 during mouse embryogenesis. Acta Anat (Basel) 1994;149(1):13–20. doi: 10.1159/000147550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yde CW, Olsen BB, Meek D, Watanabe N, Guerra B. The regulatory beta-subunit of protein kinase CK2 regulates cell-cycle progression at the onset of mitosis. Oncogene. 2008;27(37):4986–4997. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seldin DC, Landesman-Bollag E, Farago M, Currier N, Lou D, Dominguez I. CK2 as a positive regulator of Wnt signalling and tumourigenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274(1–2):63–67. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu H, Symes K, Seldin DC, Dominguez I. Threonine 393 of beta-catenin regulates interaction with Axin. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108(1):52–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song DH, Dominguez I, Mizuno J, Kaut M, Mohr SC, Seldin DC. CK2 phosphorylation of the armadillo repeat region of beta-catenin potentiates Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(26):24018–24025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song DH, Sussman DJ, Seldin DC. Endogenous protein kinase CK2 participates in Wnt Signaling in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(31):23790–23797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909107199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao Y, Wang HY. Casein kinase 2 Is activated and essential for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(27):18394–18400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji H, Wang J, Nika H, Hawke D, Keezer S, Ge Q, Fang B, Fang X, Fang D, Litchfield DW, Aldape K, Lu Z. EGF-induced ERK activation promotes CK2-mediated disassociation of alpha-Catenin from beta-Catenin and transactivation of beta-Catenin. Mol Cell. 2009;36(4):547–559. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh NN, Ramji DP. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of the apolipoprotein E gene requires c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38 kinase, and casein kinase 2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(6):1323–1329. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000220383.19192.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cavin LG, Romieu-Mourez R, Panta GR, Sun J, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS, Sonenshein GE, Arsura M. Inhibition of CK2 activity by TGF-beta1 promotes IkappaB-alpha protein stabilization and apoptosis of immortalized hepatocytes. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 2003;38(6):1540–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailly K, Soulet F, Leroy D, Amalric F, Bouche G. Uncoupling of cell proliferation and differentiation activities of basic fibroblast growth factor. Faseb J. 2000;14(2):333–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filhol O, Nueda A, Martel V, Gerber-Scokaert D, Benitez MJ, Souchier C, Saoudi Y, Cochet C. Live-cell fluorescence imaging reveals the dynamics of protein kinase CK2 individual subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(3):975–987. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.975-987.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee NY, Haney JC, Sogani J, Blobe GC. Casein kinase 2beta as a novel enhancer of activin-like receptor-1 signaling. Faseb J. 2009;23(11):3712–3721. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heiker JT, Wottawah CM, Juhl C, Kosel D, Morl K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Protein kinase CK2 interacts with adiponectin receptor 1 and participates in adiponectin signaling. Cell Signal. 2009;21(6):936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meggio F, Pinna LA. One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? Faseb J. 2003;17(3):349–368. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0473rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]