Abstract

Methamphetamine (METH) induces stereotypy, which is characterized as inflexible, repetitive behavior. Enhanced activation of the patch compartment of the striatum has been correlated with stereotypy, suggesting that stereotypy may be related to preferential activation of this region. However, the specific contribution of the patch compartment to METH-induced stereotypy is not clear. In order to elucidate the involvement of the patch compartment to the development of METH-induced stereotypy, we determined if destruction of this sub-region altered METH-induced behaviors. Animals were bilaterally infused in the striatum with the neurotoxin dermorphin-saporin (DERM-SAP; 17 ng/μl) to specifically ablate the neurons of the patch compartment. Eight days later, animals were treated with METH (7.5 mg/kg), placed in activity chambers, observed for 2h and sacrificed. DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly reduced the number and total area of mu-labeled patches in the striatum. DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly reduced the intensity of METH-induced stereotypy and the spatial immobility typically observed with METH-induced stereotypy. In support of this observation, DERM-SAP pretreatment also significantly increased locomotor activity in METH-treated animals. In the striatum, DERM-SAP pretreatment attenuated METH-induced c-Fos expression in the patch compartment, while enhancing METH-induced c-Fos expression in the matrix compartment. DERM-SAP pretreatment followed by METH administration augmented c-Fos expression in the SNpc and reduced METH-induced c-Fos expression in the SNpr. In the medial prefrontal, but not sensorimotor cortex, c-Fos and zif/268 expression was increased following METH treatment in animals pre-treated with DERM-SAP. These data indicate that the patch compartment is necessary for the expression of repetitive behaviors and suggests that alterations in activity in the basal ganglia may contribute to this phenomenon.

Keywords: psychostimulant, immediate early gene, behavior, basal ganglia, cortex

1. Introduction

The striatum is a component of the basal ganglia that is critically important in the regulation of movement and alterations in the function of the striatum contribute to the development of movement disorders (Crittenden and Graybiel, 2011). The striatum can be divided into the patch (striosome) and matrix compartments that are delineated based on their differential expression of neuropeptides and receptors, as well as their connectivity (Crittenden and Graybiel, 2011, Gerfen et al., 1985, Gerfen and Wilson, 1996, Gerfen and Young, 1988, Graybiel, 1990). For example, the patch compartment receives input from limbic regions, such as the prelimbic cortex and amygdala, while the matrix compartment receives input from sensorimotor and associative forebrain regions (Bolam et al., 1988, Gerfen, 1984, McDonald, 1992, Ragsdale and Graybiel, 1988). The specific functions of these compartments are not completely understood, but several lines of data, including metabolic studies (Brown et al., 2002), intracranial self-stimulation studies (White and Hiroi, 1998), and enhanced immediate early gene activity (Canales and Graybiel, 2000, Graybiel et al., 1990, Horner and Keefe, 2006, Horner et al., 2010, Moratalla et al., 1992, Tan et al., 2000, Wang et al., 1995) and neuropeptide expression (Adams et al., 2003, Fagergren et al., 2003, Horner and Keefe, 2006, Horner et al., 2010, Wang et al., 1995) in the patch versus matrix compartments following psychostimulant treatment indicate that the patch and matrix compartments may sub-serve different aspects of motor activity and behavior.

Stereotypy is defined as the development of abnormally repetitive motor actions that coincides with an inability to initiate normal adaptive responses, and can occur as a result of treatment with high or repeated doses of psychostimulants, such as methamphetamine (METH) (Canales and Graybiel, 2000, Graybiel et al., 1990, Graybiel and Rausch, 2000, Horner et al., 2010). It has been suggested that psychostimulant-induced stereotypic behaviors may be related to enhanced activation of the patch compartment relative to the surrounding matrix compartment, as the relative degree of c-Fos expression in the patch compartment in rostral striatum correlates with the development of stereotypic behavior following psychostimulant treatment (Canales and Graybiel, 2000). Interestingly, this relationship was specific for the rostral aspects of striatum, as there was not a significant correlation between psychostimulant-induced patch-enhanced c-Fos expression and stereotypy in mid-level striatum (Canales and Graybiel, 2000). While recent data suggests that an imbalance in the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor circuits that transverse the striatum may also contribute to psychostimulant-induced stereotypy (Aliane et al., 2009), the precise role of patch-based circuits in the development of stereotypic behaviors in response to psychostimulant treatment is not clear.

In order to address the role of the neurochemically distinct patch compartment in the genesis of psychostimulant-induced stereotypy, we utilized the neurotoxin dermorphin-saporin (Lawhorn et al., 2009, Tokuno et al., 2002) to specifically ablate the neurons that comprise the patch compartment prior to METH treatment. The neurons of the patch compartment express a high density of mu opioid receptors, while the neurons of the matrix compartment contain relatively few mu opioid receptors (Herkenham and Pert, 1981, Pert et al., 1976, Tempel and Zukin, 1987). Dermorphin is a potent mu opioid receptor agonist that induces internalization of mu opioid receptors upon binding (Giagnoni et al., 1984), while saporin is a ribosome-inactivating cytotoxin (Wiley and Kline, 2000). Thus, internalization of the DERM-SAP complex will ultimately lead to the destruction of mu opioid receptor-containing neurons (such as those found in the patch compartment of striatum), while leaving non-mu opioid receptor expressing neurons (such as the majority of those found in the matrix) relatively intact.

The goal of this study was to determine whether preferential ablation of the patch compartment altered the development of stereotypic behavior following a high dose of methamphetamine. We then examined the impact of patch compartment lesions on METH-induced c-Fos expression in the patch and matrix compartments of rostral striatum, as well as in the nucleus accumbens. We also examined whether ablation of patch-based circuits would alter METH-induced c-Fos activity in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), which receives specific input from the patch compartment, and provides dopaminergic input to the striatum (Fujiyama et al., 2011, Gerfen et al., 1985, Jimenez-Castellanos and Graybiel, 1989, Tokuno et al., 2002). Finally, in order to determine if ablation of the patch compartment might have an impact on basal ganglia output, we examined METH-induced c-Fos activation in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr), the main output nucleus of the basal ganglia, as well as c-Fos activation and zif/268 mRNA expression in the frontal cortex, the ultimate target of basal ganglia-based circuits (Gerfen, 1984, Gerfen and Wilson, 1996).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA), weighing 250–350g were used in all experiments. Rats were housed in groups of four in plastic cages in a temperature-controlled room. Rats were on a 14:10 h light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All animal care and experimental manipulations were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Mercer University School of Medicine and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The minimum possible number of animals (based on power analyses) was used for our experiments and steps were taken to minimize any suffering that might occur during our procedures.

2.2. Drugs and Chemicals

(±) METH hydrochloride was a generous gift from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD, USA). Ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Methamphetamine, ketamine and xylazine doses were calculated as the free base and dissolved in normal saline. All drugs were given in a volume of 1 ml/kg. Dermorphin-saporin (DERM-SAP) and unconjugated saporin (SAP) were obtained from Advanced Targeting Systems (San Diego, CA, USA) and dissolved in buffered artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 144 mM NaCl; 2.68 mM KCl; 1.6 mM CaCl2; 2.6 mM MgCl2; 0.4 mM KH2PO4, pH, 7.2).

2.3. DERM-SAP Infusion

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (90 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (9 mg/kg, i.p.) and fixed on a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting Company, Wood Dale, IL, USA). The skull was exposed and a burr hole was drilled through the skull in order to introduce a 29-gauge needle for the infusion. A total volume of 2 μl of DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl; (Tokuno et al., 2002) or the equivalent amount of unconjugated SAP (as a control; (Tokuno et al., 2002) was infused bilaterally into the rostral striatum (coordinates based on bregma: +1.7 mm anterior, 2.6 mm lateral, −5.0 mm ventral; (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) at a rate of 0.5 μl/min. The needle was left in place for five minutes following the infusion and slowly removed to minimize fluid backflow. The animals were then returned to their home cage, where they were allowed to survive for 8 days (Tokuno et al., 2002). Only animals whose infusions were in the rostral striatum were included in subsequent analyses.

2.4. Experimental Design and Behavior

Twenty-four hours prior to treatment with METH, animals were habituated to plexiglass activity chambers (46 × 46 × 12 cm on top of a 4 × 4 grid; (Frankel et al., 2007, Horner et al., 2012, Horner et al., 2010) by placing them in the chambers for 60 minutes, giving them sham injections and returning them to the chambers for 2h. The next day, animals were placed in the chambers for 60 minutes, after which time they were injected with METH (7.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline and returned to the activity chambers for 2h, during which time the behavior was digitally recorded for post-hoc analyses. During the post-hoc analyses, each animal's behavior was observed by an individual blind to the experimental conditions for 1 minute every 5 minutes for the entire 2h observation period after the injection of METH or saline. Stereotypy was rated on a scale of 1–10 (Table 1), with 10 representing the highest degree of the response (Canales and Graybiel, 2000, Horner et al., 2012, Horner et al., 2010). Stereotypy scores were generated by averaging the scores from four behavioral dimensions: repetitiveness/flexibility (the number of alternative motor responses emitted), frequency (the number of responses per unit time), duration (the percentage of time spent performing the most dominant response(s)) and the spatial distribution of the motor response (Canales and Graybiel, 2000). Locomotor activity was defined by the number of quadrants the animal crossed on the 4 × 4 grid, and was converted into centimeters (Frankel et al., 2007).

Table 1.

10-point stereotypy rating scale (adapted from Capper-Loup et al., 2002).

| 1 | Undetectable |

| 2 | Very weak |

| 3 | Weak |

| 4 | Weak-to-moderate |

| 5 | Moderate |

| 6 | Moderate-to-strong |

| 7 | Strong |

| 8 | Intense |

| 9 | Very intense |

| 10 | Extreme |

2.5. Tissue processing for immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Two hours (c-Fos) or three hours (zif/268 mRNA) after treatment with METH or saline, rats were sacrificed by exposure to CO2 for 1 minute followed by decapitation. The brains were rapidly harvested, quick-frozen in isopentane on dry ice and stored at −80°C until they were cut into 12-μm sections through the prefrontal cortex (at approximately +4.2 mm from bregma), striatum/nucleus accumbens (NAc; at approximately +1.7 mm from bregma), and substantia nigra (at approximately −5.25 mm from bregma; Paxinos and Watson, 2005) on a cryostat (Minotome Plus, Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, N.C., USA).

2.6. Mu opioid receptor immunohistochemistry

Sections through striatum were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.9% NaCl and then rinsed three times in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Slides were then blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/0.3% Triton X-100 (TX)/0.1 M PBS for 2 h followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody for the mu opioid receptor (Immunostar, Hudson, WI, USA), diluted in 1:1000 in 0.3% TX/0.1M PBS/5% BSA. The slides were then washed several times in PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted 1:200 in 0.1M PBS/5% BSA. Slides were then washed three times in PBS, incubated 1 h in ABC solution (Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) and washed three more times in PBS. Bound antibody was detected using a 3',3-diaminobenzidine/Ni+ solution (Vector Laboratories). Slides were washed with deionized H2O, dehydrated in a series of alcohols and coverslipped out of xylene.

2.6. c-Fos immunohistochemistry

Sections through prefrontal cortex, striatum/NAc and substantia nigra were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4 and then rinsed three times in PBS. Slides were then blocked with 4% normal goat serum (NGS)/0.3% TX for 1 h followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody for c-Fos (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), diluted in 1:1000 in 0.3% TX/0.1M PBS. The slides were then washed several times in PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:200 in 0.1M PBS/1% NGS. Slides were then washed three times in PBS, incubated 1 h in ABC solution (Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) and washed three more times in PBS. Bound antibody was detected using a 3',3-diaminobenzidine/Ni+ solution (Vector Laboratories). Slides were washed with deionized H2O, dehydrated in a series of alcohols and coverslipped out of xylene.

2.7. Calbindin immunohistochemistry

Sections through striatum were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4 and then rinsed three times in PBS. Slides were then blocked with 4% normal goat serum (NGS)/0.3% TX for 1 h followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody for calbindin (Immunostar), diluted in 1:1000 in 0.3% TX/0.1M PBS. The slides were then washed several times in PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:200 in 0.1M PBS/1% NGS. Slides were then washed three times in PBS, incubated 1 h in ABC solution (Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) and washed three more times in PBS. Bound antibody was detected using a 3',3-diaminobenzidine/Ni+ solution (Vector Laboratories). Slides were washed with deionized H2O, dehydrated in a series of alcohols and coverslipped out of xylene.

2.8. Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunohistochemistry

Sections through striatum were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.9% NaCl and then rinsed three times in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Slides were then blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/0.3% Triton X-100 (TX)/0.1 M PBS for 2 h followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody for ChAT (AbCam), diluted in 1:1000 in 0.3% TX/0.1M PBS/5% BSA. The slides were then washed several times in PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted 1:200 in 0.1M PBS/5% BSA. Slides were then washed three times in PBS, incubated 1 h in ABC solution (Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) and washed three more times in PBS. Bound antibody was detected using a 3',3-diaminobenzidine/Ni+ solution (Vector Laboratories). Slides were washed with deionized H2O, dehydrated in a series of alcohols and coverslipped out of xylene.

2.9. In situ hybridization histochemistry

Sections through prefrontal cortex were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.9% NaCl, acetylated in fresh 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine/0.9% NaCl (pH 8.0), dehydrated in alcohol, delipidated in chloroform and gradually re-hydrated in a descending series of alcohol concentrations. Slides were air-dried and stored at –20°C. An oligonucleotide probe (GeneDetect, Bradenton, FL, USA) complementary to bases 355–399 of zif/268 mRNA (Milbrandt, 1987) was end-labeled with [33P]-dATP (Perkin Elmer NEN, Wellesley, MA, USA). Each probe was diluted in hybridization buffer (0.6 M sodium chloride, 80 mM Tris, 4 mM EDTA, 0.1% w/v sodium pyrophosphate, 10% w/v dextran, 0.2% w/v lauryl sulfate, 0.5 mg/ml heparin, 50% formamide) and 90 μl of the probe in hybridization buffer was applied to each slide and covered with glass coverslips. Slides were hybridized overnight in humid chambers at 37°C, followed by four washes in 1× saline-sodium citrate (SSC; 0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.2) at room temperature and then three washes in 2× SSC with 50% (v/v) formamide at 42°C. Slides were washed twice in 1× SSC at room temperature, dipped in deionized H2O and air-dried. All labeled slides were apposed to X-ray film (Kodak Biomax MR film, Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY, USA) for approximately 30 days.

3.0. Image analysis

In order to confirm the loss of mu opioid receptor immunoreactive patches in the striatum, slides from mu opioid receptor immunohistochemistry were captured with a video camera (CCD IEEE-1394, Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA). Patches of mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity were outlined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), in both the left and right hemispheres for the whole rostral striatum (10–16 animals per treatment group), designated as the area below the corpus callosum and above the anterior commissure, ending approximately at the ventral tip of the lateral ventricle at approximately +1.7 mm anterior to bregma (see Fig. 1), and the number of patches in each hemisphere were counted and averaged. The number of mu-opioid receptor labeled patches that exceeded the threshold density was determined using the particle analysis option in ImageJ. Prior to analysis, the pixel range for patch size was determined by outlining approximately 5–15 positively labeled patches from 10–15 randomly selected sections and determining the average size of the labeled patches in terms of pixel area. The lower limit for a “labeled patch” on the particle analysis setting was then set to the smallest number of pixels measured for any patch, whereas the upper limit was set at the maximal particle size on the particle analysis option on ImageJ. The threshold density was adjusted such that background staining was eliminated and the number of mu-immunoreactive patches was measured above this threshold. In order to determine whether DERM-SAP treatment altered the overall size of the patch compartment, the total area, in pixels, of the mu-immunoreactive patches highlighted by thresholding in both the left and right hemispheres were averaged for each animal. Examination of the mean density of mu immunoreactive staining was also examined to confirm the loss of the patch compartment. Basic densitometric analysis yielded average density (gray) values over the region of interest. Before the measurement of sections, the linearity of the video camera to increasing signal intensity was determined using the average gray value of signals of known optical density from a photographic step tablet (Eastman Kodak Company). The intensity of the light was adjusted such that values from the mu opioid receptor immunoreactive sections fell within the linear portion of the system's response. Lighting and camera conditions remained constant during the process of capturing and collecting of density measurements. Regions containing mu opioid receptor staining were outlined using ImageJ software in the left and right hemispheres of the whole rostral striatum for each animal. The average gray value of the white matter overlying the striatum was subtracted from the average gray value of the region of interest to correct for background labeling in the left and right hemispheres and averaged for each animal.

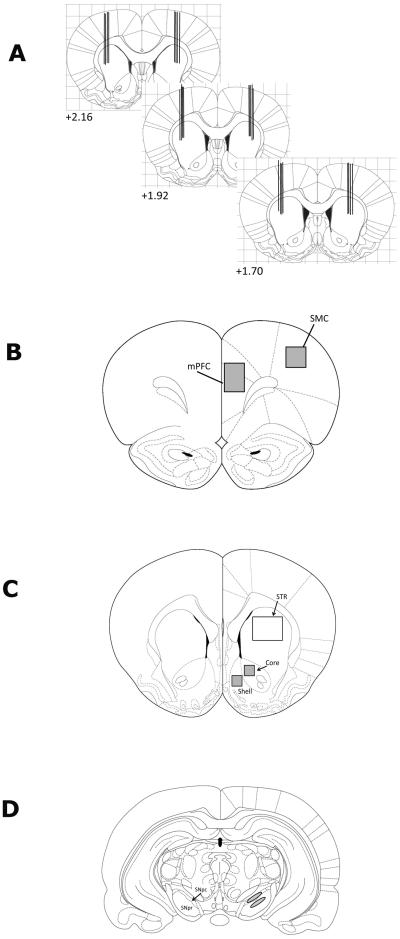

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the approximate location of the microinjection cannulae tips (A) and the sub-regions used for semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos and ChAT immunoreactivity (B–D). Measurements are given relative to bregma. The regions used for particle analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity are highlighted in gray and consist of the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor cortices (+4.52 mm), core and shell of NAc (+ 1.7 mm) and SNpc and SNpr (−5.25 mm), while the region of striatum (+1.7 mm) used for particle analysis of ChAT immunoreactivity is unshaded. Abbreviations: mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; SMC, sensorimotor cortex; STR, striatum, SNpc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNpr, substantia nigra pars reticulata.

Calbindin, which is preferentially expressed in the matrix versus the patch compartment (Gerfen et al., 1985), was immunohistochemically labeled in order to confirm that the matrix compartment was intact following DERM-SAP pretreatment. Slides from calbindin immunohistochemistry were captured with a video camera (CCD IEEE-1394, Scion Corporation). Basic densitometric analysis yielded average density (gray) values over the region of interest, and the imaging parameters were determined as described above for mean density measurement of mu opioid receptor staining. Regions containing calbindin staining were outlined using ImageJ software in the left and right hemispheres of the whole rostral striatum for each animal. The average gray value of the white matter overlying the striatum was subtracted from the average gray value of the region of interest to correct for background labeling in the left and right hemispheres and averaged for each animal. In addition, the total area of the calbindin-labeled region of interest in both the left and right hemispheres was determined using ImageJ and averaged for each animal.

Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunohistochemistry was utilized in order to determine whether cholinergic interneurons, a sub-population of which express mu opioid receptors (Jabourian et al. , 2005), were affected by DERM-SAP treatment. ChAT-labeled images (10–16 animals per treatment group) were captured from a VistaVision microscope (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) with a video camera (CCD Moticam 2300, Motic, Richmond, BC, Canada), using a 10× objective. Immunoreactivity was measured in a 1024 × 768 pixel square encompassing the left dorsal striatum (Fig. 1) and was based on previously described procedures (Choe et al. , 2002, Horner et al. , 2011, Horner et al., 2006, Simpson et al., 1995). The number of ChAT-labeled particles that exceeded the threshold density in each region of interest was determined using the particle analysis option in ImageJ. Prior to analysis, the pixel range for particle size was determined by outlining approximately 15–20 positively labeled cells from 10–15 randomly selected sections and determining the average size of the labeled cells in terms of pixel area. The lower limit for a “labeled cell” on the particle analysis setting was then set to the smallest number of pixels measured for any cell, whereas the upper limit was set at the maximal particle size on the particle analysis option on ImageJ. The threshold density was adjusted such that background staining was eliminated and the number of immunoreactive pixels per the selected area in each region of interest was measured above this threshold.

Pixel range determination and particle analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity was performed as described above for ChAT. Briefly, images from the left hemisphere (5–8 animals per treatment group) were captured from a VistaVision microscope (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) with a video camera (CCD Moticam 2300), using a 10× objective and c-Fos immunoreactivity measured in a 500 × 500 pixel square for the sensorimotor sub-region of prefrontal cortex, a 500 × 600 pixel rectangle for the medial prefrontal cortex, a 400 × 400 pixel square the core and shell of the NAc, and a 500 × 150 pixel oval for the substantia nigra pars compacta and pars reticulata (Fig. 1).

Sections adjacent to those used for c-Fos immunohistochemistry were labeled for calbindin immunohistochemistry in order to distinguish the patch and matrix compartments of striatum. Both c-Fos-labeled sections and adjacent calbindin-labeled sections from the left hemisphere were captured on a VistaVision (VWR) microscope with a video camera (CCD Moticam 2300) using a 2.5× objective. Image J was used to outline regions of either dense calbindin immunoreactivity (matrix) or absent calbindin immunoreactivity (patch) and which were superimposed over corresponding areas of the adjacent c-Fos-labeled striatal section and the number c-Fos-labeled particles counted in the region of interest, as described above. Counts of c-Fos-labeled particles were expressed as the number c-Fos-ir particles per mm2.

For the analysis of zif/268 mRNA expression, film autoradiograms were analyzed using the image analysis program ImageJ, as previously described (Horner et al., 2012, Horner and Keefe, 2006). Zif/268-labeled autoradiographic films were from captured with a video camera (CCD IEEE-1394, Scion Corporation) and basic densitometric analysis yielded average density (gray) values over regions of interest, as described above for the analysis of mu opioid receptor and calbindin immunoreactivity. Images from the left prefrontal cortex from 5 to 8 animals per treatment group were analyzed for each region of interest examined. Measurements were made according to the coordinates of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) in the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor cortices. The average gray value of the white matter overlying the structure being measured was subtracted from the average gray value of the region of interest to correct for background labeling.

3.1. Statistical analysis

A student's t-test was used to analyze the effects of DERM-SAP treatment the number and total area of mu opioid receptor labeled patches, the density of calbindin staining and the number of ChAT immunoreactive particles in the striatum. The effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity and zif/268 mRNA expression were analyzed using a two-way (pretreatment × treatment) analysis of variance for each region of interest. Behavioral rating data was represented as the area under the curve (AUC) and was also analyzed using a two-way (pretreatment × treatment) analysis of variance. Post-hoc analysis of significant effects was accomplished using Tukey multicomparison tests. The alpha level for all analyses was set at 0.05.

3. Results

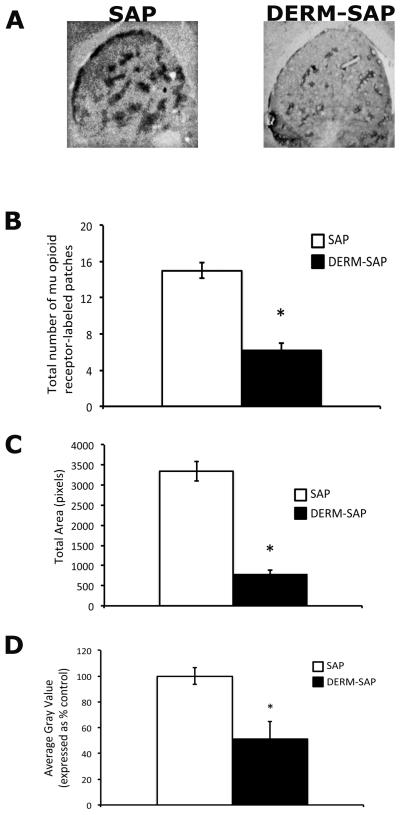

3.1. Effects of DERM-SAP infusion on mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the striatum

Infusion of DERM-SAP into striatum reduced mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity relative to infusion of unconjugated SAP (Fig. 2A). A student's t-test revealed that DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly reduced the number of mu opioid receptor-labeled patches in the striatum (t = 8.0, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2B). An unpaired t-test also revealed that DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly reduced the total area of patches present in the striatum (t = 9.8, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2C), as well as the mean density of mu opioid receptor immunoreactive staining (t=5.108, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Effects of DERM-SAP infusion on mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the striatum. Infusion with the neurotoxin DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl) resulted in a decrease in mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the striatum (A). DERM-SAP treatment significantly reduced the overall number of mu-labeled patches in the striatum (B), the total size of mu opioid receptor immunoreactive patches (C), and the mean density of mu opioid receptor immunoreactive staining (D), as compared to animals treated with unconjugated SAP. *p<0.05 vs. SAP-treated control animals.

3.2. Effects of DERM-SAP infusion on calbinin immunoreactivity in the striatum

An unpaired t-test revealed that infusion of DERM-SAP into striatum did not significantly alter the mean density of calbindin immunoreactive staining relative to animals infused with unconjugated SAP (t = .5110, p = .6160, data not shown). Infusion of DERM-SAP into striatum also did not significantly alter the total area of calbindin immunoreactivity relative to SAP-infused animals (t = .5526, p = .5877).

3.3. Effects of DERM-SAP infusion on ChAT immunoreactivity in the striatum

An unpaired t-test revealed that infusion of DERM-SAP into striatum did not significantly alter the number of ChAT-immunoreactive particles relative to animals infused with unconjugated SAP (t = .3160, p = .7547, data not shown).

3.4. Effects of intrastriatal infusion of DERM-SAP on METH-induced behaviors

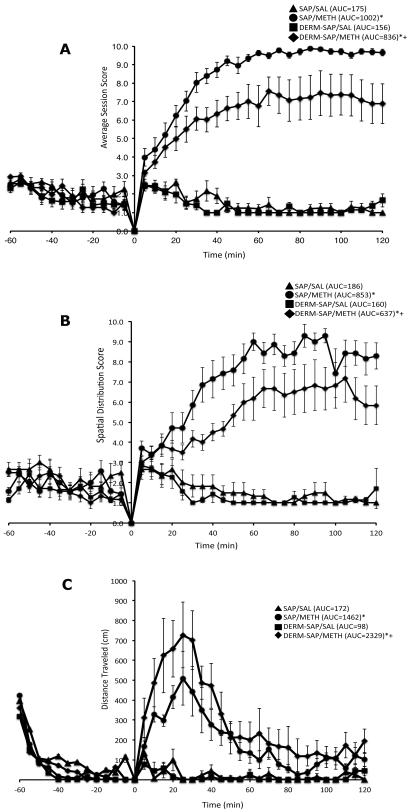

Acute treatment of METH initially resulted in a period of markedly increased locomotor activity for the first 40–50 minutes after treatment which was then followed by a sustained period of markedly increased stereotyped behavior and spatial confinement (Fig. 3A–C).

Figure 3.

Effects of intrastriatal infusion of DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl) and methamphetamine treatment (7.5 mg/kg) on stereotyped behavior (A), spatial confinement (B) and locomotor activity (C). Values are expression as the mean ±SEM. AUC values are in parentheses. *Significantly different from respective control group, p<0.005; +Significantly different from SAP-pretreated METH-treated group, p<0.005.

A two-way analysis of variance of the AUC values for stereotyped behavior scores during the two hour observation period revealed a significant main effect for DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,22 = 10.81, p = 0.0034), METH treatment (F1,22 = 713.0, p < 0.0001), and a significant interaction of pretreatment × treatment (F1,22 = 6.853, p = 0.0157). Post-hoc analysis revealed that METH treatment significantly increased stereotyped behavior in both SAP (p < 0.05) and DERM-SAP (p < 0.05) pretreated animals; however, the METH-induced increase in stereotyped behavior was significantly lower in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals than in SAP-pretreated animals (p < 0.05). DERM-SAP pretreatment alone did not significantly affect stereotyped behavior in saline-treated animals (p > 0.05).

A two-way analysis of variance of the AUC values for spatial confinement scores during the two hour observation period revealed a significant main effect for DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,22 = 8.668, p = 0.0075), METH treatment (F1,22 = 194.4, p < 0.0001), and a significant interaction of pretreatment × treatment (F1,22 = 5.357, p = 0.0304). Post-hoc analysis revealed that METH treatment significantly increased spatial confinement in both SAP (p < 0.05) and DERM-SAP (p < 0.05) pretreated animals; however, the METH-induced increase in spatial confinement was significantly lower in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals than in SAP-pretreated animals (p < 0.05). DERM-SAP pretreatment alone did not significantly affect spatial confinement in saline-treated animals (p > 0.05).

A two-way analysis of variance of the AUC values for locomotor activity scores during the two hour observation period revealed a significant main effect for DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,22 = 4.520, p = 0.0450), METH treatment (F1,22 = 89.17, p < 0.0001), and a significant interaction of pretreatment × treatment (F1,22 = 6.360, p = 0.0194). Post-hoc analysis revealed that METH treatment significantly increased locomotor activity in both SAP (p < 0.05) and DERM-SAP (p < 0.05) pretreated animals; however, the METH-induced increase in locomotor activity was significantly greater in DERM-SAP pretreated animals than in SAP-pretreated animals (p < 0.05). DERM-SAP pretreatment alone did not significantly affect horizontal activity in saline-treated animals (p > 0.05).

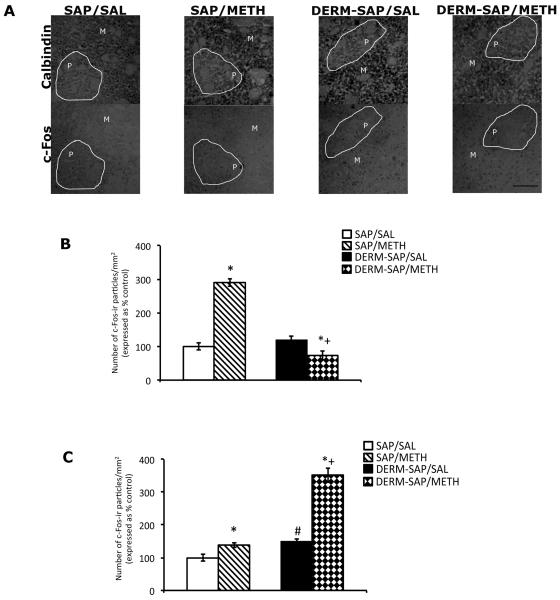

3.4 Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the patch and matrix compartments of striatum

Ablation of the patch compartment appeared to prevent METH-induced increases in c-Fos immunoreactive particles in the patch compartment of the striatum, but enhanced METH-induced increases in c-Fos immunoreactive particles in the matrix of the striatum (Fig. 4A). Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the patch compartment of the striatum, followed by a two-way analysis of variance revealed significant main effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,18 = 27.44, p < .0001), METH treatment (F1,18 = 14.48, p = .0013), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,18 = 35.87, p < .0001; Fig. 4B). Post-hoc analyses revealed that in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, METH treatment did not significantly increase the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the patch compartment, relative to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p > 0.05), and that in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, there were significantly fewer c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the patch compartment following METH treatment, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH-treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment significantly increased the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the patch compartment of SAP-pretreated animals (p < 0.05), and DERM-SAP pretreatment alone did not significantly alter the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the patch compartment (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced immunoreactivity in the patch and matrix compartments of striatum. Representative photomicrographs showing calbindin and c-Fos immunoreactivity in adjacent sections of the striatum (A). Scale bar represents 100 μM. Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the patch (B) and matrix (C) compartments of rats intrastriatally infused with SAP or DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl), 8 days prior to treatment with METH (7.5 mg/kg). Data are presented as the percentage of the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in SAP-treated control animals. *p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated control animals; +p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated METH-treated animals; #p<0.05 vs. DERM-SAP-pretreated control animals.

Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the matrix of the striatum, followed by a two-way analysis of variance revealed significant main effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,16 = 13.58, p = .0020), METH treatment (F1,16 = 11.08, p = .0043), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,16 = 5.372, p = .0340; Fig. 4C). Post-hoc analyses revealed that METH treatment significantly increased the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the matrix compartment of DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p < 0.05), and that METH treatment significantly increased the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the matrix of DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment significantly increased the number of c-Fos immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the matrix compartment of SAP-pretreated animals (p < 0.05), and DERM-SAP pretreatment alone significantly increased the number of c-Fos-immunoreactive particles/mm2 in the matrix compartment (p < 0.05).

3.5. Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the NAc

Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the NAc core revealed a significant main effect for METH treatment (F1,19 = 29.82, p < .0001) but not a significant main effect for DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,19 = .1374, p = .7150) or pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,19 = 3.103, p = .0942; data not shown). Post-hoc analysis revealed that METH treatment significantly increased NAc core c-Fos immunoreactivity (p < 0.05). Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the NAc shell revealed a significant main effect for METH treatment (F1,19 = 36.61, p < .0001) but not a significant main effect for DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,19 = .1154, p = .7378) or a pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,19 = 4.192, p = .0547; data not shown). Post-hoc analysis revealed that METH treatment significantly increased NAc shell c-Fos immunoreactivity (p < 0.05).

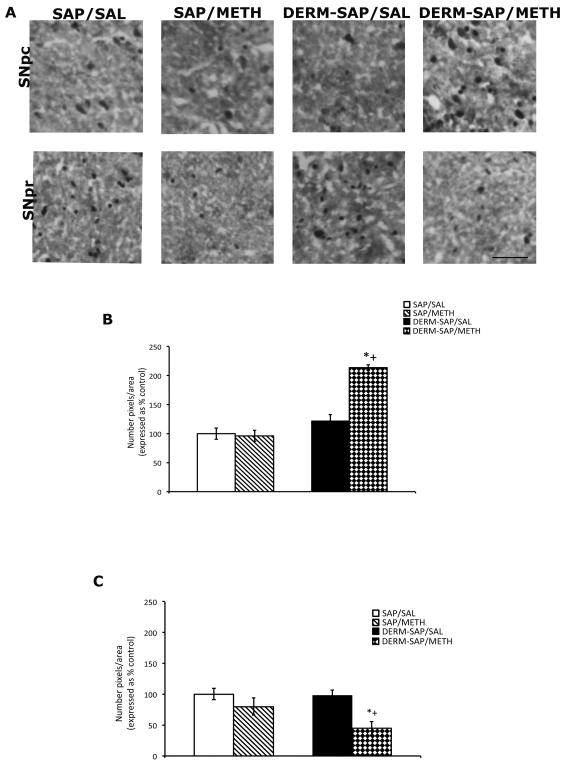

3.6. Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra

Administration of METH following the partial ablation of the patch compartment appeared to increase c-Fos immunoreactive particles in the SNpc, but decrease c-Fos immunoreactive particles in the SNpr (Fig. 5A). Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SNpc, followed by a two-way analysis of variance revealed significant main effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,16 = 39, p <0.0001), METH treatment (F1,16 = 16, p = 0.0011), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,16 = 18, p = 0.0006; Fig. 5B). Post-hoc analyses revealed that METH treatment significantly increased SNpc c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p < 0.05) and that METH treatment significantly increased SNpc c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH-treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment did not have a significant effect on SNpc c-Fos immunoreactivity in SAP-pretreated animals (p > 0.05), nor did DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly alter c-Fos immunoreactivity in saline-treated animals (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra. Photomicrographs showing c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SNpc and SNpr (A). Scale bar represents 100 μM. Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SNpc (B) and SNpr (C) in rats intrastriatally infused with SAP or DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl), 8 days prior to treatment with METH (7.5 mg/kg). Data are presented as the percentage of c-Fos immunoreactive particles in SAP-treated control animals. *p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated control animals; +p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated METH-treated animals.

Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SNpr, followed by a two-way analysis of variance revealed significant main effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,15 =8, p=0.013), METH treatment (F1,15 = 32, p <0.0001), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,15 = 6.5, p = 0.02; Fig. 5C). Post-hoc analyses revealed that METH treatment significantly decreased SNpr c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p < 0.05) and that METH treatment significantly decreased SNpr c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH-treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment did not have a significant effect on SNpr c-Fos immunoreactivity in SAP-pretreated animals (p > 0.05), nor did DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly alter basal c-Fos immunoreactivity (p > 0.05). In addition, since the intensity of the c-Fos-labeled cells in the SNpr appeared to be reduced to a similar extent in METH-treated animals that were pretreated with either SAP or DERM-SAP, we examined the mean density of c-Fos-labeled cells in the SNpr. Two-way analysis of variance of mean density values of c-Fos labeled cells in the SNpr revealed no significant effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,17 =0.232, p=0.50), METH treatment (F1,17 =0.60, p=0.50), nor was there a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,17 =0.53, p=0.64).

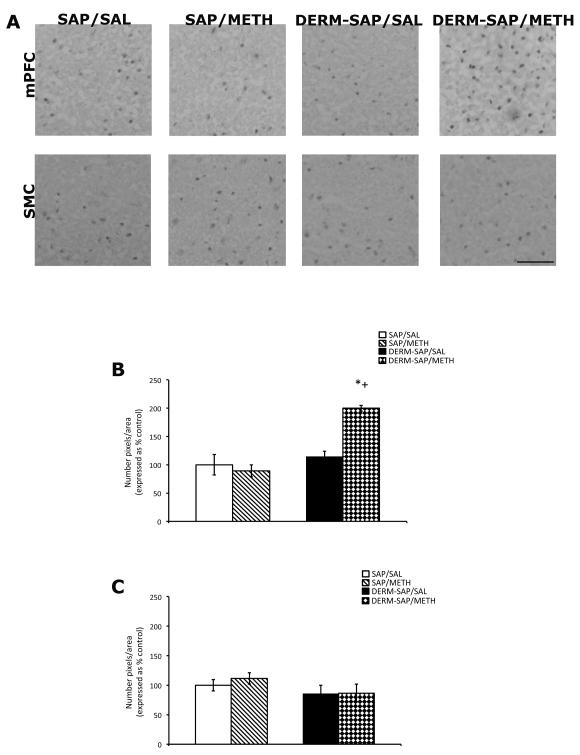

3.4. Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor cortices

Administration of METH following the partial ablation of the patch compartment appeared to increase c-Fos immunoreactive particles in medial prefrontal, but not sensorimotor cortex (Fig. 6A). Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex, followed by a two-way analysis of variance revealed a significant main effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,19 = 26, p <0.0001), METH treatment (F1,19 = 9.1, p = 0.007), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,19 = 15, p = 0.001; Fig. 6B). Post-hoc analyses revealed that METH treatment significantly increased medial prefrontal c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p < 0.05) and that METH treatment significantly increased medial prefrontal c-Fos immunoreactivity in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH-treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment did not have a significant effect on medial prefrontal c-Fos immunoreactivity in SAP-pretreated animals (p > 0.05), nor did DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly alter c-Fos immunoreactivity in saline-treated animals (p > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in the frontal cortex. Photomicrographs showing c-Fos immunoreactivity in the mPFC and SMC (A). Scale bar represents 100 μM. Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the mPFC (B) and SMC (C) in rats intrastriatally infused with SAP or DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl), 8 days prior to treatment with METH (7.5 mg/kg). Data are presented as the percentage of c-Fos immunoreactive particles in SAP-treated control animals. *p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated control animals; +p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated METH-treated animals.

Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the sensorimotor sub-region of frontal cortex, followed by a two-way analysis of variance did not reveal a significant effect of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,19=2.83, p=0.110), METH treatment (F1,19=0.424, p=0.530) or a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,19=1.683, p=0.686), nor did DERM-SAP pretreatment alter basal c-Fos immunoreactivity in this region (Fig. 6C).

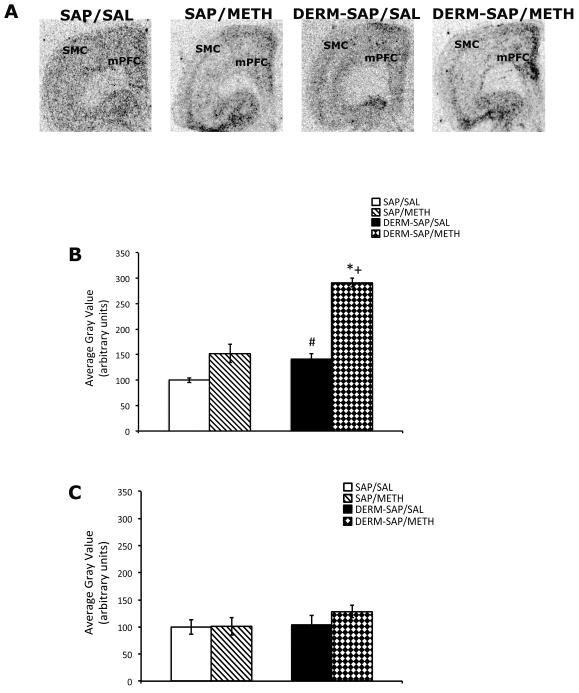

3.5. Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced zif/268 mRNA expression in the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor cortices

Administration of METH following the partial ablation of the patch compartment appeared to increase zif/268 mRNA expression in medial prefrontal, but not sensorimotor cortex (Fig. 7A). Two-way analysis of the effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced zif/268 mRNA expression in the medial prefrontal cortex revealed a significant main effect of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,18 = 19.25, p <0.0004), METH treatment (F1,18 = 24.2, p = 0.0001), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,12 = 5.68, p = 0.03; Fig. 7B). Post-hoc analyses revealed that METH treatment significantly increased medial prefrontal zif/268 mRNA expression in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to DERM-SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals (p < 0.05) and that METH treatment significantly increased medial prefrontal zif/268 mRNA expression in DERM-SAP-pretreated animals, as compared to SAP-pretreated, METH-treated animals (p < 0.05). METH treatment did not have a significant effect on medial prefrontal zif/268 mRNA expression in SAP pretreated animals (p > 0.05); however, DERM-SAP pretreatment significantly increased basal zif/268 expression (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on METH-induced zif/268 mRNA expression in the frontal cortex. Film autoradiograms showing zif/268 mRNA expression in the mPFC and SMC (A). Quantitative analysis of zif/268 mRNA expression in the mPFC (B) and SMC (C) of rats intrastriatally infused with SAP or DERM-SAP (17 ng/μl), 8 days prior to treatment with METH (7.5 mg/kg). Data are presented as the percentage of zif/268 mRNA expression in SAP-treated control animals. *p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated control animals; +p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated METH-treated animals; # p<0.05 vs. SAP-pretreated, saline-treated animals.

Two-way analysis of variance of the effects of DERM-SAP pretreatment on zif/268 mRNA expression in the sensorimotor sub-region of frontal cortex did not reveal a significant effect of DERM-SAP pretreatment (F1,18=1.04, p=0.320), METH treatment (F1,19=0.658, p=0.427) or a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F1,19=0.597, p=0.449), nor did DERM-SAP pretreatment alter basal zif/268 mRNA expression in this region (Fig. 7C).

4. Discussion

The goal of the current study was to determine whether perturbation of the patch compartment would have an impact on METH-induced behaviors and alter immediate early gene expression in the striatum, substantia nigra, and frontal cortex in response to METH treatment. Intrastriatal infusion of the neurotoxin DERM-SAP resulted in a 60–70% reduction in the size, total area and mean density of mu opioid receptor-labeled patches in the striatum. Lesions of the patch compartment resulted in a significant decrease in METH-induced stereotypic behavior and spatial confinement, while significantly increasing horizontal activity in response to METH treatment. Ablation of the patch compartment prevented induction of c-Fos by METH in this region, and enhanced METH-induced c-Fos expression in the matrix compartment of striatum. In addition, ablation of the patch compartment enhanced METH-induced c-Fos expression in the SNpc, while diminishing METH-induced c-Fos expression in the SNpr. Finally, destruction of the patch compartment potentiated METH-induced c-Fos and zif/268 mRNA expression in medial prefrontal, but not sensorimotor cortex. These data are among the first to specifically demonstrate a role for the patch compartment in the development of METH-induced stereotypy, indicating that preferential activation of the patch-based limbic circuits that traverse the striatum is necessary for the development of intense and focused repetitive behaviors, which is in contrast with the notion that enhanced activation of the patch compartment may serve as a homeostatic mechanism to counteract overstimulation of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons by psychostimulants and dampen stereotypic behaviors (Canales, 2005, Saka and Graybiel, 2003). Furthermore, these data suggest that the patch compartment may provide a node of contact between the limbic system and basal ganglia, whereby internally-driven states can modify and influence the motoric and adaptive behavioral functions mediated by the basal ganglia.

Previous studies indicate that treatments that result in a high level of stereotypy also induce greater relative activation of the patch compartment versus the matrix compartment, while treatments that induce a low level of stereotypy result in relatively similar levels of activation in the two compartments (Adams et al., 2003, Canales and Graybiel, 2000, Graybiel et al., 1990, Horner et al., 2012, Horner et al., 2010). On the other hand, sensorimotor stimulation or free movement is associated with increased activation of the matrix compartment (Brown et al., 2002, White and Hiroi, 1998) and increased activation of the direct pathway, which arises primarily from the matrix compartment, contributes to the expression of psychostimulant-induced hyperlocomotor activity (Crittenden and Graybiel, 2011, Fujiyama et al., 2011, Gerfen and Young, 1988, Nestler, 2001, Tokuno et al., 2002, Xu et al., 2000, Xu et al., 1994). Furthermore, the expression of stereotypy is thought to compete with locomotor activity (Aliane et al., 2009, Canales and Graybiel, 2000). Our data show that lesions of the patch compartment prior to METH treatment resulted in enhanced activation of matrix compartment, which was associated with increased locomotor activity and diminished stereotypy in METH-treated animals. In terms of how increased activity in the matrix compartment might relate to METH-induced changes in behavior, when the patch compartment is fully intact the effects of the activation of matrix-based pathways may be masked by the relatively greater activation of patch-based circuits, resulting in greater levels of stereotypy as compared to locomotor activity. On the other hand, when the patch compartment is compromised, the balance of activity tips in favor of the matrix compartment following METH treatment, leading to a greater degree of activation of the direct pathway, and increased locomotor activity.

Destruction of the patch compartment and enhanced activity of the matrix compartment following METH treatment may have also contributed to the METH-induced changes in c-Fos expression in the substantia nigra. The medium spiny neurons originating in the patch compartment send GABAergic projections to the dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc (Bolam and Smith, 1990, Fujiyama et al., 2011, Gerfen, 1984, Jimenez-Castellanos and Graybiel, 1989, Tokuno et al., 2002) and electrical stimulation of the striatum has been shown to result in a monosynaptic inhibition of these neurons (Collingridge and Davies, 1981, Grace and Bunney, 1985, Paladini and Tepper, 1999, Tepper et al., 1990). Thus, it is possible that ablation of the patch compartment resulted in decreased inhibitory influence on the dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc, and may have also unmasked excitatory inputs to the SNpc, such as those from the lateral hypothalamus (Houk et al., 1995, Joel et al., 2002), leading to enhanced c-Fos immunoreactivity in this region following METH treatment. The SNpr, on the other hand, receives GABAergic striatal inputs from the medium spiny neurons of the direct pathway (Albin et al., 1989, DeLong, 1990, Gerfen and Wilson, 1996). Thus, the reduction in c-Fos immunoreactivity observed in patch-lesioned animals in the SNpr following METH treatment could reflect an increase in GABAergic striatonigral transmission, as a result of increased activation of the matrix-based direct pathway.

Immediate early genes, such as c-fos and zif/268, typically serve as indicators of neuronal activation, but also encode transcription factors that mediate the activity of other genes and are thought to be involved in neuronal plasticity, particularly the neural adaptations that occur following drug exposure (Cole et al., 1995, Knapska and Kaczmarek, 2004, Unal et al., 2009, Valjent et al., 2006). In animals treated with METH, pretreatment with DERM-SAP significantly increased both c-Fos immunoreactivity and zif/268 mRNA expression in the medial prefrontal cortex, but not the sensorimotor cortex. It is possible that enhanced METH-induced gene expression in medial prefrontal, but not sensorimotor cortex following patch compartment lesions reflects an imbalance in activity in additional basal ganglia circuits. Superimposed upon the patch and matrix compartments, is a medial-to-lateral topography of circuits that transverse the striatum as a whole. Specifically, circuits that transverse the dorsolateral striatum are thought to transfer sensorimotor information through the basal ganglia, while the circuits that transverse the dorsomedial striatum are thought to transfer limbic-related information through the basal ganglia (Gerfen, 1989, 1992, Voorn et al., 2004). Interestingly, recent data indicates that during the expression of psychostimulant-induced stereotypy, there was a loss of information transmission through the limbic-related circuits that transverse the dorsomedial striatum, while information transmission through the sensorimotor circuits that transverse the dorsolateral striatum were unaltered, resulting in an imbalance in activity between the two circuits (Aliane et al., 2009). Since these sensorimotor and limbic-related loops through the striatum originate, and may also terminate, in the sensorimotor and medial prefrontal cortices (Alexander et al., 1986, Gerfen and Wilson, 1996, Kelly and Strick, 2004), it is possible that the increased immediate early gene expression in the medial prefrontal cortex, relative to the sensorimotor cortex could be the result of the recovery of information transmission within the medial prefrontal/dorsomedial striatal circuit, which may be associated with reduced stereotypic behavior in DERM-SAP pre-treated, METH-treated animals.

It is important to note that although our lesions were targeted to mu opioid receptor-expressing neurons of the patch compartment (Herkenham and Pert, 1981, Pert et al., 1976, Tempel and Zukin, 1987), a very small portion of mu opioid receptors exist on the medium spiny neurons of the matrix compartment (Guttenberg et al., 1996, Kaneko et al., 1995), as well as on a subset of cholinergic interneurons (Jabourian et al., 2005), raising the possibility that regions outside of the patch compartment may have been compromised by DERM-SAP treatment. However, our data indicate that both the matrix compartment and cholinergic interneurons were unaffected, as there was no decrease in calbindin or ChAT immunoreactivity following DERM-SAP treatment, which is in line with previous work (Lawhorn et al., 2009). It is also important to keep in mind that following DERM-SAP treatment, roughly 30% of mu opioid receptor-labeled patches remained intact, which could explain why we failed to see a complete abolishment of METH-induced stereotypy. Furthermore, the fact that a certain degree of METH-induced stereotypy remained following perturbation of the patch compartment points to a potential contribution of extrastriatal regions such as the pedunculopontine nucleus or subthalamic nucleus to psychostimulant-induced stereotypic behavior (Aliane et al., 2012, Barwick et al., 2000, Inglis et al., 1994, Mathur et al., 1997, Pallanti et al., 2010). In addition, since our techniques involved one-dimensional analyses of patch density and utilized mean density of mu opioid receptor immunohistochemical staining rather than quantifying cell counts to determine the degree of patch destruction, it is possible that we were not able to fully detect the effects of DERM-SAP treatment on the patch compartment. Nevertheless, despite these potential limitations, these are among the data first to specifically examine the role of the patch compartment in METH-induced behavior and gene expression.

It is also important to note that in our hands, METH treatment alone did not significantly alter gene expression in either the substantia nigra or medial prefrontal cortex. These data are in conflict with previous studies where acute METH treatment increased immediate early gene expression in both of these regions (Gross and Marshall, 2009, Ishida et al., 1998a, Ishida et al., 1998b, Shilling et al., 2006, Thiriet et al., 2001, Wang and McGinty, 1995, Wang et al., 1995). The reason for this discrepancy is not clear, but it could be that the dose of METH used in the current study was not high enough to produce a robust increase in gene expression, or that gene expression may have begun to wane in by the 2 h post-treatment time point utilized in our study. However, this was not a global effect, as our data showed that c-Fos expression in the striatum was significantly increased 2 h post-METH treatment. Alternatively, since gene expression in the substantia nigra and medial prefrontal cortex was not significantly altered following exposure to a dose of METH that induces stereotypy, these regions may not directly contribute to the genesis of stereotypic behavior, while the patch compartment, which shows robust activation during METH-induced stereotypy, contributes more heavily to the expression of psychostimulant-induced repetitive behaviors. On the other hand, when the activity of patch-based circuits in the striatum are diminished, this may result in downstream changes in the activity of these regions in response to METH treatment that represents the effect of altering overall striatal output rather than reflecting the role that the substantia nigra and prefrontal cortex play in the development of repetitive behaviors.

In summary, our study is among the first to use a targeted neurotoxin to specifically lesion the patch compartment to elucidate the role of this region in the development of METH-induced stereotyped behaviors. The current data demonstrate that the patch compartment must be intact in order for maximal expression of stereotypy in response to a single, high dose of METH, indicating that activation of limbic-associated, patch-based circuits contributes to psychostimulant-induced repetitive behaviors. Lesions of the patch compartment also increased METH-induced locomotor activity and augmented METH-induced activation of the matrix compartment, indicating that in the absence of enhanced activation of the patch compartment, the matrix-based circuits that mediate locomotor activity are unmasked, resulting in decreased spatial confinement and augmented locomotor activity. Finally, lesions of the patch compartment altered immediate early gene expression in the substantia nigra and prefrontal cortex, suggesting that patch-based circuits may influence striatal output, which results in downstream changes in activity in the basal ganglia and associated regions. Together, these data indicate that the patch compartment is an important component of the basal ganglia circuitry that mediates repetitive behaviors, and suggests that when the activity of this region is enhanced as a result of METH exposure, internally-driven motivational states may override ongoing adaptive behaviors, leading to focused stereotypy and possibly maladaptive habitual behaviors.

Abbreviations

- DERM-SAP

Dermorphin-saporin

- SAP

unconjugated saporin

- METH

methamphetamine

- SAL

saline

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- SMC

sensorimotor cortex

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SNpr

substantia nigra pars reticulata

References

- Adams DH, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Distinct effects of methamphetamine and cocaine on preprodynorphin messenger RNA in rat striatal patch and matrix. J Neurochem. 2003;84:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliane V, Perez S, Deniau JM, Kemel ML. Raclopride or high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus stops cocaine-induced motor stereotypy and restores related alterations in prefrontal basal ganglia circuits. The European journal of neuroscience. 2012;36:3235–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliane V, Perez S, Nieoullon A, Deniau JM, Kemel ML. Cocaine-induced stereotypy is linked to an imbalance between the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor circuits of the basal ganglia. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barwick VS, Jones DH, Richter JT, Hicks PB, Young KA. Subthalamic nucleus microinjections of 5-HT2 receptor antagonists suppress stereotypy in rats. Neuroreport. 2000;11:267–70. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Izzo PN, Graybiel AM. Cellular substrate of the histochemically defined striosome and matrix system of the caudate nucleus: a combined golgi and immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 1988;24:853–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Smith Y. The GABA and substance P input to dopaminergic neurones in the substantia nigra of the rat. Brain Res. 1990;529:57–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90811-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LL, Feldman SM, Smith DM, Cavanaugh JR, Ackermann RF, Graybiel AM. Differential metabolic activity in the striosome and matrix compartments of the rat striatum during natural behaviors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:305–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales JJ. Stimulant-induced adaptations in neostriatal matrix and striosome systems: transiting from instrumental responding to habitual behavior in drug addiction. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;83:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales JJ, Graybiel AM. A measure of striatal function predicts motor stereotypy. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:377–83. doi: 10.1038/73949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe ES, Chung KT, Mao L, Wang JQ. Amphetamine increases phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and transcription factors in the rat striatum via group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:565–75. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00341-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RL, Konradi C, Douglass J, Hyman SE. Neuronal adaptation to amphetamine and dopamine: molecular mechanisms of prodynorphin gene regulation in rat striatum. Neuron. 1995;14:813–23. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Davies J. The influence of striatal stimulation and putative neurotransmitters on identified neurones in the rat substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1981;212:345–59. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden JR, Graybiel AM. Basal Ganglia disorders associated with imbalances in the striatal striosome and matrix compartments. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:59. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:281–5. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90110-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagergren P, Smith HR, Daunais JB, Nader MA, Porrino LJ, Hurd YL. Temporal upregulation of prodynorphin mRNA in the primate striatum after cocaine self-administration. The European journal of neuroscience. 2003;17:2212–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel PS, Hoonakker AJ, Danaceau JP, Hanson GR. Mechanism of an exaggerated locomotor response to a low-dose challenge of methamphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:511–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama F, Sohn J, Nakano T, Furuta T, Nakamura KC, Matsuda W, et al. Exclusive and common targets of neostriatofugal projections of rat striosome neurons: a single neuron-tracing study using a viral vector. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:668–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: compartmentalization of corticostriatal input and striatonigral output systems. Nature. 1984;311:461–4. doi: 10.1038/311461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: striatal patch-matrix organization is related to cortical lamination. Science. 1989;246:385–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2799392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:133–9. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90355-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Baimbridge KG, Miller JJ. The neostriatal mosaic: compartmental distribution of calcium-binding protein and parvalbumin in the basal ganglia of the rat and monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8780–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Wilson CJ. The Basal Ganglia. In: Swanson LW, Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Elsevier Sciences; Amsterdam: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Young WS., 3rd Distribution of striatonigral and striatopallidal peptidergic neurons in both patch and matrix compartments: an in situ hybridization histochemistry and fluorescent retrograde tracing study. Brain Res. 1988;460:161–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giagnoni G, Parolaro D, Casiraghi L, Crema G, Sala M, Andreis C, et al. Dermorphin interaction with peripheral opioid receptors. Neuropeptides. 1984;5:157–60. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(84)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. Opposing effects of striatonigral feedback pathways on midbrain dopamine cell activity. Brain Res. 1985;333:271–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators in the basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:244–54. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90104-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Moratalla R, Robertson HA. Amphetamine and cocaine induce drug-specific activation of the c-fos gene in striosome-matrix compartments and limbic subdivisions of the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6912–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Rausch SL. Toward a neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuron. 2000;28:343–7. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross NB, Marshall JF. Striatal dopamine and glutamate receptors modulate methamphetamine-induced cortical Fos expression. Neuroscience. 2009;161:1114–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttenberg ND, Klop H, Minami M, Satoh M, Voorn P. Co-localization of mu opioid receptor is greater with dynorphin than enkephalin in rat striatum. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2119–24. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199609020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Pert CB. Mosaic distibution of opiate receptors, parafascilular projections and acetylcholinesterase in rat striatum. Nature. 1981;291:415–8. doi: 10.1038/291415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KA, Gilbert YE, Cline SD. Widespread increases in malondialdehyde immunoreactivity in dopamine-rich and dopamine-poor regions of rat brain following multiple, high doses of methamphetamine. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:27. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KA, Hebbard JC, Logan AS, Vanchipurakel GA, Gilbert YE. Activation of mu opioid receptors in the striatum differentially augments methamphetamine-induced gene expression and enhances stereotypic behavior. J Neurochem. 2012;120:779–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KA, Keefe KA. Regulation of psychostimulant-induced preprodynorphin, c-fos and zif/268 messenger RNA expression in the rat dorsal striatum by mu opioid receptor blockade. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;532:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KA, Noble ES, Gilbert YE. Methamphetamine-induced stereotypy correlates negatively with patch-enhanced prodynorphin and arc mRNA expression in the rat caudate putamen: the role of mu opioid receptor activation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KA, Westwood SC, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Multiple high doses of methamphetamine increase the number of preproneuropeptide Y mRNA-expressing neurons in the striatum of rat via a dopamine D1 receptor-dependent mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:414–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk JC, Adams JL, Barto AG. A model of how the basal ganglia generate and use reward signals that predict reinforcement. In: Houk JC, Davis JL, Beiser DG, editors. Models of Information Processing in the Basal Ganglia. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1995. pp. 249–70. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis WL, Allen LF, Whitelaw RB, Latimer MP, Brace HM, Winn P. An investigation into the role of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in the mediation of locomotion and orofacial stereotypy induced by d-amphetamine and apomorphine in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;58:817–33. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Todaka K, Kuwahara I, Ishizuka Y, Hashiguchi H, Nishimori T, et al. Methamphetamine induces fos expression in the striatum and the substantia nigra pars reticulata in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Brain research. 1998a;809:107–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Todaka K, Kuwahara I, Nakane H, Ishizuka Y, Nishimori T, et al. Methamphetamine-induced Fos expression in the substantia nigra pars reticulata in rats with a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion of the nigrostriatal fibers. Neurosci Res. 1998b;30:355–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabourian M, Venance L, Bourgoin S, Ozon S, Perez S, Godeheu G, et al. Functional mu opioid receptors are expressed in cholinergic interneurons of the rat dorsal striatum: territorial specificity and diurnal variation. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:3301–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Castellanos J, Graybiel AM. Compartmental origins of striatal efferent projections in the cat. Neuroscience. 1989;32:297–321. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D, Niv Y, Ruppin E. Actor-critic models of the basal ganglia: new anatomical and computational perspectives. Neural Networks. 2002;15:535–47. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Minami M, Satoh M, Mizuno N. Immunocytochemical localization of mu-opioid receptor in the rat caudate-putamen. Neurosci Lett. 1995;184:149–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11192-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RM, Strick PL. Macro-architecture of basal ganglia loops with the cerebral cortex: use of rabies virus to reveal multisynaptic circuits. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:449–59. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)43042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapska E, Kaczmarek L. A gene for neuronal plasticity in the mammalian brain: Zif268/Egr-1/NGFI-A/Krox-24/TIS8/ZENK? Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:183–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhorn C, Smith DM, Brown LL. Partial ablation of mu-opioid receptor rich striosomes produces deficits on a motor-skill learning task. Neuroscience. 2009;163:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur A, Shandarin A, LaViolette SR, Parker J, Yeomans JS. Locomotion and stereotypy induced by scopolamine: contributions of muscarinic receptors near the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. Brain Res. 1997;775:144–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Projection neurons of basolateral amygdala: a correlative golgi and retrograde tract tracing study. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28:179–85. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90177-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbrandt J. A nerve growth factor-induced gene encodes a possible transcriptional regulatory factor. Science. 1987;238:797–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3672127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratalla R, Robertson HA, Graybiel AM. Dynamic regulation of NGFI-A (zif268, egr1) gene expression in the striatum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2609–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–28. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladini CA, Tepper JM. GABA(A) and GABA(B) antagonists differentially affect the firing pattern of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons in vivo. Synapse. 1999;32:165–76. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990601)32:3<165::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallanti S, Bernardi S, Raglione LM, Marini P, Ammannati F, Sorbi S, et al. Complex repetitive behavior: punding after bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:376–80. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pert CB, Kuhar M, Snyder SH. Opiate receptor: autoradiographic localization in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3729–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale CW, Jr., Graybiel AM. Fibers from the basolateral amygdala selectively innervate the striosomes in the caudate nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;269:506–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902690404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka E, Graybiel AM. Pathophysiology of Tourette's syndrome: striatal pathways revisited. Brain Dev. 2003;25(Suppl 1):S15–9. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling PD, Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Barrett TB, Kelsoe JR. Differential regulation of immediate-early gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of rats with a high vs low behavioral response to methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2359–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JN, Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Repeated amphetamine administration induces a prolonged augmentation of phosphorylated cyclase response element-binding protein and fos-related antigen immunoreactivity in rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1995;69:441–57. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00274-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A, Moratalla R, Lyford G, Worley PF, Graybiel AM. The activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein Arc is expressed in different striosome-matrix patterns following exposure to amphetamine and cocaine. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2074–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempel A, Zukin RS. Neuroanatomical patterns of the mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors of the rat brain as determined by quantitative in vitro autoradiography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;43:4308–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Trent F, Nakamura S. Postnatal development of the electrical activity of rat nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;54:21–33. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiriet N, Zwiller J, Ali SF. Induction of the immediate early genes egr-1 and c-fos by methamphetamine in mouse brain. Brain Res. 2001;919:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02991-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuno H, Chiken S, Kametani K, Moriizumi T. Efferent projections from the striatal patch compartment: anterograde degeneration after selective ablation of neurons expressing mu-opioid receptor in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal CT, Beverley JA, Willuhn I, Steiner H. Long-lasting dysregulation of gene expression in corticostriatal circuits after repeated cocaine treatment in adult rats: effects on zif 268 and homer 1a. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1615–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Aubier B, Corbille AG, Brami-Cherrier K, Caboche J, Topilko P, et al. Plasticity-associated gene Krox24/Zif268 is required for long-lasting behavioral effects of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4956–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4601-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM. Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Dose-dependent alterations in zif/268 and preprodynorphin mRNA exprsesion induced by amphetamine and methamphetamine in rat forebrain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:909–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Smith AJ, McGinty JF. A single injection of amphetamine or methamphetamine induces dynamic alterations in c-fos, zif/268 and preprodynorphin messenger RNA expression in the rat forebrain. Neuroscience. 1995;68:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00100-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NM, Hiroi N. Preferential localization of self-stimulation sites in striosomes/patches in the rat striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6486–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley RG, Kline IR. Neuronal lesioning with axonally transported toxins. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Guo Y, Vorhees CV, Zhang J. Behavioral responses to cocaine and amphetamine administration in mice lacking the dopamine D1 receptor. Brain Res. 2000;852:198–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Hu XT, Cooper DC, Moratalla R, Graybiel AM, White FJ, et al. Elimination of cocaine-induced hyperactivity and dopamine-mediated neurophysiological effects in dopamine D1 receptor mutant mice. Cell. 1994;79:945–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]