Abstract

Rationale

In gestational exposure studies, a fostered group is frequently used to control for drug-induced maternal effects. However, fostering itself has varying effects depending on the parameters under investigation

Objectives

This study was designed to assess whether maternal behavior contributed to enhanced acquisition (higher number of bar presses compared to controls) of nicotine self-administration (SA) displayed by offspring with gestational nicotine and ethanol (Nic+EtOH) exposure.

Methods

Offspring were exposed to Nic+EtOH throughout full gestation, that is, gestational days (GD) GD2-20 and during postnatal days 2-12 (PN2-12), the rodent third trimester-equivalent of human gestation during which rapid brain growth and synaptogenesis occur. Young adult (PN60) male offspring acquired operant nicotine SA, using a model of unlimited (i.e., 23h) access to nicotine.

Results

Gestational drug treatments did not alter litter parameters (body weight, volume distribution, crown-rump length, and brain weight) or postnatal growth of the offspring. Fostering increased locomotor activity to a novel environment on PN45 regardless of gestational treatment group. Surprisingly, fostering per se significantly increased the SA behavior of drug-naïve pair-fed (PF) controls, so that their drug taking behavior resembled the enhanced nicotine SA observed in non-fostered offspring exposed to Nic+EtOH during gestation. In contrast, fostering did not change the SA behavior of the Nic+EtOH group.

Conclusions

Fostering is shown to be its own experimental variable, ultimately increasing the acquisition of nicotine SA in control, drug-naïve offspring. As such, the current dogma that fostering is required for our gestationally drug-exposed offspring is contraindicated.

Keywords: Gestational Drug Exposure, Fostering, Drug Acquisition, Nicotine, Ethanol

Introduction

Drug exposure during pregnancy has long been reported to negatively affect the development of the fetal brain (Stanwood and Levitt 2004). Maternal behavior in the postnatal environment is also known to play an important role in determining offspring behavior in adolescence and adulthood (Barbazanges et al. 1996). Fostering offspring to drug naïve dams has long been considered necessary to control for lingering drug effects on the dam that may further alter offspring growth and development (Abel and Dintcheff 1978; Golub and Kornetsky 1975). It has become almost dogma in the literature that maternal prenatal drug exposure is a negative contributor to subsequent maternal-offspring interaction. This has resulted in the implementation of fostering as a standard practice without actual empirical testing of the effect that fostering itself may exert.

Our laboratory has previously shown that young adult male rats exposed to nicotine and ethanol(Nic+EtOH) throughout full gestation [i.e., gestational days (GD) GD2-20 and during postnatal days 2-12(PN2-12), the rodent third trimester-equivalent of human gestation during which rapid brain growth and synaptogenesis occur (Dwyer et al. 2009; Puglia and Valenzuela 2010), exhibit increased acquisition of nicotine self-administration (SA) behavior (Matta and Elberger 2007). In addition, there were no significant differences in standard birth parameters between Nic+EtOH offspring and controls (Matta and Elberger 2007). Regardless, a frequent concern of grant and manuscript reviewers is adherence to the literature standard insists on fostering/cross-fostering all offspring to surrogate dams. With careful examination of the historical literature on gestational drug treatment protocols, it appears that the requirement of fostering has been based, at least in part, on studies of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). In such studies, the pregnant/nursing dam received gavaged EtOH at doses that raised her blood ethanol concentration (BEC) to approximately 340mg/dl or greater (Abel and Dintcheff 1978), doses rarely seen in the human population. In these reports, the dams that did manage to survive the EtOH dosing showed significant intoxication, including staggering gait, slowed respiration, and in many cases comatose behavior that lasted for > 2h. Offspring that survived this dosing protocol were born late, had low birth weights, and showed delayed maturation parameters (Eppolito and Smith 2006). Obviously, maternal-offspring interactions were compromised. In contrast, our dosing protocol produced BECs' of approximately 150mg/dl and the dams showed no differences in retrieval or covering behavior (data not shown). The aim of the current study was to determine whether fostering would modify the increased acquisition of nicotine SA behavior, previously seen in offspring with full gestational (GD2-PN12) exposure to Nic+EtOH compared to pair-fed (PF) controls.

Based on the complete lack of differences in litter parameters reported by Matta and Elberger (2007), we felt it was critical to determine if the increased SA behavior of the Nic+EtOH offspring compared to PF controls was the due to the effect of the drugs on the developing pups or the indirect effect of changes in maternal-offspring interaction.

We found that fostering itself has a significant effect on locomotor activity regardless of gestational treatment. Surprisingly, fostering increased nicotine SA only in the fostered PF controls, so that the behavior resembled that seen in the drug treated Nic+EtOH offspring. Therefore, our results show that fostering itself can contribute to altered behavior in the offspring, demonstrating that fostering is not an neutral control. Rather, it should be considered a unique experimental condition that specifically interacts with other treatments.

Materials and Methods

Breeding and Gestational Drug Exposure

The model of gestational exposure was conducted as described in Matta and Elberger (2007). Briefly, Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, IN, USA) were group housed with a reverse light cycle (11 AM off and 11 PM on). Female rats were paired with male breeders overnight and then randomly assigned to the experimental Nic+EtOH group, or the controls (Nicotine-alone or PF groups) on sperm positive day 1 (GD1). Pair feeding was accomplished by providing the control dams with the same amount of food consumed by the Nic+EtOH dam on the same gestational day. For prenatal drug exposure of the experimental Nic+EtOH group, EtOH was administered by daily gastric gavage of 4g/kg from GD2 until GD20 and nicotine 2mg/kg/day (pH = 7.2; calculated as free base; (−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt; Sigma Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was delivered by mini-osmopump (Alzet 2ML4; Durect, Cuppertino, CA, USA) implanted on GD3 (Figure 1A). For prenatal exposure in PF dams, isocaloric maltose dextran (MD) was gavaged, instead of EtOH, and dams received a water-filled mini-osmopump (Figure 1B). Prenatal Nicotine-alone dams were gavaged with MD and fitted with a 2mg/kg/day nicotine mini-osmopump, to serve as the surrogate for Nic+EtOH offspring (Figure 2A). After birth (PN0), litters were randomly culled to 10 pups (5 female + 5 male when possible) on PN1 and drug treatments continued from postnatal PN 2-12, the rodent equivalent of the human third trimester. For both fostered and non-fostered Nic+EtOH offspring, the nicotine mini-osmopump in their dam (Nic+EtOH and Nicotine-alone) was replaced on PN2 with one containing 8mg/kg/day, in order to deliver sufficient nicotine to the pups through the dams' milk, as reported previously (Matta and Elberger 2007); EtOH was delivered by gavaging the offspring twice daily, 30 minutes apart, for a total of 4g/kg (Figure 1A). The non-fostered PF pups received 2 isocaloric MD gavages daily and nursed from their own dam, fitted with a new water mini-osmopump replaced on PN2 to control for surgical effects (Figure 1B). All offspring were weaned at PN21, group housed by litter, and allowed to mature with unrestricted access to food and water until they were single housed starting on PN60 for nicotine SA experiments. Daily handling and pseudo-gavaging of dams prior to pregnancy minimized stress. Pups were never separated from their littermates, except when an individual pup was being gavaged (<1.5 min); each litter was returned to its dam within 5-6 minutes at which time every dam recollected and covered her litter regardless of treatment group. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Figure 1. Protocol for drug treatments in non-fostered offspring.

(A) Dams designated as Nic+EtOH on GD1, received EtOH gavages (4g/kg) beginning on GD2 and a nicotine mini-osmopump (2mg/kg/day) implantation on GD3. The non-fostered pups remained with their dam postnatally. Postnatal exposure to EtOH began on PN2 with twice daily gavages of EtOH (4g/kg total) to each pup. Nicotine exposure was administered by replacing the nicotine pump (8g/kg) in the dam, so that the pups received nicotine through the dams' milk. (B) PF dams received daily gavages beginning GD2 of MD (4g/kg) and a control mini-osmopump of water on GD2. These non-fostered pups also remained with their dam postnatally. Postnatal pup exposure with twice daily gavages of MD (4g/kg total) began on PN2 and a replacement control mini-osmopump was inserted in their dam on PN2.

Figure 2. Protocol for drug treatments in fostered offspring.

(A) Dams designated as Nic+EtOH received EtOH gavages (4g/kg) beginning on GD2 and a nicotine mini-osmopump (2mg/kg/day) implantation on GD3. Offspring were fostered on PN1-2 to a surrogate dam that received prenatal nicotine exposure (Nicotine-alone group) and whose pups were terminated at fostering. Postnatal exposure to EtOH began on PN2 with twice daily gavages of EtOH (4g/kg total) to each offspring. Nicotine exposure was administered by replacing the nicotine pump (8g/kg) in the surrogate dam, so that the pups received nicotine through the dams' milk. (B) PF offspring were fostered to different PF dams on PN1-2. Postnatal exposure for the offspring was given by twice daily gavages of MD (4g/kg total) beginning on PN2 and a replacement control mini-osmopump on PN2 in the surrogate.

Fostering

The fostering of the offspring was completed between PN1-2. Surrogate dams were timed to deliver at the same time as Nic+EtOH or PF litters. Since the experimental paradigm requires a 3-trimester equivalent drug exposure, postnatal Nic+EtOH offspring could not be fostered to a drug-naïve dam because the drug-naïve dam would have adverse reactions to the sudden exposure to an 8mg/kg/day nicotine mini-osmopump on PN2, which is required to deliver the appropriate dose of nicotine to the pups via the dams breast milk (Matta and Elberger 2007). Therefore, the fostered Nic+EtOH pups were placed with the Nicotine-alone surrogate dam that had been exposed to 2mg/kg nicotine prenatally (GD1-21) and gavaged daily with MD; these Nic+EtOH pups were gavaged with EtOH daily (Figure 2A). All the offspring from these designated Nicotine-alone surrogates were sacrificed at the time that the experimental Nic+EtOH offspring were fostered to those dams. Fostered PF offspring were placed with a new PF dam that received a new water mini-osmopump on PN2 and the pups received MD from P2-P12 (Figure 2B).

Litter Parameter

In addition to those previously reported (Matta and Elberger 2007), additional litter parameters were measured on PN1 to determine if there were developmental alterations due to gestational drug treatment. Pups with in utero exposure to Nic+EtOH or PF (n=9 each) from 5 Nic+EtOH litters and 4 PF litters were used to measure body weight (Bwt), volume distribution, crown-rump length, and brain weight. After Bwt measurement, the volume of water displaced when the pup was placed in a cylinder of water was determined, followed by measuring the length from the crown of the head to the beginning of the tail, and then the brain was removed and weighed. Since there were no sex differences in these (or the previous) parameters, the data were pooled.

Locomotor Activity

Activity in a novel environment was measured for adolescent male offspring (PN45) with a Micromax monitoring system (Accuscan Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Rats were placed in individual chambers (45×24×19cm) with dividers preventing each rat from observing the others. Data were collected in 5-minute increments during 1 hour with the lights off.

Nicotine Self-Administration

Young adult male offspring (PN60-75) were allowed chronic, almost unlimited (i.e., 23 h/d) access to bar press for nicotine without prior training, shaping, or food deprivation, using our established model (Valentine et al. 1997). Briefly, after implantation of a jugular cannula, rats were placed into individual operant chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA) enclosed in ventilated, sound-attenuating environmental boxes. The jugular line was connected to a microinjection pump (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) by a single channel swivel (Instech, Plymouth Metting, PA, USA). Rats were given 3 d to recover from surgery; thereafter, rats were provided free access for 23 h daily (1 h daily is required for animal husbandry and downloading data) to two randomly assigned levers positioned 5 cm above the floor, each with a green light above signaling the availability of the drug. Pressing the active lever (“active”) signaled the computer (Graphic State Notation software, Coulbourn Instr.) to activate a pump that delivered 30μg/kg nicotine in a 50-μl heparinized saline bolus over 0.81 s on a fixed ratio (FR1) schedule with a 7 second delay; pressing the inactive lever (“inactive”) had no programmed consequence. Self-administration day 1 (SA d1) was the first day nicotine was made available and the offspring were given 10 days free access to acquire nicotine SA on an FR1 schedule. As per our previously reported criteria for this open access model (Valentine et al. 1997), acquisition of nicotine self-administration behavior to maintenance criteria was defined by: (1) stabilization of the number of active bar presses on the final 3 d to within 15% variation, (2) active bar presses greater than inactive presses, and (3) active presses greater than 12/day.

Statistics

Three-way ANOVA analyses were completed for SA, locomotor activity and the offspring growth curve to examine the interaction between cohort and fostering. One-way ANOVA analysis was completed for litter parameters with a Scheffe post-hoc comparison using SPSS software; significance was set at p<0.05. To reduce the number of animals used, once statistical significance was achieved, further rats were not tested. Values are mean ± SEM and the number of animals/group is indicated within parentheses in the text and figures.

Results

Litter Parameters

Litter parameters were measured on PN1 using 2 pups per treatment group for Nic+EtOH (n=9) and PF cohorts (n=9) (Table 1). These parameters were chosen because they are indicators of exposure to doses of gestational EtOH, used in models of FAS; such doses are greater than that administered in the current study. In marked contrast to reports on FAS, there were no differences in volume distribution, crown-rump length, or brain weight for Nic+EtOH or their PF controls. Similar to previous observations (Matta and Elberger 2007), there was no significant difference in the birth weight between the Nic+EtOH and PF offspring. In addition, peak BECs in Nic+EtOH dams and their offspring (154±6 and 151±6 mg/dl, respectively) were comparable to those commonly reported in humans cited for a DWI (i.e., driving while intoxicated) violation (Matta and Elberger 2007). Also, peak plasma nicotine levels (30±3 and 21±2 ng/ml, respectively) were lower than those eliciting nicotine-induced hypoxia (Slotkin et al. 1987). These data demonstrate that offspring were exposed to moderate doses of EtOH similar to those frequently imbibed by human binge drinkers and moderate smokers. Taken together, these data indicate that gestational drug treatment did not alter general indices of offspring health.

Table I. PN1 Litter Parameters.

No significant differences were seen for birth weight (PN1), volume distribution, crown-rump length, and brain weight. This demonstrates that the gestational drug exposure did not have any overt developmental effect on the offspring (Results are reported as average ± SEM)

| Cohort | Birth Weight PN1 (g) | Volume Displacement (ml) | Crown-Rump Length (cm) | Brain Weight (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nic+EtOH (n=9) | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 255.3 ± 6.9 |

| PF (n=9) | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 246.3 ± 8.4 |

Offspring Growth Curve

Figure 3 illustrates postnatal body weight gain among treatment groups. Fostering had no effect on body weight gain in the Nic+EtOH offspring, nor did it alter weight gain in the PF offspring; weight gain was similar in both treatment groups (p=0.27). These data demonstrate that neither fostering nor drug treatments altered growth during postnatal drug administration.

Figure 3. Postnatal Bwt gain in fostered and non-fostered Nic+EtOH and PF offspring.

Bwt gain was not influenced by full gestational exposure nor by postnatal fostering.

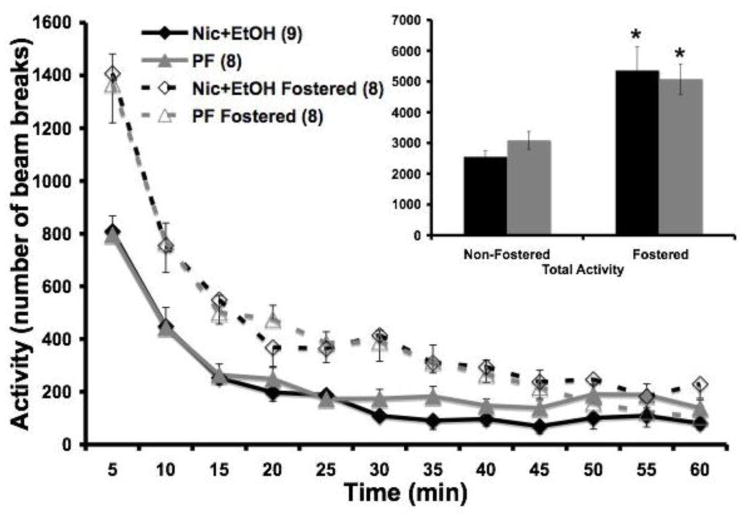

Locomotor Activity

Fostered Nic+EtOH and PF offspring had a higher total activity over the 1 hour session on PN45 compared to non-fostered Nic+EtOH and PF offspring (F1,348=4.1; p<0.05) (Figure 4). Similarly, the non-fostered offspring (Nic+EtOH and PF) did not differ significantly from each other nor did the fostered Nic+EtOH and PF offspring behaviors differ.

Figure 4. Locomotor Activity for fostered and non-fostered Nic+EtOH and PF offspring at PN45.

Fostered offspring demonstrated a higher number of beam breaks compared to the non-fostered offspring, regardless of full gestational drug treatment. This demonstrates that fostering itself can increase activity in a novel environment (Fostered vs. Non-fostered offspring *p=<.05)

Nicotine Self-Administration (SA)

To demonstrate that offspring learned the SA behavior active vs. inactive lever presses were compared. Both non-fostered and fostered PF rats expressed significant higher active lever presses compared to inactive lever presses for the entire 10-day period of nicotine SA behavior; PF non-fostered offspring (F1,100=97.36 p<0.01); PF fostered (F1,100=150.68, p<0.01). Surprisingly, the fostered PF offspring had significantly increased nicotine SA compared to non-fostered PF offspring (F1,100=16.55, p<0.01) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, fostered offspring acquired the behavior by d4 (p<0.05, active vs. inactive bar presses by day), while non-fostered required a longer time interval (d8; p<0.05, active vs. inactive presses by day). Fostered PF offspring also exhibited significantly more bar presses than the non-fostered group during the last 3 d: 77±8 vs. 50±8 fostered vs. non-fostered, respectively (F1,34=5.7, p=0.02).

Figure 5A. In the PF control young-adult offspring, fostering alone significantly increased nicotine SA.

PF offspring, both fostered and non-fostered, were given 23-hour access to acquire self-administration of 30ug/kg/inj of nicotine without priming, shaping, or training. Fostering increased lever presses on the active bar delivering nicotine 30μg/kg/inj (solid line), without affecting behavior on the inactive bar (no consequences lever; dashed line); *p<0.05, Active bar presses, PF non-fostered vs. PF fostered. (B) Fostering had no effect on the nicotine SA by the Nic+EtOH young adult offspring. Full gestational exposure (GD2-PN12) to Nic+EtOH resulted in increased levels of nicotine SA, as well as a shortening in the onset of initiation of nicotine SA, regardless of fostering status. Surprisingly, PF controls that had been fostered, but had no gestational drug exposure, demonstrated comparable levels of nicotine SA to Nic+EtOH offspring.

In contrast, Figure 5B shows that fostering Nic+EtOH offspring did not alter their SA behavior (p=0.99 for Nic+EtOH vs. Nic+EtOH Fostered). Active bar presses were greater than inactive presses in both groups: non-fostered Nic+EtOH offspring (F1,120=136.91 p<0.01); Nic+EtOH Fostered (F1,120=70.67 p<0.01; data not shown). Non-fostered Nic+EtOH, fostered Nic+EtOH, and fostered PF offspring showed significantly higher levels of nicotine SA in comparison to non-fostered PF offspring (active bar presses: F1,220=6.62, p<0.01).

Discussion

Our data show that early postnatal fostering per se markedly increased nicotine SA in young adult PF offspring – the control group for Nic+EtOH full gestational treatment. These results indicate that the alteration of postnatal environment (i.e. maternal behavior; maternal grooming, nursing, etc.) increases the long-term drug taking behavior of the offspring.

There is a limitation of the three-trimester model of full gestational drug exposure, which was designed to approximate full three-trimester exposure in humans. During the third trimester (i.e. postnatally) in this model, we have attempted to approximate the continuous exposure of the postnatal pups to the blood nicotine levels they had while in utero. In contrast, since the EtOH was administered to the pregnant dams as a binge dose, we also administered the EtOH to the postnatal pups as a binge dose in order to control for BEC. That is, even if we had gavaged the nursing dam, there was no way we could guarantee that each individual pup would drink sufficient breast milk with EtOH within the timeframe of EtOH metabolism in the dam.

Full gestational exposure to relatively moderate amounts of both nicotine and EtOH did not alter birth parameters (PN1) or body weight gain in offspring (PN1-PN21) compared to PF controls. These results are in agreement with our previous report in which sex ratio, stillbirths, righting reflex, and the day of eye opening were similar between all treatment groups (Matta and Elberger 2007). Previous studies have shown that gestational EtOH exposure (4g/kg and 6g/kg) was associated with low birth weight and behavioral abnormalities in the offspring (Abel 1978; Abel and Dintcheff 1978). However, the outcome of low birth weight was inconsistent, even following relatively high doses of 6g/kg (Caul et al. 1979; Matta and Elberger 2007; Osborne et al. 1980); this could reflect differences in the mode of EtOH delivery or rat strain. Prenatal nicotine exposure has also been associated with low birth weight of pups, however this is seen only at higher doses (>6mg/kg/day) and not at the lower dose used herein (i.e., 2mg/kg/day) (Eppolito and Smith 2006; Navarro et al. 1989; Slotkin et al. 1987). Depending on drug and dose, prenatal drug exposure also may modify aspects of the postnatal environment. It has been shown that offspring with prenatal EtOH exposure fail to gain weight at the same rate as control offspring after being born with low birth weight and this lack of weight gain was thought to be attributed to factors in the postnatal environment (i.e. the drug exposed dam) and not to the prenatal EtOH exposure itself (Abel and Dintcheff 1978). In contrast, cross-fostering of control offspring to EtOH exposed dams did not alter the weight gain of these offspring, demonstrating that the EtOH-treated dams themselves did not adversely affect the growth of the offspring (Osborne et al. 1980). Despite the lack of any correlation between drug-exposure in dams and offspring behavior, the authors of that early report still strongly recommended fostering to drug naïve-dams. However, our results show that regardless of gestational treatment (Nic+EtOH or PF), the postnatal growth curves for non-fostered offspring were consistent with our previous report (Matta and Elberger 2007) and did not differ from each other. Taken together, these data indicate that neither fostering nor gestational drug treatment altered the overall bodily growth and gross CNS maturation of offspring.

Fostering at different postnatal time points can exert divergent effects on behavior (Barbazanges et al. 1996; Darnaudery et al. 2004). It has been reported that maternal separation stress in early human life dysregulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress axis, thus increasing the risk for drug taking behavior (Andersen and Teicher 2009; Vallee et al. 1999). Also, rat offspring fostered at PN5 or PN12 displayed enhanced stress responses, similar to those detected in offspring exposed to maternal separation at the same time intervals (Barbazanges et al. 1996). However, offspring fostered at PN1 did not display these increased stress responses (Darnaudery et al. 2004). In rodents, prolonged maternal separation stress (3h) at different postnatal ages increased subsequent dopamine responses to stress or stimulants in the mesocorticolimbic reward pathway (Brake et al. 2004). This reward pathway, which includes the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, and medial prefrontal cortex, is essential to the acquisition of drug self-administration (Koob and Nestler 1997). In addition to reported alterations in the HPA axis, altered maternal-offspring interactions also can affect components of this reward pathway. For example, repeated or acute separation stress (1-3h/daily from PN3-21), altered multiple neuronal circuits. Specifically, 1-hour separation from PN1-20 increased serotonin levels and serotonin turnover (5-HIAA/5HT ratio) in medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Jezierski et al. 2006), while 1-hour separation from PN1-21 increased GABA in the medial prefrontal cortex (Helmeke et al. 2008). Finally, a recent report (Champagne and Curley 2009) showed that cross-fostering of drug naïve WKY pups to an SHR surrogate rat caused a shift in phenotype to that of SHR. Studies in progress are centered on modulation of GABAergic inhibition and glutamatergic excitation in the VTA of the Nic+EtOH offspring, as well as specific epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation in these neuronal types.

The fostering/cross-fostering of offspring and the resultant locomotor activity has been reported to produce varied results. While offspring fostered on PN1 did not differ from controls, groups with maternal separation from the dam had higher locomotor response (Barbazanges et al. 1996). Adult rats fostered at later neonatal time points (PN5 or PN12) had a significantly higher locomotor responses compared to non-fostered offspring (Barbazanges et al. 1996). Also, it has been reported that neither fostering nor cross-fostering of Wistar and Fisher rats altered total motor activity for open field behavior. In contrast, a report on the cross-fostering of Lewis and Fisher strains demonstrated significant differences in locomotor activity for both males and females, whereas in-strain fostering of the offspring produced no differences in activity (Gomez-Serrano et al. 2001). Locomotor activity to a novel environment has been used in the past to separate animals into higher anxiety vs. lower anxiety responder groups (Gancarz et al. 2011). High responder groups of younger rats (4 months old) have been associated with increased HPA axis activity in response to stress (Dellu et al. 1996). Responding for nicotine, methamphetamine, and even visual stimulus, has also been correlated with high locomotor response to novelty (Gancarz et al. 2011; Suto et al. 2001). Our locomotor results show that only fostered offspring, regardless of full gestational treatment group, had an increased response to a novel environment in adolescence. In addition, the inactive lever presses during self-administration did not increase with prenatal drug exposure or fostering, therefore demonstrating that offspring were not hyperactive in the SA chambers. We conclude from this that increased locomotor activity in a novel environment is not necessarily a predictor of a high nicotine self-administration.

In our study, we did not expect to see behavioral changes, since the PF control offspring were fostered on PN1 and there were no differences in litter parameters. Yet, we found dramatic increases in the nicotine SA behavior of fostered PF offspring that was comparable to the behavior of experimental offspring with full gestational exposure to Nic+EtOH. Self-administration behavior of the non-fostered PF offspring remained consistent with data previously reported (Matta and Elberger 2007). Active bar presses were less in non-fostered than fostered PF (e.g. 50±8 vs. 77±8) and acquisition time was longer (i.e. 8 days compared to 4 days for Nic+EtOH). Therefore, fostering alone, even in the absence of gestational exposure to drugs, is sufficient to alter nicotine SA behavior.

In contrast, fostering itself did not change the enhanced nicotine SA behavior of Nic+EtOH pups. There were no differences in the number of active bar presses, in the ratio of active to inactive presses or in the number of days to acquire stable nicotine SA. The lack of any effect of fostering in these pups could be due, at least in part, to a maximal or “ceiling” effect of gestational drug treatment on the developing brain of Nic+EtOH offspring.

Variability in the effect of fostering has been reported for various drugs. Rats with prenatal methamphetamine exposure (5mg/kg/day) show improvement in maturation tests when fostered to drug-naïve dams (Pometlova et al. 2009). Similarly, while non-fostered rat offspring with in utero saline or morphine exposure (5mg/kg injection GD11-13, 10mg/kg GD14-18) did not exhibit higher operant response rates for cocaine (0.5mg/kg/inj) compared to controls, fostering itself increased responding for cocaine regardless of prenatal treatment group (Vathy et al. 2007). In our previous study, cross-fostering of offspring with prenatal nicotine exposure (3mg/kg/day) did not affect the increase in the dopaminergic response to a nicotine injection. However, cross-fostering of controls resulted in an increase in accumbal dopamine similar to that seen in offspring with prenatal nicotine exposure (Kane et al. 2004). These studies, as well as our data herein, support the idea that the fostering procedure itself, assumed to reduce negative maternal effects by many, is contraindicated and may actually introduce new sources of variance, subsequently changing pup behavior (Darnaudery et al. 2004).

In summary, fostering of PF offspring significantly increased the nicotine SA behavior in young adult rats without altering the enhanced SA behavior of the Nic+EtOH offspring. Indeed, the experimental practice of fostering alone elevated the nicotine self-administration behavior of PF offspring to levels comparable to these Nic+EtOH rats. Therefore, in the current model of unlimited (i.e. 23-hour) nicotine access, fostering introduces a major confound that precludes its use as a control for environmental interactions during the neonatal period for our full gestational model of Nic+EtOH exposure. Thus, the dogmatic assertion that fostering is a crucial control is inaccurate, rather fostering is its own experimental variable.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary data were presented at the 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego CA. The authors appreciate the generous assistance of Dr. Andrea Elberger for her expertise and intellectual input in reading the final draft and to Kathy McAllen for her technical expertise. This work was supported by DA15525 (SGM) and a grant from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Neuroscience Institute (EER).

References

- Abel EL. Effects of ethanol on pregnant rats and their offspring. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1978;57:5–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00426950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel EL, Dintcheff BA. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and development in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;207:916–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Desperately driven and no brakes: developmental stress exposure and subsequent risk for substance abuse. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:516–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbazanges A, Vallee M, Mayo W, Day J, Simon H, Le Moal M, Maccari S. Early and later adoptions have different long-term effects on male rat offspring. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7783–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07783.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake WG, Zhang TY, Diorio J, Meaney MJ, Gratton A. Influence of early postnatal rearing conditions on mesocorticolimbic dopamine and behavioural responses to psychostimulants and stressors in adult rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1863–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caul WF, Osborne GL, Fernandez K, Henderson GI. Open-field and avoidance performance of rats as a function of prenatal ethanol treatment. Addict Behav. 1979;4:311–22. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Curley JP. Epigenetic mechanisms mediating the long-term effects of maternal care on development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnaudery M, Koehl M, Barbazanges A, Cabib S, Le Moal M, Maccari S. Early and later adoptions differently modify mother-pup interactions. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:590–6. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellu F, Mayo W, Vallee M, Maccari S, Piazza PV, Le Moal M, Simon H. Behavioral reactivity to novelty during youth as a predictive factor of stress-induced corticosterone secretion in the elderly--a life-span study in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:441–53. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(96)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:125–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppolito AK, Smith RF. Long-term behavioral and developmental consequences of pre- and perinatal nicotine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:835–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM, San George MA, Ashrafioun L, Richards JB. Locomotor activity in a novel environment predicts both responding for a visual stimulus and self-administration of a low dose of methamphetamine in rats. Behav Processes. 2011;86:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub M, Kornetsky C. Effects of testing age and fostering experience on seizure susceptibility of rats treated prenatally with chlorpromazine. Dev Psychobiol. 1975;8:519–24. doi: 10.1002/dev.420080608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Serrano M, Tonelli L, Listwak S, Sternberg E, Riley AL. Effects of cross fostering on open-field behavior, acoustic startle, lipopolysaccharide-induced corticosterone release, and body weight in Lewis and Fischer rats. Behav Genet. 2001;31:427–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1012742405141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmeke C, Ovtscharoff W, Jr, Poeggel G, Braun K. Imbalance of immunohistochemically characterized interneuron populations in the adolescent and adult rodent medial prefrontal cortex after repeated exposure to neonatal separation stress. Neuroscience. 2008;152:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski G, Braun K, Gruss M. Epigenetic modulation of the developing serotonergic neurotransmission in the semi-precocial rodent Octodon degus. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane VB, Fu Y, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Gestational nicotine exposure attenuates nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell of adolescent Lewis rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:521–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Nestler EJ. The neurobiology of drug addiction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:482–97. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta SG, Elberger AJ. Combined exposure to nicotine and ethanol throughout full gestation results in enhanced acquisition of nicotine self-administration in young adult rat offspring. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:199–213. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro HA, Seidler FJ, Schwartz RD, Baker FE, Dobbins SS, Slotkin TA. Prenatal exposure to nicotine impairs nervous system development at a dose which does not affect viability or growth. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23:187–92. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne GL, Caul WF, Fernandez K. Behavioral effects of prenatal ethanol exposure and differential early experience in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1980;12:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pometlova M, Hruba L, Slamberova R, Rokyta R. Cross-fostering effect on postnatal development of rat pups exposed to methamphetamine during gestation and preweaning periods. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2009;27:149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglia MP, Valenzuela CF. Repeated third trimester-equivalent ethanol exposure inhibits long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region of neonatal rats. Alcohol. 2010;44:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Orband-Miller L, Queen KL, Whitmore WL, Seidler FJ. Effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on biochemical development of rat brain regions: maternal drug infusions via osmotic minipumps. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;240:602–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanwood GD, Levitt P. Drug exposure early in life: functional repercussions of changing neuropharmacology during sensitive periods of brain development. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto N, Austin JD, Vezina P. Locomotor response to novelty predicts a rat's propensity to self-administer nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:175–80. doi: 10.1007/s002130100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JD, Hokanson JS, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Self-administration in rats allowed unlimited access to nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:300–4. doi: 10.1007/s002130050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee M, MacCari S, Dellu F, Simon H, Le Moal M, Mayo W. Long-term effects of prenatal stress and postnatal handling on age-related glucocorticoid secretion and cognitive performance: a longitudinal study in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2906–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vathy I, Slamberova R, Liu X. Foster mother care but not prenatal morphine exposure enhances cocaine self-administration in young adult male and female rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:463–73. doi: 10.1002/dev.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]