Abstract

Inosine, a naturally occurring purine formed from the breakdown of adenosine, is associated with immunoregulatory effects. Evidence shows that inosine modulates lung inflammation and regulates cytokine generation. However, its role in controlling allergen-induced lung inflammation has yet to be identified. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of inosine and adenosine receptors in a murine model of lung allergy induced by ovalbumin (OVA). Intraperitoneal administration of inosine (0.001–10 mg/kg, 30 min before OVA challenge) significantly reduced the number of leukocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils recovered in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of sensitized mice compared with controls. Interestingly, our results showed that pre-treatment with the selective A2A receptor antagonist (ZM241385), but not with the selective A2B receptor antagonist (alloxazine), reduced the inhibitory effects of inosine against macrophage count, suggesting that A2A receptors mediate monocyte recruitment into the lungs. In addition, the pre-treatment of mice with selective A3 antagonist (MRS3777) also prevented inosine effects against macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils. Histological analysis confirmed the effects of inosine and A2A adenosine receptors on cell recruitment and demonstrated that the treatment with ZM241385 and alloxazine reverted inosine effects against mast cell migration into the lungs. Accordingly, the treatment with inosine reduced lung elastance, an effect related to A2 receptors. Moreover, inosine reduced the levels of Th2-cytokines, interleukin-4 and interleukin-5, an effect that was not reversed by A2A or A2B selective antagonists. Our data show that inosine acting on A2A or A3 adenosine receptors can regulate OVA-induced allergic lung inflammation and also implicate inosine as an endogenous modulator of inflammatory processes observed in the lungs of asthmatic patients.

Keywords: Inosine, Adenosine receptors, Allergy, Ovalbumin

Introduction

Extracellular signalling nucleosides, such as adenosine and inosine, have important and diverse roles in biological processes, including neurotransmission in the peripheral and central nervous system, exocrine and endocrine secretion, platelet aggregation, smooth muscle contraction, pain sensation and modulation of cardiac function. Evidence has shown that these purines also modulate immune responses and inflammation [1, 2] by acting on G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors [3]. Classified as A1, A2A, A2B and A3 [3], these receptors differ in their affinities and intracellular signalling pathways and are widespread in organs and cells [3–5], as well as in immune cells and the respiratory tract [6, 7]. The nucleoside adenosine, a well-characterized purine, is generated from adenosine triphosphate by cells under certain physiological conditions and can be produced in elevated concentrations in response to tissue injury during hypoxia and inflammation [7, 8]. The potential role of adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in the pathogenesis of asthma has been supported by the bronchoconstrictor effects observed after their topical administration in the airways of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease but not in those of healthy subjects [9–12]. In contrast, experimental data demonstrated that adenosine and its analogues have also been shown to exert protective and anti-inflammatory effects in the airways, reducing the leukocyte cell count in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and decreases airway remodelling in murine models of asthma, an effect related to adenosine A2 receptors activation [13, 14].

Inflammation, hypoxia and tissue injury cause adenosine degradation and the generation of its metabolite inosine [15], a process mediated by adenosine deaminase [7, 16]. Inosine has been reported, for a long time, to be an inert metabolite devoid of relevant biological effects [17]. Recent studies indicate, however, that similar to adenosine, inosine exerts immunomodulatory actions throughout the heterogeneous family of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors. Studies had shown that like adenosine, inosine also presents anti-inflammatory effects related with the activation of adenosine receptors, mainly the A2A and A3, that include reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and protective tissue effects from endotoxin-induced [4, 18] and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS)-induced inflammation [19]. In contrast, other experimental studies have demonstrated that inosine appears to have a dual effect, stimulating mast cell degranulation via A3 receptors and possibly accounting for allergic inflammatory responses [5, 20].

In the airways, it has been demonstrated that inosine exerts anti-inflammatory and protective effects, reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2, decreasing leukocyte recruitment into lung tissue and alveolar spaces [21]. In addition, inosine appears to prevent changes in airway morphology after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure [21]. Moreover, INO-2002, an inosine analogue, demonstrated similar effects after intratracheal LPS administration [22]. Despite all that is known about the effects of inosine, the mechanisms underlying its role in controlling the lung repercussions of allergic inflammation are still unknown. Recent data obtained from our group showed that inosine reduced carrageenan-induced acute pleural inflammation, an effect that involves A2A and A2B adenosine receptors [23]. Accordingly, literature data indicates that the activation of A2 adenosine receptors subtypes is related with down-regulation of inflammation and immune responses [4, 24, 25]. Conversely, the adenosine A3 receptor activation have a enigmatic role in inflammation, increasing allergic inflammation activating mast cells or reducing inflammatory process inhibiting eosinophils chemotaxis and degranulation [5, 20]. Considering these evidences, in the current study, we aimed to investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of inosine in a murine experimental asthma model, as well as the role of the A2 and A3 adenosine receptor in mediating inosine effects.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The experiments were conducted according to the ethical statements established by the national guidelines for the use of experimental animals Colégio Brasileiro de Experimentação Animal (COBEA) and performed after approval by the ethics committee at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of the University of São Paulo (approval protocol number 58/2009) and Federal University of Paraná (approval protocol number 320/2008). Before the procedures to collect the animal samples, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Animals

Experiments were conducted with female BALB/c mice (25–35 g) from the pharmacology departmental animal facilities at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of the University of São Paulo. The animals were housed at 22 ± 2 °C under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 6 a.m.), and food and water were provided ad libitum.

Materials

The following substances were used: inosine, caffeine, methacholine, chicken egg ovalbumin (OVA) grade V (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), 4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol (ZM241385), alloxazine (Tocris Bioscience, Park Ellisville, MO, USA), 2-Phenoxy-6-(cyclohexylamino) purinehemioxalate (MRS3777; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Cultilab, Campinas, Brazil), aluminium hydroxide (Sanofi-Synthélabo, São Paulo, Brazil), ketamine, and xylazine (Vetbrands Saúde Animal, Brazil).

Drug treatments

Mice were treated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with inosine (0.001–10 mg/kg) 30 min before the OVA challenge. Selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.), selective adenosine A2B receptor antagonist alloxazine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and selective adenosine A3 receptor antagonist MRS3777 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) were administered 30 min before inosine treatment. The same selective antagonists were given in absence of inosine to evaluate the per se effects. The doses of antagonists used here were based on previous in vivo studies [23, 26].

The treatments were carried out twice a day, on days 14 and 15, before each antigen challenge [OVA, 1 %, aerosol, 15 min, in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]. Inosine and the adenosine-receptor antagonists were diluted in Tween 20 plus sterile PBS. The final concentration of Tween 20 did not exceed 10 % and caused no effects per se.

Experimental procedures

OVA-induced allergic inflammation

Female BALB/c mice 6–8 weeks were immunized subcutaneously on days 0 and 7 with 10 μg of chicken egg OVA grade V absorbed in 0.4 ml of a saturated aluminium hydroxide solution (2.5 mg/kg). On days 14 and 15, mice were placed in a 12-L Plexiglas container and exposed twice a day (15 min) to an aerosol solution of OVA (1 %/PBS). To study the inosine effects on bronchial responsiveness to methacholine, the protocol adopted was the same, but on day 15, mice were exposed twice a day (15 min) to OVA 3 %/PBS, to ensure the airway hyperactivity. Negative control mice received no treatment. All measurements were performed 24 h after the last aerosol challenge.

BALF leukocytes count

Mice were euthanized via aorta exsanguination after anaesthetisation with ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (20 mg/kg, i.p.). A plastic cannula connected to a plastic syringe containing sterile saline salt solution was inserted into the trachea to obtain BALF. To quantify the total cells recovered, an aliquot of BALF (90 μL) was added to 10 μL of violet crystal solution (0.2 % violet crystal plus 30 % acetic acid). Total cells in BALF were determined using optical microscopy with an improved Neubauer haemocytometer (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK). Differential cell counts in BALF were determined with cytospin preparations of BALF aliquots (100 μL) centrifuged at 300×g for 1 min using a Shandon Cytospin 2 (Shandon Southern Instruments, Sewickley, PA, USA) at room temperature. Differential blood leukocytes were identified in blood smears. Differential cells were quantified using optical microscopy in samples stained with Diff-Quick (DADE Behring, Marburg, Switzerland). A total of 200 cells were quantified, and the numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils and mononuclear cells were determined using standard morphological criteria [27].

Ex vivo lung release of cytokines

Lung fragments from allergic mice and controls were collected and prepared for organ culture as described by Proust et al. [28]. In brief, 24 h after the last antigen challenge, the lungs of euthanized mice, either treated or not treated with inosine or adenosine-receptor antagonists, were perfused through the right ventricle with 5 ml of PBS to remove intravascular blood. Thereafter, four fragments with the same weight were separated and cultured in 24-well plastic plates (Falcon-Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ, USA) containing 1 ml of DMEM at 37 °C in 5 % CO2/air for 24 h. The DMEM was prepared with 0.5 % penicillin-streptomycin (10 mg/kg). Conditioned media from all cultures were collected and stored at −80 °C for cytokine determinations.

Cytokine measurements

Cytokine assays were conducted in cell culture supernatants obtained from lung explants. IL-4 and IL-5 levels were measured using a conventional commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), following the instructions of the manufacturer.

Lung histology

Lungs of mice were removed and fixed in 10 % formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. The block was cut into sections 3-μm thick, and the tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for morphologic analysis and with toluidine blue for quantification of lung mast cells. The analysis of airway area or mast cell quantification was performed using ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA). The epithelial cell proliferation was determined as the ratio between the airway area occupied by epithelial cells to basement membrane and the airway diameter. The results were expressed square micrometre per micrometre. Mast cell quantification was expressed in cells per square millimetre. At least five to six bronchioles were evaluated per slide.

Bronchial responsiveness to methacholine “in vivo”

The bronchial responsiveness to methacholine (MCh) was measured 24 h after the challenge with aerosolized OVA and treated with inosine, ZM241385 or ZM241385 plus inosine. The trachea was cannulated with a 20-gauge tube under anaesthesia with 100 mg/kg of ketamine and 20 mg/kg of xylazine, i.p., and the animals were ventilated at 450 cycles/min, with a computer-controlled, small animal ventilator (flexiVent 5.2; SCIREQ, Montreal, QC, Canada), with a tidal volume of 10 ml/kg, against an artificial positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O. Before the measurement of airway resistance (R) and elastance (E), the lungs were inflated two times to total lung capacity (TLC) to standardize the volume among animals and to establish the baseline. Freshly prepared methacholine in PBS, in dose of 100 mg/ml, were subsequently delivered to the airway by transiently diverting the inspiratory limb of the ventilator through the reservoir of an ultrasonic nebulizer for 30 s. The resistance and elastance were measured at 30-s intervals for 5 min after methacholine delivery, and the maximum value following each measurement was used to establish the difference between the groups. To assess the relaxation effects of inosine, ZM241385 or the involvement of A2A receptors, where the inosine and ZM241385 were co-administered, the constrictive response to methacholine was determined as described above. The pressure–volume and flow data were fit to a single-compartment model to derive the measurements of airway resistance and elastance.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± SEM, excluding the ID50 values, which are reported as geometric means accompanied by their respective 95 % confidence limits. The ID50 value was determined by nonlinear regression from individual experiments using GraphPad software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical significance of the differences between groups was determined using analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test. P values less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) were considered significant.

Results

Effect of inosine treatment on OVA-induced allergic lung inflammation

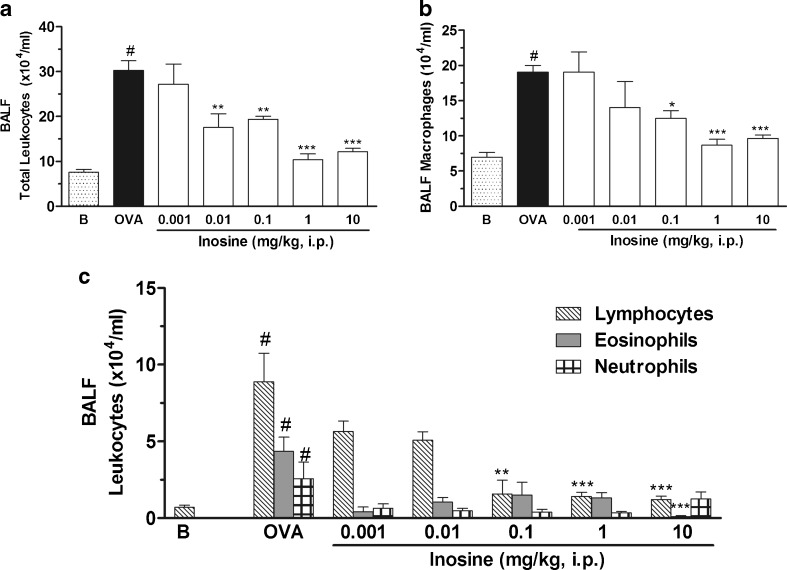

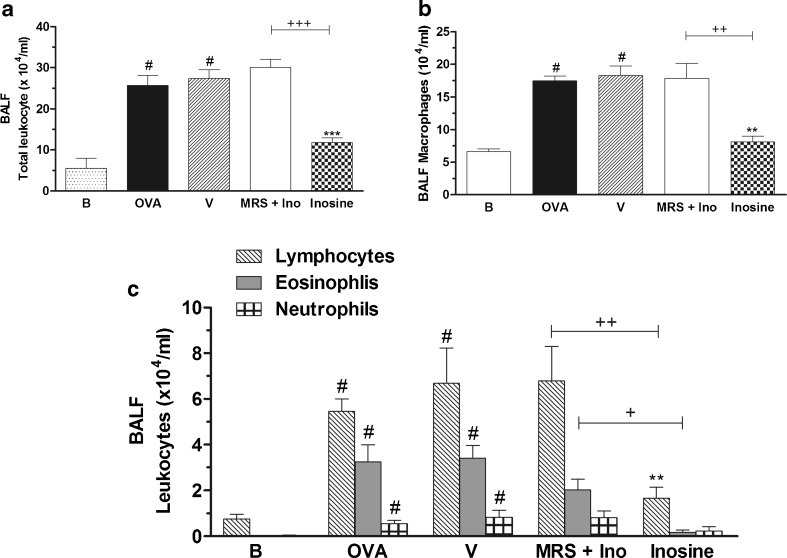

Figure 1a shows that the total number of leukocytes recovered in the BALF of mice challenged with OVA was significantly higher than that of the basal group. This increase was primarily attributable to macrophages (Fig. 1b), lymphocytes and eosinophils (Fig. 1c). Inosine significantly decreased the number of cells collected in BALF after the OVA challenge [ID50 = 0.094 mg/kg (confidence interval, 0.023–0.37)], reaching a maximal inhibitory response at dose of 1 mg/kg. The differential cell count revealed that inosine at this same dose reduced the macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils cell counting. The dose of 10 mg/kg exhibited a similar effect against the total cell count and the number of macrophages. Interestingly at dose of 10 mg/kg, inosine almost abolished the lymphocyte and eosinophil count in the BALF, being more effective than the dose of 1 mg/kg. Taking into account these results, the dose of 10 mg/kg was chosen to study the involvement of adenosine receptors in inosine effects. Neutrophils accounted for less than 6 % of BALF cells collected after the OVA challenge and were unaffected by inosine.

Fig. 1.

Effects of inosine on OVA-induced inflammation. Immunized mice were treated with inosine 30 min before the challenge with OVA, and 24 h after, the total leukocyte counting (a) and the differential counting of macrophages (b), lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils (c) were performed in the BALF. B basal group not immunized, challenged or treated; OVA OVA-immunized and challenged mice; doses of 0.001–10 mg/kg correspond to the OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated with inosine before each challenge. Each column represents the mean of the values obtained in five to eight animals, and the error bars indicate the SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with the allergic control group (OVA); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B)

Adenosine receptors and inosine effects

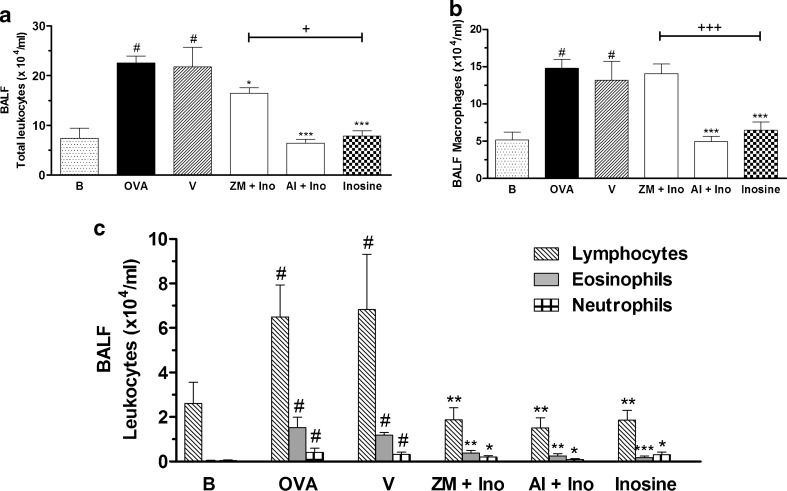

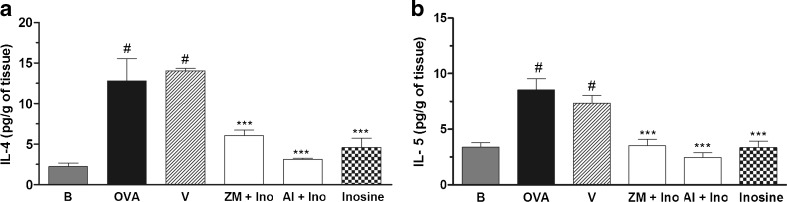

Figure 2 shows that ZM241385, a selective A2A receptor antagonist, given 30 min before inosine treatment, reversed the inosine effects. Furthermore, pre-treatment with alloxazine (5 mg/kg, i.p.), a selective adenosine A2B receptor antagonist, did not change the effects of inosine on total or differential cell counts (Fig. 2a–c), whereas treatment with ZM241385 reversed the inhibitory effect of inosine on macrophage counts in the BALF of allergic mice (Fig. 2b). The administration of ZM241385 or alloxazine alone did not affect the total or differential leukocyte counts in the BALF (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Effects of A2 adenosine receptors antagonists on inosine effects in the OVA-induced inflammation. Immunized mice were pre-treated with ZM241385 (ZM) or alloxazine (Al), 30 min before inosine. The treatments were performed 30 min before the challenges. After 24 h, the total leukocyte counting (a) and the differential counting of macrophages (b), lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils (c) were performed in the BALF. B basal group not immunized, challenged or treated; OVA ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice; V ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with vehicle used to dilute the antagonists; ZM + Ino ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with ZM241385 and treated with inosine; Al + Ino ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with allozaxine and treated with inosine; Inosine ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with inosine. Each column represents the mean of the values obtained in five to eight animals, and the error bars indicate the SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with vehicle group (V); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B); +P < 0.05; +++P < 0.001 when compared with the inosine-treated group

Table 1.

Effects of selective adenosine receptor antagonists in OVA-induced allergic lung inflammation

| Leukocyte count (×104/ml) | Totals | Macrophages | Lymphocytes | Eosinophils | Neutrophils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control groups | |||||

| Basal | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| OVA (1 %) | 24.7 ± 0.8* | 17.5 ± 0.7* | 5.4 ± 0.5* | 1.8 ± 0.4* | 0.5 ± 0.1* |

| Vehicle (Tween 20) | 24.4 ± 1.2* | 16.4 ± 1.0* | 5.6 ± 0.7* | 1.9 ± 0.0* | 0.9 ± 0.3* |

| Group treated with antagonists | |||||

| ZM241385 (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.) | 23.0 ± 1.7 | 14.2 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 1.9 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| Alloxazine (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.) | 21.3 ± 0.9 | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| MRS3777 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.) | 22.1 ± 1.7 | 18.8 ± 1.7 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

The difference between groups was determined by ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test

*P < 0.001 when compared to basal group

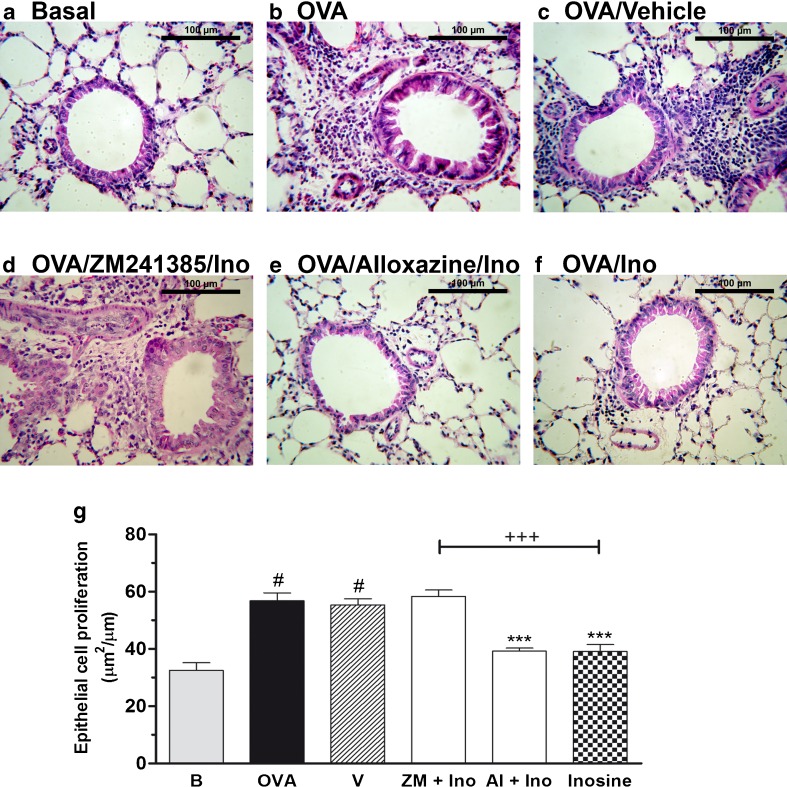

Examination of lung tissue stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 3a–g) revealed an increased number of leukocytes in the peribronchial and perivascular areas of the lungs of allergic mice (Fig. 3b). Inosine clearly prevented the leukocyte accumulation in lungs (Fig. 3f, g), which was not observed after inosine vehicle treatment (Fig. 3c). The basal control group showed no significant increase in leukocyte accumulation. Moreover, ZM241385 (Fig. 3d) prevented the anti-inflammatory effects of inosine, whereas alloxazine did not interfere with its effects (Fig. 3e). Finally, epithelium hypertrophy was also observed (Fig. 3g) in OVA-challenged mice and was prevented by inosine and reversed by ZM241385 pre-treatment, suggesting the A2A receptor participation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of inosine on histopathological changes in allergic lung inflammation. Lungs tissues of immunized and challenged mice, pre-treated with adenosine receptors antagonists and treated with inosine, were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. a Basal naive group, not immunized or challenged with OVA. b OVA-immunized and challenged mice (allergic group). c OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated with the vehicle (Tween 20) used to administer the adenosine receptor antagonists and inosine. d, e OVA-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with A2 adenosine receptors antagonists and treated with inosine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). f OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated only with inosine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). g Epithelial cell proliferation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5 for each group. ***P < 0.001 when compared with the allergic control group (V); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B); +++P < 0.001 when compared with the inosine-treated group

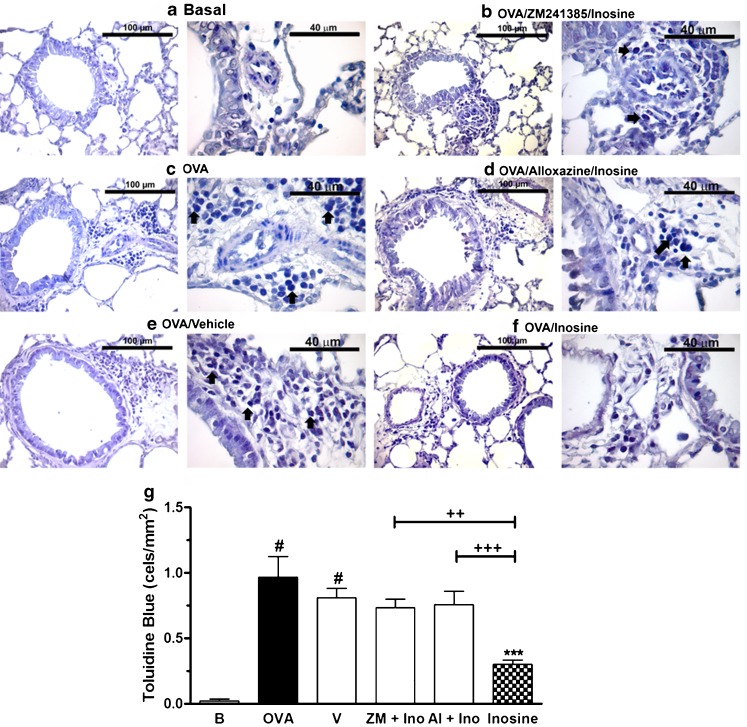

Accordingly, mast cells count were also increased in the peribronchial and perivascular areas of the airways of allergic mice stained with toluidine blue, but were not detected in lungs from basal group (Fig. 4a, c). The treatment with inosine reduced significantly the mast cell counting in allergic group (Fig. 4f), an effect reversed with ZM241385 and alloxazine pre-treatment (Fig. 4b, d, g).

Fig. 4.

Mast cell count in lung tissues of allergic mice treated with inosine. Lungs tissues of immunized and challenged mice, pre-treated with adenosine receptor antagonists and treated with inosine, were stained with toluidine blue. Some of the metachromatic mast cells were indicated with arrows. a Basal naive group, not immunized or challenged with OVA. b OVA-immunized and challenged mice (allergic group). c OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated with the vehicle (Tween 20) used to administer the adenosine receptor antagonists and inosine. d, e OVA-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with adenosine receptor antagonists and treated with inosine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). f OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated only with inosine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). g Mast cell count represented as cells per square millimetre. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5 for each group. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 when compared with the allergic control group (V); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B); ++P < 0.01; +++P < 0.001 when compared with the inosine-treated group

In a different set of experiments, the participation of A3 receptors in inosine effects was investigated by the pre-treatment with MRS3777, a selective adenosine A3 receptor antagonist. The administration of MRS3777 prevented completely the inosine effects against total cell count and against macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils cell count in the BALF (Fig. 5a–c). This additional data suggest that inosine might act through A3 receptors to reduce inflammation.

Fig. 5.

Effects of A3 adenosine receptor antagonist on inosine effects in the OVA-induced inflammation. Immunized mice were pre-treated with MRS3777, 30 min before inosine. The treatments were performed 30 min before the challenges. After 24 h, the total leukocyte counting (a) and the differential counting of macrophages (b), lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils (c) were performed in the BALF. B basal group not immunized, challenged or treated; OVA ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice; V ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with vehicle used to dilute the antagonists; MRS + Ino ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with MRS3777 and treated with inosine; Inosine ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with inosine. Each column represents the mean of the values obtained in five to eight animals, and the error bars indicate the SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with vehicle group (V); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B); +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 when compared with the inosine-treated group

Interaction of inosine with adenosine receptors and its effect on the ex vivo release of IL-4 and IL-5 in lungs

As shown in Fig. 6a, b, a significant increase in IL-4 and IL-5 levels was found in the supernatant of the lung tissue of allergic mice (OVA) and inosine treatment effectively prevented this IL-4 and IL-5 increase. Neither the A2A nor A2B adenosine receptor antagonist effectively modified inosine-induced reduced levels of IL-4 and IL-5 in lung tissue.

Fig. 6.

Effects of inosine on production of interleukin IL-4 and IL-5 cytokines by lung explants. The lungs of immunized and challenged mice, pre-treated with ZM241385 or alloxazine and treated with inosine, were removed and cultured for 24 h to measure the ex vivo release of IL-4 and IL-5 in lungs. B basal group not immunized, challenged or treated; OVA ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice; V ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with vehicle used to dilute the antagonists; ZM + Ino ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with ZM241385 and treated with inosine; Al + Ino ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice pre-treated with allozaxine and treated with inosine; Inosine ovalbumin-immunized and challenged mice treated with inosine. Each column represents the mean of the values obtained in five to eight animals, and the error bars indicate the SEM. ***P < 0.001 when compared with vehicle control group (V); #P < 0.001 when compared with the basal group (B)

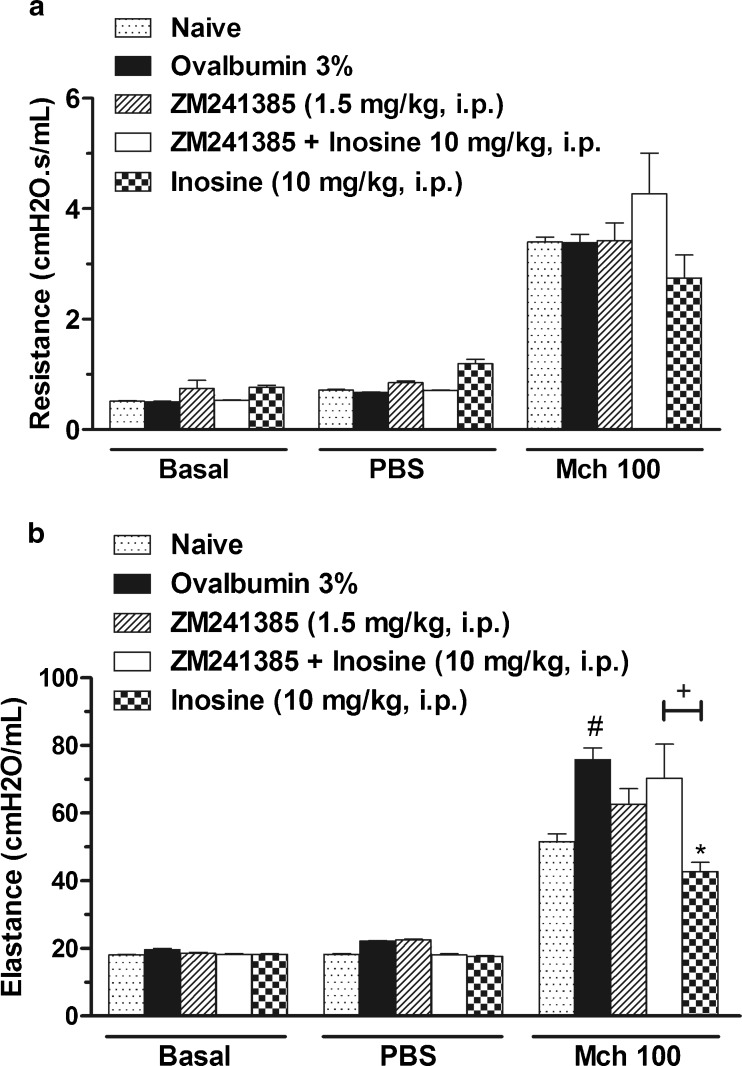

Inosine effects on bronchial responsiveness “in vivo”

After demonstrating that inosine reduce the allergic lung inflammation and that A2A adenosine receptor antagonist reversed this effect, we examined the effects of inosine treatment on MCh responsiveness in vivo. The lung resistance to methacholine at concentration of 100 mg/ml was not significantly increased in the ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized and challenged mice when compared to basal group (Fig 7a). However, significant augmentation of elastance was observed after methacholine challenge in allergic group (Fig. 7b). Inosine treatment reduced this effect, and the treatment with ZM241385 reversed the inhibitory effect of inosine. Additionally, the treatment only with ZM241385 did not cause any effect per se.

Fig. 7.

Effects of inosine treatment on airway responsiveness to methacholine (MCh) in vivo. Immunized mice were treated with ZM241385 or inosine or pre-treated with ZM241385 and treated with inosine and challenged with OVA, 30 min later. After 24 h, the airway resistance (a) and elastance (b) were measured in the presence of methacholine. Basal group represents mice not challenged with MCh; PBS group represent mice challenged with PBS and MCh 100 correspond to the group challenged with methacholine at concentration of 100 mg/ml. Dotted bars represent the basal group not immunized, challenged or treated; closed bars represent the allergic group treated with vehicle used to dilute the antagonist; hatched bars represent the allergic group treated with ZM241385; open bars represent the allergic group treated with ZM241385 plus inosine; chess bars indicate the allergic group treated with inosine. Each column represents the mean of the values obtained in five to six animals, and the error bars indicate the SEM. *P < 0.05 when compared with the vehicle group (V); #P < 0.05 when compared with basal group

Discussion

Asthma immunopathology is dominated by a T helper (Th) cell response skewed towards a Th2 cytokine/chemokine pattern that also involves airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells and tissue remodelling. The research on asthma over the past decade has expanded the complex repertoire involved in its pathophysiology to include inflammatory, immune and structural cells as well as a wide range of mediators [29].

Some studies have been shown that adenosine is a pro-inflammatory mediator involved in the pathogenesis of asthma [7], since recent research have demonstrated that elevated levels of adenosine induces bronchoconstriction and was found in the airways of patients with asthma [7, 30]. The bioavailability of adenosine is an important determinant of its biological functions and deleterious effects in the lung. Adenosine is quickly converted into inosine, by the enzyme adenosine deaminase, during inflammation, hypoxia or whenever the energy demand is greater [7, 8, 30, 31]. Therefore, to limit adenosine effects in lungs, the adenosine metabolism generates inosine that recently was reported to exert protective effects during airway inflammation [7, 15, 18, 21, 22, 25, 32]. Thus, in the present study, we evaluated the inosine effects in allergic lung inflammation.

Accordingly, inosine treatment before antigen challenge resulted in a diminished number of inflammatory cells in the BALF, characterized mainly by a reduction in macrophage, lymphocytes and eosinophil differential cell count, when compared with the allergic group, 24 h after antigen (OVA) challenge. This notion was confirmed by histological examination of lungs from inosine-treated mice. Notably, similar protective effects of inosine have been described in a model of acute lung injury, in which rodents are exposed to LPS [21]. In addition, an inosine analogue (INO-2002) demonstrated similar anti-inflammatory properties in an acute respiratory distress syndrome model [22]. In agreement, a recent study from our group have revealed that inosine significantly reduces pleural acute inflammation, reducing pleural leakage, neutrophil count, TNF-α and IL-1β levels in pleural exudates, an effect dependent on A2A adenosine receptor activation [23]. Because inosine exerts regulatory effects on immune response [5] and increased tissue inosine levels are quantified in the inflamed sites [4, 32], our data suggest that purines constitute a target pathway for the control of allergic asthma. To this end, our study speculates the interaction between inosine and adenosine receptors in our model. This approach relied on the hypothesis that the inosine anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by adenosine A2 receptors [5, 18, 27] and that the adenosine receptors A2A and A3 are targets of inosine in concanavalin A-induced liver damage and endotoxin-induced sepsis [4]. Our study shows that treatment of mice with the selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist, ZM241385, reversed the protective effect of inosine on the accumulation of cells, notably macrophages, in the BALF after OVA challenge. Conversely, blocking adenosine A2B receptors with alloxazine did not modify these effects of inosine. In agreement, the histological analysis of lung tissue stained with haematoxylin and eosin confirmed these results. Overall, these findings support our hypothesis that adenosine A2A receptors mediate the effects of inosine on the leukocyte recruitment observed in allergic lung disorders. Immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties observed after activation of A2A receptors in the airways are well documented. Indeed, it was recently shown that the treatment with CGS21680, a selective agonist of the adenosine A2A receptor, attenuates acute carrageenan-induced pleural and lung inflammation [33] and allergic pulmonary inflammation in rats [13]. Some studies also demonstrated that A2A receptor activation may cause suppression of the recruitment of T lymphocytes to the lungs [34, 35]. Additionally, increased expression of A2A adenosine receptors has been described in macrophages during the inflammatory process [36] and has been linked to the suppression of macrophage function and inhibition of immune-associated inflammation [36]. Accordingly, our results demonstrated that inosine controls macrophage access to lung compartments via a mechanism involving A2A receptors. Conversely, our data for ZM241385 were unable to identify the role of A2A receptors in lymphocyte recruitment. This data led us to hypothesize that inosine could, directly or indirectly through A2A adenosine receptors, modulate macrophage activation, decreasing lung inflammation. Moreover, the results obtained in this study demonstrated that the adenosine A3 receptors might also modulate the inosine effects. The functional role of adenosine A3 receptors in the lungs seems to be unclear, as both the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties of these receptors have been identified. Some studies have demonstrated that inosine and adenosine bind to A3 receptors and prime mast cell degranulation in “in vitro” [5, 20]. Conversely, adenosine A3 receptors seem to inhibit the activation and migration of eosinophils [5]. Our results corroborate with literature data and demonstrate that pre-treatment with MRS3777 reverted the inhibitory effects of inosine against eosinophils, lymphocytes and macrophages mobilization into lungs. Taking into account these evidences, we speculate that inosine can act through A2A and A3 receptors to reduce inflammation. This notion is in agreement with that reported by Otha and Sitkovisky [4], which showed that both A2A and A3 adenosine receptors were required for inosine to protect tissue, in a model of LPS-induced endotoxaemia.

Our results also demonstrated that inosine reduces mast cell recruitment to the lungs of allergic mice, an effect reversed by ZM241385 and alloxazine pre-treatment. Some studies have identified the expression of both adenosine A2A and A2B receptors in mast cells [37]. It has been proposed that the inosine precursor, adenosine, acting through these receptors, can respectively suppress or stimulate mast cells activation being the latter related with bronchoconstrictor effects [37]. In contrast, it is described that inosine has no effect on airway calibre, and it is suggested that bronchoconstriction is a response specific to adenosine [38]. These results suggest that the activation of adenosine A2A and A2B receptors is involved in the inosine modulation of mast cell mobilization into inflamed lungs. Taking into account the above-mentioned and that mast cells are able to elicit contraction of bronchial smooth muscle due to release of pro-inflammatory mediators [30, 39, 40], we further evaluate the effects of inosine in bronchial responsiveness induced by aerosolized MCh. In agreement with the previous results obtained here, our results showed that inosine treatment significantly prevented the augmentation of elastance induced by antigen challenge, an effect that was reversed by ZM241385, reinforcing the hypothesis that adenosine A2A receptors activation mediates inosine protective effects in allergic lungs, improving lung function.

Our data show that inosine significantly reduces the levels of IL-4 and IL-5 in lung tissue explants of allergic mice. Because Th2 cytokines such as those quantified in this study are related to recruitment of mast cells, maturation of eosinophils, IgE synthesis and cell mobilization in allergic asthma [29], and considering that elevated levels of inosine are found at inflamed sites [4, 32], we have inferred possible auto-control of allergic lung inflammation that might be mediated by purines, however, through a mechanism that seems to be independent of A2A or A2B receptor activation, since ZM241385 and alloxazine did not interfere with the effects of inosine on IL-4 and IL-5 levels.

Besides that inosine is reported to bind to adenosine receptors, other additional mechanisms were also described. Inosine may partially act by interfering with the activation of the nuclear enzyme poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase [41, 42], which was involved in the regulation of inflammatory processes in acute lung injury [42]. Inosine may also enhance endogenous antioxidant systems because inosine breakdown releases urate, a scavenger of oxyradicals and peroxynitrite [17, 41, 43]. Thus, we can not discard that these mechanisms are involved and contributes with inosine effects observed in the current study.

Conclusions

The results reported herein provide an experimental demonstration of inosine role in allergic inflammation and add information on the understanding of purinergic signalling in the airway. This study showed that inosine exerts an interesting effect in suppressing some of the classic features of allergic lung inflammation decreasing leukocytes migration to the lung that can be directly associated with Th2-cytokine, IL-4 and IL-5 release. In addition, the fact that some inosine effects were abolished by selective A2A and A3 antagonists suggests the possible involvement of these receptors in inosine activity. These findings expand the literature data and may be important to the understanding of purinergic pathways and the role of adenosine receptors in the pathogenesis of asthma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES); Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina (FAPESC), Programa de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais (REUNI); Programa Nacional de Cooperação Acadêmica (PROCAD) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Fernanda da Rocha Lapa, Email: fernandarlapa@yahoo.com.br.

Ana Paula Ligeiro de Oliveira, Email: apligeiro@gmail.com.

Beatriz Golega Accetturi, Email: beatriz.golega@gmail.com.

Helory Vanni Domingos, Email: helory_vanni@yahoo.com.br.

Daniela de Almeida Cabrini, Email: cabrini@ufpr.br.

Wothan Tavares de Lima, Email: wtavares@usp.br.

Adair Roberto Soares Santos, Phone: +55-48-37219352, FAX: +55-48-37219672, Email: adair.santos@ufsc.br, Email: adairrs.santos@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(3):413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caruso M, Holgate ST, Polosa R. Adenosine signalling in airways. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(3):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(4):527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez G, Sitkovsky MV. Differential requirement for A2a and A3 adenosine receptors for the protective effect of inosine in vivo. Blood. 2003;102(13):4472–4478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasko G, Sitkovsky MV, Szabo C. Immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects of inosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(3):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sitkovsky MV, Ohta A. The ‘danger’ sensors that STOP the immune response: the A2 adenosine receptors? Trends Immunol. 2005;26(6):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spicuzza L, Di Maria G, Polosa R. Adenosine in the airways: implications and applications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533(1–3):77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackburn MR. Too much of a good thing: adenosine overload in adenosine-deaminase-deficient mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24(2):66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cushley MJ, Tattersfield AE, Holgate ST. Inhaled adenosine and guanosine on airway resistance in normal and asthmatic subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;15(2):161–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb01481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oosterhoff Y, de Jong JW, Jansen MA, Koeter GH, Postma DS. Airway responsiveness to adenosine 5′-monophosphate in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is determined by smoking. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(3):553–558. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruso M, Varani K, Tringali G, Polosa R. Adenosine and adenosine receptors: their contribution to airway inflammation and therapeutic potential in asthma. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(29):3875–3885. doi: 10.2174/092986709789178055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortaz E, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Henricks PA. ATP and the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;638(1–3):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fozard JR, Ellis KM, Villela Dantas MF, Tigani B, Mazzoni L. Effects of CGS 21680, a selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist, on allergic airways inflammation in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;438(3):183–188. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Hashim AZ, Abduo HT, Rachid OM, Luqmani YA, Al Ayadhy BY, Alkhaledi GM. Intranasal administration of NECA can induce both anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory effects in BALB/c mice: evidence for A 2A receptor sub-type mediation of NECA-induced anti-inflammatory effects. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22(3):243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eltzschig HK. Adenosine: an old drug newly discovered. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(4):904–915. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trams EG, Lauter CJ. On the sidedness of plasma membrane enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;345(2):180–197. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liaudet L, Mabley JG, Soriano FG, Pacher P, Marton A, Hasko G, Szabo C. Inosine reduces systemic inflammation and improves survival in septic shock induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(7):1213–1220. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2101013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasko G, Kuhel DG, Nemeth ZH, Mabley JG, Stachlewitz RF, Virag L, Lohinai Z, Southan GJ, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Inosine inhibits inflammatory cytokine production by a posttranscriptional mechanism and protects against endotoxin-induced shock. J Immunol. 2000;164(2):1013–1019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahimian R, Fakhfouri G, Daneshmand A, Mohammadi H, Bahremand A, Rasouli MR, Mousavizadeh K, Dehpour AR. Adenosine A2A receptors and uric acid mediate protective effects of inosine against TNBS-induced colitis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;649(1–3):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin X, Shepherd RK, Duling BR, Linden J. Inosine binds to A3 adenosine receptors and stimulates mast cell degranulation. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(11):2849–2857. doi: 10.1172/JCI119833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liaudet L, Mabley JG, Pacher P, Virag L, Soriano FG, Marton A, Hasko G, Deitch EA, Szabo C. Inosine exerts a broad range of antiinflammatory effects in a murine model of acute lung injury. Ann Surg. 2002;235(4):568–578. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200204000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabley JG, Pacher P, Murthy KG, Williams W, Southan GJ, Salzman AL, Szabo C. The novel inosine analogue INO-2002 exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in a murine model of acute lung injury. Shock. 2009;32(3):258–262. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819c3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.da Rocha Lapa F, da Silva MD, de Almeida Cabrini D, Santos AR. Anti-inflammatory effects of purine nucleosides, adenosine and inosine, in a mouse model of pleurisy: evidence for the role of adenosine A(2) receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8(4):693–704. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sitkovsky MV. Use of the A(2A) adenosine receptor as a physiological immunosuppressor and to engineer inflammation in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65(4):493–501. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nascimento FP, Figueredo SM, Marcon R, Martins DF, Macedo SJ, Jr, Lima DA, Almeida RC, Ostroski RM, Rodrigues AL, Santos AR. Inosine reduces pain-related behavior in mice: involvement of adenosine A1 and A2A receptor subtypes and protein kinase C pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(2):590–598. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riffo-Vasquez Y, Ligeiro de Oliveira AP, Page CP, Spina D, Tavares-de-Lima W. Role of sex hormones in allergic inflammation in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(3):459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Proust B, Nahori MA, Ruffie C, Lefort J, Vargaftig BB. Persistence of bronchopulmonary hyper-reactivity and eosiniphilic lung inflammation after anti-IL-5 or IL-13 treatment in allergic BALB/c and IL-4Rα knockout mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:119–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orihara K, Dil N, Anaparti V, Moqbel R. What’s new in asthma pathophysiology and immunopathology? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4(5):605–629. doi: 10.1586/ers.10.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polosa R, Holgate ST. Adenosine receptors as promising therapeutic targets for drug development in chronic airway inflammation. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7(6):699–706. doi: 10.2174/138945006777435236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun CX, Zhong H, Mohsenin A, Morschl E, Chunn JL, Molina JG, Belardinelli L, Zeng D, Blackburn MR. Role of A2B adenosine receptor signaling in adenosine-dependent pulmonary inflammation and injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2173–2182. doi: 10.1172/JCI27303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia Soriano F, Liaudet L, Marton A, Hasko G, Batista Lorigados C, Deitch EA, Szabo C. Inosine improves gut permeability and vascular reactivity in endotoxic shock. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(4):703–708. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Impellizzeri D, Di Paola R, Esposito E, Mazzon E, Paterniti I, Melani A, Bramanti P, Pedata F, Cuzzocrea S. CGS 21680, an agonist of the adenosine (A2A) receptor, decreases acute lung inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;668(1–2):305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang S, Apasov S, Koshiba M, Sitkovsky M. Role of A2a extracellular adenosine receptor-mediated signaling in adenosine-mediated inhibition of T-cell activation and expansion. Blood. 1997;90(4):1600–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshiba M, Rosin DL, Hayashi N, Linden J, Sitkovsky MV. Patterns of A2A extracellular adenosine receptor expression in different functional subsets of human peripheral T cells. Flow cytometry studies with anti-A2A receptor monoclonal antibodies. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(3):614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia GE, Truong LD, Li P, Zhang P, Du J, Chen JF, Feng L. Adenosine A2A receptor activation and macrophage-mediated experimental glomerulonephritis. FASEB J. 2008;22(2):445–454. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8430com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polosa R. Adenosine-receptor subtypes: their relevance to adenosine-mediated responses in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(2):488–496. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01132002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livingston M, Heaney LG, Ennis M. Adenosine, inflammation and asthma—a review. Inflamm Res. 2004;53(5):171–178. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holgate ST. Pathogenesis of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(6):872–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):445–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virag L, Szabo C. Purines inhibit poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation and modulate oxidant-induced cell death. FASEB J. 2001;15(1):99–107. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0299com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liaudet L, Pacher P, Mabley JG, Virag L, Soriano FG, Hasko G, Szabo C. Activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a central mechanism of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(3):372–377. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2106050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker BF, Reinholz N, Ozcelik T, Leipert B, Gerlach E. Uric acid as radical scavenger and antioxidant in the heart. Pflugers Arch. 1989;415(2):127–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00370582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]