Background: The role of ROS in FcγR signal transduction is unknown.

Results: Deletion of gp91phox results in decreased IL-6 production and reduced Akt activation following FcγR engagement by immune complexes.

Conclusion: Production of ROS via NOX2 is required for IL-6 production following FcγR engagement of immune complexes.

Significance: ROS serves as a second messenger to facilitate FcγR signal transduction.

Keywords: Akt, FC Receptors, Macrophages, NADPH Oxidase, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Francisella tularensis

Abstract

Activation of the FcγR via antigen containing immune complexes can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species, which are potent signal transducing molecules. However, whether ROS contribute to FcγR signaling has not been studied extensively. We set out to elucidate the role of NADPH oxidase-generated ROS in macrophage activation following FcγR engagement using antigen-containing immune complexes. We hypothesized that NOX2 generated ROS is necessary for propagation of downstream FcγR signaling and initiation of the innate immune response. Following exposure of murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) to inactivated Francisella tularensis (iFt)-containing immune complexes, we observed a significant increase in the innate inflammatory cytokine IL-6 at 24 h compared with macrophages treated with Ft LVS-containing immune complexes. Ligation of the FcγR by opsonized Ft also results in significant ROS production. Macrophages lacking the gp91phox subunit of NOX2 fail to produce ROS upon FcγR ligation, resulting in decreased Akt phosphorylation and a reduction in the levels of IL-6 compared with wild type macrophages. Similar results were seen following infection of BMDMs with catalase deficient Ft that fail to scavenge hydrogen peroxide. In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that ROS participate in elicitation of an effective innate immune in response to antigen-containing immune complexes through FcγR.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS),3 first thought to only be toxic byproducts of cellular function, are now understood to play a critical role in a multitude of cellular processes (1). In macrophages, ROS generation is known to be used to help destroy phagocytosed bacteria, cellular debris, and foreign material (2, 3). One major source of ROS in macrophages is the phagocytic NADPH oxidase complex (NOX2), which consists of a membrane-bound fraction (gp91phox and p22phox) and an array of cytoplasmic factors (p40phox, p47phox, p67phox, and Rac) that translocate to the membrane resulting in formation of a primed and active NOX2 complex (4–7). ROS production occurs following FcγR cross linking (8, 9), during phagocytosis (2, 10), and engagement of TLR4 or TLR2 (11–13). Superoxide radicals (O2⨪) generated by NOX2 spontaneously dismutate into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at a rate of ∼105 m s−1 at pH 7, with H2O2 having a significantly longer half-life and thought to be the primary signaling oxidant acting within the cell (3). H2O2 has been shown to act as a intracellular secondary messenger, able to interact with signaling proteins and transcription factors that control diverse aspects of cellular function (reviewed by Kishimoto here (14)).

FcγR cross linking signals the release and activation of NF-κB, a major cellular transcription factor that regulates macrophage activation and production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNFα, and IL-12 (15). One pathway known to be downstream of the FcγR and sensitive to changes in the redox state of the cell is the PI3K/Akt pathway (16). Cross linking of the FcγR leads to activation of Src family kinases, Syk recruitment to the signaling complex, and PI3K activation, resulting in accumulation of the phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the membrane (17). PI3K activation is known to be antagonized by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), a dual lipid protein phosphatase whose activity is impaired following S-nitrosylation or oxidation by H2O2 of its active site cysteine (18). PIP3 accumulation leads to the recruitment of a wide array of kinases to the membrane, including Akt and PDK1, through their PIP3 binding pleckstrin homology domains (17). Akt is a critical cellular kinase, regulating actin remodeling, cell survival, and NF-κB-dependent gene transcription (19).

NF-κB was first shown by Libermann and Baltimore to bind the upstream promoter region of the IL-6 gene and is required for maximal IL-6 production (20). The IL-6 gene contains dual NF-κB binding sites, which are critical for effective transcription, and point mutations of these regions significantly reduces NF-κB binding and IL-6 transcription (20). While ROS have been shown to impact NF-κB-based signaling, the underlying mechanism is unclear. Increased intracellular ROS have also been shown to directly influence the NF-κB activation by inducing phosphorylation and inhibition the NF-κB regulator IκBα (21). In addition, H2O2 can act, not to activate NF-κB directly, but rather to alter NF-κB activation in response to other stimuli such as TNF-α (22).

Previous work from our laboratory established that PTEN is maintained in its reduced and antagonistic state following infection with the Gram-negative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis (23). Mellilo et al. established that Francisella LVS restricts cell signaling and delay bacterial recognition by the host cell and engagement of the innate immune response. The preservation of PTEN function by F. tularensis leads to a significant reduction in the ability of human primary macrophages to produce IL-6 (23). This observed phenotype was reversed upon macrophage infection with LVS lacking the bacterial H2O2-scavenging enzyme catalase (ΔkatG). Increased IL-6 expression has recently been reported to correlate with resistance to primary microbial infection. IL-6 and its effect on the innate and adaptive immune response have been shown to be required for protection against Candida, Yersinia enterocolitica, L. monocytogenes, and M. tuberculosis (24–28) infection, as well as F. tularensis (29). The role of IL-6 during generation of the immune response is multi-faceted, and elicits production of acute phase proteins, T cell maturation, B cell differentiation, and germinal center formation (14, 30).

To define the role of FcγR-dependent ROS in macrophage IL-6 production, we employed distinct F. tularensis containing immune complexes, each with a varying ability to scavenge ROS. This allowed us to use Ft-containing immune complexes to study the rate of ROS production, potential changes in FcγR-mediated cell signaling, and IL-6 cytokine secretion in primary murine macrophages. Here we report that macrophages which lack a functional NOX2 complex show reduced Akt signaling and produce significantly less IL-6 following FcγR cross linking by immune complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Media

F. tularensis LVS (ATCC 29684; American Type Culture Collection) strain was provided by Karen Elkins (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, MD). The catalase mutant (ΔkatG) was kindly provided by Dr. Anders Sjöstedt. Both strains of F. tularensis were cultured on chocolate agar plates and resuspended in cell culture medium at 2 × 109 total bacteria/ml as determined by optical density. Bacterial concentrations were confirmed by serial dilution on chocolate agar. For experiments utilizing nonviable bacteria, F. tularensis LVS was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 2 × 108 bacteria/ml and inactivated by resuspension in a 4% formaldehyde solution for 20 min, followed by multiple washes before infection (31). Treatment led to >99% killing, which was confirmed by plating on chocolate agar. Further description of the inactivation protocol can be found in Rawool et al. (31).

Generation of Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages

Adult C57Bl/6 mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) and gp91phox knock-out mice (B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din/J, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were obtained for generation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) used in all experiments. BMDMs were isolated and differentiated as previously described (32).

Western Blot Analysis

Macrophages were infected at a MOI of 100 for all experiments. At each time point post infection (0–60 min), macrophages were lysed in RIPA buffer with added protease inhibitors (cOmplete mini (Roche), PMSF, Na-Orthovanadate, NaF). Proteins were separated by size and charge on a 12% SDS-page electrophoresis gel before transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with TBST + 5% BSA or Blotto + 10% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-Akt antibodies used to measure phosphorylation at threonine residue 308 (Cell Signaling 4056), or total Akt (Cell Signaling 9272) were purchased from Cell Signaling. Blotting for β-actin (Invitrogen AM4302) was used as a loading control in all blotting experiments.

Immune Complex Formation

Glass beads two microns in diameter were coated with BSA and opsonized using 1 μg/ml of anti-BSA antibody as previously described by Loegering and Lennartz (33). Opsonization of Francisella bacteria was performed by incubating 1 μg/ml of an anti-Francisella LPS antibody (Fitzgerald 10-F02B) with 109 bacteria while rocking for 1 h at 4 °C. Otherwise, bacterial immune complexes were constructed exacted as described in previously (31).

Cytokine Analysis

BMDMs were plated at one hundred thousand cells per well in a 96-well plate overnight in BMDM media. The next day, cells were stimulated with immune complexes at an MOI of 100 for 2 h in serum-free media. Cells were then washed for one hour with cell culture media containing 75 μg/ml gentamicin (Cellgro 30-005-CR) to wash and inactivate extracellular bacteria still present. Gentamicin-containing media was then replaced with non-antibiotic-containing cell culture media for overnight incubation. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 24 h poststimulation and frozen until analysis. Levels of IL-6 were measured using a Bio-Plex 200 System, and data were quantified using Bio-Plex manager 3.0 software. Quantitation of IL-6 was also measured using cytometric bead array mouse flex sets (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed using a FACSArray bioanalyzer and FCAP Array software. The results of both analyses are expressed as pg/ml.

IL-6 production was also measured in some studies by ELISA (ebioscience). Optical density values from the colorimetric assay were quantified and compared with a standard curve generated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement/Inhibition of ROS Production by NADPH Oxidase

Detection of ROS production in in vitro cultured BMDMs was modified from Tain et al. (34). BMDMs were washed twice in cold DPBS-luminol media consisting of 20 mm dextrose, 20 units/ml horseradish peroxidase, and 50 μm luminol for 10 min prior to addition of stimulant. Upon addition of stimulants on ice, BMDMs were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C before addition of the samples to the Perkin Elmer Victor V3 1420 multilabel luminometer at 37 °C. Chemiluminescence (CL) was measured and quantified as counts per second (CPS) using Wallac 1420 manager software.

Inhibition of NADPH Oxidase activity was accomplished by treatment of BMDMs with 250 μm apocynin (Sigma W508454). Apocynin was added to cell culture media for 2 h pre-stimulation, during immune complex stimulation, and in cell culture media during overnight incubation. In experiments which included the addition of catalase, PEG-Catalase (Sigma C4963) was resuspended in 1× DPBS before addition to assay media containing preformed immune complexes.

Immunofluorescence Staining

BMDMs were cultured on glass coverslips overnight in BMDM differentiation media. The following day, macrophages were stimulated with iFtmAb immune complexes at an MOI 100 for 0 and 15 min. At each time point, cover slips were removed from media and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in DPBS. Fixed coverslips were stained with antig-IgG2a-Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250 dilution), permeabilized with 0.02% saponin, and stained with anti-IgG2a-Alexa Fluor 594 (1:250 dilution). Anti-IgG2a staining was performed for 1 h each before excess antibody was washed away using fixative containing media. Coverslips were mounted onto slides using FluoroGel II containing DAPI (EMS). Images were taken using an Olympus 1X81 microscope and Fluoview FV1000 laser. Images were analyzed using Olympus Fluoview FV10-ASW software.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using GraphPad 5.03 statistical software program. Where indicated, statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student's t test. p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

NOX2 Is Necessary for FcγR-mediated IL-6 Production in Macrophages

Engagement of the FcγR is known to result in macrophage production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNFα (15, 35), which play a role in the initial control of infection and subsequent initiation of immune memory in mice and humans (36, 37). Ligation of the FcγR by immune complexes also results in the production of ROS (8, 9), which works within phagocytic vesicles to assist in the break down and neutralization of pathogens or foreign antigens. ROS, specifically H2O2, has also been shown to act as a secondary messenger, reacting with active site cysteines in both kinases and phosphatases known to be downstream of the FcγR, resulting in their activation or inhibition, respectively (16). Thus, efficient H2O2 detoxification by receptor bound ligands may limit signals downstream of FcγR engagement restricting macrophage function. LVS infection has been reported to directly reduce the steady-state levels of hydrogen peroxide within a macrophage (23). However, paraformaldhyde inactivation of LVS renders the bacteria metabolically inactive and thus incapable of scavenging ROS. Opsonization of iFt has already shown to be an effective way to target antigen to the FcγR and induce protection against virulent type A infection (31). Using the same opsonization strategy, we were therefore capable of generating both LVS and iFt immune complexes able to bind the FcγR, which would either be able or unable to scavenge ROS produced following FcγR cross linking. Therefore, we sought to use these tools to determine the relationship between FcγR engagement, ROS production, and IL-6 secretion.

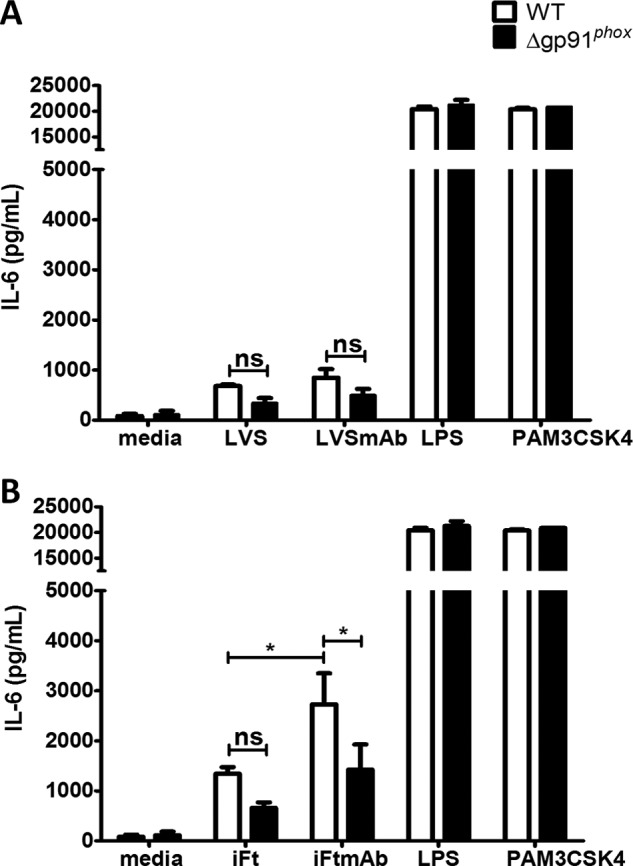

We first stimulated wild-type BMDMs with live Ft LVS or iFt for 2 h and IL-6 production was measured at 24 h post-stimulation. Compared with LVS stimulated macrophages, iFt stimulated WT BMDMs to produced ∼2-fold more IL-6 (p < 0.05). This difference is most likely due to the inherent loss of enzymatic function used by Ft to scavenge ROS and otherwise manipulate host macrophage activation following infection. Simultaneously, we stimulated macrophages with opsonized LVS (LVSmAb) and iFt (iFtmAb) to study the effect FcγR targeting of live versus inactivated bacteria would have on IL-6 production. Stimulation with LVSmAb results in no change in IL-6 production compared with non-opsonized LVS (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1A). However, stimulation of WT BMDMS with iFtmAb generates a ∼1.5-fold increase in the level of IL-6 production over iFt alone (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that stimulation of macrophages with iFt display a robust increase in IL-6 production relative to LVS and opsonization further enhances IL-6 production.

FIGURE 1.

Loss of gp91 protein attenuates IL-6 production in macrophages. WT and gp91phox KO BMDMS were stimulated with LVS (A), iFt (B), or bacteria opsonized with 1 μg of monoclonal anti-Ft LPS antibody. Macrophages were also stimulated with LPS, PAM3CSK4, or media alone as positive and negative controls. Supernatants were analyzed for IL-6 at 24 h poststimulation by Lumenix bead array. These data are the result of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Nonsignificant differences (ns) represent a p value >0.05. Asterisks (*) represent a p value <0.05.

To determine the contribution of NOX2 during FcγR-mediated IL-6 production, gp91phox KO BMDMs, which lack the catalytic subunit of the NOX2 complex, were stimulated with both opsonized and unopsonized bacteria and IL-6 production monitored. Stimulation of gp91phox KO BMDMs with LVSmAb did not result in increased production of IL-6 compared with LVS stimulated controls (Fig. 1A). Stimulation of gp91phox KO BMDMs with iFt or iFtmAb, however, results in a statistically significant reduction in the levels of IL-6 production when compared directly to the levels seen in WT BMDMs (Fig. 1B). WT and gp91 KO BMDMs were also stimulated with Escherichia coli LPS (a TLR4 ligand) or PAM3CSK4 (a TLR2/1 ligand), to confirm that IL-6 production was not compromised by the lack of gp91phox. No difference was found in the ability of either WT or gp91phox KO BMDMs to produce high levels of IL-6 upon LPS or PAM3CSK4 stimulation. Taken together, these data establish a significant role for gp91phoxand therefore the NOX2 complex in the production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 following binding of antigen-containing immune complexes to the FcγR in macrophages.

Immune Complexes Elicit FcγR-driven, NOX2-dependent ROS Production following FcγR Binding

The results in Fig. 1 show that FcγR-activated macrophages lacking gp91phox and thus a functional NOX2 complex produce significantly less IL-6 compared with WT cells. Our next query was to determine if the observed levels of inflammatory cytokine production were associated with ability of macrophages to produce ROS following FcγR cross linking. To measure ROS production in real-time, we employed the cell permeable redox-sensitive chemiluminescence compound luminol (38). Luminol chemiluminescence is not specific for the direct detection of the superoxide radical generated by NOX2, but is instead oxidized by its spontaneous breakdown product and known second messenger H2O2 (38, 39). Real-time quantitation of emitted light directly correlates to the levels of macrophage produced H2O2 and indicates the kinetics of ROS production following FcγR engagement. To confirm that NOX2 serves as the source of ROS following FcγR ligation, we measured the rate of ROS production for the first 40 min following FcγR cross linking, using both bacterial and non-bacterial immune complexes.

Resting BMDMs were stimulated with non-bacterial immune complexes consisting of murine anti-BSA coated BSA-conjugated glass beads. After an initial lag period, we detected a significant spike in ROS production by WT BMDMs stimulated with opsonized beads and the non-opsonized bead controls (Fig. 2A). WT BMDMs stimulated with non-opsonized beads induced a detectable luminol signal, ∼2.5-fold higher than background levels seen in media alone controls (Fig. 2A). The low level of oxidant production following stimulation with non-opsonized beads has been reported previously and is most likely due to non-FcγR-mediated phagocytosis of the unopsonized particle (27).

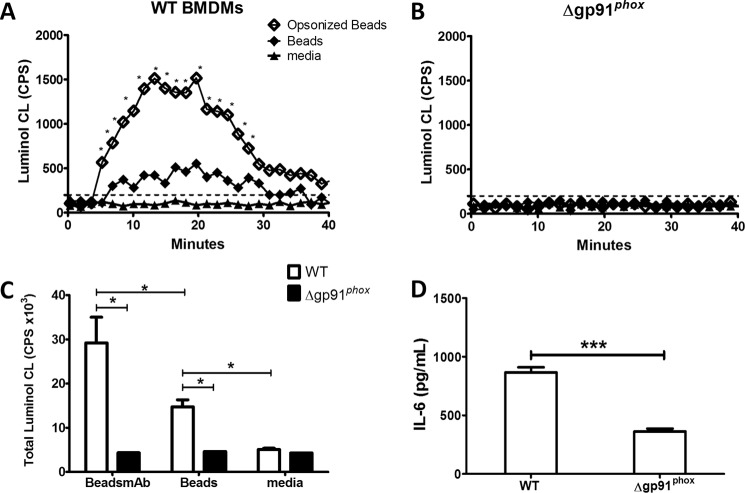

FIGURE 2.

Production of ROS following FcR engagement of bead immune complexes requires NOX2. Wild-type (A) or gp91 KO (B) BMDMs were stimulated with BSA-coated beads or anti-BSA opsonized BSA-coated beads (Beads+mAb). Real-time kinetics of luminol oxidation following stimulation of WT BMDMS (A) and gp91phox KO BMDMs (B) at 37 °C over the course of 40 min. C, total ROS production in WT and gp91phox KO BMDMs was calculated by measuring the area under the curve in A and B. D, loss of gp91phox results in significant drop in IL-6 production following stimulation of BMDMs with Beads+mAb as measured by ELISA. These data show one representative experiment of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Dashed lines represent luminol assay limit of detection. Asterisks (*) represent a p value <0.05, (***) represents p < 0.001.

The addition of opsonized beads to gp91phox KO BMDMS failed to induce any detectable chemiluminescence above the limit of detection over the measured time course (Fig. 2B), confirming that NOX2 is the primary source of ROS following FcγR ligation in macrophages and that the chemiluminescence signal detected is not generated from other cellular sources of ROS production such as the mitochondria. Quantitation of the total chemiluminescence signal confirms that cross-linking of the FcγR generates significantly greater amounts of ROS compared with non-FcγR mediated binding and phagocytosis of our non-bacterial immune complex (Fig. 2C).

Furthermore, following stimulation with Beads+mAb, gp91phox KO BMDMs produced significantly less IL-6 than WT BMDMs (Fig. 2D). Thus, data presented in Figs. 1 and 2 show for the first time that macrophages which lack the ability to produce NOX2 dependent ROS display a decreased capacity to produce IL-6 upon FcγR engagement. These data were generated using immune complexes devoid of bacterial ligand and provides strong evidence that ROS acts as a necessary secondary messenger to activate the cell following FcγR cross linking.

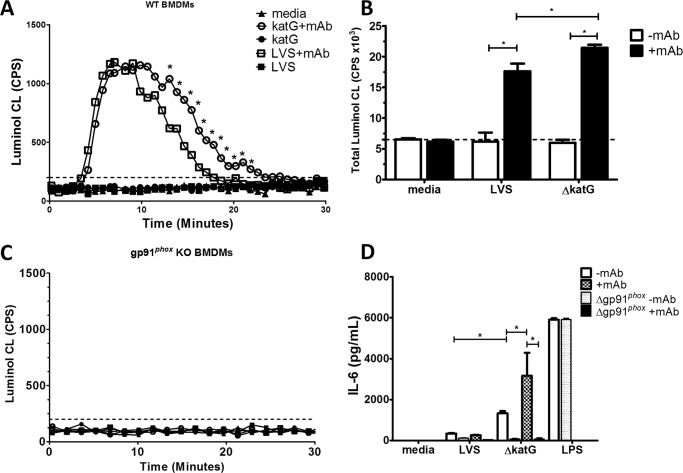

We next employed the LVSmAb and iFtmAb preparations exhibited in Fig. 1 to examine the rate of ROS production following FcγR engagement with pathogen-containing immune complexes. Stimulation with LVSmAb produces a sharp increase in ROS production with a maximal response within the first 10 min post-stimulation which returned to background levels after 20 min. Addition of iFtmAb induced a similar profile of luminol oxidation as that of LVSmAb, with distinct kinetics of both intensity and duration. While the rate of iFTmAb luminol oxidation was similar to that of LVSmAb stimulated macrophages, both the peak intensity and duration of the response are distinct (Fig. 3A). iFtmAb stimulated BMDMs produced ROS for a significantly longer period of time, generating a detectable signal for 30 min post-stimulation. Interesting, over the time course of which ROS production was measured, stimulation of WT BMDMs with LVSmAb and iFtmAb produced equal amounts of ROS (Fig. 3B). However, the kinetics of production differed significantly between stimulation with the two immune complexes. LVSmAb elicited a short yet strong luminol-signal which terminated 20 min poststimulation. iFtmAb complexes elicited a less robust ROS signal than LVSmAb, but ROS production was maintained longer, returning to background after 30 min post stimulation (Fig. 3A).

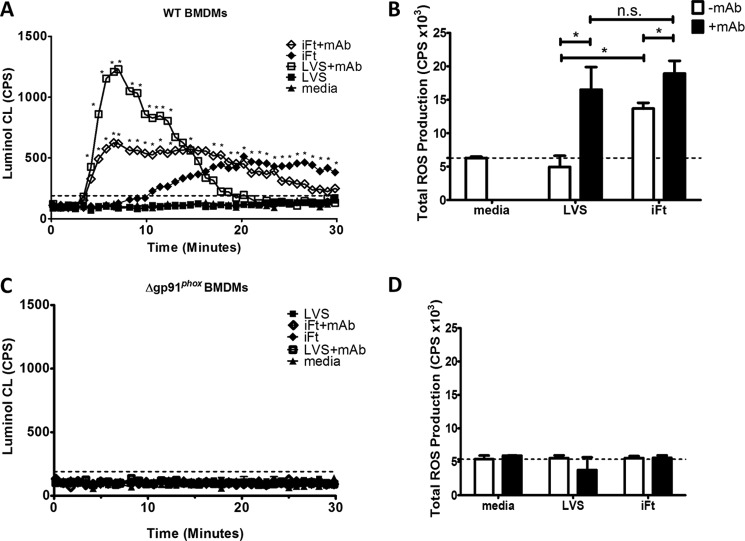

FIGURE 3.

Production of ROS following FcR engagement of Ft immune complexes requires NOX2. Wild-type (A and C) or gp91 KO (B and D) BMDMs were stimulated with live or inactivated bacterial immune complexes. The levels of oxidized luminol were measured at 45-s intervals in real-time to detect the production of ROS following Fc Receptor cross linkage. A and B, intensity of light produced from the oxidation of luminol was plotted for each time point for 40 min following binding at 4 °C and incubation at 37 °C in wild-type BMDMs. C and D, total ROS production in WT BMDMs was measured by calculating the area under the curve for each experimental condition. These data are the result of at least three independent experiments. In all panels, error bars represent the S.E. Dashed lines represent luminol assay limit of detection. Asterisks (*) represent a p value <0.05.

The addition of either opsonized LVS or iFt to gp91phox KO BMDMs failed to elicit any detectable ROS production (Fig. 3, C and D), consistent with the results observed using non-bacterial immune complexes shown in Fig. 2B. LVSmAb and iFtmAb immune complexes also failed to elicit any detectable level of ROS production in the gp91phox KO BMDMs. Most importantly, these data confirm that the entirety of ROS production following FcγR cross linking is NOX2-dependent.

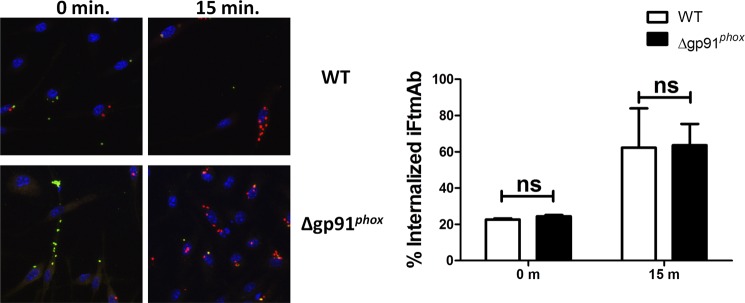

The difference in kinetics of ROS production seen between LVSmAb and iFtmAb could potentially be due to changes in the overall rate of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. Analysis of binding and internalization kinetics of Ft immune complexes (Fig. 4) show no difference in the rates by which iFtmAb immune complexes are phagocytosed in WT and gp91phox KO BMDMs.

FIGURE 4.

Deletion of NOX2 does not inhibit phagocytosis of Ft containing immune complexes. Wild-type or gp91phox KO BMDMS were incubated with iFtmAb immune complexes. At each time point, macrophages were fixed and stained for extracellularly bound iFtmAb the with anti-IgG2a-Alexa 488, then permeabilized and stained for intracellular bacteria with anti-IgG2a-Alexa 594 (left). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Percentage of internalized iFtmAb at the 0 m and 15 m time point were quantified. Data shown represent two independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Nonsignificant differences (ns) represent a p value >0.05.

The data in this study support the conclusion that the prolonged production of ROS following FcγR engagement contribute to higher level macrophage IL-6 production. Based on our observations presented in Figs. 1 and 3, prolonged ROS production correlates with high levels IL-6 production following FcγR cross linking with Ft immune complexes. Therefore, taken as a whole, these data show NOX2-dependent ROS are required for the downstream production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6.

Extracellular Scavenging of ROS Results in Decreases IL-6 Production following FcγR Cross Linking

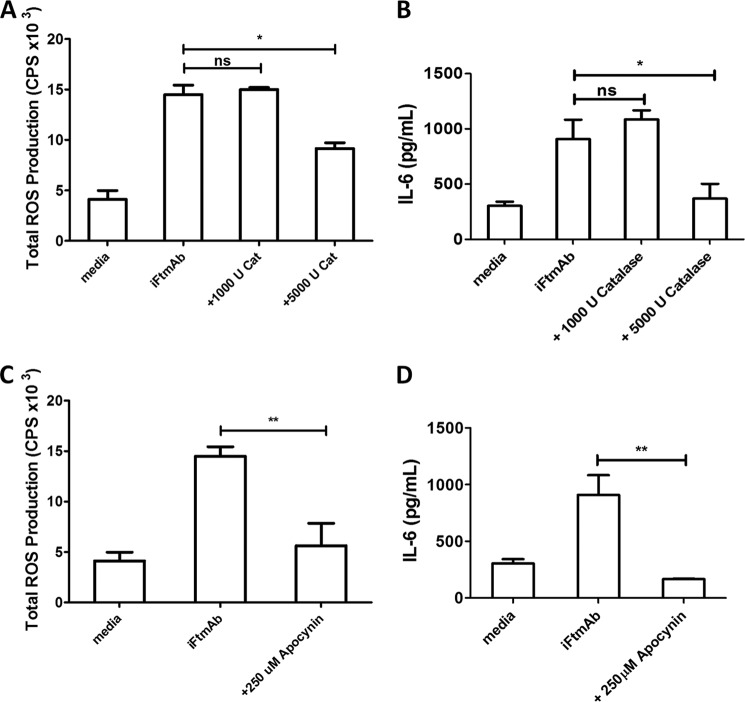

ROS generated by activation of the NOX2 complex are vectorially released into the lumen outside the cell, or into phagosomal compartments. We next evaluated the impact of scavenging vectorially released ROS or complete pharmacological inhibition of the NOX2 complex on FcγR-mediated ROS and IL-6 production. Addition of exogenous catalase, a highly specific H2O2 detoxifying enzyme, significantly reduced the overall production of ROS following stimulation with iFtmAb immune complexes (Fig. 5A). High level catalase concentrations decreased ROS production by ∼40% as monitored by luminol assay. This reduction in ROS production, though not complete, was associated with a failure in the IL-6-producing capacity of WT macrophages in response to FcγR by iFtmAb immune complexes (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Blockage of ROS following FcγR cross-linkage reduces Akt activation and IL-6 production in macrophages. WT BMDMs were treated with the NOX2 inhibitor Apocynin prior to and during stimulation with Ft containing immune complexes. Total Production of ROS was measured by luminol assay over the course of the first thirty minutes post stimulation with iFtmAb in the presence of PEG-Catalase (A) or apocynin (C). The effects of catalase (B) and apocynin (D) on the ability of WT BMDMs to produce IL-6 24 h poststimulation were collected and measured by luminex assay Data shown from at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Asterisks represent a p value <0.05 (*) or <0.01 (**), respectively.

In parallel, we chose to inhibit NOX2 mediated ROS production with the selective inhibitor apocynin. Apocynin is thought to competitively inhibit formation of the NOX2 complex by preventing effective electron transfer from NADPH to the gp91subunit. Apocynin treatment severely impaired FcγR-dependent ROS release (Fig. 5C). The apocynin-dependent inhibition of ROS was also accompanied by a loss in the macrophages ability to produce IL-6 (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data confirm that FcγR-generated ROS, specifically H2O2, is required to drive IL-6 production in macrophages following FcγR cross-linking.

Lack of gp91phox Results in Reduced Phosphorylation of Akt

Our findings suggest immune complex engagement of FcγR mediates production of ROS in a NOX2 dependent manner, which in turn plays a role in stimulation of macrophage IL-6 production. This led us to investigate the role ROS (specifically H2O2) plays in regulating downstream FcγR signals that ultimately lead to IL-6 production. Engagement of the activating FcγR is causally linked to activation of PI3K via Syk binding to the FcγR immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM). Activation of PI3K leads to accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3) in the cytoplasmic membrane, recruitment of PDK1 and direct phosphorylation of Akt at residue Thr-308 to further propagate signaling. Akt is a known upstream regulator of NF-κB activation, directly controlling the phosphorylation of IKKB and liberation of NF-κB from the chaperone, allowing for nuclear translocation and induction of gene expression (40).

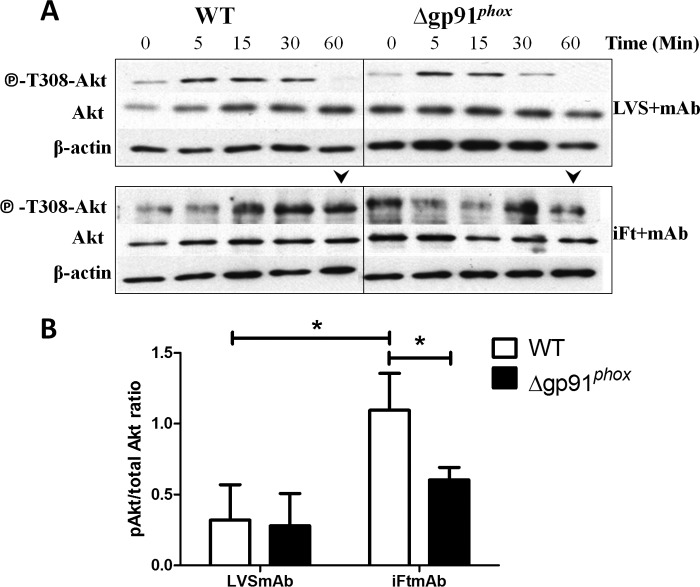

Building upon previous findings (23), we investigated the effect FcγR-mediated ROS production on the level of Akt phosphorylation following immune complex stimulation. In WT BMDMs, stimulation with LVSmAb complexes leads to a transient phosphorylation of Akt T308 at 15 min postinfection, decreasing significantly by 60 min post-infection (Fig. 6A). Stimulation with iFtmAb resulted in detectable Akt phosphorylation at 30 min p.i. which continued out to 60 min p.i. (Fig. 6A). Direct comparison of phospho-Akt T308 levels at 60 min p.i. reveals an increase in iFtmAb induced Thr-308 phosphorylation compared with stimulation with LVSmAb (Fig. 6B). As Ft is known for its ability to scavenge ROS intracellularly thus preventing the oxidation of PTEN (23), this observation is consistent with previously reported effects of Ft infection upon Akt phosphorylation (23). Simultaneous stimulation of gp91phox KO BMDMs with iFtmAb resulted in reduced phoso-Akt T308 at both the 30 min and 60 min time point compared with levels seen in WT BMDMs (Fig. 6B). These data establish a causal link between functional NOX2, its ability to generate H2O2, and effective inflammatory signaling downstream of the FcγR.

FIGURE 6.

Downstream activation of Akt following Fcγ receptor cross linking is reduced in NOX2-deficient macrophages. WT and gp91 KO BMDMs were stimulated with opsonized Ft LVS or iFt for up to one hour. A, at the time points shown above, cells were lysed and levels of phosphorylated Akt at tyrosine residue 308 compared with the level of total cellular Akt were measured by Western blot. Results from one independent and representative experiment are shown in A. B, ratio of phosphorylated Akt to total Akt at 60 m post-stimulation was analyzed by densitometry. Results shown are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Asterisks (*) represent a p value <0.05.

Stimulation of Macrophages with Antioxidant-deficient Bacteria Enhances IL-6 Production in a NOX2-dependent Manner

F. tularensis lacking antioxidant genes (specifically bacterial catalase, ΔkatG) elicit stronger IL-6 and TNFα production from macrophages compared with LVS (23). These bacteria scavenge H2O2 less efficiently than LVS, but are still able to detoxify superoxide (23, 41, 42), while iFt is incapable of mediating due to its inactivated state. Expanding this observation to our current work, we used antioxidant-deficient F. tularensis to determine if reduction of bacterial ROS scavenging effects IL-6 production by macrophages following stimulation (Fig. 7). Macrophages stimulated with ΔkatGmAb generated equivalent levels of ROS to samples stimulated with LVSmAb during the initial 10 min following stimulation (Fig. 7A). There was then a marked decrease in the level of ROS produced by macrophages stimulated with LVSmAb, while macrophages stimulated with ΔkatGmAb showed a prolonged level of ROS production (Fig. 7A). This prolonged level of ROS production suggests that the LVS, when in close proximity to the cell surface following binding to FcγR, are able to detoxify the localized burst of hydrogen peroxide more efficiently, reducing ROS production (Fig. 7B). Consistent with this idea, stimulation of gp91phox KO BMDMs with ΔkatGmAb immune complexes does not result in the production of detectable levels of ROS (Fig. 7C). The prolonged ROS production seen following ΔkatGmAb stimulation coincided with a significant increase in IL-6 production in WT BMDMs at the 24 h time point (Fig. 7D). The lack of ROS production seen in Fig. 7B also coincided with a significant decrease in IL-6 production in gp91phox KO BMDMs, further supporting the idea that prolonged ROS production is playing a direct role in IL-6 production.

FIGURE 7.

Antioxidant-deficient bacteria induce significantly more IL-6 in a NOX2-dependent manner. WT and gp91phox KO BMDMS were stimulated with Francisella LVS or ΔkatG alone or opsonized with 1 μg monoclonal anti-Ft LPS antibody. A, real-time production of ROS as measured by chemiluminescence following WT BMDM stimulation using LVSmAb or ΔkatGmAb immune complexes. B, total ROS production was quantitated by calculating the area under the curve in A. C, increased levels of ROS are dependent on gp91phox, as Δgp91phox BMDMs do not produce a detectable level of ROS following stimulation with ΔkatGmAb immune complexes. ΔkatGmAb immune complexes result in significantly higher levels of total luminol chemiluminescence. D, supernatants were analyzed for IL-6 at 24 h poststimulation by CBA. ΔkatG and ΔkatGmAb elicit significant higher levels of IL-6 in WT BMDMs compared with LVS or LVSmAb infected controls. Data presented in A and C representative figures of at least three independent experiments. Data presented in panels B and D represent at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Dashed lines in A and B represent luminol assay limit of detection. Asterisks (*) represent a p value <0.05.

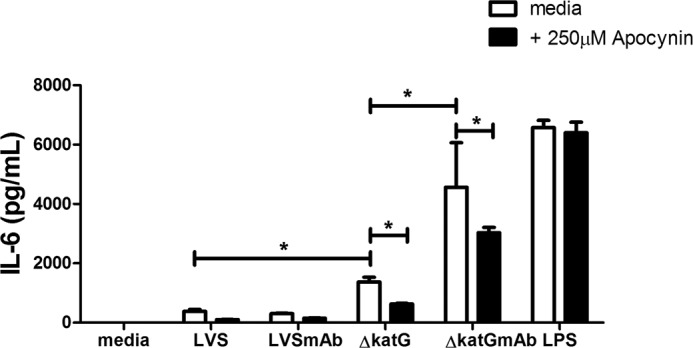

Finally, we pretreated macrophages with apocynin or media alone before addition of LVSmAb or ΔkatGmAb immune complexes. Apocynin treatment did not result in a reduction of IL-6 production following LVSmAb stimulation (Fig. 8). However, in the presence of apocynin, stimulation with ΔkatG or ΔkatGmAb results in a 30% reduction in IL-6 production 24 h poststimulation (Fig. 8). Consistent with the data presented in Figs. 1 and 5, Fig. 7 shows evidence that pharmacological inhibition of the NOX2 complex affects macrophage IL-6 production. These data suggest that loss of bacterial catalase results in prolonged ROS production following FcγR cross linking at the macrophage cell surface. By limiting H2O2 scavenging by the receptor-ligated bacterium, H2O2 likely permeates the cell membrane acting on redox-sensitive signals and driving macrophage IL-6 production.

FIGURE 8.

Treatment of macrophages with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin reduces production of IL-6. Enhanced production of IL-6 following WT BMDM stimulation with ΔkatGmAb immune complexes in the presence of 250 μm Apocynin. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 24 h poststimulation and IL-6 levels were analyzed by CBA. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference of p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that generation of ROS by the phagocyte NOX2 complex is required for macrophages to produce IL-6 following immune complex stimulation and cross-linking of the FcγR. This study also shows that macrophages lacking the catalytic subunit of NOX2, gp91phox, produce significantly lower levels of IL-6 following iFtmAb stimulation in vitro. This loss of IL-6 was directly tied to the inability of the macrophages to produce ROS upon stimulation with bacteria-containing immune complexes. Further, inhibition of ROS production via apocynin-mediated NOX2 inhibition or by direct scavenging by catalase decreased ROS and IL-6 production in wild-type macrophages in response to FcγR engagement.

In our investigations of the downstream signaling cascade of the FcγR following immune complex cross linking in gp91phox KO macrophages, a loss of ROS production led to a significant reduction in Akt phosphorylation as well as a significant decrease in IL-6 production. It is already known that the PI3K/Akt pathway serves as a key regulator of the NF-κB pathway upstream of IL-6 expression, and a reduction in the phosphorylation state of Akt correlates with the reduced kinase activity and subsequent IL-6 levels observed in primary macrophages upon LVS infection (43). We then expanded our studies to include the stimulation of both WT and gp91phox KO macrophages with catalase-deficient bacterial immune complexes, which showed decreased ability to scavenge NOX2-generated ROS during the early phase of FcγR engagement while eliciting significantly more IL-6 in primary murine and human macrophages.

The current interest of our group is to further our understanding of redox homeostasis in macrophages to maximize the ability of novel vaccine preparations to elicit innate immune responses which are the most beneficial toward inducing and improving the adaptive immune response. Here we establish that the production of IL-6, which contributes to the innate resistance of mice against many microbial pathogens, is controlled in a redox-dependent manner following stimulation of the FcγR by immune complexes. In this manner, we postulate that by targeting antigens to the FcγR, we are able to take advantage of redox-sensitive pathways to amplify cytokine production and vaccine efficacy. Thus, iFtmAb, which are unable to scavenge ROS are able to elicit higher levels of IL-6 compared with LVSmAb. It therefore stands to reason that vaccine formulations which themselves generate a physiologically relevant level of ROS would serve as effective adjuvants in future studies.

Direct comparison of FcγR signal transduction in WT versus gp91phox KO BMDMs yielded significant findings. Removal of gp91phox was accompanied by a reduction in the levels of phosphorylated Akt in the macrophages. This observation suggests that ROS enhances and propagates the activation signal following FcγR engagement which lies upstream of Akt. ROS have been implicated in the direct activation of Src family kinases, a key component of the FcγR signaling cascade (43). It is therefore feasible that continued ROS production maintains Src activity, resulting in a prolonged positive signal, resulting in increased PI3K activity, PIP3 accumulation, PDK1 recruitment, continued Akt phosphorylation, and NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. In addition, ROS may directly inactivate PTEN via oxidation, resulting in inhibition of its phosphatase function as a means of regulating cellular activation (44). PTEN acts in direct opposition to PI3K to regulate PIP3 levels within the cell (44, 45). Maintenance of active and non-oxidized PTEN is a hallmark of early infection with either type A or type B Francisella, and has been shown to directly inhibit the ability of macrophages to secrete IL-6 and TNFα (23). The inability of gp91phox KO macrophages to generate an effective IL-6 response following immune complex stimulation may also result in the direct oxidation and activation of NF-κB, bypassing other transduction pathways such as Akt, ERK, or c-Jun. Increased intracellular concentrations of H2O2 have been shown to prolong nuclear localization of NF-κB, by inhibiting negative regulators of NF-κB-controlled gene expression (46), as well as enhancing binding of NF-κB to promoter regions of DNA (46). Each of these proposed mechanisms have merit, but more investigation is needed to elucidate the specific redox sensitive target protein(s) within the FcγR signal transduction cascade responsible for our observed phenotype. While it is known that engagement of the FcγR directly leads to ROS production, ours is the first to show a direct link between NOX2-mediated ROS production and inflammatory cytokine production. The role ROS on propagating FcγR signal transduction cascade may be global, as multiple effector proteins have been described as redox sensitive, or be specific to one kinase or phosphatase involved. Further studies will need to elucidate the oxidative target responsible the difference in phenotypes described here.

Previous reports have shown that immunization with antioxidant-deficient bacteria induce a protective level of immunity against virulent Francisella challenge. Mice immunized intranasally with a single low dose of superoxide dismutatase B-deficient LVS (ΔsodB) induce significant protection against intranasal challenge with the more virulent type A Schu S4 strain (47). In this study, we show that IL-6 production by macrophages is greatly enhanced when another antioxidant deficient strain of LVS, ΔkatG, is targeted to the FcγR. Combined with the report by Rawool et al. that iFtmAb induces a similar level of protection against Schu S4 challenge as ΔsodB, these data support further resting of targeting antioxidant deficient bacteria to the FcγR, which may generate a stronger, more effective, or longer lasting immune response against virulent challenge.

In summary, we have presented data showing that NOX2-dependent ROS are required for the production of IL-6 following antigen targeting and cross linking of the FcγR. Removal of NOX2 directly interfered with production of IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine involved in successful control of primary bacterial infection as well as induction of the adaptive immune response against a wide range of pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Shekhar Bakshi for excellent scientific discussions over the course of this study. We thank Dr. Dennis Metzger and Sharon Salmon for the gift of gp91phox KO mice. Finally, we thank the animal research facility and CIMD immunology core for expert technical assistance during the course of these studies.

Footnotes

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- BMDM

- murine bone marrow-derived macrophage

- iFt

- inactivated Francisella tularensis

- NOX

- NADPH oxidase complex

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dröge W. (2002) Free Radicals in the Physiological Control of Cell Function. Physiological Rev. 82, 47–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeLeo F. R., Allen L.-A. H., Apicella M., Nauseef W. M. (1999) NADPH Oxidase Activation and Assembly During Phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 163, 6732–6740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fridovich I. (1978) The biology of oxygen radicals. Science 201, 875–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarfstein R., Gorzalczany Y., Mizrahi A., Berdichevsky Y., Molshanski-Mor S., Weinbaum C., Hirshberg M., Dagher M.-C., Pick E. (2004) Dual Role of Rac in the Assembly of NADPH Oxidase, Tethering to the Membrane and Activation of p67phox: A STUDY BASED ON MUTAGENESIS OF p67phox-Rac1 CHIMERAS. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16007–16016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bokoch G. M., Diebold B. A. (2002) Current molecular models for NADPH oxidase regulation by Rac GTPase. Blood 100, 2692–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nisimoto Y., Motalebi S., Han C.-H., Lambeth J. D. (1999) The p67 phox Activation Domain Regulates Electron Flow from NADPH to Flavin in Flavocytochromeb 558. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22999–23005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heyworth P. G., Bohl B. P., Bokoch G. M., Curnutte J. T. (1994) Rac translocates independently of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase components p47phox and p67phox. Evidence for its interaction with flavocytochrome b558. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30749–30752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryan T. C., Weil G. J., Newburger P. E., Haugland R., Simons E. R. (1990) Measurement of superoxide release in the phagovacuoles of immune complex-stimulated human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods 130, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson C. L., Guyre P. M., Whitin J. C., Ryan D. H., Looney R. J., Fanger M. W. (1986) Monoclonal antibodies to Fc receptors for IgG on human mononuclear phagocytes. Antibody characterization and induction of superoxide production in a monocyte cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 12856–12864 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Goes A., Brouwer J., Hoekstra K., Roos D., van den Berg T. K., Dijkstra C. D. (1998) Reactive oxygen species are required for the phagocytosis of myelin by macrophages. J. Neuroimmunol. 92, 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asehnoune K., Strassheim D., Mitra S., Kim J. Y., Abraham E. (2004) Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species in Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent Activation of NF-κB. J. Immunol. 172, 2522–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanlioglu S., Williams C. M., Samavati L., Butler N. S., Wang G., McCray P. B., Jr., Ritchie T. C., Hunninghake G. W., Zandi E., Engelhardt J. F. (2001) Lipopolysaccharide Induces Rac1-dependent Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Coordinates Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Secretion through IKK Regulation of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30188–30198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang C.-S., Shin D.-M., Lee H.-M., Son J. W., Lee S. J., Akira S., Gougerot-Pocidalo M.-A., El-Benna J., Ichijo H., Jo E.-K. (2008) ASK1-p38 MAPK-p47phox activation is essential for inflammatory responses during tuberculosis via TLR2-ROS signalling. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 741–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaka T. N., N, Kishimoto T. (2002) The paradigm of IL-6: from basic science to medicine. Arth. Res. Therap 4, S233-S242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gómez-Guerrero C., López-Armada M. J., González E., Egido J. (1994) Soluble IgA and IgG aggregates are catabolized by cultured rat mesangial cells and induce production of TNF-α and IL-6, and proliferation. J. Immunol. 153, 5247–5255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiener P. A., Rankin B. M., Burkhardt A. L., Schieven G. L., Gilliland L. K., Rowley R. B., Bolen J. B., Ledbetter J. A. (1993) Cross-linking of Fcγ receptor I (FcγRI) and receptor II (FcγRII) on monocytic cells activates a signal transduction pathway common to both Fc receptors that involves the stimulation of p72 Syk protein tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 24442–24448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lietzke S. E., Bose S., Cronin T., Klarlund J., Chawla A., Czech M. P., Lambright D. G. (2000) Structural basis of 3-phosphoinositide recognition by pleckstrin homology domains. Mol. Cell 6, 385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim S., Clément M.-V. (2007) Phosphorylation of the survival kinase Akt by superoxide is dependent on an ascorbate-reversible oxidation of PTEN. Free Radical Biol. Med. 42, 1178–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karin M. (2002) NF-[kappa]B at the crossroads of life and death. Nature Immunol. 3, 221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Libermann T. A., Baltimore D. (1990) Activation of interleukin-6 gene expression through the NF-κB transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2327–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reynaert N. L., van der Vliet A., Guala A. S., McGovern T., Hristova M., Pantano C., Heintz N. H., Heim J., Ho Y.-S., Matthews D. E., Wouters E. F. M., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. W. (2006) Dynamic redox control of NF-κB through glutaredoxin-regulated S-glutathionylation of inhibitory κB kinase β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 13086–13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Oliveira-Marques V., Cyrne L., Marinho H. S., Antunes F. (2007) A Quantitative Study of NF-κB Activation by H2O2: Relevance in Inflammation and Synergy with TNF-α. J. Immunol. 178, 3893–3902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melillo A. A., Bakshi C. S., Melendez J. A. (2010) Francisella tularensis Antioxidants Harness Reactive Oxygen Species to Restrict Macrophage Signaling and Cytokine Production. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27553–27560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoge J., Yan I., Jänner N., Schumacher V., Chalaris A., Steinmetz O. M., Engel D. R., Scheller J., Rose-John S., Mittrücker H.-W. (2013) IL-6 Controls the Innate Immune Response against Listeria monocytogenes via Classical IL-6 Signaling. J. Immunol. 190, 703–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romani L., Mencacci A., Cenci E., Spaccapelo R., Toniatti C., Puccetti P., Bistoni F., Poli V. (1996) Impaired neutrophil response and CD4+ T helper cell 1 development in interleukin 6-deficient mice infected with Candida albicans. J. Exp. Med. 183, 1345–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okada M., Kita Y., Kanamaru N., Hashimoto S., Uchiyama Y., Mihara M., Inoue Y., Ohsugi Y., Kishimoto T., Sakatani M. (2011) Anti-IL-6 Receptor Antibody Causes Less Promotion of Tuberculosis Infection than Anti-TNF-α; Antibody in Mice. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ladel C. H., Blum C., Dreher A., Reifenberg K., Kopf M., Kaufmann S. H. (1997) Lethal tuberculosis in interleukin-6-deficient mutant mice. Infection Immunity 65, 4843–4849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dube P. H., Handley S. A., Lewis J., Miller V. L. (2004) Protective Role of Interleukin-6 during Yersinia enterocolitica Infection Is Mediated through the Modulation of Inflammatory Cytokines. Infection Immunity 72, 3561–3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurtz S. L., Foreman O., Bosio C. M., Anver M. R., Elkins K. L. (2013) Interleukin-6 Is Essential for Primary Resistance to Francisella tularensis Live Vaccine Strain Infection. Infection Immunity 81, 585–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeda K., Mehta H., Drevets D. A., Coggeshall K. M. (2010) IL-6 increases B-cell IgG production in a feed-forward proinflammatory mechanism to skew hematopoiesis and elevate myeloid production. Blood 115, 4699–4706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rawool D. B., Bitsaktsis C., Li Y., Gosselin D. R., Lin Y., Kurkure N. V., Metzger D. W., Gosselin E. J. (2008) Utilization of Fc Receptors as a Mucosal Vaccine Strategy against an Intracellular Bacterium, Francisella tularensis. J. Immunol. 180, 5548–5557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilson J. E., Katkere B., Drake J. R. (2009) Francisella tularensis Induces Ubiquitin-Dependent Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Degradation in Activated Macrophages. Infection Immunity 77, 4953–4965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loegering D., Lennartz M. (2004) Signaling Pathways for Fcγ Receptor-Stimulated Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Secretion and Respiratory Burst in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Inflammation 28, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tian W., Li X. J., Stull N. D., Ming W., Suh C.-I., Bissonnette S. A., Yaffe M. B., Grinstein S., Atkinson S. J., Dinauer M. C. (2008) FcγR-stimulated activation of the NADPH oxidase: phosphoinositide-binding protein p40phox regulates NADPH oxidase activity after enzyme assembly on the phagosome. Blood 112, 3867–3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van den Dobbelsteen M. E., van der Woude F. J., Schroeijers W. E., van Es L. A., Daha M., R,. (1993) Soluble aggregates of IgG and immune complexes enhance IL-6 production by renal mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 43, 544–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones S. A. (2005) Directing Transition from Innate to Acquired Immunity: Defining a Role for IL-6. J. Immunol. 175, 3463–3468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kishimoto T. (2006) Interleukin-6: discovery of a pleiotropic cytokine. Arth. Res. Therap. 8, S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huntress E., Stanley L., Parker A. (1934) The Preparation of 3-Aminophthalhydrazide for Use in the Demonstration of Chemiluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 56, 241–242 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lundqvist H., Kricka L. J., Stott R. A., Thorpe G. H. G., Dahlgren C. (1995) Influence of different luminols on the characteristics of the chemiluminescence reaction in human neutrophils. J. Bioluminescence Chemiluminescence 10, 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Häcker H., Karin M. (2006) Regulation and Function of IKK and IKK-Related Kinases. Sci. STKE 2006, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCord J. M., Keele B. B., Fridovich I. (1971) An Enzyme-Based Theory of Obligate Anaerobiosis: The Physiological Function of Superoxide Dismutase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 68, 1024–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Melillo A. A., Mahawar M., Sellati T. J., Malik M., Metzger D. W., Melendez J. A., Bakshi C. S. (2009) Identification of Francisella tularensis Live Vaccine Strain CuZn Superoxide Dismutase as Critical for Resistance to Extracellularly Generated Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6447–6456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rajaram M. V. S., Ganesan L. P., Parsa K. V. L., Butchar J. P., Gunn J. S., Tridandapani S. (2006) Akt/Protein Kinase B Modulates Macrophage Inflammatory Response to Francisella Infection and Confers a Survival Advantage in Mice. J. Immunol. 177, 6317–6324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee S.-R., Yang K.-S., Kwon J., Lee C., Jeong W., Rhee S. G. (2002) Reversible Inactivation of the Tumor Suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20336–20342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leslie N. R., Bennett D., Lindsay Y. E., Stewart H., Gray A., Downes C. P. (2003) Redox regulation of PI 3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN. EMBO J. 22, 5501–5510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Enesa K., Ito K., Luong L. A., Thorbjornsen I., Phua C., To Y., Dean J., Haskard D. O., Boyle J., Adcock I., Evans P. C. (2008) Hydrogen Peroxide Prolongs Nuclear Localization of NF-κB in Activated Cells by Suppressing Negative Regulatory Mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18582–18590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bakshi C. S., Malik M., Mahawar M., Kirimanjeswara G. S., Hazlett K. R. O., Palmer L. E., Furie M. B., Singh R., Melendez J. A., Sellati T. J., Metzger D. W. (2008) An improved vaccine for prevention of respiratory tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis SchuS4 strain. Vaccine 26, 5276–5288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]