Abstract

In the United States, Blacks are disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS. Sexual networks and concurrent relationships have emerged as important contributors to the heterosexual transmission of HIV. To date, Africa is the only continent where an understanding of the impact of sexual concurrency has been conveyed in HIV prevention messaging. This project was developed by researchers and members of the Seattle, WA African American and African-Born communities, using the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Interest in developing concurrency messaging came from the community and resulted in the successful submission of a community-academic partnership proposal to develop and disseminate HIV prevention messaging around concurrency. We describe: (a) the development of concurrency messaging through the integration of collected formative data and findings from the scientific literature; (b) the process of disseminating the message in the local Black community; and (c) important factors to consider in the development of similar campaigns.

Keywords: HIV, Blacks, concurrency, CBPR, sexual networks, STI transmission

Introduction

In King County, Washington, as is the case throughout the United States, African Americans and African-Born (Black) members of the community are disproportionately affected by HIV (Morris, Kurth, Hamilton, Moody, & Wakefield, 2009). The Black community comprises only 6% of the King County population, yet they represent 17% of those presumed living with HIV or AIDS (Public Health Seattle and King County (PHSKC), 2010a). Black individuals living in King County are 2.7 times more likely than Whites to be living with HIV. The epidemic in King County disproportionately impacts African American men who have sex with men (MSM) and African-Born heterosexually-identified individuals, with Kenyans and Ethiopians having the highest infection rates (PHSKC, 2010b).

Historically, individual-level behaviors have been the focus of HIV prevention and intervention efforts. However, over the last decade population-level parameters of sexual behavior have emerged as important determinants of HIV transmission (Aral, 1999). Although not without its critics (Lurie & Rosenthal, 2010a, 2010b, 2009; Sawers & Stillwaggon, 2010), concurrent sexual partnerships, or sexual relationships that overlap in time (Morris & Kretzchmar, 1997), have emerged as potential independent risk factors contributing to the heterosexual transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among African Americans (Morris et al., 2009; Adimora, Schoenbach, & Doherty, 2006; Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005). When a person engaging in sexual concurrency becomes infected, that person has the potential to immediately transmit that infection to all of his or her other current partners. Unlike serial monogamy, the protective effect of sequential partnerships is lost in sexual concurrency because an individual is not required to end one relationship before they begin another. This means current partner(s) receive no more protection than partners acquired later. (Morris & Kretzchmar, 1997).

Concurrent relationships also permit faster dissemination of HIV and other STIs through partnership networks because there is no delay in the transmission of disease (Morris & Kretzchmar, 1997). It has been shown through mathematical modeling that as the prevalence of concurrency increases in a population, both the rate of epidemic growth in its initial phase and the average number of individuals infected after a given time increase (Kretzschmar & Morris, 1996). In addition, because concurrency leads to a rapid linkage of persons into a connected sexual network, even a very small increase in the average number of concurrent sexual partners can dramatically increase the risk of HIV transmission in a sexual network (Morris, Goodreau, & Moody, 2007). Conversely, it may take only a relatively small reduction in the average number of concurrent sexual partners in a community to have a dramatic impact on reducing HIV transmission. Concurrency particularly enhances population spread of HIV because of the virus’s long duration of infectiousness (Garnett & Johnson, 1997), and it increases the opportunities for transmission during acute HIV infection when the transmission probability is greatest (Pinkerton, 2008; Pilcher et al., 2004). Although acute infection is time limited, there is some evidence that a subset of HIV-1 subtype C-infected individuals maintains high plasma HIV-1 levels for an extended period of time (Novitsky et al., 2011). The estimates from several mathematical modeling studies suggest that from 9-50% of HIV transmissions in a sub-Saharan African setting were attributable to sexual contact with individuals with early infection (Powers et al., 2011; Abu-Raddad & Longini, 2008; Hollingsworth, Anderson, & Fraser, 2008; Hayes & White, 2006; & Cohen & Pilcher, 2005). Two recent studies in Zimbabwe suggest that without concurrency to amplify transmission during the acute phase, the epidemic cannot be sustained (Eaton, Hallet, & Garnett, 2011; Goodreau, Cassels, Kasprzyk, Montano, Greek, & Morris, 2010) thus concurrency reduction could potentially end the epidemic in Zimbabwe.

Several social and structural forces drive the formation of concurrent sexual partnerships in the Black community. In formative research conducted with African American men and women in eastern North Carolina (Adimora et al., 2006), respondents reported multiple challenges including limited educational and employment opportunities, overwhelming economic injustice and racial discrimination, and barriers in obtaining job placement and advancement. These social and structural forces affect family and marriage dynamics and sex ratios, and have been documented extensively in studies of concurrency. Concurrency has been found to be strongly associated with being unmarried (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Doherty, 2007; Adimora, Schoenbach, Bonas, Martinson, Donaldson, & Stancil, 2002; Manhart, Aral, Holmes, & Foxman, 2002) and a history of incarceration (Adimora et al., 2007; Adimora, Schoenbach, Martinson, Donaldson, Stancil, & Fullilove, 2004; Adimora, Schoenbach, Martinson, Donaldson, Stancil, & Fullilove, 2003; Johnson & Raphael, 2006; Manhart et al, 2002). These factors are of particular importance in the Black community within the United States because marriage rates have continued to decline since the 1970s (Wilcox & Marquardt, 2010) and Black Americans continue to be disproportionately over-represented in the criminal justice system (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009).

Addressing sexual concurrency domestically within the Black community is imperative for a number of reasons. First, like most racial and ethnic groups in the United States, Black individuals tend to choose sexual partners within their own racial group (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). There is some evidence that this practice, known as assortative mixing, may be more common among African Americans than other ethnic and racial groups (Laumann & Youm, 1999). Second, existing disparities in HIV/AIDS in the Black community have resulted in an increased disease burden and community viral load in many Black communities domestically (Castel, Befus, Griffin, West, Hader & Greenberg, 2012; Das, Chu, Santos, Scheer, Vittinghoff, McFarland, & Colfax, 2010). Third, although Black individuals do not engage in sexual or substance-using behaviors that are any riskier than their White counterparts (Halfors, Iritani, Miller, & Bauer, 2007; Millet, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2003), within the Black community there exists a high prevalence of partnerships between people of differential infection risk (dissortative mixing). African Americans with only one partner in the past year have been found to be five times as likely as Whites to choose sexual partners with four or more partners in the past year (Laumann & Youm, 1999). This combination of assortative mixing, increased community disease burden and viral load, and dissortative risk mixing creates a situation within the Black community wherein there is high prevalence of HIV and tightly connected sexual networks that include individuals of differential risk.

Although there is a great deal of evidence to suggest high rates of concurrency in the Black community (Morris et al., 2009; Adimora, et al., 2007; Adimora, et al., 2004; Adimora et al., 2003; Adimora et al., 2002; Johnson & Raphael, 2006; Manhart et al., 2002) there are currently no domestic HIV prevention interventions designed to educate the Black community about concurrency and its impact on the spread of HIV/AIDS. The goal of this community initiated project was to design a concurrency messaging campaign using a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach to inform the Black community in King County, Washington about the higher HIV risk associated with concurrent sexual partnerships.

Ugandan Concurrency Messaging

The development and dissemination of an effective, culturally-sensitive concurrency message for the Black community in King County is based on accumulated scientific research and findings on concurrency and sexual networks (Shelton, 2010; Mah & Halperin, 2010; Eaton et al., 2011; Helleringer, Kohler, & Kalilani-Phiri, 2009; Morris et al., 2009; Morris & Kretzchmar, 1997). In addition, our efforts were modeled on a successful HIV prevention message campaign first developed in Uganda, entitled “zero-grazing”, encouraging people not to engage in multiple and concurrent partnerships. In 1986, the Ugandan government launched an innovative HIV prevention campaign that mobilized every level of society from prominent political figures to grass-roots organizers (Green et al., 2006). The “zero-grazing” campaign utilized a mass media approach and relied heavily on “community-based and face-to-face communication”, employing culturally-relevant interventions to encourage behavior change and collaborating with important faith-based community leaders, women’s organizations, and ordinary people (Epstein, 2004; Green et al., 2006).

By 2003, rates of HIV in Uganda had dropped to about 4% or 5% from a peak of 15% in the early 1990s (Green et al., 2006; Shelton, Halperin, Nantulya, Potts, Gayle, & Holmes, 2004). During the same period, the proportion of men reporting three or more non-regular partners decreased from 15% in 1989 to 3% by 1995 (Shelton et al., 2004). While critics have argued that the decline in HIV prevalence was due to an increase in condom use and AIDS-related mortality (Lurie & Rosenthal, 2010a; Sawers & Stillwagon, 2010), modeling studies find that mortality only explains about 10% of the total decline in Uganda (Hallett et al., 2006), and there is compelling evidence to suggest that “being faithful,” (i.e., having one sex partner at a time) or reducing rates of sexual concurrency, was likely an important factor in Uganda’s success (Green et al., 2006; Stoneburner & Low-Beer, 2004; Shelton et al., 2004; Wilson, 2004). Reductions in multiple concurrent partnerships by men unable to afford maintaining several households has been posited to account for Zimbabwe’s similarly dramatic decline in HIV prevalence during the economic upheaval in that country (Halperin et al., 2011). Mass media campaigns in the spirit of “zero grazing” are also rolling out in many countries of sub-Saharan Africa under the “One Love” initiative, after the South African Development Community (SADC) targeted concurrent partnerships as a priority for 2006 (SADC, 2006)

Our efforts to develop and disseminate concurrency messages in the Black community in Seattle are based on the significant HIV prevention success experienced by African countries when utilizing a community-based approach to address concurrency and its potential impact on HIV infection rates.

Methods

Phase One

In 2007, the University of Washington (UW) Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Community Action Board (CAB) co-sponsored a seminar on “Disparities in HIV-STIs: Impacts on African-American and African-Born Populations” with the UW CFAR Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core (SPRC). This full-day seminar was attended by over 150 researchers, students, service providers, and community members. The interest in new approaches to thinking about racial disparities and HIV generated by the seminar led to the creation of a new CAB working group on HIV Disparities. The Disparities working group (DWG) was comprised of over 40 participants from the local community, representatives from over 15 community-based organizations and HIV service providers, as well as UW researchers and staff. DWG members identified concurrency and the lack of knowledge about its connection to HIV transmission as a pressing issue for the local Black community. Utilizing community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998) to ensure equitable partnerships, the DWG, community members and researchers successfully submitted an R21 proposal to translate the scientific findings on sexual networks and concurrency into culturally resonant prevention messages to reduce racial disparities in HIV among Black populations in Seattle/King County. Throughout the project, quarterly informational and feedback sessions were held for all DWG members to ensure cooperative participation from community and research partners in a forum wherein both contributed equally (See Table One for delegation of duties). These sessions consisted of progress reports and discussion of next steps and actions. Additionally, biannual training sessions were held to increase local community research capacity and researcher cultural responsiveness.

Table 1.

Community/Academic Partner Responsibilities

| COMMUNITY PARTNERS | ACADEMIC PARTNERS |

|---|---|

| Identify interviewers, project coordinators, and focus group facilitators | Grant Management |

| Continued input and feedback on advertising concepts | Compilation of reports and updates on feedback for advertising concepts |

| Dissemination of announcements and updates | Dissemination of announcements, reports and updates |

| Marketing proposal review and selection | Marketing Firm RFP management |

| Focus group recruitment and hosting | Staff Supervision |

| Identifying locations for grassroots advertisement dissemination | IRB |

Phase One: Key Informant Interviews

During the first phase of the project (year one) formative data were collected to inform message development. Human Subjects approval was obtained at the UW (HSD #34436). We utilized a phenomenological approach (Moustakas, C., 1994; van Manen, M, 1990) to explore the Black community’s experience of concurrent relationships, their impact on the community, and effective messaging strategies. DWG members identified ten leaders/stakeholders in the African American community and nine (4 Kenyan, 3 Ethiopian, 1 Somalian, and 1 Tanzanian) leaders/stakeholders in the African-Born community. These stakeholders were asked to participate in key informant interviews, lasting 60 to 90 minutes. Key informants (n = 19) were provided $20 for their time. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and all identifying information was removed from the final transcript. After the informed consent process, key informants reviewed an educational worksheet (created by a community member with graphic design experience) that provided HIV epidemiology data for the local Black community, information on concurrency and its connection to HIV transmission, and an overview of the “zero-grazing” campaign in Uganda. Interview topics included: perceptions and beliefs about HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS prevention, sexual networks and concurrency, message framing and development, message dissemination, and community norms/beliefs regarding concurrency and HIV. Results from key informant interviews were presented to the DWG. Community and research partners utilized this data to develop the focus group topic guide and determine focus group composition.

Selecting a Marketing Partner

At the end of phase one a marketing working group (MWG) was formed from the larger DWG. The MWG was tasked with selecting a marketing firm to assist in the creation of the concurrency messaging. MWG members researched local and national marketing firms with experience working with Black communities to develop HIV/AIDS prevention messaging. The group created a request for proposals and distributed the document to eleven marketing firms. Three applications were received, reviewed, and scored by group members. Following selection, two firm staff members became involved as members of the DWG providing expertise, advice, and direction.

Phase Two: Focus Groups

During phase two, eleven focus groups (N=80) were conducted. DWG members used the key informant data to assist in determining the composition and quantity of focus groups. A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit participants based on the HIV/AIDS epidemiological data available for the local Black community. Because African American MSM and African-Born heterosexually-identified individuals, particularly Kenyans and Ethiopians, have the highest infection rates in the Seattle/King County area, these communities were the focus of recruitment efforts. We conducted 3 mixed African American and African-Born adult women groups; 2 MSM groups; 2 adult African-Born men groups; 3 mixed African American and African-Born youth (ages 18-24) groups; and 1 African American adult men group. All focus groups were held at community locations to ensure convenience for participants. African American and African-Born community members were hired and trained to facilitate focus groups and conduct qualitative data analysis. Facilitators for each group were matched to focus group participants by age, race, gender, sexual orientation and country of origin. Focus groups were 90 to 120 minutes in length. Each was audio recorded and transcribed, and all identifying information was removed from the final transcript. Each focus group participant received $30. After providing verbal informed consent, each participant reviewed the educational worksheet (described above). Focus group topics for discussion included: perceptions of concurrency; beliefs about concurrency; perceptions of HIV/STI risk as they relate to concurrent behaviors; and concurrency messages.

Phase Three: Message Development and Dissemination

Concurrency messages were developed based on data collected in the earlier project phases, refined, and approved for release to the public by the DWG. Based on key-informant and focus group findings, palm cards and fliers were created to disseminate the concurrency message. Messages were initially distributed through a targeted grassroots campaign wherein project staff saturated the Black community with concurrency palm cards and fliers. The recruitment team (comprised of research staff and trained community members) identified areas by zip code with large numbers of African-Born and African American residents. These areas were visited weekly by a team of three to five recruiters. Additionally, throughout the grass roots campaign we utilized an educational worksheet (described above), designed by an African American community member, which included local HIV/AIDS epidemiological data and an illustration of concurrency and its relationship to the spread of HIV, as a tool to educate and make HIV more “real” for community members. During these encounters with Black community members, project staff discussed disparities in HIV prevalence and incidence as well as the connection between concurrency and HIV transmission. African-Born and African American business owners were approached, educated about HIV and concurrency, and asked to post flyers in their establishments. Several weeks into the grassroots campaign, community members began to request community workshops on concurrency. Project staff were trained to facilitate concurrency workshops and group discussions utilizing a slide set created to improve community knowledge and awareness of concurrency, and began facilitating workshops throughout the community. Approximately two months after the launch of the grassroots campaign, the ads were placed in African American and African-Born newspapers, and project staff presented concurrency and HIV information on African-Born public access television and African American radio programs.

A website (www.stopconcurrency.org) was created by research staff as a tool to support the educational efforts of the concurrency messaging campaign. Website content included a description of the campaign, data on sexual partner concurrency and its impact on sexual networks and HIV transmission, Seattle/King County HIV and concurrency statistics, and linkages to HIV testing and care. The website URL was included on all campaign materials, and participants approached during street and business intercepts were directed to the website for further information. The website was maintained for the duration of the concurrency messaging campaign (3 months).

Phase Four: Message Evaluation

Evaluation of the messages’ reception in the community was done using a one-time recall test administered on a personal digital assistant (PDA) to a random sample of African American and African-Born individuals during street intercepts approximately 3 months after the launch of the HIV prevention campaign. To assess the HIV prevention messages, evaluation questions measured quantified outcomes, included fill-in-the-black responses, and assessed message comprehension and recall, perceived impact of messaging, and perceived impact on attitude strength. Evaluation methods and results will be forthcoming.

Data Analysis

Interview and focus group data were analyzed utilizing thematic data analysis steps (Moustakas, 1994; Polkinghorne, 1989). A group of five staff members, two of whom were community members, individually coded the first two interviews (and later focus groups). Team members then met to discuss the meaning of significant statements, identifying areas of agreement and discrepancy. Each discrepancy was discussed until a consensus from all team members was reached as to the meaning of the significant statement. Next, team members developed themes which were used to construct an initial codebook. The code book was used as a guide to code subsequent interviews. The team worked to identify new themes as well as refine existing themes and categories. Final themes and specific quotes from the data were given to the marketing partners to prepare the first round of advertisements for DWG review.

The final step of data analysis consisted of reviewing all the codes and the transcripts to identify umbrella themes that were endorsed by all community members and population specific themes (i.e., those only endorsed by MSM, African-Born men, youth, etc.). The data analysis team met weekly and held in-depth discussions of each theme and how it arose across and within groups. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was met.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 99 African American and African-Born community members participated in the key informant interviews (n=19) and focus groups (n=80). Key informants were comprised of ten African American and nine African-Born individuals. African American key informants included six adults (ages 25 and older) and four youth (ages 18 – 24), four males and six females, and 3 gay-identified individuals (2 male and 1 female). Five of the African American key informants were HIV/AIDS service providers and five were community members. African-Born key informants included six adults and three youth, six females and three males and represented four African countries (4 Kenyan, 3 Ethiopian, 1 Somalian, and 1 Tanzanian). Four of the African-Born key informants were HIV/AIDS service providers and five were community members.

A total of 80 African-Born and African American community members participated in the eleven focus groups: two (2) African Born heterosexual adult male groups (n=12); one (1) African American heterosexual adult male group (n=7); two (2) Black adult men who have sex with men (MSM) groups (n=17); three (3) adult mixed African American and African-Born adult heterosexual female groups (n=25, 12 US born and 13 African Born); and three (3) mixed African American and African-Born male and female youth groups (n=19). Mean age of participants was 33 with a range of 18 to 67. Forty five respondents reported being born in the United States and 35 reported being born in an African country.

Data analysis revealed five themes that were utilized to guide the development of a concurrency message for the Black community: concurrency as normative; lack of constructive discussion about sex; the perception that HIV is not real enough; the need to include a message about protection; and the lack of a single word or metaphor to replace “concurrency” (See Table Two). Except where noted, responses were essentially unanimous concerning data themes outlined below and did not vary substantially by gender, age group, sexual orientation, or birth country.

Concurrency as Normative

All respondents identified concurrency as a normative behavior in the local Black community and offered many examples of concurrent behaviors. Most respondents felt that relationships where concurrency did not exist were rare. “You know, every time you ask who does concurrency, I giggle because I think it’s easier to answer, if we asked, who doesn’t,” said an African-Born man.

The majority of both male and female African-Born respondents perceived concurrency as a part of their culture or tradition. Concurrent behaviors among African-Born men living in the United States were often linked to the practice of polygamy in African countries. “Culturally, my grandpa had five wives and it was not a secret because that’s a traditional thing. I think the new generation was taught to be monogamous Christians. Otherwise, they’re still trying to be like grandpa. They’re just hiding it,” stated one African-Born woman.

Among youth, respondents reported viewing concurrency as normative and acceptable behavior. “It’s socially acceptable nowadays,” said an African American youth. Both male and female participants perceived concurrency as an expected behavior, especially for men. Several female respondents reported feeling the need to expect this behavior from men and to not assume that the relationship is monogamous when dating. Many female participants stated that they would be shocked or surprised if they encountered a man who was not engaging in concurrent behaviors. “I think it’s so common among Black men in my age group that I would be shocked when I find that it’s not taking place,” said an African American adult woman. Although all participants viewed concurrent behaviors to be more common among Black men, several believed concurrent sexual partnerships to be common among Black women as well, particularly African American women.

MSM respondents also perceived the normative nature of concurrency in the local gay community as leading to expectations of concurrent behavior among MSM. “I think it’s an expectation that people do it - that people are doing it. Not that it’s a favorable thing, but that people are doing it. It’s how it is - it’s kind of an accepted norm,” stated one African American MSM. Concurrency was described as being so normalized in the MSM community that if you were not engaging in it you were in the minority. “So the fact that they are having multiple [and concurrent] partners is almost so normalized, that it’s not like, taboo. And in some cases it’s almost like, if you’re not having multiple partners, then you’re the one missing out,” said an African American MSM. Several MSM reported beliefs that not engaging in concurrency might negatively impact one’s social network. As one African American MSM described, “In fact, you can be ostracized for frowning upon it yourself.”

Most respondents felt that the Black community was not alone in its normative practice of concurrency and perceived concurrent behaviors to be pervasive throughout the United States and across racial and ethnic groups. “I’ve been everywhere so pretty much everybody does it that is what I would say about it. I’ve been in a White neighborhood, I’ve been in Puerto Rican neighborhoods, I’ve been everywhere and they all do it,” said an African-Born youth.

It’s not OK to talk about sex

Although concurrency is perceived as being normative, respondents unanimously felt that it was not discussed in the Black community in a constructive way. Participants identified an overall lack of discussion about sexual topics in the community.

I think our collective cultures as people of African descent, we humans, we’re sexual beings but when it comes to talking about sex, I think whether you’re East African, West African; whether you’re West Indian, whether you’re African American, we’ve always fallen short of being able to talk about that. And so that causes some problems. You know, we can do the do, we can get down, but when it comes to talking about certain things we clam up. And so I think that fuels part of it.

– African American MSM

The stigma attached to discussion of sexual topics was perceived as a major barrier to open communication about any topics related to sex and sexuality. “And I don’t know what the stigma is in the Black community about openness. A lot of people would rather just pay a blind eye and let things be,” said an African-Born man. It was also attributed to fear of how one might be perceived or talked about by others. “I’m from Ethiopia, so talking about sex, it’s like a phobia, you know? You don’t really talk about it. We’re not really open. We’re not raised to talk about it openly like this,” said an African-Born woman. Some respondents felt that sexual topics such as concurrency are not discussed because individuals in the Black community did not want others outside of the community to have any ammunition for additional negative perceptions of the Black community. “It’s [HIV/AIDS] such a stark reality where we come from. People don’t like to bring it up because sometimes it seems like you’re trying to paint where I come from in a bad way, but it’s really a reality,” said an African-Born woman.

This lack of discussion of sexual topics was viewed as negatively impacting knowledge of the risk of HIV/AIDS in the Black community. There was a general sense that community members were aware of HIV/AIDS. “There is an awareness of AIDS, but people just, or just STDs, but people don’t talk about that,” said an African-Born man. However, due to the lack of discussion of sexual topics, including HIV and AIDS, participants believed that most Black individuals in Seattle and King County are not aware of the high rates locally and, as a result, do not perceive themselves to be at risk. “That’s why a lot of people don’t understand why HIV and this entire rate is so high because people are not talking about it,” said an African American woman.

Interestingly, while respondents perceived that concurrency was generally not discussed in the Black community, they acknowledged that when it was discussed it was done so in a negative and often unproductive manner. “If you’re sitting here, and you’re talking about concurrency, it’s in a bad way. And you’re talking about your friend or you’re talking behind somebody’s back or something like that. You never have the chance to come out and really speak about it until now, and that’s a shame,” said an African American man. The negative discussions around concurrency were perceived as creating additional barriers for open communication such as fear of judgement or being the subject of gossip.

I feel like a lot of people keep what they do low key because they’re scared of judgment or somebody’s reaction and too many people can’t be trusted. You don’t wanna be shot down about it, especially if you’re already feeling guilty about it. You don’t wanna get shot down. Like you’re so stupid, why would you do that? Nobody wants to hear that.

(Female youth)

These fears keep actual practices of concurrency out of public view and discussion. “People have a fear of gossip, so they have a tendency to keep the people that they’re dealing with below the radar and on the low. So there’s a high level or high chance that somebody’s messing with two people at the same time because as long as the secret’s quiet, nobody will find out,” explained an African-Born youth.

The perceived normative nature of concurrency and the associated fear or shame if discovered practicing concurrency was viewed as pushing concurrent behaviors further out of community discussions and promoting the need to hide these behaviors from others. This was even the case for men, who participants noted were often held in esteem for concurrent behavior. “A man who cheats on his wife or a woman who does the same thing is looked down on in the [African] community. It’s a really, really bad thing and that’s why people hide and go behind closed doors and they don’t talk about it is because of that I think,” said an African-Born woman. Many male respondents discussed the need to take action to hide their concurrent behaviors. As one African-Born male stated, “My little sister covers for me. It seems like it’s a natural thing.”

MSM participants were the only group that reported public discussions of sexual topics including concurrency. These conversations, however, were reported as taking place in the past with current discussions being characterized by gossip or name calling. MSM reported that several years ago community based organizations offered spaces for MSM to discuss these issues. Unfortunately these services are no longer available. MSM perceived these spaces as providing a venue for healthy and positive discussions of sexual topics. Several MSM participants believed that the loss of these spaces had resulted in current discussions that are largely gossip driven.

HIV not “real” in the Black community

The community’s lack of discussion of sexual topics includes discussion of HIV and AIDS, which may decrease awareness of its impact on the local Black community. According to heterosexually-identified youth and adult respondents, HIV and AIDS is something that is happening elsewhere and is not seen as a local reality. “I don’t think the way it’s [HIV/AIDS] being presented makes it real enough to people. I’m not saying I know the solution for that. But you always think, oh yeah, HIV and AIDS is out there, but you don’t think it’s right here in your backyard. You don’t think the person sitting next to you on the bus could have HIV,” reported an African American youth.

For many of the African-Born respondents, HIV/AIDS was perceived as a problem in Africa but not a problem they should be concerned with now that they are in the United States. Many reported that the lack of media attention to or information on this topic promotes the idea that HIV and AIDS are not local problems. As one African-Born male explained, “I know that the whole AIDS thing is something that I worried about back home. I didn’t worry much about it here. I’ll be honest with you.” An African-Born youth commented, “It seems like they don’t talk about HIV much anymore. It’s rare to see an ad about HIV. It took me a long time and people think in America they don’t have this problem anymore, HIV and when people are moving here it seems like they forget about using condoms because they think everybody is safe and stuff.”

Most of the participants, with the exception of MSM participants, were not aware of anyone in their community who was HIV-positive and the majority was unaware of the disproportionately high rates of HIV in the local Black community. After reviewing the educational sheet, participants expressed shock or disbelief at the local HIV epidemiological data for the Black community. A female youth commented, “I don’t know anybody that has HIV. I don’t know anybody. I’ve never known anybody in my life.” An African-Born male questioned the accuracy of data presented:

I mean, how do we know, what was the population that led to that? Most Africans I know here, I’m sorry, don’t have any AIDS, and they’re always very safe. I mean, maybe we need to question these numbers and how to reach-is it trying to represent what people think should be the numbers that should be, because of what they think Africans are like, always going out and sleeping around? I mean, what is the basis of this?

In contrast, MSM respondents perceived HIV and AIDS as being very real for their community, but felt that the sense of urgency that was once held by the community was no longer present. As one MSM explained, “People know about HIV, but not as much as they used to. It like, died down. Magic Johnson’s got HIV, had it for eight, nine, ten years. But it’s not big, you know what I mean?” Most of the MSM respondents felt that the availability and effectiveness of antiretroviral therapies (ART), while wonderful for the overall health of their community, has led to a reduction in the importance of HIV and AIDS. “I think a lot of people think they can get HIV now and they don’t have the consequences… I know that with me in the 80’s, when you said that you’re gonna die in six months. And now there’s a lot of people that’s like, ‘I can take these pills and still live for 20, 30 years,’” said an African American MSM.

This belief was also held by the larger Black community. As one African-Born woman explained,

People don’t really fear AIDS because people can live over 5 years, 10 years. People fear cancer more than AIDS. Not in Africa or anything, but in America you can live a good life with AIDS. You can receive the medication, the treatment, everything. It’s not the ’70s fear of AIDS, the fear that’s there. You know how AIDS is going to kill you but you can live 30 years with it. You can live 25 years with it. You can still have your sex and everything you know. The fear is not as much as it was before. That affects the community.

A few respondents reported beliefs that a cure was available but limited to those who could afford it (e.g., Magic Johnson) or that a cure would be available soon. As one African American woman reported, “I’m also hearing there’s close to being a cure for it in some other place. I think that kind of sends people the message that if I get it I can just take this and I’ll be okay.”

Message components

Protection

When asked what a concurrency message would look like for the Black community, many of the adult male respondents felt that any message would have to include a protection piece. Community partners supported the inclusion of a protection message from the start of the project as well. One African-Born male commented, “And I’m not sure what’s the best thing. Maybe it’s just telling people to wear condoms because from just this conversation, I realize everybody has a different choice, everybody makes different choices and lifestyles.” African American male participants felt that any message for their community “would probably have to target things around protection” and suggested including “use protection every time” as part of the message.

An African-Born male felt that both a protection and treatment message were warranted, “You should just tell the people. One, they have to wear protection. Second thing, if they’re infected they have to go for treatment.” A few of the MSM respondents stated that when they had discussed concurrency in their community it was always accompanied by a protection message. “In my community, when we talk about concurrency, we tell them you need to use a condom if you plan on sleeping with that person; that’s how we use it. Be careful!” said an African American MSM. MSM respondents perceived the stigma attached to HIV and homosexuality to be a major barrier to concurrency messaging for the larger Black community. Educating the community about HIV and reducing the stigma around HIV and homosexuality was seen as a top priority in messaging.

So how do we get them to get past that shame of it [homosexuality] so they can just celebrate their life. They can go to a whole other city, but they can’t celebrate their lives. That’s what we need to try to get across to people. That there’s nothing wrong with being gay, it’s just who you are.

(African American MSM)

Replacing “Concurrency”

Through our formative research, we hoped to find a word that might be universally recognized in the local Black community to replace the more scientific term “concurrency”. Our key informants and focus group participants informed us that there are no judgment-neutral or more colloquial words that might be utilized to replace concurrency. In fact, the majority of the words used by respondents to describe concurrent behaviors or individuals engaging in those behaviors were negative. According to participants, all words utilized to describe women (e.g., slut, whore, tramp) were negative and many of the words used to describe men (e.g., baller, player, hustler), were perceived as having both positive and negative meanings. General terms used to describe concurrent behavior (e.g., careless, adultery, tricking, cheating, the down low) were perceived as being negative and judgemental as well.

There were mixed opinions among DWG members concerning the use of the word ‘concurrency’ in the campaign. Some felt that a less scientific word was needed to increase understanding. Others felt strongly that the campaign should focus on educating the community and that this education should include introduction and explanation of the term “concurrency”.

Discussion

Developing a Concurrency Messaging Campaign

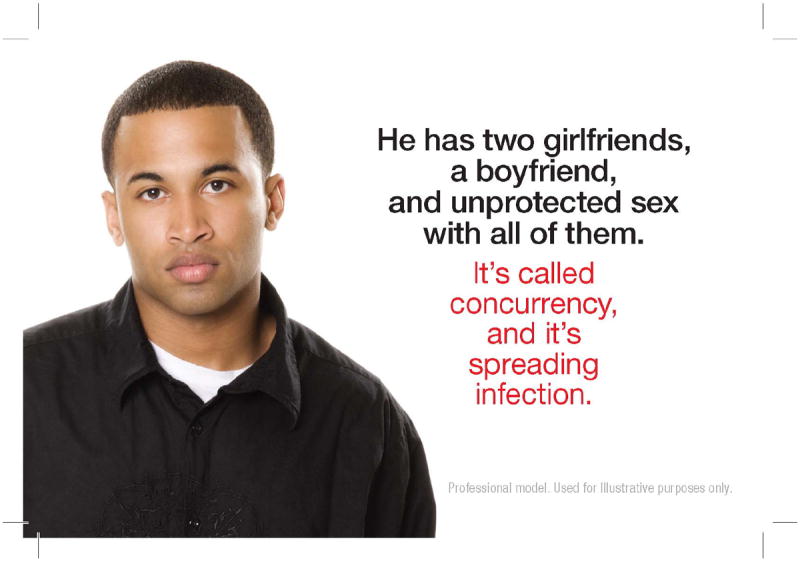

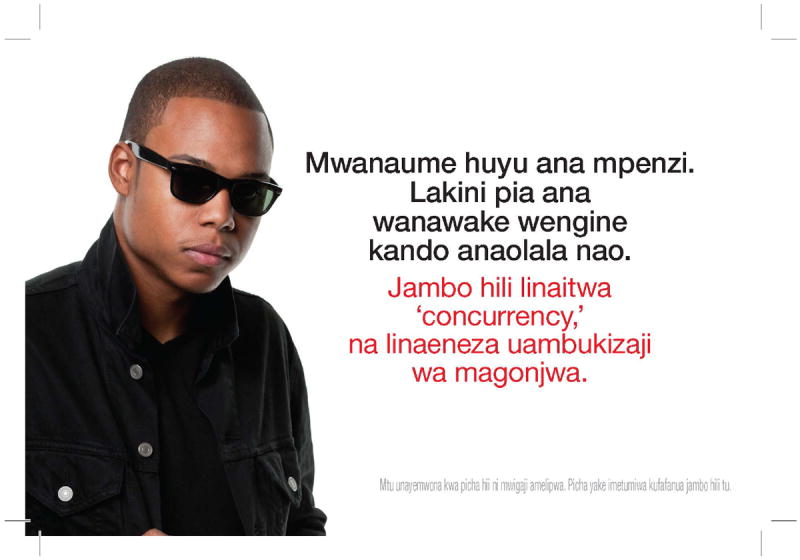

Drawing from the formative data, the DWG decided that a concurrency message for the Black community must achieve three aims: (1) provide HIV and concurrency education; (2) increase communication and discussion of HIV and concurrency; and (3) reduce stigma associated with discussing concurrency in the community. It was determined that the best means to achieve these aims was through the development of print media and an educational website. Print media would allow for wide message dissemination and the inclusion of multiple images to represent the wide range of individuals comprising the local Black community with minimal cost, while a project website would provide important additional information on concurrency and HIV that could not be included on the print media. Print media was in the form of palm cards and flyers and included direct quotes or descriptions of concurrent acts (e.g., “He has two girlfriends and he has unprotected sex with both of them.”) taken from the formative data, coupled with the tagline, “It’s called concurrency and it’s spreading infection”. The project website URL was displayed prominently on the materials so that individuals could access more information should they choose to do so. The majority of the quotes and descriptions of concurrent behaviors included the phrase “unprotected sex” to achieve the goal of including a protection piece in the messages. The tagline, “It’s called concurrency and it’s spreading infection”, was incorporated to introduce and educate the community about the meaning of concurrency. Initially, the tagline read “It’s called concurrency and it’s killing us.” Many DWG members pushed for this message due to its perceived strength and ability to grab community members’ attention. Others viewed it as fear-based, negative and judgmental. After much discussion and a review of several relevant articles (Spieldenner & Castro, 2010; Noar, Palmgreen, Chabot, Dobransky & Zimmerman, 2009; & Romer et al., 2009), it was decided that the tagline needed to educate the community about the impact of concurrency on HIV transmission and avoid utilizing fear-based or judgmental components.

Increase communication and discussion of HIV and concurrency

A primary goal of the grassroots campaign was to model open discussion of concurrency, sexual behavior and HIV/AIDS. Project staff worked to normalize open discussion of these “sensitive” topics throughout the community by modeling this behavior and engaging community members in dialogue during face-to-face encounters and concurrency workshops. In addition, project staff organized and facilitated community meetings and community leader luncheons where community members could openly exchange ideas and experiences about these sensitive topics in an effort to normalize open communication. Finally, to ensure sustainability, interested community members were trained and used a toolkit (i.e., educational sheet, talking points and PowerPoint presentation) to organize and facilitate discussions in the community. These materials are available on the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research Socio-behavioral Prevention Research Core website (www.sprc.washington.edu/index.php).

Reduce stigma associated with HIV and concurrency in the Black community

We sought to normalize behaviors and reduce stigma by taking examples of concurrency directly from the formative data to describe concurrent behaviors in a nonjudgmental and familiar way. In addition, the research team worked with members of the DWG to choose African American and African-Born male and female images and languages (English, Amharic, Swahili, Somali, Tigrinya) that would increase the likelihood that messaging would be more personal and recognizable to community members. Furthermore, we were aware that publicly placed media have the potential to provide unintended messages for audiences outside of the Black community (Spieldenner & Castro, 2010), so our placement of media focused on African-Born and African American neighborhoods, establishments and organizations. Throughout our grassroots campaign, we directly approached Black community members in an effort to avoid perpetuating the community’s vulnerable condition through messages that might be perceived as identifying concurrency as a “Black problem.” By doing so, we felt we were able to collaboratively focus the message positively on informing and protecting the Black community and avoid potentially stigmatizing messages. We were not successful in limiting our MSM materials to the Black MSM community. Because of the small size of the Black MSM community and our inability to identify Black-focused MSM services, organizations and businesses, these materials were often disseminated in local gay establishments with a majority of White patrons, or published in newspapers catering to the local MSM community. A forthcoming paper will detail our challenges in effectively engaging the local Black MSM community.

Overcoming Challenges in Community-based Messaging

Since the launch of the grassroots campaign, we have received an overall positive response from the community. We recently finished the collection of evaluation data and a report is forthcoming. In general, community members have welcomed the opportunity to discuss sensitive topics and to learn more about concurrency and HIV/AIDS. In some cases, individuals expressed feeling targeted by the campaign ads due to the fact that the images on the ads depicted only African American and African-Born Black men and women rather than individuals of other races and ethnicities. As a result, some reacted with anger due to the perception that the ads perpetuated stigma in the Black community. Research staff responded by describing the development of the campaign and its inclusion of Black community members, and the purpose of the campaign, which often resulted in community members asking for more information and praising the research project. In addition, some business owners were initially reluctant to post the fliers, expressing concerns about customer reactions. After engaging business owners in a discussion, the large majority agreed to post fliers. However, when returning to establishments several weeks later, many of the fliers were no longer posted. Staff documented these occurrences and follow up discussions with owners. These data are forthcoming and will be utilized to inform future efforts.

Throughout the development and implementation of the campaign we faced several challenges and have gained a wealth of knowledge that will inform future efforts. As discussed in the introduction, quarterly feedback sessions were held to ensure participation, input and feedback from community and academic partners throughout the project. These sessions were well attended and lively discussion, debate, and decision-making occurred at each. In the second year of campaign development, a community partner expressed concern that the voice of their organization was not being heard in these sessions. This prompted the principal investigator to reach out to all partners to ensure all opinions were considered in the creation of the campaign, offering one-on-one meeting opportunities for individual feedback. Meetings were scheduled with all interested parties. At each stage of the campaign, community needs and opinions were included in decision-making. This process required much time, flexibility and coordination by project staff.

Involving mass transit (and other potential media outlets) and public health representatives as well as elected officials early in the development of the campaign might have assisted in preventing project delays. Prior to the launch of the campaign, local mass transit officials had revised their guidelines for posting materials on buses and trains in response to an unrelated incident in which there was public outcry related to materials posted on public buses and subsequently rejected the campaign ads. As a result, original messaging which included first person wording and the phase “it’s killing us) (e.g., “I have two girlfriends. I have unprotected sex with them both.” It’s called concurrency and it’s killing us) that were considered unacceptable by mass transit officials, were changed to third person wording and the phrase “it’s killing us” was replaced with “its spreading infection. The first person wording was considered to be less effective by the DWG. Unfortunately, as a result of the rejection, the campaign experienced a six month delay in launching the mass transit advertisements and the research team was unable to pilot test the new messages. The delay caused by the rejection of advertising prompted the DWG to reconsider the advantages and disadvantages of advertising on mass transit. Providing information and increasing awareness for community members regarding the potential stigma associated with public health campaigns targeting the Black community early in the decision making process may have made the shift in focus from a mass transit campaign to a grassroots campaign smoother.

Over the course of the project there was a significant amount of community member turnover. Although the project team worked diligently to recruit and retain community members, challenges to retention (unstable employment, family emergencies, and competing demands such as childcare) persisted. Identifying back-up representatives and providing leadership roles coupled with monetary incentives (in addition to food at meetings) for participation might have helped increase consistent community member involvement.

We experienced several challenges in meeting the frequently divergent needs of community members, our academic institution, and marketing firm representatives. The biggest challenge was aligning needs with regard to timelines and deliverables. Community and marketing feedback was required for submission of modifications in accordance to IRB meeting schedules. The marketing firm required community feedback in a timely manner in order to incorporate this feedback into subsequent versions of ads. Community partners had multiple demands on their time, and scheduling multiple meetings and feedback sessions that accommodated the majority of participants was challenging. Identifying hard deadlines that coincide with IRB meetings in the planning stages of the project and incorporating enough time to accommodate community partner schedules is imperative for moving CBPR projects forward in a timely manner.

Finally, although we had spent a year prior to the project fostering community relationships and building strong collaborations, there was still a great deal of work to be done to strengthen existing partnerships and develop new partnerships. As others (Burhansstipanov et al., 2003; Strickland, 2006) have argued, true CBPR requires more time and funding than is conventionally allotted to achieve the specific aims of non-CBPR research projects. We found that to ensure true community participation where community input and guidance is incorporated at each step of the project, we were required to engage in activities that often translated into several months of information and feedback gathering before next steps could be taken. Advocating with funding institutions for extended time to conduct CBPR is imperative for successful community-academic partnerships.

Throughout the campaign, the team strengthened existing community relationships and built new ones. The academic team has strong partnerships with the local Black community and is currently working on identifying and obtaining funding for future collaborative efforts. The concurrency campaign has been well received and much of this success is the result of the intense level of collaboration inherent in the CBPR method. The grassroots campaign included street outreach, appearances on local African public access television programming, interviews on African American radio, and advertisements in African American and African-Born newspapers, and newspapers catering to the local MSM community. In addition, several community workshops were held and a number of community members were trained to discuss concurrency in their community. This approach allowed project staff to focus on the relatively small local Black community (6% of total population) without disseminating potentially stigmatizing messages to the larger community.

Messages developed in this campaign may assist in generating conversation regarding concurrency and HIV in other Black communities within the United States. The methods described here can be transported to other communities to obtain information to inform local concurrency messaging. Preliminary data collected in Washington, DC (Clad et al., forthcoming) indicates that the messages resonate for the Black community members living in Wards 5, 7 & 8, providing some support for national use of the messages. Lessons learned from this collaborative effort will be of use to those considering how to address sexual concurrency as a potentially powerful HIV prevention message, especially in communities disproportionately affected by HIV infection.

Figure 1. English Language Message for African American Heterosexual & MSM Community.

Figure 2. Kiswahili Language Message for the KenyanCommunity.

Front Text: He has a girlfriend. But he also has a couple of women on the side. It’s called concurrency and it’s spreading infection.” “Professional model. Used for illustrative purposes only.”

back Text: “Stop HIV/AIDS”.

Table 2.

Concurrency as Normative theme and related text

| THEMES | QUOTES |

|---|---|

| Concurrency as normative | African Men - According to everything else that I see, the books that I read, like the Bible, that’s what happened before me, I was here, they had 48 wives… |

| African Men - Well, amongst the Zimbabwean community that I have experience with, the women are vey monogamous, and the men are very much, not. I mean across the board, that’s pretty much-I mean, of course with the younger crowd as well, they’re all concurrent. So yeah. | |

| African Men - You know, every time you ask who does concurrency, I giggle because I think it’s easier to answer, if we asked, who doesn’t. Work with me on this | |

| African Men - I think not only from sitcoms, we see it around us. People do actually engage in that behavior who are not necessarily from our culture, or heritage, and no one frowns upon it as we walk around life. So your psyche just, yeah, accepts it. | |

| Mixed Adult Women - Something happens to one of your parents and at the funeral, and somebody your age shows up and says that’s my dad too or that’s my mom too. My mom mostly no, it’s mostly that’s my dad too. They show up and want to inherit. It’s kind of an extension of those hardships and lifestyle. Culturally, my grandpa had five wives and it was not a secret because that’s a traditional thing. I think the new generation was taught to be monogamous Christians. Otherwise, they’re still trying to be like grandpa. They’re just hiding it. | |

| Mixed Adult Women - It’s the norm I guess for them now. | |

| Mixed Adult Women - I think that the average person my age, if you don’t clearly state that, they are probably going to continue having sex as long as possible. They’re going to try to keep the relationship in the friends-with-benefits zone. Even once you get together, there is no certainty. There isn’t. I’m just saying if you’re not clear with that person, there’s a great chance. | |

| Mixed Adult Women - I’m not from here, but since I’ve been here, I’ve kind of seen what she says. It is kinda everywhere too, but it’s definitely going on. It’s not just the men. I know some women who are just as promiscuous as men. | |

| Mixed Adult Women - It seems to be normal to be that way these days. It’s like everybody’s doing it. No commitment | |

| Mixed Adult Women - I’m 26. I’m saying between the ages of 18 and 30. I think it’s very popular. I think it’s so common among black men in my age group that I would be shocked when I find that it’s not taking place. I think it’s sad, but when you meet, like I know when I date, it’s something I have to tell the guy. I have to explicitly state, “Just me and you are having sex. You’re not to be having sex with somebody else.” It’s sad that you have to state that. It’s sad that you have to say that to someone | |

| Mixed Youth - I think they are being treated like everyone else. My friends, I know a lot of people, everybody, I don’t wanna give their names out, but they-no one really pays attention. If my friend tells me he’s doing this and that, I’m not really gonna be like, hey dude, come on man, don’t do that. I’m just being honest with you, I’d probably say stuff like, I see you man, something like that. I’m not gonna be like stop. That’s not the way that we’re taught to do things. People think it’s cool kind of, from a guy’s perspective. | |

| Mixed Youth - It’s both men and women. | |

| Mixed Youth - It’s socially acceptable nowadays. | |

| Mixed Youth - I’m gonna say it depends on where you are because in different areas and different places - like he said - it’s socially acceptable. | |

| Mixed Youth - Mostly in the suburbs of Seattle they’re gonna defend it and not let it be seen - but in the very poor neighborhood, I think there’s pretty much a lot of people who do it and you can see it. I work at the airport and sometimes I work late nights and I ride the bus and I’ve seen and experienced on the bus rides very late at night - I’m talking about prostitutes and things like that | |

| Mixed Youth - Girls are treated one way and guys are treated another way, but no matter where you’re from sex is sex is sex. There’s only one way to get down that way. It’s so socially acceptable. I’ve got a couple experiences on my own - I’m not gonna go into it - but I think it’s just become too socially acceptable and it’s not that big of a deal to a lot of people anymore. | |

| Mixed Youth - I think it’s everybody - educated people, uneducated, poor people, rich people, you know? In this city I mean it’s everybody. I can’t really say it’s a particular group - maybe in the inner city in the hood, you have people who are doing it more - I mean you see people who are having babies and everything so maybe them. But you can’t really stereotype it. | |

| Mixed Youth - I’ve been everywhere so pretty much everybody does it that is what I would say about it. I’ve been in a white neighborhood, I’ve been in Puerto Rican neighborhoods, I’ve been everywhere and they all do it. It just depends pretty much on how you were raised. That’s all it is really. | |

| Mixed Youth - The majority of society - yes, it is kind of that way. But if it was that way as a society they wouldn’t make movies about it. That’s how acceptable it is with everybody - with a lot of people - not with everybody - but with a lot of people, it is still kinda like, “Damn dude! Homey at least take a shower between them!” | |

| Mixed Youth - My friends always tell me that you need to date more than one guy and stay with one guy. You have to get to know more people. So that’s it I guess. | |

| MSM - I think it’s an expectation that people do it - that people are doing it. Not that it’s a favorable thing, but that people are doing it. It’s how it is - it’s kind of an excepted norm. | |

| MSM - A lot of people in my community are practicing concurrency. My community would be the black community and the gay community - the black gay community. And I think a lot of people are practicing concurrency. I don’t necessarily think it’s something that people are necessarily trying to do. I think concurrency can happen if your single, and you’re just doing what you do. I think concurrency - if it’s happening in a relationship and it’s not talked about that maybe could be a negative thing, but I don’t think it’s necessarily a thing of people being a slut or loose. But I think it happens more often than people wanna talk about. | |

| MSM - It’s pretty much a thing of the 2000’s - this is the day and age - this day and age is what they show you on TV. You can have as much sex as you want as much as you want. They don’t care if it’s safe or not - just have it, and buy my album. That’s pretty much what it portrays on TV. | |

| MSM - Openly. I don’t know if this is so much because of Seattle’s culture, people are a little more liberal, a little more experienced. Maybe because of the people I’m socializing with, they’re more open-minded about certain things. So the fact that they are having multiple partners is almost so normalized, that it’s not like, taboo. And in some cases it’s almost like, if you’re not having multiple partners, then you’re the one missing out. |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant number 5R21 HD057832-02 (to Dr. Andrasik). This publication resulted in part from research supported by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA). We would like to sincerely thank our community members for their vision, guidance, and contributions: Metasabia Afework, Tina Ali, Someireh Amirfaiz, Austin Anderson, Donna Bland, Gary Chovnick, Sita Das, Mary Diggs Hobson, Kiantha Duncan-Woods, Meti Duressa, David Garcia, Yolanda Gill-Masundire, Vanessa Granberry, Joseph Grant, Salem Gugsa, Jsani Henry, Bryan Hill, LaTanya Horace Cheatham, Tamika Jackson, Roxanne Kerani, David Lee, Phyllis Little, Rose Long, Kim Louis, Samuel Makoma, Peter Masundire, Lyungai Mbilinyi, Kenny Joe McMullen, Aaliyah Messiah, Camisha Mitchell, Katie Mitchell, Martin Ndegwa, Michael Neguse, Kaijson Noilmar, Wendy Ono, Arthur Padilla, Warya Pothan, Tonya Raspberry, Caroline Sawe, Ira SenGupta, Cornelius Spears, Solomon Tsegaselassie, Steve Wakefield, Berizaf Weldeargay, Yodit Wongelemegist, Bob Wood, and Negash Zewdie.

Contributor Information

Michele Peake Andrasik, Acting Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Washington, Box 358080, Behavioral Scientist, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue N, LE-500, Seattle, WA 98109-1024, (206) 667-2074, Fax (206) 667-6366, mpeake@u.washington.edu

Caitlin Hughes Chapman, Research Assistant, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Support: 5R21 HD057832-02, Box 359931, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104, Tel: 206-685-4498 / Fax: 206-744-3693, chughesc@uw.edu.

Rachel Clad, Research Coordinator, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Support: 3R21 HD057832-02S2, Box 359931, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104, Tel: 206-685-4498 / Fax: 206-744-3693, cladr@uw.edu.

Kate Murray, Research Scientist, UW/FHCRC Center for AIDS Research, Support: 5P30 AI027757, Box 359931 / Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue / Seattle, WA 98104-2499, Tel: 206-543-8316 / Fax: 206-744-3693, krmurray@uw.edu.

Jennifer Foster, Research Coordinator, PATH, Mail: PO Box 900922 ∣ Seattle, WA 98109, USA, Street: 2201 Westlake Avenue, Suite 200, Seattle, WA 98121, Tel: 206.302.4707 / Fax: 206.285.6619, jfoster@path.org.

Martina Morris, Professor, Department of Sociology and Statistics, University of Washington, Director, Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core, UWCF, CSDE, CFAR, Support: 5R21 HD057832-02, Box 354322, Padelford B211, Seattle, WA 98195-4322, Tel: 206-685-3402 / Fax: 206-685-7419, morrism@uw.edu.

Malcolm R. Parks, Professor, Department of Communication, University of Washington, Support: 5R21 HD057832-02, Box 353740, 340C Communications Bldg., Seattle, WA 98195-3740, Tel: 206-543-2660 / Fax: 206-616-3762, macp@uw.edu.

Ann Elizabeth Kurth, Professor, New York University College of Nursing (NYUCN), Affiliate Professor, UW (School of Nursing; and Dept. of Global Health), Support: Support: 5R21 HD057832-02, 726 Broadway / NY, NY 10003, Tel: 212-998-5316 / Fax: 212-995-3143, akurth@nyu.edu.

References

- Abu-Raddad LJ, Longini IM. No HIV stage is dominant in driving the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(9):1055–61. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f8af84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent Sexual Partnerships among men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(12):2230–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: Sexual networks and social context. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(7suppl):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191:S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;14:155–160. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent Partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;34:423–429. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Bonas DM, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR. Concurrent sexual partnerships among women in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO. Sexual network patterns as determinants of STD rates: paradigm shift in the behavioral epidemiology of STDs made visible. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:262–264. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L, Krebs LU, Bradley A, Gamito E, Osborn K, Dignan MB, Kaur JS. Lessons learned while developing the “Clinical Trials Education for Native Americans” curriculum. Cancer Control. 2003;10(5 suppl):29–36. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Befus M, Willis S, Griffin A, West T, Hader S, Greenberg AE. Use of the community viral load as a population-based biomarker of HIV burden. AIDS. 2012;26(3):345–53. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834de5fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Pilcher CD. Amplified HIV transmission and new approaches to HIV prevention. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(9):1391–1393. doi: 10.1086/429414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, Scheer S, Vittinghoff E, McFarland W, Colfax GN. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in HIV infections in San Francisco. PloS One. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JW, Hallett TB, Garnett GP. Concurrent sexual partnerships and primary HIV infection: a critical interaction. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(4):687–692. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9787-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein H. The Fidelity Fix. New York Times Magazine. 2004 Jun 13; [Google Scholar]

- Garnett GP, Johnson AM. Coining a new term in epidemiology: concurrency and HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:681–683. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Cassels S, Kasprzyk D, Montano DE, Greek A, Morris M. Concurrent Partnerships, Acute Infection and HIV epidemic dynamics among young adults in Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 Dec 30; doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9858-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EC, Halperin DT, Nantulya V, Hogle JA. Uganda’s HIV prevention success: The role of sexual behavior change and the national response. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(4):335–350. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett TB, Aberle-Grasse J, Bello G, Boulos LM, Cayemittes MP, Cheluget B, et al. Declines in HIV prevalence can be associated with changing sexual behaviour in Uganda, urban Kenya, Zimbabwe, and urban Haiti. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82(Suppl):I1–I8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.016014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: The need for new directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DT, Mugurungi O, Hallett TB, Muchini B, Campbell B, Magure T, Benedikt C, Gregson S. A surprising prevention success: Why did the HIV epidemic decline in Zimbabwe? PLOS Med. 2011;8(2):e1000414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RJ, White RG. Amplified HIV transmission during early-stage infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;193(4):604–605. doi: 10.1086/499606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Kalilani-Phiri L. The association of HIV serodiscordance and partnership concurrency in Likoma Island (Malawi) AIDS. 2009;23(10):1285–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832aa85c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth TD, Anderson RM, Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission by stage of infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198(5):687–693. doi: 10.1086/590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Raphael S. The effects of male incarceration dynamics on AIDS infection rates among African-American women and men. [5/7/07];2006 Accessed from http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~ruckerj/johnson_raphael_prison-AIDSpaper6-06.pdf.

- Kretzschmar M, Morris M. Measures of Concurrency in Networks and the spread of infectious disease. Mathematical Biosciences. 1996;133:165–195. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann E, Gagnon J, Michael R, Michaels S. The social organization of Sexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/Ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: A network explanation. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie M, Rosenthal S, Williams B. Concurrency driving the African HIV epidemics: where is the evidenced? Lancet. 2009;374:1420–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie MN, Rosenthal S. Concurrent partnerships as a driver of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa? The evidence is limited. AIDS and Behavior. 2010a;14(1):17–24. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9583-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie MN, Rosenthal S. The concurrency hypothesis in sub-Saharan Africa: Convincing empirical evidence is still lacking. Response to Mah and Halperin, Epstein, and Morris. AIDS and Behavior. 2010b;14:34–37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah TL, Halperin DT. Concurrent sexual partnerships and the HIV epidemics in Africa: evidence to move forward. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):11–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Sex partner concurrency: Measurement, prevalence and correlates among urban 18-39-year-olds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(3):133–143. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Kurth AE, Hamilton DT, Moody J, Wakefield S. Concurrent partnerships and HIV prevalence disparities by race: linking science and public health practice. American Journal of Public Health. 2009 Jun;99(6):1023–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Goodreau S, Moody J. Sexual Networks, Concurrency, and STD/HIV. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, et al., editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent Partnerships and the spread of HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:641–648. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas C. Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Use among Racial/Ethnic Minorities. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. NIH publication 03-3888; 2003. Rev Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Chabot M, Dobransky N, Zimmerman RS. A 10-Year Systematic Review of HIV/AIDS Mass Communication Campaigns: Have we made progress. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14:15–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitsky V, Ndung’u T, Wang R, Bussmann H, Chonco F, Makhema J, De Gruttola V, Walker BD, Essex M. Extended high viremics: a substantial fraction of individuals maintain high plasma viral RNA levels after acute HIV-1 subtype C infection. AIDS. 2011;25(12):1515–22. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471eb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Jr, Vernazza PL, Leu SY, Stewart PW, et al. Brief but efficient: Acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189(10):1785–1792. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton S. Probability of HIV transmission during acute infection in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:677–684. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne DE. Phenomenological research methods. In: Valle RS, Halling S, editors. Existential-Phenomenological perspectives in psychology. New York: plenum Press; 1989. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Powers KA, Ghani AC, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Pettifor AE, Kamanga G, Martinson FEA, Cohen MS. The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi: a modelling study. Lancet. 2011;378:256–268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60842-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Seattle & King County (PHSKC) [1/19/11];First Half of 2010 King County Public Health Epi Report. 2010a http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/communicable/hiv/epi/reports.aspx.

- Public Health Seattle & King County (PHSKC) [1/19/11];HIV Among Foreign Born Blacks: Fact Sheet. 2010b http://www.doh.wa.gov/cfh/hiv/statistics/docs/fs12-10fb.pdf.

- Romer D, Sznitman S, DiClemente R, Salazar LF, Vanable PA, Carey MP, et al. Mass Media as an HIV-Prevention Strategy: Using Culturally Sensitive Messages to Reduce HIV-Associated Sexual Behavior of At-Risk African American Youth. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2150–2159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawers L, Stillwagon E. Concurrent sexual partnerships do not explain the HIV epidemics in Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JD. A tale of two-component generalized HIV epidemics. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):964–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JD, Halperin D, Nantulya V, Potts P, Gayle H, Holmes K. Partner Reduction is Crucial for Balanced “ABC” Approach to HIV Prevention. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:891–893. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7444.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Development Community (SADC) Expert Think Tank Meeting on HIV Prevention in High-Prevalence Countries in Southern Africa; Maseru, Lesotho. May 10–12.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spieldenner AR, Castro CF. Education and Fear: Black and Gay in the Public Sphere of HIV prevention. Communication Education. 2010;59(3):274–281. [Google Scholar]