Abstract

Phages of the P335 species infect Lactococcus lactis and have been particularly studied because of their association with strains of L. lactis subsp. cremoris used as dairy starter cultures. Unlike other lactococcal phages, those of the P335 species may have a temperate or lytic lifestyle, and are believed to originate from the starter cultures themselves. We have sequenced the genome of L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 isolated from fermented corn and found that it contains an integrated P335 species prophage. This 41 kb prophage (Φ KW2) has a mosaic structure with functional modules that are highly similar to several other phages of the P335 species associated with dairy starter cultures. Comparison of the genomes of 26 phages of the P335 species, with either a lytic or temperate lifestyle, shows that they can be divided into three groups and that the morphogenesis gene region is the most conserved. Analysis of these phage genomes in conjunction with the genomes of several L. lactis strains shows that prophage insertion is site specific and occurs at seven different chromosomal locations. Exactly how induced or lytic phages of the P335 species interact with carbohydrate cell surface receptors in the host cell envelope remains to be determined. Genes for the biosynthesis of a variable cell surface polysaccharide and for lipoteichoic acids (LTAs) are found in L. lactis and are the main candidates for phage receptors, as the genes for other cell surface carbohydrates have been lost from dairy starter strains. Overall, phages of the P335 species appear to have had only a minor role in the adaptation of L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains to the dairy environment, and instead they appear to be an integral part of the L. lactis chromosome. There remains a great deal to be discovered about their role, and their contribution to the evolution of the bacterial genome.

Keywords: phage, Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris, dairy, starter culture, genome, integrase, cell wall polysaccharides

Introduction

The role of Lactococcus lactis as the key organism in the initiation of milk fermentation has been known since the work of Joseph Lister in the 1870s when Bacterium lactis was the first bacterium to be isolated in pure culture (Santer, 2010). Today this species is the main constituent of cultures used for the manufacture of a vast range of fermented dairy products, including fermented milks, sour cream, soft and hard cheeses, and lactic casein. The taxonomy of L. lactis is confused by discrepancies between phenotypic and genotypic descriptions but it is apparent that two subspecies exist that correlate with genotype and are known as L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis (Kelly et al., 2010). Both subspecies are used as starters by the dairy industry but the strains with the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype cluster closely together (Rademaker et al., 2007), and are particularly favored for use as defined strain starter cultures for Cheddar cheese production.

The use of defined strain starters began in New Zealand in the 1930s using bacteria selected from mixed strain cultures, and studies of bacteriophages that infect dairy cultures began around the same time (Whitehead and Cox, 1936), as fermentations using single strain starters quickly proved to be susceptible to phage attack. Subsequently, phage resistance and the selection and characterization of phage-unrelated strains, became the major focus of dairy starter culture research (Lawrence et al., 1978), and it was concluded that a relatively small number of significantly different L. lactis subsp. cremoris starter strains exist (Whitehead and Bush, 1957; Lawrence et al., 1978; Kelly et al., 2010). Initial studies investigated whether phages originated from the dairy environment or from the cultures themselves, but eventually the environmental origin came to be regarded as the most significant and a range of measures were developed to control phage attack (Whitehead, 1953). Nevertheless, phage attack, leading to slow or dead vats, remains the leading cause of fermentation problems in the dairy industry. It was also discovered that most starter strains were lysogenized by one or more bacteriophage, and that these temperate phages could be induced, although it was difficult to find strains that they could be propagated on (Huggins and Sandine, 1977; Terzaghi and Sandine, 1981).

Bacteriophages from L. lactis were originally divided into 12 species within the Siphoviridae and Podoviridae based on morphology and DNA homology, and type phages were selected to represent each species (Jarvis et al., 1991). Subsequent studies have refined the number of species to 10 (Deveau et al., 2006), with most of the phage problems encountered in dairy fermentations ascribed to just three species. These are the small isometric-headed 936 and P335 species, and the prolate-headed c2 species. The 936 and c2 species are lytic whereas phages from the P335 species may have a temperate or lytic lifestyle (Braun et al., 1989). Phages of all three species have now had their genomes sequenced and while phages from the 936 and c2 species form distinct but homogeneous groups, the phages from the P335 species are much more heterogeneous and their genomes appear to be mosaic in structure similar to the lambdoid phages. Most studies of phages of the P335 species have focused on their lytic or temperate relationship with L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starter strains. Here we describe a prophage from the genome of a non-dairy L. lactis subsp. cremoris culture and compare its genome organization with a range of other phages of the P335 species from L. lactis.

Materials and methods

Genome sequencing

L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 was originally isolated from kaanga wai (fermented corn) and was chosen for sequencing because in studies comparing multiple L. lactis cultures (Rademaker et al., 2007) it grouped with the L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starter cultures. Its genome sequence was determined using pyrosequencing of 3 kb mate paired-end sequence libraries on a 454 GS FLX platform with titanium chemistry (Macrogen, South Korea). Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 2.5.3 (Roche 454 Life Sciences, USA) resulting in 22 contigs across a single scaffold. Gap closure was managed using the Staden package (Staden et al., 2000), and gaps were closed using additional Sanger sequencing by standard PCR-based techniques. Protein-encoding genes were identified by Glimmer (Delcher et al., 1999) and a GAMOLA/ARTEMIS (Rutherford et al., 2000; Altermann and Klaenhammer, 2003) software suite was used to manage genome annotation. Assignment of protein function to ORFs was performed manually using results from BLASTP, and the COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups, Tatusov et al., 2000), Pfam (Punta et al., 2012), and TIGRFAM (Haft et al., 2013) databases.

Lactococcus lactis genomes

Complete sequences are available for the chromosomes of eight L. lactis strains. For L. lactis subsp. cremoris these are the cheese starter cultures A76 (isolated in France, Bolotin et al., 2012), SK11 (isolated in New Zealand, Makarova et al., 2006) and UC509.9 (isolated in Ireland, Ainsworth et al., 2013), and the plasmid-free reference strain MG1363 (Wegmann et al., 2007). All of these strains originally derive from mixed strain dairy starter cultures. A feature of the three cheese starter cultures is that they harbor several plasmids which enable these strains to metabolize lactose and casein efficiently, and that their chromosomes contain a large number of transposases and pseudogenes. For L. lactis subsp. lactis there are genomes for the plasmid-free reference strain IL1403 which is of dairy origin (Bolotin et al., 2001), and three non-dairy strains, KF147 (Siezen et al., 2010), CV56 (Gao et al., 2011), and IO-1 (Kato et al., 2012).

P335 phage genomes

Table 1 lists the phages belonging to the P335 species for which genome information is available. Three genomes are of lytic phages; P335 (Labrie et al., 2008), 4268 (Trotter et al., 2006), and ul36 (Labrie and Moineau, 2002), with partial genome sequence information also available for an additional lytic phage, Φ 31 (Madsen et al., 2001). Six genomes are from temperate phages that have been induced from their host strain and propagated, usually on either a closely related strain (strain H2 for BK5-T) or a prophage-cured derivative (cured derivative of strain R1 for r1t). Publically available temperate phage genomes are: TP901-1 (Brøndsted et al., 2001), Tuc2009 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_002703), r1t (van Sinderen et al., 2006), BK5-T (Desiere et al., 2001), Φ LC3 (Blatny et al., 2004), and Φ smq86 (Labrie and Moineau, 2007). All of these phages have been studied because of their ability to lyse dairy starter strains, although most have a relatively narrow host range.

Table 1.

Genomes from lytic and induced P335 species phages, and from P335 prophages located in chromosomes of L. lactis strains.

| Phage | Status | Host1 | Size (kb) | Host origin | Accession no.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P335 | Lytic | L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis F7/2 | 34 | Dairy starter | DQ838728 |

| 4268 | Lytic | L. lactis subsp. lactis DPC4268 | 37 | Dairy starter | NC_004746 |

| ul36 | Lytic | L. lactis subsp. cremoris SMQ-86 | 37 | Dairy starter | NC_004066 |

| Φ 31 (fragment) | Lytic | L. lactis subsp. lactis NCK203 | Dairy starter | AJ292531 | |

| TP901-1 | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 | 38 | Dairy starter | NC_002747 |

| Tuc2009 | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris UC509 | 38 | Dairy starter | NC_002703 |

| r1t | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris R1 | 33 | Dairy starter | NC_004302 |

| BK5-T | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris BK5 | 40 | Dairy starter | NC_002796 |

| Φ LC3 | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris IMN-C3 | 32 | Dairy starter | NC_005822 |

| Φ smq86 | Temperate/Induced | L. lactis subsp. cremoris SMQ-86 | 34 | Dairy starter | DQ394810 |

| bIL285 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 | 36 | Dairy starter | AF323668 |

| bIL286 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 | 42 | AF323669 | |

| bIL309 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 | 37 | AF323670 | |

| SK11-2 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris SK11 | 37 | Dairy starter | NC_008527 |

| SK11-3 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris SK11 | 32 | ||

| SK11-4 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris SK11 | 40 | ||

| t712 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 | 42 | Dairy starter | NC_009004 |

| MG-3 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 | 44 | ||

| A76-1 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris A76 | 36 | Dairy starter | NC_017492 |

| A76-2 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris A76 | 38 | ||

| pp1 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis KF147 | 35 | Bean sprouts | NC_013656 |

| pp2 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis KF147 | 54 | ||

| pi1 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis CV56 | 35 | Human vagina | NC_017486 |

| pi2 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis CV56 | 37 | ||

| pi3 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis CV56 | 34 | ||

| ps3 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. lactis IO-1 | 36 | Kitchen drain | AP012281 |

| Φ KW2 | Prophage | L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 | 41 | Fermented corn | CP004884 |

For lytic phages the host is the strain used for phage propagation; for temperate/induced phages the host is the strain the phage was induced from with propagation on a closely related strain or a cured derivative of the host; for prophages the host is the strain containing the integrated phage genome and these have not been propagated.

Accession numbers are for the phage genome where that is separately available, or for the bacterial genome containing the integrated prophage.

Seventeen complete prophages were identified in L. lactis genomes, and with the exception of UC509.9 (a derivative of UC509 that has been cured of the Tuc2009 prophage, Ainsworth et al., 2013), all of the sequenced L. lactis strains have at least one full-length P335 species prophage integrated into their chromosome (Table 1). The prophages from strains IL1403, MG1363, and SK11 have been described in detail previously (Chopin et al., 2001; Ventura et al., 2007). Phage remnants are also found in these chromosomes, but were not included in the analysis as they have been shown to form a separate subgroup (Ventura et al., 2007).

Functional genome distribution of 26 Lactococcus lactis P335 phages

Publicly available phage genomes were downloaded in Genbank format from the NCBI genome database. Similarly, publicly available Lactococcus lactis genomes were downloaded in Genbank format, and integrated prophage genomes identified. All phage genomes were then automatically annotated using GAMOLA (Altermann and Klaenhammer, 2003). Predicted ORFeomes of all genomes were subjected to a functional genome distribution analysis (Altermann, 2012) and the resulting distance matrix was imported into MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011). The functional distribution was visualized using the UPGMA method (Sneath and Sokal, 1962).

Results

Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 genome sequence

The genome of L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 consists of a 2,427,048 bp circular chromosome, with a G + C content of 36.65%. KW2 has 61 tRNA genes and 2278 coding sequences (CDS) were predicted. The chromosomal gene content of KW2 is highly similar to L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starter strains, but KW2 has no plasmids, and the chromosome has no transposases and few pseudogenes. The genome sequence of L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 has been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number CP004884.

Prophage ϕKW2 genome organization

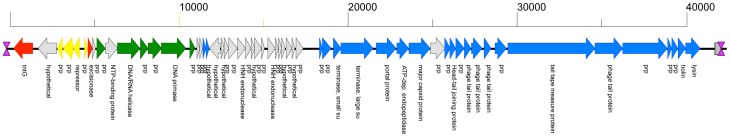

The KW2 chromosome contains an integrated 41 kb prophage genome (Φ KW2, kw2_1785 to _1841). The consolidated gene model (Figure 1) shows that Φ KW2 harbors 57 ORFs, for 22 of which a predicted function could be assigned. A further 28 ORFs could be linked to phage-related homologs without a described function. All ORFs are on the same strand except for a single hypothetical protein (kw2_1822) and the ORFs involved in establishment and maintenance of lysogeny. The phage ORFs are flanked by 22-bp sequences indicative of attL and attR sites. A full list of the predicted proteins that are encoded by the Φ KW2 genome is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Genome organization of ϕKW2. ORFs are drawn to scale and annotations are shown in vertical text. ORFs which show a high level of homology (average of >95% amino acid identity) to ORFs present in other L. lactis P335 phage genomes are colored as follows: Red, A76-1; Yellow, bIL312; Green, Φ 31; Blue, MG-3, and other phages belonging to Group 3 from Figure 2. ORFs which match to hypothetical proteins or to other phages are shown in gray. The phage left and right attachment sites are indicated by purple hourglass symbols, respectively. A predicted unspecified tRNA is shown as a gray box. The absolute size of the phage genome is indicated as a horizontal bar above the genome map, and the numbers indicate nucleotide position. prp, phage-related protein; su, sub unit.

Table 2.

Predicted proteins encoded by the prophage ϕKW2.

| ORF | Annotation | Size (aa) | Best blast match | aa id/sim (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| attR aaaggggcaaaaaaggggcata | ||||

| 1785 | Phage lysin glycoside hydrolase GH25 family | 287 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2082 | 99/99 |

| 1786 | Phage holin | 150 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2083 | 97/98 |

| 1787 | Phage-related protein | 116 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2084 | 89/96 |

| 1788 | Phage-related protein | 78 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2085 | 92/97 |

| 1789 | Phage tail fiber protein1 | 881 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2086 | 85/92 |

| 1790 | Phage distal tail protein | 548 | BK5-Tp16 | 96/97 |

| 1791 | Phage tail tape measure protein | 1719 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2089 | 89/94 |

| 1792 | Phage-related protein | 225 | KF147. pp2 pp224 | 99/99 |

| 1793 | Phage tail protein | 138 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2090 | 99/99 |

| 1794 | Phage tail protein | 211 | KF147. pp2 pp226 | 92/94 |

| 1795 | Phage tail protein | 131 | KF147. pp2 pp227 | 98/99 |

| 1796 | Phage-related protein | 168 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2093 | 100 |

| 1797 | Phage head-tail joining protein | 116 | IL1403. bIL286 Orf47 | 97/97 |

| 1798 | Phage-related protein | 107 | IL1403. bIL286 Orf46 | 93/97 |

| 1799 | Phage-related protein | 288 | IL1403. bIL285 Orf45 | 92/96 |

| 1800 | Phage major capsid protein | 419 | KF147. pp2, pp231 | 90/95 |

| 1801 | Phage atp-dependent endopeptidase | 234 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2097 | 99/99 |

| 1802 | Phage portal protein | 390 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2098 | 100 |

| 1803 | Phage terminase large subunit | 636 | 4268 | 97/99 |

| 1804 | Phage terminase small subunit | 151 | 4268 | 99/99 |

| 1805 | Phage-related protein | 172 | BK5-Tp63 | 99/99 |

| 1806 | Phage-related protein | 58 | IL1403. bIL286 Orf38 | 95/95 |

| 1807 | Phage-related protein | 141 | MG1363. t712 llmg_0821 | 98/100 |

| 1808 | Hypothetical protein | 53 | CV56. pi3 CVCAS_2130 | 92/98 |

| 1809 | Phage-related protein | 115 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2107 | 36/63 |

| 1810 | Hypothetical protein | 71 | LLCRE1631_01453 | 93/99 |

| 1811 | Phage-related protein | 60 | 4268 | 80/87 |

| 1812 | Phage-related protein | 61 | IL1403. bIL309 Orf28 | 79/87 |

| 1813 | Phage-related HNH endonuclease family protein | 147 | Enterococcus phage EFRM31 | 59/69 |

| 1814 | Phage-related protein | 57 | Lactococcus garvieae DCC43 | 75/90 |

| 1815 | Phage-related protein | 142 | KF147. pp1 pp123 | 40/57 |

| 1816 | Hypothetical protein | 66 | Lactococcus garvieae DCC43 | 90/92 |

| 1817 | Phage-related protein | 117 | 4268 | 62/72 |

| 1818 | Phage-related HNH endonuclease family protein | 151 | Enterococcus phage EFRM31 | 60/70 |

| 1819 | Phage-related protein | 175 | A76. A76-1 llh_3320 | 50/61 |

| 1820 | Phage-related protein | 93 | IL1403. bIL285 Orf26 | 96/98 |

| 1821 | Hypothetical protein | 60 | unknown | |

| 1822 | Hypothetical protein | 210 | Geobacter metallireducens GS-15 | 32/57 |

| 1823 | Hypothetical protein | 63 | MG1363. MG-3 | 95/95 |

| 1824 | Phage-related protein | 65 | MG1363. MG-3 llmg_2117 | 100 |

| 1825 | Phage-related protein | 56 | IL1403. bIL285 Orf24 | 86/89 |

| 1826 | Phage-related protein | 57 | IL1403. bIL285 Orf22 | 84/96 |

| 1827 | Phage-related protein | 103 | Φ 31 | 89/93 |

| 1828 | Phage-related DNA primase | 487 | Φ 31 | 98/99 |

| 1829 | Phage-related protein | 268 | Φ 31 | 98/99 |

| 1830 | Phage-related protein | 150 | Φ 31 | 99/99 |

| 1831 | Phage DNA/RNA helicase | 448 | Φ 31 | 98/99 |

| 1832 | Phage nucleotide-binding protein | 239 | Streptococcus porcinus str. Jelinkova 176 | 90/96 |

| 1833 | Phage-related protein | 169 | Φ 31 | 98/99 |

| 1834 | Phage-related protein | 56 | IL1403. bIL309 Orf10 | 95/98 |

| 1835 | Excisionase | 86 | A76. A76-1 llh_3245 | 98/100 |

| 1836 | Phage-related protein | 63 | IL1403. bIL312 Orf6 | 98/100 |

| 1837 | Phage repressor | 122 | IL1403. bIL312 Orf5 | 90/96 |

| 1838 | Phage-related protein | 195 | IL1403. bIL312 Orf4 | 90/95 |

| 1839 | Phage-related protein | 98 | IL1403. bIL312 Orf3 | 99/100 |

| 1840 | Hypothetical protein | 364 | Streptococcus oralis SK304 | 59/80 |

| 1841 | Phage integrase | 379 | A76. A76-1 llh_3210 | 99/99 |

| attL aaaggggcactaaaggggcata |

This is much smaller than the corresponding protein predicted from MG-3 (881 vs. 1617 aa).

Comparison of P335 phage genomes

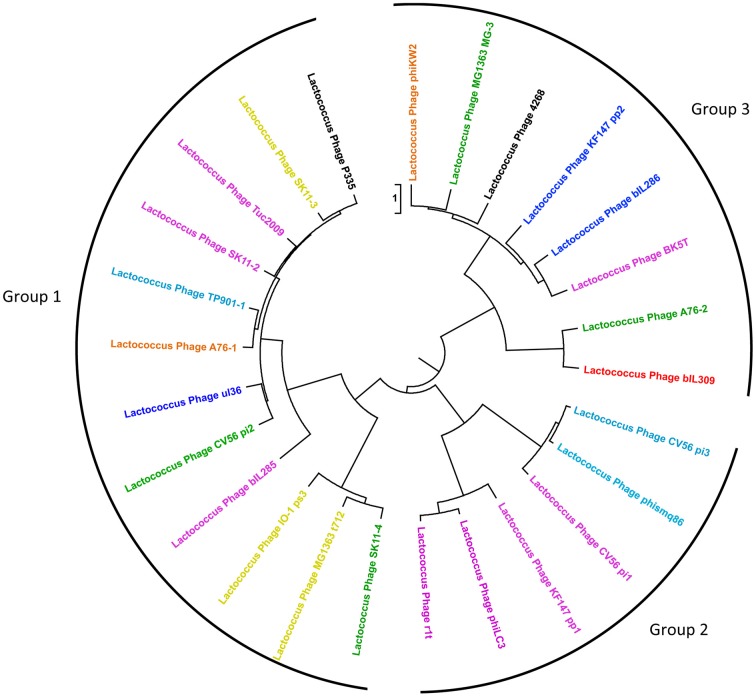

Functional genome distribution was used to compare the genomes of the phages belonging to the P335 species. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 2. The 26 phage genomes fall into three broad groups which show a close resemblance to those previously described by others (Trotter et al., 2006; Ventura et al., 2007; Samson and Moineau, 2010). Recently two lytic phages isolated in North America have been sequenced and assigned to a fourth P335 phage group (Mahoney et al., 2013b). The region of the genome devoted to morphogenesis genes is the most conserved (Labrie et al., 2008). From current sequence data the only gene that is conserved among most phages of the P335 species is that for a dUTPase (Labrie and Moineau, 2002). The phage dUTPase is highly conserved at nucleotide and amino acid levels, but differs significantly from the chromosomal dut gene. A phage-like dUTPase is found in each prophage from the dairy L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains but is not part of the Φ KW2 genome, suggesting that its acquisition may be associated with adaptation to the dairy environment. The role of the phage dUTPase is not known, but it is hypothesized that dUTPases are involved in controlling various cellular processes (Penadés et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Functional genome distribution of 26 Lactococcus lactis P335 phage genomes. Comparison of the complete ORFeomes of all P335 species phage and prophage genomes. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the functional distances used to infer the distribution tree. Three major clusters were identified and are depicted as Groups 1, 2, and 3. The coloring of individual phage relates to their predicted site for chromosomal integration (see Figure 3) as follows: Red, site 1; Yellow, site 2; Dark blue, site 3; Purple, site 4; Orange, site 5; Green, site 6; Blue, site 7; Black, lytic phage with no integrase gene. Although ul36 is a lytic phage it retains an integrase indicating that it may not have lost the ability to lysogenize. This analysis is based on the position of the prophage in the various L. lactis genomes and on the high level of conservation seen between the integrases of the phages that integrate at each specific site.

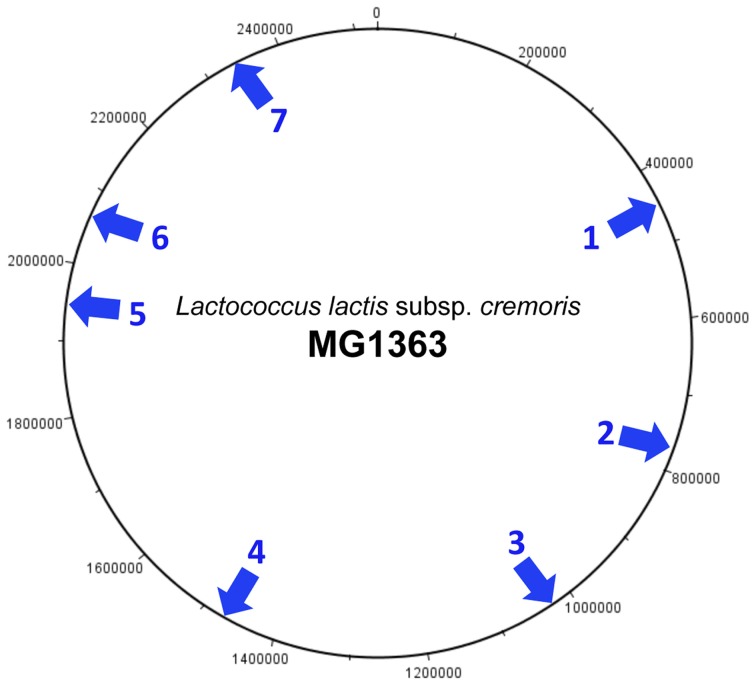

Chromosomal integration

Analysis of the sequenced L. lactis genomes shows that prophage integration is not random but occurs at a limited number of specific sites on the host chromosome. Currently seven different sites have been identified (Figure 3) and each is associated with a highly conserved integrase. The most common location for phage integration is site 4 between the rex and radC genes. There is no relationship between the three groups of phages belonging to the P335 species and the integrase that is present (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Integration sites of P335 species prophages on the L. lactis subsp. cremoris chromosome. The chromosome of MG1363 is used as a reference. MG1363 is described as a phage- and plasmid-cured derivative of NCDO712, and the genome of the parent strain contains an additional prophage predicted to be integrated at site 7 (Le Bourgeois et al., 2000). The integration sites are located as follows: (1) Adjacent to the tRNA-Arg gene located between llmg_0461 (lytR) and llmg_0462 (truA). (2) Between llmg_0789 (rbsB) and llmg_0856. Location of phage t712. (3) Between llmg_1069 and llmg_1079. (4) Between llmg_1514 (rex) and llmg_1515 (radC). (5) Between llmg_1968 and llmg_1969 (sufB). This site is not present in subsp. lactis strains. (6) Between llmg_2081 (sunL) and llmg_2143. Location of phage MG-3. (7) Between llmg_2406 (comGC) and llmg_2407 (comGB).

Host specificity and phage receptors

Phage infection requires the recognition of receptors on the bacterial cell surface by receptor-binding proteins (RBPs) that are part of the phage tail structure. The RBP from TP901-1 has been characterized and forms part of a complex baseplate structure (Spinelli et al., 2006; Bebeacua et al., 2010; 2013). TP901-1 and the closely related Tuc2009 have similar structural tail proteins, but different host ranges and RBPs (Vegge et al., 2006), and based on their genome sequences other phages of the P335 species are also predicted to have different RBPs. The RBPs are known to bind to carbohydrate cell surface receptors but the exact nature of these remains unknown. However, analysis of the genome of L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 suggests that there are possibly four different cell wall polysaccharides (CWP) synthesized by the cell.

L. lactis strains all contain a cluster of >20 genes (kw2_0186-_0208) which together determine the biosynthesis of a CWP that forms a pellicle on the cell surface, and is believed to have a role as a bacteriophage receptor for 936 phages (Mahoney et al., 2013a). Genes encoding the biosynthesis and transfer of rhamnose are located at one end of this gene cluster and appear to be strongly conserved, but the remainder of the genes vary between the different strains. This variability makes this CWP a suitable candidate as a receptor for phages of the P335 species. A second cluster of potential CWP biosynthesis genes is present in KW2 (kw2_2123-_2131), but some of these are pseudogenes in the L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy strains, and so this CWP seems an unlikely candidate as a phage receptor as it is probably not produced in all strains.

It is reported that the most likely receptors are believed to be glycerol- or phosphoglycerol-containing wall teichoic acids (WTA) or lipoteichoic acids (LTAs), as their likely variable structures could determine strain specificity (Spinelli et al., 2006). Despite this, little is known about teichoic acid production by L. lactis. Structures have been determined for the LTA and extracellular (wall) teichoic acid components of L. lactis G121 (Fischer et al., 2011, 2012). This strain was isolated from a cowshed and has been shown to have allergy-protective properties, but the teichoic acids are likely to be different to those from the L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starter strains used in most phage studies.

Analysis of L. lactis genomes shows that genes for the biosynthesis of WTA occur as a large cluster in the plant L. lactis strain KF147 (Siezen et al., 2011) and also in KW2 (kw2_0901 to _0922). The genes at either end of the cluster which encode the assembly and export functions are conserved but the remaining genes, presumed to determine the sugar composition, differ. The situation is drastically different with the L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starter strains. In MG1363 these central genes have been replaced by transposases while in SK11, A76, and UC509.9 only the genes at the ends of the cluster remain. It may be concluded that these dairy strains no longer produce WTA, and it is unlikely to be the phage receptor. How this loss of WTA contributes to the phage resistance phenotype of dairy strains remains to be determined.

Genes encoding the biosynthesis of LTA have been determined for some Gram positive bacteria (Reichmann and Gründling, 2011) but have not been characterized in L. lactis. However, a lipoteichoic acid synthase (LtaS), and two glycolipid biosynthesis glycosyltransferases (LafA and LafB) have been identified in the A76 genome and these are conserved in the other L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains including KW2 (kw2_0755, and kw2_2197-_2198). Other genes involved in biosynthesis of the carbohydrate moieties of the LTA remain to be identified. These strains also have the dltA-D operon which mediates the D-alanylation of LTA and contributes to the cell surface properties (Giaouris et al., 2008). Consequently LTA is a candidate for a cell surface receptor likely to be recognized by phages of the P335 species, although it appears to lack the necessary strain variability. Consequently accurate identification of the host receptor awaits further study.

Phages of the P335 species as agents of gene transfer and chromosomal rearrangement

Transduction of genetic information by temperate phages has been described for lactococci and used to study plasmid-associated lactose and proteinase phenotypes in NCDO712 and related strains (Gasson, 1990). Recently, Wegmann et al. (2012) used plasmid transduction by the Φ TP712 (t712) phage in their analysis of the pLP712 plasmid from NCDO712, but otherwise transduction has been seldom used with L. lactis. There is no information available on transduction by temperate phages from other lactococcal strains, and consequently their role in horizontal gene transfer is not known. Lysogenic conversion can be viewed as a type of specialized transduction, and in the Gram positive pathogens Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, lysogenic conversion genes involved in virulence are found located distal to the phage lysin. Examination of the prophages from the dairy L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains suggests that lysogenic conversion is not common. However, the t712 prophage found in MG1363 does have an abortive infection gene located between the lysin and attR site (Ventura et al., 2007).

Analysis of the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genomes shows that P335 species prophages can be involved in mediating significant changes to chromosomal architecture. In L. lactis subsp. cremoris A76 the prophage integration sites 1 and 6 are found at the ends of a chromosomal rearrangement. The chromosome of strain A76 has truncated integrase, repressor and phage lysin genes adjacent to the lytR gene (llh_2555, site 1). This region also contains several transposases and then joins to the ribosomal RNA small subunit methyltransferase B gene (sunL, llh_2615, site 6). Phage A76-2 is located at the other end of the chromosomal rearrangement. The phage integrase (llh_10885) is adjacent to the A76 homolog of llmg_2143 (llh_10890, site 6), while the lysin gene (llh_10615) is separated from truA (llh_10580, site 1) by a transposase and other hypothetical proteins. A similar situation possibly applies with other L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains HP and FG2 (Kelly et al., 2010) that show similar chromosomal rearrangements to strain A76.

Discussion

Phages that attack Lactococcus lactis dairy starter cultures remain the largest single cause of industrial milk fermentation problems and result in significant economic losses. While most problems result from infection by virulent 936 and c2 species phages, (Madera et al., 2004), phages of the P335 species are also of interest as they likely originate from the starter cultures themselves. However, it is not clear what proportion of significant problems result from the phages of the P335 species. While some P335 phages have adopted a lytic lifestyle, it is possible that this is a relatively rare event, as the lytic P335 phages have a narrow host range (Moineau et al., 1996), and it has proved difficult to find propagation hosts for temperate phages that have been induced from L. lactis dairy strains. Nevertheless, Labrie and Moineau (2007) have clearly shown how a lytic P335 phage can exchange functional modules with an integrated prophage to rapidly generate novel combinations with altered properties.

Most studies of phages belonging to the P335 species have been in the context of their association with dairy strains of L. lactis subsp. cremoris, and here we report the genome sequence of L. lactis subsp. cremoris KW2 that was isolated from fermented corn. The most notable feature of the KW2 chromosome is that it does not show the high numbers of transposases and pseudogenes characteristic of L. lactis subsp. cremoris dairy starters, but it does contain a single integrated prophage (Φ KW2). Phage evolution occurs by the rearrangement of functional modules, and it seems clear that phages are able to mix-and-match these modules to produce a variety of different combinations. Φ KW2 serves as an example of this as its mosaic structure appears little different from the prophages found in dairy starters, and its various functional modules show very high homology to known dairy phages. The integrase and excisionase (which both match to the A76-1 prophage), the early gene control module including the phage repressors (matches to the P335 phage remnant bIL312 found in the IL1403 genome), and the DNA replication module (matches to the replication genes from the lytic phage Φ 31) are located at one end of the genome. The proteins predicted to be encoded by the central region of the genome show only weak homology mainly to proteins from various phage genomes, and this is typical of other phages from the P335 species. The remaining three modules for DNA packaging, phage structural components (including head and tail morphogenesis and host specificity), and cell lysis are found at the other end of the genome and almost all of the genes in this region show high homology to phage MG-3 from the MG1363 genome and to other phages that make up Group 3 in Figure 2.

The ability of phages of the P335 species to shuffle their various modules means that no L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains can be said to be truely phage-unrelated. The integrases are a good example as they enable phages to insert at a limited number of specific sites and yet can be partnered with a diversity of different modules as shown in Figure 2. Using conserved primer sequences from four P335 phages that insert at integration site 4 (Tuc2009, r1t, BK5-T, and Φ LC3), O'Sullivan et al. (2000) showed that 19 of 31 cheese-making lactococcal strains gave a product of the expected size indicating the presence of a specific integrase gene, and by implication a prophage inserted at this location. The lytic behavior of these strains could be correlated with the presence of this prophage sequence.

It can be concluded from this that P335 species prophages are an integral part of the Lactococcus lactis genome, and their interaction can take several different forms. The prophage may be induced from the genome and in some cases become a lytic phage that is unable to relysogenize. Prophages may also mediate chromosomal rearrangement as appears to be the case for L. lactis subsp. cremoris A76, or acquire lysogenic conversion genes that modify bacterial properties. In the case of dairy starter cultures prophages may also influence important industrial properties of the strains such as phage resistance and autolysis. Overall it is difficult to quantify the effect of prophage genomes, and it appears most likely that they have co-evolved together with the bacterial genome. The observation that many of the prophages in dairy strains of L. lactis subsp. cremoris contain transposases suggests that prophage genomes are exposed to the same selection as the host genome, and that prophages may have had only a minor role in the adaptation of Lactococcus lactis strains to the dairy environment.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the AgResearch Curiosity Fund.

References

- Ainsworth S., Zomer A., de Jager V., Bottacini F., van Hijum S. A. F. T., Mahoney J., et al. (2013). Complete genome of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC509.9, host for a model lactococcal P335 bacteriophage. Genome Announc. 1, e00119–e00112 10.1128/genomeA.00119-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altermann E. (2012). Tracing lifestyle adaptation in prokaryotic genomes. Front. Microbiol. 3:48 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altermann E., Klaenhammer T. (2003). GAMOLA: a new local solution for sequence annotation and analyzing draft and finished prokaryotic genomes. Omics 7, 161–169 10.1089/153623103322246557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeacua C., Bron P., Lai L., Vegge C. S., Brøndsted L., Spinelli S., et al. (2010). Structure and molecular assignment of lactococcal phage TP901-1 baseplate. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39079–39086 10.1074/jbc.M110.175646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeacua C., Lai L., Vegge C. S., Brøndsted L., van Heel M., Veesler D., et al. (2013). Visualizing a complete Siphoviridae member by single-particle electron microscopy: the structure of lactococcal phage TP901-901. J. Virol. 87, 1061–1068 10.1128/JVI.02836-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatny J. M., Godager L., Lunde M., Nes I. F. (2004). Complete genome sequence of the Lactococcus lactis temperate phage Φ LC3: comparative analysis of Φ LC3 and its relatives in lactococci and streptococci. Virology 318, 231–244 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A., Quinquis B., Ehrlich D. S., Sorokin A. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris A76. J. Bacteriol. 194, 1241–1242 10.1128/JB.06629-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A., Wincker P., Mauger S., Jaillon O., Malarme K., Weissenbach J., et al. (2001). The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11, 731–753 10.1101/gr.GR-1697R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Hertwig S., Neve H., Geis A., Teuber M. (1989). Taxonomic differentiation of bacteriophages of Lactococcus lactis by electron microscopy, DNA-DNA hybridization, and protein profiles. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135, 2551–2560 [Google Scholar]

- Brøndsted L., Østergaard S., Pedersen M., Hammer K., Vogensen F. K. (2001). Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of the temperate bacteriophage TP901-1: evolution, structure, and genome organization of lactococcal bacteriophages. Virology 283, 93–109 10.1006/viro.2001.0871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopin A., Bolotin A., Sorokin A., Ehrlich S. D., Chopin M.-C. (2001). Analysis of six prophages in Lactococcus lactis IL1403: different genetic structure of temperate and virulent phage populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 644–651 10.1093/nar/29.3.644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher A., Harmon D., Kasif S., White O., Salzberg S. (1999). Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4636–4641 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiere F., Mahanivong C., Hillier A. J., Chandry P. S., Davidson B. E., Brüssow H. (2001). Comparative genomics of lactococcal phages: insight from the complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis phage BK5-T. Virology 283, 240–252 10.1006/viro.2001.0857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H., Labrie S. J., Chopin M. C., Moineau S. (2006). Biodiversity and classification of lactococcal phages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4338–4346 10.1128/AEM.02517-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K., Stein K., Ulmer A. J., Lindner B., Heine H., Holst O. (2011). Cytokine-inducing lipoteichoic acids of the allergy-protective bacterium Lactococcus lactis G121 do not activate via Toll-like receptor 2. Glycobiology 21, 1588–1595 10.1093/glycob/cwr071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K., Vinogradov E., Lindner B., Heine H., Holst O. (2012). The structure of the extracellular teichoic acids from the allergy-protective bacterium Lactococcus lactis G121. Biol. Chem. 393, 749–755 10.1515/hsz-2012-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Lu Y., Teng K.-L., Chen M.-L., Zheng H.-J., Zhu Y.-Q., et al. (2011). Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CV56, a probiotic strain isolated from the vagina of healthy women. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2886–2887 10.1128/JB.00358-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasson M. J. (1990). In vivo genetic systems in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87, 43–60 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaouris E., Briandet R., Meyrand M., Courtin P., Chapot-Chartier M.-P. (2008). Variations in the degree of D-alanylation of teichoic acids in Lactococcus lactis alter resistance to cationic antimicrobials but have no effect on bacterial surface hydrophobicity and charge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4764–4767 10.1128/AEM.00078-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft D. H., Selengut J. D., Richter R. A., Harkins D., Basu M. K., Beck E. (2013). TIGRFAMs and Genome properties in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D387–D395 10.1093/nar/gks1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins A. R., Sandine W. E. (1977). Incidence and properties of temperate bacteriophages induced from lactic streptococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 33, 184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis A. W., Fitzgerald G. F., Mata M., Mercenier A., Neve H., Powell I. B., et al. (1991). Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology 32, 2–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Shiwa Y., Oshima K., Machii M., Araya-Kojima T., Zendo T., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis IO-1, a lactic acid bacterium that utilizes xylose and produces high levels of L-lactic acid. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2102–2103 10.1128/JB.00074-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W. J., Ward L. J. H., Leahy S. C. (2010). Chromosomal diversity in Lactococcus lactis and the origin of dairy starter cultures. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 729–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie S., Moineau S. (2002). Complete genomic sequence of bacteriophage ul36: demonstration of phage heterogeneity within the P335 quasi-species of lactococcal phages. Virology 296, 308–320 10.1006/viro.2002.1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie S. J., Josephsen J., Neve H., Vogensen F. K., Moineau S. (2008). Morphology, genome sequence, and structural proteome of type phage P335 from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4636–4644 10.1128/AEM.00118-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie S. J., Moineau S. (2007). Abortive infection mechanisms and prophage sequences significantly influence the genetic makeup of emerging lytic lactococcal phages. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1482–1487 10.1128/JB.01111-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R. C., Heap H. A., Limsowtin G., Jarvis A. W. (1978). Cheddar cheese starters: current knowledge and practices of phage characteristics and strain selection. J. Dairy Sci. 61, 1181–1191 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(78)83703-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourgeois P., Daveran-Mingot M.-L., Ritzenthaler P. (2000). Genome plasticity among related Lactococcus strains: identification of genetic events associated with macrorestriction polymorphisms. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2481–2491 10.1128/JB.182.9.2481-2491.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madera C., Monjardín C., Suárez J. E. (2004). Milk contamination and resistance to processing conditions determine the fate of Lactococcus lactis bacteriophages in dairies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 7365–7371 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7365-7371.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen S. M., Mills D., Djordjevic G., Israelsen H., Klaenhammer T. R. (2001). Analysis of the genetic switch and replication region of a P335-type bacteriophage with an obligate lytic lifestyle on Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 1128–1139 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1128-1139.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J., Kot W., Murphy J., Ainsworth S., Neve H., Hansen L. H., et al. (2013a). Investigation of the relationship between lactococcal cell wall polysaccharide genotype and 936 phage receptor binding protein phylogeny. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4385–4392 10.1128/AEM.00653-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J., Martel B., Tremblay D. M., Neve H., Heller K. J., Moineau S., et al. (2013b). Identification of a new P335 subgroup through molecular analysis of lactococcal phages Q33 and BM13. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4401–4409 10.1128/AEM.00832-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K., Slesarev A., Wolf Y., Sorokin A., Mirkin B., Koonin E., et al. (2006). Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15611–15616 10.1073/pnas.0607117103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moineau S., Borkaev M., Holler B. J., Walker S. A., Kondo J. K., Vedamuthu E. R., et al. (1996). Isolation and characterization of lactococcal bacteriophages from cultured buttermilk plants in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 79, 2104–2111 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76584-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan D., Ross R. P., Fitzgerald G. F., Coffey A. (2000). Investigation of the relationship between lysogeny and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in cheese using prophage-targeted PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2192–2198 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2192-2198.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penadés J. R., Donderis J., García-Caballer M., Tormo-Más M. Á., Marina A. (2013). dUTPases, the unexplored family of signalling molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 163–170 10.1016/j.mib.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., et al. (2012). The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–D301 10.1093/nar/gkr1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker J. L. W., Herbert H., Starrenburg M. J. C., Naser S. M., Gevers D., Kelly W. J., et al. (2007). Diversity analysis of dairy and nondairy Lactococcus lactis isolates, using a novel multilocus sequence analysis scheme and (GTG)5-PCR fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7128–7137 10.1128/AEM.01017-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann N. T., Gründling A. (2011). Location, synthesis and function of glycolipids and polyglycerolphosphate lipoteichoic acid in Gram-positive bacteria of the phylum Firmicutes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 319, 97–105 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02260.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K., Parkhill J., Crook J., Horsnell T., Rice P., Ranjandream M.-A., et al. (2000). Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16, 944–945 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson J. E., Moineau S. (2010). Characterization of Lactococcus lactis phage 949 and comparison with other lactococcal phages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6843–6852 10.1128/AEM.00796-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer M. (2010). Joseph Lister: first use of a bacterium as a ‘model organism’ to illustrate the cause of infectious disease of humans. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 64, 59–65 10.1098/rsnr.2009.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen R. J., Bayjanov J., Renckens B., Wels M., van Hijum S. A. F. T., Molenaar D., et al. (2010). Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KF147, a plant-associated lactic acid bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2649–2650 10.1128/JB.00276-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen R. J., Bayjanov J. R., Felis G. E., van der Sijde M. R., Starrenburg M., Molenaar D., et al. (2011). Genome-scale diversity and niche adaptation analysis of Lactococcus lactis by comparative genome hybridization using multi-strain arrays. Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 383–402 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00247.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath P. H., Sokal R. R. (1962). Numerical taxonomy. Nature 193, 855–860 10.1038/193855a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli S., Campanacci V., Blangy S., Moineau S., Tegoni M., Cambillau C. (2006). Modular structure of the receptor binding proteins of Lactococcus lactis phages. The RBP structure of the temperate phage TP901-901. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14256–14262 10.1074/jbc.M600666200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staden R., Beal K. F., Bonfield J. K. (2000). The Staden package, 1998. Methods Mol. Biol. 132, 115–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R., Galperin M., Natale D., Koonin E. (2000). The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 33–36 10.1093/nar/28.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi B. E., Sandine W. E. (1981). Bacteriophage production following exposure of lactic streptococci to ultraviolet radiation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 122, 305–311 [Google Scholar]

- Trotter M., McAuliffe O., Callanan M., Edwards R., Fitzgerald G. F., Coffey A., et al. (2006). Genome analysis of the obligately lytic bacteriophage 4268 of Lactococcus lactis provides insight into its adaptable nature. Gene 366, 189–199 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Sinderen D., Karsens H., Kok J., Terpstra P., Ruiters M. H., Venema G., et al. (2006). Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol. Microbiol. 19, 1343–1355 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegge C. S., Vogensen F. K., McGrath S., Neve H., van Sinderen D., Brøndsted L. (2006). Identification of the lower baseplate protein as the antireceptor of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophages TP901-1 and Tuc2009. J. Bacteriol. 188, 55–63 10.1128/JB.188.1.55-63.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M., Zomer A., Canchaya C., O'Connell-Motherway M., Kuipers O., Turroni F., et al. (2007). Comparative analyses of prophage-like elements present in two Lactococcus lactis strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7771–7780 10.1128/AEM.01273-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann U., O'Connell-Motherway M., Zomer A., Buist G., Shearman C., Canchaya C., et al. (2007). Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3256–3270 10.1128/JB.01768-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann U., Overweg K., Jeanson S., Gasson M., Shearman C. (2012). Molecular characterization and structural instability of the industrially important composite metabolic plasmid pLP712. Microbiology 158, 2936–2945 10.1099/mic.0.062554-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead H. R. (1953). Bacteriophage in cheese manufacture. Bacteriol. Rev. 17, 109–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead H. R., Bush E. J. (1957). Phage-organism relationships among strains of Streptococus cremoris: the selection of strains as cheese starters. J. Dairy Res. 24, 381–386 10.1017/S0022029900008931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead H. R., Cox G. A. (1936). Phage phenomena in cultures of lactic streptococci. J. Dairy Res. 7, 55–62 10.1017/S0022029900001655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]