Abstract

Arthropods living on plants are able to digest plant biomass with the help of microbial flora in their guts. This study considered three arthropods from different niches - termites, pill-bugs and yellow stem-borers - and screened their guts for cellulase producing microbes. Among 42 unique cellulase-producing strains, 50% belonged to Bacillaceae, 26% belonged to Enterobacteriaceae, 17% belonged to Microbacteriaceae, 5% belonged to Paenibacillaceae and 2% belonged to Promicromonosporaceae. The distribution of microbial families in the three arthropod guts reflected differences in their food consumption habits. Most of the carboxymethylcellulase positive strains also hydrolysed other amorphous substrates such as xylan, locust bean gum and β-D-glucan. Two strains, A11 and A21, demonstrated significant activity towards Avicel and p-nitrophenyl-β-D-cellobiose, indicating that they express cellobiohydrolase. These results provide insight into the co-existence of symbionts in the guts of arthropods and their possible exploitation for the production of fuels and chemicals derived from plant biomass.

Rising concern over the cost and sustained availability of fossil fuels has increased demand for the development of alternative and preferably renewable fuel resources, with lignocellulosic biomass as one promising resource1,2. Lignocellulose represents ~90% of the dry weight of all plant materials3, is primarily composed of the sugar polymers cellulose (35–50%) and hemicellulose (20–35%) together with lignin (5–30%) that provides structural support for the plant4. Cellulose and hemicellulose represent abundant and inexpensive sources of fermentable sugar for the production of various chemicals and biofuels, but finding efficient catalysts for their saccharification to monomeric sugar and producing those catalysts in a cost-effective manner are major hurdles5.

Biological catalysts such as cellulase/hemicellulase enzymes play significant roles in the production of ethanol using plant biomass6. The enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose polymers is achieved by the synergistic activity of three different groups of cellulase enzymes1: endoglucanase2, exoglucanase or cellobiohydrolase, and3 β-glucosidase7,8. Arabinoxylanases and xylanases are groups of enzymes that hydrolyse hemicellulose components. A large number of these hydrolytic enzymes have been discovered in fungi9, but they are typically associated with certain limitations, such as stability to low pH and thermal stresses and low specific activities10. As bacteria are able to tolerate environmental extremes, they represent an ideal source for the screening and isolation of novel cellulolytic enzymes to help overcome these challenges10. Therefore, researchers are investigating natural systems that have evolved to decompose plant cell wall polymers as sources for enzyme discovery.

Arthropods are the most abundant and successful species on earth that can survive in diverse ecological niches11,12. The digestive tracts of arthropods contain microbiota members from the bacterial, fungal, protozoan and archaeal groups, which assist with various physiological functions including food digestion, nitrogen fixation, nutrition and pheromone production13. Comprehensive analyses of the transcriptomes and metagenomes of termites and symbiotic microbes have generated huge amounts of genomic information for the screening of cellulase encoding genes14,15. However, enzymes screened through metagenomic and metatranscriptomic studies could have issues with heterologous overexpression in terms of folding and yield16,17 because little is known about the host organism. Therefore, natural cellulolytic bacteria that can be cultured under laboratory conditions are excellent platforms for the study of the properties of hydrolytic enzymes.

In the present work, we have selected three arthropods with different dietary habits, i.e., two insects (termites and yellow stem-borers) and a crustacean (pill-bugs), and explored their guts as sources for the isolation and characterisation of cellulose-degrading bacteria. The ability of these arthropods to feed on wood, foliage and detritus is likely to involve catalysis by different types of cellulases/hemicellulases that are secreted by gut microbiota to digest the structural and recalcitrant lignocellulosic residues in their foods. Thus, the main goals of this study were to explore the guts of these arthropods that feed on potential biofuel feedstocks and to compare their hydrolytic activities. We successfully isolated 42 cellulose-degrading bacterial strains from these arthropods and characterised their abilities to produce hydrolytic enzymes.

Results

Screening and characterisation of cellulolytic bacteria from the guts of arthropods

The guts of arthropods feeding on woody and agricultural biomass are an ideal place for symbiotic cellulolytic microbes to thrive. We selected two insects, termites and yellow stem borers, and a crustacean, pill-bugs, because of their ability to live in diverse niches. Termites were collected from the trunks and roots of dead trees; pill-bugs were collected from dampened soil containing decomposed leaf litters; and yellow stem borers living in rice stems were collected from an agricultural rice field (Figure 1). Arthropod families were identified by performing BLAST with the nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (CO-I) genes from each organism and further confirmed by morphological characterisation. The nearest possible hits for termites, pill-bugs and yellow stem borers were Odontotermes hiananensis, Armadillidium sp. and Scirpophaga incertulas, respectively. The guts of these arthropods were dissected as described in the Methods section, and the microbes living in the guts were grown on agar plates containing CMC and trypan blue at various dilutions under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Unique isolated colonies showing clearance zones on a blue background were purified by re-streaking, and their cellulolytic capabilities were further confirmed by Congo red staining of agar plates18. Approximately 42 bacterial colonies were selected by the above screening method for phylogenetic analysis and enzymatic activity analysis. Among these, 26 bacteria were isolated by screening under aerobic conditions, and 16 were isolated under anaerobic conditions (Table 1).

Figure 1. Pictures of termites, pill-bugs and rice stem-borers collected from various ecological niches.

Table 1. Coding of cellulolytic microbes isolated from insect guts.

| Aerobic screening | Anaerobic screening | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insect | Strain ID | GenBank Accession | Nearest relative | Strain ID | GenBank Accession | Nearest relative |

| Termite | A1 | KC434960 | Bacillus sp. 6063 | T1 | KC434986 | Bacillus subtilis M50 |

| A4 | KC434961 | Klebsiella sp. clone F7 | T2 | KC434987 | Bacillus licheniformis ACO1 | |

| A5 | KC434962 | Trabulsiella guamensis GTC1379 | T3 | KC434988 | Trabulsiella guamensis GTC1379 | |

| A6 | KC434963 | Bacillus pumilus BSH4 | T4 | KC434989 | Bacillus sp. DV9-35 | |

| A7 | KC434964 | Bacillus sp. SCSSS10 | ||||

| A9 | KC434965 | Pantoea agglomerans WAB1927 | ||||

| A10 | KC434966 | Bacillus licheniformis EdyKolBl23 | ||||

| A11 | KC434967 | Bacillus licheniformis BCRC 15413 | ||||

| A12 | KC434968 | Bacillus licheniformis SubaMucBl16 | ||||

| A13 | KC434969 | Bacillus cereus TAUC5 | ||||

| A16 | KC434970 | Bacillus cereus F837/76 | ||||

| A17 | KC434971 | Bacillus subtilis K21 | ||||

| A18 | KC434972 | Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 36T | ||||

| Pill-Bug | A19 | KC434973 | Paenibacillus polymyxa YRL13 | W1 | KC434990 | Bacillus subtilis KL-073 |

| A21 | KC434974 | Bacillus subtilis M50 | W6 | KC434991 | Bacillus thuringiensis 2PR56-10 | |

| A22 | KC434975 | Bacillus subtilis M16K | W7 | KC434992 | Bacillus tequilensis VITJAAM2 | |

| A23 | KC434976 | Enterobacter aerogenes KCTC 2190 | ||||

| A24 | KC434977 | Cellulosimicrobium sp. TUT1242 | ||||

| Yellow Stem Borer | S1 | KC434978 | Bacillus species BB2_1A | U2 | KC434993 | Bacillus sp. PR 1.7 |

| S2 | KC434979 | Bacillus subtilis AQ1 | U3 | KC434994 | Pantoea species NCCP116 | |

| S3 | KC434980 | Microbacteriaceae bacterium HLB-6 | U4 | KC434995 | Pantoea agglomerans WAB1927 | |

| S4 | KC434981 | Microbacteriaceae bacterium BMC-3 | U5 | KC434996 | Klebsiella pneumoniae L-13 | |

| S5 | KC434982 | Microbacterium oleivorans CCGE2277 | U6 | KC434997 | Klebsiella pneumoniae L-13 | |

| S6 | KC434983 | Microbacterium arborescens DSM 20754 | U7 | KC434998 | Microbacteriaceae bacterium BMC-3 | |

| S7 | KC434984 | Microbacterium arborescens DSM 20754 | U8 | KC434999 | Bacillus subtilis C1Y001 | |

| S8 | KC434985 | Microbacterium arborescens JB8_2B | U9 | KC43500 | Enterobacter species DHM1T | |

| U10 | KC43501 | Serratia marcescens PS1 | ||||

Phylogenetic analysis of gut bacteria

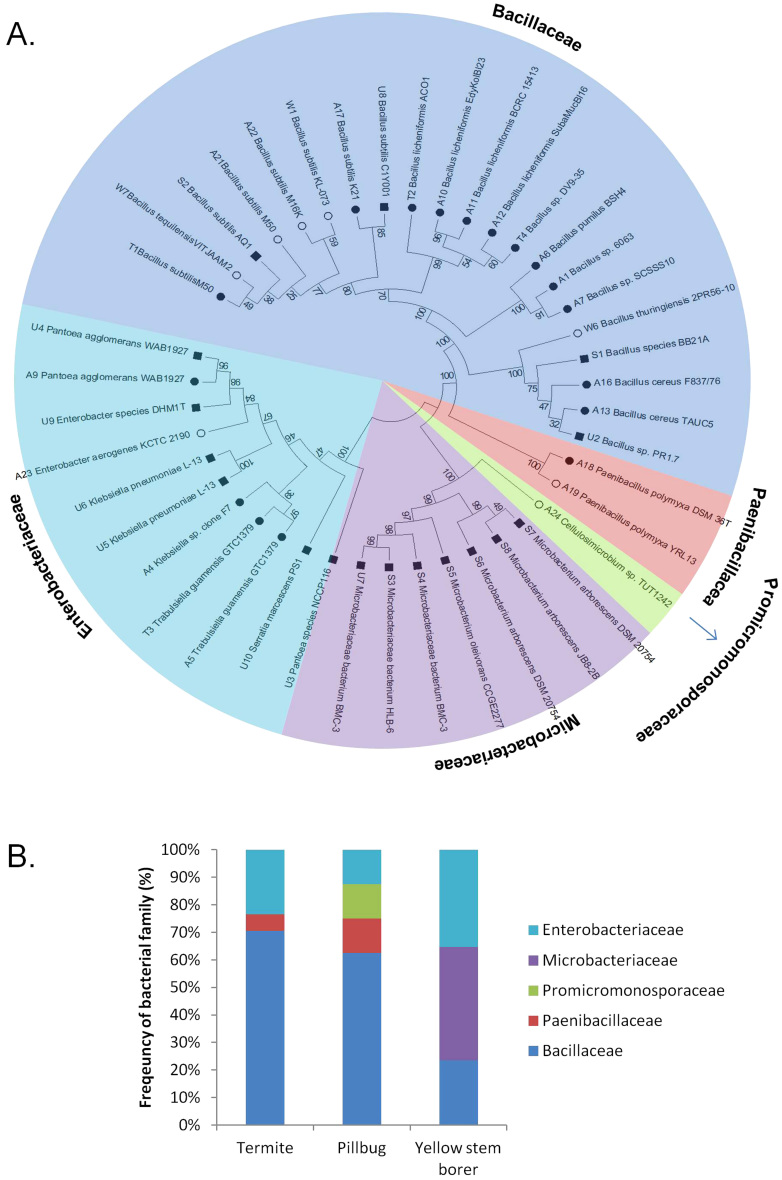

Among the 42 bacterial colonies selected for further characterisation, 17 were isolated from termite guts, 8 were isolated from pill-bug guts and 17 were isolated from yellow stem borer guts (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rDNA sequences revealed that all identified bacterial species belonged to five families - 50% belonged to Bacillaceae, 26% belonged to Enterobacteriaceae, 17% belonged to Microbacteriaceae, 5% belonged to Paenibacillaceae and 2% belonged to Promicromonosporaceae (Figure 2A). Between 60 and 70% of the bacteria from the guts of termites and pill-bugs were from the Bacillaceae family, while bacteria from the Microbacteriaceae and Enterobacteriaceae families were more dominant in the guts of yellow stem borers (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Classification and phylogenetic analysis of natural isolates from the guts of termites, pill-bugs and yellow stem-borers.

(A) 16s rDNA sequences of 42 isolates screened for their ability to produce cellulolytic enzymes obtained from the guts of termites ( ), pill bugs (

), pill bugs ( ) and yellow stem borers (

) and yellow stem borers ( ) were used to perform blast searches to identify their nearest neighbors, and MEGA5 was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The natural isolates were found to belong to five families. (B) Relative abundance of various bacterial families in the guts of these three arthropods.

) were used to perform blast searches to identify their nearest neighbors, and MEGA5 was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The natural isolates were found to belong to five families. (B) Relative abundance of various bacterial families in the guts of these three arthropods.

Characterisation of bacterial enzymes hydrolysing plant biomass

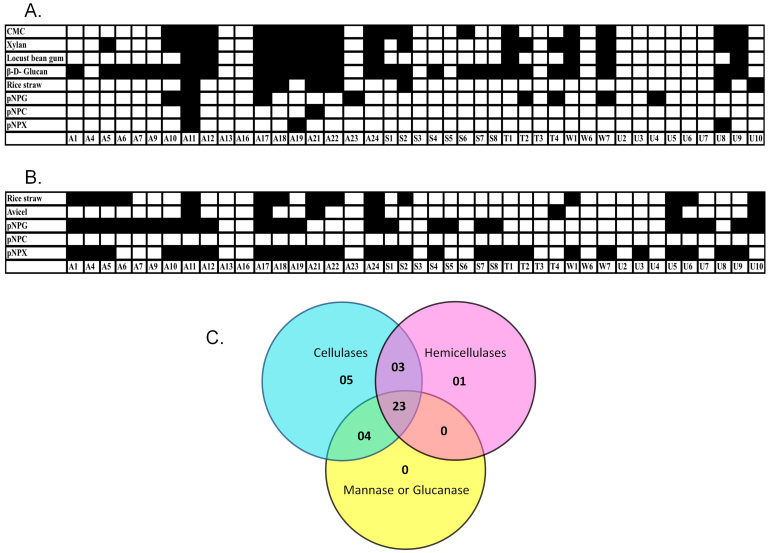

Microbes residing in the guts of biomass feeding arthropods are likely to produce a variety of hydrolytic enzymes. In previous studies we showed that Paenibacillus ICGEB2008 isolated from the gut of the cotton bollworm produced several biomass-degrading enzymes, including cellulases and hemicellulases18,19. Therefore, we tested the expression levels in the gut microbes of major glycosyl hydrolase enzymes belonging to the categories of cellulase, hemicellulase, mannanase and glucanase. The expression levels of endoglucanase, β-glucosidase, xylanase, β-xylosidase, mannanase and β-D-glucanase were determined using the substrates CMC, pNPG, Xylan, pNPX, locust bean gum and barley β-D-glucan, respectively. To test exocellulase or cellobiohydrolase expression, both Avicel and pNPC (in the presence of the β-glucosidase inhibitor glucono-δ-lactone) were used as substrates. A potential biofuel feedstock was also used, namely alkali treated rice straw, and it mainly contained crystalline cellulose as well as some amorphous forms of cellulose. These assays were used to test both extracellular and cell associated enzymes. Except for A13, A16 and T3, all natural isolates produced at least one type of glycosyl hydrolase (Figure 3A and 3B). The reason that these three strains are negative in the liquid assay despite being positive for CMC activity on the agar plates could be related to the stringency criteria set as described in the Methods section. The majority of microbes produced more than one kind of hydrolytic enzyme (Figure 3C). There were 23 microbes that produced at least one hydrolytic enzyme from each category of biomass degrading enzymes. Several strains produced only one category of enzyme, such as cellulases (5 strains) and hemicellulases (1 strain), which hydrolysed pNPG and pNPX, respectively, but did not produce significant amounts of any other type of hydrolase (Figure 3). Extracellular fractions were found to be rich in enzymes specific for amorphous polymers (Figure 3A). Only a few microbes secreted enzymes that were able to hydrolyse dimeric or oligomeric substrates, such as pNPG, pNPC and pNPX, or complex structures, such as rice straw. On the other hand, the majority of cell associated fractions hydrolysed dimeric substrates such as pNPG and pNPX (Figure 3B). However, cell associated fractions of none of the microbes were able to hydrolyse pNPC. Some strains also produced enzymes in the extracellular or cell-associated fractions for the hydrolysis of complex structures such as rice straw and Avicel.

Figure 3. Qualitative assessment of hydrolytic enzymes produced by various natural isolates.

Enzyme production was tested in the extracellular (A) and cell-bound fractions (B) against amorphous, crystalline and chromogenic substrates. Black and white boxes represent significant and non-significant activities, respectively, in the liquid culture assay. (C) Venn diagram for natural isolates exhibiting cellulase, hemicellulase and other glycosidase activities. Cellulase positive strains were considered to be those that hydrolysed CMC, Avicel, rice straw, pNPC or pNPG. Hemicellulase positive strains were those that hydrolysed xylan or pNPX. Strains that hydrolysed locust bean gum or β-D-glucan were considered to be positive for other glycosyl hydrolases.

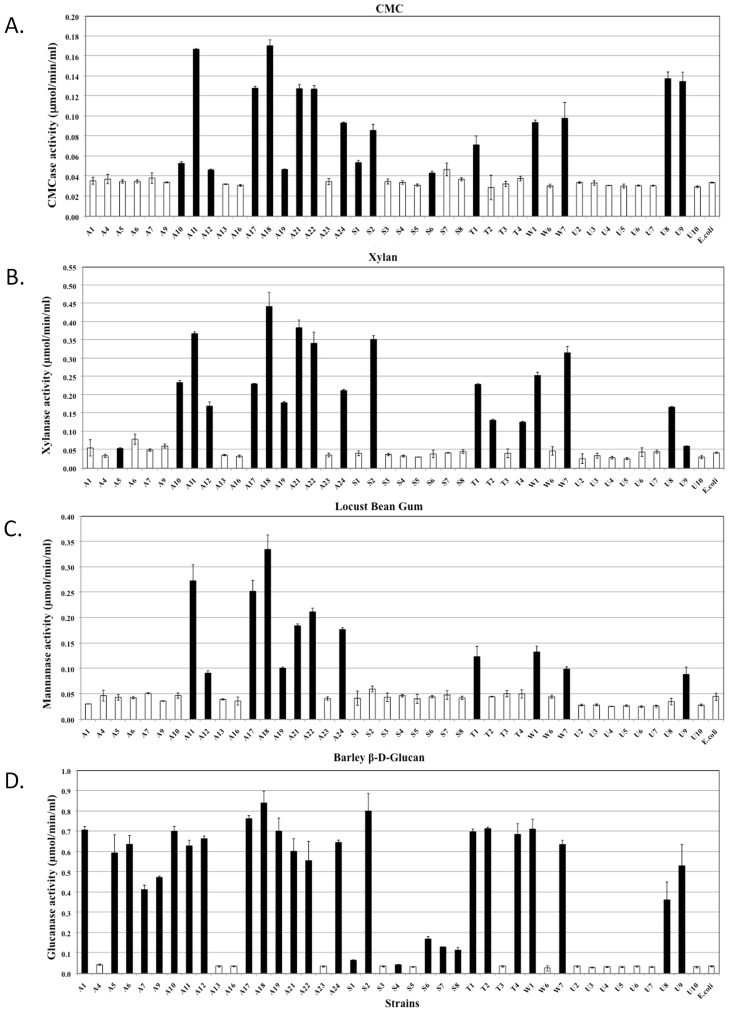

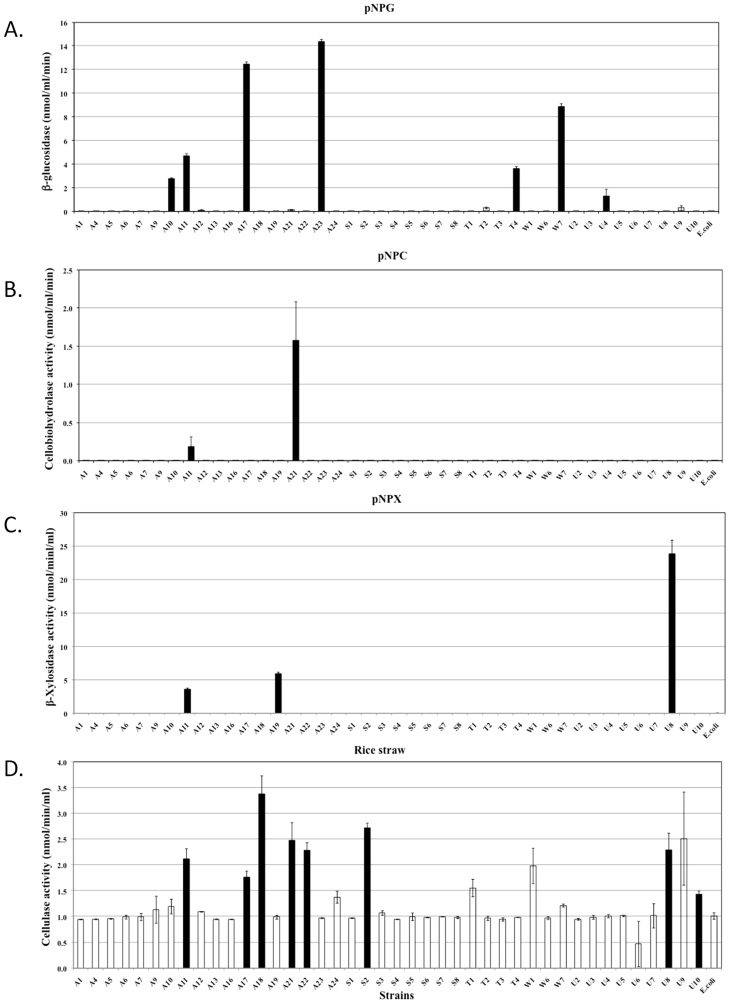

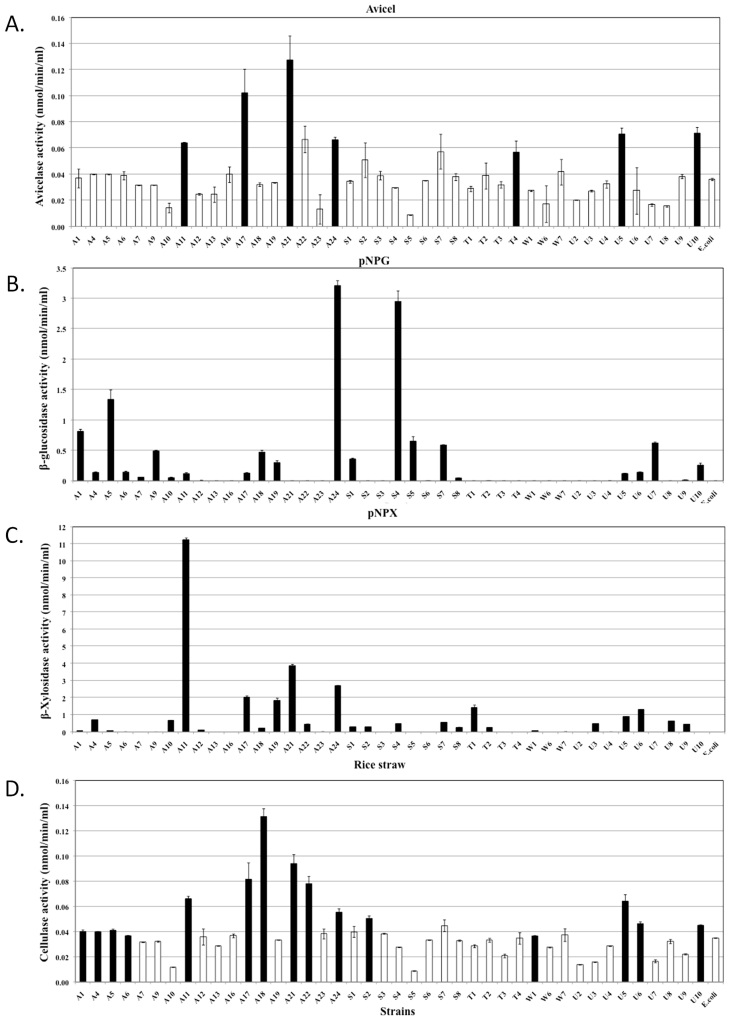

Quantitative assessments of the hydrolytic activities in both the extracellular and cell-associated fractions enabled us to analyse their relative contributions to biomass degradation (Figure 4, 5 and 6). The majority of strains secreted high quantities of enzymes specific for amorphous polymers such as CMC, xylan, locust bean gum and barley β-D-glucan (Figure 4). Relatively fewer strains produced enzymes that were able to hydrolyse significant amounts of crystalline polymers such as Avicel and rice straw (Figure 5D, 6A and 6D). The strains hydrolysing the greatest amounts of rice straw were A11, A18, A21, A22, S2 and U8 (Figure 5D and 6D), while strains A11, A17, A21, A24, U5 and U10 hydrolysed Avicel (Figure 6A). Enzymes secreted from strains A11 and A21 also hydrolysed pNPC, indicating that these strains might produce either cellobiohydrolase or processive endoglucanase (Figure 5B). None of the cell bound fractions from any of the strains hydrolysed pNPC. Among β-glucosidase producers, a distinct set of strains exhibited extracellular and cell-associated β-glucosidase activity (Figure 5A and Figure 6B). Only three strains, A11, A19 and U8, produced extracellular β-xylosidase (Figure 5C). The remaining xylosidase producers expressed the β-xylosidase enzyme intracellularly (Figure 6C).

Figure 4. Quantitative assessment of the enzymatic activities of extracellular fractions against amorphous polysaccharides.

All bacterial strains that were found to be cellulase positive by the agar plate assay were grown in liquid medium, and their extracellular fractions were tested for the hydrolysis of various substrates. Each graph indicates the substrate. Black bars represent strains that exhibited significantly higher activities compared to the negative controls, while white bars represent negative strains. The data represent the average and standard deviation of two different assays.

Figure 5. Quantitative assessment of the enzymatic activities of extracellular fractions against chromomeric substrates and rice straw.

All bacterial strains that were found to be cellulase positive by the agar plate assay were grown in liquid medium, and their extracellular fractions were tested for the hydrolysis of various substrates. Each graph indicates the substrate. Black bars represent strains that exhibited significantly higher activities compared to the negative controls, while white bars represent negative strains. The data represent the average and standard deviation of two different assays.

Figure 6. Quantitative assessment of the enzymatic activities of the cell-bound fractions.

All bacterial strains that were found to be cellulase positive by the agar plate assay were grown in liquid medium, the cells were lysed by sonication, and the lysed cell samples were tested for the hydrolysis of various substrates. Each graph indicates the substrate. Black bars represent strains that exhibited significantly higher activities compared to the negative controls, while white bars represent negative strains. The data represent the average and standard deviation of two different assays.

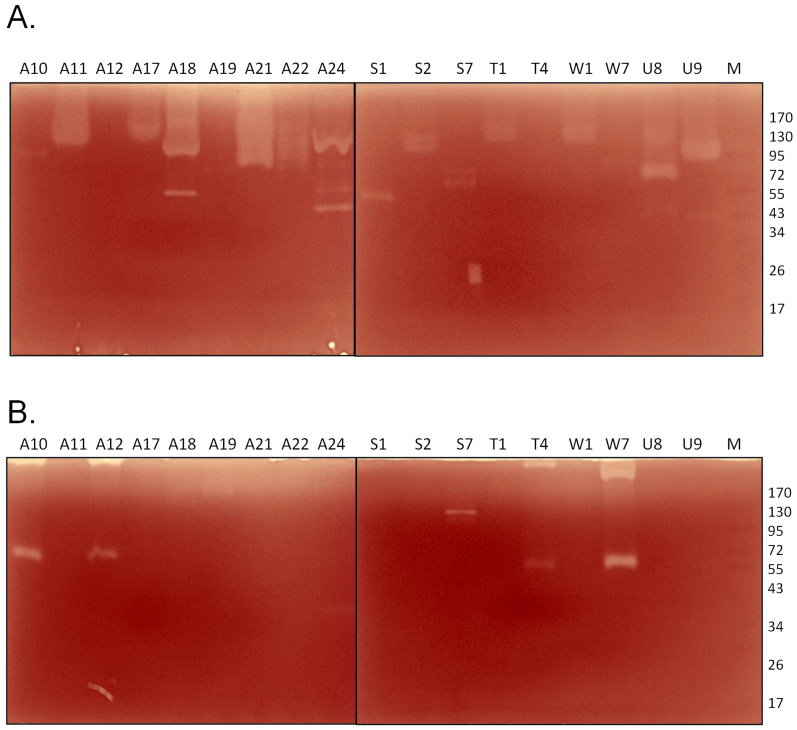

Cellulase and hemicellulase production were further evaluated using a zymogram. We selected 18 strains from the CMC positive batch and tested the extracellular enzymatic activity by a zymogram. The strains that secreted high quantities of cellulase, A11, A17, A18, A21, A22, U8 and U9 (Figure 4A), also showed significant clearance zones on the zymogram (Figure 7A). Most of the strains secreted cellulases in the range of 72–130 kDa, and a few secreted cellulases in the range of 43–53 kDa. The zymogram results were somewhat ambiguous for xylanase activity. Although 16 of the 18 strains tested by zymogram exhibited significant xylanase activity in the liquid culture assay (Figure 4B), only 5 strains showed xylanolytic activity on the zymogram (Figure 7B). The samples of these 5 strains contained high molecular weight bands, possibly protein oligomers, that could not be resolved by the gel. Similar problems might have occurred with other xylanase positive strains, thus preventing the detection of activity by the zymogram. Four strains, A10, A12, T4 and W7, exhibited xylanase activity at ~55 kDa, while strain S7 exhibited xylanase activity at ~100 kDa (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Zymograms to determine the enzymatic activities of the extracellular fractions of natural isolates against (A) CMC and (B) xylan.

Kinetic properties of pNPC hydrolysing cellulases

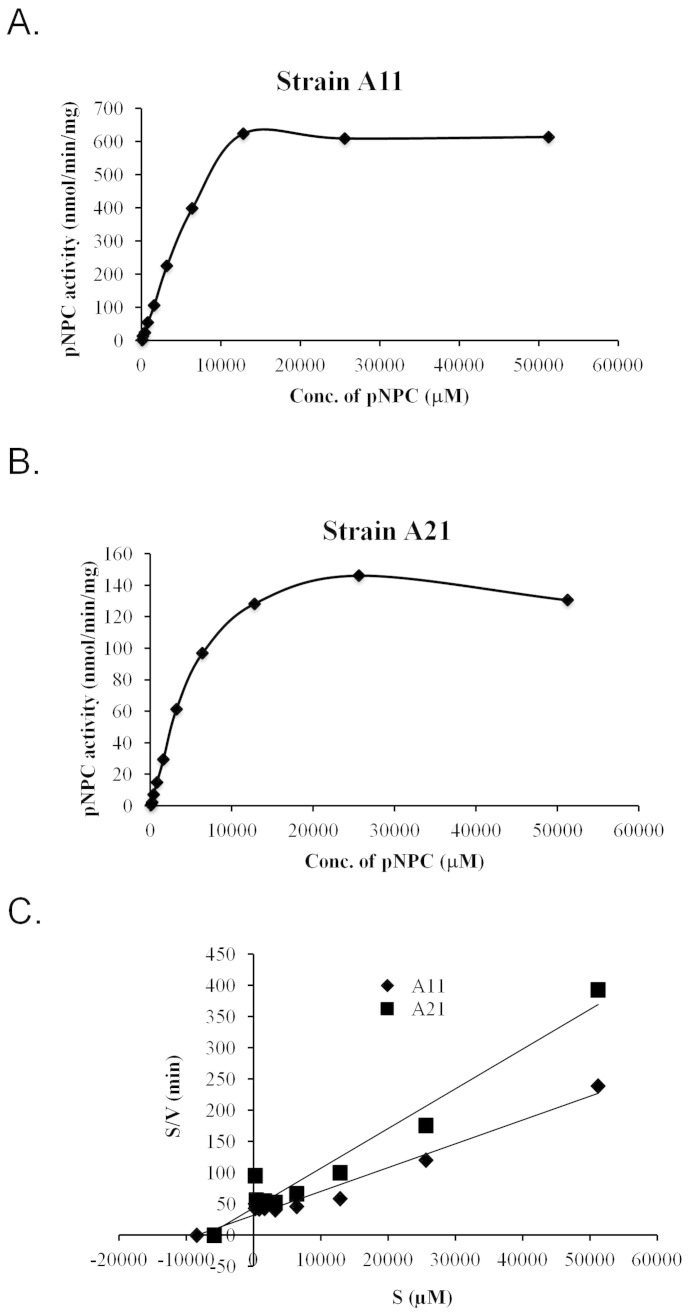

Two strains, A11 and A21, displayed enzymatic activities against pNPC, indicating that they were secreting either cellobiohydrolase or processive endoglucanase. Therefore, we further characterised the enzymes present in these strains by partially purifying extracellular fractions via ultrafiltration using a 10-kDa cut-off membrane and then using that preparation to analyse their kinetic properties. The enzyme prepared in this way from the A11 strain exhibited a 4-fold higher activity at the saturating substrate concentration compared to the A21 strain (Figure 8A and 8B). The Km and Vmax values calculated from the Hanes Woolf plot (Figure 8C) were 8.47 mM and 263 nmol/min for A11, respectively, and 7.06 mM and 158 nmol/min for A21, respectively. These parameters suggest that although the enzyme preparations from both microbes exhibit similar substrate affinities, the enzyme preparation from A11 has a 1.7 times higher catalytic efficiency than A21.

Figure 8. Kinetic properties of enzyme preparations from strains A11 and A21.

Substrate (para-nitrophenyl cellobiose (pNPC)) saturation kinetics of the (A) A11 and (B) A21 strains. (C) Hanes-Woolf graph for the calculation of Km and Vmax. The data represent the average of two different assays.

Discussion

Finding optimal enzymes for biomass hydrolysis remains a challenge for scientists developing methods of lignocellulosic ethanol production. Nature has created reservoirs of catalysts that perform this function in a variety of niches. We have attempted to mine these biological reservoirs by selecting arthropods from three diverse niches and screening for microbes capable of biomass hydrolysis in their guts. While other methodologies such as metagenomics and metatranscriptomics are becoming popular approaches to screen for biomass hydrolysing enzymes, they are often associated with issues of low heterologous expression yield and protein misfolding16. Our approach of identifying culturable microbes with biomass hydrolysing capabilities has the advantage of studying the enzyme characteristics in both homologous and heterologous hosts.

This study has revealed significant knowledge regarding the diversity of microbes existing in the guts of arthropods and their roles in biomass degradation. Among the arthropods we selected for this study, termites are the best-studied arthropods in terms of cellulolytic microbes13,14,15, although the majority of the cellulolytic microbes that have been identified are difficult to culture in the lab. No previous studies have reported on the nature of cellulolytic microbes existing in the guts of pill-bugs and yellow stem borers. We found that greater than 60% of the cellulolytic microbes isolated from the guts of termites and pill-bugs belonged to the Bacillaceae family, while greater than 75% of the cellulolytic microbes isolated from the guts of yellow stem borers belonged to the Microbacteriaceae and Enterobacteriaceae families. These differences in the microbial flora reflected differences in the food habits of the arthropods. While termites and pill-bugs were collected from decomposed trees and litter, yellow stem borer larvae were collected from rice plants at the time of seeding. The pill-bug gut also contained Cellulosimicrobium sp., a known natural producer of cellulases and xylanases.

Hydrolytic enzymes have been reported in both the extracellular and cell-bound fractions18,19,20,21. More often, the enzymes hydrolysing amorphous polysaccharides are secreted, while those hydrolysing crystalline substrates are found in the membrane-bound fraction of the bacteria18,20. Enzymes hydrolysing dimeric sugars into monomeric forms can be found in both fractions19,22. Therefore, we selected substrates to analyse the hydrolysing enzymes present in both the extracellular and cell-bound fractions. The majority of the natural isolates were expected to produce CMCases as they were selected on CMC containing agar plates. Among a total of 42 selected strains, 17 secreted significant amounts of endocellulase. The remaining strains did not pass the stringency criteria of the liquid assay. Most of the CMCase producing strains also secreted hydrolytic enzymes for other amorphous substrates. We found a large number of strains producing cell-bound enzymes to hydrolyse dimeric substrates, although few strains also secreted these enzymes into the extracellular medium. Few strains demonstrated significant Avicelase activity in the cell-bound fraction or pNPC activity in the extracellular fraction, indicating the presence of hydrolytic enzymes against crystalline substrates.

Enzyme production by the major CMCase and xylanase producers was further confirmed by performing zymograms. A number of enzymes have been reported in the literature with CMCase activity in the ranges of 40 kDa and 90 kDa and xylanase activity in the range of 60 kDa18,23,24. The xylanase activity with a much higher molecular mass is intriguing and could represent oligomers.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide insight into the presence of diverse microbial flora in the guts of three arthropods differing in their food habits and into the roles of these floras in the degradation of plant biomass. The knowledge gained from these studies could be exploited for the identification of novel enzymes and the development of enzyme systems for the effective hydrolysis of plant biomass.

Methods

Media composition and chemical reagents

Tryptic Soya broth (1.7% Tryptone, 0.3% Soya peptone, 0.25% K2HPO4 and 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.0) (Sigma, USA) was used as the medium for the cultivation of microbes in liquid culture and on agar Petri-plates. Reagents for analytical assays such as cellobiose, Avicel, birchwood xylan, carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), p-nitrophenyl β-D-cellobioside (pNPC), p-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) and p-nitrophenyl β-D-xylopyranoside (pNPX) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Alkali-treated rice straw was obtained from ICT, Mumbai25.

Collection of host organisms

Approximately 25 wood-feeding worker termites and litter-feeding pill bugs were collected from different locations of ICGEB, New Delhi, India, and 25 yellow stem-borer insect larvae were collected from the paddy fields of the Biotechnological Research Experiments field, Raipur University, Chhattisgarh, India during the month of October, 2011. The guts of the insects were processed to isolate microbes, and host DNA was isolated from the carcasses for species identification.

Screening for cellulase producing bacteria

To isolate gut microbes, the insects were first pre-chilled on ice for 2–3 min, followed by surface sterilisation with 70% ethanol for 1 min. All the dissections were performed in the laminar flow cabinet. Guts were carefully removed with the help of aseptic needles and placed in a 1.5 ml sterile microfuge tube containing 100 μl of ice-cold buffered saline solution (pH 7.2)18. The guts were then homogenised using a micropestle, and the suspension was serially diluted from 10−1 to 10−7, plated on Tryptic Soya agar (TSA) plates containing 0.5% CMC and 0.1% trypan blue, and incubated for 72 h at 30°C. Isolated bacterial colonies showing clearance zones on the plates were further confirmed to produce cellulase by spreading on a TSA-CMC plate and observing the clearance zone via the Congo-red method18, and the results of this experiment were then used to select colonies for further characterisation. To isolate anaerobic bacteria, all dissections and platings were performed under anaerobic conditions in an anaerobic chamber (Shel Lab).

Identification of microbial and arthropod families

All the bacterial strains showing clearance zones were streaked onto TSA plates and sent to Macrogen for 16S rDNA sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis was performed based on the blast results of the 16S rDNA sequence. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method26. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter method27, and evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA528.

The host species were identified using the molecular marker gene mitochondrial CO-I based on the previously described method29. Genomic DNA from the host organisms was isolated by the conventional hexadecyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB) method30, and the universal DNA primers LCO1490 (5′-ggtcaacaaatcataaagatattgg-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-taaacttcagggtgaccaaaaaatca-3′) were used to amplify the 710-bp region of the mitochondrial CO-I gene. The PCR product was analysed on a 1% agarose gel in the presence of ethidium bromide, purified using a gel extraction kit (Genetix) and sent to Macrogen for sequencing. The nucleotide sequences were then used in a Blast search to identify the arthropod families. The arthropod families were further confirmed by morphological identification31,32.

Cultivation of microbes under laboratory conditions

Microbial strains isolated from the guts of insects were grown in Tryptic soya broth medium supplemented with 1% alkali pretreated rice straw at 37 °C at 150 rpm for 48 h. To grow natural isolates under anaerobic conditions, the cultures were grown at 37 °C for 72 h in anaerobic chambers. After the cell growth reached the stationary phase, the culture broth was centrifuged at 8000 × g for 20 min, and then the supernatant was used as the source of extracellular enzymes. The cells were re-suspended in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and lysed either by sonication in the case of aerobically grown cultures or by glass beads inside the anaerobic chamber in the case of anaerobically grown cultures. The resulting crude lysate was used as the cell-bound fraction.

Assays for enzymatic activity

The enzymatic activities of endocellulase (β-1,4-endoglucanase), cellobiohydrolase (β-1,4-exoglucanase), glucosidase (β-1,4-glucosidase), xylanase (β-1,4-endoxylanase), xylosidase (β-1,4-xylosidase), glucanase (β-D-glucanase) and mannanase (β-1,4-mannanase) were assayed using CMC, Avicel and pNPC, pNPG, birchwood xylan, pNPX, barley β-D-glucan and locust bean gum, respectively. Alkali pre-treated rice straw was also used as a substrate, as it was a potential feedstock for biofuel generation. The enzymatic activities in the supernatant were tested for their ability to hydrolyse CMC, pNPC, pNPG, xylan, pNPX, glucan, locust bean gum and rice straw. The enzymatic activities in the cell lysate were measured based on their activity against Avicel, pNPC, pNPG, pNPX and rice straw.

The reducing sugar released upon the hydrolysis of sugar polymers was measured by the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) method, and the para-nitrophenol released upon the hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate was measured by monitoring the absorbance at 405 nm19,27. Briefly, a crude enzyme solution (0.125 ml) was mixed with 0.125 ml of a 1% sugar polymer solution in 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. Enzymatic reactions containing Avicel and rice straw as substrates were incubated for 60 min. The reducing sugar produced in these experiments was measured by the DNS reagent at 540 nm18. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of reducing sugar from the substrate per minute under the above conditions.

For enzymatic assays with chromogenic substrates, 0.125 ml of enzyme sample was mixed with 0.55 ml of 5 mM substrate in 50 mM citrate phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and incubated at 50°C for 30 min. The enzyme assay with pNPC substrate was set up in the presence of 100 mM glucono-δ-lactone, an inhibitor of β-glucosidase activity, in a 0.2 ml volume. The reaction was stopped after incubation by the addition of 1 ml of 2 M Na2CO3, and the absorbance of the released p-nitrophenol was measured at 405 nm. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme catalysing the release of 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol per minute under the above conditions19.

All assays were performed in duplicate, and the data presented here represent the average of the two readings. E. coli DH5α grown under similar conditions was taken as a negative control for all of the enzymatic assays. The data obtained for the experimental conditions and negative controls were compared in multiple comparisons using Student's t-test. The statistical significance of differences between various test samples and the control sample were determined using two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The kinetic parameters of enzymes produced by strains A11 and A21 against pNPC were determined as follows. The strains were grown in 1 L of TSB medium and harvested to obtain the extracellular fractions. The extracellular fractions were concentrated 50-fold using a 10 kDa cut-off poly-ether-sulphone membrane in a Labscale XL system (Merck Millipore) and buffer exchanged. This partially purified enzyme preparation was used for enzyme assays with different concentrations of pNPC ranging from 100 μM to 5120 μM. The substrate affinity (Km) and catalytic efficiency (Vmax) of these enzyme preparations were calculated using the Hanes-Woolf linear transformation33.

Analytical methods

To assess the CMCase or xylanase activity of the protein by zymograms, the samples were resolved on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel containing either 0.5% (wt/vol) CMC or 0.5% (wt/vol) xylan. After electrophoresis, the gel was washed once with 20% (vol/vol) isopropanol in PBS for 1 min followed by three washes of 20 min each in PBS. The gel was incubated in PBS at 37°C for 1 h, stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) Congo red for 30 min, and destained with 1 M NaCl. Clear bands against the red background indicated CMCase or xylanase activity. Protein concentrations were estimated with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences of 16S rDNA obtained in this study have been deposited in the NCBI gene bank, and the GenBank accession numbers of the bacterial isolates are listed in Table 1.

Author Contributions

S.S.Y., R.B. and N.A. designed the experiments; Z.B., V.K.K., N.A. and G.C. collected the arthropods; Z.B., V.K.K., N.A. and A.S. conducted the experiments; Z.B. and S.S.Y. performed the computational analysis and prepared the figures; Z.B., V.K.K. and S.S.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Arvind Lali for providing us alkali pretreated rice straw. We acknowledge financial support from the Department of Biotechnology of the Government of India.

References

- Himmel M. E. & Bayer E. A. Lignocellulose conversion to biofuels: current challenges, global perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 316–317 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G. & Buchs J. Biocatalytic conversion of lignocellulose to platform chemicals. Biotechnol. J. 7, 1122–1136 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard R. L., Abotsi E., Jansen van Rensburg E. L. & Howard S. Lignocellulose biotechnology: issues of bioconversion and enzyme production. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2, 602–619 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Lange J. P. Lignocellulose conversion: an introduction to chemistry, process and economics. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 1, 39–48 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Stephanopoulos G. Challenges in engineering microbes for biofuels production. Science 315, 801–804 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beguin P. & Aubert J. P. The biological degradation of cellulose. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 13, 25–58 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M. K. & Bhat S. Cellulose degrading enzymes and their potential industrial applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 15, 583–620 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashtban M., Maki M., Leung K. T., Mao C. & Qin W. Cellulase activities in biomass conversion: measurement methods and comparison. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 30, 302–309 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashtban M., Schraft H. & Qin W. Fungal bioconversion of lignocellulosic residues; opportunities & perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5, 578–595 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki M., Leung K. T. & Qin W. The prospects of cellulase-producing bacteria for the bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5, 500–516 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May R. M. The dimensions of life on earth. Nature and Human. Society: the Quest for a Sustainable World (ed. by Raven, P. H. & Williams, T.), pp. 30–45 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. How insects lose their limbs. Nature 415, 848–849 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongoh Y. Diversity and genomes of uncultured microbial symbionts in the termite gut. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74, 1145–1151 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke F. et al. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450, 560–565 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartar A. et al. Parallel metatranscriptome analyses of host and symbiont gene expression in the gut of the termite Reticulitermes flavipes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2, 25 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lorenzo V. Problems with metagenomic screening. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1045 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T. & Miyazaki K. Functional metagenomics for enzyme discovery: challenges to efficient screening. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 616–622 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlakha N., Rajagopal R., Kumar S., Reddy V. S. & Yazdani S. S. Synthesis and characterization of chimeric proteins based on cellulase and xylanase from an insect gut bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4859–4866 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlakha N., Sawant S., Anil A., Lali A. & Yazdani S. S. Specific fusion of β-1,4-endoglucanase and β-1,4-glucosidase enhances cellulolytic activity and helps in channeling of intermediates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7447–7454 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes C. M. & Gilbert H. J. Cellulosomes: highly efficient nanomachines designed to deconstruct plant cell wall complex carbohydrates. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 655–681 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood T. M., Wilson C. A. & Stewart C. S. Preparation of the cellulase from the cellulolytic anaerobic rumen bacterium Ruminococcus albus and its release from the bacterial cell wall. Biochem. J. 205, 129–137 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Zhang J., Zou G., Wang C. & Zhou Z. Improvement of cellulase activity in Trichoderma reesei by heterologous expression of a beta-glucosidase gene from Penicillium decumbens. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 49, 366–371 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleman-Leyer K. M., Siika-Aho M., Teeri T. T. & Kirk T. K. The Cellulases Endoglucanase I and Cellobiohydrolase II of Trichoderma reesei Act Synergistically To Solubilize Native Cotton Cellulose but Not To Decrease Its Molecular Size. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 2883–2887 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. K. & Zeikus J. G. Purification and characterization of an endoglucanase (1,4-beta-D-glucan glucanohydrolase) from Clostridium thermocellum. Biochem. J. 199, 341–350 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lali A. M. et al. Method for preparation of fermentable sugars from biomass. patent application PCT/IN2010/000355 (2010).

- Saitou N. & Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–20 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R. & Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F. M. et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York City, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Brusca R. C., Coelho V. & Taiti S. A guide to the coastal Isopods of California. Internet address: http://tolweb.org/notes/?note_id=3004.x (2001).

- Roonwal M. L. & Chhotani O. B. Termite fauna of Assam region, Eastern India. Proc. Natn. Inst. Sci. India 28, 282–406 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Segel I. H. Biochemical Calculations: How to Solve Mathematical Problems in General Biochemistry, 2nd edn. New York: John Wiley (1976). [Google Scholar]