Abstract

The triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins trienomycins A and F are prepared in 16 steps (longest linear sequence, LLS) and 28 total steps. The C11-C13 stereotriad is prepared via enantioselective ruthenium catalyzed alcohol CH-syn-crotylation followed by chelation-controlled carbonyl dienylation. Enantioselective rhodium catalyzed acetylene-aldehyde reductive coupling mediated by gaseous hydrogen forms a diene that ultimately is subjected to diene-diene ring closing metathesis to form the macrocycle. The present approach is 14 steps shorter (LLS) than the prior syntheses of trienomycins A and F, and 8 steps shorter (LLS) than any prior synthesis of a triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycin.

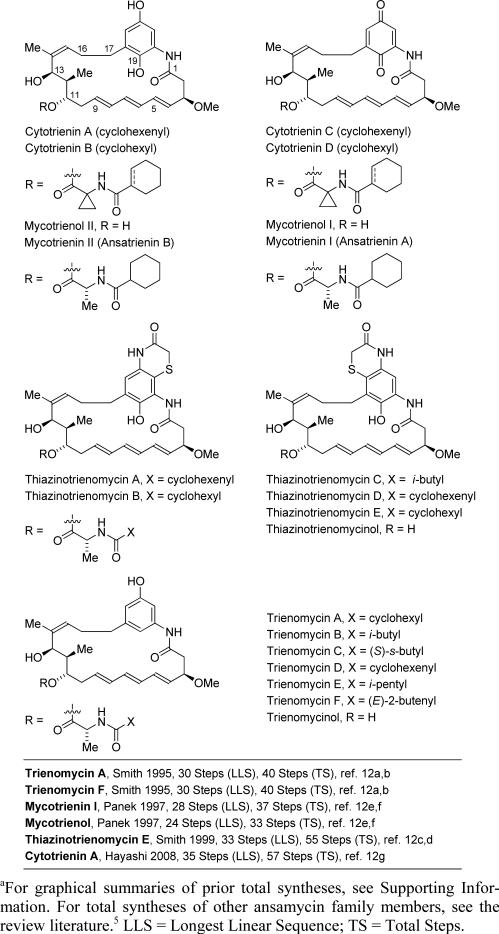

Roughly 20% of the top-selling small molecule drugs are polyketides derived from soil bacteria,1,2 and it is estimated that polyketides are five times more likely to possess drug activity compared to other classes of natural products.3 Despite the significance of polyketides, less than 5% of the soil bacteria from which they derive are amenable to culture.4 Hence, as methods for bacterial culture improve, it is anticipated that polyketides will become even more important to human medicine. Among polyketides, the ansamycins have emerged as important antibiotic and antineoplastic agents.5 The first ansamycins, the rifamycins, were discovered in the late 1950's in soil samples taken from the south of France.6 These compounds were largely responsible for vanquishing drug-resistant tuberculosis in the 1960's and were forerunners to what is now a broad class of medicinally relevant compounds.5 An important ansamycin subclass are the triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins or “ansatrienins.”7-9 This subclass emanates from different Streptomyces and Bacillus species and encompasses the mycotrienins/mycotrienols,7 the trienomycins,8 and the cytotrienins (Figure 1).9 While the mycotrienins display anti-fungal properties,7d,e the trienomycins and cytotrienins exhibit antineoplastic activity.8a,10 Elegant studies conducted in the Smith laboratory led to the stereochemical assignment of the trienomycins and mycotrienins,11 as well as total syntheses of trienomycins A and F and thiazinotrienomycin E.12a-c Subsequently, Panek reported total syntheses of mycotrienol I and mycotrienin I,12d,e and Hayashi reported a total synthesis of cytotrienin A.12g Syntheses of the ansatrienol and cytotrienin cores were reported by Kirschning13a and Panek,13b as well as our own laboratory.13c Here, using hydrogen mediated C-C couplings developed in our laboratory,14 we report the total synthesis of the triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins, trienomycins A and F. The present approach represents the most concise route to any triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycin.

Figure 1.

Triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins and prior total syntheses.a

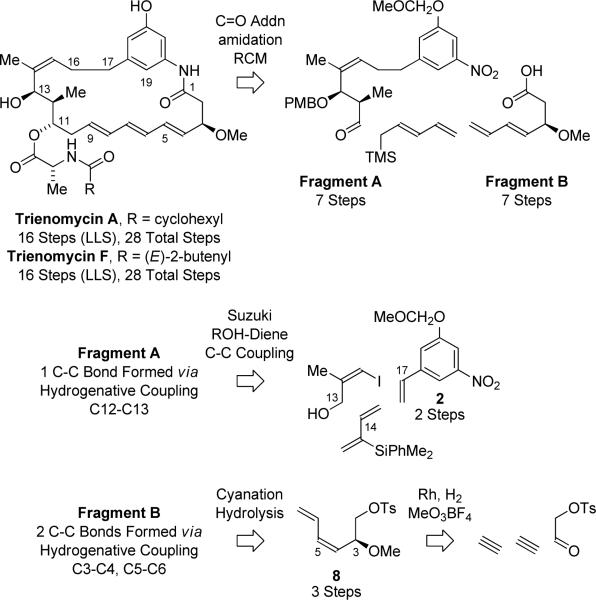

Our retrosynthetic analysis of trienomycins A and F invokes a convergent assembly of Fragments A and B wherein (E)-trimethyl-2,4-pentadienylsilane15 serves as a linchpin through chelation controlled aldehyde addition16 followed by diene-diene ring closing metathesis (RCM) (Scheme 1).13b Fragment A is itself prepared using an enantio- and syn-diastereoselective ruthenium catalyzed crotylation developed in our laboratory,17a which enables direct C-C coupling of a (Z)-configured trisubstituted allylic alcohol obtained via Suzuki reaction of (Z)-3-iodo-2-methyl-1-propenol and the indicated vinylarene 2. Fragment B is prepared in accordance with our previously described procedure involving the C-C bond forming hydrogenation of acetylene in the presence of the p-toluenesulfonate of hydroxy acetaldehyde.13c,18 The present syntheses of trienomycins A and F overcomes limitations evident in our prior work on the cytotrienin core pertaining to formation of the C11-C13 stereotriad, introduction of the side chain at C11, and late stage protecting group cleavage.13c

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins trienomycins A and F.

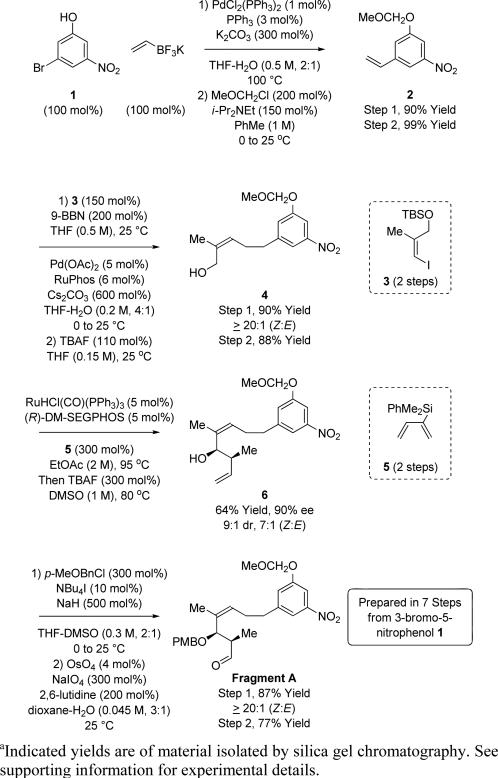

The synthesis of Fragment A begins with successive Suzuki cross-coupling to form the C17-C18 and C15-C16 bonds, respectively (Scheme 2). First, Suzuki-Molander coupling of 3-bromo-5-nitrophenol 1 with potassium ethenyltrifluorobo-rate19 provides, after MOM-protection, vinylarene 2. Second, in a one-pot procedure, regioselective hydroboration of vinylarene 2 using 9-BBN followed by B-alkyl Suzuki cross-coupling20,21 with (Z)-3-iodo-2-methyl-1-propenol TBS ether 322 provides the (Z)-allylic alcohol 4 as a single olefin stereoisomer. Direct redox-triggered syn-crotylation of the (Z)-allylic alcohol 4 using silyl-substituted diene 5 as a crotyl donor17a enables enantio- and diastereoselective formation of homoallylic alcohol 6. Protection of the C13 alcohol as the PMB ether followed by oxidative cleavage of the terminal olefin using a modification of the Johnson-Lemieux protocol23 provides the aldehyde Fragment A in only 7 steps from the phenol 1.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Fragment A via ruthenium catalyzed syn-crotylation employing silyl substituted diene 5.a

The carboxylic acid, Fragment B, previously was prepared in 12 steps in 16% overall yield.12g Our approach to Fragment B is accomplished in 7 steps from allyl alcohol in 32% overall yield.13c The synthesis begins with the enantioselective hydrogen-mediated C-C coupling of acetylene to the acetalde-hyde derivative 7 to form the product of (Z)-butadienylation,18 which upon treatment with Meerwein's reagent provides the methyl ether 8. Palladium catalyzed diene isomerization24 followed by substitution of the p-toluenesulfonate by cyanide and, finally, peroxide assisted hydrolysis of the resulting nitrile delivers Fragment B. A remarkable feature of this sequence relates to the ability to engage aldehyde 7 in carbonyl (Z)-butadienylation without inducing epoxide formation through displacement of the vicinal p-toluenesulfonate (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Fragment B via rhodium catalyzed reductive C-C coupling of acetylene.a

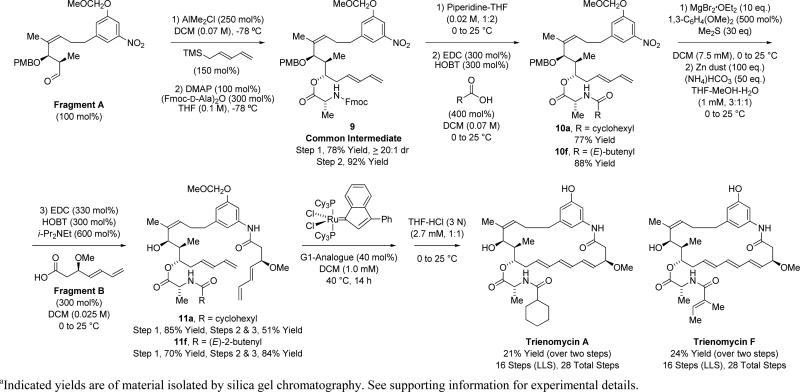

To complete the syntheses of trienomycins A and F, Fragment A is exposed to (E)-trimethyl-2,4-pentadienylsilane15 in the presence of AlMe2Cl to generate the product of chelation-controlled pentadienylation,16 followed by acylation with the symmetrical anhydride of N-Fmoc-D-alanine to provide 9 (Scheme 4). It was found that the major syn-diastereomer of Fragment A reacts more quickly than the corresponding anti-diastereomer, allowing the stereotriad of compound 9 to form as a single isomer as determined by 1H NMR analysis.25 By introducing different acyl moieties at C11, compound 9 serves as a common intermediate in the syntheses of trienomycins A and F and potentially other triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins. Treatment of compound 9 with piperidine, followed by the indicated acids permits formation of amides 10a and 10f. Cleavage of the PMB ethers26 of 10a and 10f in the presence of the 1,3-diene moieties required special conditions. Subsequent reduction of the C20 nitro moieties and acylation of the resulting anilines with Fragment B provides the tetraenes 11a and 11f, respectively. Finally, diene-diene RCM to form the triene was explored.13b,c Using Grubbs’ first and second generation catalysts and the Grubbs-Hoveyda-II catalyst, RCM occurred to form substantial quantities of undesired diene product (30-40%). The indenylidene analogue of the first generation Grubbs metathesis catalyst27 was more selective for triene formation, although modest yields were obtained, perhaps due to the lack of a conformational biasing element in the form of a C19 substituent. Triene formation in this manner followed by removal of the MOM protecting group completed the total syntheses of trienomycins A and F in 16 steps (LLS). This sequence is 14 steps (LLS) shorter than the prior syntheses of trienomycins A and F,12a,b and 8 steps (LLS) shorter than any prior synthesis of a triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycin.

Scheme 4.

Union of Fragment A and Fragment B and total synthesis of trienomycins A and F.a

In summary, with the exception of eribulin, a truncated derivative of halichondrin,28 all FDA approved polyketides are prepared through fermentation or semi-synthesis, as current synthetic methods cannot concisely address the preparation of such complex structures. Accordingly, our laboratory has devised a suite of catalytic methods for polyketide construction wherein the addition, exchange or removal of hydrogen is accompanied by C-C bond formation.14 As illustrated by the present total syntheses of trienomycins A and F and prior total syntheses of roxaticin,29a bryostatin 7,29b 6-deoxyerythronolide B,29c cyanolide A,29d as well as formal syntheses of rifamycin S and scytophycin C,29e application of our technology has availed the most concise routes to any member of these respective natural product families. Future studies will focus on the development of related catalytic processes that streamline synthesis by merging redox and C-C bond construction events.30,31

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0038) and the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM093905) are acknowledged for partial support of this research. DJD received partial supported from the NIH-NRSA fellowship to promote diversity in health related research. Dr. Michael Rössle is acknowledged for preliminary studies (ref. 13c). Dr. Raul R. Rodriguez is acknowledged for skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.For selected reviews on polyketide natural products, see: O'Hagan D. The Polyketide Metabolites. Ellis Horwood; Chichester, U.K.: 1991. Rimando AM, Baerson SR, editors. Polyketides Biosynthesis, Biological Activity, and Genetic Engineering. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2007.

- 2.a Newman DJ, Cragg GM. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Newman DJ, Grothaus PG, Cragg GM. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3012. doi: 10.1021/cr900019j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohr J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:2847. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000818)39:16<2847::aid-anie2847>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sait M, Hugenholtz P, Janssen PH. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4:654. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00352.x. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For selected reviews on ansamycin natural products, see: Wrona IE, Agouridas V, Panek JS. C. R. Acad. Sci., Paris. 2008;11:1483.Funayama S, Cordell GA. In: Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. Atta-ur-Rahman, editor. Vol. 23. Elsevier; New York: 2000. pp. 51–106.

- 6.For isolation of rifamycin B, see: Sensi P, Margalith P, Timbal MT. Farmaco Ed. Sci. 1959;14:146.Sensi P, Greco AM, Ballotta R. Antibiot. Chemotherapy. 1960:262.Margalith P, Beretta G. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1960;13:21.Margalith P, Pagani H. Appl. Microbiol. 1961;9:325. doi: 10.1128/am.9.4.325-334.1961.

- 7.For isolation of mycotrienols I and II and mycotrienins I and II (ansatrienins A and B), see: Weber W, Zuehner H, Damberg M, Russ P, Zeeck A. Zbl. Bakt. Hyg., Abt. Orig. C2. 1981:122.Zeeck A, Damberg M, Russ P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:59.Sugita M, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N, Sasaki T. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1982;46:1111.Sugita M, Natori Y, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Shimazu A, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1460. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1460.Sugita M, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1467. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1467.Sugita M, Natori Y, Sueda N, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1474. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1474.Sugita M, Hiramoto S, Ando C, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:799. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.799.

- 8.For isolation of trienomycins A-F, see: Umezawa I, Funayama S, Okada K, Iwasaki K, Satoh J, Masuda K, Komiyama K. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:699. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.699.Hiramoto S, Sugita M, Ando C, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1103. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1103.Funayama S, Okada K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1107. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1107.Funayama S, Okada K, Iwasaki K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1677. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1677.Nomoto H, Katsumata S, Takahashi K, Funayama S, Komiyama K, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:1677. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.479.Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Gould AE, Omura S, Komiyama K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1627.

- 9.For isolation of cytotrienin A-D, see: Zhang H-P, Kakeya H, Osada H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:1789.Kakeya H, Zhang H-P, Kobinata K, Onose R, Onozawa C, Kudo T, Osada H. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:370. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.370.Osada H, Kakeya H, Zhang H-P, Kobinata K. PCT Int. Appl. 1998 WO 9823594.

- 10.a Komiyama K, Hirokawa Y, Yamaguchi H, Funayama S, Masuda K, Anraku Y, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1987;40:1768. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Funayama S, Anraku Y, Mita A, Yang ZB, Shibata K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1988;41:1223. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kakeya H, Zhang H.-p., Kobinata K, Onose R, Onozawa C, Kudo T, Osada H. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:370. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For stereochemical assignment of the trienomycins and mycotrienins, see: Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Wong W, Gould AE, Rizzo CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7425.Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Omura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:841.Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Hosokawa N, Naganawa H, Takeuchi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2891.Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Wong W, Gould AE, Rizzo CJ, Barbosa J, Funayama S, Komiyama K, Omura S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8308.

- 12.For the total and formal syntheses of triene-ansamycins, see: Trienomycins A and F and thiazinotrienomycin E: Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Wong W, Wood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10777.Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Wong W, Wood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8316.Smith AB, III, Wan Z. J. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1491. doi: 10.1021/ol991049g.Smith AB, III, Wan Z. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:3738. doi: 10.1021/jo991958j. Mycotrienol I and mycotrienin I: Panek JS, Masse CE. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8290. doi: 10.1021/jo971793j.Masse CE, Yang M, Solomon J, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4123.Cytotrienin A, Hayashi Y, Shoji M, Ishikawa H, Yamaguchi J, Tamaru T, Imai H, Nishigaya Y, Takabe K, Kakeya H, Osada H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6657. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802079.

- 13.For syntheses of the ansatrienol and cytotrienin cores, see: Kashin D, Meyer A, Wittenberg R, Schoning K-U, Kamlage S, Kirschning A. Synthesis. 2007:304.Evano G, Schaus JV, Panek JS. Org. Lett. 2004;6:525. doi: 10.1021/ol036284k.Rössle M, Del Valle DJ, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1482. doi: 10.1021/ol200160p.

- 14.For recent reviews of C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Bower JF, Krische MJ. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011;43:107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_5.Hassan A, Krische MJ. Org. Proc. Res. Devel. 2011;15:1236. doi: 10.1021/op200195m.Moran J, Krische MJ. Pure Appl. Chem. 2012;84:1729. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-11-10-18.

- 15.a Seyferth D, Pornet J, Weinstein RM. Organometallics. 1982;1:1651. [Google Scholar]; b Schlosser M, Zellner A, Leroux F. Synthesis. 2001:1830. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans DA, Allison BD, Yang MG, Masse CE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10840. doi: 10.1021/ja011337j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Zbieg JR, Moran J, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10582. doi: 10.1021/ja2046028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McInturff EL, Yamaguchi E, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:20628. doi: 10.1021/ja311208a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Kong J-R, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16040. doi: 10.1021/ja0664786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Skucas E, Kong J-R, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7242. doi: 10.1021/ja0715896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Han SB, Kong J-R, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4133. doi: 10.1021/ol8018874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Williams VM, Kong J-R, Ko B-J, Mantri Y, Brodbelt JS, Baik M-H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16054. doi: 10.1021/ja906225n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For recent reviews, see: Molander GA, Figueroa R. Aldrichim. Acta. 2005;38:49.Molander GA, Sandrock DL. Curr. Opin. Drug Disc. Dev. 2009;12:811.Molander GA, Canturk B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9240. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904306.

- 20.For a review of B-alkyl Suzuki cross-coupling, see: Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4544. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4544::aid-anie4544>3.0.co;2-n.

- 21.After screening a wide range of ligands, RuPhos was found to be uniquely effective in the present B-alkyl Suzuki cross-coupling: Milne JE, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3028. doi: 10.1021/ja0474493.

- 22.Hiroya K, Takuma K, Inamoto K, Sakamoto T. Heterocycles. 2009;1:493. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu W, Mei Y, Kang Y, Hua Z, Jin Z. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3217. doi: 10.1021/ol0400342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Gaunt MJ, Spencer JB. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:4627. doi: 10.1021/jo015880u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.For a review of polyketide stereotetrads in natural products, see: Koskinen AMP, Karisalmi K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:677. doi: 10.1039/b417466f.

- 26.Use of magnesium bromide in the presence of both dimethyl sulfide and 1,3-dimethoxybenzene are required for efficient PMB ether cleavage in the presence of the 1,3-diene: Onoda T, Shirai R, Iwasaki S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:1443.Jung ME, Koch P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:6051.

- 27.Fürstner A, Grabowski J, Lehmann CW. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8275. doi: 10.1021/jo991021i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Presently, the manufacturing route to eribulin involves 41 steps (longest linear sequence) and 72 total steps, impeding access to large quantities of the drug: Chase CE, Fang FG, Lewis BM, Wilkie GD, Schnaderbeck MJ, Zhu X. Synlett. 2013:323.Austad BC, Benayoud F, Calkins TL, Campagna S, Chase CE, Choi H.-w., Christ W, Costanzo R, Cutter J, Endo A, Fang FG, Hu Y, Lewis BM, Lewis MD, McKenna S, Noland TA, Orr JD, Pesant M, Schnaderbeck MJ, Wilkie GD, Abe T, Asai N, Asai Y, Kayano A, Kimoto Y, Komatsu Y, Kubota M, Kuroda H, Mizuno M, Nakamura T, Omae T, Ozeki N, Suzuki T, Takigawa T, Watanabe T, Yoshizawa K. Synlett. 2013:327.Austad BC, Calkins TL, Chase CE, Fang FG, Horstmann TE, Hu Y, Lewis BM, Niu X, Noland TA, Orr JD, Schaderbeck MJ, Zhang H, Asakawa N, Asai N, Chiba H, Hasebe T, Hoshino Y, Ishizuka H, Kajima T, Kayano A, Komatsu Y, Kubota M, Kuroda H, Miyazawa M, Tagami K, Watanabe T. Synlett. 2013:333.

- 29.For total and formal syntheses of polyketide natural products via C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Han SB, Hassan A, Kim I-S, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15559. doi: 10.1021/ja1082798.Lu Y, Woo SK, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13876. doi: 10.1021/ja205673e.Gao X, Woo SK, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;134:4223. doi: 10.1021/ja4008722.Waldeck AR, Krische MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4470. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300843.Gao X, Han H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12795. doi: 10.1021/ja204570w.

- 30.For a review of “redox economy”, see: Baran PS, Hoffmann RW, Burns NZ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806086.

- 31.“The ideal synthesis creates a complex skeleton... in a sequence only of successive construction reactions involving no intermediary refunctionalizations, and leading directly to the structure of the target, not only its skeleton but also its correctly placed functionality.” Hendrickson JB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:5784.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.