Abstract

Objectives

Proliferating adult stem cells in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus have the capacity not only to divide, but also to differentiate into neurons and integrate into the hippocampal circuitry. The present study identifies several hippocampal genes putatively regulated by zinc and tests the hypothesis that zinc deficiency impairs neuronal stem cell differentiation.

Methods

Genes that regulate neurogenic processes were identified using microarray analysis of hippocampal mRNA isolated from adult rats fed zinc-adequate or zinc-deficient (ZD) diets. We directly tested our hypothesis with cultured human neuronal precursor cells (NT2), stimulated to differentiate into post-mitotic neurons by retinoic acid (RA), along with immunocytochemistry and western analysis.

Results

Microarray analysis revealed the regulation of genes involved in cellular proliferation. This analysis also identified a number of genes known to be involved in neuronal differentiation, including the nuclear RA receptor, retinoid X receptor (RXR), doublecortin, and a transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) binding protein (P < 0.05). Zinc deficiency significantly reduced RA-induced expression of the neuronal marker proteins doublecortin and β-tubulin type III (TuJ1) to 40% of control levels (P < 0.01). This impairment of differentiation may be partially mediated by alterations in TGF-β signaling. The TGF-β type II receptor, responsible for binding TGF-β during neuronal differentiation, was increased 14-fold in NT2 cells treated with RA (P < 0.001). However, this increase was decreased by 60% in ZD RA-treated cells (P < 0.001).

Discussion

This research identifies target genes that are involved in governing neurogenesis under ZD conditions and suggests an important role for TGF-β and the trace metal zinc in regulating neuronal differentiation.

Keywords: Hippocampus, Neurogenesis, NT2, RXR, TGF-β

Introduction

Neurogenesis, the processes by which new neurons are generated in the brain, is not limited to the developmental period. In fact, it is now well recognized that stem cells in the human hippocampus and the subventricular zone (SVZ) are capable not only of dividing throughout the lifespan, but also of differentiating into mature and functional neurons. Proliferating cells of the SVZ migrate along the rostral migratory stream to become neurons that populate the olfactory bulb.1 After asymmetric division, the cells in the subgranular layer (SGL) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus undergo neuronal differentiation and migrate into the granular cell layer (GCL) where they can integrate into the hippocampal circuitry.2,3

Previous work has shown that the essential trace element zinc is an important factor for the regulation of neuronal stem cell proliferation during development. Maternal zinc deficiency significantly reduced expression of the stem cell marker nestin in the embryonic and post-natal rat brain.4 More recent work showed that dietary zinc deficiency significantly reduced the number of Ki67-positive stem cells in both the SGL and GCL of the adult rat dentate gyrus. Zinc deficiency also impairs proliferation and survival of human neuronal precursor cells.5 Thus, it appears that zinc is needed for stem cell proliferation both during development and in the adult brain. Previous work has identified a number of p53-dependent genes, including the mRNA for transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and retinoblastoma-1 (Rb1) that are regulated by zinc deficiency in neuronal precursor cells.5

There is also evidence that zinc plays a role in the regulation of adult neurogenesis via control of neuronal differentiation.6 Five weeks of zinc deficiency reduced the number of immature neurons in the dentate gyrus labeled with doublecortin (DCX). However, because apoptosis is increased by zinc deficiency,6,5 it is difficult to determine whether this decrease in DCX is due to reduced differentiation or a reduction in the number of precursor cells that have the potential to undergo differentiation.

To test the hypothesis that zinc is needed for the molecular mechanisms associated with proliferation of adult stem cells in the brain and their differentiation into a neuronal phenotype, we first subjected hippocampal samples isolated from zinc-adequate (ZA), zinc-deficient (ZD), and pair-fed (PF) rats to cDNA microarray analysis. This enabled us to identify a number of zinc-regulated gene targets, as well as develop specific hypotheses about the role of zinc in mechanisms such as TGF-β signaling that control neuronal differentiation. Because the subpopulation of proliferating cells in the adult hippocampus is small and clearly reduced in number by zinc deficiency, to test these hypotheses we employed a well-characterized model of neuronal precursor proliferation and differentiation, the human embryonal carcinoma stem cell line, NTERA-2/clone D1 (NT2).7 Numerous studies have demonstrated the ability of NT2 precursors to differentiate into a post-mitotic neuronal phenotype (NT2-N) in vitro following culture with 10 µM retinoic acid (RA). As we can grow these cells in a reduced zinc environment, they are a valuable model not only to test the hypothesis that zinc deficiency impairs neuronal differentiation, but also to examine the molecular mechanisms, identified in vivo, that may be responsible for the role of zinc in neuronal differentiation and neurogenesis.

Methods

Animal care

Two-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were individually housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-hour light–dark cycle. Rats were maintained on commercially prepared (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), isocaloric, ZA (30 ppm), or ZD (1 ppm) diets for 3 weeks (n = 3/group). To control for zinc deficiency-induced anorexia, an additional group of PF (30 ppm) rats were fed a weighed amount of ZA food equal to that eaten by the ZD rats on a daily basis. Animals were euthanized with carbon dioxide before decapitation and collection of hippocampal tissue.

Microarray hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from hippocampus using TRIzol extraction (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies). RNA purity and quantity were determined by spectrophotometry, and ethidium bromide visualization after electrophoresis on a denaturing formaldehyde-agarose gel confirmed the intact nature of the isolated RNA. Ten micrograms of each sample was prepared individually using RNeasy Mini-prep with DNase digestion according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of prepared RNA using SuperScript Double Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA quality and quantity were analyzed using a bioanalyzer and spectrophotometer (Nanodrop-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Hippocampal gene expression was analyzed using Roche/Nimblegen 12-plex rat microarray. cDNA samples were labeled and hybridized according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, double-stranded cDNA was denatured at 98°C for 10 minutes before moving to ice and adding a Cy3-labeled dNTP/Klenow master mix. After 2 hours of incubation at 37°C in the dark, the reaction was stopped with 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 5 M NaCl. Cy3-labeled cDNA was precipitated with isopropanol and pelleted by centrifugation at 12 000 × g. Pellets were dried in a SpeedVac and reconstituted in water. Concentration of the samples was determined by NanoDrop. The samples were then dried again in the speed vac, resuspended in the appropriate amount of Hyb mix, vortexed, and denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes. Samples were loaded onto array slides and hybridized at 42°C overnight. Slides were scanned using GenePix software and analysis of initial scan completed with NimbleScan. Detailed data analysis was completed with ArrayStar software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Expression patterns were normalized using the quantile normalization method and mRNA abundances were considered differentially regulated when there were changes in abundance of at least 1.5-fold with P values <0.05. Pathway analysis was completed using www.pantherdb.com. Additionally, specific information about differentially regulated genes was obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene.

Human neuron cultures

Human NT2 teratocarcinoma cells (Ntera2/D1, Stratgene, La Jolla, CA, USA) were cultured in 75 mm2 flasks and maintained in a 37°C humidified chamber containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were grown as previously described in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), 100 µg/ml of penicillin, 100 µg/ml of streptomycin, 0.25 µg/ml of amphotericin B (Sigma Chemicals), and 0.5 µg/ml of gentamicin (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, MD, USA).8

To induce neuronal differentiation, aggregate NT2 cell cultures were plated to approximately 30% confluence and treated with 10 µM RA for 2 weeks. Fresh media containing RA was provided approximately every 3 days and cells were monitored for growth and morphological changes for the duration of treatment. Cells treated with RA were shielded from light to prevent photo-destruction of the RA.

To induce zinc deficiency in NT2 cultures, media was supplemented with serum that was first mixed with 10% Chelex-100 at 4°C overnight according to the method described in Ho et al.9 ZD media was made by the addition of Chelex-treated serum to DMEM (final serum concentration of 10%) followed by filtering to remove Chelex beads and sterilize the media. ZA media was prepared by the addition of 10% serum to DMEM without Chelex treatment.

Immunocytochemistry

NT2 cells (n = 3 dishes/condition) were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized with Triton X-100 for 5 minutes. After blocking with bovine serum albumin for 10 minutes, cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse anti-human β-tubulin type III (TuJ1) monoclonal antibody (1:500, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA). Cells were then washed and incubated with a donkey anti-mouse fluorescently labeled secondary antibody conjugated to Cy3 (1:250). Cells were washed and nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 20 minutes and mounted onto microscope slides with a commercially prepared anti-fade mounting medium (FluorSave Reagent, Calbiochem-Novabiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) and examined via fluorescent microscopy (Nikon Microphot-FX). Photomicrographs were produced using exposure times that were held constant to permit comparisons between treatment groups.

Western blot analysis

NT2 cells were harvested in Triton X-100 lysis buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail. Western blot analysis was performed with modifications to previously described methods.5 Samples (n = 5/condition) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a 10% polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membrane on ice. The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween-20 (TBS-T) and non-fat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a mouse anti-human antibody for TuJ1, or a rabbit anti-human antibody for TGF-µ RI or TGF-β RII (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Membranes were then washed and incubated with their corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in TBS-T or corresponding IRDye infrared dyes (1:20 000). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using either Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and then exposed to X-ray film (Kodak X-OMAT AR film, Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) or using the Odyssey infrared detection method with corresponding software (LI-COR Biosciences, NE, USA).

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

Media and cell samples were digested in concentrated Seastar Optima® (Fisher) nitric acid (HNO3) and diluted in 2% HNO3 (0.44 M HNO3) in Milli-Q (18.3 MΩ) water. Zinc concentrations were measured with an Agilent® 7500cs single collector Quadrupole-ICP-MS equipped with an octopole collision/reaction cell (CRC), operated under hot plasma (1500 W) conditions. The sample introduction included a 100 µl/minute self-aspirating concentric PFA nebulizer (ESITM), a Scott-type quartz spray chamber, a quartz torch with an inbuilt quartz injector (2.5 mm i.d.), and nickel sampler and skimmer cones. The octopole CRC is operated by utilizing H2 gas (only reaction mode/reaction cell), at 4.7 ml/minute. NT2 cell zinc concentrations are reported as micrograms of zinc/mg cell protein.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by a Newman–Keuls post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (Prism; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Zinc deficiency regulates hippocampal genes involved in neuronal proliferation and differentiation

As expected, 3 weeks of zinc deficiency resulted in reductions in food intake that were responsible for significant decreases in body weights of ZD rats compared to rats fed the ZA diet (303 ± 29 vs. 360 ± 13 g, P < 0.05). Differences in food intake were controlled for by daily pair-feeding of an additional group of ZA rats with the amount of food eaten by the ZD rats. Thus, ZD and PF rats (311 ± 31 g) both had reduced body weights compared to ZA rats.

Microarray analysis of hippocampal mRNA isolated from adult rats fed ZA, ZD, or PF diets identified 185 genes that met the inclusion criteria for differential expression. Of these, pathway analysis determined that 11 genes were previously shown to be involved in the regulation of cellular proliferation (Table 1), 5 of which were down-regulated in response to ZD and 6 of which were up-regulated. Additionally, 15 genes involved in regulation of neuronal differentiation were identified (Table 2), 12 of which were decreased by zinc deficiency. Furthermore, with the exception of cops8, the expression profiles of the genes reported here did not differ in PF animals.

Table 1.

Zinc regulation of hippocampal genes involved in neuronal proliferation

| Seq. ID | Name | Gene | Function | ZD/ZA* | P | PF/ZA** | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_133411 | ATP-binding cassette | abcc4 | Proliferation | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.18 |

| XM_001075150 | Similar to la related protein isoform 2 | larp1 | Proliferation | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.8 | 0.16 |

| XM_001064503 | Similar to COP9 homolog | cops7b | Proliferation | 0.6 | 0.02 | 1.0 | 0.86 |

| XM_001067440 | Similar to homeobox prospero-like protein PROX1 | prox1 | Proliferation | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| XM_001070343 | Similar to CD34 antigen | cd34 | Proliferation | 0.7 | 0.04 | 1.3 | 0.30 |

| NM_001013227 | COP9 (constitutive photomorphogenic) homolog | cops8 | Proliferation | 1.5 | 0.04 | 1.4 | 0.03 |

| NM_053857 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 | eif4ebp1 | Proliferation | 1.7 | 0.03 | 1.5 | 0.11 |

| NM_001012464 | Telomeric repeat binding factor 1 | terf1 | Anti-proliferation | 1.5 | 0.05 | 1.6 | 0.12 |

| NM_017060 | HRAS-like suppressor | hrasls3 | Anti-proliferation | 1.5 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.43 |

| XM_001063428 | Similar to Sestrin-1 (p53-regulated protein PA26) | sesn1 | Anti-proliferation | 1.5 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 0.24 |

| NM_022391 | Pituitary tumor-transforming 1 | pttg1 | Anti-proliferation | 1.6 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 0.34 |

mRNA abundance in ZD animals relative to ZA, ad-libitum fed controls.

mRNA abundance in PF animals relative to ZA, ad-libitum fed controls.

Table 2.

Zinc regulation of hippocampal genes involved in neuronal differentiation

| Seq. ID | Name | Gene | Function | ZD/ ZA* |

P | PF/ ZA** |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001014163 | Cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation 1 | cend1 | Differentiation | 0.5 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 0.39 |

| XM_001076821 | Similar to serine/threonine kinase 11 | stk11 | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.5 | 0.11 |

| NM_001015020 | TG interacting factor | tgif | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 0.65 |

| NM_053765 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase | gne | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.54 |

| NM_012607 | Neurofilament, heavy polypeptide | nefh | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.05 | 1.0 | 0.78 |

| NM_021587 | Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 1 | ltbp1 | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.02 | 1.1 | 0.59 |

| NM_012805 | Retinoid X receptor alpha | rxra | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.25 |

| XM_001061267 | Similar to AFG3-like protein 2 (paraplegin-like protein) | afg3l2 | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 0.92 |

| XM_001069612 | Similar to ephrin receptor EphB2 isoform 2 precursor | ephb2 | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 0.66 |

| XM_001081351 | Ppar binding protein 1 | med1 | Differentiation | 0.6 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 0.88 |

| XM_234988 | Similar to BTB (POZ) domain containing 11 isoform 1 | btbd11 | Differentiation | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.33 |

| NM_053379 | Doublecortin | dcx | Differentiation | 0.7 | 0.05 | 0.8 | 0.23 |

| NM_024375 | Growth differentiation factor 10 | gdf10 | Differentiation | 1.5 | 0.02 | 1.2 | 0.44 |

| NM_001012219 | LIM homeobox protein 8 | lhx8 | Differentiation | 1.7 | 0.05 | 1.0 | 0.98 |

| NM_053349 | SRY-box 11 | sox11 | Differentiation | 1.7 | 0.02 | 0.9 | 0.50 |

mRNA abundance in ZD animals relative to ZA, ad-libitum fed controls.

mRNA abundance in PF animals relative to ZA, ad-libitum fed controls.

Zinc deficiency impairs neuronal differentiation

Zinc chelation resulted in an approximately 62% decrease in the amount of zinc present in medium (14.15 ± 0.89 µg/l) compared to the ZA medium containing non-chelated serum (37.75 ± 0.92 µg/l). Furthermore, ICPMS analysis showed that NT2 cells exposed to ZD medium for 48 hours contained 25% less zinc than cells grown in ZA medium (0.026 ± 0.003 vs. 0.035 ± 0.007 µg Zn/mg protein).

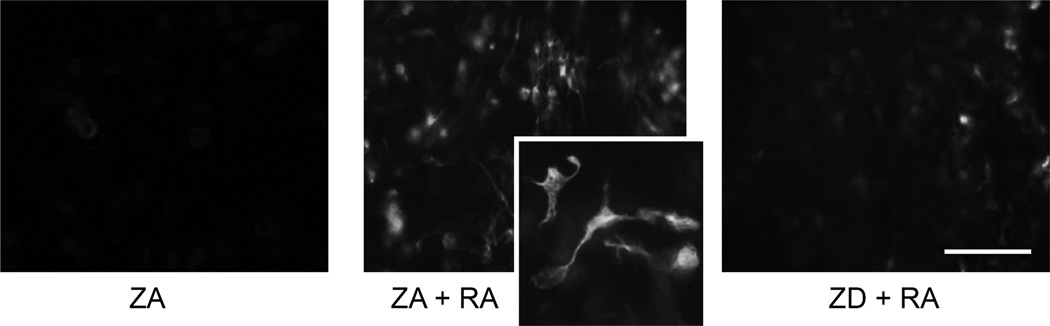

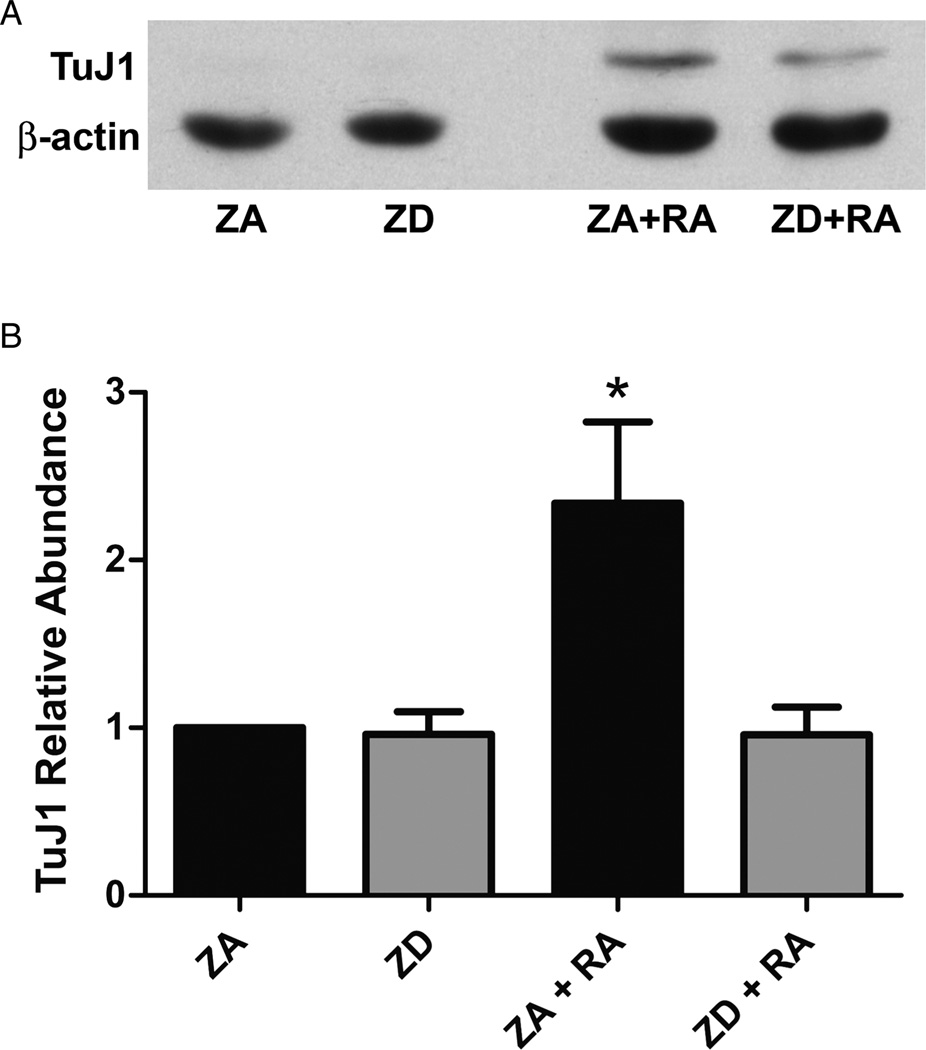

As expected, treatment of ZA NT2 cells with RA resulted in morphological changes associated with differentiation of NT2 cells into a neuronal phenotype including neurite outgrowth and the presence of growth cones, as well as evidence of increased expression of the early neuronal marker TuJ1. Zinc deficiency impaired the appearance of these indices of RA-induced neuronal differentiation (Fig. 1). Western blot analysis not only confirmed the ability of RA treatment to induce expression of TuJ1 abundance (n = 5, Fig. 2A) but revealed that this expression was reduced by 40% in RA-treated cultures grown in ZD media (P = 0.004, Fig. 2B).

Figure 1.

The effect of zinc on immunostaining of the neuronal differentiation marker TuJ1 during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. TuJ1 immunofluorescent staining in NT2 cells under ZA conditions with no exposure to RA and following 2-week exposure to 10 µM RA under ZA and ZD conditions. Scale bar represents 50 µm.

Figure 2.

The effect of zinc on expression of the neuronal differentiation marker TuJ1 during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. (A) Representative western blot of TuJ1 expression in cell lysates prepared from ZA and ZD NT2 cells as well as cells in both zinc conditions treated with RA (ZA + RA, ZD + RA). (B) Western blot analysis of relative TuJ1 protein abundance in ZA and ZD cells with and without RA. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 5). *Indicates that ZA cells exposed to 10 µM RA for 2 weeks were significantly different from all other conditions (P < 0.004).

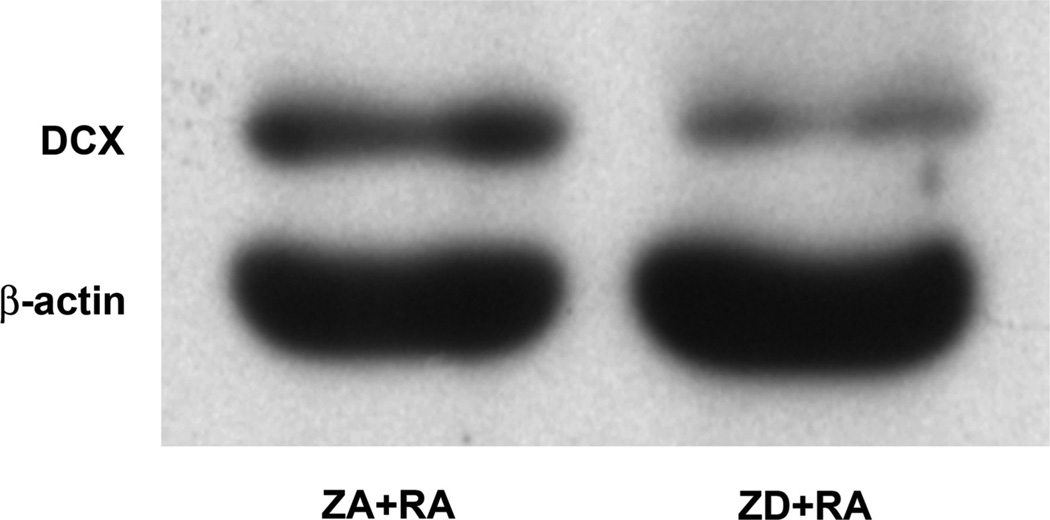

The effect of zinc deficiency on the ability of RA to induce neuronal differentiation was also assessed using the neuronal marker DCX. While RA treatment of ZA cultures (ZA + RA) resulted in the appearance of DCX after 2 weeks, DCX expression was impaired in RA-treated ZD cultures (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of zinc on DCX expression during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. Representative western blot of DCX expression in cell lysates prepared from ZA and ZD NT2 cells after 2-week exposure to 10 µM RA.

TGF-β receptor regulation during neuronal differentiation

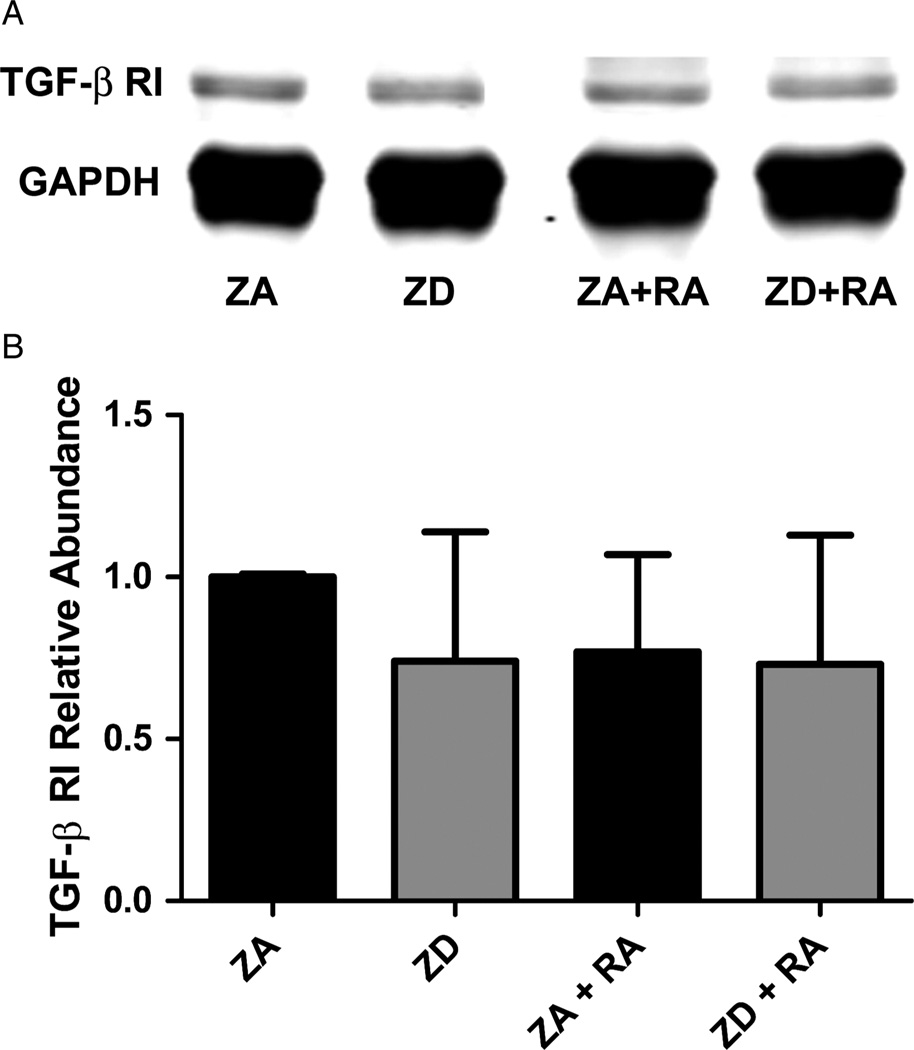

TGF-β receptor I

Western blot analysis of TGF-β RI protein expression (n = 5/condition) revealed that this receptor isoform is expressed by both neuronal precursors and mature NT2-N neurons (Fig. 4A). Zinc deficiency neither caused a significant change in the expression of this receptor, nor were there significant differences across treatment groups (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

The effect of zinc on TGF-β RI expression during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. (A) Representative western blot of TGF-β RI expression in cell lysates prepared from ZA and ZD NT2 cells as well as cells in both zinc conditions treated with RA (ZA + RA, ZD + RA). (B) Western blot analysis of relative TGF-β RI protein abundance in ZA and ZD cells with and without RA. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 5). No significant differences were found among groups.

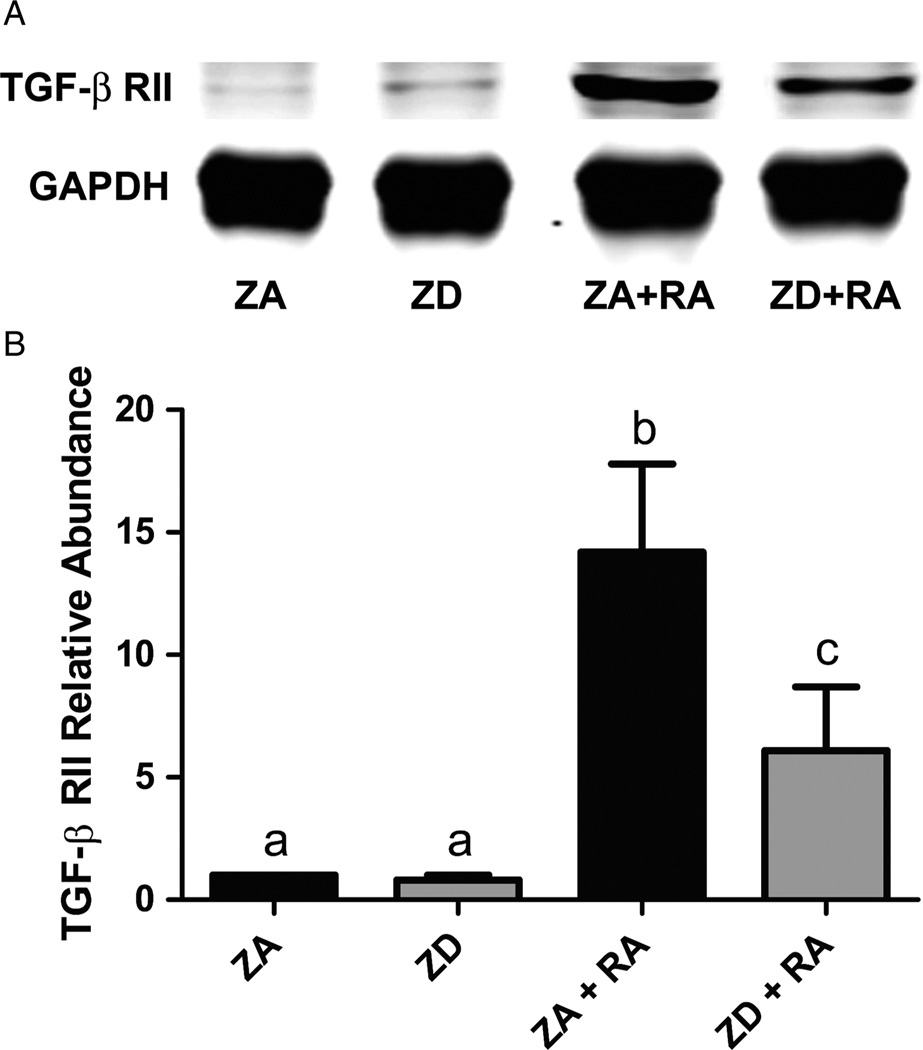

TGF-β receptor II

Western blot analysis of the TGF-β type II receptor revealed that this isoform is expressed in very low abundances in both ZA and ZD NT2 neuronal precursor cells. Treatment of NT2 cells with RA, however, resulted in a 14-fold increase in TGF-β RII expression (P < 0.0001). Fig. 5 shows that this RA-induced increase in expression was decreased by 60% in ZD cells (P < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

The effect of zinc on TGF-β RII expression during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. (A) Representative western blot of TGF-β RII expression in cell lysates prepared from ZA and ZD NT2 cells as well as cells in both zinc conditions treated with RA (ZA + RA, ZD + RA). (B) Western blot analysis of relative TGF-β RII protein abundance in ZA and ZD cells with and without RA. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3–5). aIndicates that ZA cells exposed to 10 µM RA for 2 weeks were significantly different from all other conditions (P < 0.0001). bIndicates that ZD cells treated with RA were significantly different from all other conditions (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Previous work in our lab demonstrated that zinc deficiency impairs proliferation of neuronal precursor cells in the adult hippocampus.5 This observation has now been confirmed by others.6,10 While the current work identified a number of new genes that may play a role in ZD proliferation in the dentate gyrus, given what we know about the role of zinc in neuronal stem cell proliferation, the finding that zinc regulates proliferation-specific genes in this region of the brain is not surprising. The current analysis did however identify several putative zinc-regulated gene targets in the hippocampus that have not been previously reported. This included the down-regulation of a number of genes associated with proliferation as well as up-regulation of anti-proliferative genes such as the p53-regulated protein Sestrin-1. This is consistent with previous work showing a role for the transcription factor p53 in the zinc-regulated control of the cell cycle in neuronal precursor cells.5

It is important to note that because zinc deficiency has been shown to induce anorexic-like feeding behaviors in rats, PF animals were given weighed amounts of ZA rat chow equal to the amounts consumed by animals on ZD diets to control for potential contributions of caloric restriction on alterations in gene expression. The gene, cops8, encodes a subunit of the COP9 protein complex which has roles in cell cycle progression and DNA repair and was significantly up-regulated in PF animals.11 With the exception of the cops8 gene, this experimental model confirms that the changes in gene expression profiles were, in fact, a result of modifications in zinc status, rather than an effect of caloric restriction.

The current analysis also revealed a number of genes associated with neuronal differentiation. For example, in the microarray study expression of DCX mRNA, an early marker of neuronal differentiation,12 was reduced in ZD animals to 70% of ZA control levels (P < 0.05). Follow-up analysis of DCX protein levels using western analysis in zinc-restricted neuronal precursor cells also showed a robust decline in DCX expression, consistent with previous reports of reductions in DCX from mouse hippocampus following 5 weeks of zinc deficiency.6 The finding that dietary zinc deficiency disrupts expression of genes such as DCX associated with neuronal differentiation in the hippocampus led us to directly test the hypothesis that zinc deficiency impairs neuronal differentiation.

Zinc deficiency impairs RA-induced neuronal differentiation

To test this hypothesis and examine mechanisms involved in zinc regulation of differentiation we employed the well-characterized human NT2 neuronal precursor cell line. While terminal differentiation of these cells typically requires 4 weeks of RA treatment,13 we have observed the appearance of TuJ1 within 1 week of RA administration, consistent with the use of TuJ1 as a marker of early neuronal commitment and differentiation.12

Zinc deprivation impaired the ability of RA to induce NT2 differentiation as evidenced by morphological indicators, TuJ1 expression, and DCX expression. These results suggest that zinc is required for neuronal differentiation, a finding with implications for hippocampal function. Not only is the hippocampus a major site of adult neurogenesis, it is one of the regions of the brain with the highest concentrations of zinc. Furthermore, previous work has shown that while there were a number of brain regions such as the amygdala, thalamus, and hypothalamus with trends toward reductions in total zinc content, it was the hippocampus that was the only brain region with significantly reduced zinc levels after dietary zinc deficiency.14

RXR-mediated mechanisms of zinc-regulated neuronal differentiation

The initial microarray analysis of hippocampus isolated from ZA and ZD rats revealed a number of interesting putative mechanisms that may be responsible for impaired neuronal differentiation during zinc deficiency. For example, a gene known as cend1 that plays the dual role of inducing cell cycle exit as well as neuronal differentiation was down-regulated to 50% of control levels (P < 0.05).15,16 Zinc deficiency also decreased the abundance of the mRNA that codes for the nuclear RA receptor, RXRα. Under normal circumstances, RA is translocated to the nucleus of the cell where it acts as a ligand for two isoforms of retinoid receptors; RA receptor (RAR) and retinoic X receptor (RXR). These nuclear retinoid receptors form RAR/RXR heterodimers and bind to specific RA response elements on the 5′-flanking regions of target genes.17 In this way RA acts to regulate genes involved in neuronal differentiation.18 Given that NT2 cells clearly differentiate into post-mitotic neurons in the presence of RA, the finding that RXR is down-regulated by zinc deficiency in the hippocampus suggests that RXR plays a role in the mechanisms responsible for zinc-regulated neuronal differentiation. This is consistent with the current work showing that zinc deficiency not only down-regulates RXR, but also impairs differentiation of human neuronal precursor cells. Future work will be needed to elucidate the specific role of the alpha isoform of RXR, identified in this work, in zinc-specific regulation of neuronal differentiation.

While nuclear receptors such as RXR and other transcription factors including NeuroD119 and the cAMP response element-binding protein, CREB,20 have now been implicated in the control of neuronal differentiation, it should also be recognized that epigenetic factors including histone modifications and DNA methylation are likely at work.21 Epigenetics appear to play a role in the control of the phenotypic fate of stem cells in the adult brain. For example, MeCP2, which plays a role in DNA methylation, has been shown to be involved in the suppression of glial genes (such as GAP) in neurons22 and overexpression of MeCP2 increases neuronal differentiation.23 Furthermore, histone methyltransferase MLL1 is highly expressed in the SVZ and the olfactory bulb where is appears to play a role in both stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis.24 Thus, the role of zinc in the epigenetic control of gene expression leading to neuronal differentiation of stem cells in the adult brain is an important area for future research.

TGF-β-mediated mechanisms of zinc-regulated neuronal differentiation

Previous work has demonstrated a role for TGF-β in governing proliferation and survival of NT2 cells.5 Consistent with this earlier report, the data presented here show that zinc deficiency decreased the gene for the latent TGF-β binding protein-1 (LTBP-1) to 60% of control (P < 0.01). LTBP-1 has been shown to play an important role in TGF-β availability by chaperoning TGF-β ligands to cell membranes and potentiating their secretion and activation.25 This observation led us to hypothesize a role for TGF-β receptors in the zinc regulation of neuronal differentiation.

There are three distinct isoforms of the TGF-β receptor, known as receptor types I, II, and III. Receptor types I and II have been identified extensively throughout the CNS and are together responsible for directing TGF-β signal transduction.26,27 TGF-β signal transduction is initiated by the ligand binding and activating the TGF-β type II receptor. This recruits and activates the type I receptor, forming a heterodimeric complex consisting of two copies of each receptor isoform and the bound ligand. Following receptor activation, the receptor-regulated Smad2/3 (R-Smad) becomes activated through association with the RI isoforms of the receptor complex and then binds to the co-Smad (Smad4) protein in the cell cytosol. This R-Smad/co-Smad complex translocates to the nucleus of the cell, where it acts as a transcription factor to regulate gene expression and control neuronal differentiation.26,28–31

Previous work has shown that the TGF-β type II receptor is not present in NT2 precursor cells, but that RA-induced differentiation leads to expression of this receptor isoform that is detectable after 1 week of RA treatment.32 In contrast, the type I receptor appears to be present in both NT2 precursors and mature NT2-N neurons.32 Consistent with this report, the type I receptor (RI) was expressed in neuronal precursors as well as in cells undergoing RA-induced differentiation in the current work. While previous work has shown that inhibition of RI-impaired differentiation,33 expression of this receptor was not altered by zinc deficiency. However, TGF-β RII was present at very low levels in neuronal precursors and RA exposure resulted in a dramatic increase in expression. Importantly, the increase in RII expression in differentiating cells was significantly impaired by zinc deficiency. It should be noted that rodent brains deficient in TGF-β RII showed signs of neurodegeneration including a decline in neuronal cell number, synaptic function, and dendritic stability, as well as increasing β-amyloid plaque deposition.34 Thus, future work will be needed to study the possible consequences of zinc deficiency-induced changes in TGF-β RII expression on TGF-β signal transduction in neuronal stem cells and the possible implications of zinc deficiency for the development of neurodegenerative processes.

This work has shown that the trace element zinc is an essential factor for neuronal differentiation and has used both in vivo and in vitro models to identify several putative mechanistic targets such as the nuclear receptor RXR and the TGF-β type II receptor. Given that approximately 10% of Americans consume less than half of the recommended dietary allowance for zinc, and zinc deficiency is even more prevalent worldwide with nearly 50% of the population at risk for inadequate dietary zinc consumption,35,36 the role of zinc in the brain is of clinical importance. Furthermore, because neurogenesis takes place from gestation through adulthood, these findings have implications not only during brain development but also throughout the lifespan.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Charles Badland for his excellent assistance in producing the figures presented in this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge Dr William Landing and Angela Dial for their gracious assistance in measuring zinc status in cells and medium via ICPMS.

References

- 1.Mendoza-Torreblanca JG, Martinez-Martinez E, Tapia-Rodriguez M, Ramirez-Hernandez R, Gutierrez-Ospina G. The rostral migratory stream is a neurogenic niche that predominantly engenders periglomerular cells: in vivo evidence in the adult rat brain. Neurosci Res. 2008;60(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415(6875):1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang FD, Bian W, Kong LW, Zhao FJ, Guo JS, Jing NH. Maternal zinc deficiency impairs brain nestin expression in prenatal and postnatal mice. Cell Res. 2001;11:135–141. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corniola RS, Tassabehji NM, Hare J, Sharma G, Levenson CW. Zinc deficiency impairs neuronal precursor cell proliferation and induces apoptosis via p53-mediated mechanisms. Brain Res. 2008;1237:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao HL, Zheng W, Xin N, Chi ZH, Wang ZY, Chen J, et al. Zinc deficiency reduces neurogenesis accompanied by neuronal apoptosis through caspase-dependent and – independent signaling pathways. Neurotox Res. 2009;16:416–425. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews PW. Human teratocarcinomas. Biochem Biophys. 1988;948:17–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(88)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.VanLandingham JW, Levenson CW. Effect of retinoic acid on ferritin H expression during brain development and neuronal differentiation. Nutr Neurosci. 2003;6(1):39–45. doi: 10.1080/1028415021000056041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho E, Courtemanche C, Ames B. Zinc deficiency induces oxidative DNA damage and increases p53 expression in human lung fibroblasts. J Nutr. 2003;133(8):2543–2548. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.8.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh SW, Won SJ, Hamby AM, Yoo BH, Fan Y, Sheline CT, et al. Decreased brain zinc availability reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in mice and rats. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1579–1588. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enchev RI, Schreiber A, Beuron F, Morris EP. Structural insights into the COP9 signalosome and its common architecture with the 26S proteasome lid and eIF3. Structure. 2010;18(4):518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Bohlen, Halbach O. Immunohistological markers for staging neurogenesis in adult hippocampus. 2007;329(3):409–420. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pleasure SJ, Page C, Lee VM. Pure, postmitotic, polarized human neurons derived from NTera 2 cells provide a system for expressing exogenous proteins in terminally differentiated neurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12(5):1802–1815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01802.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda A, Minami A, Takefuta S, Tochigi M, Oku N. Zinc homeostasis in the brain of adult rats fed zinc-deficient diet. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:447–452. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010301)63:5<447::AID-JNR1040>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panagiotis PK, Makri G, Thomaidou D, Geissen M, Rohrer H, Matsas R. BM88/CEND1 coordinates cell cycle exit and differentiation of neuronal precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(45):17861–17866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610973104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsimpardi L, Gaitanou M, Malnou CE, Lledo PM, Charneua P, Mastas R, et al. BM88/Cend1 expression levels are critical for proliferation and differentiation of subventricular zone-derived neural precursor cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(7):1796–1807. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maden M. Retinoic acid in the development, regeneration and maintenance of the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(10):755–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang TW, Zhang H, Parent JM. Retinoic acid regulates postnatal neurogenesis in the murine subventricular zone-olfactory bulb pathway. Development. 2005;132:2721–2732. doi: 10.1242/dev.01867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tozuka Y, Fukuda S, Namba T, Seki T, Hisatsune T. GABAergic excitation promotes neuronal differentiation in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuron. 2005;47(6):803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagasia R, Steib K, Englberger E, Herold S, Faus-Kessler T, Saxe M, et al. GABA-cAMP response element-binding protein signaling regulates maturation and survival of newly generated neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29(25):7966–7977. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1054-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh J, Eisch AJ. Epigenetics, hippocampal neurogenesis, and neuropsychiatric disorders: unraveling the genome to understand the mind. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39(1):73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohyama J, Kojima T, Takatsuka E, Yamashita T, Namiki J, Hsieh J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of neural cell differentiation plasticity in the adult mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(46):18012–18017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808417105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujimura K, Abematsu M, Kohyama J, Namihira M, Nakashima K. Neuronal differentiation of neural precursor cells is promoted by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2. Exp Neurol. 2009;219(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim DA, Huang Y, Swigut T, Mirick AL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Wysocka J, et al. Chromatin remodeling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7237):529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) binding proteins: orchestrators of TGF-beta availability. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):7409–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem. 2000;75(6):2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Cárcamo J, Zantella A, Doody J, Laiho M, et al. TGF beta signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell. 1992;71(6):1003–1014. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90395-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomes FC, Sousa Vde O, Romão L. Emerging roles for TGF-beta1 in nervous system development. 2005;23(5):413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitisin K, Saha T, Blake T, Golestaneh N, Deng M, Kim C, et al. TGF-beta signaling in development. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(399):cm1. doi: 10.1126/stke.3992007cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu J, Wu Y, Sousa N, Almeida OF. SMAD pathway mediation of BDNF and TGF beta 2 regulation of proliferation and differentiation of hippocampal granule neurons. Development. 2005;132(14):3231–3242. doi: 10.1242/dev.01893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batista D, Ferrari CC, Gage FH, Pitossi FJ. Neurogenic niche modulation by activated microglia: transforming growth factor beta increases neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(1):83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren RF, Hawver DB, Kim RS, Flanders KC. Transforming growth factor-β protects human hNT cells from degeneration induced by β-amylpid peptide: involvement of the TGF-β type II receptor. Mol Brain Res. 1997;48:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misumi S, Kim T, Jung C, Masuda T, Urakawa S, Isobe Y, et al. Enhanced neurogenesis from neural progenitor cells with G1/S-phase cell cycle arrest is mediated by transforming growth factor β1. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(6):1049–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesseur I, Zou K, Esposito L, Bard F, Berber E, Can JV, et al. Deficiency in neuronal TGF-β signaling promotes neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s pathology. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):3060–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI27341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown KH, Wuehler SE, Peerson JM. The importance of zinc in human nutrition and estimation of the global prevalence of zinc deficiency. Food Nutr Bull. 2001;22(2):113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cope EC, Levenson CW. Role of zinc in the development and treatment of mood disorders. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(6):685–689. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833df61a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]