Abstract

Recent epidemiological studies have suggested an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in lung fibrosis. Large-scale epidemiological data regarding the risk of VTE in pulmonary fibrosis-associated mortality have not been published.

Using data from the National Center for Health Statistics from 1988–2007, we determined the risk of VTE in decedents with pulmonary fibrosis in the USA.

We analysed 46,450,489 records, of which 218,991 met our criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Among these, 3,815 (1.74%) records also contained a diagnostic code for VTE. The risk of VTE in pulmonary fibrosis decedents was 34% higher than in the background population, and 44% and 54% greater than among decedents with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer, respectively. Those with VTE and pulmonary fibrosis died at a younger age than those with pulmonary fibrosis alone (females: 74.3 versus 77.4 yrs (p<0.0001); males: 72.0 versus 74.4 yrs (p<0.0001)).

Decedents with pulmonary fibrosis had a significantly greater risk of VTE. Those with VTE and pulmonary fibrosis died at a younger age than those with pulmonary fibrosis alone. These data suggest a link between a pro-fibrotic and a pro-coagulant state.

Keywords: Epidemiology, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, mortality, pulmonary fibrosis, venous thromboembolism

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, and recently published epidemiological data suggest that the burden of disease is rising. The incidence and mortality rates for IPF, and pulmonary fibrosis (PF) in general, have been increasing steadily [1–6]. IPF is a deadly disease, with amedian survival after diagnosis ranging from 3 to 5 yrs [7], and no therapy other than lung transplantation has been shown to prolong survival.

In a recently conducted epidemiological study of 920 subjects, an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) was found both before and after the onset of PF [8]. In a separate study that included all Danish PF patients from 1980–2007, a prior history of VTE was found to increase the risk of developing interstitial lung disease (ILD) [9]. Although these studies hint at a relationship between VTE and PF, large-scale epidemiological data about the risk of VTE in PF-associated mortality have not been published.

At themolecular level, activation of the coagulation cascade, via the tissue factor-dependent extrinsic pathway, and as evidenced by elevated levels of tissue factor and fibrin (the main component of clots), occurs in lung tissue from patients with IPF [10]. Data also suggest abnormalities in intrinsic anticoagulation pathways: bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with IPF reveals decreased protein C activation [11]. Furthermore, fibrinolysis appears to be dysregulated: models of lung fibrosis have revealed elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, thus promoting fibrin persistence [12].

Based on these data, we hypothesised that an excessive number of VTEs would be found in patients with IPF in decedents in the USA from 1988–2007, and that among IPF decedents, the presence of VTE would be associated with a younger age of death.

METHODS

Database

Details of the database and methods used have been published previously [6]. Briefly, we used the US Multiple Cause-of-Death mortality database (National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) [13], for which the NCHS compiles data from all death certificates in the USA and releases the figures in annual, public-use files. For this study, we analysed files from 1988 to 2007 [13, 14]. An annual file contains >2 million decedent records, and each record contains decedent demographics, ≤20 conditions related to death within a section of the record the NCHS calls the “record axis”, and the ultimate underlying cause of death (UCD), defined by the World Health Organization as “the disease or injury which initiated the train of events leading to death” [14, 15].

From 1988–1998, the NCHS coded conditions related to death using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 [16]. Thereafter, the NCHS coded conditions related to death using the ICD-10 [14]. All data contained in these database files have been de-identified and are publicly recorded; therefore, institutional review board approval for this study was not required.

Case definitions

We included files from any decedent from the USA with IPF, as defined by the following ICD codes: from 1988 to 1998, ICD-9 codes 515 (post-inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis (PIPF)) and 515.6 (IPF); and thereafter, ICD-10 code J84.1 (a code that combines both PIPF and IPF). We then excluded patients with record axis codes for any condition that might be associated with secondary PF, including connective tissue diseases, radiation fibrosis, asbestosis, pneumoconiosis (including coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, talcosis and berylliosis), sarcoidosis and/or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis). In addition, we excluded patients with a concurrent diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or lung cancer. We identified three groups for comparison purposes: 1) the background population, which included decedents without IPF, lung cancer or COPD; 2) decedents with COPD (but not IPF or lung cancer); and 3) decedents with lung cancer (but not IPF). VTE disease was defined as either venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. From 1988 to 1998, we defined venous thrombosis by ICD-9 codes 451–451.8 and 453– 453.9, and pulmonary embolism by ICD-9 code 415.1, while after 1998 we used ICD-10 codes I80–I80.9, I82.8 and I82.9 to define venous thrombosis, and ICD-10 codes I26–I26.9 to define pulmonary embolism. Specifics of additional ICD-9 and ICD- 10 codes are included in the Appendix.

Statistical analysis

We used the Chi-squared test (or Mantel–Haenszel statistic where appropriate) to determine the risk of VTE in decedents with IPF in reference to the three comparator groups. We then performed logistic regression to determine the adjusted risk of VTE in decedents with IPF in reference to the three comparator groups. When comparing the risk of VTE in IPF decedents with the background population, we assessed second-order interactions between IPF and sex, age and year of diagnosis. We also used the Chi-squared statistic to compare differences in the UCD between PF decedents with or without VTE. A two-sample unpaired t-test was used to compare the mean age of death between PF decedents with or without VTE. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance in all analyses. All data were analysed using SAS® version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

From 1988 to 2007, there were 46,450,489 deaths of residents of the USA. A total of 218,991 records met our criteria for a diagnosis of IPF. Among these, 3,815 records also contained a diagnostic code for VTE (table 1), yielding a prevalence of VTE in IPF that was significantly greater than in the background population (1.74% versus 1.31%; p<0.0001). Thus, the overall odds of being diagnosed with a VTE were significantly greater in decedents with IPF than in decedents in the background population (overall OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.29–1.38). In the year-by-year analysis, the risk of VTE was greater for IPF than in the background population in every year except 2005 (p=0.25).

TABLE 1.

Decedents in the background population or with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), with and without venous thromboembolism (VTE)#

| Year | Background population | IPF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | |

| 1988 | 1831827 | 25295 | 1.36 | 6762 | 136 | 1.97 |

| 1989 | 1805702 | 24821 | 1.36 | 7321 | 151 | 2.02 |

| 1990 | 1797405 | 23709 | 1.30 | 7432 | 147 | 1.94 |

| 1991 | 1811245 | 22855 | 1.25 | 7839 | 133 | 1.67 |

| 1992 | 1813359 | 22095 | 1.25 | 8240 | 154 | 1.83 |

| 1993 | 1888488 | 21468 | 1.12 | 8661 | 135 | 1.53 |

| 1994 | 1898205 | 20944 | 1.09 | 9086 | 131 | 1.42 |

| 1995 | 1926144 | 21740 | 1.12 | 9494 | 149 | 1.55 |

| 1996 | 1924032 | 21218 | 1.09 | 10059 | 157 | 1.54 |

| 1997 | 1918141 | 20659 | 1.07 | 10719 | 148 | 1.36 |

| 1998 | 1932077 | 21203 | 1.09 | 11210 | 190 | 1.67 |

| 1999 | 1973552 | 27218 | 1.36 | 11585 | 220 | 1.86 |

| 2000 | 1984046 | 28100 | 1.40 | 12347 | 245 | 1.95 |

| 2001 | 1993694 | 28929 | 1.43 | 12664 | 235 | 1.82 |

| 2002 | 2015339 | 29426 | 1.44 | 13268 | 245 | 1.81 |

| 2003 | 2016149 | 30276 | 1.48 | 13639 | 251 | 1.81 |

| 2004 | 1972413 | 29228 | 1.46 | 13572 | 239 | 1.73 |

| 2005 | 2011508 | 30195 | 1.48 | 13736 | 223 | 1.60 |

| 2006 | 1997942 | 30670 | 1.51 | 13686 | 261 | 1.87 |

| 2007 | 1995092 | 30880 | 1.52 | 13856 | 265 | 1.88 |

| Total | 38506360 | 510929 | 1.31¶ | 215176 | 3815 | 1.74¶ |

decedents with VTE were defined as those with VTE mentioned on their death certificates as contributing to death;

overall OR 1.34, 95 % CI 1.29–1.38; p<0.0001 for association between IPF and VTE.

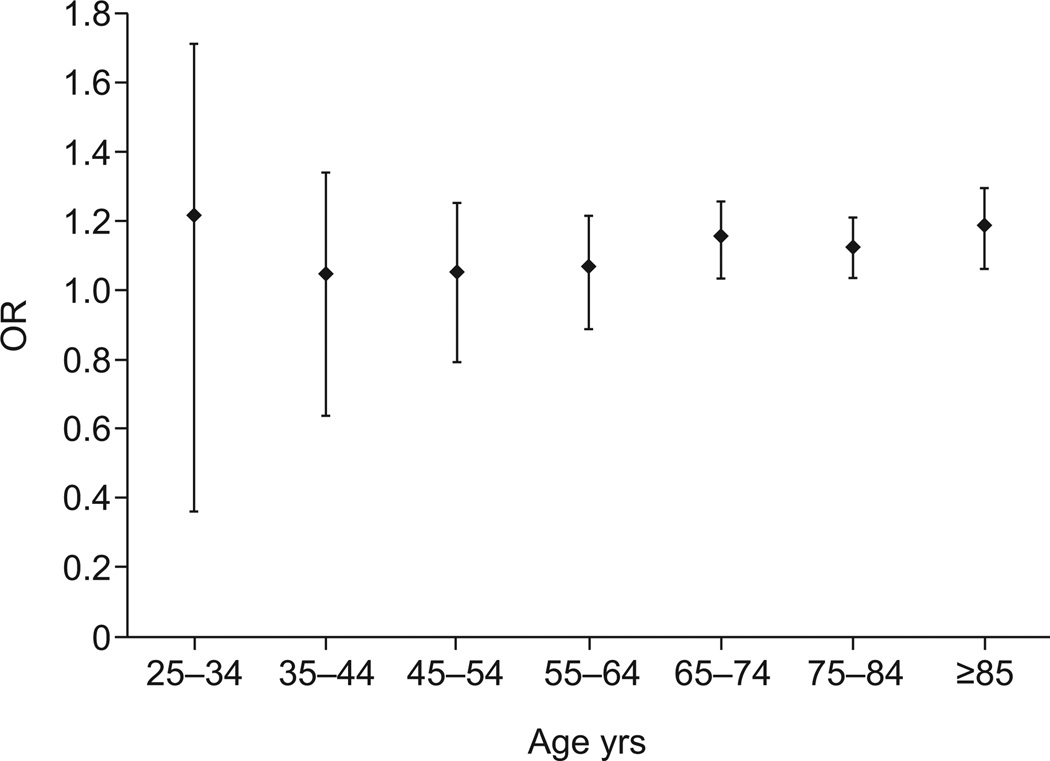

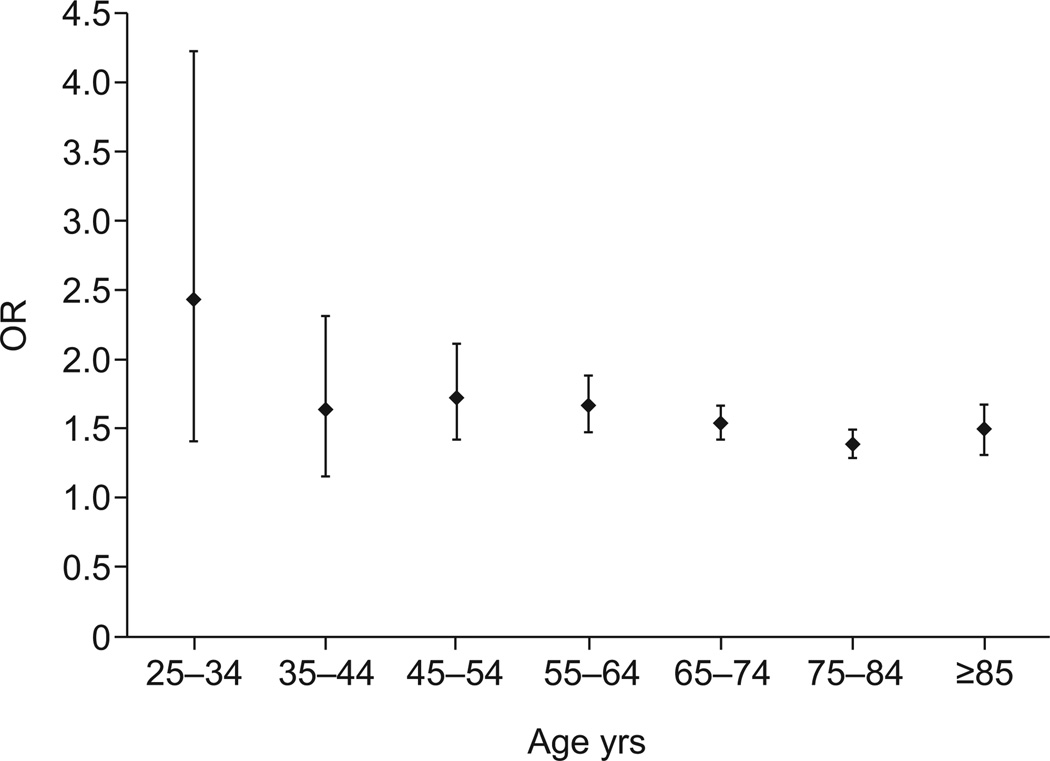

After stratifying for sex and age, female decedents with IPF in age strata 65–74 yrs, 75–84 yrs and o85 yrs, but not <65 yrs, had a significantly greater risk of VTE than the background population (fig. 1). Among male decedents with IPF, the risk of VTE was significantly greater than the background population for all age strata (fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

The overall risk of venous thromboembolic disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when compared with the background population, for females by age. The odds ratio (OR) was only significant for those in the older age groups (65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 yrs; p<0.05), while the risk was not significantly elevated in the younger age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–54 and 55–64 yrs; p=0.4830, p=0.7966, p=0.6809 and p=0.4339, respectively). Data are presented as OR with 95% CI.

FIGURE 2.

The overall risk of venous thromboembolic disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when compared with the background population, for males by age. All age groups were statistically significant (p<0.05). Data are presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI.

Using logistic regression, and adjusting for sex, age and year of death, the risk of VTE remained significantly greater in decedents with IPF than in the background population (adjusted OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.29–1.38). Among all decedents, males had a significantly lower risk of VTE (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.74–0.75) than females, and increasing age conferred a slightly lower, but significant, risk of VTE (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99–0.99). From 1988 to 2007, the overall risk of VTE increased slightly with each passing year (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.01–1.01).

When interactions between IPF and sex, age and year of death were assessed, each two-way interaction was found to be statistically significant. The risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was modified by age, sex and year of death: among decedents with IPF, increasing age, female sex and later year of death reduced the risk of VTE. β-coefficients, standard errors and p-values for the model that included these second-order interactions are reported in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted# logistic regression model for venous thromboembolism in decedents with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) compared with the background population

| Parameter | Estimate | se | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −3.4873 | 0.00703 | <0.0001 |

| Disease¶ | 0.6192 | 0.1021 | <0.0001 |

| Age per yr+ | −0.0112 | 0.000084 | <0.0001 |

| Sex§ | −0.2956 | 0.00294 | <0.0001 |

| Year of death∱ | 0.0134 | 0.000248 | <0.0001 |

| Disease × age | −0.00505 | 0.00127 | <0.0001 |

| Disease × sex | 0.3207 | 0.0331 | <0.0001 |

| Disease × year of death | −0.00926 | 0.00296 | 0.0018 |

model adjusted for age, sex, year of death, and two-way interactions between IPF and age, sex and year of death;

with IPF as the reference group;

>25 yrs of age;

with males as the reference group;

with 1988 as the reference year (coded as 1).

We assessed the effects of race and sex on the risk of VTE in decedents with IPF compared with the background population. Using logistic regression, we found that the risk of VTE remained greater for IPF decedents than those in the background population when adjusted for ethnicity and race (adjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.34–1.43). Among all decedents, when using non-Hispanic Whites as the reference population, Hispanics and non-Hispanic others (including Asians) had a lower risk of VTE (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.74–0.76 and OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.54–0.57, respectively), while non-Hispanic Blacks had an elevated risk of VTE (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.32–1.34). There were no significant two-way interactions between IPF and ethnicity or race, suggesting that the risk of VTE among IPF decedents is not further altered by the decedent’s race or ethnicity.

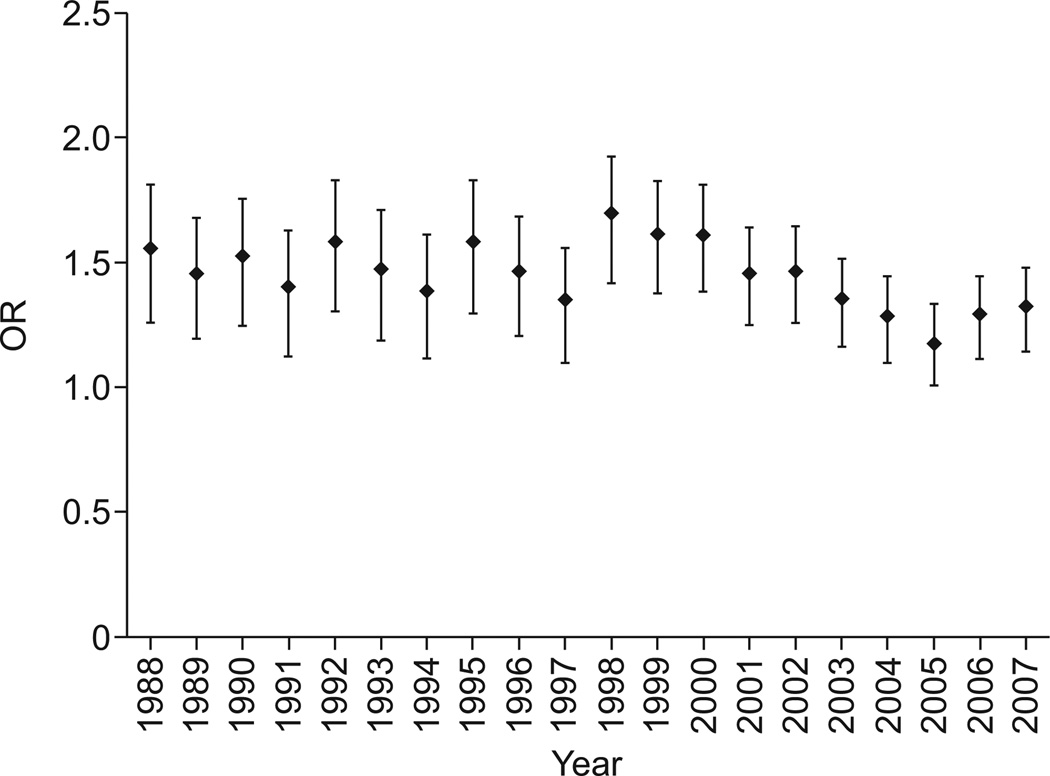

There were 3,980,364 decedents with COPD. Of these, 48,441 records also contained a code for VTE, yielding a prevalence of VTE that was significantly lower for COPD than for IPF (1.22% versus 1.74%; p<0.0001) and a risk of VTE that was significantly greater in decedents with IPF (overall OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.39–1.49) than in those with COPD (fig. 3 and table 3). The risk of VTE was greater for IPF than COPD in every year studied. Using logistic regression and adjusting for age (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98–0.99), male sex (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.97) and year of death (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.01–1.01), the risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was found to be significantly greater than in those with COPD (adjusted OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.34–1.46).

FIGURE 3.

The annual risk of venous thromboembolic disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when compared with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The odds ratio (OR) was statistically significant for all years analysed (p<0.05). Data are presented as OR with 95% CI.

TABLE 3.

Decedents with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), with and without venous thromboembolism (VTE)#

| Year | COPD | IPF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | |

| 1988 | 156682 | 2021 | 1.27 | 6762 | 136 | 1.97 |

| 1989 | 161287 | 2283 | 1.40 | 7321 | 151 | 2.02 |

| 1990 | 164755 | 2138 | 1.28 | 7432 | 147 | 1.94 |

| 1991 | 170028 | 2063 | 1.20 | 7839 | 133 | 1.67 |

| 1992 | 172495 | 2035 | 1.17 | 8240 | 154 | 1.83 |

| 1993 | 187491 | 1991 | 1.05 | 8661 | 135 | 1.53 |

| 1994 | 187828 | 1955 | 1.03 | 9086 | 131 | 1.42 |

| 1995 | 190306 | 1886 | 0.98 | 9494 | 149 | 1.55 |

| 1996 | 193942 | 2070 | 1.06 | 10059 | 157 | 1.54 |

| 1997 | 198026 | 2027 | 1.01 | 10719 | 148 | 1.36 |

| 1998 | 204277 | 2047 | 0.99 | 11210 | 190 | 1.67 |

| 1999 | 214645 | 2526 | 1.16 | 11585 | 220 | 1.86 |

| 2000 | 211138 | 2601 | 1.22 | 12347 | 245 | 1.95 |

| 2001 | 212783 | 2710 | 1.26 | 12664 | 235 | 1.82 |

| 2002 | 215402 | 2723 | 1.25 | 13268 | 245 | 1.81 |

| 2003 | 217888 | 2971 | 1.35 | 13639 | 251 | 1.81 |

| 2004 | 212259 | 2914 | 1.35 | 13572 | 239 | 1.73 |

| 2005 | 225543 | 3110 | 1.36 | 13736 | 223 | 1.60 |

| 2006 | 217401 | 3218 | 1.46 | 13686 | 261 | 1.87 |

| 2007 | 217747 | 3152 | 1.43 | 13856 | 265 | 1.88 |

| Total | 3931923 | 48441 | 1.22¶ | 215176 | 3815 | 1.74¶ |

decedents with VTE were defined as those with VTE mentioned on their death certificates as contributing to their death;

overall OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.39–1.49; p<0.0001 for association between IPF and VTE compared with COPD and VTE.

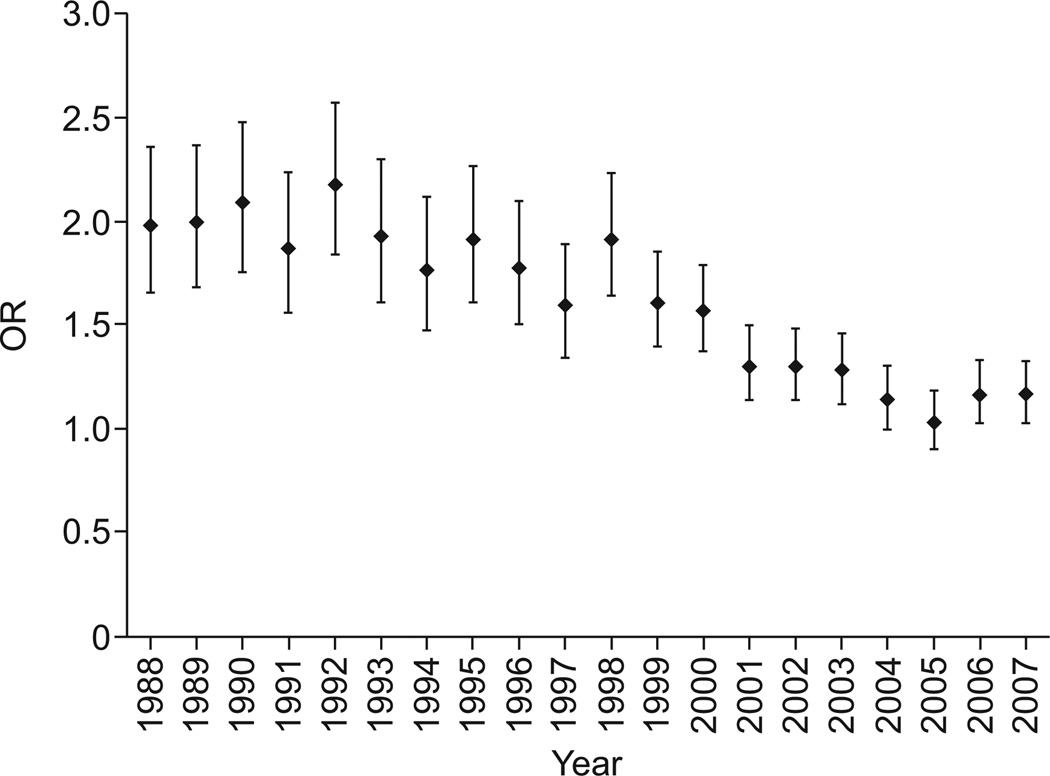

There were 3,233,845 decedents with lung cancer. Of these, 36,876 records also contained a code for VTE, yielding a prevalence of VTE that was significantly lower than for IPF (1.14% versus 1.74; p<0.0001) and a risk of VTE that was significantly greater in decedents with IPF (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.49–1.59) than in those with lung cancer (table 4). The risk of VTE was greater for IPF than lung cancer in every year except 2004 (p=0.53) and 2005 (p=0.65) (fig. 4). Using logistic regression and adjusting for age (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98–0.98), male sex (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.96–0.99) and year of death (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.04–1.04), the risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was found to be significantly greater than in those with lung cancer (adjusted OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.61–1.72).

TABLE 4.

Decedents with lung cancer or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and with and without venous thromboembolism (VTE)#

| Year | Lung cancer | IPF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | VTE absent n | VTE present n | VTE present % | |

| 1988 | 143813 | 1463 | 1.01 | 6762 | 136 | 1.97 |

| 1989 | 147379 | 1522 | 1.02 | 7321 | 151 | 2.02 |

| 1990 | 151442 | 1435 | 0.94 | 7432 | 147 | 1.94 |

| 1991 | 153958 | 1397 | 0.90 | 7839 | 133 | 1.67 |

| 1992 | 155896 | 1339 | 0.85 | 8240 | 154 | 1.83 |

| 1993 | 159031 | 1288 | 0.80 | 8661 | 135 | 1.53 |

| 1994 | 159542 | 1303 | 0.81 | 9086 | 131 | 1.42 |

| 1995 | 161091 | 1322 | 0.81 | 9494 | 149 | 1.55 |

| 1996 | 161790 | 1422 | 0.87 | 10059 | 157 | 1.54 |

| 1997 | 163112 | 1413 | 0.86 | 10719 | 148 | 1.36 |

| 1998 | 164794 | 1458 | 0.88 | 11210 | 190 | 1.67 |

| 1999 | 159765 | 1888 | 1.17 | 11585 | 220 | 1.86 |

| 2000 | 162813 | 2061 | 1.25 | 12347 | 245 | 1.95 |

| 2001 | 163088 | 2322 | 1.40 | 12664 | 235 | 1.82 |

| 2002 | 164647 | 2337 | 1.40 | 13268 | 245 | 1.81 |

| 2003 | 164747 | 2367 | 1.42 | 13639 | 251 | 1.81 |

| 2004 | 164452 | 2538 | 1.52 | 13572 | 239 | 1.73 |

| 2005 | 165793 | 2606 | 1.55 | 13736 | 223 | 1.60 |

| 2006 | 165002 | 2694 | 1.61 | 13686 | 261 | 1.87 |

| 2007 | 164814 | 2701 | 1.61 | 13856 | 265 | 1.88 |

| Total | 3196969 | 36876 | 1.14¶ | 215176 | 3815 | 1.74¶ |

decedents with VTE were defined as those with VTE mentioned on their death certificates as contributing to their death;

overall OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.49–1.59; p<0.0001 for association between IPF and VTE compared with lung cancer and VTE.

FIGURE 4.

The annual risk of venous thromboembolic disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when compared with lung cancer. The odds ratio (OR) was statistically significant (p<0.05) for all years except 2004 (p=0.53) and 2005 (p=0.65). Data are presented as OR with 95% CI.

Regardless of sex, decedents with IPF and VTE were significantly younger at the time of death than those with IPF but without VTE (females: 74.3 versus 77.4 yrs (p<0.0001); males: 72.0 versus 74.4 yrs (p<0.0001)). IPF decedents with VTE were more likely than those without VTE (73.2% versus 69.3%; p<0.0001) to have either VTE or IPF coded as the UCD. All other candidate conditions examined were less likely to be the UCD in the IPF decedents with VTE than in those without VTE (table 5).

TABLE 5.

The underlying cause of death (UCD) for decedents with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) with venous thromboembolism (VTE) or IPF alone over the entire study period#

| UCD | IPF with VTE¶ | IPF alone+ | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE and IPF | ||||

| VTE | 20.9 | |||

| IPF | 52.3 | 69.3 | 0.48 (0.45–0.51) | <0.0001 |

| Total | 73.2 | 69.3 | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac diseases | ||||

| Acute MI | 1.7 | 3.0 | 0.56 (0.46–0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease | 2.6 | 5.9 | 0.43 (0.35–0.53) | <0.0001 |

| CHF/cardiomyopathy | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.41 (0.29–0.59) | <0.0001 |

| Total | 5.2 | 10.9 | 0.45 (0.39–0.51) | <0.0001 |

| CVA/stroke | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.68 (0.48–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Infectious diseases | ||||

| Pneumonia | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.55 (0.41–0.73) | <0.0001 |

| Sepsis | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.56 (0.31–0.98) | 0.04 |

| Total | 1.6 | 2.8 | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 18.3 | 14.9 | 1.28 (1.18–1.39) | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as %, unless otherwise stated. International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes used for each category can be found in the Appendix. MI: myocardial infarction; CHF: congestive heart failure; CVA: cerebral vascular attack.

excluding lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

n=3,815;

n=215,176.

Compared with the background population, the overall risk of VTE was lower for those with lung cancer (1.14% versus 1.31%; OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.86–0.88) or COPD (1.22% versus 1.31%; OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.92–0.94). The risk of VTE was greater among decedents with COPD than those with lung cancer (lung cancer: 1.14% versus 1.22%; OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05–1.08).

DISCUSSION

Using mortality data from all USA decedents between 1988 and 2007, we found that the risk of VTE in those with IPF at the time of death was ≥34% higher than the risk of VTE in the background decedent population. We also found that the overall risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was 54% greater than for decedents with COPD and 44% greater than for decedents with lung cancer, two conditions previously identified to confer an increased risk of VTE [17–19].

Only a few studies have examined the relationship between VTE and IPF. Using primary care data from the UK from 1991–2003, Hubbard et al. [8] identified a cohort of 920 patients with IPF and found that, in comparison to the general population, the risk of deep-venous thrombosis was greater before (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.13–3.48) and even greater after (risk ratio 3.39, 95% CI 1.57–7.28) the diagnosis of IPF. Using hospital discharge and mortality data from 1980–2007, Sode et al. [9] examined the association between VTE and ILD in the entire Danish population. They found an increased risk for the development of ILD in people ever diagnosed with VTE, many of whom probably had IPF. In contrast to our study, they did not exclude subjects with known-cause PF, including those with conditions that might confound the relationship between VTE and PF (e.g. connective tissue diseases and obstetric conditions).

The risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was significantly greater than the background population for females >64 yrs of age and for males in every age group. In fact, male decedents with IPF appeared to be at particularly high risk of developing VTE. The reasons for these findings are unclear. Although younger females are in a pro-coagulant state and have an elevated risk of developing VTE due to hormonal influences from the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and contraceptives, we believe that in certain individuals, particularly beyond a certain age (apparently in males more than females), the fibrotic process confers an even more profound risk for VTE [20]. Although among all decedents in the USA from 1988–2007 the risk of VTE differed across race/ethnic groups, among those with IPF, the risk of VTE was not further affected by a decedent’s race or ethnicity.

Somewhat surprisingly, we found a significantly greater risk for VTE in IPF than either lung cancer or COPD. Using a case–control design, Blom et al. [21] studied subjects within a Dutch population and found a nearly 25-fold increased risk of VTE in patients with lung cancer when compared with controls. Levitan et al. [18] analysed a Medicare database and found that VTE occurred more frequently in lung cancer patients (6.1 events per 1,000 lung cancer patients) than in patients with various other malignancies. In another study, investigators observed that among patients who required hospital admission for an exacerbation of COPD, 25% had a pulmonary embolism [19]. Although the risk of VTE is elevated in patients with lung cancer, and emerging data suggest the same is true for certain patients with COPD, our results place IPF patients at even greater risk for mortal VTE events. The data leave little room for questioning the clinical significance of these VTE events: decedents with IPF and VTE died at a younger age than decedents with IPF alone, and in >20% of IPF decedents with VTE, VTE itself was the UCD.

We found that the risk of VTE in both decedents with lung cancer and those with COPD was significantly lower than the background population. There are several possible explanations for this observation: the first is that the background population indeed possessed a greater risk for mortality-related VTE than decedents with COPD or lung cancer; however, because the database did not allow us to determine the presence or absence of most VTE risk factors (i.e. hereditary causes and other acquired causes of thrombophilia including tobacco abuse) or VTE therapies (i.e. anticoagulation), we could not account for these potential confounders, in any of the subgroups, in our analyses. The data for the current study concern VTE events at the time of death; thus, we know nothing of the number, type, severity or treatment of VTE events that occurred earlier in the lives of people with COPD or lung cancer, or those in the background population. Our data should not be used to make inferences about life-long risk of VTE.

Not only is lung cancer a known risk for VTE, but once VTE is diagnosed in a patient with malignancy, current guidelines recommend that patients receive anticoagulation for life or until the malignancy has resolved [22]. This practice could reduce the rates of VTE at the time of death in patients with lung cancer. As more data emerge regarding the risk of VTE in patients with COPD, similar trends may ensue and, thus, may also explain the slightly, but significantly, higher risk of VTE in patient with COPD than lung cancer [19].

Finally, we suspect that in a great number of decedents with lung cancer, many conditions possibly contributing to death (e.g. VTE) do not get mentioned on death certificates: the underlying malignancy simply overshadows them, and death certifiers do not write them down. We suspect the same is true for decedents with COPD: at least historically, patients with COPD suffering a respiratory-related mortal event were overwhelmingly likely to have that event attributed to an acute exacerbation of COPD; perhaps an alternative cause (e.g. VTE) would not have even been investigated.

If this is true, why would IPF patients be at risk for developing VTE? Mounting evidence suggests that the IPF microenvironment is both pro-coagulant and antifibrinolytic, and that components of these haematological pathways contribute to the milieu that drives the fibrotic process [23]. In fact, pro-coagulant moieties (including elevated levels of protein C and reduced thrombomodulin) have been found in the systemic circulation of some patients with IPF during abrupt disease accelerations: so-called acute exacerbations [24]. These data suggest that IPF is a hypercoaguable state.

Recognising that IPF may be a hypercoaguable condition and that components of the coagulation cascade are either directly involved in or activated by fibrosis-producing machinery, Kubo et al. [25] tested the hypothesis that inhibiting the coagulation cascade would lead to improved outcomes in patients with IPF. They randomised 56 hospitalised Japanese patients with IPF to receive either prednisolone alone or prednisolone plus oral warfarin. Although the study did not meet its primary outcome, subjects receiving warfarin had a 3-yr survival of 63% compared with 35% for subjects receiving only prednisolone (p=0.04). In addition, when the authors examined acute exacerbations within this cohort, they found that the resultant mortality from an acute exacerbation (as well as d-dimer levels) was significantly lower in the group receiving warfarin therapy. IPFnet, a network of institutions in the USA sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and charged with conducting trials of therapy for IPF, is currently conducting a randomised, placebo-controlled trial of warfarin for the treatment of IPF.

Like other investigators using ICD-coded mortality data, we faced several limitations in this study. These were largely imposed by the dataset we chose to use. First, we had to rely on death certifiers to correctly identify cases and then code them appropriately. In some decedents with IPF (e.g. those whose IPF goes undiagnosed and those who are misdiagnosed as having some other lung disease), the correct diagnosis of IPF will not make it onto the death certificate. For these reasons, we believe, and others have previously demonstrated [3, 26], that PF is under-reported on death certificates. Furthermore, we could not assess the accuracy of a VTE diagnosis, and the modalities used to diagnose VTE are not captured in this dataset. Clinically significant VTE is probably under-reported when clinical criteria are used and probably over-reported when autopsy data are used [27]. Indeed, pulmonary emboli are commonly found at autopsy, and in 50–70% of cases, they were not suspected by the clinician [28]. If VTE was either under- or over-reported in this database, we would expect any such misclassification to be independent of whether a person had IPF or not, thus biasing the association toward the null. However, it remains possible that misreporting occurred: we have no way to determine this.

Acute exacerbations of IPF (AE-IPF) have only recently gained widespread recognition in the USA [29]. Given this, in the past, death certifiers could have labelled IPF patients who abruptly declined and died with VTE (pulmonary embolism), a reasonable potential explanation for acute decompensation and death. However, the year-by-year analysis in our study argues against this: decedents with IPF were more likely than decedents in the background population to have VTE in every year studied, including years since the entity AE-IPF first gained recognition in the USA. If, in more recent years, decedents were being “pulled” from the VTE-as-UCD group and placed in the IPF-as-UCD group, we would have expected a steady decline in VTE rates among IPF decedents; this was not the case.

The database restricted us from identifying risk factors for VTE, including the number of episodes of VTE any decedent had in his life, heritable hypercoaguable conditions, smoking status, and the use of oral contraceptives or female sex hormones. The fact that the association between IPF and VTE held in elderly females (a group perhaps less likely to be prescribed oral contraceptives) and in males argues strongly against any confounding by female sex hormone use.

In summary, using all death certificate records in the USA from 1988–2007, we found that the risk of VTE in decedents with IPF was significantly greater than in: 1) decedents in the background population, 2) those with lung cancer or 3) those with COPD. These findings add to a growing data pool on the links between pro-fibrotic and pro-coagulant pathways, but should be viewed as hypothesis generating. Nonetheless, we believe VTE should be considered in any IPF patient whose respiratory status is declining, particularly those in whom the decline is abrupt or no other cause can be identified. Research is needed to discern the interdependencies of the pro-fibrotic and pro-coagulant cascade, determine whether IPF induces a systemic hypercoaguable state, and discover whether therapeutic disruption of coagulation leads to improved outcomes in patients with IPF.

Acknowledgments

SUPPORT STATEMENT

J.J. Swigris is supported, in part, by a National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) Career Development Award (K23).

APPENDIX

Details of the ICD codes for excluded records

From 1988 to 1998, records were excluded if they contained ICD-9 codes for the following conditions: connective tissue disease or rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9 codes 710–710.9 and 714– 714.9), radiation fibrosis (ICD-9 code 508.1), asbestosis (ICD-9 code 501), coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (ICD-9 code 500), silicosis or talcosis (ICD-9 code 502), berylliosis and other inorganic dusts (ICD-9 code 503), unspecified pneumoconiosis (ICD-9 code 505), sarcoidosis (ICD-9 code 135), and/or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) (ICD-9 codes 495–495.9). After 1998, records were excluded if they contained an ICD-10 code for the following conditions: connective tissue disease or rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-10 codes M32–M35, M35.1, M35.5, M35.8, M35.9 and M36, or M05–M05.9, M06–M06.9 or M08–M08.9), radiation fibrosis (ICD-10 code J70.1), asbestosis (ICD-10 code J61), coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (ICD-10 code J60), silicosis or talcosis (ICD-10 codes J62–J62.8), berylliosis and other inorganic dusts (ICD-10 codes J63–J63.8), unspecified pneumoconiosis (ICD-10 codes J64–J65), sarcoidosis (ICD-10 codes D86–D86.9), and/or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) (ICD-10 codes D67–D67.9).

Details of the UCD classifications

From 1992 to 1998, the following ICD-9 codes were analysed to determine the UCD: ischaemic heart disease (ICD-9 codes 410– 414.9), heart failure (ICD-9 codes 428–428.9), pneumonia (ICD-9 codes 480–487.8) and cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9 codes 430–438). After 1998, the following ICD-10 codes were used to determine the underlying UCD: ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10 codes I20–I25), heart failure (ICD-10 codes I50–I50.9), pneumonia (ICD-10 codes J09–J18.9) and cerebrovascular disease (ICD-10 codes I60–I69.8).

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

Statements of interest for A. Fischer and J.J. Swigris can be found at www.erj.ersjournals.com/site/misc/statements.xhtml

REFERENCES

- 1.Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, et al. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:967–972. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston I, Britton J, Kinnear W, et al. Rising mortality from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. BMJ. 1990;301:1017–1021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6759.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard R, Johnston I, Coultas DB, et al. Mortality rates from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in seven countries. Thorax. 1996;51:711–716. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.7.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mannino DM, Etzel RA, Parrish RG. Pulmonary fibrosis deaths in the United States, 1979–1991: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1548–1552. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Lezotte DC, et al. Mortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:277–284. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-044OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646–664. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.ats3-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard RB, Smith C, Le Jeune I, et al. The association between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and vascular disease: a population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1257–1261. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-725OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sode BF, Dahl M, Nielsen SF, et al. Venous thromboembolism and risk of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: a nationwide study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1085–1092. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imokawa S, Sato A, Hayakawa H, et al. Tissue factor expression and fibrin deposition in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and systemic sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:631–636. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9608094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi H, Gabazza EC, Taguchi O, et al. Protein C anticoagulant system in patients with interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1850–1854. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9709078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olman MA, Mackman N, Gladson CL, et al. Changes in procoagulant and fibrinolytic gene expression during bleomycin-induced lung injury in the mouse. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1621–1630. doi: 10.1172/JCI118201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Use Data Tape Documentation: Multiple Cause of Death for ICD-9 1992 Data. Hyattsville: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1994. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Simon P. A comparison of underlying cause and multiple causes of death. Epidemiology. 2006;17:100–103. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000187177.96138.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Public Health Service. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision. Dept of Health and Human Services Publication No. (PHS) 80-1260. Washington: US Government Printing Office; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesselaar ME, Osanto S. Risk of venous thromboembolism in lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:362–367. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328209413c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levitan N, Dowlati A, Remick S, et al. Rates of initial and recurrent thromboembolic disease among patients with malignancy versus those without malignancy: risk analysis using Medicare claims data. Medicine. 1999;78:285–291. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizkallah J, Man SF, Sin DD. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2009;135:786–793. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trigg DE, Wood MG, Kouides PA, et al. Hormonal influences on hemostasis in women. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:77–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, et al. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293:715–722. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(Suppl 6):454S–545S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers RC. Procoagulant signaling mechanisms in lung inflammation and fibrosis: novel opportunities for pharmacological intervention? Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S367–S378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collard H, Calfee CS, Wolters PJ, et al. Plasma biomarker profiles in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L3–L7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90637.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubo H, Nakayama K, Yanai M, et al. Anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005;128:1475–1482. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coultas DB, Hughes MP. Accuracy of mortality data for interstitial lung diseases in New Mexico, USA. Thorax. 1996;51:717–720. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.7.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(Suppl 1):I4–I8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein PD, Henry JW. Prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism among patients in a general hospital at autopsy. Chest. 1995;108:978–981. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:636–640. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]