Abstract

Purpose:

To report the feasibility and outcome of lens aspiration, and Fugo blade-assisted capsulotomy and anterior vitrectomy in eyes with anterior persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV).

Materials and Methods:

In this case series, 10 eyes of 10 patients with anterior PHPV underwent lens aspiration. The vascularized posterior capsule was cut with a Fugo blade (plasma knife) and removed with a vitrector. A foldable posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) was implanted in eight eyes and the outcomes were evaluated.

Results:

The mean age of patients was 16.8 ± 6.37 months (range: 5 to 28 months). The surgery was completed successfully in all eyes. There were no cases of intraocular hemorrhage intraoperatively. Foldable acrylic IOL was implanted in the bag in 3 eyes and in the sulcus in 5 eyes. Two eyes were microphthalmic and did no undergo IOL implantation (aphakic). None of the eyes had a significant reaction or elevated intraocular pressure postoperatively. The follow-up ranged from 4 to 21 months. All the pseudophakic eyes achieved a best corrected visual acuity of ≥20/200 with 50% (4/8) of these eyes with ≥20/60 vision.

Conclusion:

Lens aspiration followed by posterior capsulotomy with Fugo blade-assisted plasma ablation is a feasible technique for performing successful lens surgery in cases with florid anterior PHPV.

Keywords: Fugo Blade, Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous, Plasma Knife

INTRODUCTION

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV) is a congenital developmental anomaly of the eye due to failure of embryological primary vitreous and hyaloid vasculature to regress. PHPV usually presents in an otherwise healthy newborn, and the clinical ocular manifestations include microphthalmia, progressive cataract, retrolental fibrovascular tissue, persistent hyaloid vessel remnants and tunica vasculosa lentis remnants. Surgery for PHPV is complicated due to the high risk of bleeding from the vascularized membrane and the stalk, which can cause vitreous hemorrhage or hyphema during the postoperative period. Variable visual and anatomical outcomes have been reported in a surgical series of eyes with PHPV.1,2,3,4,5

The Fugo plasma blade (MediSurg Research and Management Corp., Norristown, PA, USA) has recently been approved for performing capsulotomies, iridotomies and transciliary filtration.6,7,8,9,10,11 The Fugo Blade tip comes in different lengths and can be bent as required. Only the extreme tip gets activated for cutting. An electronic charge pump causes the upper layer of atoms in the filament (about a micron deep) to transform from the solid state into the activated plasma state. Plasma blade uses pulses of plasma that are generated around the tip to cut and cauterize tissue without extensive collateral tissue damage.

We performed this study to evaluate the feasibility and outcome of lens aspiration, and posterior capsulotomy by Fugo blade-assisted plasma ablation and anterior vitrectomy in eyes with anterior PHPV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed in 10 eyes of 10 patients with anterior PHPV [Figure 1a]. All patients were enrolled from the outpatient department of the Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. The parents of the children underwent a thorough discussion of the condition including the guarded visual prognosis, and an informed written parental consent was obtained in all cases. The study was registered with the institutional review board and an approval was obtained from ethics committee. A detailed evaluation of the cornea and anterior segment was performed under anesthesia, including measurement of corneal diameter, and keratometry. Axial length was measured and the posterior segment was evaluated with ultrasonography. The presence of anterior PHPV was confirmed by direct visualization of the vascularized membrane if the cataract was not very dense and by imaging of the stump behind the posterior capsule by B-scan ultrasonography. Cases of anterior PHPV were only included, and eyes with features indicative of posterior PHPV i.e. presence of a stalk extending from the back of the crystalline lens up to the optic nerve head were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

(a) Cataract with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous; (b) Vascularized membrane after lens aspiration; (c) Fugo blade-assisted membranectomy; (d) Implantation of intraocular lens; (e) Clinical picture at 1 year follow-up

The surgeries were performed under general anesthesia by one surgeon (RS) involved in the study. A clear corneal tunnel and two side ports were created. After complete aspiration of the lens matter, the vascularized membrane was clearly visible [Figure 1b]. The anterior chamber was reformed with viscoelastic. The Fugo blade (plasma knife) was introduced into the anterior chamber and the vascularized posterior capsule was cut [Figure 1c] in a circular fashion in the cutting mode with a cut intensity of 3.5 in order to create a posterior capsular opening of nearly 5.0 mm. The stump behind the posterior capsule was coagulated slightly distal to the tip in the cutting mode and with a cut intensity of 4. This provides hemostasis and prevents traction to the retina when the fibrovascular membrane is removed with bimanual vitrectomy. A foldable acrylic intraocular lens was implanted [Figure 1d] in the bag. An IOL was implanted only in eyes with an axial length greater than 18 mm. The corneal tunnel was closed with a single 10-0 monofilament nylon suture. The postoperative treatment included 0.5% moxifloxacin eye drops TID [Vigamox; Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA] and 1% prednisolone acetate eye drops QID [Pred forte; Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA] for 4 weeks and 1% tropicamide eye drops TID for 2 weeks.

Postoperative examinations were performed at day 1, 1 week, 4 weeks, 3 months and 6 months and every 6 months thereafter. Examination under anesthesia was performed at 1 and 3 months. The parameters evaluated were the status of the anterior segment, IOL centration, quality of fundus reflex i.e. a uniform red reflex or an opacity with funduscopy, refraction, status of the posterior segment and intraocular pressure. The best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was recorded with Cardiff/Teller acuity cards at 3 months postoperatively.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 16.8 ± 6.37 months (range: 5 months to 28 months). Of the 10 patients, 6 were males and 4 were females. All the patients had anterior PHPV with no evidence of posterior PHPV as discussed above.

All eyes underwent successful lens aspiration, posterior capsulotomy and anterior vitrectomy. There were no cases of intraocular hemorrhage intraoperatively. An IOL was implanted in 8 of 10 eyes. A single piece foldable acrylic IOL with a 6.0 mm optic (SA60AT, Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) was implanted in the capsular bag in 3 eyes and a multi-piece foldable acrylic IOL with a 6.0 mm optic (MA60AC; Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) was implanted in the ciliary sulcus in 5 eyes. Two eyes were left aphakic due to microphthalmia.

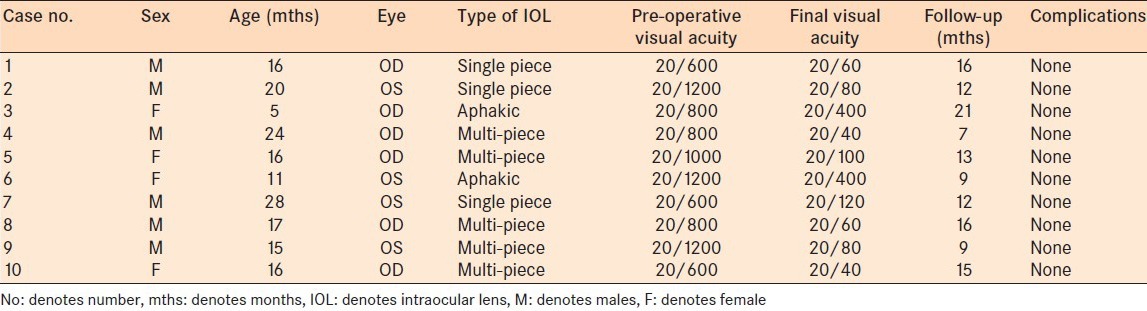

Follow-up ranged from 7 months to 21 months postoperatively. The IOL was well centered in all eyes [Figure 1e] at the last follow-up visit. None of the eyes showed significant anterior chamber reaction or elevated intraocular pressure postoperatively. All the patients underwent amblyopia therapy. The postoperative BCVA in all the pseudophakic eyes was >20/200. The BCVA was ≥20/60 in 4 of these eyes. The two microphthalmic eyes there were left aphakic had BCVA of 20/400 [Table 1]. None of the eyes had any significant complications requiring a second intervention during the follow-up period.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

DISCUSSION

Indications for surgical intervention in PHPV have changed over the years as knowledge of the disease and surgical instrumentation advanced. The decision to operate depends on a variety of factors such as the severity of the disease, the patient's age and the visual prognosis. Surgical treatment may not be effective in patients with severe microphthalmia or advanced posterior persistent fetal vasculature, such as marked foveal hypoplasia, dysplasia or retinal detachment.12 However, the absence of posterior segment involvement is predictive of better vision in these cases.5 Pollard13,14 found that anterior PHPV is occasionally associated with a good visual outcome when adequate treatment is provided. Such outcome can be predicted more accurately if treatment is provided before cataract develops because the treatment usually prevents the development of glaucoma and amblyopia.

Intraoperative hemorrhage is one of the important complications in PHPV eyes undergoing surgery. The extent of hemorrhage at any stage may prevent further continuation of the procedure. This, in our experience, may force a surgeon to abandon the surgery in such cases (unpublished data). Intraoperative vitreous hemorrhage has also been reported in some cases operated for PHPV.15 The technique for a plasma blade for PHPV has been previously described.16 We evaluated the safety, feasibility and outcome of this technique in cases of anterior PHPV in our case series.

The plasma knife (Fugo blade) is a radiofrequency electrosurgical incising instrument that uses electromagnetic energy to perform cutting and provides non-cauterizing hemostasis called “autostasis”.6 The instrument functions as a sharp and precise cutting tool allowing the surgeon to construct a round capsulotomy without tearing and stretching the capsule.7,8 It has also been used for transciliary filtration,9 construction of corneal incisions10 and enlargement of anterior phimotic capsulorhexis.11 In our study, we used the plasma knife to cut the vascularized posterior capsule and the retrolental stump in eyes with anterior PHPV, and none of the eyes had a hemorrhage during the intraoperative and postoperative periods.

In the past, lensectomy combined with anterior vitrectomy has been the surgical option of choice for management of cases with PHPV. Variable results have been reported. Pollard12 reported that 17% of the patients achieved a final visual acuity of 20/100 or better after surgery and amblyopia therapy. Dass et al.3 performed lensectomy and vitrectomy in these cases and reported that 17% of the cases achieved a final visual acuity of 20/800 or better. In another study, it was noted that 47% of cases achieved a final visual acuity of 20/400 or better after lensectomy and vitrectomy.4 Hunt et al.5 also reported the results of lensectomy and vitrectomy in cases with PHPV and noted that only 18% of eyes achieved 6/60 or better at the final follow-up visit of 28 months. All of these cases were rehabilitated with aphakic contact lenses or spectacles postoperatively. However, recent studies have documented better outcomes in pseudophakic eyes in such cases. Anteby et al.17 noted that a visual acuity of 20/60 or better in 17% of aphakic eyes and 33% of pseudophakic eyes, the difference being statistically significant. Similar results were seen in another recent study that concluded that early primary IOL implantation in cases with PHPV yields satisfactory functional results.18 In our case series, all the pseudophakic eyes achieved a BCVA of at least 20/200 and 50% had a vision equal to or better than 20/60.

We strongly believe that there is significant role for the Fugo blade in cases undergoing lens surgery for florid anterior PHPV as it allows successful completion of surgery without significant intraocular hemorrhage. The utility of the plasma knife may aid a surgeon to successfully operate cases with PHPV, which are sometimes deemed inoperable. Additionally, the procedure may allow a surgeon to implant an IOL in the posterior chamber, which may translate into better functional outcomes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roussat B, Barbat V, Cantaloube C, Baz P, Iba-Zizen MT, Hamard H. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous syndrome: Clinical and therapeutic aspects. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1998;21:501–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollard ZF. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous: diagnosis, treatment and results. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;95:487–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dass AB, Trese MT. Surgical results of persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:280–4. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrakis G, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr, Murray TG, Feuer WJ. Visual acuity outcomes with and without surgery in patients with persistent fetal vasculature. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1068–72. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt A, Rowe N, Lam A, Martin F. Outcomes in persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:859–63. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.053595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fugo RJ, Delcampo DM. The Fugo Blade: The next step after capsulorhexis. Ann Ophthalmol. 2001;33:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izak AM, Werner L, Pandey SK, Apple DJ, Izak MG. Analysis of the capsule edge after Fugo plasma blade capsulotomy, continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, and can-opener capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:2606–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson M. Anterior lens capsule management in pediatric cataract surgery. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;2:391–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh D, Bundela R, Agarwal A, Bist HK, Satsangi SK. Goniotomy ab interno “a glaucoma filtering surgery” using the Fugo Plasma Blade. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie) 2006;38:213–7. doi: 10.1007/s12009-006-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peponis V, Rosenberg P, Reddy SV, Herz JB, Kaufman HE. The use of the Fugo Blade in corneal surgery: A preliminary animal study. Cornea. 2006;25:206–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000179927.12899.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fugo R. Fugo Blade to enlarge phimotic capsulorhexis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1900. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng LS, Kuo HK, Lin SA, Kuo ML. Surgical results of persistent fetal vasculature. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:602–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollard ZF. Results of treatment of persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollard ZF. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous: diagnosis, treatment and results. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;95:487–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundvall A, Zetterström C. Primary intraocular lens implantation in infants: Complications and visual results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1672–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khokhar S, Tejwani LK, Kumar G, Kushmesh R. Approach to cataract with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1382–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anteby I, Cohen E, Karshai I, BenEzra D. Unilateral persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous: Course and outcome. J AAPOS. 2002;6:92–9. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.121324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidullin IS, Aznabaev RA. Primary artificial lens implantation in young children with the primary hyperplastic vitreous body. Vestn Oftalmol. 2008;124:44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]