Abstract

Purpose:

To describe a loop suture technique that allows intraoperative conjunctival closure and later optional suture adjustment in strabismus surgery in uncooperative patients.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective case series comprised 25 patients. After a recessed or resected horizontal muscle was secured to the sclera with a primary suture suspended back 2 mm, a second loop suture was passed through the body of the muscle and under the primary suture knot. The loop suture could be removed later while the patient was awake, or it could be tied to advance the muscle. Success was defined as a residual deviation of 10 prism diopters (PD) or less at 2 months postoperatively.

Results:

In the study cohort, 20 patients had successful alignment at 2 months (80%). Six patients (24%) underwent postoperative suture tightening by the loop technique, and each muscle affected the alignment an average of 7.7 PD (±3.8 PD). No patients underwent a reoperation within the first 2 months. One patient had a pyogenic granuloma (4%).

Conclusions:

The loop suture technique permits optional postoperative tightening of muscles and avoids sedation in children or uncooperative patients not requiring adjustment.

Keywords: Adjustable Suture, Esotropia, Exotropia, Strabismus Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Adjustable sutures are used in strabismus surgery to refine eye alignment in the immediate postoperative period. Retrospective case series generally indicate better outcomes with adjustable sutures.1,2,3,4 To our knowledge, a small randomized controlled trial of adjustable versus conventional sutures has been performed.5 For exotropia, adjustable sutures improved the frequency of success (defined as within 8 prism diopters [PD] of orthotropia) at 3 months in 22 of 30 patient (73%) compared with eight of 15 patients with conventional sutures (53%).5 Nonetheless, adjustable sutures have not gained universal acceptance,3 due to the lack of large randomized clinical trials,3,6 the prolonged surgical learning curve,3 the extra time required in the operating room, the potential for patient discomfort during adjustment, the increased potential for slipped muscles,7 and the difficulty of adjustments in awake, but uncooperative patients, including children.2,8 For standard adjustable suture techniques, even when successful alignment makes adjustment unnecessary, manipulation is required to permanently tighten the knot, a traction suture is removed if used, and finally the conjunctiva is closed.1,2,3 In uncooperative patients, such as young children, these steps usually require sedation.2 Jampolsky, et al. in describing their adjustable suture technique stated, “Our youngest patient was 9 years old,… however, most children under 14 are unable to cooperate for the adjustment.”9

Coats described a ripcord technique in which a one-time, single stage loosening of the muscle can be performed in a minimally cooperative patient.8 Kushner reviewed a semi-adjustable technique in which tightening of the center of the muscle belly is achieved with a second suture passed through the sclera anteriorly.7 Both of these techniques require additional scleral passes of the suture.7,8 Additionally, the semi-adjustable technique also requires postoperative tying and cutting of the central muscle suture, even if ocular alignment is acceptable.7

Several groups have described short tag noose adjustable sutures that do not require manipulation when adjustment is unnecessary.10,11 Sometimes, a traction suture is necessary, and rarely the noose can spontaneously slip.10,11 Adjustment of both the ripcord and short tag noose techniques require careful manipulation of the conjunctiva to provide substantial exposure, to avoid cutting the incorrect suture in the former case, and to precisely adjust the suture in the latter case. Both techniques leave extra subconjunctival suture material in patients not requiring adjustment, which might increase the rate of pyogenic granuloma. To address these limitations, we developed a quick and easy one-step, preprogrammed adjustment suture technique for uncooperative patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective chart review was approved by the human subjects committees at our hospitals. All patients having their first horizontal muscle strabismus surgery at either hospital from September 2008 to March 2010 who had loop suture placement were analyzed for age, diagnosis, preoperative alignment, postoperative alignment, and complications. Success was defined as residual deviation of 10 PD or less at 2 months.4,10,11 All surgeries were under general anesthesia with a fornix conjunctival incision, and the horizontal muscles were secured using a double-armed 6-0 polyglactin absorbable suture (Vicryl S-14; Ethicon Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, New Jersey). After muscle recession or resection, the conjunctiva was closed in the operating room with interrupted 6-0 absorbable plain gut suture, with the loop suture passing through the original fornix incision.

Recession

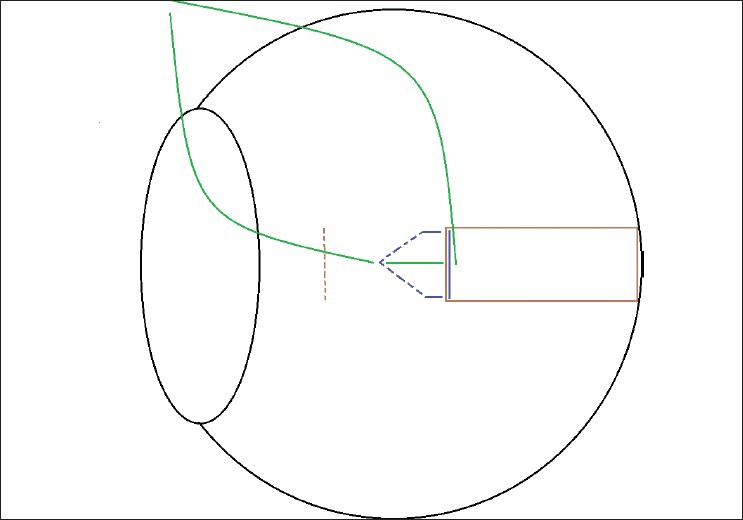

The muscle was secured using a double-armed suture and was disinserted. The spatulated needles of this primary suture were passed in a “V” configuration through the sclera and the suture ends were secured into a knot, with the muscle suspended (“hanging back”) 2 mm to lie at the desired recession position [Figure 1]. One of the suture ends was cut, and its needle was passed through the muscle belly posterior to the primary suture and then between the primary suture knot and the sclera, to produce the “loop” suture [Figure 1]. The loop suture ends were temporarily pulled together to measure in mm, the degree to which tightening would advance the muscle. The ends of the loop suture were tied.

Figure 1.

Schematic of loop adjustable suture for rectus muscle recession. Rectus muscle (solid) and original insertion (dotted) in brown. Primary suture in blue (Passes through sclera are dotted). Adjustable loop suture in green

Temporarily pulling together the loop suture ends permitted visual confirmation that the entire muscle belly continued to lay flat as it advanced, because the primary suture knot was able to move posteriorly to meet the advancing central muscle belly. This posterior movement of the primary suture knot equalized tension of the central and peripheral primary suture, so that the muscle center and edges advanced in tandem. This characteristic differs from that of the previously-described semi-adjustable suture, which advances the center of the muscle but not the muscle periphery.7

Resection

The muscle was secured using a double-armed suture placed at the desired resection distance plus 2 mm, and was then resected. The spatulated needles of this primary suture were passed in a “V” configuration through the sclera at the original muscle insertion, and the suture ends were secured into a knot, with the muscle suspended (“hanging back”) 2 mm. The loop suture was placed as described above.

Postoperative adjustment

In the postoperative recovery area, binocular alignment was assessed 1 h after surgery by the alternative cover test with a distant target (at 20 feet), and the loop suture knot was cut. If alignment was acceptable, the loop suture was simply removed under topical anesthesia. If suture tightening was required, the anesthesiologist provided intravenous sedation for extremely uncooperative patients (young children and the mentally disabled). The loop suture was tied tight to advance the muscle, and its ends were cut short. It might be possible to partially advance the muscle (less than the full 2 mm), although we did not attempt to do so.

RESULTS

The adjustable suture technique was performed on 25 patients. The age of the patients ranged from 16 months to 83 years. There were 18 adults and seven children (all aged 11 and under). The four patients age six or under included a 16 month old and a 17 month old. In addition to the seven children, we suspected that four patients might be uncooperative with suture adjustment due to traumatic brain injury (n = 3), or due to a history of poor cooperation after a traumatic injury (n = 1). The 14 procedures for exotropia included one case of third cranial nerve palsy. The 11 procedures for esotropia included four cases of sixth nerve palsy and one case of accommodative esotropia. Three patients had previous strabismus surgery. Four patients were legally blind in one eye. There were no cases of Graves’ disease or Duane syndrome. The number of patients having 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-muscle surgery was 4, 16, 2, and 3, respectively. Patients had the loop suture placed on recessed muscles only (n = 17), on resected muscles only (n = 1), or on both recessed and resected muscles (n = 7).

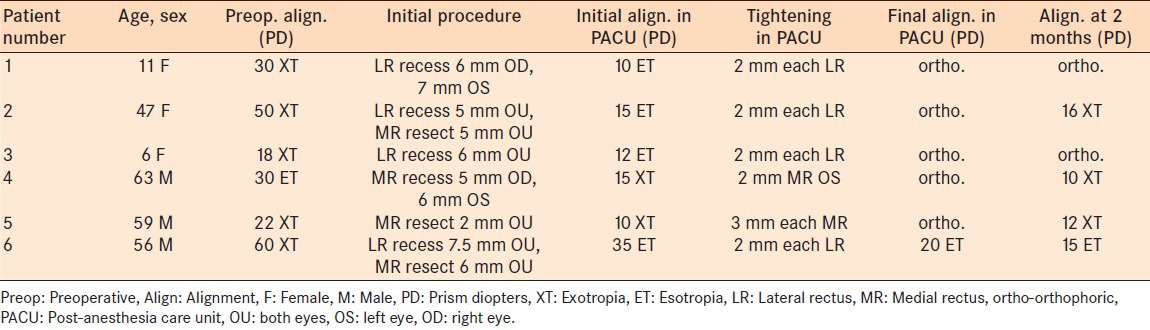

In the six patients (24%) who underwent postoperative suture tightening by the loop technique in the postoperative recovery area, each muscle tightened affected the alignment by about 7.7 PD [SD 3.8 PD, n = 6 patients, Table 1]. For patient five, the muscles hung back 3 mm intraoperatively, instead of the target of 2 mm, which meant that in the post-anesthesia care unit, a 3 mm tightening of each muscle was observed.

Table 1.

Primary position alignment in six patients undergoing suture adjustment

In the two children (but not the four adults), the anesthesiologist provided sedation with low-dose propofol during tightening of the loop. One child moved during the procedure because the sedation was incomplete. Nonetheless, it was still possible to tighten the loop.

In the patients who did not require loop tightening (n = 19), the loop was removed with topical anesthesia, and no sedation. This group included five of the seven children, and all four additional patients expected preoperatively to be uncooperative.

At the 2 month postoperative visit, 20 out of the 25 patients (80%) had <10 PD of residual misalignment. One pediatric and four adult patients remained with greater than 10 PD of misalignment. Five patients reported diplopia, although three of them met the criteria for successful alignment. Of the five patients with >10 PD of misalignment, two reported diplopia and three had a postoperative suture adjustment. Of the six patients who underwent a postoperative suture adjustment, three met the criteria for a successful result. Of the 19 patients who did not require adjustment, 17 met the criteria for success. One patient developed a pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Adjustable sutures were developed to improve alignment and reduce the reoperation rate after strabismus surgery. Unfortunately, traditional adjustable sutures require a cooperative patient or additional sedation after assessment of binocular alignment. We have demonstrated a very simple suture adjustment technique for uncooperative patients.

The best comparison might be with nonadjustable sutures, which are still widely used in uncooperative patients. After assessing the alignment postoperatively, the surgeon has the option of simply removing the loop suture under topical anesthesia, to convert the operation to a conventional nonadjustable suture. It is logical to believe that the option to tighten the suture would improve the success rate, and one loses very little time by giving oneself this option. This success rate of 80% in this small series, using a previous definition of success,4,10,11 is similar to the 75%,4 81%,10 and 84%11 rates reported previously with adjustable sutures. As the loop technique does not require substantial retraction of the conjunctiva to expose the sutures, the conjunctiva may be closed intraoperatively, and minimal patient cooperation is required for adjustment. We acknowledge that not all surgeons routinely suture the conjunctiva, but the lack of need for conjunctival retraction to expose the muscle suture postoperatively is still an advantage of the loop suture technique.

In 76% of patients who did not require an adjustment, the loop was removed using topical anesthesia. This ability contrasts with standard adjustable or semi-adjustable sutures, which require repeat sedation in all uncooperative patients, such as young children, even if adjustment is not needed (to permit suture tying and cutting, traction suture removal, and conjunctival closure).2,7

Tightening of the loop was so simple that it was accomplished even when a child moved due to incomplete sedation. Standard adjustment techniques would not have been possible in this case.

The single pyogenic granuloma could not have been due to the loop suture, because it had been removed without tightening in the recovery area.

The loop technique has only been evaluated on horizontal muscles, and has limitations. The postoperative adjustment resolves only small amounts of residual misalignment (on average 7 PD per muscle). While the ripcord adjustment only permits loosening of the muscle,8 our adjustment technique, like the semi-adjustable technique,7 only permits tightening of the muscle. In conclusion, our loop suture technique is useful for optional postoperative adjustment, especially in uncooperative patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wisnicki HJ, Repka MX, Guyton DL. Reoperation rate in adjustable strabismus surgery. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1988;25:112–4. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19880501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awadein A, Sharma M, Bazemore MG, Saeed HA, Guyton DL. Adjustable suture strabismus surgery in infants and children. J AAPOS. 2008;12:585–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nihalani BR, Hunter DG. Adjustable suture strabismus surgery. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1262–76. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang MS, Hutchinson AK, Drack AV, Cleveland J, Lambert SR. Improved ocular alignment with adjustable sutures in adults undergoing strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Julka A, Gadia R, Chhabra A, Dehran M. Evaluation of single-stage adjustable strabismus surgery under conscious sedation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:121–5. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.45501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundaram V, Haridas A. Adjustable versus non-adjustable sutures for strabismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD004240. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004240.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushner BJ. An evaluation of the semiadjustable suture strabismus surgical procedure. J AAPOS. 2004;8:481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coats DK. Ripcord adjustable suture technique for use in strabismus surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1364–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.9.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jampolsky A. Current techniques of adjustable strabismus surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88:406–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90641-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nihalani BR, Whitman MC, Salgado CM, Loudon SE, Hunter DG. Short tag noose technique for optional and late suture adjustment in strabismus surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budning AS, Day C, Nguyen A. The short adjustable suture. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45:359–62. doi: 10.3129/i10-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]