Abstract

The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is the major regulator of cytoprotective responses to oxidative and electrophilic stress. Although cell signaling pathways triggered by the transcription factor Nrf2 prevent cancer initiation and progression in normal and premalignant tissues, in fully malignant cells Nrf2 activity provides growth advantage by increasing cancer chemoresistance and enhancing tumor cell growth. In this graphical review, we provide an overview of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway and its dysregulation in cancer cells. We also briefly summarize the consequences of constitutive Nrf2 activation in cancer cells and how this can be exploited in cancer gene therapy.

Keywords: Nrf2, Keap1, Cancer, Antioxidant response element, Gene therapy

Introduction

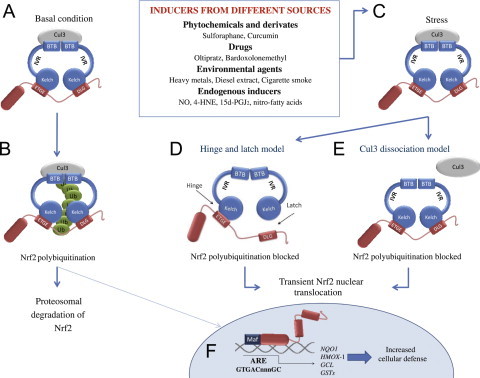

The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is the major regulator of cytoprotective responses to endogenous and exogenous stresses caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and electrophiles [1]. The key signaling proteins within the pathway are the transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) that binds together with small Maf proteins to the antioxidant response element (ARE) in the regulatory regions of target genes, and Keap1 (Kelch ECH associating protein 1), a repressor protein that binds to Nrf2 and promotes its degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (Fig. 1). Keap1 is a very cysteine-rich protein, mouse Keap1 having a total of 25 and human 27 cysteine residues, most of which can be modified in vitro by different oxidants and electrophiles [2]. Three of these residues, C151, C273 and C288, have been shown to play a functional role by altering the conformation of Keap1 leading to nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and subsequent target gene expression [3] (Fig. 1). The exact mechanism whereby cysteine modifications in Keap1 lead to Nrf2 activation is not known, but the two prevailing but not mutually exclusive models are (1) the “hinge and latch” model, in which Keap1 modifications in thiol residues residing in the IVR of Keap1 disrupt the interaction with Nrf2 causing a misalignment of the lysine residues within Nrf2 that can no longer be polyubiquitinylated and (2) the model in which thiol modification causes dissociation of Cul3 from Keap1 [3]. In both models, the inducer-modified and Nrf2-bound Keap1 is inactivated and, consequently, newly synthesized Nrf2 proteins bypass Keap1 and translocate into the nucleus, bind to the ARE and drive the expression of Nrf2 target genes such as NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1), glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione S transferases (GSTs) (Fig. 2). In addition to modifications of Keap1 thiols resulting in Nrf2 target gene induction, proteins such as p21 and p62 can bind to Nrf2 or Keap1 thereby disrupting the interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1 [1,3] (Fig. 3).

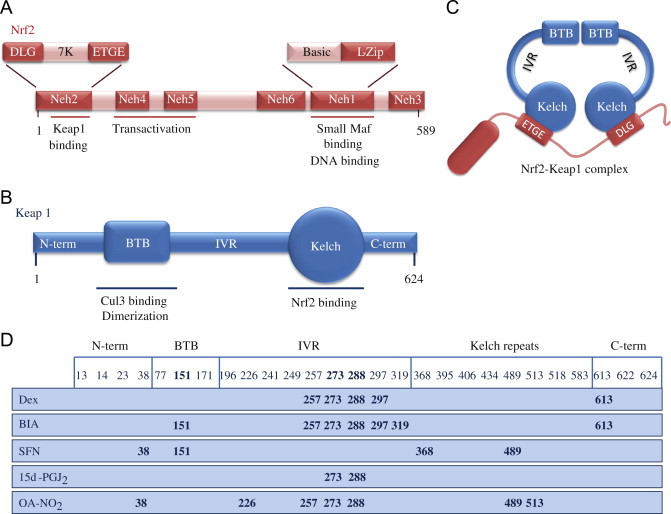

Fig. 1.

Structures of Nrf2 and Keap1 and the cysteine code. (A) Nrf2 consists of 589 amino acids and has six evolutionarily highly conserved domains, Neh1-6. Neh1 contains a bZip motif, a basic region – leucine zipper (L-Zip) structure, where the basic region is responsible for DNA recognition and the L-Zip mediates dimerization with small Maf proteins. Neh6 functions as a degron to mediate degradation of Nrf2 in the nucleus. Neh4 and 5 are transactivation domains. Neh2 contains ETGE and DLG motifs, which are required for the interaction with Keap1, and a hydrophilic region of lysine residues (7 K), which are indispensable for the Keap1-dependent polyubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2. (B) Keap1 consists of 624 amino acid residues and has five domains. The two protein–protein interaction motifs, the BTB domain and the Kelch domain, are separated by the intervening region (IVR). The BTB domain together with the N-terminal portion of the IVR mediates homodimerization of Keap1 and binding with Cullin3 (Cul3). The Kelch domain and the C-terminal region mediate the interaction with Neh2. (C) Nrf2 interacts with two molecules of Keap1 through its Neh2 ETGE and DLG motifs. Both ETGE and DLG bind to similar sites on the bottom surface of the Keap1 Kelch motif. (D) Keap1 is rich in cysteine residues, with 27 cysteines in human protein. Some of these cysteines are located near basic residues and are therefore excellent targets of electrophiles and oxidants. The modification pattern of the cysteine residues by electrophiles is known as the cysteine code. The cysteine code hypothesis proposes that structurally different Nrf2 activating agents affect different Keap1 cysteines. The cysteine modifications lead to conformational changes in the Keap1 disrupting the interaction between the Nrf2 DLG and Keap1 Kelch domains, thus inhibiting the polyubiquitination of Nrf2. The functional importance of Cys151, Cys273 and Cys288 has been shown, as Cys273 and Cys288 are required for suppression of Nrf2 and Cys151 for activation of Nrf2 by inducers [1,3].

Fig. 2.

The Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway. (A and B) in basal conditions, two Keap1 molecules bind to Nrf2 and Nrf2 is polyubiquitylated by the Cul3-based E3 ligase complex. This polyubiquitilation results in rapid Nrf2 degradation by the proteasome. A small proportion of Nrf2 escapes the inhibitory complex and accumulates in the nucleus to mediate basal ARE-dependent gene expression, thereby maintaining the cellular homeostasis. (C) Under stress conditions, inducers modify the Keap1 cysteines leading to the inhibition of Nrf2 ubiquitylation via dissociation of the inhibitory complex. (D) According to the hinge and latch model, modification of specific Keap1 cysteine residues leads to conformational changes in Keap1 resulting in the detachment of the Nrf2 DLG motif from Keap1. Ubiquitination of Nrf2 is disrupted but the binding with the ETGE motif remains. (E) In the Keap1-Cul3 dissociation model, the binding of Keap1 and Cul3 is disrupted in response to electrophiles, leading to the escape of Nrf2 from the ubiquitination system. In both of the suggested models, the inducer-modified and Nrf2-bound Keap1 is inactivated and, consequently, newly synthesized Nrf2 proteins bypass Keap1 and translocate into the nucleus, bind to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) and drive the expression of Nrf2 target genes such as NQO1, HMOX1, GCL and GSTs [1,3].

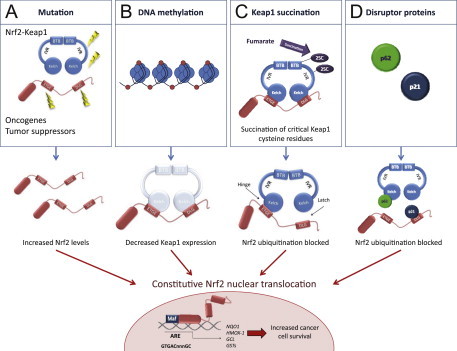

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms for constitutive nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 in cancer. (A) Somatic mutations in Nrf2 or Keap1 disrupt the interaction of these two proteins. In Nrf2, mutations affect ETGE and DLG motifs, but in Keap1 mutations are more evenly distributed. Furthermore, oncogene activation, such as KrasG12D[5], or disruption of tumor suppressors, such as PTEN [11] can lead to transcriptional induction of Nrf2 and an increase in nuclear Nrf2. (B) Hypermethylation of the Keap1 promoter in lung and prostate cancer leads to reduction of Keap1 mRNA expression, which increases the nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 [6,7]. (C) In familial papillary renal carcinoma, the loss of fumarate hydratase enzyme activity leads to the accumulation of fumarate and further to succination of Keap1 cysteine residues (2SC). This post-translational modification leads to the disruption of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction and nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 [8,9]. (D) Accumulation of disruptor proteins such as p62 and p21 can disturb Nrf2-Keap1 binding and results in an increase in nuclear Nrf2. p62 binds to Keap1 overlapping the binding pocket for Nrf2 and p21 directly interacts with the DLG and ETGE motifs of Nrf2, thereby competing with Keap1 [10].

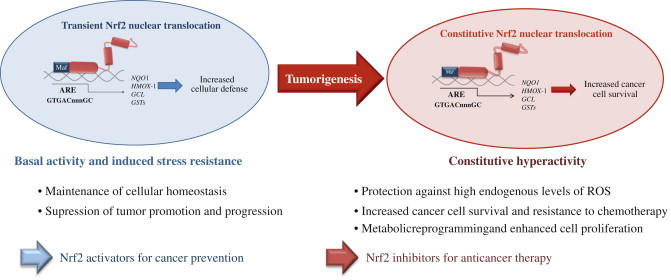

Although cytoprotection provided by Nrf2 activation is important for cancer chemoprevention in normal and premalignant tissues, in fully malignant cells Nrf2 activity provides growth advantage by increasing cancer chemoresistance and enhancing tumor cell growth [4]. Several mechanisms by which Nrf2 signaling pathway is constitutively activated in various cancers have been described: (1) somatic mutations in Keap1 or the Keap1 binding domain of Nrf2 disrupting their interaction; (2) epigenetic silencing of Keap1 expression leading to defective repression of Nrf2; (3) accumulation of disruptor proteins such as p62 leading to dissociation of the Keap1-Nrf2 complex; (4) transcriptional induction of Nrf2 by oncogenic K-Ras, B-Raf and c-Myc; and (5) post-translational modification of Keap1 cysteines by succinylation that occurs in familial papillary renal carcinoma due to the loss of fumarate hydratase enzyme activity [3–10] (Fig. 3). Constitutively abundant Nrf2 protein causes increased expression of genes involved in drug metabolism thereby increasing the resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs and radiotherapy. In addition, high Nrf2 protein level is associated with poor prognosis in cancer [4]. Overactive Nrf2 also affects cell proliferation by directing glucose and glutamine towards anabolic pathways augmenting purine synthesis and influencing the pentose phosphate pathway to promote cell proliferation [11] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The dual role of Nrf2 in tumorigenesis. Under physiological conditions, low levels of nuclear Nrf2 are sufficient for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Nrf2 inhibits tumor initiation and cancer metastasis by eliminating carcinogens, ROS and other DNA-damaging agents. During tumorigenesis, accumulating DNA damage leads to constitutive hyperactivity of Nrf2 which helps the autonomous malignant cells to endure high levels of endogenous ROS and to avoid apoptosis. Persistently elevated nuclear Nrf2 levels activate metabolic genes in addition to the cytoprotective genes contributing to metabolic reprogramming and enhanced cell proliferation. Cancers with high Nrf2 levels are associated with poor prognosis because of radio and chemoresistance and aggressive cancer cell proliferation. Thus, Nrf2 pathway activity is protective in the early stages of tumorigenesis, but detrimental in the later stages. Therefore, for the prevention of cancer, enhancing Nrf2 activity remains an important approach whereas for the treatment of cancer, Nrf2 inhibition is desirable [4,11].

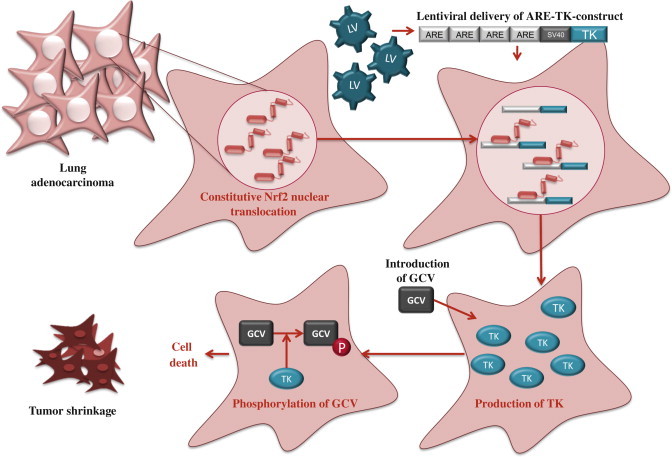

Given that high Nrf2 activity commonly occurs in cancer cells with adverse outcomes, there is a need for therapies to inhibit Nrf2. Unfortunately, due to structural similarity with some other bZip family members, the development of specific Nrf2 inhibitors is a challenging task and only a few studies of Nrf2 inhibition have been published to date. By screening natural products, Ren et al. [12] identified an antineoplastic compound brusatol as an Nrf2 inhibitor that enhances the chemotherapeutic efficacy of cisplatin. In addition, PI3K inhibitors [11,13] and Nrf2 siRNA [14] have been used to inhibit Nrf2 in cancer cells. Recently, we have utilized an alternative approach, known as cancer suicide gene therapy, to target cancer cells with high Nrf2 levels. Nrf2-driven lentiviral vectors [15] containing thymidine kinase (TK) are transferred into cancer cells with high ARE activity and the cells are treated with a pro-drug, ganciclovir (GCV). GCV is metabolized to GCV-monophosphate, which is further phosphorylated by cellular kinases into a toxic triphosphate form [16] (Fig. 5). This leads to effective killing of not only TK containing tumor cells, but also the neighboring cells due to the bystander effect [17]. ARE-regulated TK/GCV gene therapy can be further enhanced via combining a cancer chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin to the treatment [16], supporting the notion that this approach could be useful in conjuction with traditional therapies.

Fig. 5.

Suicide gene therapy. Constitutive Nrf2 nuclear accumulation in cancer cells can be exploited by using Nrf2-driven viral vector for cancer suicide gene therapy [16]. In this approach, lentiviral vector (LV) expressing thymidine kinase (TK) under minimal SV40 promoter with four AREs is transduced to lung adenocarcinoma cells. High nuclear Nrf2 levels lead to robust expression of TK through Nrf2 binding. Cells are then treated with a pro-drug, ganciclovir (GCV), which is phosphorylated by TK. Triphosphorylated GCV disrupts DNA synthesis and leads to effective killing of not only TK containing tumor cells, but also the neighboring cells due to the bystander effect.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation and the Finnish Cancer Organisations.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kansanen E., Jyrkkänen H.-K., Levonen A.-L. Activation of stress signaling pathways by electrophilic oxidized and nitrated lipids. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2012;52:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kansanen E., Kivelä A.M., Levonen A.-L. Regulation of Nrf2-dependent gene expression by 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;47:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taguchi K., Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 2011;16:123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sporn M.B., Liby K.T. NRF2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12:564–571. doi: 10.1038/nrc3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeNicola G.M., Karreth F.A., Humpton T.J., Gopinathan A., Wei C., Frese K., Mangal D., Yu K.H., Yeo C.J., Calhoun E.S., Scrimieri F., Winter J.M., Hruban R.H., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Kern S.E., Blair I.A., Tuveson D.A. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanada N., Takahata T., Zhou Q., Ye X., Sun R., Itoh J., Ishiguro A., Kijima H., Mimura J., Itoh K., Fukuda S., Saijo Y. Methylation of the KEAP1 gene promoter region in human colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P., Singh A., Yegnasubramanian S., Esopi D., Kombairaju P., Bodas M., Wu H., Bova S.G., Biswal S. Loss of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 function in prostate cancer cells causes chemoresistance and radioresistance and promotes tumor growth. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:336–346. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam J., Hatipoglu E., O'Flaherty L., Ternette N., Sahgal N., Lockstone H., Baban D., Nye E., Stamp G.W., Wolhuter K., Stevens M., Fischer R., Carmeliet P., Maxwell P.H., Pugh C.W., Frizzell N., Soga T., Kessler B.M., El-Bahrawy M., Ratcliffe P.J. Renal cyst formation in Fh1-deficient mice is independent of the Hif/Phd pathway: roles for fumarate in KEAP1 succination and Nrf2 signaling. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ooi A., Wong J.-C., Petillo D., Roossien D., Perrier-Trudova V., Whitten D., Min B.W.H., Tan M.-H., Zhang Z., Yang X.J., Zhou M., Gardie B., Molinié V., Richard S., Tan P.H., Teh B.T., Furge K.A. An antioxidant response phenotype shared between hereditary and sporadic type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:511–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Q., He X. Molecular basis of electrophilic and oxidative defense: promises and perils of nrf2. Pharmacological Reviews. 2012;64:1055–1081. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuishi Y., Taguchi K., Kawatani Y., Shibata T., Nukiwa T., Aburatani H., Yamamoto M., Motohashi H. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren D., Villeneuve N.F., Jiang T., Wu T., Lau A., Toppin H.A., Zhang D.D. Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2011;108:1433–1438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhry S., Zhang Y., McMahon M., Sutherland C., Cuadrado A., Hayes J.D. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct β-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A., Boldin-Adamsky S., Thimmulappa R.K., Rath S.K., Ashush H., Coulter J., Blackford A., Goodman S.N., Bunz F., Watson W.H., Gabrielson E., Feinstein E., Biswal S. RNAi-mediated silencing of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer inhibits tumor growth and increases efficacy of chemotherapy. Cancer Research. 2008;68:7975–7984. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurttila H., Koponen J.K., Kansanen E., Jyrkkänen H.-K., Kivelä A., Kylätie R., Ylä-Herttuala S., Levonen A.-L. Oxidative stress-inducible lentiviral vectors for gene therapy. Gene Therapy. 2008;15:1271–1279. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leinonen H.M., Ruotsalainen A.-K., Määttä A.-M., Laitinen H.M., Kuosmanen S.M., Kansanen E., Pikkarainen J.T., Lappalainen J.P., Samaranayake H., Lesch H.P., Kaikkonen M.U., Ylä-Herttuala S., Levonen A.-L. Oxidative stress-regulated lentiviral TK/GCV gene therapy for lung cancer treatment. Cancer Research. 2012;23:6227–6235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moolten F.L. Tumor chemosensitivity conferred by inserted herpes thymidine kinase genes: paradigm for a prospective cancer control strategy. Cancer Research. 1986;46:5276–5281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]