Abstract

The pro-inflammatory cytokine Interleukin-1α (IL-1α) has recently emerged as a susceptibility marker for a wide array of inflammatory diseases associated with oxidative stress including Alzheimer's, arthritis, atherosclerosis, diabetes and cancer. In the present study, we establish that expression and nuclear localization of IL-1α are redox-dependent. Shifts in steady-state H2O2 concentrations (SS-[H2O2]) resulting from enforced expression of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) drive IL-1α mRNA and protein expression. The redox-dependent expression of IL-1α is accompanied by its increased nuclear localization. Both IL-1α expression and its nuclear residency are abrogated by catalase co-expression. Sub-lethal doses of H2O2 also cause IL-1α nuclear localization. Mutagenesis revealed IL-1α nuclear localization does not involve oxidation of cysteines within its N terminal domain. Inhibition of the processing enzyme calpain prevents IL-1α nuclear localization even in the presence of H2O2. H2O2 treatment caused extracellular Ca2+ influx suggesting oxidants may influence calpain activity indirectly through extracellular Ca2+ mobilization. Functionally, as a result of its nuclear activity, IL-1α overexpression promotes NF-kB activity, but also interacts with the histone acetyl transferase (HAT) p300. Together, these findings demonstrate a mechanism by which oxidants impact inflammation through IL-1α and suggest that antioxidant-based therapies may prove useful in limiting inflammatory disease progression.

Keywords: Superoxide dismutase, Interleukin-1α, Hydrogen peroxide, Catalase, Inflammation, Nuclear localization

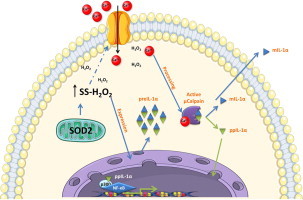

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Sod2-dependent increases in steady-state H2O2 promote IL-1α expression.

-

•

H2O2 causes nuclear localization of IL-1α and extracellular Ca2+ influx.

-

•

Inhibition of the Ca2+ regulated calpain prevents H2O2 dependent IL-1α nuclear localization.

-

•

Nuclear IL-1α interacts with p300 and promotes NF-κB activity.

Introduction

Interleukin-1α (IL-1α) is an inflammatory cytokine initially synthesized as a precursor protein that is subsequently cleaved into two functional fragments by the Ca2+ activated protease calpain [1]. Similar to the processed form of IL-1β, the C terminus of IL-1α can bind the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) at the cell surface. IL-1R ligation initiates a robust inflammatory response converging on downstream targets including NF-κB, c-jun N terminal Kinase (JNK), and p38 MAP Kinase [2]. The N terminal propiece (ppIL-1α) of IL-1α has a canonical nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and can translocate into the nucleus where it has been shown to act as a nuclear oncoprotein [3] and to promote the transcription of inflammatory genes [4,5]. In recent years, aberrant IL-1α signaling has been implicated in many diseased states including type II diabetes [6], rheumatoid arthritis [7], auto-inflammatory skin diseases [8], and cellular senescence [9,10]. Common to all the above disease processes is an alteration in redox state resulting from shifts in antioxidant enzyme expression or through shifts in metabolism [11]. While reactive oxygen species (ROS) can influence transcriptional networks including NF-κB and AP-1 [12,13], it remains unknown what affect ROS may have on IL-1α expression. Thus, we sought to further define the precise contribution of ROS in regulating IL-1α expression.

IL-1α functions as an alarmin during the process of sterile inflammation. It serves as a signal from dying cells to potentiate the inflammatory response, increasing the expression of other secreted factors like IL-6 and IL-8 [9]. Despite its important role in the process of sterile inflammation, events that affect IL-1α function are largely unknown. Recent work has established that IL-1α bioactivity can be enhanced by proteolytic processing [14]. Calpain, the protease responsible for the post-translational processing of IL-1α, is a Ca2+ activated thiol protease whose activity is primarily modulated by cytosolic Ca2+ availability [15]. As such, stimuli that increase intracellular Ca2+ concentrations may enhance calpain activity, facilitate IL-1α processing and impact its biological function. Interestingly, ROS levels and Ca2+ homeostasis are tightly linked [15–17] and disease states that are associated with elevated ROS may alter Ca2+ homeostasis creating an environment that enhances IL-1α activity.

Our findings indicate that IL-1α expression is induced by cellular H2O2 at the transcript and protein level. H2O2 also promoted the nuclear accumulation of IL-1α, which functionally correlated with increased inflammatory gene expression. This nuclear accumulation was both oxidant and calpain dependent, as calpain inhibition caused nuclear exclusion irrespective of cellular H2O2. Additionally, H2O2 treatment triggered Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space and increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels. Together these results suggest that oxidants influence Ca2+ homeostasis, altering calpain activity and driving IL-1α nuclear localization. Collectively, these data demonstrate how redox state influences the expression, localization and function of IL-1α further unveiling a novel role for oxidants in the expression of this disease associated inflammatory cytokine.

Results

IL-1α protein expression is regulated by cellular H2O2

Using HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells stably expressing cDNAs encoding the antioxidant enzymes manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and catalase (SOD2/CAT), or SOD2 alone, we measured steady-state H2O2 (SS-[H2O2]) utilizing a biochemical assay that couples catalase inhibition to the quantitative characterization of cellular H2O2 production [18]. In agreement with previous reports, the enforced expression of SOD2 leads to increases in SS-[H2O2] as compared to the empty vector control cells (CMV). This increase in SS-[H2O2] was reduced to levels below the empty vector control when co-expressing catalase, which is consistent with the ability of catalase to convert H2O2 to H2O and O2 (Fig. 1A). To assess whether redox state influences IL-1α expression, we used an ELISA assay to measure IL-1α protein levels in whole cell lysates from these same stable cell lines. IL-1α induction was clearly observed in cells overexpressing SOD2 and was completely reversed by co-expressing catalase, suggesting that H2O2 levels influence IL-1α protein levels (Fig. 1A). Basal IL-1α protein levels were also increased in cells cultured in 21% O2 compared to 3% O2 (Fig. 1B), consistent with the notion that increased oxygen tension positively correlates with ROS production [17,19]. TNF-α, a known IL-1α agonist, was used as a positive control (Fig. 1B), and its ability to induce IL-1α was further accentuated by 21% O2. Since IL-1α is initially synthesized as a precursor protein, it can either exist as a full length 31 kDa protein or as a processed 17 kDa fragment. In order to distinguish the precise protein isoform present under the above conditions, we monitored IL-1α by immunoblot with an antibody directed against its N terminal epitope. This antibody will detect both the unprocessed precursor as well as the N terminal propiece. As seen in the ELISA assays, cellular IL-1α levels mirrored shifts in SS-[H2O2] (Fig. 1C). Notably, processed IL-1α was most prominent in conditions of elevated SS-[H2O2] (Fig. 1C). While total IL-1α levels were also augmented in this state, these data suggest oxidants can additionally influence the processing status of IL-1α (Fig. 1C). Together, these data support a role of H2O2 in regulating the levels of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1α.

Fig. 1.

IL-1α protein expression is regulated by cellular H2O2. (A, White Bars) SS-[H2O2] in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells stably expressing empty vector (CMV), SOD2, or SOD2 and Catalase measured using aminotriazole inhibition of catalase. (A, Gray Bars) Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) from whole cell lysates of IL-1α protein from indicated stable cell lines normalized to total protein. (B) ELISA of IL-1α protein normalized to total protein from HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells cultured under 3% or 21% oxygen tensions +/− 5 h of TNFα treatment (10 ng/ml) as a positive control. (C) Western blot analysis of IL-1α protein in indicated stable cell lines. Data represents n≥3±SEM. ⁎p≤0.05, ⁎⁎p≤0.01, ⁎⁎⁎p≤0.001.

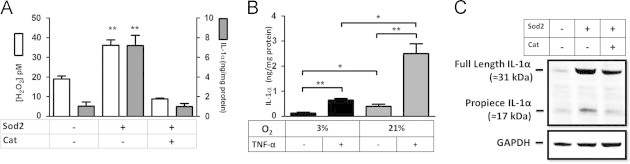

IL-1α mRNA expression is regulated by cellular H2O2

To fully understand if IL-1α's redox-dependent expression occurs at the level of transcription or post-transcription, we measured IL-1α mRNA expression in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells stably expressing SOD2 or SOD2 and catalase. Similar to IL-1α protein, IL-1α mRNA was enhanced in cells overexpressing SOD2 and was again abrogated when catalase was co-expressed (Fig. 2A). Increase in IL-1α mRNA with SOD2 overexpression was confirmed by northern blot (Fig. 2B). Moreover, basal IL-1α message increased in a dose dependent manner when increasing the cell culture oxygen tension (Fig. 2B). Our previous findings demonstrated an H2O2 dependent activation of the transcription factor AP-1 [20] and the IL-1α proximal promoter contains binding sites for this transcription factor [21]. To determine its involvement and to further characterize the redox-dependent induction of IL-1α message we conducted electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) using nuclear lysates from the stable cell lines and radiolabeled nucleic acid probes for AP-1 transcription factors. Cells overexpressing SOD2 enhanced AP-1 binding, which was abrogated by catalase co-expression or when an unlabeled consensus site competitor was used (Fig. 2C), suggesting AP-1 may participate in the redox-dependent induction of IL-1α. Collectively, these results suggest increases in SS-[H2O2] can greatly increase IL-1α transcription.

Fig. 2.

IL-1α mRNA expression is regulated by cellular H2O2. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR of IL-1α transcript from HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells with indicated stable transfectants. (B) Northern blot analysis of IL-1α message performed on total RNA extracts from cells cultured in increasing oxygen tensions (0.5%, 3%, 21%, or 50%) with and without stable SOD2, and catalase. β actin is shown for normalization. (C) Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) of nuclear lysates from indicated HT1080 stable cell lines incubated with radiolabeled probes for an AP-1 binding motif. As controls, an unlabeled competing probe (cold competitor) and a radiolabeled mutant probe were used. Data represents n≥3±SEM. ⁎p≤0.05.

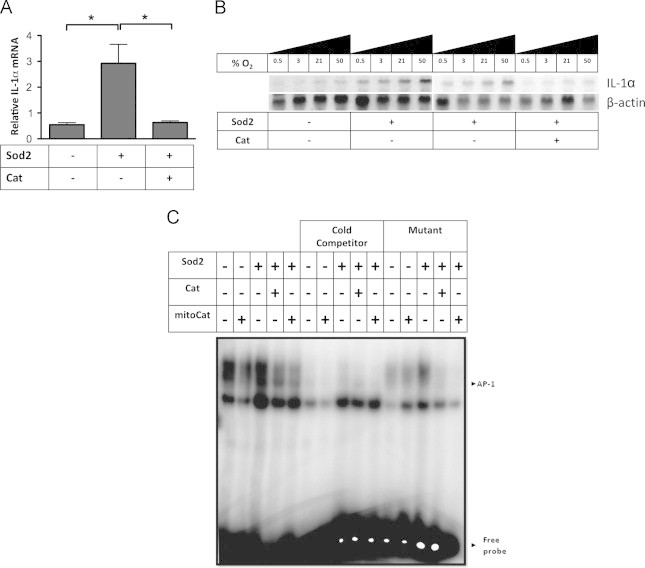

Cellular H2O2 promotes the nuclear localization of IL-1α which is independent of its cysteine residues

Since IL-1α expression is driven by increases in SS-[H2O2], we next determined the functional consequence of IL-1α in H2O2 rich environments. It is known that IL-1α can translocate into the nucleus during pathological conditions [22–24], but the reasons for this localization have remained elusive. To determine if IL-1α localization was affected by cellular oxidants, we transiently transfected a DsRED-IL-1α fusion construct into the stable antioxidant expressing HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells and monitored the sub-cellular localization of IL-1α by confocal microscopy. Interestingly, IL-1α was primarily localized to the nucleus under conditions of elevated SS-[H2O2] (Fig. 3A and B) suggesting H2O2 promotes IL-1α nuclear localization. Consistent with this, catalase co-expression prevented its nuclear localization. A DsRED empty vector control remained cytoplasmic, in all cases (Fig. 3C), demonstrating this was not a consequence of the attached fluorophore. To further characterize this translocation event, we treated cells with H2O2 and observed IL-1α localization at various times post treatment. Notably, in just 30 min, IL-1α had translocated to the nucleus (Fig. 3D) suggesting the mechanism driving this translocation event was relatively rapid. Furthermore, IL-1α nuclear residency was maintained for several hours post treatment (Fig. 3D). These observations prompted us to investigate whether IL-1α was capable of directly sensing the change in redox environment through potential oxidation of one of its two cysteine residues found in the N terminal propiece, proximal to the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) (Fig. 3E). To address this possibility, these cysteines were mutated to serines (DsRED-IL-1α C14S and DsRED-IL-1α C14S C47S) and were transiently transfected into HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells and treated with H2O2. Mutation of these residues to serine was unable to alter either basal or H2O2 treated localization and therefore these residues are not likely capable of sensing the redox environment and promoting nuclear localization (Fig. 3F). Together, these data demonstrate IL-1α localization is sensitive to alterations in redox state and suggest cysteines vicinal to the precursor peptide NLS are not contributing to its nuclear localization.

Fig. 3.

Cellular H2O2 promotes the nuclear localization of IL-1α independent of its cysteines. (A) IL-1α localization determined by confocal microscopy of redox engineered cell lines (CMV-empty vector, SOD2, SOD2 and Catalase) transiently transfected with an N terminal DsRED-IL-1α fusion construct. (B) IL-1α localization in redox engineered cell lines quantified by determining the primary localization of IL-1α in >65 cells (n=3+/−SEM). (C) Confocal microscopy of a DsRED-empty vector control transiently transfected into HT1080 cells stably expressing empty vector (CMV), SOD2, or SOD2 and catalase. (D) Confocal microscopy of HT1080 fibrosarcomas transiently transfected with a DsRED-IL-1α fusion construct, treated with H2O2 (50 µM) and fixed at indicated times post treatment. (E) Schematic representation of full length IL-1α. C indicates cysteine residues and NLS is the nuclear localization sequence. (F) Confocal microscopy of DsRED-IL-1α mutants (C14S and C14S C47S) after indicated treatments in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells. H2O2 was used at a concentration of 50 μM for 1 h prior to fixing. Data represents n≥3±SEM. ⁎p≤0.05, ⁎⁎p≤0.01.

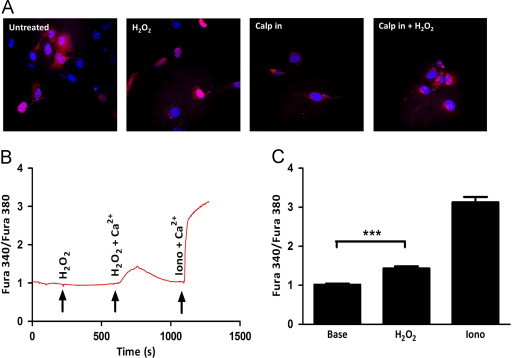

Calpain inhibition prevents IL-1α nuclear localization

Since IL-1α nuclear localization did not involve cysteine oxidation, we next asked whether calpain, the Ca2+-activated protease responsible for cleaving IL-1α, was required for its nuclear translocation. To do this, we pre-treated cells with a calpain inhibitor, MDL28170, previously demonstrated to prevent processing of IL-1α [25], followed by H2O2 treatment and monitored IL-1α localization by confocal microscopy. Strikingly, calpain inhibition caused nuclear exclusion of IL-1α even in the presence of H2O2 (Fig. 4A) demonstrating the redox-dependent nuclear localization of IL-1α was also dependent on calpain activity. Together these data suggest calpain, in response to oxidative stress, may be aberrantly active promoting the nuclear localization of its substrate IL-1α. The apparent role of calpain in affecting IL-1α localization suggests oxidants promote its activity, but to date no direct connection has been made. However, much evidence exists suggesting oxidants can influence Ca2+ homeostasis [16,26,27]. Since Ca2+ flux can activate calpain [28], we next determined if H2O2 treatment caused Ca2+ mobilization from either internal stores or the extracellular space. This was accomplished using the ratiometric Ca2+ sensitive dye, Fura2 [29,30]. To determine if H2O2 treatment caused intracellular Ca2+ release from internal organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), H2O2 was added to a Ca2+-free bath solution and intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured. As shown in Fig. 4B, H2O2 did not cause the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Fig. 4B). To assess whether extracellular Ca2+ entry occurs in response to H2O2, a bath solution replenished with Ca2+ (2 mM) and H2O2 were subsequently added to the cells and intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured. Interestingly, in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, H2O2 treatment caused an increase in intracellular Ca2+ suggesting that H2O2 stimulates Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B). This global increase was statistically significant (Fig. 4C) and comparable to global increases in Ca2+ concentrations induced by physiological agonists acting on plasma membrane receptors [31]. Localized Ca2+ gradients at the site of Ca2+ entry reach micromolar concentrations of Ca2+ that are sufficient to activate calpain protease activity [32]. The Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin was used at the end of the time course to cause maximal Ca2+ influx and demonstrate Fura2 was loaded effectively (Fig. 4B). Together, these data propose a redox-dependent alteration in Ca2+ homeostasis that may lead to aberrant calpain activity and subsequent the nuclear localization of ppIL-1α.

Fig. 4.

Calpain inhibition prevents IL-1α nuclear localization. (A) IL-1α localization determined by confocal microscopy of HT1080 fibrosarcomas with indicated treatments. The calpain inhibitor (MDL28170) was used at a concentration of 40 µM and was added to media 3 h post transfection. H2O2 was used at a concentration of 50 μM for 1 h prior to fixing. (B) Ratiometric Ca2+ imaging of HT1080 fibrosarcomas treated as indicated. H2O2 was used at a concentration of 50 μM and extracellular Ca2+ at a concentration of 2 mM. Ionomycin was used at a concentration of 10 μM and was added at the end of the time course as a control to show effective Fura2 loading. (C) Quantification of peaks in (B). Data represents n≥3±SEM. * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.001.

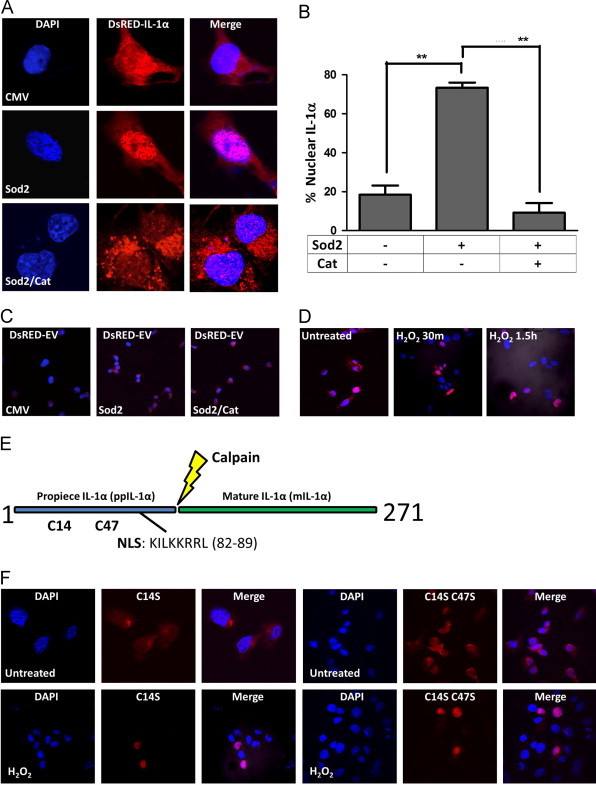

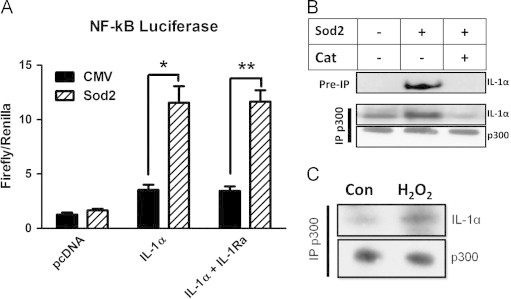

IL-1α promotes NF-κB activation and interacts with HAT p300 in a redox-dependent manner

The differential localization of IL-1α in response to oxidative stress presupposes that this shift is of functional significance. Indeed, nuclear IL-1α has been shown to promote the transcription of inflammatory genes [4] perhaps through its interaction with the histone modifying enzyme p300 [33]. To characterize the downstream consequences to shifts in cellular redox environment, we transiently expressed an IL-1α expression construct in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells stably expressing the empty vector or SOD2 and measured the activity of an NF-κB responsive promoter-luciferase construct. IL-1α expression enhanced NF-κB activity in a redox-dependent fashion promoting its activity more dramatically in cells overexpressing SOD2 (Fig. 5A). Since IL-1α can interact with the cell surface receptor IL-1R, and promote downstream signaling, we used saturating concentrations (10 ug/ml) of the recombinant receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), which outcompetes for binding at the cell surface. Interestingly, the pattern was the same in the presence of the receptor antagonist suggesting the redox-dependent increase in NF-κB activity was a consequence of the nuclear function of IL-1α. To demonstrate a possible mechanism for the increased NF-κB activity in response to IL-1α expression, we co-immunoprecipitated histone acetyl transferase (HAT) p300 and probed for its interaction with IL-1α. Endogenous IL-1α was complexed with p300 in a redox-dependent manner showing increased interaction when SOD2 was expressed (Fig. 5B). As expected, co-expression of catalase reversed the interaction with p300 consistent with the decrease in SS-[H2O2] and the nuclear exclusion of IL-1α (Fig. 5B). Since our previous assays showed IL-1α expression was influenced by SS-[H2O2] and this difference in protein abundance could compromise the interpretation of the endogenous interaction with p300, we transiently expressed IL-1α in 293 T cells and immunoprecipitated p300. Consistent with our previous assay, IL-1α's interaction with p300 was increased after treatment with H2O2, demonstrating that this interaction is redox-dependent and not an artifact of the differential expression of IL-1α in the different redox cell lines (Fig. 5C). Together, these data support the intracellular role of IL-1α as a pro-inflammatory mediator and suggests a novel regulation of this process that depends on cellular redox state. In summary, these data demonstrate the environmental redox effect on IL-1α is twofold: initially through enhanced expression and subsequently through differential localization. The consequence to this redox-regulated process may enhance the inflammatory state of the cell, further supporting a role for IL-1α in the inflammatory phenotype.

Fig. 5.

IL-1α promotes NF-κB activation and interacts with HAT p300 in a redox-dependent manner. (A) NF-κB luciferase activity of HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells expressing indicated antioxidants transiently transfected with an IL-1α expression construct. Graph represents the average of 3 independent experiments +/− SEM. Where indicated, saturating concentrations of recombinant IL-1 Receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) was used (10 ug/ml) (B) Immunoprecipitation of histone acetyl transferase p300 in indicated stable HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells followed by IL-1α immunoblot. (C) Immunoprecipitation of histone acetyl transferase p300 in 293 T cells with overexpressed IL-1α +/− 50 µM H2O2 for 1 h. Data represents n≥3±SEM. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01.

Discussion

Many diseases are the result of responses to aberrant tissue inflammation. Here, we provide evidence that the redox state of the cell is an important parameter that can shift the cellular phenotype through upregulation of the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1α. Using redox engineered fibrosarcoma cells we demonstrate IL-1α expression is largely dependent on the cellular redox environment. Specifically, we showed how steady state increases in H2O2 increased the expression of IL-1α, providing some data implicating the transcription factor AP-1. Our future efforts will further characterize the involvement of this transcription factor using more modern techniques and will work toward a detailed analysis of the local chromatin structure around the IL-1α promoter. Similarly, shifts in SS-[H2O2] have been observed in senescent cells [34], and we plan to test whether it is this characteristic of senescent cells that drives their aberrant IL-1α expression [35–37].

These findings provide further evidence to support the notion that antioxidant-based therapeutics may have real impacts on inflammatory diseases. Our data is of particular interest because IL-1α is known to amplify the inflammatory phenotype [9], and restricting its expression and subsequent biological activity with the use of antioxidant-based therapeutics would serve to prevent this cascade. Interestingly, while there is an abundance of data implicating IL-1α expression and signaling in diseases ranging from type II diabetes to aging, there are few papers that describe the mechanisms that cause the aberrant expression or function of this clinically relevant cytokine. Our findings add the necessary mechanistic insight to allow for successful therapeutic intervention.

These findings also suggest that redox state influences IL-1α localization and its processing by calpain. We ruled out the possibility that cellular oxidants directly modify IL-1α protein through mutagenesis and propose that intrinsic increases in SS-[H2O2] production controls IL-1α localization indirectly through the mobilization of extracellular, but not intracellular, Ca2+. Indeed, several lines of evidence have shown oxidants can directly impact the function of extracellular Ca2+ channels [38–41]. However, it remains to be determined in our system which plasma membrane Ca2+ channels are affected by H2O2 levels. Furthermore, since calpain requires concentrations of Ca2+ well above the global levels observed, it is of interest to determine how such local concentrations may be attained and whether or not oxidants can influence the localization and subsequent activity of calpain. These experiments are ongoing and will provide a more detailed connection between oxidative stress and Ca2+ dependent signaling events.

IL-1α processing has recently gained interest, as it was shown to increase its ability to augment the production of downstream cytokines [14]. The redox environment, through alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis, may influence this processing event and our findings indicate that shifts in SS-[H2O2] promote extracellular Ca2+ influx and IL-1α nuclear localization. It has been suggested that IL-1α may require processing for its nuclear translocation [42] via loss of a cytoplasmic retention sequence found only in the full length protein. This cleavage event releases both propiece and mature IL-1α fragments, effectively turning one molecule into two effector molecules. The latter fragment binds the IL-1R at the cell surface and is released from hematopoietic cells in a Ca2+ and calpain dependent fashion [25]. We now demonstrate that shifts in SS-[H2O2] indirectly influence this processing event by modulating Ca2+ influx. The downstream effect of enhanced IL-1α processing in redox-stressed cells may promote inflammation by two unique mechanisms: the cell surface bound mIL-1α acts through its receptor promoting an inflammatory phenotype while the N terminal propiece enters the nucleus to promote the same phenotype through an independent transcriptional pathway. Using mutagenesis, we have recently created an IL-1α construct that cannot go to the nucleus under any conditions and will use this to test the respective roles of intracellular and extracellular IL-1α. By uncoupling these functions we will determine the exact affect each fragment has in redox-stressed cells and work toward understanding how this may make them potent inflammatory inducers. It is interesting to speculate on the precise role of SOD2 in the physiological regulation of IL-1α. While we have used a system that enforces the expression of SOD2 to shift the SS-[H2O2], it has long been known that SOD2 is potently induced by a wide array of inflammatory stimuli [43]. Thus, it is possible that SOD2 induction may potentiate the inflammatory phenotype by its ability shift the redox-state of the cell, creating an environment that drives the expression and processing of the alarmin, IL-1α.

Methods

Cell culture and transfections

293T cells (ATCC CRL-11268; Washington DC) were cultured in DMEM (Corning CellGro; Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA), 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA), and 5% L glutamine (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA). HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells (ATCC CCL-121; Washington DC) stably expressing empty vector (CMV), SOD2, and SOD2/CAT were cultured in MEM (Corning CellGro; Manassas, VA) with 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA), 1000U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA), and 0.1% G418 (RPI Corp.; Mount Prospect, IL) (CMV and SOD2) and 0.5% zeocin (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) (SOD2/CAT) for selection. Cells were transfected with FugeneHD (Roche; Branford, CT) at a 2.5:1 ratio of reagent to plasmid DNA.

Measurement of cellular H2O2 via aminotriazole inhibition of catalase

The concentration of intracellular H2O2 can be determined based on the rate of irreversible inactivation of catalase by amino 1, 2, 4-triazole, which forms a covalent complex with the catalase intermediate compound I. Amino 1, 2, 4-triazole inhibition of catalase was performed as previously described [17,18,44]. Briefly, cells were treated with 20 mM amino 1, 2, 4-triazole in 15 min increments up to 1 h. Catalase activity levels were normalized to total protein of samples. Assuming non-rate limiting concentration of amino 1, 2, 4-triazole, the steady-state concentration of H2O2 was estimated from the rate of catalase inactivation. The apparent pseudo first- order rate constant for catalase inhibition by amino 1, 2, 4-triazole was obtained by plotting the natural log of catalase activity normalized to its activity at the start of the reaction. Based on [H2O2]=k/k1, where k is the first-order rate constant determined empirically for catalase inactivation in the cell, and k1 is the rate of compound I formation (1.7×10 7 M/s), we were able to derive steady state H2O2 concentrations from our different cell populations.

ELISA

ELISAs were performed using kits and procedures from R & D systems (IL-1α#DLA50; Minneapolis, MN) and were normalized to total protein.

Real time PCR

RNA was isolated from samples using Trizol (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) with random hexamers. Real Time PCR was preformed with an Applied Biosystems (AB) 7500 Real Time Thermocycler with AB SYBR Green. Specific IL-1α primers were used (Sense: 5′-AACCAGTGCTGCTGAAGG-3′; Antisense: 5′-TTCTTAGTGCCGTGAGTTTCC-3′) and the PCR conditions were as follows: 95C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of melting at 95C for 15 s, annealing and elongation at 60C for 1 min. Product specificity was verified with a melt curve.

Immunofluorescence

Cells expressing a DsRED IL-1α N terminal fusion construct were seeded on glass coverslips a day prior to imaging. The next day these cells were washed three times with 1X PBS and fixed in an appropriate volume of 3 parts acetone to 2 parts PBS. Cells were imaged using an Olympus confocal microscope FV1000. Nuclei were stained with DAPI that was present in the mounting media (Prolong Gold; Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Mutagenesis of plasmid DNA was carried out using Stratagene's QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.; Santa Clara, CA).

Primers for site directed mutagenesis

IL-1α C14S sense: GAAGACCTGAAGAACTCTTACAGTGAAAATGAAG

IL-1αC14Santisense: CTTCATTTTCACTGTAAGAGTTCTTCAGGTCTTC

IL-1αC14SC47Ssense: CCACTCCATGAAGGCAGCATGGATCAATCTGTG

IL-1αC14SC47Santisense: CACAGATTGATCCATGCTGCCTTCATGGAGTGG

Calcium imaging

Intracellular calcium levels were determined using ratiometric analysis of the excitation levels of the calcium binding dye Fura-2-AM (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) which excites at 340 nm when bound to calcium and 380 nm when unbound. Cells were seeded on 30 mm coverslips 1 day prior to imaging. Fura-2-AM (1 μM) was loaded into cells in 1X HBSS with 2 mM Ca2+ for 45 min. Fluorescent imaging of several cells was accomplished using a digital fluorescence imaging system (InCyt Im2; Intracellular Imaging, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The 340/380 nm ratio images were obtained on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Data shown is a representative trace of several experiments conducted as indicated in the figure legends.

Luciferase assays

Firefly and Renilla luciferase were measured using the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega; Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 100 ng of 3X NF-kB luciferase construct was transfected with 10 ng of the EF-1 Renilla construct in the presence or absence of 1ug of the pcDNA3.1 IL-1α construct.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Cells were washed in PBS, and then lysed in an appropriate volume of RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 1% triton-X 100, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). Either whole cell or nuclear lysates were assayed for total protein levels using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotech; Rockford, IL). Lysates for IPs were normalized to total protein and then pre-cleared with protein A agarose followed by incubation overnight at 4C with specific antibody or an isotype control. This lysate was then incubated with protein A agarose for >4 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer and subjected to western blot analysis of bound material. Protein in lysates were resolved in a NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using iBlot 7 min dry transfer system v3.0.0 (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Membranes were blocked in 5% (wt/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 30 min at room temperature followed by overnight incubation with primary antibody at 4 °C. Membranes were washed 3X in TBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Protein levels were determined by adding HRP SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Signal substrate (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, IL) followed by chemiluminescence detection.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Guangming Zhong generously provided the DsRED-IL-1α construct and Dr. Jonathan Harton generously provided the 3X NF-κB luciferase construct. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AG031067 from the National Institute of Aging.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto K., Saido T., Kawasaki H., Oppenheim J.J., Matsushima K. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:5548–5552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber A., Wasiliew P., Kracht M. Science Signaling. 2010:3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevenson F.T., Turck J., Locksley R.M., Lovett D.H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:508–513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werman A., Werman-Venkert R., White R., Lee J.K., Werman B., Krelin Y., Voronov E., Dinarello C.A., Apte R.N. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:2434–2439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308705101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S., Millis A.J., Baglioni C. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:4683–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee M., Saxena M. Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 2012;413:1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabay C., Lamacchia C., Palmer G. Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 2010;6:232–241. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldmeyer L., Werner S., French L.E., Beer H.D. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;89:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orjalo A.V., Bhaumik D., Gengler B.K., Scott G.K., Campisi J. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:17031–17036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905299106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laberge R.M., Zhou L., Sarantos M.R., Rodier F., Freund A., de Keizer P.L., Liu S., Demaria M., Cong Y.S., Kapahi P., Desprez P.Y., Hughes R.E., Campisi J. Aging Cell. 2012;11:569–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tschopp J. European Journal of Immunology. 2011;41:1196–1202. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sen C.K., Packer L. The FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1996;10:709–720. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu T.C., Young M.R., Cmarik J., Colburn N.H. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2000;28:1338–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afonina I.S., Tynan G.A., Logue S.E., Cullen S.P., Bots M., Luthi A.U., Reeves E.P., McElvaney N.G., Medema J.P., Lavelle E.C., Martin S.J. Molecular Cell. 2011;44:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontremoli S., Melloni E., Salamino F., Sparatore B., Michetti M., Horecker B.L. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:53–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galan C., Jardin I., Dionisio N., Salido G., Rosado J.A. Molecules. 2010;15:7167–7187. doi: 10.3390/molecules15107167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yusa T., Beckman J.S., Crapo J.D., Freeman B.A. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1987;63:353–358. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta J., Subbaram S., Connor K.M., Rodriguez A.M., Tirosh O., Beckman J.S., Jourd'Heuil D., Melendez J.A. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8:1295–1305. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman D.L., Salter J.D., Brookes P.S. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;292:H101–108. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00699.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasgupta J., Kar S., Liu R., Joseph J., Kalyanaraman B., Remington S.J., Chen C., Melendez J.A. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010;225:52–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moerman-Herzog A.M., Barger S.W. Life sciences. 2012;90:975–979. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawaguchi Y., Nishimagi E., Tochimoto A., Kawamoto M., Katsumata Y., Soejima M., Kanno T., Kamatani N., Hara M. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:14501–14506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng W., Shivshankar P., Zhong Y., Chen D., Li Z., Zhong G. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76:942–951. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen I., Rider P., Carmi Y., Braiman A., Dotan S., White M.R., Voronov E., Martin M.U., Dinarello C.A., Apte R.N. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:2574–2579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915018107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewamitta S.R., Nomura T., Kawamura I., Hara H., Tsuchiya K., Kurenuma T., Shen Y., Daim S., Yamamoto T., Qu H., Sakai S., Xu Y., Mitsuyama M. Infection and Immunity. 2010;78:1884–1894. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01143-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gleichmann M., Mattson M.P. Antioxidants & Redox signaling. 2011;14:1261–1273. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trebak M., Ginnan R., Singer H.A., Jourd'heuil D. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2010;12:657–674. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araujo I.M., Carreira B.P., Pereira T., Santos P.F., Soulet D., Inacio A., Bahr B.A., Carvalho A.P., Ambrosio A.F., Carvalho C.M. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14:1635–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R.Y. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsien R.Y., Rink T.J., Poenie M. Cell Calcium. 1985;6:145–157. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(85)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motiani R.K., Abdullaev I.F., Trebak M. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:19173–19183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goll D.E., Thompson V.F., Li H., Wei W., Cong J. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buryskova M., Pospisek M., Grothey A., Simmet T., Burysek L. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:4017–4026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dasgupta J., Kar S., Liu R., Joseph J., Kalyanaraman B., Remington S.J., Chen C., Melendez J.A. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010;225:52–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier J.A., Voulalas P., Roeder D., Maciag T. Science. 1990;249:1570–1574. doi: 10.1126/science.2218499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S., Vinci J.M., Millis A.J., Baglioni C. Experimental Gerontology. 1993;28:505–513. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(93)90039-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mariotti M., Castiglioni S., Bernardini D., Maier J.A. Immunity & Ageing: I & A. 2006;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayama K., Suzuki Y., Inoue T., Ochiai T., Terui T., Ra C. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2011;50:1417–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S., Ha I.S., Kim J.H., Park K.S., Han K.H., Kim S.H., Chae Y.C., Kim S.H., Kim Y.H., Suh P.G., Ryu S.H., Kim J.E., Bang K., Hwang J.I., Yang J., Park K.W., Chung J., Ahn C. Transplantation. 2008;86:1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318188ab04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giambelluca M.S., Gende O.A. Molecular and cellular Biochemistry. 2008;309:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9653-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niwa K., Inanami O., Ohta T., Ito S., Karino T., Kuwabara M. Free Radical Research. 2001;35:519–527. doi: 10.1080/10715760100301531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudo M., Kobayashi Y., Watanabe N. Zoological Science. 2005;22:891–896. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong G.H.W., Goeddel D.V. Science. 1988;242:941–944. doi: 10.1126/science.3263703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]