Abstract

Parental imprinting is an epigenetic phenomenon by which genes are expressed in a monoallelic fashion, according to their parent of origin. DNA methylation is considered the hallmark mechanism regulating parental imprinting. To identify imprinted differentially methylated regions (DMRs), we compared the DNA methylation status between multiple normal and parthenogenetic human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) by performing reduced representation bisulfite sequencing. Our analysis identified over 20 previously unknown imprinted DMRs in addition to the known DMRs. These include DMRs in loci associated with human disorders, and a class of intergenic DMRs that do not seem to be related to gene expression. Furthermore, the study showed some DMRs to be unstable, liable to differentiation or reprogramming. A comprehensive comparison between mouse and human DMRs identified almost half of the imprinted DMRs to be species specific. Taken together, our data map novel DMRs in the human genome, their evolutionary conservation, and relation to gene expression.

Highlights

-

•

Imprinted DMRs were identified by comparing normal and parthenogenetic human PSCs

-

•

The study showed some DMRs to be unstable, liable to differentiation or reprogramming

-

•

Over 20 imprinted DMRs, including a class of intergenic DMRs, were found

-

•

Comparison between mouse and human DMRs identified about half to be species specific

Introduction

Parental imprinting is a form of epigenetic regulation by which genes are expressed from only one of the two parental alleles. In humans, loss of imprinting is associated with several diseases (e.g., Prader-Willi/Angelman syndromes) and malignancies (e.g., Wilm’s tumor) (Yamazawa et al., 2010). The generation of mouse embryos containing only maternal (parthenogenetic) or paternal (androgenetic) alleles (McGrath and Solter, 1984; Surani and Barton, 1983; Surani et al., 1984) demonstrated the importance of imprinting for restricting asexual form of reproduction in placental mammals. Parthenogenesis may occur naturally in humans resulting in parthenogenetic ovarian teratomas. We have recently generated human-parthenogenetic-induced pluripotent stem cells (PgHiPSCs) by reprogramming of parthenogenetic ovarian teratomas (Stelzer et al., 2011). Studying the gene expression of PgHiPSCs enabled us to identify novel paternally expressed genes (PEGs), and to study the developmental potential of these cells (Stelzer et al., 2011). Differential marking of DNA methylation in the gametes is considered the hallmark mechanism controlling parental imprinting as it establishes germline DMRs (gDMRs), which are then maintained throughout the life of the embryo (Proudhon et al., 2012; Reik et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2012). In the past few years, global surveys of imprinted DMRs in the mouse were reported (Hiura et al., 2010; Kelsey et al., 1999; Proudhon et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2011), and recently DNA methylation analysis at single-base resolution, performed on reciprocal crosses of inbred-mice, identified dozens of novel DMRs (Xie et al., 2012). In humans, however, due to ethical and technical limitations, only few low-resolution surveys were achieved thus far (Choufani et al., 2011). Moreover, the vast majority of DMRs in humans were identified by association with certain diseases or by sharing synteny with mouse DMRs. In this study, we aimed to perform a comprehensive analysis of imprinted DMRs in humans. We thus analyzed global DNA methylation of our PgHiPSCs and their parental fibroblasts by reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) (Gu et al., 2011; Meissner et al., 2008) and compared the methylation signature to that of a large panel of human embryonic stem cells (HESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (HiPSCs) (Bock et al., 2011).

Results

Analysis of Known Imprinted DMRs in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

Parthenogenetic cells lack the paternal allele and are therefore expected to exhibit differential methylation patterns in imprinted DMRs when compared to normal biparental cells. Notably, comparing the DNA methylation signature can equally identify maternal DMRs (mDMRs), which are expected to show hypermethylation and paternal DMRs (pDMRs), which will exhibit hypomethylation when compared to normal cells (Figure S1A available online). Recently, a similar approach was used to identify epigenetic variation of known imprinted DMRs (Nazor et al., 2012). To carry out a comprehensive study of DNA methylation in PgHiPSCs, we performed RRBS on four iPSC lines derived from two independent parthenogenetic teratoma cell lines, which were shown to exhibit a complete homozygote diploid genome (Stelzer et al., 2011). Similar analysis was performed on the parental parthenogenetic teratoma cell lines. The data were then filtered and evaluated through bioinformatic analysis (Bock et al., 2010), yielding high-coverage reads and reproducible results (Figure S1B). We next compared the global DNA methylation profiles of PgHiPSCs, their parental cells with previously published data sets including 20 samples of HESCs, 12 samples of HiPSCs, and six samples of normal human fibroblasts (Bock et al., 2011). This large data set of undifferentiated and differentiated cells has previously enabled the identification of epigenetic changes associated with X inactivation (Mekhoubad et al., 2012) and was now utilized as a reference for a comprehensive study of epigenetic changes associated with parental imprinting in the different cell types. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering demonstrated that the undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells share a distinct epigenetic signature, which distinguishes them from mature parthenogenetic and normal somatic cells (Figure S2A). We then analyzed the status of methylation of known imprinted DMRs (Table 1). Since loss of imprinting is associated with disease and malignancies, perturbations in imprinted DMRs may affect the therapeutic potential of HESCs. We therefore studied the heterogeneity of known imprinted DMRs in HESCs (Figure 1A). While most of the DMRs examined maintain stable hemimethylation values in wild-type samples (average methylation calls [AMCs] between 0.3 and 0.7), few DMRs (PEG3, DIRAS3, and ZDBF2) show more variable values in the pluripotent stem cells. This effect does not seem to correlate with culture passaging as the variability was evident even in low-passage HESCs (Figure S2B). We next asked whether reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency affects the methylation levels of known DMRs. In agreement with our previous study on the stability of imprinted genes in HiPSCs (Pick et al., 2009), the vast majority of DMRs maintain hemimethylation values, thus demonstrating striking similarities between HiPSCs and HESCs (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Analysis of Previously Identified Human Imprinted DMRs

| Chromosome | Locus | CGI | Diff (ES-PG) | Parent of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr1 | DIRAS3 | Yes | 0.12 | M |

| chr2 | ZDBF2 | Yes | 0.22 | P |

| chr6 | PLAGL1 | No | 0.20 | M |

| chr7 | GRB10 | Yes | 0.29 | M |

| chr7 | PEG10/SGCE | No | 0.51 | M |

| chr7 | MEST | Yes | 0.27 | M |

| chr10 | INPP5F | Yes | 0.25 | M |

| chr11 | H19 | Yes | 0.21 | P |

| chr11 | H19 – ICR | Yes | 0.38 | P |

| chr11 | IGF2 DMR1 | No | 0.12 | P |

| chr11 | KCNQ1OT1 | Yes | 0.23 | M |

| chr14 | MEG3 | No | 0.35 | P |

| chr15 | AS-ICR | Yes | 0.48 | M |

| chr15 | SNURF-SNRPN | Yes | 0.47 | M |

| chr16 | NAT15,ZNF597 | Yes | 0.30 | P |

| chr19 | PEG3 | Yes | 0.14 | M |

| chr20 | BLCAP,NNAT | Yes | 0.16 | M |

| chr20 | L3MBTL | Yes | 0.23 | M |

| chr20 | GNASXL | Yes | 0.19 | M |

| chr20 | NESPAS | No | 0.57 | M |

| chr20 | GNAS1A | Yes | 0.21 | M |

| chr20 | GNAS1A - exon 1 | No | 0.13 | M |

List of previously identified imprinted DMRs. CGI, CpG island; M, maternal; P, paternal. See also Figure S3.

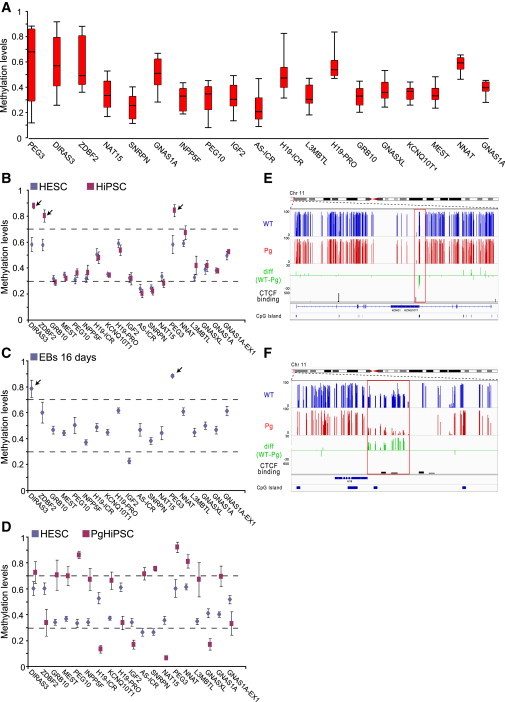

Figure 1.

Genome-wide Analysis of Imprinted DMRs in PSCs

(A) Box-plot analysis showing distribution of DNA methylation in 20 HESCs lines in known imprinted DMRs. DMRs are ordered according to the levels of heterogeneity (x axis).

(B–D) Average methylation calls ± SE of different cell types in known imprinted DMRs. DMRs are ordered by chromosome numbers (x axis); small arrows pointing to DMRs that are perturbed in the different cell types.

(E and F) Regional view of KCNQ1 and H19 known DMR. Average methylation values for wild-type PSCs (blue) and PgHiPSCs (red) of all CpG calls. Green track indicates the difference between hemimethylated (AMC between 0.3 and 0.7) wild-type PSCs and PgHiPSCs CpGs. Shown are significant putative CTCF binding sites in H1 ES cells from the ENCODE project (depicted in black rectangles, p value < 1 × 10−5) and CpG islands (UCSC) in dark-blue rectangles.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

However, the three DMRs that exhibit the highest levels of variation in HESCs show loss of imprinting in HiPSCs and are consistently hypermethylated in these cells. This can be due to loss of imprinting in the parental fibroblasts, or, alternatively, imply that these DMRs are more susceptible to aberrant methylation during reprogramming. To distinguish between the two options, we examined the methylation levels of these DMRs in the parental somatic cells (Figure S2C). Our results show that, while PEG3 and DIRAS3 DMRs exhibit loss of imprinting already in the parental cells, the ZDBF2 DMR may be prone to perturbations that are due to the reprogramming process. Studying the methylation levels of DMRs in 16-day-old embryoid bodies (EBs), that were differentiated from HESCs, further emphasized that in vitro differentiation resulted in loss of the DMR in DIRAS3 and PEG3 sites (Figure 1C). We next compared the methylation levels of known DMRs between PgHiPSCs and HESCs. Unlike normal HiPSCs, the parthenogenetic HiPSCs can be distinguished from HESCs in virtually all imprinted DMRs examined (Figure 1D), and are either hypermethylated (AMC >0.7) or hypomethylated (AMC <0.3) in comparison to the hemimethylation state of the HESCs (AMC between 0.3 and 0.7). For example, the two well-studied imprinted DMR loci KCNQ1OT and IGF2-H19 are either hypermethylated (mDMR, Figure 1E) or hypomethylated (pDMR, Figure 1F) in the PgHiPSCs, in comparison to being hemimethylated in the biparental cells.

Genome-wide Search for Novel Imprinted DMRs

In order to identify novel imprinted DMRs throughout the genome, we first verified the integrity of our data by studying the methylation values of previously discovered DMRs. Out of 22 well-established imprinted DMRs, 18 are either hypermethylated or hypomethylated in the PgHiPSCs in comparison to HESCs (methylation difference >0.15). Of the four known DMRs that could not be identified in our analysis, three also show loss of imprinting in the normal PSCs (e.g., PEG3), and one lost the imprint upon reprogramming of the parthenogenetic somatic cells into PgHiPSCs (e.g., GNAS, Figures S2D and S2E, respectively). We next searched for hemimethylation regions in both HESCs and HiPSCs and compared them to the methylation status in PgHiPSCs. In addition, we focused on regions in which the difference in DNA methylation levels between PgHiPSCs and HESCs was greater than 0.2 (see Experimental Procedures). Aberrant changes in DNA methylation, arising during the establishment of HiPSCs, are a major concern when aiming to identify epigenetic differences between normal and parthenogenetic PSCs. We therefore studied multiple HiPSC lines, derived from different sources. Furthermore, we filtered out regions of recurrent aberrant reprogramming, which were previously mapped in iPS cell lines derived from distinct tissues (Lister et al., 2011). This analysis identified 21 novel DMRs: eight of which are located in well-known imprinted regions (three of which are in the Prader-Willi/Angelman region), three are known to be imprinted in mice, and two appear in a cluster, a common phenomenon for imprinted genes (Ferguson-Smith, 2011) (Table 2, permutation test, p value = 0.011). These clustered DMRs are of specific interest as they reside in the Neuroblastoma breakpoint family (NBPF), suggesting that parental imprinting may be involved in the acquisition of the disease. Eight novel DMRs appear in regions not previously suggested to be imprinted. This type of novel DMR had good sequencing coverage and showed high levels of consistency between different samples of the same cell type (Table 2, permutation test, p value = 0.0059, see Experimental Procedures). To link between DNA methylation and gene expression on a genome-wide scale, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in two independent PgHiPSC lines and two normal HESC and HiPSC lines. Our experiment yielded highly reproducible results and deep coverage reads. Parthenogenetic cells lack the paternal genome and consequently PEGs are expected to show downregulation when compared to normal biparental cells. Interestingly, we could identify five differentially expressed genes between PgHiPSCs and normal PSCs within 200 kb of the novel DMRs, strengthening the notion that they are potentially novel imprinted genes (Figure S2F). Notably, of our 21 novel imprinted DMRs (Figure S3) five are in the Prader-Willi/Angelman region, two of which are located in the promoters of known PEGs (NDN and MAGEL2) and are considered secondary DMRs, resulting from the maternal gDMRs in this region, and three are novel DMRs residing in yet-uncharacterized regions of this locus (Figure S4A). As the complex phenotypes in both Prader-Willi and Angelman patients are still poorly understood (Mann and Bartolomei, 1999), it will be of great interest to analyze the status of these DMRs in patients.

Table 2.

Human Imprinted DMRs Identified in This Study

| Chromosome | Locus | CGI | Diff | Parent of Origin | Differential Gene Expression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMRs in known imprinted regions | chr11 | TH,ASCL2 | Yes | 0.45 | P | Yes |

| chr14 | DIO3 | Yes | 0.31 | P | No | |

| chr15 | WHAMMP3,NIPA1 | Yes | 0.23 | P | No | |

| chr15 | PWRN2 | Yes | 0.23 | P | No | |

| chr15 | LOC100289656 | Yes | 0.27 | P | No | |

| chr16 | FLYWCH1 | Yes | 0.23 | M | Yes | |

| chr20 | L3MBTL | No | 0.26 | M | No | |

| chr20 | GNAS | Yes | 0.27 | M | No | |

| DMRs syntenic to mouse | chr8 | TRAPPC9 | Yes | 0.30 | M | No |

| chr15 | NDN | Yes | 0.22 | M | Yes | |

| chr15 | MAGEL2 | Yes | 0.37 | M | Yes | |

| DMRs in clusters | chr1 | NBPF | Yes | 0.20 | P | No |

| chr1 | NBPF | Yes | 0.29 | P | No | |

| DMRs in unknown regions | chr1 | TMEM51 | Yes | 0.38 | M | Yes |

| chr5 | TSPAN17,UNC5A | Yes | 0.51 | P | No | |

| chr7 | TMEM176A/ B | No | 0.30 | P | Yes | |

| chr9 | RCL1 | Yes | 0.41 | P | No | |

| chr9 | ZNF322B | Yes | 0.31 | M | No | |

| chr10 | INPP5A | Yes | 0.22 | M | Yes | |

| chr13 | TSC22D1 | No | 0.31 | M | No | |

| chr17 | MIR301A | No | 0.43 | M | Yes |

List of new imprinted DMRs identified in this study. CGI, CpG island; M, maternal; P, paternal; Diff, difference in DNA methylation values between normal HESCs and PgHiPSCs. Differential gene expression was calculated according to the ratio in RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads) between normal and parthenogenetic cell. Fold change >2 is indicated.

Characterization of Imprinted DMRs Identifies a Novel Class of Intergenic DMRs

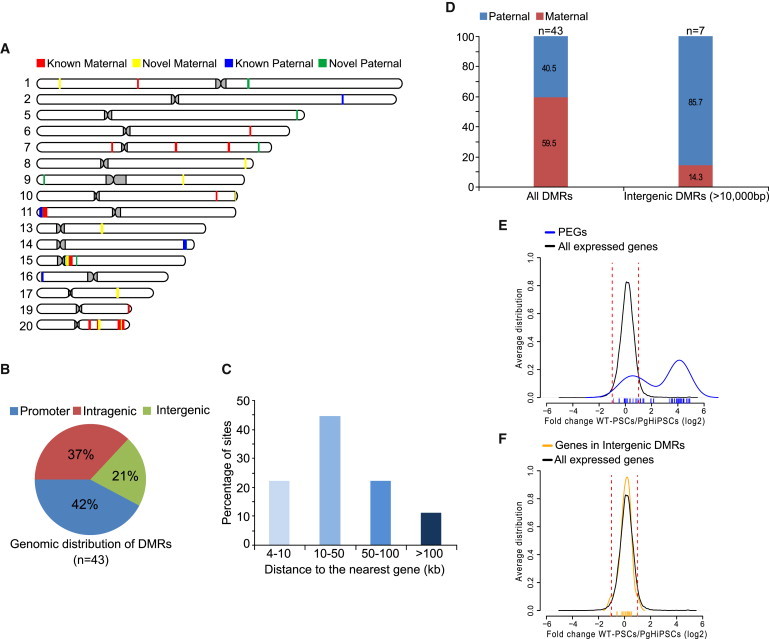

The transcription factor CTCF is a known regulator of several imprinted loci (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Bell et al., 1999; Hark et al., 2000). Intriguingly, when we analyzed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) results of CTCF binding sites in HESCs (Consortium, 2011), we could identify significant enrichments (p value < 1 × 10−5) for CTCF binding sites in proximity to many of the novel DMRs (15/21, Figures 2A and S3), but could not find this enrichment for other pluripotent transcription factors. Using locus-specific bisulfite sequencing, we confirmed two of the novel DMRs, WHAMMP3 and TAPPC9, as paternal and maternal DMRs, respectively (Figure 2B). Studying the stability of the novel imprinted DMRs in different cell types identified that all of the novel DMRs show striking similarities in methylation levels between HESCs and HiPSCs, but differ significantly from the PgHiPSCs (Figures 2C and 2D). Moreover, the vast majority of the novel DMRs are highly stable in both the undifferentiated and differentiated state (Figure 2E). A notable exception is the newly identified DMR in the L3MBTL locus, which similarly to DIRAS3 and PEG3 shows loss of imprinting following in vitro differentiation (Figure 2E). We next aimed to globally examine the properties of all imprinted DMRs identified in this study (n = 43). Plotting the chromosomal distribution of all imprinted DMRs elucidates that only a few chromosomes lack parental imprinting marks in humans (Figure 3A). The distribution of DMRs suggests that there are four genomic clusters of imprinted DMRs (IGF2-H19, DLK1-DIO3, SNURF-SNRPN, and GNAS loci), which probably result from differential gene expression (secondary DMRs) originating from the gDMRs in these loci. Two clusters (chromosomes 11 and 15) are marked by both paternal and maternal DMRs, while the two other clusters (chromosomes 14 and 20) are either complete maternal or paternal. Close examination of all imprinted DMRs (Figure 3B) shows that approximately 20% of all DMRs are not associated with genes (intragenic regions) or gene promoters and are located in intergenic region (>4 kb of any nearby gene), a significant enrichment to the previously identified group of DMRs (Figure S4B). Studying the distance between the intergenic DMRs to their nearest gene reveals that, unlike the previously identified DMRs (Figure S4C), some intergenic DMRs are located as far as 10 kb from their nearest genes (Figure 3C). Moreover, the vast majority of the intergenic DMRs that reside in gene-poor regions are of paternal origin (pDMRs, Figure 3D), which is in agreement with previous reports (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011). To link gene expression and DNA methylation at imprinted DMRs, we analyzed our RNA-seq data and compared between normal PSCs and PgHiPSCs. First, we focused on promoter and intragenic DMRs. This class of imprinted DMRs are predicted to regulate the expression of their nearby genes. However, as some imprinted DMRs were previously shown to affect genes in cluster (e.g., SNRPN intron-2 DMR), we included all genes that are within 200 kb from the DMRs. Comparing this group of genes to that of all expressed genes in PSCs shows that most genes that are associated with imprinted DMRs are downregulated in the PgHiPSCs (Figure 3E; Table S1). However, few known PEGs (e.g., INPP5F, GRB10, and MEST), and some putative imprinted genes identified in this study, are expressed at high levels in the PgHiPSCs (Table S1), while their associate imprinted DMR is hypermethylated. This suggests that some of the putative imprinted genes are tissue specific and will start to be expressed from only one of the two parental alleles at a later stage in development (Frost and Moore, 2010). It was recently shown that DNA methylation in intragenic regions may serve as alternative promoters in a tissue-specific manner (Maunakea et al., 2010); it will thus be of interest to study the monoallelic expression of these putative imprinted genes in different adult tissues. We next examined the group of novel intergenic imprinted DMRs that are located more than 10 kb from the nearest gene (Table S2). Here, we expanded our gene-expression analysis to include genes that are within 1 Mb of the DMR, in order to allow the discovery of long-range regulatory effects. Surprisingly, none of the novel intergenic DMRs had any effect on gene expression in PSCs (Figure 3F; Table S2) and thus could be classified as a novel class of intergenic imprinted DMRs. Altogether, our gene-expression analysis in the pluripotent state could document only few novel imprinted genes, suggesting that some of the novel DMRs may regulate other processes beside gene expression or are regulated in a tissue-specific manner.

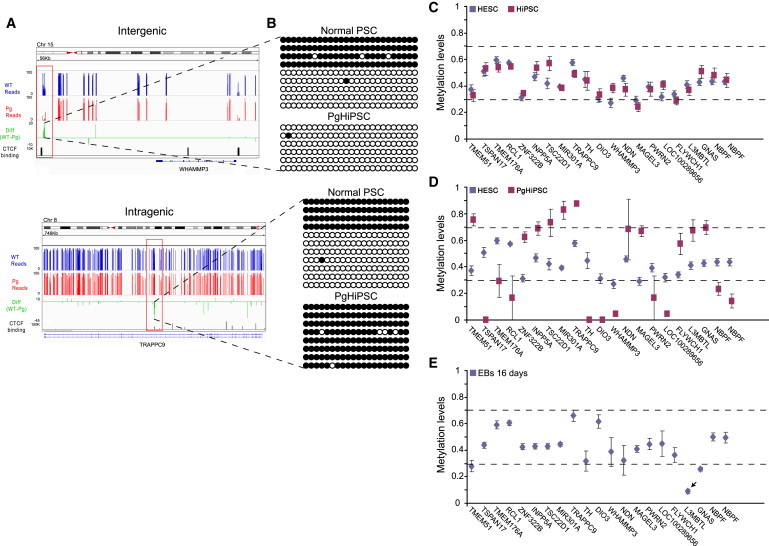

Figure 2.

Genome-wide Analysis of Imprinted DMRs in PSCs

(A) Regional view of two representative new DMR, TRAPPC9 and WHAMMP3. Average methylation values for wild-type HESCs (blue) and PgHiPSCs (red) of all CpG calls. Green track indicates the difference between hemimethylated (AMC between 0.3 and 0.7) wild-type PSCs and PgHiPSCs CpGs. Shown are significant putative CTCF binding sites in H1 ES cells from the ENCODE project (depicted in black rectangles, p value < 1 × 10−5) and CpG islands (UCSC) in dark-green rectangles. See also Figure S3.

(B) Bisulfite sequencing validation of pDMR (WHAMMP3, upper panel) and mDMR (TRAPPC9, lower panel) was conducted on normal independent PSC not included in the original analysis and PgHiPSCs lines.

(C–E) Methylation values (y axis) ± SE in various cell types across the different imprinted DMRs (x axis); small arrows pointing to DMRs that are perturbed in the different cell types. (C) Comparison between HESCs and HiPSCs demonstrate the striking similarities between the two cell types. (D) Comparison between HESCs and the PgHiPSCs showing the differences between the two cell types in methylation values, as the PgHiPSCs are either hypermethylated (AMC >0.7) or hypomethylated (AMC <0.3) in comparison to hemimethylation state (AMC between 0.3 and 0.7) of the biparental cells. (E) Analysis of methylation in 16-day-old EBs differentiated from HESCs, demonstrating that the newly identified imprinted DMRs are highly stable following in vitro differentiation. Notable exception is the DMR in the L3MBTL locus, which is consistently hypomethylated in the differentiated cells.

Figure 3.

Characterization of Imprinted DMRs Identified in This Study

(A) Chromosomal distribution of the 43 imprinted DMRs.

(B) Pie chart representing the different genomic properties of all imprinted DMRs.

(C) Distribution of distances of the imprinted intergenic DMRs to their nearest gene.

(D) Percentage of maternal and paternal DMRs; all DMRs identified (left bar) and the subset of intergenic DMRs (right panel).

(E and F) Distribution of expression ratios between normal PSCs and PgHiPSCs; x axes represent the log2 fold change between normal PSCs and PgHiPSCs, and y axes represent the distribution of frequencies for each of the samples; values for individual genes are represented by small vertical lines on the x axes; Verticals segmented red lines represent 2-fold in expression ratio. (E) Blue, genes associated with intragenic mDMRs (n = 64); black, all expressed genes (>30 reads, n = 13,223). See also Table S1. (F) Orange, genes associated with intergenic DMRs (>10 kb from the nearest gene, n = 23); black, all expressed genes.

Comprehensive Comparison between Mouse and Human Imprinted DMRs

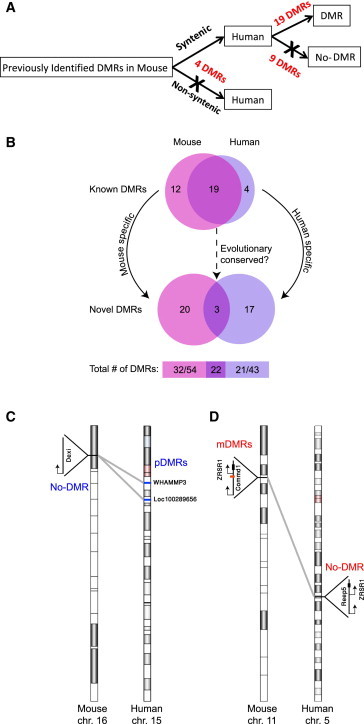

Mice serve as a good model for studying parental imprinting in humans. We therefore aimed to conduct a comprehensive comparison between mouse and human imprinted DMRs. We first examined mouse DMRs that were systematically identified in previous studies, focusing on DMRs that share synteny between mouse and human genomes and had sufficient coverage of reads in our cells. We also studied the corresponding genomic organization of mouse DMRs in which synteny was partial or not present in the human genome in order to identify putative human DMRs. Our data suggest that more than a third of the previously identified mouse imprinted DMRs do not have an equivalent DMR in the human genome (Figure 4A; Table S3). We next took advantage of a recently established single-base resolution analysis of DNA methylation in the mouse (Xie et al., 2012), to compare between mouse novel imprinted DMRs and the DMRs identified in our study. Strikingly, our analysis shows almost half of all imprinted DMRs are species specific (Figure 4B; Table S3). Genomic synteny analysis shows that some of the mouse-specific imprinted DMRs, such as Commd1/Zrsr1 DMR, lack a syntenic region in humans (Figure 4C). Since most of the studies so far were conducted in mouse, only four human-specific DMRs were identified to date. In this study, we could add 17 novel human-specific DMRs. Close examination of the data reveals that some of these DMRs may have acquired the imprint after diverging from the mouse and human common ancestor, as they share synteny with regions in which imprinted DMR was not identified in the mouse (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Synteny Analysis between Mouse and Human Imprinted DMRs

(A) DNA methylation analysis of previously identified mouse DMRs in human syntenic regions. See also Table S3.

(B) Vann diagram demonstrating species-specific imprinted DMRs in known DMRs (upper panel), and in novel DMRs (lower panel) identified either by Xie et al. (2012) (left subset) or in our study (right subset). Bottom numbers represent the number of species-specific DMRs (left and right) and shared DMRs among species. See also Table S3.

(C and D) (C) Synteny analysis of mouse-specific DMR in the Commd1/Zrsr1, and (D) the human-specific DMRs WHAMMP3 and LOC100289656 that resides in the Prader-Willi/Angelman region.

Discussion

In this study, we identified altogether 21 novel imprinted DMRs, including a novel class of intergenic DMRs, which reside in regions with no apparent imprinted genes in PSCs. This class of imprinted DMRs either may regulate genes in a tissue-specific manner, thus adding to the complexity of parental regulation in the adult tissues, or these parental marks regulate genes that are yet to be discovered. Notably, both WHAMMP3 and LOC100289656, intergenic pDMRs in the Prader-Willi/Angelman region, are located in close proximity to a cluster of piRNAs. This class of regulatory small noncoding RNAs was previously linked with parental imprinting (Watanabe et al., 2011), and thus it is attractive to suggest that this specific cluster of genes is expressed in a monoallelic fashion. The previously identified complex three-dimensional organization of the genome (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009) also suggests that this class of intergenic DMRs may interact with genes located in remote regions, thus regulating them in trans. Alternatively, it is plausible that this novel class of intergenic DMRs regulates other processes beside gene expression. As it was previously suggested, parental imprinting may be involved in marking the parental genomes for recombination (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al., 2000). It will thus be of great interest to study whether these intergenic DMRs may serve as hot spots for genetic processes such as recombination. The use of mouse model systems has greatly enhanced our understanding of parental imprinting. Yet, some genes that are imprinted in the mouse are not imprinted in the human orthologous gene (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011). Moreover, some mouse models fail to recapitulate phenotypes associated with human-imprinted syndromes (Mann and Bartolomei, 1999). Strikingly, our data imply that more than 50% of mouse- and human-imprinted DMRs are species specific. In addition, some of these DMRs (e.g., WHAMMP3 and LOC100289656) reside in loci, which are associated with known human diseases such as Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Therefore, our results emphasize the importance of studying imprinted DMRs in human. In addition, our analysis identified that several imprinted DMRs are consistently perturbed in HESCs and HiPSCs and thus should be carefully evaluated if these cells are to be used for clinical applications. Furthermore, as loss of imprinting was correlated before with different types of cancers, it will be worthy to study the differential methylation status of both previously identified and novel imprinted DMRs in tumor cell types.

The genomic coverage of RRBS is ∼10%; however, it covers the majority of CpG islands (CGIs) and promoters in the human genome (Harris et al., 2010). As the vast majority of previously identified imprinted DMRs reside in CGIs and promoters (82%, Figure S4D), our methodology is highly informative for identifying novel imprinted DMRs throughout the human genome. Future studies, using whole genome single-base resolution analysis of DNA methylation, will elucidate whether additional imprinted DMRs are also present in CpG-poor regions. In conclusion, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of imprinted DMRs in humans, identifying multiple novel DMRs, many of them not associated with gene expression. Our data shed light on the extent of the phenomenon of parental imprinting, suggesting that it may play a more extensive role than was previously thought.

Experimental Procedures

Genomic DNA Isolation

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the parthenogenetic iPS and teratoma cells using genomic DNA extraction kit (Real Biotech Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing libraries were generated as previously described in Gu et al. (2011). Raw data were analyzed using the bioinformatic pipeline described in Bock et al. (2010).

Bioinformatic Analysis

To identify novel imprinted DMRs throughout the genome, we searched for hemimethylated regions in both HESCs and HiPSCs and compared them to the methylation values of the parthenogenetic samples (difference between PgHiPSCs and HESCs was >0.2). A series of filters was implied in order to avoid false-positive hits. Specifically, only regions that exhibited low variation between all CpGs (SD < 0.2 in at least 60% of the samples for each cell type) were considered. Further filtering was performed by verifying high levels of consistency between the samples in each group (SD for average regional methylation value <0.2). Next, in order to rule out false DMRs created by aberrant reprogramming (Lister et al., 2011), all regions in which there was no agreement between PgHiPSCs and their parental fibroblasts (difference between parthenogenetic and teratoma <0.2) were filtered out. Next, a more stringent approach was used in order to confidently identify imprinted DMRs in previously unknown imprinted regions. Thus, in addition to the above-mentioned criteria only regions with more than four shared CpGs and with minimal coverage of five reads among all samples were used in this study. As imprinted DMRs are maintained throughout the development of the embryo, we also looked for hemimethylated regions in normal fibroblasts. Finally, we included only regions that met the following criteria: (1) methylation difference between PgHiPSCs and HESCs >0.2; (2) methylation difference between PgHiPSCs and HiPSCs >0.15; and (3) methylation difference between parthenogenetic teratomas and normal fibroblasts >0.15.

Statistical Analysis

In order to faithfully identify DMRs, all reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) regions with missing values were removed. In addition, as X inactivation results in large-scale differential methylation between the active and inactive X chromosomes both sex chromosomes were removed from the analysis, leaving 235,080 informative regions. Statistical significance of the identified DMRs was assessed by random permutations of samples between groups and recalculation of the average methylation and statistical values for each region. Permutated data sets were subject to the same criteria used to identify the DMRs and were generated until 20 random data sets gave at least the same number of DMRs as the original data set. p value was calculated as the probability of receiving the same number of hits in random data sets.

PCR Bisulfite Sequencing

Genomic DNA (2 μg) was bisulfite-converted using EZ DNA methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCRs were performed using Faststart Taq DNA polymerase (Roche) using primers designed to amplify suspected DMRs. Following amplification, PCR products were cleaned using Gel/PCR DNA fragments extraction kit (Geneaid) and ligated into pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega) and transformed into DH5α bacteria subjected to white/blue screen. Positive colonies were picked, and plasmid DNA was extracted for sequencing using Geneaid high-speed plasmid mini kit (New Taipei City, Taiwan). For a full list of primers, see primer list in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bisulfite Sequencing Primer List

| DMR | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Seq | TRAPPC9 | GGTTTTAGTAGTATTAGGTA | AAACTCTTTACCCTATAAAT |

| WHAMMP3 | GAGATTTTATTTTAAGTATTTA | CTAAAACCCAACCCTACTTCTATC |

High-Throughput Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using MirVana microRNA isolation kit (Ambion Inc) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA libraries were established following ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion (RiboMinus Invitrogen). The SOLiD (version 3.5) sequencing system (Life Technologies) was used to generate 35-bp-long reads. Following barcode matching of the samples, reads were aligned to UCSC complete build (GRCh37/hg19) genome. All sequences that matched RNA contaminants such as transfer RNA, rRNA, and DNA repeats were subsequently filtered. Reads for each transcript was calculated in RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads) units, to obtain normalization of the number of reads relative to their transcript length.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tamar Golan-Lev for her assistance with the graphic design. N.B. is the Herbert Cohn Chair in Cancer Research. This research was supported by The Legacy Heritage Biomedical Program of the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1252/12), and by the Centers of Excellence Legacy Heritage Biomedical Science Partnership (grants No. 1801/10). D.R. is supported by the Lady Davis Fellowship Trust and the Israel Cancer Research Fund. A.M. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator. Part of this work was funded by NIH grants (U01ES017155 and P01GM099117) and The New York Stem Cell Foundation.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Alexander Meissner, Email: alexander_meissner@harvard.edu.

Nissim Benvenisty, Email: nissimb@cc.huji.ac.il.

Accession Numbers

The GEO accession number for the RRBS data reported in this paper is GSE47088.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bartolomei M.S., Ferguson-Smith A.C. Mammalian genomic imprinting. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A.C., Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A.C., West A.G., Felsenfeld G. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell. 1999;98:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock C., Tomazou E.M., Brinkman A.B., Müller F., Simmer F., Gu H., Jäger N., Gnirke A., Stunnenberg H.G., Meissner A. Quantitative comparison of genome-wide DNA methylation mapping technologies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1106–1114. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock C., Kiskinis E., Verstappen G., Gu H., Boulting G., Smith Z.D., Ziller M., Croft G.F., Amoroso M.W., Oakley D.H. Reference Maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell. 2011;144:439–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choufani S., Shapiro J.S., Susiarjo M., Butcher D.T., Grafodatskaya D., Lou Y., Ferreira J.C., Pinto D., Scherer S.W., Shaffer L.G. A novel approach identifies new differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with imprinted genes. Genome Res. 2011;21:465–476. doi: 10.1101/gr.111922.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium E.P., ENCODE Project Consortium A user’s guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson-Smith A.C. Genomic imprinting: the emergence of an epigenetic paradigm. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrg3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost J.M., Moore G.E. The importance of imprinting in the human placenta. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Smith Z.D., Bock C., Boyle P., Gnirke A., Meissner A. Preparation of reduced representation bisulfite sequencing libraries for genome-scale DNA methylation profiling. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:468–481. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hark A.T., Schoenherr C.J., Katz D.J., Ingram R.S., Levorse J.M., Tilghman S.M. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 2000;405:486–489. doi: 10.1038/35013106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R.A., Wang T., Coarfa C., Nagarajan R.P., Hong C., Downey S.L., Johnson B.E., Fouse S.D., Delaney A., Zhao Y. Comparison of sequencing-based methods to profile DNA methylation and identification of monoallelic epigenetic modifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiura H., Sugawara A., Ogawa H., John R.M., Miyauchi N., Miyanari Y., Horiike T., Li Y., Yaegashi N., Sasaki H. A tripartite paternally methylated region within the Gpr1-Zdbf2 imprinted domain on mouse chromosome 1 identified by meDIP-on-chip. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4929–4945. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey G., Bodle D., Miller H.J., Beechey C.V., Coombes C., Peters J., Williamson C.M. Identification of imprinted loci by methylation-sensitive representational difference analysis: application to mouse distal chromosome 2. Genomics. 1999;62:129–138. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E., van Berkum N.L., Williams L., Imakaev M., Ragoczy T., Telling A., Amit I., Lajoie B.R., Sabo P.J., Dorschner M.O. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R., Pelizzola M., Kida Y.S., Hawkins R.D., Nery J.R., Hon G., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., O’Malley R., Castanon R., Klugman S. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M.R., Bartolomei M.S. Towards a molecular understanding of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:1867–1873. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunakea A.K., Nagarajan R.P., Bilenky M., Ballinger T.J., D’Souza C., Fouse S.D., Johnson B.E., Hong C., Nielsen C., Zhao Y. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature. 2010;466:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature09165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J., Solter D. Completion of mouse embryogenesis requires both the maternal and paternal genomes. Cell. 1984;37:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A., Mikkelsen T.S., Gu H., Wernig M., Hanna J., Sivachenko A., Zhang X., Bernstein B.E., Nusbaum C., Jaffe D.B. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhoubad S., Bock C., de Boer A.S., Kiskinis E., Meissner A., Eggan K. Erosion of dosage compensation impacts human iPSC disease modeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazor K.L., Altun G., Lynch C., Tran H., Harness J.V., Slavin I., Garitaonandia I., Müller F.J., Wang Y.C., Boscolo F.S. Recurrent variations in DNA methylation in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated derivatives. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:620–634. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena F., de la Casa-Esperón E., Sapienza C. Natural selection and the function of genome imprinting: beyond the silenced minority. Trends Genet. 2000;16:573–579. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick M., Stelzer Y., Bar-Nur O., Mayshar Y., Eden A., Benvenisty N. Clone- and gene-specific aberrations of parental imprinting in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2686–2690. doi: 10.1002/stem.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudhon C., Duffié R., Ajjan S., Cowley M., Iranzo J., Carbajosa G., Saadeh H., Holland M.L., Oakey R.J., Rakyan V.K. Protection against de novo methylation is instrumental in maintaining parent-of-origin methylation inherited from the gametes. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:909–920. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W., Dean W., Walter J. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science. 2001;293:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1063443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Wu X., Lee D.H., Li A.X., Rauch T.A., Pfeifer G.P., Mann J.R., Szabó P.E. Chromosome-wide analysis of parental allele-specific chromatin and DNA methylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:1757–1770. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00961-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Z.D., Chan M.M., Mikkelsen T.S., Gu H., Gnirke A., Regev A., Meissner A. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature. 2012;484:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nature10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer Y., Yanuka O., Benvenisty N. Global analysis of parental imprinting in human parthenogenetic induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:735–741. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani M.A., Barton S.C. Development of gynogenetic eggs in the mouse: implications for parthenogenetic embryos. Science. 1983;222:1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.6648518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani M.A., Barton S.C., Norris M.L. Development of reconstituted mouse eggs suggests imprinting of the genome during gametogenesis. Nature. 1984;308:548–550. doi: 10.1038/308548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Tomizawa S., Mitsuya K., Totoki Y., Yamamoto Y., Kuramochi-Miyagawa S., Iida N., Hoki Y., Murphy P.J., Toyoda A. Role for piRNAs and noncoding RNA in de novo DNA methylation of the imprinted mouse Rasgrf1 locus. Science. 2011;332:848–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1203919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Barr C.L., Kim A., Yue F., Lee A.Y., Eubanks J., Dempster E.L., Ren B. Base-resolution analyses of sequence and parent-of-origin dependent DNA methylation in the mouse genome. Cell. 2012;148:816–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazawa K., Ogata T., Ferguson-Smith A.C. Uniparental disomy and human disease: an overview. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 2010;154C:329–334. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.