Abstract

Background:

Intrathecal clonidine prolongs spinal anesthesia but the optimum dose to be used in cesarean delivery is not yet known. We evaluated the effect of addition of intrathecal clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative pain after lower segment caesarean section.

Methods:

A total of 105 parturients carrying a singleton fetus at term, scheduled to undergo elective LSCS under spinal anesthesia were randomized in a double blind fashion to one of the three groups. Group BF (n=35) received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine+25 μg fentanyl, Group BC50 (n=35) received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine+50 μg clonidine, Group BC75 (n=35) received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine+75 μg clonidine.

Results:

The duration of postoperative analgesia was 184.73±68.64 min in group BF, 360.71±86.51 min in group BC50 and 760.50±284.03 min in group BC75, P<0.001. The incidence of hypotension was comparable, P=0.932, whereas the incidence of nausea and pruritis was significantly lower in groups BC50 and BC75 as compared to group BF, P<0.001. No other side effects of intrathecal clonidine were detected. Neonatal outcome was similar in all the three groups.

Conclusions:

Addition of 75 μg clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for LSCS significantly prolongs the duration of postoperative analgesia without any increase in maternal side effects. There was no difference in neonatal outcome.

Keywords: Caesarean section, clonidine, intrathecal, postoperative pain

INTRODUCTION

Neuraxial anesthesia is now the preferred technique for lower segment caesarean sections (LSCS). Although epidural, spinal, continuous spinal, and combined spinal epidural techniques have all been advocated, most caesarean sections are performed under single-shot spinal anesthesia.[1] Even when a long acting local anesthetic like bupivacaine is used, the duration of spinal anesthesia (SA) is short and higher doses of analgesics are required in the postoperative period. Therefore, achieving a subarachnoid block that provides high quality postoperative analgesia of consistently prolonged duration is an attractive goal. Opioids such as morphine, fentanyl, and sufentanil have been administered intrathecally as adjuncts to increase the duration of postoperative analgesia. Although they ensure superior quality of analgesia, they are associated with many side effects such as pruritis, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, and especially late and unpredictable respiratory depression.[2] This has directed the research toward the use of newer and better local anesthetic additives for SA such as neostigmine, ketamine, midazolam, and clonidine.[3]

Clonidine is a α2 adrenergic agonist. As with lipophilic opioids, it is possible to achieve analgesia from systemic, epidural, or intrathecal administration of clonidine. Adding clonidine to intrathecal (IT) bupivacaine provides effective, prolonged, and dose dependent analgesia with a consequently decreased requirement for supplemental analgesics.[4] It has been used successfully as a sole analgesic for pain relief in labor[4] and also as a sole analgesic for pain relief after caesarean section.[5] As per the available literature, different dosages of clonidine, ranging from 30 to 150 μg have been used in SA for caesarean sections producing a variable duration of postoperative analgesia. No ideal dose has yet been found that can produce optimum analgesia with minimum side effects. Therefore, the present study has been planned to investigate whether the addition of two different dosages (50 and 75 μg) of IT clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine increases the duration of post-caesarean analgesia as compared to addition of fentanyl.

METHODS

Patients

After institutional ethical committee approval (Ref: PG protocol/No-5/2010-2011/LHMC) the study was conducted in the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Shrimati Sucheta Kriplani Hospital, in 105 healthy parturients (ASA physical status I and II) carrying a singleton fetus at term, scheduled to undergo elective LSCS under SA. The patients were recruited between October 2010 and March 2012. Patients who refused spinal anesthesia, had any contraindication to regional anesthesia, had fetal distress, preterm gestation, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, weighed more than 90 kg, were less than 140 cm or more than 170 cm in height, had any major co-morbidity or if they were unable to communicate in either English or Hindi language were excluded from this study.

Study procedure

After a detailed pre-anesthetic check-up and investigation, a written informed consent was taken from patients before their participation in the study. Patients were kept fasting overnight. Antacid prophylaxis with a gastric prokinetic agent (ranitidine 50 mg and metoclopramide 10 mg I/V) was given to all the patients. On arrival in the operating room, after patient orientation, standard anesthesia monitors were attached, which included pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, and non-invasive blood pressure and the baseline readings were recorded. An intravenous catheter was placed, and patients were preloaded with 12-15 ml kg-1 colloid (6% Hydroxyethyl Starch, HES®) before induction of spinal anesthesia.

Randomization and allocation of subjects to the three study groups were made by a computer generated random number assignment before the start of the study and sealed in envelopes that were opened just before entry in the study:

Group BF: 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine +25 μg fentanyl (0.5 ml) (n=35)

Group BC50: 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine +50 μg clonidine (0.33 ml, made to 0.5 ml by adding 0.17 ml normal saline) (n=35)

Group BC50: 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine+75 μg clonidine (0.5ml) (n=35)

SA was performed at L3-4 or L4-5 intervertebral space with the patient in sitting or lateral decubitus position. In a 2 ml syringe 1% lignocaine was used for skin infiltration. Under aseptic technique, a disposable 25G spinal Quincke needle was introduced and the correct position of the needle was confirmed by the free flow of CSF when the stylet was withdrawn. The syringe containing the exact volume of premixed medication to be injected was attached. A small quantity of CSF was aspirated before injection and premixed medication was injected at the rate of 1 ml per 10 s.

The total volume of drug injected was made to 2.5 ml in each group. All the drugs were prepared by an anesthesiology resident not involved in the study. The needle was then withdrawn and the patient was immediately placed in the wedged supine position.

Patient's electrocardiogram with heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial blood pressure, and peripheral oxygen saturation was monitored and recorded throughout the surgery at every 3 min till the delivery of baby and every 5 min thereafter until the end of procedure. The onset of sensory block [Hollmen scale: 0=ability to appreciate a pinprick as sharp, 1=ability to appreciate a pinprick as less sharp, 2=inability to appreciate a pin prick as sharp (analgesia), 3=inability to appreciate a pin touching (anesthesia)] was determined by pinprick method every 1 min till T6 level was achieved. Time from giving the subarachnoid block to the time when Hollmen scale 3 was achieved at T6 level was recorded as the time of onset of sensory block. Motor block was evaluated using the Bromage scale. Time from giving the subarachnoid block to the time when Bromage scale grade 4 was achieved was recorded as time of onset of motor block.

If hypotension occurred (systolic blood pressure lower than 20% of baseline value), it was treated with 5 mg boluses of intravenous ephedrine. Injection atropine 0.6 mg intravenous was administered if bradycardia (heart rate <50 beats per minute) occurred. Oxygen was administered through simple facemask at 5 L min-1 when there was hypotension and/or when arterial oxygen saturation decreased to <95℅. Umblical artery blood pH and pO2 were measured at delivery. The Apgar score of the newborn was recorded at 1 min and at 5 min after birth.

Side effects such as hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 20% of the initial value), bradycardia (heart rate <50 beats per minute), nausea, vomiting, dry mouth; pruritis and shivering were recorded. Maternal sedation was recorded using the 4 point ordinal sedation scale (1=wide awake and alert, 2=awake but drowsy, responding to verbal stimulus, 3=arousable, responding to physical stimulus, 4=not arousable, not responding to physical stimulus) every 15 min till the end of procedure. Quality of surgical anesthesia was also noted at the end of procedure on a 4 point scale (Excellent: No supplementary sedative or analgesic required, Good: Only sedative required, Fair: Both sedative and analgesic required, Poor: General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation required). Insufficient intraoperative analgesia (on patients request), if any, was treated with intravenous bolus of injection ketamine (0.5-1.0 mg kg-1) or general anesthesia and the patient was then excluded from the study. Duration of sensory block defined as the time from IT injection of drug to the time till regression of anesthesia below T12 dermatome was noted. Duration of motor blockade, defined as the time from IT injection of drug to the time till Bromage scale reaches grade 1 was also recorded.

The duration of postoperative analgesia, defined as the time from IT injection of the drug to the time when patient first requests analgesia in the postoperative period, and the verbal numerical rating scale (VNRS) at that time, was recorded. Inj diclofenac sodium 1.5 mg kg-1 intramuscularly was given as the postoperative analgesic. In the postoperative period, pain, maternal heart rate, blood pressure, and sedation were recorded every 30 min for the first 2 h and thereafter hourly till the time to first analgesic request. All the observations were made by an anesthesiology resident who was unaware of group allocation and blinded to the study drug.

Outcome

The primary outcome was the duration of postoperative analgesia. The secondary outcomes were possible clonidine side effects (dryness of mouth, sedation), perioperative hemodynamic changes (hypotension and bradycardia), onset of sensory and motor block, quality of surgical anesthesia, duration of sensory and motor blockade, amount of ephedrine required, postoperative pain scores, and side effects in the newborn.

Sample size calculation

Power analysis based on the pilot cases done prior to the study had indicated that at least 29 patients in each group will be required to demonstrate a clinically significant difference (50% increase) in the duration of postoperative analgesia with an a = 0.05 and a power of 90%. Assuming a 20% drop out rate, 35 patients were recruited in each trial arm.

Analysis

The data were compiled, tabulated, and statistically analyzed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for analysis of continuous variables and Chi-square (χ2) test for categorical variables. If the F-value was significant and variance was homogeneous, Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to assess the differences between the individual groups, otherwise Tamhane's T2 test was used. SPSS software statistical computer package version 17 was used for analysis. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD and categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentage. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

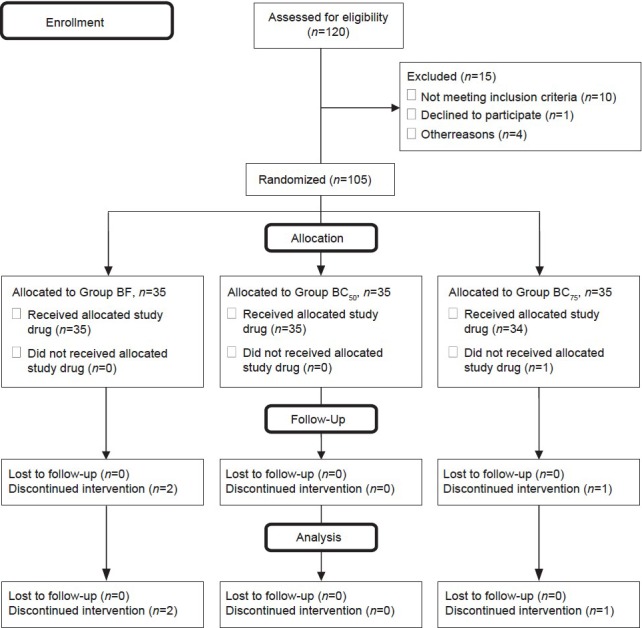

In our study, total of 105 healthy parturients were randomized. After randomization, three patients could not be analyzed leaving 102 patients for the study [Figure 1]. In one patient excessive blood loss occurred intraoperatively (group BF), in another patient there was no effect of spinal anesthesia (group BF) while the third patient was extremely restless and anxious and thus refused spinal anesthesia (group BC75). So, general anesthesia was given in these patients and they were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram

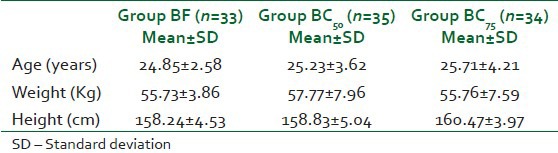

There was no difference between the three groups with respect to age, weight, and height of patients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

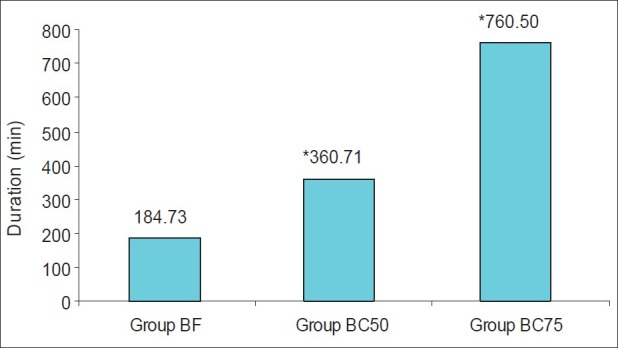

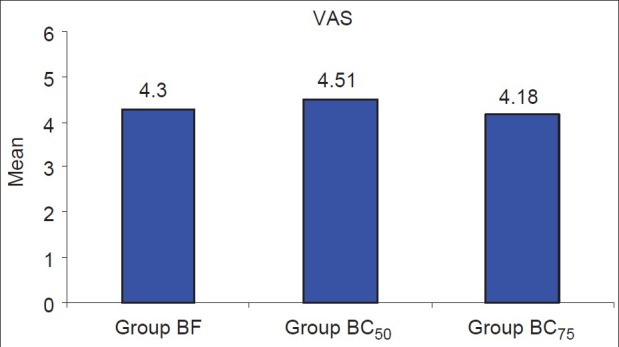

The duration of postoperative analgesia was 184.73±68.64 min in group BF, 360.71±86.51 minutes in group BC50 and 760.50±284.03 min in group BC75 [Figure 2]. This difference was clinically and statistically extremely significant between the groups BF and BC50 (P<0.001), between groups BF and BC75 (P<0.001) and between groups BC50 and BC75 (P<0.001). The VNRS at time for first analgesic request was however comparable between all the three groups (P=0.145, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Postoperative analgesia

Figure 3.

VNRS Score at time of first analgesic request

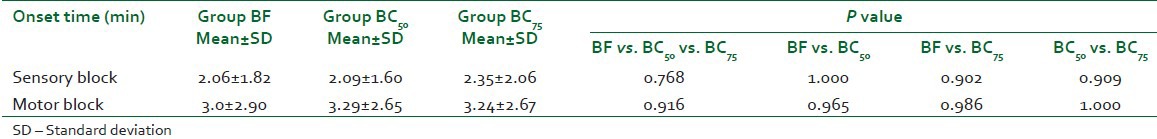

The onset time of sensory block and motor block was comparable between the three groups (P=0.768, 0.916, respectively, Table 2). The mean duration of sensory block is given in Table 3. This difference was statistically highly significant between groups BF and BC50 (P<0.001) and between groups BF and BC75 (P<0.001) but it was not significant between groups BC50 and BC75 (P=0.076). The mean duration of motor block was similar between the three groups (P=0.060, Table 3).

Table 2.

Onset time for sensory block and motor block

Table 3.

Duration of sensory block and motor block

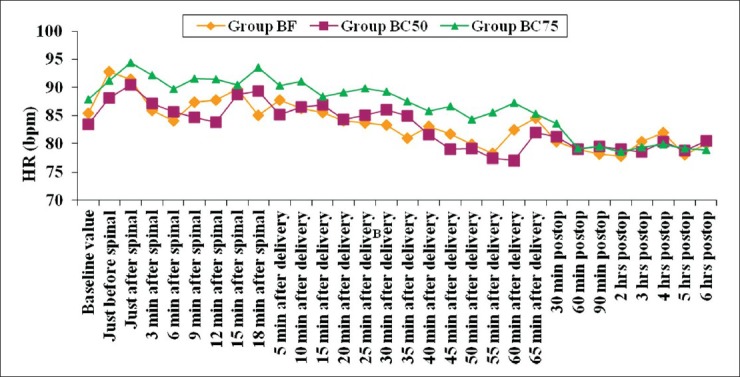

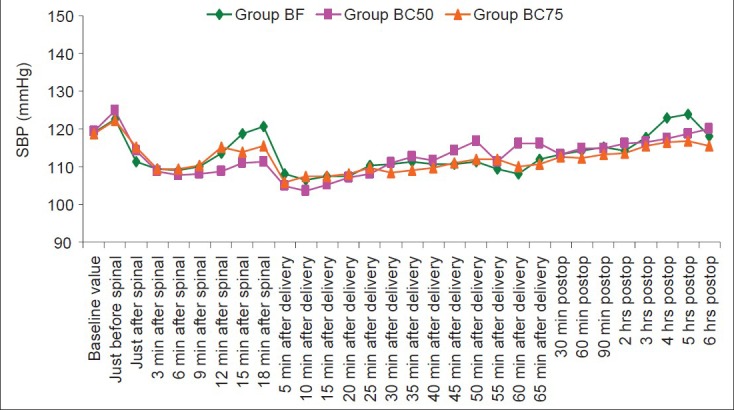

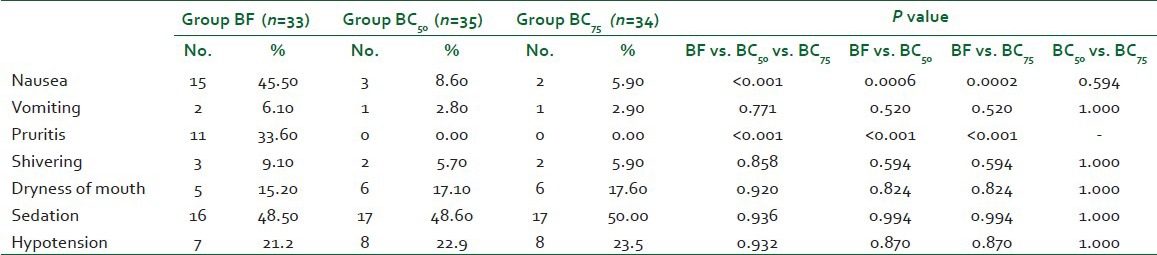

The change in mean heart rate at all time points was insignificant between the groups [Figure 4]. Two patients, one in group BF (0.03%) and one in group BC75 (0.029%) had bradycardia that was easily treated with the use of 0.6 mg of intravenous atropine. There is a decreasing trend in blood pressures in all the three groups during the intraoperative period [Figure 5]. The readings, however, do not show the actual effect of IT drugs on blood pressure as the patients who had hypotension received intravenous ephedrine for its management. Therefore, the number of patients in all the groups who had hypotensive episodes and required ephedrine were individually analyzed. The incidence of hypotension in group BF was 21.2% (7 patients), in group BC50 was 22.9% (8 patients), and in group BC75 was 23.5% (8 patients, Table 4). The difference was not clinically and statistically significant (P=0.932) among the three groups. The fall in systolic blood pressure occurred most frequently at either 3 to 6 min after spinal anesthesia or at 5 to 10 min after delivery except in one patient in group BC50 (fall occurred at 25 min after delivery) and one patient in group BC75 (fall occurred at 35 min after delivery). The total requirement of ephedrine was only slightly higher in groups BC75 and BC50 (45 mg each) as compared to group BF (35 mg).

Figure 4.

Heart rate

Figure 5.

Systolic blood pressure

Table 4.

Side effects

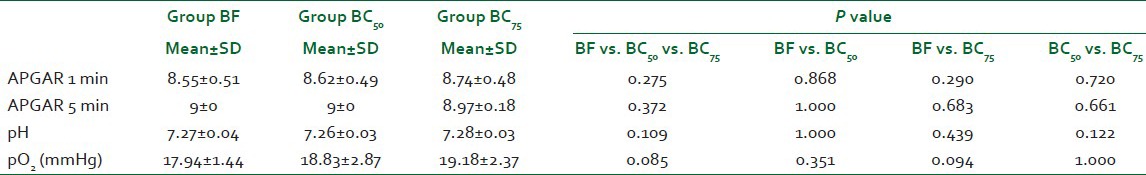

The incidence of nausea was significantly higher in group BF (45.50%) as compared to both groups BC50 (8.60%) and BC75 (5.90%, P<0.001) but it was comparable between group BC50 and group BC75 (P=0.594). The incidence of pruritis was also significantly higher in group BF (33.60%) as compared to both groups BC50 and BC75 (P<0.001) while it was 0.00% in both groups BC50 and BC75. No significant difference (P=0.936) was seen in the incidence of vomiting, shivering, dryness of mouth, and sedation between the groups [Table 4]. The quality of surgical anesthesia was excellent in all except one patient in group BF (0.03%). In this patient, there was no effect of spinal anesthesia. So, GA was given and she was excluded from the study. None of the other patients required any supplemental sedative or analgesic. There were no differences in neonatal outcome [Table 5].

Table 5.

Apgar and umbilical artery blood gas analysis

DISCUSSION

Adding clonidine to IT bupivacaine provides effective and prolonged analgesia with a consequently decreased requirement for supplemental analgesics. The duration of postoperative analgesia was maximum in group BC75 (760.50±284.03 min) followed by group BC50 (360.71±86.51 min) and then in group BF (184.73±68.64 min). These observations suggest that IT clonidine significantly prolongs the duration of pain free period after caesarean delivery in a dose dependent manner.

Our findings are consistent with the findings of Kothari et al. who observed that by increasing the dose of IT bupivacaine, duration of postoperative analgesia was prolonged but with the addition of clonidine to bupivacaine, longer postoperative analgesia occurs at lesser IT dose of bupivacaine (246.21±5.15 min with IT 8 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine +50 μg clonidine vs. 146.0±4.55 min with IT 12.5 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine). The authors also observed that the onset of sensory block occurs faster with higher bupivacaine doses. Consistent with this, in our study, the onset of sensory block was comparable among the three groups because the dose of bupivacaine used for SA was same in three groups. IT clonidine prolongs the duration of bupivacaine induced sensory block. However, the duration is not greatly affected by increasing the dose of clonidine from 50 to 75 μg. The onset time of motor block was comparable in all the three groups (P=0.916), indicating that IT clonidine does not influence the onset of motor block after bupivacaine induced SA. Also, motor recovery is not affected by addition of either 50 or 75 μg clonidine to IT bupivacaine. Kothari et al.[6] also showed that motor recovery is more dependent on dose of bupivacaine rather than on the dose of clonidine. Our results were similar to those of Sethi et al.[7] who found that the mean time from injection to regression of sensory analgesia by two segments was 218 min in clonidine group, which was significantly longer than the duration of 136 min in the control group (P<0.001).

Benhamou and co-workers[8] studied 78 women scheduled for caesarean section, comparing the intraoperative analgesic effect and the time to first analgesic request of the addition of 75 μg clonidine or 75 μg clonidine plus fentanyl to hyperbaric bupivacaine. This study also showed that addition of clonidine prolonged the postoperative pain-free interval. However, addition of fentanyl increased the incidence of sedation and pruritus. We also found that the incidence of pruritus was significantly higher in the BF group compared to the clonidine groups, although the incidence of sedation was the same, unlike that reported by other authors.[6]

Paech and co-workers[9] found that clonidine added to a combination of IT bupivacaine and fentanyl significantly prolongs the duration of analgesia (time to first analgesic request), but did not decrease postoperative morphine consumption or VAS scores. In this four arm trial, the addition of a mixture of morphine (100 μg), clonidine (60-150 μg), and fentanyl (15 μg) to bupivacaine was found to be the optimal combination to improve postoperative pain relief at the expense, however, of sedation and pruritus in 30% of the patients. In all patients and especially in those who received clonidine, drowsiness was seen, which was considered a disadvantage. This side-effect probably resulted from the combination of IT opioid (morphine or fentanyl) and clonidine.

Tuijl et al.[10] investigated the effect of the addition of clonidine (75 μg) to 2.2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative morphine consumption after caesarean section in 106 parturients. They observed that the addition of clonidine (75 μg) to hyperbaric bupivacaine prolongs spinal anesthesia after caesarean section and improves early analgesia, but does not reduce the postoperative morphine consumption during the first 24 h.

The IT clonidine dosage of 50 or 75 μg used in our study had no clinically relevant maternal or neonatal side-effects. Bradycardia in SA, particularly with clonidine as an additive is a worrisome side effect. However, we did not observe any significant fall in heart rate with the addition of IT clonidine. Two patients, one in group BF and one in group BC75 had bradycardia that was easily treated with the use of intravenous atropine. Although the incidence of hypotension was higher in clonidine groups, this apparently was not clinically important, as the total doses of ephedrine used was only slightly higher between the groups. In our study, we observed that the fall in SBP occurred most frequently at either 3 to 6 min after SA or at 5 to 10 min after delivery. The fall in SBP 3 to 6 min after spinal is most probably due to sympatholysis produced by IT bupivacaine and not due to IT clonidine as the hemodynamic effects of clonidine after neuraxial or systemic administration begin within 30 min and reach a maximum within 1-2 hours.[11] The fall in SBP 5 to 10 minutes after delivery coincided with the blood loss caused by placental separation and the use of intravenous oxytocin after delivery of the baby. Clonidine probably augmented the hypotension in two patients (who had onset of hypotension at 25 and 35 min after delivery) and this was easily treatable with intravenous fluids, trendelenburg position and intravenous ephedrine.

In our study, the incidence of nausea was significantly lower in both groups BC50 and BC75 as compared to group BF (P<0.001) while it was comparable between groups BC50 and BC75 (P=0.594). The higher incidence of nausea is probably due to the use of IT fentanyl as all the other possible causes of intraoperative nausea such as hypotension, vagal hyperactivity, visceral pain, and intravenous opioid supplementation were same in the three groups. Kothari et al.[6] also observed that increasing dose of bupivacaine and not clonidine was responsible for the higher incidence of nausea in their patients.

IT clonidine in our study did not produce any pruritis and led to greater maternal satisfaction as compared to IT fentanyl which was responsible for nausea in a significant number of patients in group BF. Although dryness of mouth and sedation are well known side effects of clonidine, we found that dryness of mouth was present equally in patients in three groups (P=0.920). Probably, this dryness of mouth was the result of patient being kept nil orally in the postoperative period and not due to clonidine itself. Sedation is a known side effect of IT clonidine, in the present study, the incidence of sedation was comparable between three groups at all time points (P=0.936). Although IT clonidine caused sedation but the patients were responsive to simple verbal commands. Also the patients were equally sedated in the fentanyl group; this indicated that the sedation seen in our patients postoperatively after caesarean delivery was related more to exhaustion and relief of labor pain rather than to the drug itself.

Clinical implication

To conclude our double blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of addition of IT clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative pain after LSCS has shown that the duration of postoperative analgesia increases significantly on adding 75 μg clonidine to 2 ml of hyperbaric bupivacaine without any increase in maternal side effects. There was no difference in neonatal outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Riley ET, Cohen SE, Macario A, Desai JB, Ratner EF. Spinal versus epidural anesthesia for cesarean section: A comparison of time efficiency, costs, charges, and complications. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:709–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199504000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etches RC, Sandler AN, Daley MD. Respiratory depression and spinal opioids. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:165–85. doi: 10.1007/BF03011441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saxena AK, Arava SE. Current concepts in neuraxial administration of opioids and non-opioids: An overview and future perspectives. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiari A, Lober C, Eisenach JC, Wildling E, Krenn C, Zavrsky A, et al. Analgesic and hemodynamic effects of intrathecal clonidine as a sole analgesic agent during first stage of labor: A dose response study. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:388–96. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filos KS, Goudas LC, Patroni O, Polyzou V. Intrathecal clonidine as a sole analgesic for pain relief after caesarean section. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:267–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothari N, Bogra J, Chaudhary AK. Evaluation of analgesic effects of intrathecal clonidine along with bupivacaine in cesarean section. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:31–5. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi BS, Samuel M, Sreevastava D. Efficacy of analgesic effects of low dose intrathecal clonidine as adjuvant to bupivacaine. Indian J Anaesth. 2007;51:415–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benhamou D, Thorin D, Brichant JF, Dailland P, Milon D, Schneider M. Intrathecal clonidine and fentanyl with hyperbaric bupivacaine improves analgesia during cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:609–13. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199809000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paech MJ, Pavy TJ, Orlikowski CE, Yeo ST, Banks SL, Evans SF, et al. Post-cesarean analgesia with spinal morphine, clonidine, or their combination. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1460–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000111208.08867.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tuijl I, van Klei WA, van der Werff DB, Kalkman CJ. The effect of addition of intrathecal clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative pain and morphine requirements after caesarean section: A randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:365–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenach JC, De Kock M, Klimscha W. Alpha (2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995) Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]