Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Scaling and root planing is one of the most commonly used procedures for the treatment of periodontal diseases. Removal of calculus using conventional hand instruments is incomplete and rather time consuming. In search of more efficient and less difficult instrumentation, investigators have proposed lasers as an alternative or as adjuncts to scaling and root planing. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of erbium doped: Yttirum aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) laser scaling and root planing alone or as an adjunct to hand and ultrasonic instrumentation.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 75 freshly extracted periodontally involved single rooted teeth were collected. Teeth were randomly divided into five treatment groups having 15 teeth each: Hand scaling only, ultrasonic scaling only, Er:YAG laser scaling only, hand scaling + Er:YAG laser scaling and ultrasonic scaling + Er:YAG laser scaling. Specimens were subjected to scanning electron microscopy and photographs were evaluated by three examiners who were blinded to the study. Parameters included were remaining calculus index, loss of tooth substance index, roughness loss of tooth substance index, presence or absence of smear layer, thermal damage and any other morphological damage.

Results:

Er:YAG laser treated specimens showed similar effectiveness in calculus removal to the other test groups whereas tooth substance loss and tooth surface roughness was more on comparison with other groups. Ultrasonic treated specimens showed better results as compared to other groups with different parameters. However, smear layer presence was seen more with hand and ultrasonic groups. Very few laser treated specimens showed thermal damage and morphological change.

Interpretation and Conclusion:

In our study, ultrasonic scaling specimen have shown root surface clean and practically unaltered. On the other hand, hand instrument have produced a plane surface, but removed more tooth structure. The laser treated specimens showed rough surfaces without much residual deposit or any other sign of morphological change.

Keywords: Erbium doped:Yttirum aluminum garnet laser, manual instruments, scaling, root planing, scanning electron microscopy, smear layer, ultrasonic scaler

Introduction

The aim of periodontal treatment is to restore the biological compatibility of periodontally diseased root surfaces for subsequent attachment of periodontal tissues to the treated root surface. During the initial periodontal treatment, debridement of the diseased root surface is usually performed by mechanical scaling and root planing using manual or power-driven instruments. Power-driven instruments such as ultrasonic or air scalers are frequently used for root surface treatment as they render the procedure easy and less stressful for the operator while improving the efficiency of treatment.[1] However, these scalers cause uncomfortable stress to patients from noise and vibration.[1] Furthermore, conventional mechanical debridement using curettes has some advantages, like tactile sense of operator, but it is time-consuming and normally causes bleeding, pain and discomfort to patients. Furthermore, its efficacy of treatment depends strongly on the individual skills of the operator.[2] Complete removal of bacterial deposits and their toxins from the root surface and within the periodontal pockets is not necessarily achieved with conventional mechanical therapy.[3] In addition, access to areas such as furcations, concavities, grooves and distal sites of molars is limited. Therefore, development of novel systems for scaling and root planing as well as further improvement of currently used mechanical instruments, is required.[1]

In search for more efficient and less difficult instrumentation investigators have proposed lasers as alternatives or adjuncts for scaling and root planing.[4,5,6,7,8] As lasers can achieve excellent tissue ablation with strong bactericidal and detoxification effects, they are one of the most promising new technical modalities for non-surgical periodontal treatment. Another advantage of lasers is that they can reach sites that conventional mechanical instrumentation cannot. The adjunctive or alternative use of lasers with conventional tools may facilitate treatment and has the potential to improve healing.[1] Carbon dioxide (CO2) and neodymium doped: Yttirum aluminum garnet (Nd: YAG) lasers, which are commonly used high power lasers, showing excellent soft-tissue ablation capability, accompanied by an adequate hemostatic effect. As such, these lasers have been approved for soft-tissue management in periodontics and oral surgery.[9,10] Since periodontium is composed of various tissues including gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum and alveolar bone, both soft- and hard-tissues are always targeted in the use of lasers as a treatment for periodontal lesions. However, these laser have not been shown to be effective for the treatment of hard-tissues, due to carbonization of these tissues and severe thermal side-effects on the target and surrounding tissues.[11] Therefore, use of these laser systems in periodontal therapy has been limited to soft-tissue treatments, such as gingivectomy and frenectomy.[12] Laser applications to hard tissues, such as the root surface or alveolar bone, have not been proved to be clinically promising for CO2 and Nd: YAG lasers.[13]

Recently, the erbium doped: Yttirum aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) laser has been developed for use in dentistry and the excellent ability of this laser to ablate hard-tissue without producing major thermal side-effects has been demonstrated in various studies.[14] The Er:YAG laser has been currently applied for caries treatment in the clinic, for which very promising results have been reported.[15] This laser has increased the number of possible laser applications in periodontics as well as in restorative dentistry. Based on the promising characteristic of the Er:YAG laser oscillation wavelength (2.94 μm), which is highly absorbed in water and hydroxyapatite,[14] various possible application of the Er:YAG laser for periodontal therapy, such as root surface debridement and soft-tissue and bone tissue surgeries are being investigated.[7,8,16,17]

In the field of periodontics, preparation of the diseased root surface is one of the most promising procedures for Er:YAG laser application. Previous in vitro studies have shown that the Er:YAG laser is effective for ablating subgingival calculus[7] and that this laser has sufficient bactericidal effects on periodontopathic bacteria at a low energy level.[8] In addition, Yamaguchi et al.[18] and Sugi et al.[19] have suggested that Er:YAG laser irradiation might be useful in the elimination of lipopolysaccharides on the diseased root surface. Thus, the Er:YAG laser is thought to have more promising properties for the treatment of periodontally diseased root surfaces than previous laser systems. However, the effectiveness of Er:YAG laser scaling as well as its effect on the root surface, have not yet been evaluated thoroughly, compared to the conventional method.

Hence, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of Er:YAG laser scaling and root planing alone and as an adjunct to hand and ultrasonic instrumentation.

Subjects and Methods

The in vitro study was conducted on 75 freshly extracted human periodontally involved teeth. The teeth selected were single rooted teeth scheduled for extraction due to periodontal disease, based on prior diagnosis. Care taken that the extracted teeth were unaltered by the extraction process with intact root surface. Immediately, after extraction of the teeth they were rinsed in running tap water and then stored in 0.9% NaCl saline until treatment was carried out.

Specimens were then randomly divided into five groups of 15 teeth each corresponding to the combination of instruments to be tested and with a similar amount of proximal calculus as assessed by the naked eye in each group.

Group I : Hand instrumentation using Gracey curettes (no. 1/2, 3/4, 5/6)

Group II : Ultrasonic instrumentation using Dentsply Cavitron unit with Thru flow inserts (TFI) -10 tip.

Group III : Instrumentation with Er:YAG Laser (Fidelis Plus III, FOTONA, Germany) at 80 mJ with 10 pps in non-contact mode

Group IV : Hand instrumentation using Gracey curette no. 1/2, 3/4, 5/6 followed by Er:YAG laser (Fidelis Plus III, FOTONA, Germany) at 60 mJ with 10 pps in non-contact mode

Group V : Ultrasonic instrumentation using DentsplyCavitron with TFI-10 tip followed by Er:YAG laser (Fidelis Plus III, FOTONA, Germany) at 60 mJ with 10 pps in non-contact mode.

A test area was marked on proximal surface of the tooth. Two grooves in faciolingual direction with a distance of 5 mm delineated the test area. Only one trained operator performed all the procedures.

Hand instrumentation was performed using area specific Gracey curettes. Ultrasonic instrumentation was performed using Slimline® cavitron insert.[20] Er:YAG laser scaling and root planing was performed with non-contact mode hand piece kept at a distance of 1 cm from the tooth surface. The beam was focused on the deposit and was continuously moved until deposit was removed. The power setting was fixed at 80 mJ/pulse with 10 Hz frequency for group III and 60 mJ/pulse with 10 Hz frequency for groups IV and V.[21]

The planed tooth surfaces were carefully inspected visually with optimal light and also examined with an explorer (no. 17/23) for a hard, smooth and shiny surface, which were the criteria for adequate treatment.

The specimens after treatment were placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (7.4 pH) for a minimum of 24 h. The teeth were washed and dehydrated through ascending grades of ethyl alcohol (30%, 50%, 70%, 90% and 100%) followed by air drying for 48 h. They were then fixed to scanning electron microscopy (SEM) stubs and sputter coated with 30-40 nm of gold. The specimens were examined using a SEM (JOEL JSM 840 A operating at 15 kV).

The entire test surface of each specimen was scanned initially to obtain a general overview of the surface topography of each specimen. Standardized photomicrographs of the selected sites were obtained at a magnification of ×100 and ×500 for each specimen.

The specimens were then examined for the following parameters:

Presence or absence of smear layer

Remaining calculus index (RCI) (Meyer and Lie, 1977)[22]

Loss of tooth substance index (LTSI)(Meyer and Lie, 1977)[22]

Roughness loss of tooth substance index (RLTSI) (Lie and Lekness, 1985)[23]

Any signs of thermal effects like carbonization or charring in the group treated with Er:YAG laser

Any other morphological changes.

The SEM photographs were interpreted by three examiners who were blinded to the study and the data obtained was then subjected for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as number, percentage and mean ± standard deviation and median scores. Since the treatment effect is assessed on the basis of scores, non-parametric methods were employed for analysis. Kruskal-Walli's analysis of variance was used for multiple group comparisons followed by Mann-Whitney test for group wise comparisons. Agreement between examiners was assessed by kappa measure of agreement. A P value of 0.05 or less was set for statistical significance.

Results

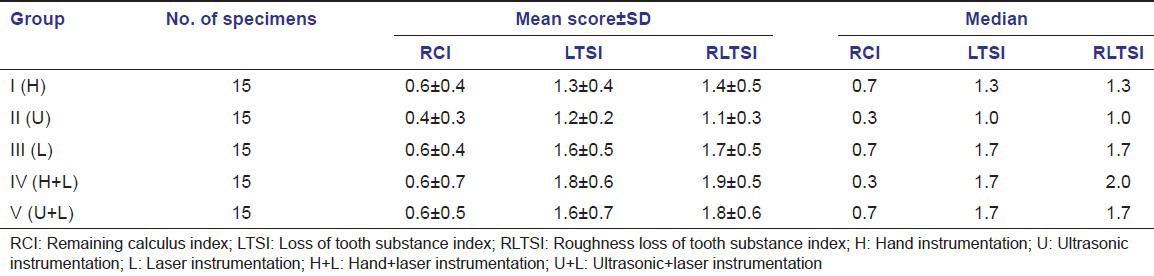

The mean scores of quantitative parameters such as RCI, LTSI and RLTSI are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean scores of quantitative parameters (RCI, LTSI, RLTSI)

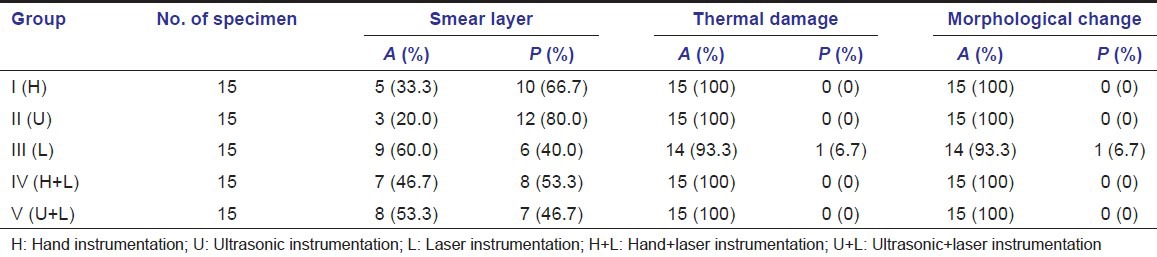

The presence or absence of qualitative parameters such as smear layer, thermal damage and morphological change is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean scores of qualitative parameters (smear layer, thermal damage, morphological change)

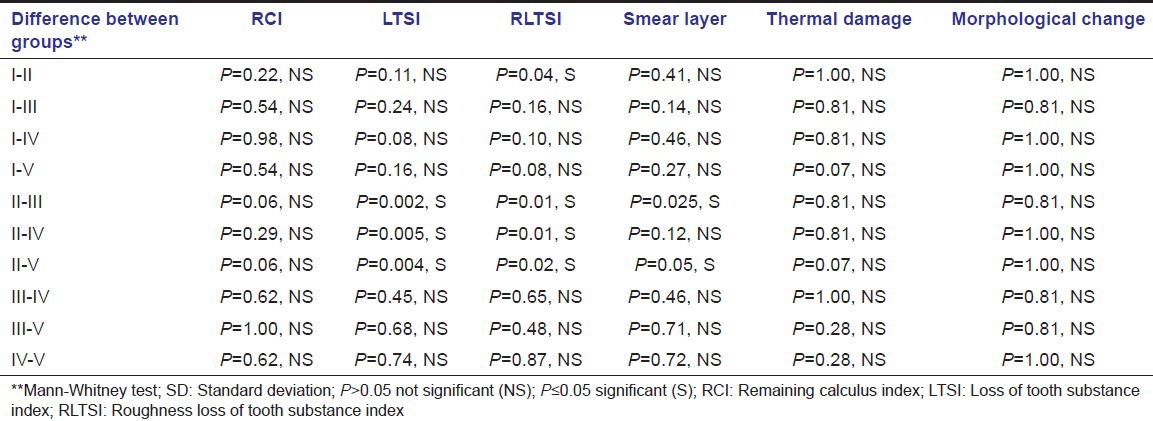

The intergroup comparison between all the parameters is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of both qualitative and quantitative parameters

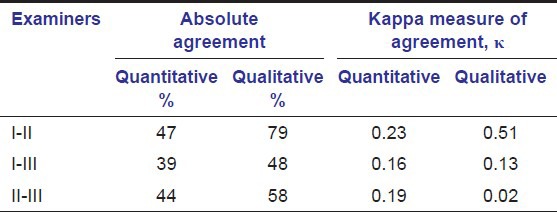

The inter-examiner reliability between all examiners is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Inter-examiner reliability between all examiners

Discussion

Among all lasers used in the field of dentistry, which include CO2, Nd:YAG laser and diode lasers, the Er:YAG laser has been reported to be the most promising laser for periodontal treatment. Its excellent ability to effectively ablate hard-tissue and dental calculus without producing major thermal side-effects to adjacent tissue has been demonstrated in numerous studies.[7,24,25,26] Er:YAG laser irradiation has also been reported to exhibit bactericidal and detoxification effects without producing a smear layer and the laser treated root surface may therefore provide favorable conditions for the attachment of periodontal tissue.[15] Furthermore, the results from controlled clinical trials and case report studies have also indicated that non-surgical periodontal treatment with an Er:YAG laser leads to a significant gain of clinical attachment level.[27,28] This minimally invasive device may allow instrumentation of very deep and narrow pockets without leading to major trauma of the hard and soft-tissues; i.e., removal of tooth substance and increase in gingival recession.[15]

In this study, all the procedures were carried out by one operator, in order to eliminate inter-operator variability and minimize the variables such as stroke length, force and pressure applied during instrumentation.

Evaluation of the amount of remaining calculus and loss of tooth substance was based on visual inspection of standardized micrographs and scoring according to defined criteria. This method obviously is liable to judgments of individual examiners. By comparing the data from the three examiners; however, it became clear that the inter-examiner variability was well within the acceptable range.[23]

Published research concerning the use of lasers for removal of dental plaque, calculus, smear layers and cementum from tooth root surfaces is contradictory.[29,30,31] Such a diversity in reported observations is not surprising given the number of laser wavelengths available, the wide choice of laser parameters and differences in experimental design, which is also a limitation of the study.

In the present study, Fidelis Plus III (FOTONA, Germany) laser unit was used. The laser beam used was a focused one in non-contact mode. The energy output for Er:YAG (2.94 μm) laser alone group was 80 mJ and in other groups in combination with hand and ultrasonic instruments was 60 mJ with 10 pps. The energy output and other parameters were determined based on the results of previous studies.[21,25]

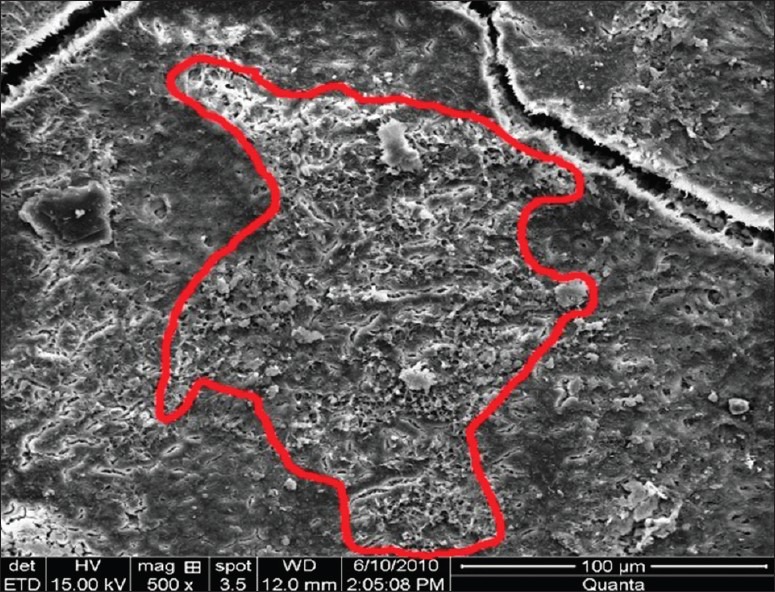

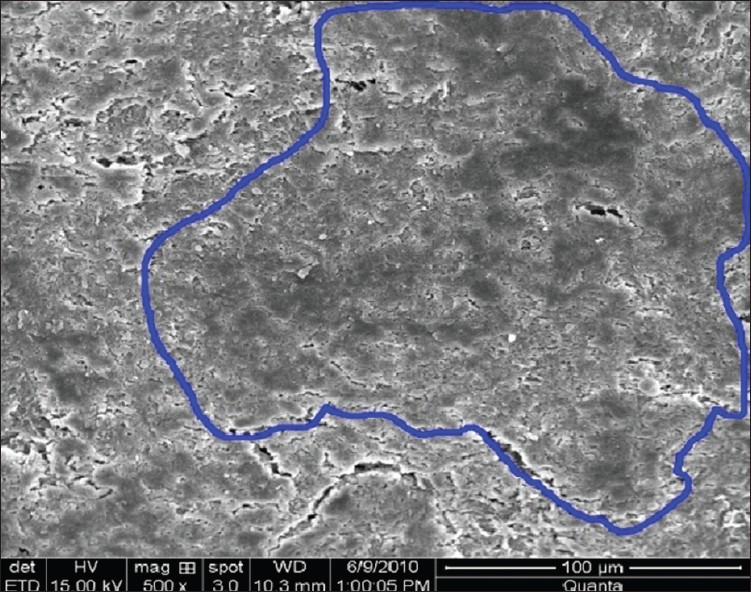

Remaining calculus was easily recognized on the root surfaces, either as patches of varying size localized at random on most of the treated surface or as more continuous areas covering a greater part of the surface [Figures 1 and 2].[10] Higher magnification of areas with remaining calculus demonstrated its irregular morphology representing a marked increase in surface area and alteration of the natural contour of the teeth.[22]

Figure 1.

Remaining calculus index group IV (hand + laser instrumentation) at ×100

Figure 2.

Remaining calculus index group V (ultrasonic + laser instrumentation) at ×500

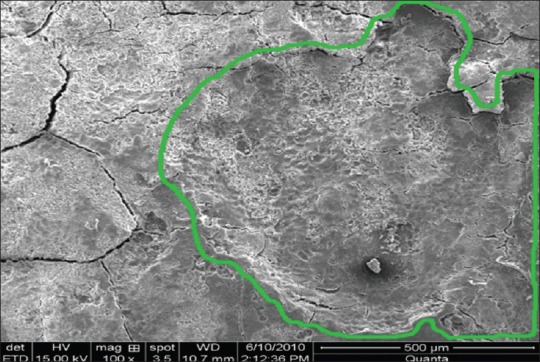

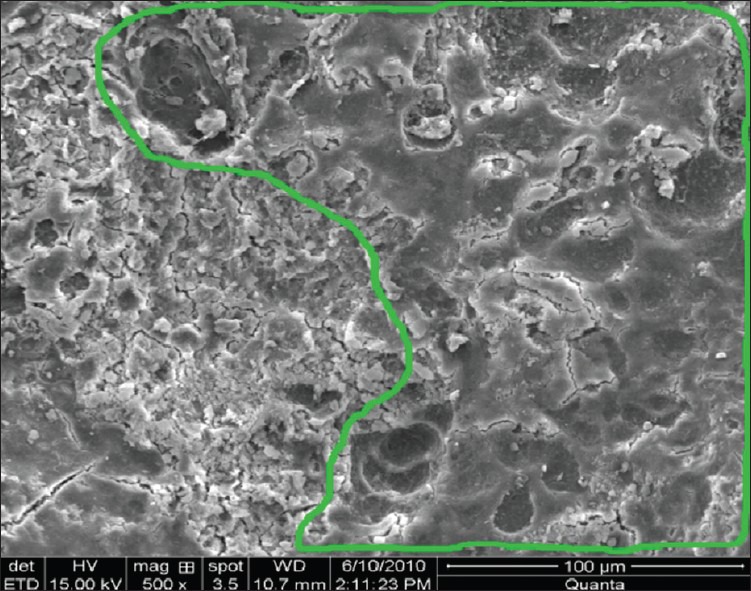

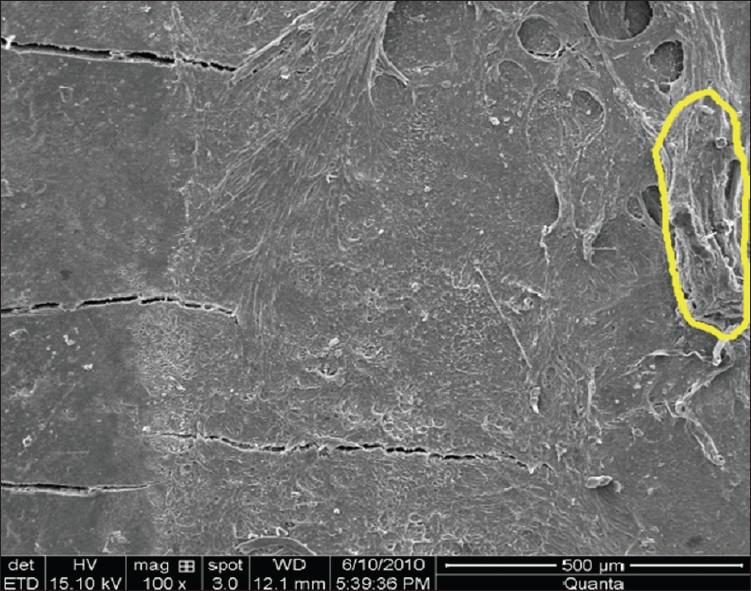

The root surfaces treated by ultrasonic instrumentation showed an undulating surface with a texture, which appeared smooth, but irregular and resembled that seen with hand instrumentation. The primary difference is that the hand instrumented root surface appeared flattened as a result of the removal of tooth structure [Figures 3 and 4]. These results are in contradiction to other reports,[32,33] which have led to the conclusion that ultrasonic scaling may be harmful to the teeth and leaves a roughened surface. The results however are in agreement with those of Schaffer[34] and Stendhe and Schaffer[35] who reported that the root surface of teeth was left smooth and basically unaltered by ultrasonic instrumentation. At higher magnification, the final surface characteristics are merely identical with two types of instrumentation.

Figure 3.

Loss of tooth substance index group I (hand instrumentation) at ×100

Figure 4.

Loss of tooth substance index group I (hand instrumentation) at ×500

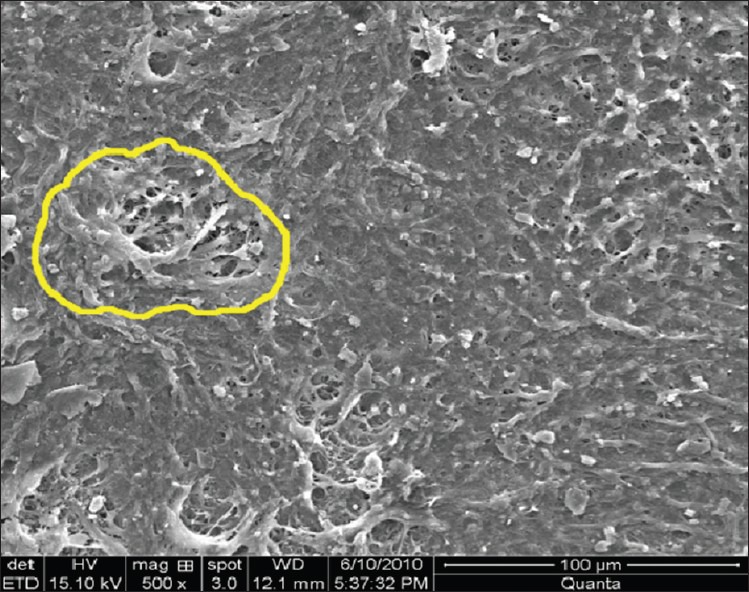

Er:YAG laser ablated not only the calculus, but also the superficial to deep portion of the underlying cementum and that the treated surface had characteristic microstructure resulting from cementum ablation [Figures 5 and 6]. These findings indicate that the Er:YAG laser did not have sufficient selective calculus ablation ability at the irradiation condition used in the present study. In the debridement of the diseased root surface not only the removal of calculus, but also removal of contaminated cementum is required. Therefore, certain amount of cementum ablation during calculus removal using the Er:YAG laser may be clinically acceptable. However, recent studies suggest that pathological changes exist only in the superficial layers of the periodontally diseased surface and therefore deeper layer of cementum should be preserved.[36,37] Under the present irradiation conditions selective calculus elimination using the Er:YAG laser was still difficult and technically dependent. Therefore, careful irradiation performance using the optimal output energy setting was required in order to prevent excessive cementum ablation. Regarding the selective calculus removal, Rechmann et al.[38] recently reported the excellent characteristics of the frequency doubled Alexandrite laser. The Alexandrite laser seems to have a promising characteristic for selective calculus removal. Loss of tooth substance and mild to moderate irregularity was more evident in groups of laser scaling compared to ultrasonic and manual scaling.[13]

Figure 5.

Roughness loss of tooth substance index group V (ultrasonic + laser instrumentation) at ×100

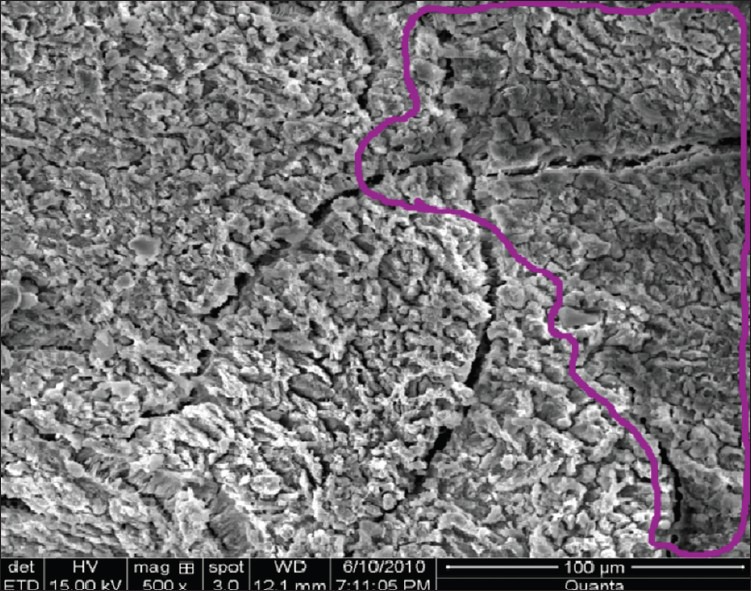

Figure 6.

Roughness loss of tooth substance index group V (ultrasonic + laser instrumentation) at ×500

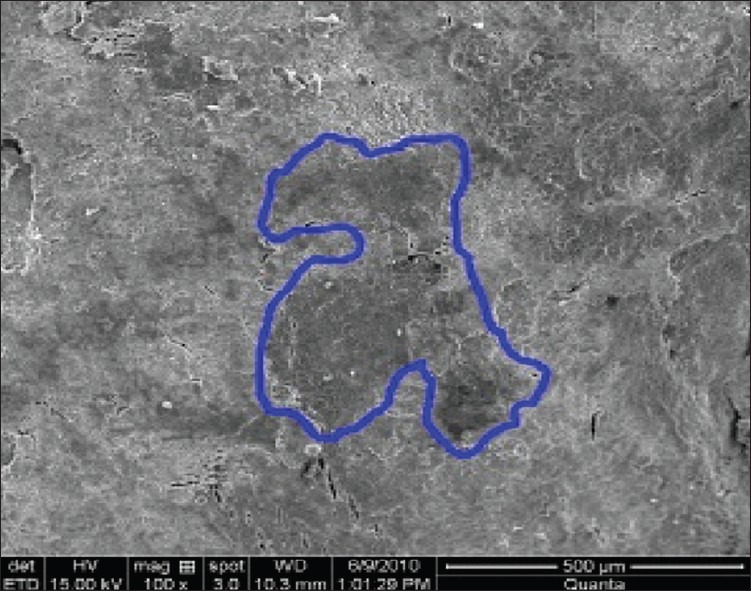

All lased specimens revealed an almost rough surface without residual deposits or any sign of a smear layer formation [Figures 7 and 8]. Regarding this effect, it was speculated that the superficial layer might be highly damaged through both microstructural degradation and thermal denaturation.[13] According to Folwaczny et al.[24] another important histological feature is the presence of roughness in all lased root surfaces presented by Frentzen et al.[39] Keller and Hibst[15] reported the roughness of root surfaces treated with Er:YAG laser as 20-25 μm thick. This roughness seems to be compatible with healing results[40] as the micromorphology of Er:YAG laser treated root surfaces is quite compatible to the surface structure achieved by conventional treatment and conditioning with citric acid or ethylene diaminete traacetic acid.[27] According to other authors,[27] the surface morphology obtained with Er:YAG laser might, in theory, also promote the colonization of fibroblasts.

Figure 7.

Smear layer group III (laser instrumentation) at ×100

Figure 8.

Smear layer group III (laser instrumentation) at ×500

The damage caused to the tooth by lasers differs markedly from the root surface obtained after treatment with conventional root planing.[23,41] The craters observed on the cementum surface following laser exposure could well represent a niche for plaque retention. The biological and clinical significance of these defects is not known. However, one can assume that laser irradiated surface would need additional instrumentation to remove irregularities on the root surface. As Morlock et al.[31] noted, the alterations resulting from laser exposure may increase the instrumentation time necessary to achieve a clinically acceptable root surface. In our study, though time required was more for the treatment of laser specimens in combination with hand and ultrasonic scaling, but the combined laser treated specimen did not prove beneficial with that compared to hand and ultrasonic scaled specimens.

It is also possible that laser irradiation could alter the biocompatibility of the cementum surface for fibroblasts. Our observations indicate that there was a layer of damaged tissue within the cementum where structural changes had occurred. It is known that the cementum contains type-I collagen and non-collagenous proteins, such as bone phosphoprotein and osteocalcin.[33] Osteocalcin is one of the extracellular matrix proteins of bone, which has been implicated in calcification. It is possible that within the damaged layer we observed, protein components of cementum may have been affected by the Er:YAG laser energy. The craters and the irregular surface of the lesion could represent a niche for plaque retention. The alterations in the structure of the cementum might also affect connective tissue attachment during the healing and regenerative procedures. Further, investigation on the biological effects of Er:YAG laser is needed before introducing this technology in periodontal therapy.

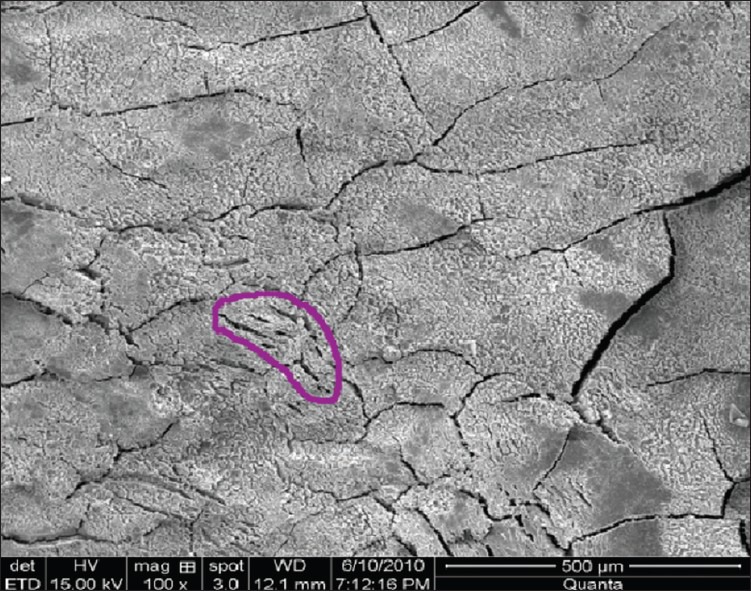

In our study, very few specimens were observed with thermal damage [Figures 9 and 10]. However, our observations did not show signs of melting, charring, carbonization and formation of smear layer on the root surface. As per the previous studies[42,25] these changes are usually associated with Nd:YAG and Co2 irradiation.

Figure 9.

Thermal damage group IV (hand + laser instrumentation) at ×100

Figure 10.

Thermal damage group IV (hand + laser instrumentation) at ×500

A concept of “micro-explosions” has been proposed in order to explain the mechanism of hard-tissue ablation by Er:YAG laser.[15] Er:YAG laser has an energy wavelength peak of 2.94 μm that corresponds to the absorption coefficient of water. Water evaporates forming steam within the tissues. The internal pressure increases until explosion occurs causing destruction of an inorganic substance before the melting point is reached. Furthermore, it has been reported that there is little increase in temperature on the root surface[7] and in the pulp[43] chamber during Er:YAG laser scaling with water irrigation. Thus, the mechanisms of tissue damage caused by Er:YAG laser are probably not reached to thermal effects as with the other types of lasers. It is possible that tissue alterations are due to the micro-explosions associated with water evaporation within the cementum.

Thus, the lack of melting of root surface mineral, lack of charring and presence of microfractures are likely the result of minimal heat absorption by collateral tissues and are consistent with micro explosive events.[43]

Conclusion

In this study, the ultrasonic scalers are found to be efficient and economically favorable alternative to hand only, laser and combination of lasers with hand and ultrasonic instruments in the treatment of periodontally diseased root surface. Ultrasonic scaling reveals root surface clean and practically unaltered. Hand instruments on the other hand removed more tooth structure; however, it produced a planed surface. The lased specimens revealed an almost rough surface without much residual deposits or any other significant sign of thermal damage or morphological change. However, lasers had the accessibility to the treatment sites compared with conventional and mechanical instrumentation. However, there are no clear trends that demonstrate superiority of the laser as an alternative or as an adjunctive to combination to conventional mechanical debridement.

Further, clinical and histological studies evaluating periodontal healing following non-surgical treatment of periodontal lesions using lasers need to be performed to assess the value of lasers in debridement of microbial deposits on root surfaces.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Aoki A, Sasaki KM, Watanabe H, Ishikawa I. Lasers in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2004;36:59–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moghare Abed A, Tawakkoli M, Dehchenari MA, Gutknecht N, Mir M. A comparative SEM study between hand instrument and Er:YAG laser scaling and root planing. Lasers Med Sci. 2007;22:25–9. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0413-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adriaens PA, Edwards CA, De Boever JA, Loesche WJ. Ultrastructural observations on bacterial invasion in cementum and radicular dentin of periodontally diseased human teeth. J Periodontol. 1988;59:493–503. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.8.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eberhard J, Ehlers H, Falk W, Açil Y, Albers HK, Jepsen S. Efficacy of subgingival calculus removal with Er:YAG laser compared to mechanical debridement: An in situ study. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:511–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz F, Sculean A, Berakdar M, Georg T, Reich E, Becker J. Periodontal treatment with an Er:YAG laser or scaling and root planing. A 2-year follow-up split-mouth study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:590–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz F, Sculean A, Georg T, Reich E. Periodontal treatment with an Er:YAG laser compared to scaling and root planing. A controlled clinical study. J Periodontol. 2001;72:361–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki A, Ando Y, Watanabe H, Ishikawa I. In vitro studies on laser scaling of subgingival calculus with an erbium: YAG laser. J Periodontol. 1994;65:1097–106. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.12.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ando Y, Aoki A, Watanabe H, Ishikawa I. Bactericidal effect of erbium YAG laser on periodontopathic bacteria. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;19:190–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)19:2<190::AID-LSM11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White JM, Goodis HE, Rose CL. Use of the pulsed Nd: YAG laser for intraoral soft tissue surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:455–61. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900110511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pick RM, Colvard MD. Current status of lasers in soft tissue dental surgery. J Periodontol. 1993;64:589–602. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossman JA, Cobb CM. Lasers in periodontal therapy. Periodontal 2000. 1995;9:150–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Lasers in periodontics (position paper) J Periodontol. 1996;67:826–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki A, Miura M, Akiyama F, Nakagawa N, Tanaka J, Oda S, et al. In vitro evaluation of Er:YAG laser scaling of subgingival calculus in comparison with ultrasonic scaling. J Periodontal Res. 2000;35:266–77. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035005266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wigdor HA, Walsh JT, Jr, Featherstone JD, Visuri SR, Fried D, Waldvogel JL. Lasers in dentistry. Lasers Surg Med. 1995;16:103–33. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller U, Hibst R. Effects of Er:YAG laser in caries treatment: A clinical pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 1997;20:32–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1997)20:1<32::aid-lsm5>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe H, Ishikawa I, Suzuki M, Hasegawa K. Clinical assessments of the erbium: YAG laser for soft tissue surgery and scaling. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1996;14:67–75. doi: 10.1089/clm.1996.14.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wantabe H, Yoshino T, Aoki A, Ishikawa I. Wound healing after irradiation of bone tissues by Er:YAG laser. Proc SPIE. 1997;2973:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi H, Kobayashi K, Osada R, Sakuraba E, Nomura T, Arai T, et al. Effects of irradiation of an erbium: YAG laser on root surfaces. J Periodontol. 1997;68:1151–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.12.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugi D, Fukuda M, Minoura S, Yamada Y, Tako J, Miwa K, et al. Effects of irradiation of Er:YAG laser on quantity of endotoxin and microhardness of surface in exposed root after removal of calculus. Jpn J Conserv Dent. 1998;41:1009–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pattinson AM, Pattinson GL. Scaling and root planing. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America: Saunders; 2006. pp. 749–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crespi R, Romanos GE, Barone A, Sculean A, Covani U. Er:YAG laser in defocused mode for scaling of periodontally involved root surfaces: An in vitro pilot study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:686–90. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer K, Lie T. Root surface roughness in response to periodontal instrumentation studied by combined use of microroughness measurements and scanning electron microscopy. J Clin Periodontol. 1977;4:77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1977.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lie T, Leknes KN. Evaluation of the effect on root surfaces of air turbine scalers and ultrasonic instrumentation. J Periodontol. 1985;56:522–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.9.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folwaczny M, Mehl A, Haffner C, Benz C, Hickel R. Root substance removal with Er:YAG laser radiation at different parameters using a new delivery system. J Periodontol. 2000;71:147–55. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaspirc B, Skaleric U. Morphology, chemical structure and diffusion processes of root surface after Er:YAG and Nd: YAG laser irradiation. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:508–16. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028006508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasaki KM, Aoki A, Ichinose S, Ishikawa I. Morphological analysis of cementum and root dentin after Er:YAG laser irradiation. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;31:79–85. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarz F, Pütz N, Georg T, Reich E. Effect of an Er:YAG laser on periodontally involved root surfaces: An in vivo and in vitro SEM comparison. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;29:328–35. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz F, Sculean A, Berakdar M, Georg T, Reich E, Becker J. Clinical evaluation of an Er:YAG laser combined with scaling and root planing for non-surgical periodontal treatment. A controlled, prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:26–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tewfik HM, Garnick JJ, Schuster GS, Sharawy MM. Structural and functional changes of cementum surface following exposure to a modified Nd: YAG laser. J Periodontol. 1994;65:297–302. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito K, Nishikata J, Murai S. Effects of Nd:YAG laser radiation on removal of a root surface smear layer after root planing: A scanning electron microscopic study. J Periodontol. 1993;64:547–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morlock BJ, Pippin DJ, Cobb CM, Killoy WJ, Rapley JW. The effect of Nd:YAG laser exposure on root surfaces when used as an adjunct to root planing: An in vitro study. J Periodontol. 1992;63:637–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerry GJ. Roughness of root surfaces after use of ultrasonic instruments and hand curettes. J Periodontol. 1967;38:340–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belting CM, Spjut PJ. Effects of high-speed periodontal instruments on the root surface during subgingival calculus removal. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;69:578–84. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scahffer EM. Objective evaluation of ultrasonic versus hand instrumentation in periodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1964;8:165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stendhe FW, Schaffer EM. A comparison of ultrasonic and hand scaling. J Periodontol. 1961;32:312–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakib NM, Bissada NF, Simmelink JW, Goldstine SN. Endotoxin penetration into root cementum of periodontally healthy and diseased human teeth. J Periodontol. 1982;53:368–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.6.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukazawa E, Nishimura K. Superficial cemental curettage: Its efficacy in promoting improved cellular attachment on human root surfaces previously damaged by periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:168–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rechmann P, Henning TH. Selective ablation of sub and supragingival calculus with a frequency-doubled Alexandrite laser. Proc SPIE. 1995;2394:203–10. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frentzen M, Braun A, Aniol D. Er:YAG laser scaling of diseased root surfaces. J Periodontol. 2002;73:524–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.5.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pameijer CH, Stallard RE, Hiep N. Surface characteristics of teeth following periodontal instrumentation: A scanning electron microscope study. J Periodontol. 1972;43:628–33. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.10.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theodoro LH, Haypek P, Bachmann L, Garcia VG, Sampaio JE, Zezell DM, et al. Effect of Er:YAG and diode laser irradiation on the root surface: Morphological and thermal analysis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:838–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israel M, Cobb CM, Rossmann JA, Spencer P. The effects of CO2, Nd: YAG and Er:YAG lasers with and without surface coolant on tooth root surfaces. An in vitro study. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visuri SR, Walsh JT, Jr, Wigdor HA. Erbium laser ablation of dental hard tissue: Effect of water cooling. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;18:294–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)18:3<294::AID-LSM11>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]