Abstract

Objectives

To define the incidence of stent thrombosis (ST) and/or AMI (ST/AMI) associated with temporary or permanent suspension of dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) after coronary drug eluting stent (DES) implantation in ‘real-world’ patients, and additional factors influencing these events.

Background

Adherence to DAPT is critical for avoiding ST following DES implantation. However, the outcomes of patients undergoing anti-platelet therapy withdrawal following DES implantation remain to be clearly described.

Methods

Patients receiving DES from 05/01/2003 to 05/01/2008 were identified from a single-center registry. Complete follow-up data were available for 5681 patients (67% male, age 66±11 years, duration 1108±446 days) who were included in this analysis.

Results

Uninterrupted DAPT was maintained in 4070/5681 (71.6%) patients, with an annual ST/AMI rate of 0.43%. Anti-platelet therapy was commonly ceased for gastrointestinal-related issues, dental procedures or non-cardiac/non-gastrointestinal surgery. Temporary DAPT suspension occurred in 593/5681 (10.4%) patients for 17.6±74.1 days, with 6/593 (1.0%) experiencing ST/AMI during this period. Of patients permanently ceasing aspirin (n=187, mean 338±411 days post-stenting), clopidogrel (n=713, mean 614±375 days) or both agents (n=118, mean 459±408 days), ST/AMI was uncommon with an annual rate of 0.1–0.2%. Overall, independent predictors of ST/AMI were unstable initial presentation, uninterrupted DAPT and lower left ventricular ejection fraction. Factors predicting uninterrupted DAPT included diabetes, unstable presentation, prior MI, left main coronary PCI and multi-vessel coronary disease.

Conclusions

In real-world practice, rates of ST/AMI following DES implantation are low, but not insignificant, following aspirin and/or clopidogrel cessation. Use of uninterrupted DAPT appears more common in high-risk patients.

Keywords: aspirin, clopidogrel, PCI, DAPT, stent thrombosis, Drug eluting stent, myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Stent thrombosis (ST) is a devastating complication following coronary drug eluting stent (DES) implantation. Best estimates suggest cumulative long-term ST rates for DES ranging from 1.2 – 3.3% at 4 years,1–5 but that ST continues to occur several years after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at an annual rate of 0.4 – 0.6%.2,6 Multiple factors predispose towards DES thrombosis, including characteristics related to the patient (comorbidities, medication compliance, aspirin and/or clopidogrel sensitivity),7–9 stent (length, diameter, re-endothelialization),10 stent deployment (apposition) and lesion (length, diameter, bifurcation).7,11–12 Of these, non-adherence to anti-platelet therapy is of particular importance.13 Current (2011) guidelines recommend that following PCI with DES patients should receive aspirin 81 mg daily indefinitely, while clopidogrel 75 mg daily should be given for at least 12 months if patients are not at high risk of bleeding.14

Beyond these guidelines, appropriate data that might be used to guide the optimal long-term duration of dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT; aspirin + clopidogrel) are scarce.15 Speculation that indefinite DAPT may be of benefit arose with the PCI-CURE sub-study in 2001, which showed a continued divergence of survival curves at 12 months in those treated with DAPT versus aspirin + placebo following DES implantation for non ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome.16 Other studies have since reinforced17–18 and refuted1,8,19–21 the benefits of DAPT beyond 6 – 12 months after DES implantation. Nevertheless it would appear that in contemporary practice, where 47 – 60% of use may be ‘off-label’,22–24 the implantation of DES in complex lesion and patient sub-groups are additional factors that have led many clinicians to favor indefinite DAPT.18 However, the outcomes of patients receiving uninterrupted and indefinite DAPT following PCI with DES are largely unknown, and methods for tracking and defining these outcomes are challenging. Furthermore, a continued area of uncertainty is the management of patients requiring short-term suspension of clopidogrel and/or aspirin. Although an important and not infrequent scenario, the risks associated with short-term suspension of anti-platelet therapy in contemporary patients is unknown.

To gain further insight into the optimal duration of DAPT and clinical outcomes following cessation, we investigated the risk-profile and outcomes of a large, ‘real-world’ cohort of patients receiving DES from a high-volume center.

METHODS

Data source, patient population and clinical definitions

Patients included in this analysis were drawn from a single center, institutional review-board approved prospective interventional cardiology registry. All patients undergoing PCI are entered into this registry within 24 hours of the index intervention. Standardized data elements are collected at baseline including clinical characteristics, procedural details, laboratory data, subsequent in-hospital clinical events and other test results associated with the procedure. After discharge, subjects are routinely contacted and undergo 30-day and 1 year follow-up. For this study an additional long-term telephone and mail survey was performed at 2 – 4 years post-PCI to capture data related to anti-platelet therapy, bleeding events and ST and/or AMI (ST/AMI). Data regarding adherence to anti-platelet therapy was self-reported and determined at phone/mail survey follow-up, while major adverse cardiac events and mortality were ascertained via phone contact with the patient, family, or primary physician. In addition, subsequent hospital records and the social security death index were queried for major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality. The study period extended from 05/01/2003 to 05/01/2008, with complete procedural and clinical follow-up data were available for 5681 patients, which were subsequently used for statistical analysis. Patients with incomplete follow-up data were excluded, however, as the social security death index was queried, patients suffering fatal events were included in this study.

The majority of events were adjudicated prior to the publication of the Academic Research Consortium standardized definitions25 and were as follows: AMI = coronary ischemic syndrome resulting in creatine kinase-MB fraction > 5× upper limit of normal for peri-procedural events, or > 3× upper limit of normal for events occurring after hospital discharge; ST = culprit DES thrombosis confirmed at angiography. Sub-categories of ST (definite, probable and possible) were combined for this analysis. Other definitions included: Chronic renal impairment = pre-procedure serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL; stable angina = anginal symptoms with no change in frequency, duration or intensity of symptoms within 4 weeks of index PCI; unstable angina = onset of new angina, or altered frequency, duration or intensity of chronic angina, with new/changed pattern of angina occurring within 4 weeks of index PCI. Standard definitions were used to define other common clinical scenarios, such as diabetes.26

PCI procedure and anti-platelet therapy

All patients presenting to the catheterization laboratory routinely received 325 mg aspirin > 90 minutes prior to angiography. In clopidogrel naïve patients clopidogrel 300 – 600 mg was administered ‘on-table’ immediately prior to DES implantation. DES were implanted according to best clinical practice. Technical decisions regarding bifurcations, thrombus, calcification, diffuse disease, complex anatomy, stenting of side branches and the adjunctive use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was left to the discretion of the operators. Of all patients, sirolimus eluting DES was implanted in 62%, paclitaxel-eluting in 34% and other DES in 4%. Post-procedure, aspirin was prescribed at 81 – 162 mg/day indefinitely in all subjects. Patients and their physicians were advised to continue clopidogrel for at least 1 year, however, the final decision regarding the duration of clopidogrel therapy was left to the primary referring physician.

Statistical Analysis

Due to low event numbers and to increase statistical power, and also due to complexities of the multiple possible modes of anti-platelet therapy discontinuation, the outcomes of ST and AMI were combined for this analysis.

Multiple group comparisons for categorical variables were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test, while continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey test. Relationships of event incidence to covariables were investigated with univariable regression models. The proportional hazard assumption was checked for all significant univariables; no relevant violations were found.27 Significant univariable predictors at the p ≤ 0.1 level were then entered into the multivariable models. For predictors of ST/AMI, a Cox proportional hazard model was used with a stepwise elimination process.13 For predictors of which patients received uninterrupted DAPT, a stepwise binary logistic regression model was used. Survival analysis was by Kaplan-Meier analysis, with potential between group differences assessed by Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) comparisons. Given the differing lengths of follow-up between patients and to permit unbiased comparisons, Kaplan-Meier analyses were arbitrarily censored at 2000 days after the index PCI. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS/JMP Version 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Unless otherwise stated data are presented as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics for the 5681 patients in this study are presented in Table 1. When grouped according to continuation or cessation of anti-platelet therapies, several differences existed between the patient groups. In particular, diabetic patients and those that received prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery were more likely to receive uninterrupted DAPT. Also, patients receiving Coumadin were more likely to undergo permanent suspension of aspirin, or both aspirin and clopidogrel.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics based on 6 patient groups undergoing cessation of anti-platelet therapy, with a further group receiving uninterrupted DAPT.

| Entire cohort |

Permanent d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel |

Temporary d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel |

Permanent d/c Aspirin |

Temporary d/c Aspirin |

Permanent d/c Clopidogrel |

Temporary d/c Clopidogrel |

Uninterrupted DAPT |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5681 | 118 | 331 | 187 | 54 | 713 | 208 | 4070 | |

| Age (years) | 66 ± 11 | 68 ± 12 | 66 ± 10 | 69 ± 11 | 68 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | 66 ± 11 | 65 ± 12 | <0.0001 |

| Male gender (%) | 67 | 69 | 63 | 61 | 56 | 62 | 72 | 68 | 0.032 |

| Hypertension (%) | 88 | 86 | 88 | 86 | 90 | 87 | 89 | 84 | 0.021 |

| Diabetes (%) | 38 | 39 | 32 | 30 | 37 | 27 | 35 | 41 | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 88 | 86 | 90 | 86 | 89 | 84 | 90 | 89 | 0.0012 |

| Current smoker (%) | 18 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 0.43 |

| Previous CABG (%) | 15 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 0.0041 |

| Chronic renal impairment (%) |

11 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 0.012 |

| LVEF (%) | 54 ± 9 | 54 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 53 ± 11 | 54 ± 10 | 55 ± 8 | 54 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 0.22 |

| Receiving Coumadin (%) |

5 | 13 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| Presenting syndrome | 0.19 | ||||||||

| Stable angina (%) | 57 | 64 | 63 | 57 | 58 | 61 | 56 | 56 | |

| Unstable angina (%) | 34 | 28 | 30 | 30 | 36 | 30 | 36 | 35 | |

| AMI (%) | 9 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

P value represents results of Pearson’s chi-square test or ANOVA for overall differences among groups. d/c discontinuation; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction.

Several differences also existed between the patient groups in terms of angiographic and procedural characteristics. Notably, patients that remained on uninterrupted DAPT had an increased tendency toward multi-vessel coronary artery disease, with a higher number of vessels with > 60% stenosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| Entire cohort (n = 5681) |

Permanent d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel (n = 118) |

Temporary d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel (n = 331) |

Permanent d/c Aspirin (n = 187) |

Temporary d/c Aspirin (n = 54) |

Permanent d/c Clopidogrel (n = 713) |

Temporary d/c Clopidogrel (n = 208) |

Uninterrupted DAPT (n = 4070) |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary vessel | |||||||||

| -LMCA (%) | 3.0 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.08 |

| -LAD (%) | 51 | 42 | 46 | 57 | 57 | 52 | 49 | 51 | 0.10 |

| -LCx (%) | 33 | 36 | 33 | 32 | 26 | 27 | 32 | 35 | 0.005 |

| -RCA (%) | 29 | 29 | 30 | 25 | 30 | 31 | 27 | 29 | 0.80 |

| -IMA (%) | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.31 |

| -SVG (%) | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 0.36 |

| Number of vessels with > 60% stenosis |

1.76 ± 0.79 | 1.71 ± 0.76 | 1.73 ± 0.77 | 1.68 ± 0.75 | 1.68 ± 0.75 | 1.60 ± 0.74 | 1.69 ± 0.79 | 1.81 ± 0.80 | 0.0001 |

| Number of lesions Undergoing intervention at index PCI |

1.51 ± 0.70 | 1.31 ± 0.48 | 1.55 ± 0.71 | 1.53 ± 0.72 | 1.29 ± 0.60 | 1.46 ± 0.67 | 1.49 ± 0.68 | 1.52 ± 0.71 | 0.001 |

| Total lesion length per patient (mm) |

23.4 ± 15.2 | 21.1 ± 13.2 | 23.4 ± 13.7 | 23.2 ± 13.9 | 19.6 ± 11.9 | 22.4 ± 14.1 | 23.4 ± 15.7 | 23.7 ± 15.0 | 0.08 |

| Number of stents per patient |

1.44 ± 0.70 | 1.29 ± 0.54 | 1.45 ± 0.69 | 1.48 ± 0.72 | 1.26 ± 0.48 | 1.42 ± 0.67 | 1.40 ± 0.62 | 1.45 ± 0.68 | 0.05 |

| Bifurcation stenting (%) |

3.8 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 0.19 |

| Re-stenotic lesions (%) |

9.2 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 3.8 | 11.1 | 6.6 | 11.8 | 10 | 0.03 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use (%) |

47 | 39 | 51 | 43 | 37 | 60 | 49 | 45 | 0.0001 |

P value represents results of Pearson’s chi-square test or ANOVA for overall differences among groups. IMA = internal mammary artery; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx = left circumflex coronary artery; LMCA = left main coronary artery; RCA = right coronary artery; SVG = saphenous vein graft.

Reasons for cessation of anti-platelet therapy

Anti-platelet therapy was most commonly suspended for gastrointestinal (GI) issues (bleeding or need for GI procedure such as endoscopy), the need for non-cardiac/GI surgery (e.g. orthopedic procedures, cataract surgery etc.) or for dental procedures (Table 3). The need for cardiac surgery, intolerance unrelated to GI issues and financial/social reasons were less commonly cited as the reason for anti-platelet therapy cessation. However, we are unable to exclude that patients may have under-reported cessation due to financial/social reasons.

Table 3.

Patient-reported reasons for cessation of anti-platelet therapy.

| Permanent d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel (n = 118) |

Temporary d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel (n = 331) |

Permanent d/c Aspirin (n = 187) |

Temporary d/c Aspirin (n = 54) |

Permanent d/c Clopidogrel (n = 713) |

Temporary d/c Clopidogrel (n = 208) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI related (bleeding or need for GI procedure) |

19.5% | 48.4% | 6.4% | 29.6% | 13.9% | 19.6% |

| Non-cardiac/GI surgery – orthopedic, cataract etc. |

4.2% | 56.1% | 10.7% | 27.8% | 8.1% | 33.9% |

| Dental | 0.9% | 29.7% | 4.8% | 20.4% | 5.0% | 20.0% |

| Cardiac surgery | 0.0% | 7.3% | 1.1% | 5.6% | 2.5% | 1.4% |

| Intolerance (unrelated to GI issues) |

8.5% | 3.0% | 1.1% | 5.6% | 8.1% | 6.2% |

| Financial/Social | 7.6% | 2.4% | 0.5% | 3.7% | 2.1% | 6.2% |

| Advised by doctor | 1.7% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.7% | 6.7% |

| Unknown | 61% | 4% | 79% | 28% | 70% | 10% |

GI = gastro-intestinal. Note that some patients gave > 1 reason for anti-platelet cessation, therefore totals exceed 100%.

Clinical outcomes with uninterrupted anti-platelet therapy versus permanent cessation

Mean time to final follow-up was 1108 ± 446 days. A total of 1018 (17.9%) patients permanently ceased aspirin only, clopidogrel only, or both agents, with 4070 (71.6%) patients receiving uninterrupted DAPT throughout the study period (Table 4). Time to cessation differed significantly between the groups, with patients discontinuing aspirin at a mean of 338 days post-PCI, while clopidogrel was discontinued at a mean of 614 days. Annual rates of ST/AMI were generally low. However, we observed that while patients receiving uninterrupted DAPT had an annual ST/AMI rate of 0.43%, those undergoing permanent cessation of all DAPT (aspirin and clopidogrel) had an annual rate of only 0.25% (Table 4). ST/AMI was not observed with cessation of aspirin alone (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of patients undergoing permanent cessation of anti-platelet therapy, or receiving uninterrupted (continuous) DAPT.

| Therapy | N | Time to Cessation (days) |

% patients that d/c therapy < 1 year |

Number of patients with ST or AMI |

Proportion of patients with ST or AMI during study (p = 0.27) |

ST or AMI annual rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel |

118 | 459 ± 408 | 40.9% | 1 | 0.85% | 0.25% |

| Permanent d/c Aspirin |

187 | 338 ± 411 | 69.9% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Permanent d/c Clopidogrel |

713 | 614 ± 375 | 17.5% | 4 | 0.56% | 0.15% |

| Uninterrupted DAPT | 4070 | - | - | 47 | 1.16% | 0.43% |

Groups are mutually exclusive (patients were only assigned to a single group).

Clinical outcomes in patients having temporary suspension of anti-platelet therapy

A total of 593 patients underwent temporary cessation of anti-platelet therapy, with the mean duration of cessation being 17.6 days (Table 5). Of these, 6 patients suffered ST/AMI during the period of cessation (1.01% overall incidence of ST/AMI during temporary cessation), occurring in 4 patients ceasing both aspirin and clopidogrel (1.21% incidence), and 2 patients ceasing clopidogrel only (0.96% incidence) (Table 5). All 6 patients that suffered ST/AMI during temporary cessation were ≥ 14 months post-PCI. ST/AMI was not observed with temporary cessation of aspirin only, and all events occurred after ≥ 5 days of cessation.

Table 5.

Outcomes of patients undergoing temporary cessation of anti-platelet therapy.

| Therapy cessation | N | Number of patients with ST or AMI |

ST or AMI incidence during period of cessation |

Duration of cessation (days) (p < 0.0001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary d/c Aspirin + Clopidogrel |

331 | 4 | 1.21% | 12 ± 41 |

| Temporary d/c Aspirin | 54 | 0 | 0.00% | 8 ± 5 |

| Temporary d/c Clopidogrel | 208 | 2 | 0.96% | 29 ± 113 |

| Total or mean for all patients having temporary d/c anti-platelet therapy |

593 | 6 | 1.01% | 17.6 ± 74.1 |

All patients suffering ST/AMI were ≥ 14 months post-PCI.

Time to death or death/ST/AMI

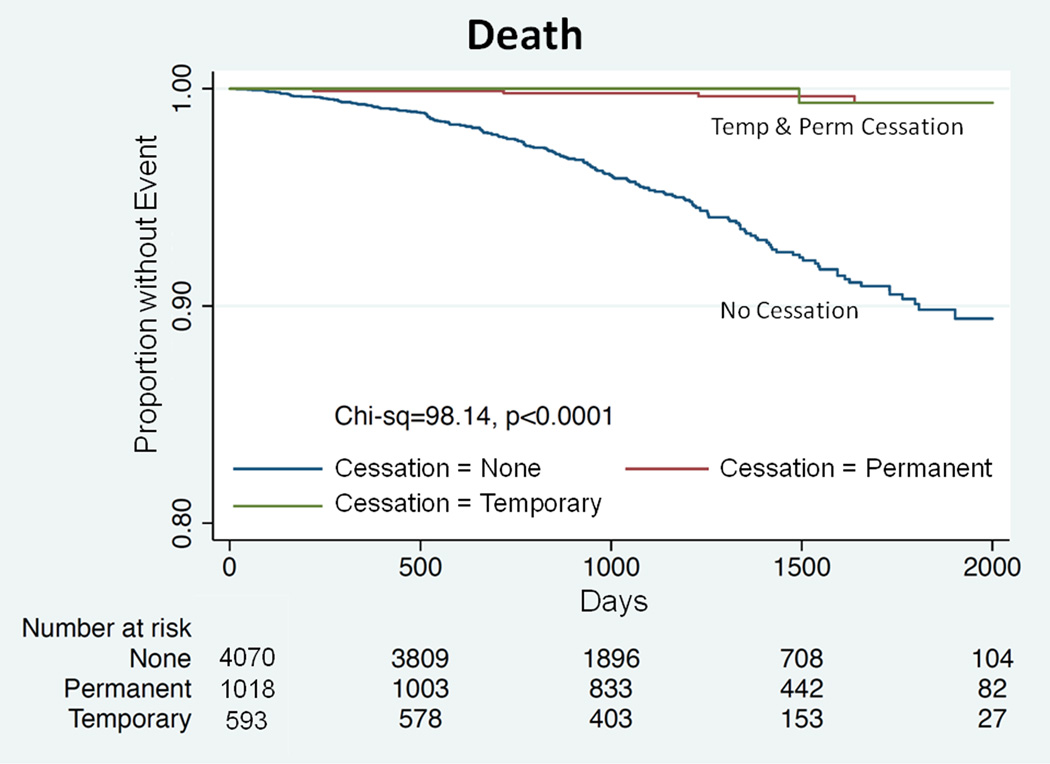

Overall, there were 58 recorded events of ST/AMI (6 during temporary cessation, 5 during permanent cessation, 47 during uninterrupted DAPT). Of these, 17/58 (29.3%) patients died as a result of this event. By Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis and considering all deaths (including those not related to apparent ST/AMI), patients receiving uninterrupted DAPT had higher observed rates of both death (p < 0.0001; Figure 1) and ST/AMI or death (p < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analyses showing cumulative freedom from death. Data for uninterrupted anti-platelet therapy is shown in blue, for temporary cessation in green and for permanent cessation in red. p < 0.0001 for comparison between groups.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analyses showing cumulative freedom from ST/AMI or death. p < 0.0001 for comparison between groups.

Predictors of ST or AMI

Univariable analysis was performed to screen for potential predictors of ST/AMI across all subjects (Table 6). By subsequent multivariable analysis, independent predictors of ST/AMI were: presentation with unstable coronary syndrome or AMI (versus stable presentation) (Hazard ratio [HR] 2.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.33 – 4.02; p = 0.003), receipt of uninterrupted DAPT (HR 2.12, 95% CI 1.15 – 4.21, p = 0.015) and left ventricular ejection fraction (per 1 % increase, HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96 – 1.00, p = 0.052).

Table 6.

Univariable and multivariable analyses for potential predictors of ST and/or AMI (all patients). Significant independent predictors are highlighted in grey.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Chi square |

HR (95% CI) |

p value | Chi square |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

| Presentation with unstable coronary syndrome or AMI (versus stable presentation) |

9.29 | 2.23 (1.32, 3.85) |

0.0023 | 9.08 | 2.27 (1.33, 4.02) |

0.003 |

| Use of uninterrupted DAPT | 8.0 | 2.34 (1.28, 4.64) |

0.0046 | 5.96 | 2.11 (1.15, 4.21) |

0.015 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (per 1 % increase) |

7.62 | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) |

0.006 | 3.79 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) |

0.052 |

| Number of medications at discharge (per additional medication) |

5.15 | 1.17 (1.02, 1.33) |

0.023 | 0.97 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) |

0.33 |

| Total index lesion length (per 1 mm) | 3.49 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) |

0.061 | 0.40 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) |

0.53 |

| Hypertension | 2.8 | 2.16 (0.89, 7.13) |

0.09 | 1.85 | 1.92 (0.77, 6.42) |

0.17 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.75 | 1.91 (0.88, 3.68) |

0.091 | 0.60 | 1.36 (0.59, 2.77) |

0.44 |

| Number of lesions undergoing intervention at index PCI (per lesion) |

2.78 | 1.32 (0.95, 1.78) |

0.095 | 0.48 | 1.17 (0.74, 1.86) |

0.49 |

| Use of Coumadin at discharge | 2.6 | 2.17 (0.83, 4.65) |

0.1 | 0.76 | 1.56 (0.53, 3.69) |

0.38 |

| Prior myocardial Infarction | 2.57 | 1.61 (0.89, 2.76) |

0.11 | - | - | - |

| History of prior CABG | 2.09 | 1.6 (0.83, 2.87) |

0.15 | - | - | - |

| Current smoking | 1.9 | 1.55 (0.82, 2.74) |

0.17 | - | - | - |

| Chronic renal impairment | 1.56 | 1.61 (0.74, 3.12) |

0.21 | - | - | - |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.6 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) |

0.21 | - | - | - |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.59 | 0.65 (0.44, 3.26) |

0.44 | - | - | - |

| Stenting of left main coronary artery | 0.44 | 1.52 (0.37, 4.12) |

0.5 | - | - | - |

| Male gender | 0.32 | 1.18 (0.69, 2.08) |

0.56 | - | - | - |

| Peri-procedural glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use |

0.28 | 0.87 (0.51, 1.47) |

0.60 | - | - | - |

| Multivessel coronary artery disease | 0.23 | 0.88 (0.52, 1.46) |

0.63 | - | - | - |

| Dialysis | 0.66 | 0.66 (0.04, 2.98) |

0.66 | - | - | - |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 0.18 | 1.26 (0.38, 3.06) |

0.66 | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 0.16 | 1.11 (0.65, 1.86) |

0.68 | - | - | - |

| Hemoglobin concentration pre-PCI (per 1 g/dL increase) |

0.06 | 0.98 (0.84, 1.14) |

0.8 | - | - | - |

Note that left ventricular ejection fraction was a borderline significant independent predictor.

Abbreviations not previously defined: HR, hazard ratio.

Predictors of uninterrupted anti-platelet therapy

We further explored possible reasons why the use of uninterrupted DAPT was a predictor of ST/AMI. Following univariable analysis, significant independent predictors of the use of uninterrupted DAPT were: younger age, diabetes, non-use of Coumadin, history of prior myocardial infarction, multivessel coronary artery disease, stenting of the left main coronary artery, hypertension, and initial presentation with unstable coronary syndrome or AMI (Table 7).

Table 7.

Predictors of receiving uninterrupted DAPT.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Chi square |

OR (95% CI) |

p value | Chi square |

OR (95% CI) |

p value |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 84.2 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) |

< 0.0001 | 27.0 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) |

< 0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 55.7 | 1.59 (1.41, 1.79) |

< 0.0001 | 25.6 | 1.43 (1.25, 1.66) |

< 0.0001 |

| Number of medications at discharge (per additional medication) |

25.5 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.12) |

< 0.0001 | 1.1 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) |

0.28 |

| Use of Coumadin at discharge | 14.8 | 0.61 (0.48, 0.79) |

< 0.0001 | 14.5 | 0.60 (0.46, 0.78) |

0.0001 |

| Prior myocardial Infarction | 24.5 | 1.45 (1.23, 1.69) |

< 0.0001 | 15.9 | 1.36 (1.17, 1.58) |

< 0.0001 |

| Multivessel coronary artery disease | 41.4 | 1.39 (1.22, 1.54) |

< 0.0001 | 10.0 | 1.23 (1.08, 1.40) |

0.0016 |

| History of prior CABG | 13.3 | 1.37 (1.15, 1.64) |

0.0003 | 2.0 | 1.14 (0.94, 1.39) |

0.16 |

| Stenting of left main coronary artery | 9.1 | 1.79 (1.22, 2.70) |

0.003 | 5.9 | 1.65 (1.10, 2.54) |

0.015 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8.4 | 1.32 (1.10, 1.56) |

0.003 | 1.6 | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) |

0.21 |

| Male gender | 7.7 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.33) |

0.005 | 3.3 | 1.13 (0.99, 1.28) |

0.069 |

| Hypertension | 10.29 | 1.33 (1.12, 1.59) |

0.012 | 4.0 | 1.21 (1.00, 1.45) |

0.047 |

| Total index lesion length (per 1 mm) | 6.01 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) |

0.015 | 0.4 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) |

0.052 |

| Number of lesions undergoing intervention at index PCI (per lesion) |

5.9 | 1.11 (1.02, 1.22) |

0.018 | 0.2 | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) |

0.62 |

| Presentation with unstable coronary syndrome or AMI (versus stable presentation) |

4.68 | 1.14 (1.01, 1.28) |

0.031 | 4.5 | 1.14 (1.01, 1.28) |

0.034 |

| Chronic renal impairment | 4.7 | 1.23 (1.02, 1.52) |

0.032 | 1.4 | 1.13 (0.92, 1.38) |

0.24 |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 2.63 | 1.23 (0.96, 1.61) |

0.10 | 1.8 | 1.20 (0.92, 1.57) |

0.1823 |

| Current smoking | 2.3 | 1.12 (0.97, 1.32) |

0.13 | - | - | - |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (per 1 % increase) |

2.14 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

0.14 | - | - | - |

| Hemoglobin concentration pre-PCI (per 1 g/dL increase) |

2.08 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.01) |

0.14 | - | - | - |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.4 | 1.15 (0.92, 1.43) |

0.24 | - | - | - |

| Dialysis | 1.04 | 1.22 (0.84, 1.79) |

0.31 | - | - | - |

Abbreviations not previously defined: OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this ‘real-world’ observational study, at a mean of ~3 years following DES implantation a majority (71.6%) of patients remained on uninterrupted DAPT. Further, of those who permanently ceased clopidogrel alone, the mean time of cessation was ~20 months (614 days) post-PCI – appreciably later than the earliest guideline-recommended time (12 months) for clopidogrel cessation.14 Overall, these patients exhibited a high incidence multi-vessel/multi-lesion interventions and significant comorbidities (Table 1). As it is known that these factors generally increase the incidence of ST/AMI,12–13,24,28 we believe these characteristics may have contributed to the tendency for prolonged or indefinite DAPT in these patients. This contention is supported by our finding that the multivariable predictors for the continuation of uninterrupted DAPT could be broadly classified as markers of cardiovascular risk and poorer patient outlook. Consistent with this, survival was significantly worse in patients receiving uninterrupted DAPT (Figure 1).

By binary logistic regression analysis, uninterrupted DAPT was an independent predictor of ST/AMI. This finding is not without precedent21 and prompted a close exploration of our data. We identified that a broad range of factors generally associated with a poorer cardiovascular outlook predicted the use of uninterrupted DAPT. This is consistent with emerging data suggesting that the importance of clinical factors in predicting outcomes after PCI, rather than anatomical lesion characteristics, may have been significantly underestimated.29 Therefore, our paradoxical finding that the use of uninterrupted DAPT was a predictor of ST/AMI appears related to the fact that it was the ‘high-risk’ patients who received this therapy long-term. These data also suggest that primary physicians, at least in our study area, are more inclined to prescribe indefinite DAPT in patients perceived to be at highest risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.18,30 Interestingly, prescribing habits may also be influenced by factors such as perceived risk for bleeding events, as consistent with recent reports we found that younger patients were more likely to receive indefinite DAPT,31 while concomitant use of Coumadin was more likely to be associated with DAPT cessation (Table 7). Also of note, presentation with unstable coronary syndrome or AMI was an additional independent predictor of subsequent ST/AMI. We speculate that this may be related to the fact that within-stent neoatherosclerosis, which is thought to cause late thrombotic events, more commonly develops following stenting of unstable coronary lesions.32

Of the patients that received uninterrupted DAPT, we documented a 1.16% cumulative ST/AMI rate at ~3 years. This rate of ST/AMI in patients receiving uninterrupted DAPT is similar to earlier reports in DES patients in which clopidogrel therapy was generally ceased at 1 – 6 months after index PCI.1–3,6 To the casual observer this might appear as a disappointing result; suggesting that continuation of DAPT beyond 6 – 12 months is futile. However, a closer consideration of these studies reveals that our cohort was at higher intrinsic risk for ST/AMI than the patients enrolled in these reports. For example, in the analysis of Stone et al,3 mean age was ~62 years (our cohort = 66 years), % diabetic subjects was ~25% (our cohort = 38%) and treated lesion length was ~15 mm (our cohort = 23.4 mm). Furthermore, while anti-platelet therapies play an important role, the majority of ST events in prior studies were found to occur in patients still receiving these agents.33 Therefore, our data may indicate that at the discretion of the treating clinician, the indefinite continuation of DAPT in higher risk patients may attenuate the risk for ST/AMI such that it remains similar to lower risk patients who cease this therapy.

Of note, those undergoing temporary suspension of DAPT suffered a relatively high 1.01% incidence of ST/AMI over a mean period of 17.6 days in which these therapies were withheld. We speculate that this relatively high rate of events may have arisen due to the fact that those undergoing temporary cessation frequently had concomitant and unforeseen comorbid issues complicating their clinical situation (e.g. GI bleeding or the need for surgery – see Table 3), which was then compounded by the fact that DAPT was suspended.

A common limitation of studies investigating rates of ST after DES implantation is the inability to precisely adjudicate ST and AMI. Inevitably, an unknown number of events reported as ‘probable’ or ‘possible’ ST will actually be thrombosis/occlusion of a de novo coronary lesion. Therefore, in many ways ours and other similar studies are actually investigating not only the efficacy of anti-platelet therapy to prevent ST, but also the protective value of this therapy for future de novo events. Based on the ‘CURE’ study in patients that suffered non-ST segment elevation AMI, it is known that clopidogrel prevents cardiovascular outcomes outside the context of PCI in these high-risk patients.34 Therefore, it is intuitive that other high-risk groups, such as those with a higher number of diseased coronary vessels or significant comorbidities, might experience a reduced overall incidence of vascular events with extended anti-platelet therapy. We believe these reasons may have led to our observation that patients who permanently stopped aspirin and/or clopidogrel, who were generally at low-risk for cardiovascular events, did so with relative impunity. These observations challenge current guidelines for anti-platelet therapy after PCI with DES, and suggest that consideration be given to tailoring therapy according to the overall patient cardiovascular and ST risk profile.

Other important findings of our work that are of potential clinical relevance include; 1) As previously reported,35 ST/AMI was not observed following PCI with DES when aspirin alone was ceased; 2) Consistent with a recent report,36 common reasons for aspirin and/or clopidogrel suspension were the need for GI or dental procedures, or non-cardiac surgery; 3) ST/AMI did not occur within 5 days of cessation of anti-platelet therapy.

Study limitations

This study was not blinded, randomized or placebo controlled, and confounding and other effects may have influenced our results. Overall ST/AMI event rates were low, which may have introduced bias or statistical error. For this reason ST and AMI were combined as the primary outcome. Finally, a significant number of patients could not recall why aspirin and/or clopidogrel were withdrawn.

Conclusion

In real-world practice, rates of ST/AMI following DES implantation are low, but not insignificant, following aspirin and/or clopidogrel cessation. However, high-risk patients appear more likely to receive indefinite DAPT, which may attenuate their risk for ST/AMI such that it remains similar to lower risk patients who cease this therapy.

Randomized prospective studies are now required to truly determine the optimal long-term duration of specific anti-platelet therapy following PCI with DES,1,17 and the ability to safely interrupt these therapies should an urgent need arise. While our data indicate that prudent clinical management is associated with acceptable outcomes following PCI with DES, they also suggest that future studies should incorporate individualized risk stratification to determine the optimal anti-platelet strategy for a given patient. Risk stratification is now routinely used to determine anticoagulation strategy in patients suffering atrial fibrillation (‘CHADS’ score),37 and we believe a similar approach weighing risk of bleeding events and ST/AMI may be appropriate following DES implantation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Ms. Roja Thapi and our database management team. We thank the staff of the Mount Sinai Hospital catheterization laboratory.

No specific funding or grant was used to fund this study. Jason C. Kovacic is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1K08HL111330-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schulz S, Schuster T, Mehilli J, et al. Stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation: incidence, timing, and relation to discontinuation of clopidogrel therapy over a 4-year period. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2714–2721. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenaweser P, Daemen J, Zwahlen M, et al. Incidence and correlates of drug-eluting stent thrombosis in routine clinical practice. 4-year results from a large 2-institutional cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1134–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG, et al. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, et al. Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1020–1029. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, et al. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: a collaborative network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:937–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, et al. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machecourt J, Danchin N, Lablanche JM, et al. Risk factors for stent thrombosis after implantation of sirolimus-eluting stents in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: the EVASTENT Matched-Cohort Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy P, Bonello L, Torguson R, et al. Temporal relation between Clopidogrel cessation and stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuldiner AR, O'Connell JR, Bliden KP, et al. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy. JAMA. 2009;302:849–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn AV, Joner M, Nakazawa G, et al. Pathological correlates of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis: strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435–2441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuchulakanti PK, Chu WW, Torguson R, et al. Correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation. 2006;113:1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005;293:2126–2130. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farb A, Boam AB. Stent thrombosis redux--the FDA perspective. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:984–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF, et al. Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007;297:159–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.joc60179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butler MJ, Eccleston D, Clark DJ, et al. The effect of intended duration of clopidogrel use on early and late mortality and major adverse cardiac events in patients with drug-eluting stents. Am Heart J. 2009;157:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, Morimoto T, Nakagawa Y, et al. Antiplatelet therapy and stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2009;119:987–995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Airoldi F, Colombo A, Morici N, et al. Incidence and predictors of drug-eluting stent thrombosis during and after discontinuation of thienopyridine treatment. Circulation. 2007;116:745–754. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.686048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SJ, Park DW, Kim YH, et al. Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1374–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maisel WH. Unanswered questions--drug-eluting stents and the risk of late thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:981–984. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beohar N, Davidson CJ, Kip KE, et al. Outcomes and complications associated with off-label and untested use of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2007;297:1992–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.18.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Win HK, Caldera AE, Maresh K, et al. Clinical outcomes and stent thrombosis following off-label use of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2007;297:2001–2009. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.18.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. [Accessed 1/20/2012];Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia. Published 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf.

- 27.Taffs R. Checking the proportional hazard assumption with Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. JMPer Cable (SAS/JMP Newsletter) :18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoye A, Iakovou I, Ge L, et al. Long-term outcomes after stenting of bifurcation lesions with the “crush” technique: predictors of an adverse outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1949–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg S, Sarno G, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. A new tool for the risk stratification of patients with complex coronary artery disease: the Clinical SYNTAX Score. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:317–326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.914051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terpening C. An appraisal of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:51–56. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.070282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boggon R, van Staa TP, Timmis A, et al. Clopidogrel discontinuation after acute coronary syndromes: frequency, predictors and associations with death and myocardial infarction--a hospital registry-primary care linked cohort (MINAP-GPRD) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2376–2386. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakazawa G, Otsuka F, Nakano M, et al. The pathology of neoatherosclerosis in human coronary implants bare-metal and drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1314–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai TT, Nallamothu BK, Bates ER. Letter by Tsai et al regarding article, “correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus- and Paclitaxel-eluting stents”. Circulation. 2006;114:e362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630210. author reply e363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, et al. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation. 2009;119:1634–1642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Marsal JR, Ribera A, et al. Background, incidence, and predictors of antiplatelet therapy discontinuation during the first year after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2010;122:1017–1025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.938290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]