Abstract

Birds are the most diverse living tetrapod group and are a model of large-scale adaptive radiation. Neontological studies suggest a radiation within the avian crown group, long after the origin of flight. However, deep time patterns of bird evolution remain obscure because only limited fossil data have been considered. We analyse cladogenesis and limb evolution on the entire tree of Mesozoic theropods, documenting the dinosaur–bird transition and immediate origins of powered flight. Mesozoic birds inherited constraints on forelimb evolution from non-flying ancestors, and species diversification rates did not accelerate in the earliest flying taxa. However, Early Cretaceous short-tailed birds exhibit both phenotypic release of the hindlimb and increased diversification rates, unparalleled in magnitude at any other time in the first 155 Myr of theropod evolution. Thus, a Cretaceous adaptive radiation of stem-group birds was enabled by restructuring of the terrestrial locomotor module, which represents a key innovation. Our results suggest two phases of radiation in Avialae: with the Cretaceous diversification overwritten by extinctions of stem-group birds at the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary, and subsequent diversification of the crown group. Our findings illustrate the importance of fossil data for understanding the macroevolutionary processes generating modern biodiversity.

Keywords: modularity, adaptive radiation, Mesozoic birds, evolutionary constraints, evolutionary rates

1. Introduction

Adaptive radiations are important drivers of modern biodiversity. In the classic model, invasion of a new adaptive zone is accompanied by rapid rates of both speciation and of phenotypic evolution of functionally important traits [1,2]. Operating at large temporal scales, this process explains, in part, the highly unbalanced distribution of species richness among extant clades [3,4].

Birds (i.e. Avialae) originated approximately 152 Ma from within theropod dinosaurs [5,6]. Today they comprise almost 10 000 species [7]. Outwardly, this seems like a clear example of adaptive radiation driven by a key innovation: powered flight. Indeed, qualitative appraisal of the fossil record suggests adaptive radiation among Mesozoic birds [6]. However, quantitative studies of avian cladogenesis suggest the main burst of speciation postdated the origins of flight by up to 85 Myr, occurring well within the crown group [4,8]. The minimal inclusion of fossil data in these analyses leaves open questions of (i) whether the earliest avialans underwent a significant radiation compared with their non-avian relatives and (ii) whether flight, or related innovations, had any role in promoting speciation and morphological diversification in the earliest birds.

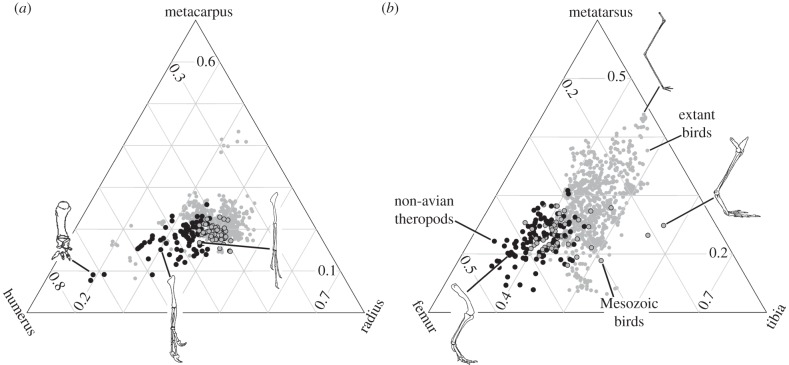

Uniquely among animals, bird flight is controlled primarily by the forelimbs and tail, acting independently of the hindlimb [9]. However, the hindlimb of most theropod dinosaurs, including the earliest (Jurassic) birds, was constrained by its functional linkage to a long, primitive tail [9]. Subsequent dissociation of these modules may have enabled evolutionary versatility of hindlimb anatomy and function, hypothesized as a key innovation of birds [9–11]. Consistent with this hypothesis, modern birds exhibit greater morphological diversity of hindlimbs than Mesozoic theropods (figure 1) [9,12,14], enabling them to exploit diverse ecologies including diving, climbing, wading and perching [9–11]. However, two independent processes of phylogenies evolving in morphospace (i.e. ‘phylomorphospaces’) can generate high morphological disparity [15]: (i) greater amounts of morphological change per unit of phylogenetic distance (equivalent to higher evolutionary rates, when branches are time calibrated) or (ii) relaxation of functional constraints, allowing a greater area of novel morphospace explored per unit of morphological evolution. Of these two possibilities, only elevated rates (or both processes acting together) are consistent with the classic model of adaptive radiation [1,2]. However, the only study to investigate hindlimb evolutionary change (of discrete morphological characters) in Mesozoic birds found no evidence of this [16], and most Mesozoic birds have hindlimb proportions similar to non-avian theropods (figure 1) [12,14].

Figure 1.

Triplots showing within-limb proportions of Mesozoic non-avialan (filled black circles) and avialan theropods (filled grey circles) and extant birds (open grey circles). (a) Forelimb (NMesozoic = 128; Nextant = 639); (b) hindlimb (NMesozoic = 153; Nextant = 708). Line drawings and extant bird values are from refs [12,13]. Line drawings are (left to right) Carnotaurus, Allosaurus, Archaeopteryx (forelimbs), Allosaurus, Phoenicopterus and Hesperornis (hindlimbs).

Numerous recent discoveries of well-preserved Mesozoic birds [6] and a taxon-rich understanding of Mesozoic theropod systematics [17–22] allow us to analyse theropod locomotor evolution and taxonomic diversification in an explicit phylogenetic framework. We compiled a dataset of body proportions and phylogenetic relationships among Mesozoic birds and other theropods. We then tested whether evolutionary rate shifts in fore- and hindlimb proportions are associated with high rates of taxonomic diversification, consistent with hypotheses of adaptive radiation in early birds.

2. Material and methods

Analyses were performed in R v. 2.15.1 [23] using customized code available at DRYAD (datadryad.org/doi:10.5061/dryad.4d0d2). Further details, and our dataset (see electronic supplementary material, dataset S1), are provided in the electronic supplementary material, appendix S1 and on DRYAD. Lengths of the six main limb segments of Mesozoic theropod dinosaurs (including birds) and an informal supertree of 228 taxa (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1) were assembled from specimens and numerous literature sources, including ref. [24]. Polytomies, reflecting phylogenetic uncertainty, were resolved randomly, and branch lengths calibrated according to taxon ages, smoothing zero-length branches by equally sharing duration from the immediately basal non-zero length branch [25]. Results from one such tree are reported in our main text, but similar results were recovered across many randomly resolved versions of our cladogram, and among trees calibrated using several different methods (see electronic supplementary material, appendix S1). All three forelimb measurements are known for 92 taxa included in our tree, and all three hindlimb measurements for 107 taxa.

Phylogenetic principal components analysis (PCA) corrects for phylogenetic non-independence of taxa [26] when determining principal axes of variation [27,28] and was performed on log10-transformed fore- and hindlimb measurements to extract the non-allometric shape component of limb proportions. As expected for length data spanning three orders of magnitude, within which intralimb measurements span less than an order of magnitude, the first principal component axis (PC1) explained more than 95% of the variance. This represents size and size-related (allometric) variation: the eigenvector of PC1 contains coefficients of similar sign and magnitude for all measurements (table 1), and its scores correlate strongly with total limb lengths both using and not using phylogenetic independent contrasts (R2 > 0.99). Analyses of limb shape therefore used only the scores of PC2 and PC3, the eigenvectors of which were robust to taxonomic subsampling and different tree scaling methods (see electronic supplementary material, appendix S1). The PCA scores of ancestral nodes were estimated using maximum likelihood under a Brownian model of evolution with all branch lengths set to 1.0, which is equivalent to squared change parsimony [15,28].

Table 1.

Summary of PCA results based on the first randomly resolved tree, with a root length of 10 Ma.

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| forelimb | |||

| eigenvalue | 0.00584 | 0.00012 | 0.00006 |

| % explained | 97.2 | 1.92 | 0.92 |

| after PC1 | — | 67.6 | 32.4 |

| eigenvector coefficients | |||

| humerus length | −0.57 | −0.47 | 0.67 |

| radius length | −0.56 | −0.37 | −0.74 |

| metacarpus length | −0.59 | 0.80 | 0.05 |

| hindlimb | |||

| eigenvalue | 0.00535 | 0.00009 | 0.00004 |

| % explained | 97.6 | 1.68 | 0.71 |

| after PC1 | — | 70.4 | 29.6 |

| eigenvector coefficients | |||

| femur length | −0.61 | 0.68 | 0.41 |

| tibia length | −0.56 | −0.00 | −0.83 |

| metatarsus length | −0.56 | −0.74 | 0.38 |

A phylomorphospace approach [15] was used to examine patterns of body shape evolution along lineages in a quantitative morphospace by comparing two values among groups: a morphological rate estimate (the ratio of morphological distance to phylogenetic branch duration; morphological distance is the sum of Euclidian distances between ancestor–descendant pairs in a morphospace; electronic supplementary material, appendix S1) and the lineage density (packing of morphological branch length into a morphospace area) [15]. Lineage density was calculated as the total morphological branch length divided by the bounding ellipsoid area in morphospace. Significance of the between-group ratios of morphological rates and lineage densities was established by comparison with the outcomes of 1000 simulations run under a Brownian model of evolution (see electronic supplementary material, appendix S1) on the phylogenetic tree with branch lengths [29].

We also estimated evolutionary rates for each shape axis individually using a Bayesian approach [30], which uses reversible-jump Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling from a distribution of multi-rate models in inverse proportion to their poorness of fit. We implemented this approach over 1 000 000 generations, discarding the first 250 000 as burn-in. The significance of observed rate shifts was assessed using randomization tests [30].

Finally, we used SymmeTREE [31] to survey the tree for significant shifts in rates of lineage diversification, by comparison of tree balance with the expectations of an equal rates Markov diversification process [31]. Significant tree imbalance can arise from an increase in diversification rate at a specified node or from the effects of later extinction in its sister taxon [32]. Thus, we analysed two versions of our cladogram, one extending until the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous and another extending only as far as the Early Cretaceous diversification of pygostylian birds. If both recover the same result, then elevated diversification rates provide the best explanation of any significant tree imbalance [32].

3. Results

(a). Principal components analysis

The second PC axes explain approximately 70% of shape-related variance (see table 1 and electronic supplementary material, appendix S1). For both limbs, opposite signs of the eigenvector coefficients of distal and proximal limb elements indicate that PC2 describes elongation of the metacarpus/metatarsus relative to the humerus/femur. The eigenvector coefficient of the radius length has a similar value to that of the humerus, but that of the tibia is intermediate between the femur and metatarsus. PC3 of the forelimb measurements describes elongation of the radius relative to the humerus, with the metacarpus taking an intermediate eigenvector coefficient. PC3 of the hindlimb measurements describes relative elongation of the tibia compared with the femur and metatarsus. Eigenvector coefficients are robust to taxon subsampling (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2).

(b). Phylomorphospace plots

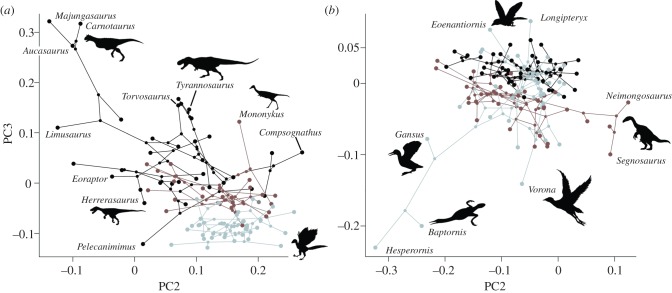

Mesozoic birds, including flightless taxa, have a long metacarpus (high positive PC2) and radius (highly negative PC3) (figure 2a). Various maniraptoran lineages also entered this ‘avialan region’, including basal deinonychosaurs such as Mahakala and Microraptor (suggesting these forelimb proportions may be primitive for Paraves), oviraptorosaurs (e.g. Gigantoraptor) and the alvarezsauroid Haplocheirus. Most non-avialan theropods show intermediate (low, positive) values on both axes. However, some lineages are more different to Avialae, possessing a relatively short metacarpus (negative PC2) in some ornithomimosaurs and early theropods, a short radius (high positive PC3) in tyrannosaurids and alvarezsaurids, or both in some abelisauroids.

Figure 2.

Phylomorphospaces depicting (a) the Mesozoic theropod tree in fore- (N = 92) and (b) hindlimb (N = 107) shape spaces defined by PC2 and PC3 (table 1). Non-maniraptoran lineages are shown in black, non-avialan maniraptorans in dark grey (red) and Avialae in light grey (blue). Silhouettes are illustrative. (Online version in colour.)

Most clades centre on a common region of hindlimb morphospace (figure 2b). However, the spread of data is greater among maniraptorans, among which some enantiornithines have a short tibia compared with the expectations of allometry (high positive PC3) and ornithuromorphs have a long tibia (negative PC3). Each group exhibits a similar range of PC2 values (elongation of the metatarsus compared to the femur), although therizinosauroids have a distinctly short metatarsus (high positive PC2) and the flightless, aquatic hesperornithiforms have a long metatarsus compared with their femur (high negative PC2).

(c). Phylomorphospace parameters

Rates of forelimb evolution in most groups are statistically indistinguishable (at the 5% level) from the expectations of a tree-wide single rate Brownian model (table 2). Although flightless Avialae have slower rates of forelimb evolution than other groups, their small sample size (one lineage) indicates that this result is essentially meaningless. Avialae, Maniraptora and Deinonychosauria occupy significantly less forelimb morphospace area than expected under the Brownian model and have a significantly greater lineage density (packing of morphological distance into morphospace area) than other theropods, implying greater constraint on forelimb morphospace occupation in maniraptorans, including birds.

Table 2.

Statistical significance of phylomorphospace parameter ratios. Numbers are the proportion of replicates simulated under a Brownian evolutionary model for which the ratio between groups was lower than that observed. High values above 0.95 and low values below 0.05 are deemed statistically significant and accompanied by an asterisk (one-tailed probabilities owing to equivalence when reversed). The phylomorphospace is based on the first two shape axes (PC2 and PC3) of a phylogenetic PCA using the first randomly resolved tree with a root length of 10 Ma.

| forelimb rate | area | density | hindlimb rate | area | density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flying Avialae: non-paravian | 0.794 | 0.003* | 0.999* | 1.000* | 0.995* | 0.200 |

| flying Avialae: Deinonychosauria | 0.779 | 0.692 | 0.412 | 0.999* | 0.996* | 0.081 |

| flying Avialae: non-maniraptoran | 0.784 | 0.000* | 1.000* | 1.000* | 1.000* | 0.008* |

| flying Avialae: Maniraptora | 0.765 | 0.348 | 0.725 | 1.000* | 0.987* | 0.239 |

| flying: flightless Avialae | 0.987* | — | — | 0.175 | — | — |

| Deinonychosauria: non-paravian | 0.437 | 0.002* | 0.997* | 0.847 | 0.347 | 0.759 |

| Deinonychosauria: flightless Avialae | 0.979* | — | — | 0.007* | — | — |

| flightless Avialae: non-paravian | 0.018* | — | — | 1.000* | — | — |

| Maniraptora: non-maniraptoran | 0.527 | 0.003* | 0.994* | 0.494 | 0.945 | 0.075 |

| Maniraptora: flightless Avialae | 0.988* | — | — | 0.001* | — | — |

| flightless Avialae: non-maniraptoran | 0.014* | — | — | 0.998* | — | — |

| Pygostylia: non-paravian | 0.778 | 0.005* | 0.998* | 1.000* | 0.994* | 0.164 |

| Pygostylia: other paravians | 0.688 | 0.905 | 0.160 | 0.996* | 0.996* | 0.067 |

| Pygostylia: non-maniraptoran | 0.796 | 0.000* | 1.000* | 1.000* | 1.000* | 0.006* |

| Pygostylia: other maniraptorans | 0.736 | 0.448 | 0.637 | 1.000* | 0.997* | 0.124 |

Avialae exhibit significantly high rates of hindlimb evolution compared with other theropods, including deinonychosaurs and other maniraptorans. Avialae also occupy a significantly larger area of hindlimb morphospace than other theropods, including non-avialan maniraptorans. Avialan and pygostylian hindlimb lineage densities are significantly lower than those of non-maniraptoran theropods. However, although avialan and pygostylian hindlimb lineage densities are lower than expected compared with maniraptorans and deinonychosaurs, the difference is not statistically significant (table 2). Results including only lineages younger than 180 Ma are similar to those from the full time span (see electronic supplementary material, table S2). Results after deletion of 50% of Avialae do not exhibit significantly high hindlimb rates, but do show significantly low lineage density compared with all other theropods, including non-avialan maniraptorans (see electronic supplementary material, tables S4 and S5, and appendix S1).

(d). Tests of multi-rate Brownian motion

Model-averaged posterior distributions of Brownian variance (approx. evolutionary rates [26,33]) for individual PC axes are approximately consistent with our (multi-variate) phylomorphospace approach. Univariate forelimb rates show a few shifts scattered over the tree with little coordinated signal relevant to avian origins (see electronic supplementary material, figures S4 and S5). A shift to slow rates might be localized to the base of the maniraptoran group including therizinosaurs, oviraptorosaurs and paravians, although statistical support for this is negligible (posterior probability = 0.165; p = 0.474n.s.).

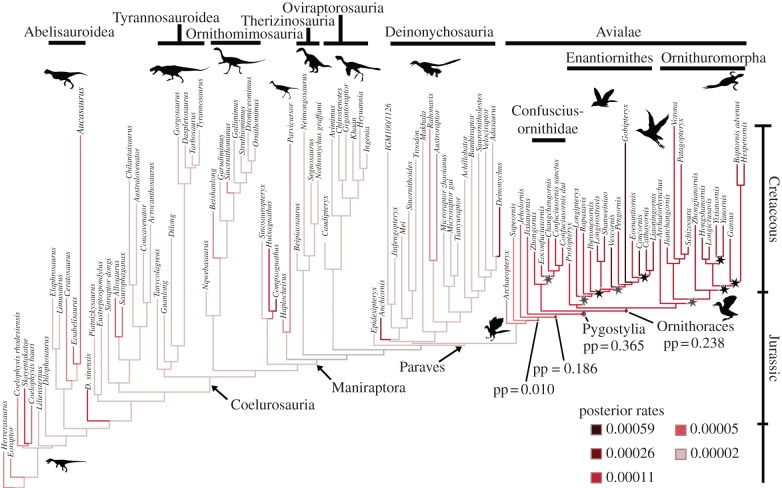

Avialan hindlimb rates are fast. Rapid rates of the metatarsus : femur proportion (hindlimb PC2) are concentrated in Avialae, especially in Ornithurae and some enantiornithines (see electronic supplementary material, figure S6) but are not statistically significant (p = 0.210n.s.). Relative tibia size (hindlimb PC3; figure 3) shows rapid rates in Avialae, but less so among non-pygostylians, and the most likely node for this rate shift is Pygostylia (posterior probability = 0.365; p = 0.015*). Indeed, four pygostylian lineages independently explored the limits of hindlimb morphospace (figure 2b).

Figure 3.

Rate of morphological evolution and cladogenesis. Posterior model-averaged rates (Brownian variance in (log10(mm))/(Myr)) of relative tibia length (hindlimb PC3) in Mesozoic theropods (N = 107) resulting from Bayesian estimation are shown by branch colours, according to the legend. Localized hindlimb PC3 rate shifts are indicated by circles at nodes and their posterior probabilities stated. Stars indicate significant tree imbalance on the complete tree (a pruned version is shown here) according to either Δ1 or Δ2 shift statistics [31], indicating diversification rate shifts among pygostylian birds. Grey stars are shifts recovered using a tree of only Early Cretaceous and younger taxa and black stars are shifts recovered from the tree including all taxa. Taxon ages are independently drawn from a uniform distribution within their substage of occurrence. (Online version in colour.)

(e). Diversification rate shifts

Both sets of tree balance analyses recovered significant (p < 0.05) lineage diversification rate shifts in Early Cretaceous Pygostylia: among basal enantiornithines and ornithurine birds (figure 3). The tree including only Triassic–Early Cretaceous taxa also recovered a shift in Confusciusornithidae. No other significant shifts were detected in the entire tree of Mesozoic theropods.

4. Discussion

(a). Rates and constraint in theropod limb evolution

Extant bird forelimbs occupy greater morphospace area than those of extinct theropods, including Mesozoic birds (figure 1a) [13]. Indeed, Mesozoic birds and other maniraptorans were restricted to small, intensively exploited areas of forelimb morphospace compared with both non-maniraptoran theropods and extant birds (figures 1a, 2a). Maniraptoran forelimbs exhibit high lineage density compared with non-maniraptoran theropods. Thus, evolutionary constraints on forelimb morphospace occupation acted not just on Mesozoic birds but also on flightless maniraptorans and were not imposed purely by the demands of flight. Maniraptorans possess a highly asymmetrical wrist joint, enabling three segment arm folding [34]. This constrains the forelimb segments to approximately equal lengths [13,34], but allows longer and more functionally versatile forelimbs [13], and is associated with ecological diversification in Maniraptora [18]. It may also have protected their pinnate arm feathers from damage [34] and is an exaptation for flight.

Avialan hindlimb morphospace is dominated by pygostylian birds (figures 2a and 3). This suggests that tail abbreviation, rather than powered flight alone, provides the best explanation for enhanced morphospace occupation in birds [9,12,14]. Morphological diversification of the avialan hindlimb was primarily driven by rapid evolutionary rates, especially of relative tibia length. High rates of hindlimb evolution may have continued after the Mesozoic, as extant birds occupy a still greater hindlimb morphospace [12]. Mesozoic avialan hindlimb evolution is also characterized by low lineage density, especially compared with non-maniraptoran theropods. The link between tail reduction and evolutionary release of the hindlimb is confirmed by the eccentric hindlimb proportions of some non-avialan maniraptorans that convergently developed a pygostyle [35,36] (therizinosaurs; figure 2b).

Our results differ from studies of discrete characters (apomorphies), which find little evidence for clade-wide shifts in forelimb [37] or hindlimb [16,37] rates in Avialae or Pygostylia. This difference may be explained by the different data type in our study, and by our consideration of constraints on morphospace exploration. Thus, although evolution across all apomorphies does not support the ‘pectoral early-pelvic late’ hypothesis [38], key characters of forelimb function (relative segment length and wrist mobility [13,34]) evolved before those facilitating hindlimb diversification (flight and an abbreviated tail [9]) and both had major impacts on subsequent limb evolution.

(b). Adaptive radiation in Early Cretaceous birds

Two of our results suggest that evolutionary versatility of the hindlimb was a key innovation driving adaptive radiation in Early Cretaceous pygostylian birds: (i) accelerated rates of evolution in hindlimb proportions, an ecologically important trait [9,12,14] and (ii) significant tree imbalance indicating increased cladogenesis in Pygostylia. Adaptive radiation in Pygostylia, rather than in flying birds as a whole, is consistent with hypotheses of musculoskeletal evolution during the dinosaur–bird transition [9–11]. Diverse cranial specializations also suggest adaptive radiation in Early Cretaceous pygostylians [6,39], although cranial data have not been analysed quantitatively.

Apparent rapid evolutionary rates in birds could result from their substantially smaller body sizes and faster generation times compared with most other theropods [40] or from the generally short branch durations estimated among early Avialae (figure 3; see discussion in the electronic supplementary material, appendix S1). However, we can conservatively say that the difference in hindlimb rates between avialan and non-avialan theropods is substantially greater than that for the forelimbs, and differences in body size, generation time and tree structure cannot explain this observation.

Topological methods to evaluate diversification rate shifts, such as SymmeTREE, can only be applied inexactly to trees including fossil taxa, and this approach remains underdeveloped [32,41]. Arguably, the abundance of small maniraptoran fossils, including avialans, in a single Early Cretaceous Lagerstätte, the Jehol Biota of China [42] could have generated the observed diversification rate shifts in Pygostylia. However, the absence of comparable rate shifts in non-pygostylian maniraptorans, which are also well sampled from the Jehol, gives us confidence that a genuine taxonomic radiation of birds occurred in the Early Cretaceous.

(c). A two-phase model of avialan adaptive radiation

Until now, attempts to explain bird diversity focused on the distal product of their radiation, by predominantly considering extant birds, which live more than 150 Myr after Archaeopteryx [4,8,12]. These studies suggest a radiation within the crown group. The avian crown group is exceptionally speciose and morphologically disparate, for example in their breadth of morphospace occupation [13]. We do not dispute that this reflects a real evolutionary radiation. However, we do find quantitative evidence for an adaptive radiation of Mesozoic stem-group birds [6,43] that predates the crown radiation by at least 30 Myr.

The Mesozoic fossil record documents an early time in avialan history, during which extinctions, climatic fluctuations and a Cenozoic radiation may not yet have overwritten the signals of initial diversification. Mesozoic birds encompassed less morphological and ecological diversity than modern birds and had diversified for substantially less time than their non-avian theropod relatives. Despite this, we have shown that processes capable of generating high taxonomic and morphological diversity were functioning early on the avian stem lineage. Elevated rates of lineage diversification were coincident with high evolutionary rates of ecologically important traits. This is strong evidence for radiation driven by invasion of a novel adaptive zone or the appearance of a key innovation.

(d). Fossil data aids macroevolutionary inference

Because of the richness of neontological datasets, much attention has focused on the radiations that gave rise to extant diversity [2,4,7]. However, there are reasons to be cautious about ‘extant-only’ analyses. First, extinction is an important contributor to patterns of extant species richness [4,44,45] and can seriously bias inferences from neontological datasets [32,46]. Second, the absence of data on extinct morphologies reduces the power of modelling approaches to detect non-Brownian modes of trait evolution [47], and morphological rates along long, unsampled branches tend to be underestimated [48,49].

Abrupt mass extinction at the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary resulted in extinction of the most diverse Mesozoic bird group, Enantiornithes, as well as many basal ornithurines [50], leading to a profound loss of neontological data on the first three-fifths of bird evolution. When fossil data are analysed, a more nuanced picture emerges. Our results emphasize the importance of fossil data when evaluating hypotheses of ancient adaptive radiations and their role in shaping modern diversity.

Acknowledgements

R.B.J.B. wishes to thank B. Sidlauskas, D. W. Bapst and G. T. Lloyd for discussions, and K. Middleton, S. Gatesy, D. Evans and N. Campione for data sharing. J.N.C. wishes to thank M. Carrano, P. J. Currie, D. W. E. Hone and C. Sullivan for discussion and data sharing. R. B. Irmis, H. C. E. Larsson and an anonymous reviewer provided comments that improved the manuscript.

Funding statement

J.N.C.'s participation in this research was supported by the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, the National Research Foundation/Department of Science and Technology's Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences at the University of the Witwatersrand and the Richard Gilder Graduate School at the American Museum of Natural History via a Kalbfleisch Fellowship and Gerstner Scholarship.

References

- 1.Simpson GG. 1953. The major features of evolution. New York, NY: Columbia University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schluter D. 2000. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mooers AO, Heard SB. 1997. Inferring evolutionary process from phylogenetic tree shape. Q. Rev. Biol. 72, 31–54 (doi:10.1086/419657) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfaro ME, Santini F, Brock C, Alamillo H, Dornburg A, Rabosky DL, Carnevale G, Harmon LJ. 2009. Nine exceptional radiations plus high turnover explain species diversity in jawed vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13 410–13 414 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0811087106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauthier J. 1986. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. Mem. Calif. Acad. Sci. 8, 1–56 [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Connor JK, Chiappe LM, Bell A. 2011. Pre-modern birds: avian divergences in the Mesozoic. In Living dinosaurs: the evolutionary history of modern birds (eds Dyke G, Kaiser G.), pp. 39–114 Oxford, UK: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price T. 2008. Speciation in birds. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jetz W, Thomas GH, Joy JB, Hartmann K, Mooers AO. 2012. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature 491, 444–448 (doi:10.1038/nature11631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatesy SM, Dial KP. 1996. Locomotor modules and the evolution of avian flight. Evolution 50, 331–340 (doi:10.2307/2410804) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter JP. 1998. Key innovations and the ecology of macroevolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 31–36 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01273-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wainwright PC. 2007. Functional versus morphological diversity in macroevolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38, 381–401 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095706) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatesy SM, Middleton KM. 1997. Bipedalism, flight, and the evolution of theropod locomotor diversity. J. Vert. Paleontol. 17, 308–329 (doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010977) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton KM, Gatesy SM. 2000. Theropod forelimb design and evolution. Zoo. J. Linn. Soc. 128, 149–187 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00160.x) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrano MT, Sidor CA. 1999. Theropod hindlimb disparity revisited: comments on Gatesy and Middleton (1997). J. Vert. Paleontol. 19, 602–605 (doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011172) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidlauskas B. 2008. Continuous and arrested morphological diversification in sister clades of characiform fishes: a phylomorphospace approach. Evolution 62, 3135–3156 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00519.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke JA, Middleton KM. 2008. Mosaicism, modules, and the origin of birds: results from a Bayesian approach to the study of morphological evolution using discrete character data. Syst. Biol. 57, 185–201 (doi:10.1080/10635150802022231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrano MT, Sampson SD. 2008. The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 6, 183–236 (doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanno LE, Gillette DD, Albright LB, Titus AL. 2009. A new North American therizinosauroid and the role of herbivory in ‘predatory’ dinosaur evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3505–3511 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choiniere JN, Xu X, Clark JM, Forster CA, Guo Y, Han F. 2010. A basal alvarezsauroid theropod from the early Late Jurassic of Xinjiang, China. Science 327, 571–574 (doi:10.1126/science.1182143) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrano MT, Benson RBJ, Sampson SD. 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 10, 211–300 (doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner AH, Makovicky PJ, Norell MA. 2012. A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 371, 1–206 (doi:10.1206/748.1) [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor JK, Zhou Z-H. 2013. A redescription of Chaoyangia beishanensis (Aves) and a comprehensive phylogeny of Mesozoic birds. J. Syst. Palaeontol. (doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.690455) [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team 2012. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; See http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrano MT. 1998. Locomotor evolution in the dinosauria: functional morphology, biomechanics, and modern analogs. PhD thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bapst DW. 2012. Paleotree: an R package for paleontological and phylogenetic analyses of evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 803–805 (doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00223.x) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felsenstein J. 1985. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Nat. 125, 1–15 (doi:10.1086/284325) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revell LJ. 2009. Size-correction and principal components for interspecific comparative studies. Evolution 63, 3258–3268 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00804.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revell LJ. 2012. Phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223 (doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harmon LJ, Weir J, Brock C, Glor R, Challenger W, Hunt G. 2009. Geiger: analysis of evolutionary diversification. R package v. 1.3-1 See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=geiger [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eastman JM, Alfaro ME, Joyce P, Hipp AL, Harmon LJ. 2011. A novel method for identifying shifts in the rate of character evolution on trees. Evolution 65, 3578–3589 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01401.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan KMA, Moore BR. 2005. SymmeTREE: whole-tree analysis of differential diversification rates. Bioinformatics 21, 855–865 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti175) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarver JE, Donoghue PCJ. 2011. The trouble with topology: phylogenies without fossils provide a revisionist perspective of evolutionary history in topological analyses of diversity. Syst. Biol. 60, 700–712 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt G. 2012. Measuring rates of phenotypic evolution and the inseparability of tempo and mode. Paleobiology 38, 351–373 (doi:10.1666/11047.1) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan C, Hone DWE, Xu X, Zhang F-C. 2010. The asymmetry of the carpal joint and the evolution of wing folding in maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 2027–2033 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2281) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barsbold R, Currie PJ, Myhrvold NP, Osmólska H, Tsogtbaatar K, Watabe M. 2000. A pygostyle from a non-avian theropod. Nature 403, 155–156 (doi:10.1038/35003103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, Cheng Y-N, Wang X-L, Chang C-H. 2003. Pygostyle-like structure from Beipiaosaurus (Theropoda, Therizinosauroidea) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning, China. Acta Geol. Sin. 77, 294–298 (doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2003.tb00744.x) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dececchi TA, Larsson HCE. 2009. Patristic evolutionary rates suggest a punctuated pattern in forelimb evolution before and after the origin of birds. Paleobiology 35, 1–12 (doi:10.1666/07079.1) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiappe LM. 1995. The first 85 millions years of avian evolution. Nature 378, 349–355 (doi:10.1038/378349a0) [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connor JK, Chiappe LM. 2011. A revision of enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithoraces) skull morphology. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 9, 135–157 (doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.526639) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erickson GM, Rauhut OWM, Zhou Z-H, Turner AH, Inouye BD, Hu D, Norell MA. 2009. Was dinosaurian physiology inherited by birds? Reconciling slow growth in Archaeopteryx. PLoS ONE 4, e7390 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007390) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lloyd GT, Davis KE, Pisani D, Tarver JE, Ruta M, Sakamoto M, Hone DW, Jennings R, Benton MJ. 2008. Dinosaurs and the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2483–2490 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0715) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Z-H, Wang Y. 2010. Vertebrate diversity of the Jehol Biota as compared with other Lagerstätten. Sci. China Earth Sci. 53, 1894–1907 (doi:10.1007/s11430-010-4094-9) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feduccia A. 1995. Explosive evolution in Tertiary birds and mammals. Science 267, 637–638 (doi:10.1126/science.267.5198.637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alroy J. 2010. The shifting balance of diversity among major marine animal groups. Science 329, 1191–1194 (doi:10.1126/science.1189910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabosky DL, Slater GJ, Alfaro ME. 2012. Clade age and species richness are decoupled across the eukaryotic tree of life. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001381 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quental TB, Marshall CR. 2010. Diversity dynamics: molecular phylogenies need the fossil record. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 434–441 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slater GJ, Harmon LJ, Alfaro ME. 2012. Integrating fossils with molecular phylogenies improves inference of trait evolution. Evolution 66, 3931–3944 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01723.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gingerich PD. 2001. Rates of evolution on the time scale of the evolutionary process. Genetica 112–113, 127–144 (doi:10.1023/A:1013311015886) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harmon LJ, et al. 2010. Early bursts of body size and shape evolution are rare in comparative data. Evolution 64, 2385–2396 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01025.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Longrich NR, Tokaryk T, Field DJ. 2011. Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15 253–15 257 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1110395108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]