Abstract

In this study, the effect of the substrate roughness on adhesion of mushroom-shaped microstructure was experimentally investigated. To do so, 12 substrates having different isotropic roughness were prepared from the same material by replicating topography of different surfaces. The pull-off forces generated by mushroom-shaped microstructure in contact with the tested substrates were measured and compared with the pull-off forces generated by a smooth reference. It was found that classical roughness parameters, such as average roughness (Ra) and others, cannot be used to explain topography-related variation in pull-off force. This has led us to the development of an integrated roughness parameter capable of explaining results of pull-off measurements. Using this parameter, we have also found that there is a critical roughness, above which neither smooth nor microstructured surface could generate any attachment force, which may have important implications on design of both adhesive and anti-adhesive surfaces.

Keywords: biomimetics, attachment, fibrillar adhesives, pull-off force, surface topography

1. Introduction

The problem of quick and easy reversible attachment is of great importance in different fields of technology. For this reason, inspired by high-performance attachment systems of some lizards, spiders and insects allowing them to adhere and run on inverted surfaces [1], a new field of adhesion science has emerged during the past decade. Several works [2–5] focused on understanding the physics behind the spectacular performance of these systems have confirmed that the structural and functional principles used by biological systems may be utilized to design artificial surfaces with enhanced adhesion capacity. In the light of this finding, many attempts have been made to amplify adhesion of a flat contact by modifying contact geometry, which opened a race for new bioinspired dry adhesives [6–10] (and many more, for recent review see reference [11]).

One of a few truly working dry biomimetic adhesives developed so far is the one based on mushroom-shaped contact elements [12]. Inspired by the adhesive hairs evolved in male beetles from the family Chrysomelidae, this type of attachment system performs well on smooth substrates, while being able to generate strong pull-off force nearly without any preload. The potential of this artificial attachment system has been verified in allowing a 120 g walking robot to climb smooth vertical surfaces [13] and, very recently, a 70 kg person to hang on a glass ceiling [14].

Much research has been carried out on studying various properties of mushroom-shaped adhesive microstructure and the effects of preload and contamination [12], shear [15], overload [16], tilt [17], hierarchy [18], ambient pressure [19], oil lubrication [20] and submerging underwater [21] were elucidated. Following experimental research, theoretical explanations of mushroom shape advantages were also provided [22,23]. However, the effect of counterface roughness on adhesion of biomimetic mushroom-shaped microstructure has not been systematically studied yet. It is obvious that the counterface roughness is a vital factor that may affect the design of microstructured adhesives [20]. For this reason, in this study, we investigate the effect of roughness and identify the key roughness parameters responsible for the observed variation in pull-off force.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Specimen

Mushroom-shaped microstructure (figure 1a) was manufactured [24] by Gottlieb binder GmbH (Holzgerlingen, Germany) at room temperature by pouring two-compound polymerizing poly(vinylsiloxane) (PVS; Coltène Whaledent AG, Altsätten, Switzerland) into the holed template lying on a smooth support. After polymerization, the ready-to-use cast tape of about 0.3 mm in width with Young's modulus of about 3 MPa [25] was removed from the template. Mushroom-shaped microstructure consisted of hexagonally packed pillars of about 100 µm in height bearing terminal contact plates of about 50 µm in diameter (figure 1a). The area density of the terminal contact plates was about 48%. The backside of the cast microstructured tape was used for smooth reference surface. To prepare the samples, the tape was placed on a glass support while facing either structured or smooth side up. Then, the same two-compound fast-polymerizing PVS was poured onto this tape from above. Prospective specimen height was defined by the spacers placed between the support and a covering flat surface that was used to squeeze superfluous polymer out of the gap. Using disposable biopsy Uni-Punch (Premier Products Co., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), samples of 2 mm in diameter were punched out of the resulting 1 mm height PVS casts having either structured or smooth contact surface and always smooth back surface. To fix the samples, we glued their smooth back surface to the specimen holders using the same PVS.

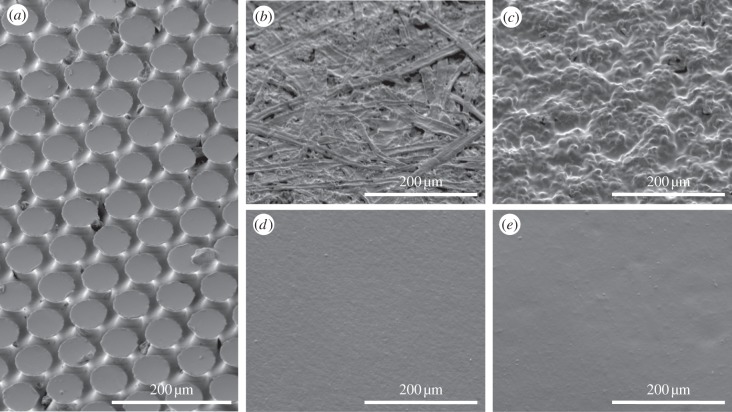

Figure 1.

Mushroom-shaped adhesive microstructure made of (a) PVS and Epoxy counterfaces (b) 6, (c) 4, (d) 1, (e) 5, with numbers according to table 1.

Counterface samples of 15 × 4 × 1 mm3 in size replicating 12 surfaces of different isotropic roughness (figure 1b–d and table 1) were cast out of 2 Ton Clear Weld Epoxy, (ITW Devcon, Riviera Beach, FL, USA) using a two-step moulding technique [26]. This helped studying the effect of surface topography only, while avoiding introduction of material-related differences in adhesion. The surfaces to be replicated were chosen from various office and laboratory objects, such as table, folder, different types of paper, microscope base and microscope slide, so to cover as large a range of roughness as possible.

Table 1.

Mean roughness parameters measured at three different sites on each Epoxy replica.

| replica | Ra (µm) | Rmax (µm) | Rpk (µm) | Sm (mm) | σs (µm) | β (µm) | η (µm−2) | original surface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.193 | 0.306 | 0.306 | 0.048 | 2.010 | 24.554 | 0.045 | abrasive paper |

| 2 | 0.953 | 1.070 | 1.070 | 0.054 | 4.718 | 11.253 | 0.005 | abrasive paper |

| 3 | 1.683 | 1.587 | 1.587 | 0.075 | 4.137 | 9.473 | 0.004 | abrasive paper |

| 4 | 2.287 | 2.253 | 2.253 | 0.075 | 5.390 | 7.651 | 0.003 | abrasive paper |

| 5 | 0.237 | 0.393 | 0.393 | 0.064 | 4.472 | 24.439 | 0.037 | microscope slide |

| 6 | 2.510 | 2.087 | 2.087 | 0.103 | 2.956 | 8.058 | 0.003 | office paper |

| 7 | 1.767 | 2.173 | 2.173 | 0.090 | 4.426 | 12.414 | 0.004 | hard paper |

| 8 | 1.010 | 0.520 | 0.520 | 0.160 | 8.712 | 19.859 | 0.007 | hard paper |

| 9 | 1.793 | 0.897 | 0.897 | 0.358 | 9.728 | 20.953 | 0.011 | microscope base |

| 10 | 4.363 | 2.807 | 2.807 | 0.339 | 10.327 | 15.212 | 0.008 | office table |

| 11 | 1.230 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.169 | 3.818 | 19.871 | 0.008 | hard paper |

| 12 | 2.270 | 1.383 | 1.383 | 0.440 | 7.619 | 20.977 | 0.013 | plastic folder |

2.2. Equipment

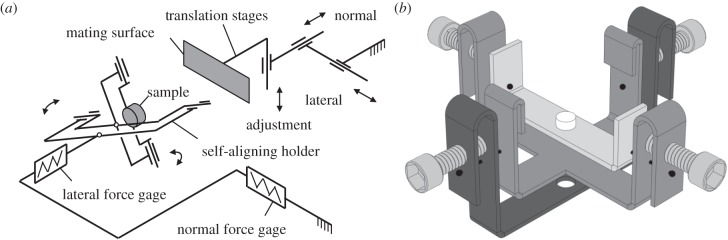

Surface appearance of the specimens used was imaged in an FEI Quanta 200 environmental scanning electron microscope (FEI Co., Brno, Czech Republic). Surface roughness was measured with a mechanical profiler Hommel LV-100 (Hommelwerke GmbH, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany). The tests were performed on a home-made tribometer [27] incorporating two main units used for driving and measuring purposes (figure 2a). The drive unit consists of three motorized translation stages used to load the contact by moving the mating surface. The measurement unit consists of two load cells used to determine the forces acting on the sample. To guarantee full contact and fulfil the ‘equal load sharing’ principle [28] during pull-off force measurements in a flat-on-flat contact scheme, essential in surface texture testing, a passive self-aligning system of specimen holders was used (figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic of the home-made tribometer used [27]. (b) Passive self-aligning sample holder based on two orthogonal axes of rotation coplanar with the contact plane [27]. The system is made much more user-friendly by using thread-tightening screws simplifying considerably preliminary adjustments.

2.3. Procedure

Each test started by bringing the Epoxy counterface in contact with the PVS sample. Taking into account that pull-off force generated in flat-on-flat contact is independent of the preload [12], only one normal load was applied in this study. After applying the normal load of 90 mN (nominal contact pressure of about 29 kPa), the pull-off force was measured while withdrawing the translation stage at a velocity of 100 µm s−1. Each tribo-pair was tested at least five times, each time on a different region of the counterface. Prior to experiments, the samples were washed with deionized water and liquid soap, and then dried in blowing nitrogen. The experiments were carried out at temperature and relative humidity of 20–22°C and 55–60%, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

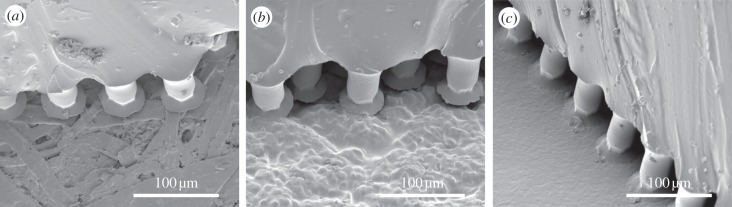

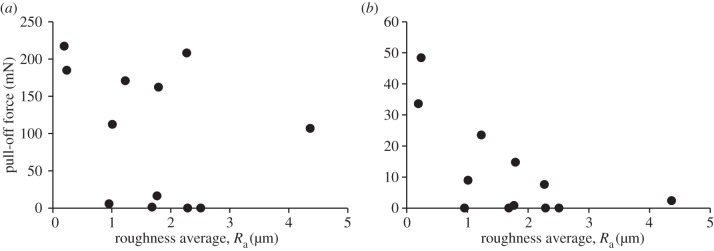

Average values of pull-off force measured between the PVS specimens and the Epoxy counterfaces are reported in table 2. Simple comparison of the obtained results shows that at certain types of roughness mushroom-shaped microstructure adheres more than 40 times stronger than smooth surface made of the same material, whereas, in other cases, both types of specimens generate the same negligible adhesion. Obviously, this results from the differences in topography of counterfaces leading to different contact conditions (figure 3). In order to better understand the relationship between surface texture and operation, we have analysed results of the measured pull-off force as a function of various roughness parameters. Figure 4 presents the pull-off force generated by mushroom-shaped microstructure and smooth surface as a function of the counterface Ra. It is clear that there is no correlation between the pull-off force and the Ra, as nearly the same force can be achieved on the surfaces characterized by the Ra values differing by approximately an order of magnitude, and vice versa. In addition to Ra, we have also tested the effect of other classical roughness parameters, such as maximum roughness depth Rmax, reduced peak height Rpk, mean spacing of profile irregularities Sm, etc. (table 1), and obtained the same lack of correlation between any single parameter and the measured pull-off force.

Table 2.

Mean values of pull-off force measured between the PVS specimens and the Epoxy counterfaces.

| replica | structured surface pull-off force, Ps (mN) | smooth surface pull-off force, Pf (mN) | Ps/Pf |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 217.3 | 33.6 | 6.47 |

| 2 | 5.7 | 0 | n.a. |

| 3 | 1.2 | 0 | n.a. |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | n.a. |

| 5 | 185.0 | 48.4 | 3.82 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | n.a. |

| 7 | 16.2 | 0.8 | 19.29 |

| 8 | 112.2 | 8.9 | 12.54 |

| 9 | 162.1 | 14.7 | 11.00 |

| 10 | 107.0 | 2.4 | 44.58 |

| 11 | 170.7 | 23.5 | 7.26 |

| 12 | 208.0 | 7.6 | 27.37 |

Figure 3.

Mushroom-shaped adhesive microstructure in contact with Epoxy counterfaces (a) 6, (b) 4 and (c) 1, with numbers according to table 1.

Figure 4.

(a) Pull-off force of mushroom-shaped PVS microstructure and (b) smooth PVS surface presented as a function of the Epoxy counterface roughness average Ra.

Taking into account the fact that the only difference between the adhesion of tested counterfaces comes from the variation in their roughness (all other parameters are kept constant), it is reasonable to assume that there is a certain roughness characteristic capable of correlating with the observed changes in pull-off force. Analysing the surface features that may affect adhesion, it is possible to come to the conclusion that the most important role is played by the surface asperities [29]. It is obvious that the more asperities (contact points) the surface bears, the larger the adhesion is. Similarly, asperities of larger radius generate larger adhesion [30,31]. On the other hand, adhesion decreases with increasing dispersion of asperity heights [29]. Based on these tendencies and using the surface density of asperities η, the mean radius of asperity summits β and the standard deviation of asperity height distribution σs [32], we defined a new adhesion-oriented integrative roughness parameter Ri:

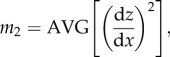

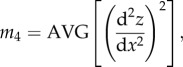

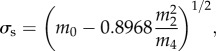

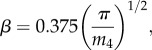

Parameters σs, β and η are not readily calculated by standard roughness analysis software, so we have obtained them using the following approach [33,34]. First, each digitized profilometric trace (we have measured three traces for each substrate) was analysed to determine spectral moments m0, m2, m4

|

|

where the AVG operator computes the arithmetic average, and z(x) is the surface height profile. Then, assuming isotropic roughness of a normally distributed height, the values of σs, β and η were obtained from the spectral moments of each digitized trace as

|

|

Finally, to compute the Ri for each substrate, the values of σs, β and η were averaged (table 1) for three corresponding traces.

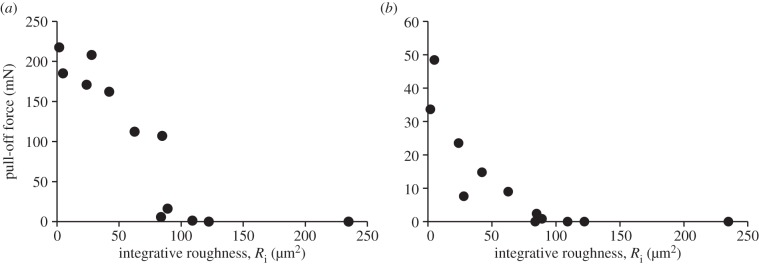

Figure 5 presents the pull-off force generated by mushroom-shaped microstructure and smooth surface as a function of a new roughness parameter Ri. This chart shows a clear correlation between the two in both microstructured and smooth samples. The effect of roughness, however, is different in two types of surfaces. In smooth surface, the pull-off force decreases with increasing roughness of counterface with approximately constant rate, whereas in microstructured surface, the pull-off force first decreases slowly, remaining on nearly the same level across a wide range of roughness, and then falls sharply at certain critical roughness. This means that mushroom-shaped microstructure is much more robust and tolerant to irregularities of the counterface, resulting in a more than 40-fold increase in pull-off force that may be achieved in comparison with smooth surface made of the same material.

Figure 5.

(a) Pull-off force of mushroom-shaped PVS microstructure and (b) smooth PVS surface presented as a function of the Epoxy counterface integrative roughness Ri.

Yet another interesting point is that, surprisingly, the critical roughness at which the pull-off force approaches zero is the same despite entirely different topography of both types of the tested elastomeric samples. This may possibly mean that each pair of materials has its own critical roughness characterizing the passage from an adhesive to a non-adhesive surface state. This concept may find wide use in designing surfaces of tailored adhesive properties. The question of whether this assumption is true, however, remains open and calls for further research.

4. Conclusion

The measurements performed demonstrate that attachment ability of mushroom-shaped microstructure is less sensitive to a variation in counterface roughness than smooth surface made of the same material. This robustness supplements a list of advantages that this texture has in possession and gives more weight to the reasons why many naturally evolved biological attachment systems are based on mushroom-shaped geometry [35].

Analysing the effects of roughness, we have shown that classical parameters cannot be used to explain topography-related variation in pull-off force. This has led us to the development of an Ri capable of presenting the pull-off force data in a readable way. Using this parameter, we have also found that there is a critical roughness, above which neither smooth nor microstructured surface can generate any adhesion. This newly developed parameter may have important implications on design of both adhesive and anti-adhesive surfaces.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stanislav Gorb for helpful discussion and Alexey Tsipenyuk for preparation of self-aligning unit.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Technion V.P.R. Fund and the B. and G. Greenberg Research Fund (Ottawa). H.K. was supported by The Center for Absorption in Science, Ministry of Immigrant Absorption, State of Israel.

References

- 1.Scherge M, Gorb SN. 2001. Biological micro- and nanotribology: nature's solutions. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persson BNJ. 2003. On the mechanism of adhesion in biological systems. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 7614–7621. ( 10.1063/1.1562192) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glassmaker NJ, Jagota A, Hui CY, Kim J. 2004. Design of biomimetic fibrillar interfaces. I. Making contact. J. R. Soc. Interface 1, 23–33. ( 10.1098/rsif.2004.0004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian Y, Pesika N, Zeng H, Rosenberg K, Zhao B, McGuiggan P, Autumn K, Israelachvili J. 2006. Adhesion and friction in gecko toe attachment and detachment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19 320–19 325. ( 10.1073/pnas.0608841103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varenberg M, Pugno N, Gorb S. 2010. Spatulate structures in biological fibrillar adhesion. Soft Matter 6, 3269–3272. ( 10.1039/c003207g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geim AK, Dubonos SV, Grigorieva IV, Novoselov KS, Zhukov AA, Shapoval SY. 2003. Microfabricated adhesive mimicking gecko foot-hair. Nat. Mater. 2, 461–463. ( 10.1038/nmat917) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim S, Sitti M. 2006. Biologically inspired polymer microfibers with spatulate tips as repeatable fibrillar adhesives. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 261911 ( 10.1063/1.2424442) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner C, del Campo A, Arzt E. 2007. Adhesion of bioinspired micropatterned surfaces: Effects of pillar radius, aspect ratio, and preload. Langmuir 23, 3495–3502. ( 10.1021/la0633987) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassmaker NJ, Jagota A, Hui CY, Noderer WL, Chaudhury MK. 2007. Biologically inspired crack trapping for enhanced adhesion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10 786–10 791. ( 10.1073/pnas.0703762104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parness A, Soto D, Esparza N, Gravish N, Wilkinson M, Autumn K, Cutkosky M. 2009. A microfabricated wedge-shaped adhesive array displaying gecko-like dynamic adhesion, directionality and long lifetime. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 1223–1232. ( 10.1098/rsif.2009.0048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagota A, Hui CY. 2011. Adhesion, friction, and compliance of bio-mimetic and bio-inspired structured interfaces. Mat. Sci. Eng. R 72, 253–292. ( 10.1016/j.mser.2011.08.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorb S, Varenberg M, Peressadko A, Tuma J. 2007. Biomimetic mushroom-shaped fibrillar adhesive micro-structure. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 271–275. ( 10.1098/rsif.2006.0164) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daltorio KA, Gorb S, Peressadko A, Horchler AD, Ritzmann RE, Quinn RD. 2005. A robot that climbs walls using micro-structured polymer feet. In Proc. Int. Conf. Climbing and Walking Robots, London, UK, pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heepe L, Kovalev AE, Varenberg M, Tuma J, Gorb SN. 2012. First mushroom-shaped adhesive microstructure: a review. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2, 014008 ( 10.1063/2.1201408) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varenberg M, Gorb SN. 2007. Shearing of fibrillar adhesive microstructure: friction and shear-related changes in pull-off force. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 721–725. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.0222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varenberg M, Gorb S. 2008. Close-up of mushroom-shaped fibrillar adhesive microstructure: contact element behavior. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 785–789. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.1201) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy MP, Aksak B, Sitti M. 2009. Gecko-inspired directional and controllable adhesion. Small 5, 170–175. ( 10.1002/smll.200801161) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy MP, Kim S, Sitti M. 2009. Enhanced adhesion by gecko-inspired hierarchical fibrillar adhesives. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 1, 849–855. ( 10.1021/am8002439) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heepe L, Varenberg M, Itovich Y, Gorb SN. 2011. Suction component in adhesion of mushroom-shaped microstructure. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 585–589. ( 10.1098/rsif.2010.0420) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovalev A, Varenberg M, Gorb S. 2012. Wet versus dry adhesion of biomimetic mushroom-shaped microstructure. Soft Matter 8, 3560–3566. ( 10.1039/c2sm25431j) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varenberg M, Gorb S. 2008. A beetle-inspired solution for underwater adhesion. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 383–385. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.1171) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spuskanyuk AV, McMeeking RM, Deshpande VS, Arzt E. 2008. The effect of shape on the adhesion of fibrillar surfaces. Acta Biomater. 4, 1669–1676. ( 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.05.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbone G, Pierro E, Gorb SN. 2011. Origin of the superior adhesive performance of mushroom-shaped microstructured surfaces. Soft Matter 7, 5545–5552. ( 10.1039/c0sm01482f) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuma J. 2007. Process for creating adhesion elements on a substrate material. US Patent 20070063375 A1.

- 25.Peressadko A, Gorb SN. 2004. When less is more: experimental evidence for tenacity enhancement by division of contact area. J. Adhes. 80, 247–261. ( 10.1080/00218460490430199) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorb SN. 2007. Visualization of native surfaces by two-step molding. Microsc. Today 15, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murarash B, Varenberg M. 2011. Tribometer for in situ scanning electron microscopy of microstructured contacts. Tribol. Lett. 41, 319–323. ( 10.1007/s11249-010-9717-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui CY, Glassmaker NJ, Tang T, Jagota A. 2004. Design of biomimetic fibrillar interfaces: 2. Mechanics of enhanced adhesion. J. R. Soc. Interface 1, 35–48. ( 10.1098/rsif.2004.0005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuller KNG, Tabor D. 1975. The effect of surface roughness on the adhesion of elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 345, 327–342. ( 10.1098/rspa.1975.0138) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson KL, Kendall K, Roberts AD. 1971. Surface energy and the contact of elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 324, 301–313. ( 10.1098/rspa.1971.0141) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derjaguin BV, Muller VM, Toporov YP. 1975. Effect of contact deformations on the adhesion of particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 53, 314–326. ( 10.1016/0021-9797(75)90018-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenwood JA, Williamson JBP. 1966. Contact of nominally flat surfaces. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 295, 300–319. ( 10.1098/rspa.1966.0242) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCool JI. 1987. Relating profile instrument measurements to the functional performance of rough surfaces. ASME J. Tribol. 109, 264–270. ( 10.1115/1.3261349) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pawar G, Pawlus P, Etsion I, Raeymaekers B. 2013. The effect of determining topography parameters on analyzing elastic contact between isotropic rough surfaces. ASME J. Tribol. 135, 011401 ( 10.1115/1.4007760) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorb SN, Varenberg M. 2007. Mushroom-shaped geometry of contact elements in biological adhesive systems. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 21, 1175–1183. ( 10.1163/156856107782328317) [DOI] [Google Scholar]