Abstract

Background

Radiation treatment results in a severe diminution of osseous vascularity. Intermittent parathyroid hormone (PTH) has been shown to have an anabolic effect on osteogenesis, though its impact on angiogenesis remains unknown. In this murine model of distraction osteogenesis, we hypothesize that radiation treatment will result in a diminution of vascularity in the distracted regenerate and that delivery of intermittent systemic PTH will promote angiogenesis and reverse radiation induced hypovascularity.

Materials and methods

Nineteen Lewis rats were divided into three groups. All groups underwent distraction of the left mandible. Two groups received radiation treatment to the left mandible prior to distraction, and one of these groups was treated with intermittent subcutaneous PTH (60 μg/kg, once daily) beginning on the first day of distraction for a total duration of 21 days. One group underwent mandibular distraction alone, without radiation. After consolidation, the rats were perfused and imaged with micro-CT angiography and quantitative vascular analysis was performed.

Results

Radiation treatment resulted in a severe diminution of osseous vascularity in the distracted regenerate. In irradiated mandibles undergoing distraction osteogenesis, treatment with intermittent PTH resulted in significant increases in vessel volume fraction, vessel thickness, vessel number, degree of anisotropy, and a significant decrease in vessel separation (p < 0.05). No significant difference in quantitative vascularity existed between the group that was irradiated, distracted and treated with PTH and the group that underwent distraction osteogenesis without radiation treatment.

Conclusions

We quantitatively demonstrate that radiation treatment results in a significant depletion of osseous vascularity, and that intermittent administration of PTH reverses radiation induced hypovascularity in the murine mandible undergoing distraction osteogenesis. While the precise mechanism of PTH-induced angiogenesis remains to be elucidated, this report adds a key component to the pleotropic effect of intermittent PTH on bone formation and further supports the potential use of PTH to enhance osseous regeneration in the irradiated mandible.

Keywords: Parathyroid hormone, angiogenesis, distraction osteogenesis, radiation, mandible

1. Introduction

Patients with oral cancer that undergo resection and reconstruction of the mandible often require adjuvant radiation treatment to control their disease. While effective at treating the cancer, the radiation treatment severely impairs osseous healing and degrades existing bone. Radiation directly injures osteocytes, resulting in both immediate and delayed cellular death and a rise in empty lacunae [1-3]. Bone density is significantly decreased after radiation treatment [1]. Radiation treatment delivered to bone also induces progressive endarteritis, diminishing vascularity on a macroscopic and microscopic level [1, 4, 5]. Radiation induced depletion of vascularity is dose-dependent and the changes have been thought to be irreversible [1, 3, 4, 6]. In a landmark article, Marx [2] described the “three H” principle, stating that irradiated tissue is hypoxic, hypocellular, and hypovascular compared to nonirradiated tissue. While radiation treatment impairs many factors required for successful bone healing, the impairment of vascularity is believed to play a key role in the majority of radiation-related osseous complications [1]. Adjunctive agents that can potentially restore vascularity to radiated bone and/or mitigate radiation induced vascular depletion could have a profound effect on assuaging radiation related injury.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) has the potential for anabolic and catabolic effects on bone metabolism, depending on the dosage regimen. Intermittent dosing of PTH results in a net increase in bone mass while continuous infusion of PTH results in a net loss of bone mass [7] as the anabolic and catabolic effects of PTH are determined primarily by the duration of time that serum concentrations of PTH remain elevated [8]. The anabolic effect of intermittent PTH on bone formation is largely attributed to an increase in the number of matrix-synthesizing osteoblasts [9-15]. Intermittent PTH has been shown to have a pleiotropic effect, increasing osteoblast number by promoting osteoblastogenesis, inhibiting osteoblast apoptosis, and reactivating lining cells to resume matrix synthesizing function [16, 17].

In animal fracture models, intermittent PTH improves and accelerates union [18, 19] and increases callus formation and mechanical strength [20]. The osteogenic potential of PTH is also demonstrated by its ability to enhance the healing of bone grafts [21]. Teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] is currently FDA-approved for the treatment of osteoporosis, and has shown the ability to increase bone density in postmenopausal women [22]. In patients undergoing posterolateral lumbar fusion with local bone grafts, treatment with PTH significantly improved the rate and duration of bone union [23]. PTH also accelerates fracture healing in patients with pelvic [24] and distal radius fractures [25]. Case reports suggest that PTH treatment may have a role in ameliorating bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw [26, 27].

Previous work in our laboratory has shown that PTH has the ability to reverse the deleterious effects of radiation on osseous regeneration in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis (DO) [28]. DO is a form of endogenous tissue engineering whereby new bone formation is stimulated by the gradual separation of two osteogenic fronts [29]. The intense osteogenic and angiogenic response that occurs in close temporal and spatial proximity also makes DO a valuable experimental model to analyze the potential effects of therapeutic agents on osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Gallagher et al. [28] observed that treatment with intermittent PTH enhanced bone regeneration in irradiated bone undergoing DO, demonstrated by significant improvements in bone volume fraction, bone mineral density, and union quality.

The capability of PTH to enhance an irradiated bone's ability to form a substantial and bountiful regenerate is promising. However, the effect of PTH on angiogenesis in irradiated bone has yet to be elucidated. More work is needed to determine the mechanism by which it can function to mitigate the deleterious effects of radiation induced injury. In this murine model of DO, we hypothesize that radiation treatment results in a diminution of vascularity in the distracted regenerate and that delivery of intermittent systemic PTH will promote angiogenesis and thereby reverse radiation induced hypovascularity. To our knowledge, a key link between the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH administration and angiogenesis has yet to be established.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental Groups

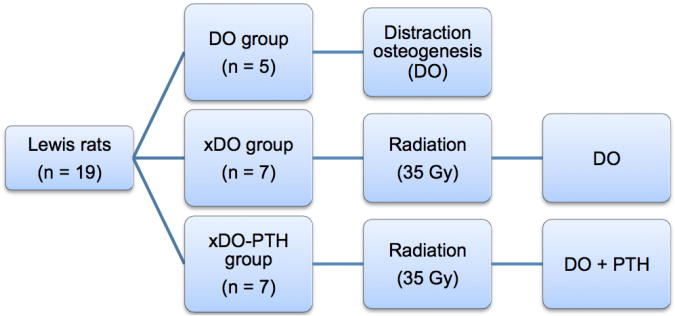

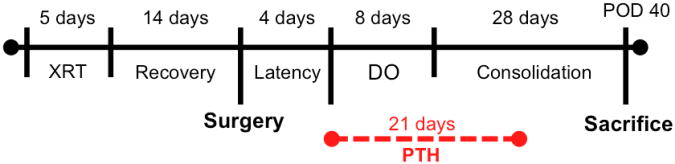

Nineteen twelve-week-old isogenic male Lewis rats were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups: DO, xDO, and xDO-PTH (Figure 1). All groups underwent surgical placement of mandibular distractors and underwent mandibular distraction osteogenesis. The DO (n=5) group was the normal control group and underwent mandibular distraction osteogenesis. The DO group did not receive radiation treatment. The xDO (n=7) group was the radiation control group and received preoperative radiation treatment followed by mandibular distraction osteogenesis. The xDO-PTH (n=7) group received preoperative radiation treatment followed by mandibular distraction osteogenesis and intermittent subcutaneous PTH (60 μg/kg, once daily) beginning on the first day of distraction for a total duration of 21 days. Our animal protocol has been reviewed and approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. The experimental timeline is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Experimental groups. The DO group was the normal control group and underwent mandibular distraction alone without radiation treatment. The xDO group underwent radiation treatment followed by mandibular distraction. The xDO-PTH group underwent radiation treatment, mandibular distraction, and intermittent PTH treatment (60 μg/kg/day) for 21 days. DO, distraction osteogenesis; Gy, gray; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Figure 2.

Experimental timeline. In the xDO-PTH group, parathyroid hormone (PTH) treatment was administered in one subcutaneous injection daily (60 μg/kg/day) for 21 days, beginning on the first day of mandibular distraction. XRT, radiation treatment; DO, distraction osteogenesis; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

2.2 Radiation Treatment

Rats were acclimated for 7 days in light and temperature controlled facilities and given hard chow and water without restriction. Radiation was delivered to the xDO and xDO-PTH groups; the DO group did not receive radiation. Prior to radiation, rats were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane. Induction was begun at 4%, after which anesthesia was maintained at 1.5%.

All radiation treatments were performed in the Irradiation Core at the University of Michigan Cancer Center using a Philips R250 orthovoltage unit (250kV, 15 mA; Kimtron Medical, Woodbury, CT). Radiation was delivered to the left hemimandible, 2-mm posterior to the third molar. Lead shielding was used to ensure localized delivery and to protect surrounding tissue. 7 Gy was delivered daily for 5 days for a total fractionated treatment dose of 35 Gy, which is the bioequivalent dose of 70 Gy in humans [30]. Dosimetry was carried out using an ionization chamber connected to an electrometer system, which was directly traceable to a National Institute of Standards and Technology calibration.

After completion of radiation, the xDO-PTH and xDO groups were allowed to recover for 14 days. During this period, all three groups were acclimated to a soft chow high-calorie diet (Hills-Columbus Serum; Columbus, Ohio). The percent of ration of calcium and phosphorus were 0.95% and 1.05% respectively, and the content of vitamin D was 4.5 IU per gram.

2.3 Surgery and postoperative care

All three groups underwent surgical placement of a mandibular distraction device with unilateral left mandibular osteotomy. The surgery was performed 14 days after completion of radiation in the xDO-PTH and xDO groups. Anesthesia was achieved with inhalational isoflurane (4% induction, 1.5% maintenance) and subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.3 mg/kg). A single dose of subcutaneous gentamicin (5 mg/kg) was given preoperatively.

The details of the surgical procedure have been previously described [31]; however, briefly, a 3-cm midline incision was placed ventrally from the anterior submentum. Skin flaps were elevated, exposing the anterolateral mandible. A stainless steel threaded pin was inserted transversely across the anterior mandible through a predrilled hole. Posteriorly, the masseter was incised along the inferior border of the mandible bilaterally, 2.5 mm anterior to the angle. Stainless steel threaded pins were then inserted through predrilled holes in the posterior mandible, approximately 4 mm anterior to the angle and 2 mm superior to the inferior border of the mandible. The pin ends were brought externally through the skin and the right mandible was rigidly fixed. The left mandible was fixed with a distraction screw for postoperative manipulation. A vertical osteotomy was made 2 mm posterior to the left third molar using a 10-mm microreciprocating blade (Stryker, Portage, MI). The osteotomy edges were carefully reapproximated in preparation for mandibular distraction. Because the surgical osteotomy is placed 2 mm posterior to the left third molar in each subject, this location represents the anterior margin of the osteotomy gap at the completion of distraction osteogenesis.

Postoperatively, rats were given two doses of subcutaneous gentamicin (5 mg/kg) every 12 hours to prevent infection. Subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg) was given every twelve hours through postoperative day (POD) 5. Staples were removed at POD 10. Weights were measured daily and subcutaneous lactated ringer solution was delivered as needed. Pin care was provided with Silvadene (Monarch Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Bristol, TN). Maxillary incisors were clipped weekly because of overgrowth from crossbite.

2.4 Mandibular distraction osteogenesis and region of interest

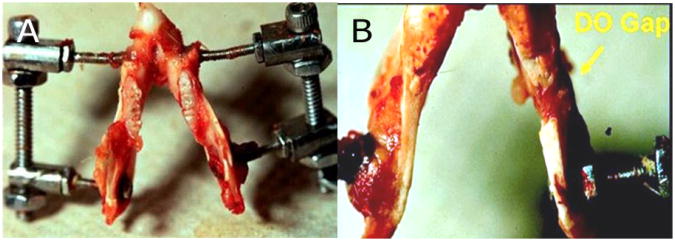

A photograph of the distraction device in a harvested mandible is shown in Figure 3. All rats began left mandibular distraction osteogenesis on POD 4. Distraction was performed at a rate of 0.3 mm every 12 hours to a total distraction gap of 5.1 mm. The 5.1 mm distraction gap was chosen because it was previously shown that the murine mandible can be reliably distracted to this distance with complete bony union [31]. The final distraction was completed on POD 12. Subjects then underwent a 28-day consolidation period prior to sacrifice and vascular analysis.

Figure 3.

(A) Superior view of murine mandible with distraction device after completion of distraction osteogenesis of the left hemimandible. (B) Inferior view of the same specimen, showing the 5.1 mm osteotomy gap in the left hemimandible (arrow). This osteotomy gap represented the region of interest for quantitative vascular analysis.

Bone formed within the 5.1 mm distraction gap was isolated and selected as our region of interest (ROI) for quantitative vascular analysis. The anterior margin of the ROI was 2 mm posterior to the left third molar, the site of the surgical osteotomy, and extended 5.1 mm in an anterior-posterior direction. The ROI is highlighted in Figure 4. Quantitative vascular metrics that account for the volume of bone within the ROI were employed in this study, because the volume of the osseous regenerate within the ROI in each subject was influenced by the individual subject's surrounding functional matrix.

Figure 4.

The surgical osteotomy is made 2 mm posterior to the third molar and the two segments of bone are distracted 0.3 mm every twelve hours to a total distraction gap of 5.1 mm. The 5.1 mm segment of regenerate bone represents the region of interest (shown in white) for quantitative vascular analysis.

2.5 Parathyroid hormone

Intermittent recombinant human PTH (1-34) (Bachem, CA) was administered to the xDO-PTH group in the postoperative period, beginning on the first day of distraction (POD 4). PTH (60 μg/kg) was delivered in intermittent fashion, once daily, and was injected subcutaneously over the right hindlimb. Treatment duration was 3 weeks; a total of 21 doses were delivered and treatment was completed on POD 25. The PTH treatment dose and duration employed in this study has previously been shown to improve union quality, bone mineral density, and bone volume fraction in a similar murine model of DO [28].

2.6 Perfusion and quantitative vascular analysis

After completion of the 28-day consolidation period, animals were sacrificed and vascular perfusion was performed. Animals were anesthetized with inhalational isoflurane (4%). Thoracotomy and left ventricular catheterization was performed. Following vessel fixation with heparinized normal saline and buffered formalin solution, the vasculature was injected with Microfil MV122 (Flow Tech; Carver, MA). Micro-CT after vessel perfusion with Microfil has been shown to be a robust and reproducible methodology for evaluation of craniofacial vascularity, and details of this procedure have been previously described [32]. Mandibles were harvested and demineralized in Cal-Ex II solution (Fisher Scientifics; Fairlawn, NJ). Leeching of mineral was confirmed with serial radiographs to ensure adequate demineralization prior to obtaining micro-computed tomography (CT) angiography, so that only vessels perfused with Microfil appeared on the scan.

Micro-CT images were analyzed using a three-dimensional image viewer, MicroView ABA 2.2 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Angiogenesis was quantified by stereological analysis of micro-CT images after reconstruction and orientation in a 3-dimensional x, y, and z plane. The 5.1-mm distracted segment in the left hemimandible was selected as the ROI and the scans were cropped and splined for quantitative analysis. In coronal view of the micro-CT, the left third molar served as the landmark for the ROI, as the anterior margin of the ROI was 2 mm posterior to the left third molar. The ROI extended 5.1 mm posterior to this location. The surgical osteotomy resulted in straight edges of bone that were visualized in sagittal view of the micro-CT, and this allowed secondary confirmation of the ROI margins.

MicroView uses algorithms to assign relative densities to the voxels based on the contrast content within the vessels. Analysis of vascularity in the ROI was accomplished by setting a global grayscale threshold of 1000 Hounsfield units to differentiate vessels from surrounding tissue. This threshold has been shown to be the optimal threshold for analysis to capture the maximal vascular content of the murine mandible after perfusion with Microfil [32].

MicroView reported five metrics, all of which control for the size of the ROI: vessel volume fraction, vessel number, vessel thickness, vessel separation, and degree of anisotropy. Because the individual subject's surrounding functional matrix influences the volume of bone within the ROI, the quantitative vascular metrics applied in this study account for the volume of bone within the ROI. Vessel volume fraction (VVF) depicts the fraction of bone occupied by the volume of vessels within the ROI tissue. Vessel number (VN) represents the mean number of vessels encountered by stochastic 1 mm lines in the ROI. Vessel thickness (VT) represents the intraluminal diameter of the vessel and is reported in μm. Vessel separation (VS) is the mean distance between the midaxes of two vessels within the ROI and is reported in mm. Degree of anisotropy (DA) measures the relative degree to which the vasculature has a directional dependence in the ROI and is determined using the mean intercept length method.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics software V. 20 (IBM; Armonk, NY). The data were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post-hoc analysis was performed by either Tukey or Games-Howell method, depending on the homogeneity of variances. Significance was assigned as p < 0.05.

3. Results

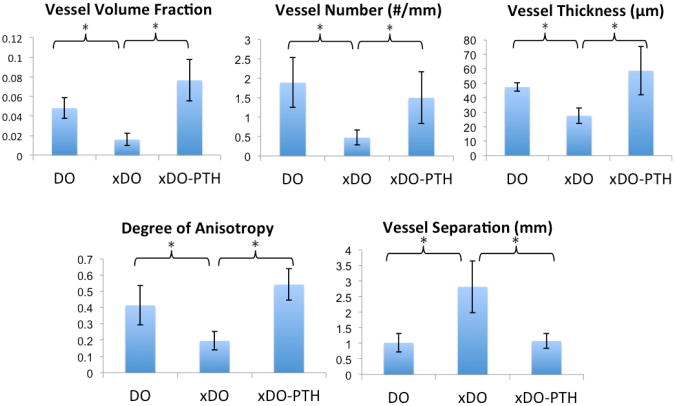

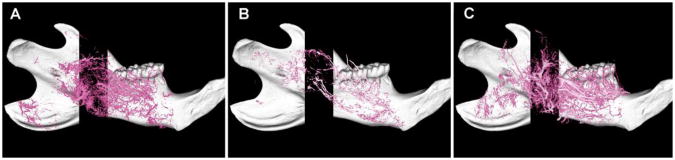

In all vascular metrics, a significant difference was found between treatment groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Representative maximal intensity projections are shown in Figure 5. As expected, the radiation treatment in the xDO group (radiation + distraction) resulted in a significant depletion of vascularity compared to the DO group (distraction alone) (Figures 5 and 6). Specifically, compared to the DO group, the xDO group showed a 3-fold decrease in vessel volume fraction (0.0159 v 0.0480; p = 0.004), 4-fold decrease in vessel number (0.472 v 1.89; p = 0.022), 1.7-fold decrease in vessel thickness (27.6 v 47.4; p = 0.023), and a 2.1-fold decrease in degree of anisotropy (0.196 v 0.414; p = 0.004). Vessel separation was increased 2.8-fold in the xDO group (2.82 v 1.02; p = 0.003) compared to the DO group.

Figure 5.

Representative lateral view maximal intensity projections of the perfused left mandibles in (A) DO, (B) xDO, and (C) xDO-PTH groups. The xDO-PTH and DO groups showed significant improvement in all vascular metrics compared to the xDO group. No significant difference in vascularity was found between the xDO-PTH and DO groups. Left = posterior, right = anterior.

Figure 6.

Quantitative vascular analysis. The xDO-PTH and DO groups showed significant improvement in all vascular metrics compared to the xDO group (* p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between the xDO-PTH and the DO groups.

Treatment with intermittent PTH significantly increased vascularity and reversed radiation induced hypovascularity in the xDO-PTH group (Figures 5 and 6). Specifically, compared to the xDO group (radiation + distraction), the xDO-PTH group (radiation + distraction + PTH) demonstrated a 4.8-fold increase in vessel volume fraction (0.0764 v 0.0159; p = 0.001), 3.2-fold increase in vessel number (1.50 v 0.472; p = 0.023), 2.1-fold increase in vessel thickness (58.7 v 27.6; p < 0.001), and 2.8-fold increase in degree of anisotropy (0.542 v 0.196; p < 0.001). Vessel separation was 2.6-fold greater in the xDO group compared to the xDO-PTH group (2.82 v 1.08; p = 0.005).

There were no measurable differences in vascularity between irradiated bone treated with PTH (xDO-PTH) and non-radiated bone (DO) (Figure 6). Specifically, comparing the xDO-PTH group (radiation + distraction + PTH) to the DO group (distraction alone), there was no significant difference in vessel volume fraction (0.0764 v 0.0480; p = 0.052), vessel number (1.50 v 1.89; p = 0.739), vessel thickness (58.7 v 47.4; p = 0.3), vessel separation (1.08 v 1.02; p = 0.986), or degree of anisotropy (0.542 v 0.414; p = 0.128).

4. Discussion

The most significant finding of this study is that PTH significantly reversed radiation induced hypovascularity in a murine model of irradiated distraction osteogenesis. In fact, PTH was able to restore osseous regenerate vascularity in irradiated bone to baseline levels, as there was no significant difference in vascularity between the irradiated group that received PTH (xDO-PTH group) and the group that underwent distraction alone (DO group) without radiation treatment. The xDO-PTH group demonstrated a trend toward increased vessel volume fraction compared to the DO group, though this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.052). To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate the ability of PTH to promote angiogenesis and reverse radiation induced hypovascularity in bone.

The primary outcome measure of this study was quantitative vascularity. Employing a similar irradiated murine model of distraction osteogenesis, we have previously shown that irradiated rats receiving PTH demonstrated improved union quality and a significant increase in bone volume fraction and bone mineral density compared to irradiated rats that were not treated with PTH [28]. The results of the current report and our previous study [28] suggest that intermittent PTH not only increases vascularity in irradiated bone but also improves the quality of the osseous regenerate. The mechanism of the anabolic behavior of intermittent PTH administration appears to involve the induction of both osteogenesis and angiogenesis in irradiated bone during DO.

More studies are needed to determine the precise mechanism by which intermittent PTH impacts angiogenesis. The current literature suggests that one potential pathway of PTH induced angiogenesis is via the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIFα)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway. Previous work has shown that osteogenesis and angiogenesis are tightly coupled via the HIFα/VEGF pathway [33]. HIFα is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that regulates cellular adaptation to hypoxia that is stabilized in osteoblasts in hypoxic conditions, mediating increased VEGF mRNA and protein expression [34-36]. Employing a mouse model of tibia DO, mice with constitutive HIFα activation in osteoblasts had markedly increased vascularity and bone formation in the distracted regenerate compared to mice lacking HIFα [37]. The increased vascularity and bone regeneration in mice with constitutive HIFα activation was VEGF-dependent, as administration of VEGF receptor antibodies impaired both angiogenesis and osteogenesis. Jacobsen et al. [38] employed mouse model of tibia DO and administered antibody blockade against VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 and reported an additive inhibitory effect on angiogenesis and bone formation within the osteotomy gap. Kleinheinz et al. [39] showed that delivery of rhVEGF165 resulted in significantly greater vascularity and bone density of bicortical mandibular defects in rabbits. In an irradiated model of mandibular DO, Farberg et al. [40] studied the effect of deferoxamine on union and vascularity. Deferoxamine is an iron chelator that prevents HIFα degradation and promotes VEGF production [40]. In their study, treatment with deferoxamine significantly promoted angiogenesis and also improved bony bridging of the distraction gap [40]. While comprehensive knowledge of the bone-vascular axis is still lacking, current knowledge supports the notion that osteogenesis and angiogenesis are coupled in a VEGF-dependent manner [41, 42].

The osteogenic effect of PTH is also dependent on VEGF-related mechanisms [43]. While PTH has been shown to stimulate the endothelial expression of VEGF in vitro [44], PTH also enhances VEGF A mRNA expression in bone [43]. Prisby et al. [43] employed Wistar rats and administered daily subcutaneous PTH at a dose of 100 μg/kg per day for 4 weeks, resulting in a significant increase in tibia VEGF A mRNA expression in the PTH-treated animals compared to control animals. Bone volume/tissue volume was significantly enhanced in animals treated with intermittent PTH for 30 days. The anabolic response to PTH was dependent upon VEGF signaling as the improvement in trabecular bone mass was negated by the administration of anti-VEGF antibody.

Prisby et al. [43] found that intermittent PTH did not increase vascular density. However, in PTH-treated animals, capillaries were relocated closer to osteoid seams, and the authors concluded that PTH spatially directs blood vessels closer to sites of new bone formation without increasing overall vascular density. Major differences in study design, however, do exist between our study and the study by Prisby et al. [43]. First, our model focused on the ability of PTH to ameliorate the hypovascularity induced by radiation treatment whereas Prisby et al. [43] studied non-radiated bone. Second, our model analyzed vascularity within a region of interest that was limited to the regenerate bone in a model of mandibular DO, representing a localized region of active bone formation. Third, our model analyzed craniofacial bone while Prisby et al. [43] studied appendicular bone. Previous studies investigating bone graft biology have shown that critical differences exist between endomembranous and endochondral bone in the context of osseous vascularization. Cancellous bone grafts undergo rapid and complete revascularization, while cortical bone grafts undergo slow and incomplete revascularization [45-48]. Because the relative proportion of cancellous to cortical bone is greater in endochondral bone than in endomembranous bone, osseous angiogenesis is influenced by its embryologic origin. Finally, differences also existed in rat species and PTH dosing (60 μg/kg vs 100 μg/kg).

This report adds to the mounting evidence in support of the ability of intermittent PTH to improve osseous regeneration in irradiated bone. The largest hurdle to clinical translation and use in irradiated patients is the “black box” warning for teriparatide [(rhPTH(1-34)], which exists because of the unexpected observation of osteosarcoma in rats chronically treated with PTH [49]. It is important to note that the rats in the Vahle et al. [49] study were treated with doses ranging 5 – 75 μg/kg, which is higher than the human therapeutic human dose of either 20 or 40 μg [22, 49]. Furthermore, rats were treated daily for up to 2 years, which represents 80-90% of their normal life span, complicating comparisons to clinical trials that employ short-term use of PTH. A follow-up study by Vahle et al. [50] showed that an unequivocal increase in osteosarcoma was only observed in rats after extended duration of treatment (20 or 24 months). Thus, the occurrence of osteosarcoma in rats appears to be dependent on treatment dose and duration. Species differences may also play a role in PTH-related osteosarcoma, as Vahle et al. [51] reported zero cases of osteosarcoma in cynomolgus monkeys treated daily with PTH (5 μg/kg) for 18 months, which represents 4.5-6 years in humans [52].

The incidence of osteosarcoma in humans treated with teriparatide remains unknown. In 2007, among > 300,000 patients worldwide that have been treated with teriparatide, Harper et al. [53] report one case of osteosarcoma in a patient treated with teriparatide for osteoporosis. Causality between teriparatide and osteosarcoma in humans has yet to be established as incidence is rare, consistent with background incidence of osteosarcoma [53, 54]. Additional research and surveillance are needed to further identify the therapeutic window and clinical scenarios in which teriparatide can be safely used. This report adds to the mounting evidence in support of the tremendous therapeutic potential PTH possesses in the enhancement of osseous regeneration in irradiated bone.

5. Conclusion

In a murine model of distraction osteogenesis, intermittent administration of PTH promoted angiogenesis and reversed radiation induced hypovascularity. In irradiated mandibles undergoing DO, treatment with intermittent PTH resulted in significant increases in vessel volume fraction, vessel thickness, vessel number, degree of vascular anisotropy, and a significant decrease in vessel separation (p < 0.05). No significant differences in vascularity existed between the group that was irradiated, distracted and treated with PTH and the group that simply underwent DO without radiation treatment. While the precise mechanism of PTH induced angiogenesis remains to be elucidated, this report adds a key component to the pleotropic effect of intermittent PTH on bone formation and further supports the potential use of PTH to enhance osseous regeneration in the irradiated mandible.

Highlights.

Radiation (XRT) depletes osseous vascularity during distraction osteogenesis (DO)

Intermittent parathyroid hormone (PTH) was delivered to irradiated bone undergoing DO

PTH promoted angiogenesis and significantly improved vascularity in irradiated bone

PTH reversed radiation induced hypovascularity

PTH treatment after XRT restored osseous regenerate vascularity to normal levels

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by both a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH-R01 CA 125187-01) to Dr. Steven R. Buchman and by a research grant “Effect of Anabolic PTH on Distracted Mandibular Bone” from the AAO-HNS.

Abbreviations

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- DO

distraction osteogenesis

- XRT

radiation treatment

- Gy

gray

- POD

postoperative day

- CT

computed tomography

- ROI

region of interest

- VVF

vessel volume fraction

- VN

vessel number

- VT

vessel thickness

- DA

degree of anisotropy

- VS

vessel separation

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HIFα

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephen Y. Kang, Email: steveyk@med.umich.edu.

Sagar S. Deshpande, Email: sdeshpa@med.umich.edu.

Alexis Donneys, Email: alexisd@med.umich.edu.

Joey J. Rodriguez, Email: jrodlane@gmail.com.

Noah S. Nelson, Email: noahnels@med.umich.edu.

Peter A. Felice, Email: pafelice@gmail.com.

Douglas B. Chepeha, Email: dchepeha@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Sanger JR, Matloub HS, Yousif NJ, Larson DL. Management of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:517–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx RE. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costantino PD, Friedman CD, Steinberg MJ. Irradiated bone and its management. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28:1021–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutright DE, Brady JM. Long-term effects of radiation on the vascularity of rat bone--quantitative measurements with a new technique. Radiat Res. 1971;48:402–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie XT, Qiu WL, Yuan WH, Wang ZH. Experimental study of radiation effect on the mandibular microvasculature of the guinea pig. Chin J Dent Res. 1998;1:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teknos TN, Myers LL. Surgical reconstruction after chemotherapy or radiation. Problems and solutions Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:679–87. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunness M, Hock JM. Anabolic effect of parathyroid hormone on cancellous and cortical bone histology. Bone. 1993;14:277–81. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frolik CA, Black EC, Cain RL, Satterwhite JH, Brown-Augsburger PL, Sato M, Hock JM. Anabolic and catabolic bone effects of human parathyroid hormone (1-34) are predicted by duration of hormone exposure. Bone. 2003;33:372–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindsay R, Cosman F, Zhou H, Bostrom MP, Shen VW, Cruz JD, Nieves JW, Dempster DW. A novel tetracycline labeling schedule for longitudinal evaluation of the short-term effects of anabolic therapy with a single iliac crest bone biopsy: early actions of teriparatide. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:366–73. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma YL, Zeng Q, Donley DW, Ste-Marie LG, Gallagher JC, Dalsky GP, Marcus R, Eriksen EF. Teriparatide increases bone formation in modeling and remodeling osteons and enhances IGF-II immunoreactivity in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:855–64. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lida-Klein A, Zhou H, Lu SS, Levine LR, Ducayen-Knowles M, Dempster DW, Nieves J, Lindsay R. Anabolic action of parathyroid hormone is skeletal site specific at the tissue and cellular levels in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:808–16. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobnig H, Turner RT. The effects of programmed administration of human parathyroid hormone fragment (1-34) on bone histomorphometry and serum chemistry in rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4607–12. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellido T, Ali AA, Plotkin LI, Fu Q, Gubrij I, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, O'Brien CA, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Proteasomal degradation of Runx2 shortens parathyroid hormone-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in osteoblasts. A putative explanation for why intermittent administration is needed for bone anabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50259–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jilka RL, O'Brien CA, Ali AA, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC. Intermittent PTH stimulates periosteal bone formation by actions on post-mitotic preosteoblasts. Bone. 2009;44:275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Bellido T, Roberson P, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:439–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40:1434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leaffer D, Sweeney M, Kellerman LA, Avnur Z, Krstenansky JL, Vickery BH, Caulfield JP. Modulation of osteogenic cell ultrastructure by RS-23581, an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)-related peptide-(1-34), and bovine PTH-(1-34) Endocrinology. 1995;136:3624–31. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozaka K, Miyakoshi N, Kasukawa Y, Maekawa S, Noguchi H, Shimada Y. Intermittent administration of human parathyroid hormone enhances bone formation and union at the site of cancellous bone osteotomy in normal and ovariectomized rats. Bone. 2008;42:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsubara S, Mori S, Mashiba T, Nonaka K, Seki A, Akiyama T, Miyamoto K, Cao Y, Manabe T, Norimatsu H. Human parathyroid hormone (1-34) accelerates the fracture healing process of woven to lamellar bone replacement and new cortical shell formation in rat femora. Bone. 2005;36:678–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreassen TT, Ejersted C, Oxlund H. Intermittent parathyroid hormone (1-34) treatment increases callus formation and mechanical strength of healing rat fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:960–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.6.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe Y, Takahata M, Ito M, Irie K, Abumi K, Minami A. Enhancement of graft bone healing by intermittent administration of human parathyroid hormone (1-34) in a rat spinal arthrodesis model. Bone. 2007;41:775–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohtori S, Inoue G, Orita S, Yamauchi K, Eguchi Y, Ochiai N, Kishida S, Kuniyoshi K, Aoki Y, Nakamura J, Ishikawa T, Miyagi M, Kamoda H, Suzuki M, Kubota G, Sakuma Y, Oikawa Y, Inage K, Sainoh T, Takaso M, Ozawa T, Takahashi K, Toyone T. Teriparatide accelerates lumbar posterolateral fusion in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E1464–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31826ca2a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peichl P, Holzer LA, Maier R, Holzer G. Parathyroid hormone 1-84 accelerates fracture-healing in pubic bones of elderly osteoporotic women. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1583–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aspenberg P, Johansson T. Teriparatide improves early callus formation in distal radial fractures. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:234–6. doi: 10.3109/17453671003761946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harper RP, Fung E. Resolution of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the mandible: possible application for intermittent low-dose parathyroid hormone [rhPTH(1-34)] J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:573–80. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau AN, Adachi JD. Resolution of osteonecrosis of the jaw after teriparatide [recombinant human PTH-(1-34)] therapy. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1835–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher KK, Deshpande S, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Sarhaddi D, Nelson NS, Chepeha DB, Buchman SR. Role of parathyroid hormone therapy in reversing radiation-induced nonunion and normalization of radiomorphometrics in a murine mandibular model of distraction osteogenesis. Head Neck. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hed.23216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe NM, Mehrara BJ, Dudziak ME, Steinbreck DS, Mackool RJ, Gittes GK, McCarthy JG, Longaker MT. Rat mandibular distraction osteogenesis: Part I. Histologic and radiographic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2022–32. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199811000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Monson LA, Farberg AS, Donneys A, Zehtabzadeh AJ, Razdolsky ER, Buchman SR. Dose-response effect of human equivalent radiation in the murine mandible: part I. A histomorphometric assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:114–21. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821741d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchman SR, Ignelzi MA, Jr, Radu C, Wilensky J, Rosenthal AH, Tong L, Rhee ST, Goldstein SA. Unique rodent model of distraction osteogenesis of the mandible. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:511–9. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jing XL, Farberg AS, Monson LA, Donneys A, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Buchman SR. Radiomorphometric Quantitative Analysis of Vasculature Utilizing Micro-Computed Tomography and Vessel Perfusion in the Murine Mandible. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstruction. 2012:223–230. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Wan C, Deng L, Liu X, Cao X, Gilbert SR, Bouxsein ML, Faugere MC, Guldberg RE, Gerstenfeld LC, Haase VH, Johnson RS, Schipani E, Clemens TL. The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1616–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI31581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giaccia A, Siim BG, Johnson RS. HIF-1 as a target for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:803–11. doi: 10.1038/nrd1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaelin WG., Jr How oxygen makes its presence felt. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1441–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.1003602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Simon MC. Regulation of transcription and translation by hypoxia. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:492–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.6.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan C, Gilbert SR, Wang Y, Cao X, Shen X, Ramaswamy G, Jacobsen KA, Alaql ZS, Eberhardt AW, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA, Deng L, Clemens TL. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:686–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708474105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobsen KA, Al-Aql ZS, Wan C, Fitch JL, Stapleton SN, Mason ZD, Cole RM, Gilbert SR, Clemens TL, Morgan EF, Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Bone formation during distraction osteogenesis is dependent on both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:596–609. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleinheinz J, Stratmann U, Joos U, Wiesmann HP. VEGF-activated angiogenesis during bone regeneration. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.05.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farberg AS, Jing XL, Monson LA, Donneys A, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Deshpande SS, Buchman SR. Deferoxamine reverses radiation induced hypovascularity during bone regeneration and repair in the murine mandible. Bone. 2012;50:1184–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotz W, Reichert C, Canullo L, Jager A, Heinemann F. Coupling of osteogenesis and angiogenesis in bone substitute healing - a brief overview. Ann Anat. 2012;194:171–3. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schipani E, Maes C, Carmeliet G, Semenza GL. Regulation of osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling by HIFs and VEGF. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1347–53. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prisby R, Guignandon A, Vanden-Bossche A, Mac-Way F, Linossier MT, Thomas M, Laroche N, Malaval L, Langer M, Peter ZA, Peyrin F, Vico L, Lafage-Proust MH. Intermittent PTH(1-84) is osteoanabolic but not osteoangiogenic and relocates bone marrow blood vessels closer to bone-forming sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2583–96. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rashid G, Bernheim J, Green J, Benchetrit S. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the endothelial expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong L, Buchman SR. Facial bone grafts: Contemporary science and thought. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 2000;6:31–41. discussion 42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan WG, Szwajkun PR. Revascularization of cranial versus iliac crest bone grafts in the rat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1105–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199106000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burchardt H. Biology of bone transplantation. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18:187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevenson S, Emery SE, Goldberg VM. Factors affecting bone graft incorporation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996:66–74. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vahle JL, Sato M, Long GG, Young JK, Francis PC, Engelhardt JA, Westmore MS, Linda Y, Nold JB. Skeletal changes in rats given daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34) for 2 years and relevance to human safety. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30:312–21. doi: 10.1080/01926230252929882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vahle JL, Long GG, Sandusky G, Westmore M, Ma YL, Sato M. Bone neoplasms in F344 rats given teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] are dependent on duration of treatment and dose. Toxicol Pathol. 2004;32:426–38. doi: 10.1080/01926230490462138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vahle JL, Zuehlke U, Schmidt A, Westmore M, Chen P, Sato M. Lack of bone neoplasms and persistence of bone efficacy in cynomolgus macaques after long-term treatment with teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:2033–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tashjian AH, Jr, Chabner BA. Commentary on clinical safety of recombinant human parathyroid hormone 1-34 in the treatment of osteoporosis in men and postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1151–61. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harper KD, Krege JH, Marcus R, Mitlak BH. Osteosarcoma and teriparatide? J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:334. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andrews EB, Gilsenan AW, Midkiff K, Sherrill B, Wu Y, Mann BH, Masica D. The US postmarketing surveillance study of adult osteosarcoma and teriparatide: Study design and findings from the first 7 years. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:2429–37. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]