Abstract

Arsenite exposure is associated with an increased risk of human lung cancer. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the arsenite-induced human lung carcinogenesis remain elusive. In this study, we demonstrated that arsenite upregulates cyclin D1 expression/activity to promote the growth of human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells. In this process, the JNKs (c-Jun N-terminal kinases)/c-Jun cascade is elicited. The inhibition of JNKs or c-Jun by chemical or genetic inhibitors blocks the cyclin D1 induction mediated by arsenite. Furthermore, using a loss of function mutant of p85 (Δp85, a subunit of PI3K) or dominant-negative Akt (DN-Akt), we showed that PI3K and Akt act as the upstream regulators of JNKs and c-Jun in arsenite-mediated growth promotion. Overall, our data suggest a pathway of PI-3K/Akt/JNK/c-Jun/cylin D1 signaling in response to arsenite in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Keywords: PI-3K, Akt, JNK, c-Jun, cyclin D1, arsenite, cell proliferation

INTRODUCTION

Arsenic is an environmental toxin widely distributed in water, air, food and soil [1, 2]. Humans are exposed to arsenic mainly by inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact [3, 4]. The inhalation route mainly occurs by occupational exposure of ore smelters, insecticide manufacturers, and sheep dip workers, whose jobs have been associated with an increased risk of lung cancers [3, 4]. Although efforts have been made, the precise mechanisms of the arsenite-induced lung carcinogenesis remain enigmatic. Given the low genotoxic activity, arsenite is thought to exert its carcinogenic effect mainly through inducing epigenetic alterations, including activation of signal pathways that thereby affect the expression of genes involved in regulating the machineries of the cell cycle [5].

Cell cycle alternation and proliferation are controlled by a group of proteins, including cyclins. Cyclin D1, acting as a sensor in response to extracellular changes, can be induced by growth factors and stress [6]. Aberrant cyclin D1 expression is an early event in carcinogenesis [7] that often accompanies human malignancies in the ovary [8], breast [9], urinary bladder [10], skin [11] or lung [12]. Treatment with cyclin D1 anti-sense oligos has been shown to reverse the tumor-related phenotype of human colon cancer and squamous carcinomas [13]. Carcinogenic reagents are often able to induce cyclin D1 expression, which in turn promotes tumor growth [14]. Our previous study has shown that arsenite was able to induce cyclin D1 expression in human keratinocyte HaCat and mouse epidermal Cl41 cells to promote cell cycle transition, cell proliferation and transformation, which accounts for its ability to induce skin carcinogenesis [15–17]. In this study, we further investigated the effect of arsenite on cyclin D1 induction in human bronchial epithelial cells. The signaling pathway involved in the upregulation of cyclin D1 and subsequent growth promotion mediated by arsenite were thoroughly examined in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Reagents

Human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells, JNK1 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (JNK1−/−) and JNK2 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (JNK2−/−) were cultured in monolayers at 37°C, 5% CO2 using DMEM (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 25 μg of gentamicin/ml. The cultures were detached with trypsin and transferred to new 75-cm2 culture flasks (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) from one to three times per week. FBS was purchased from Life Technologies, Inc.; Luciferase assay kit was from Promega. Arsenite (As3+) was purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit was from Promega (Madison, WI). Antibodies specific targeting phospho- and total-Akt, p70S6k and MAP kinase family members, including ERKs and JNKs, were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Berverly, MA); antibody against β-Actin was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); and antibody against Cyclin D1 was purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cyclin D1 Promoter Luciferase Reporter

The cyclin D1 promoter-driven luciferase reporter (cyclin D1 Luc) was constructed by inserting a 1.23 kb EcoR I-Pvu II fragment of the cyclin D1 gene promoter, which contains the cyclin D1 promoter sequence from −1095 to +135 relative to the translation initiation site, into the pA3LUC vector as described previously [15, 16]. The specific small interference RNA (siRNA) targeting human cyclin D1 expression plasmid (designated as siCyclin D1) was described previously [18].

Stable Transfection

Beas-2B cells were transfected with 10 μg cyclin D1-luciferase reporter, hygromycine B resistant LacZ plasmid in combination with Δp85 plasmid, siCyclin D1 or DN-Akt plasmid, mixed together with LipofectAMINE transfection kit (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, hygromycin B selection and identification, stable transfectants including Beas-2B cyclinD1-Luc mass1, Beas-2B DN-Akt cyclinD1-Luc mass1, Beas-2B Δp85 cyclin D1-Luc mass1 and Beas-2B siCyclinD1 mass1 were established. The stable transfectants for the luciferase reporters were identified by measuring the basal level of luciferase activity, and the stable transfectants of Δp85 or DN-Akt were verified by analyzing the phosphorylation of Akt using Western blot. Beas-2B siCyclinD1 mass1 was identified by measuring the arsenite-induced cyclin D1 protein expression. Stable transfectants were cultured in hygromycin-free DMEM for at least two passages before experimentation.

Cell Proliferation Analysis

Beas-2B cells (2 × 103) and their stable transfectants were cultured in each well of 96-well plates to 30–40% confluence in 10% FBS DMEM. The cell culture medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS DMEM and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then exposed to arsenite for various time points followed by determination of ATP activity using CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit with a Luminometer (LB 96V multipliable counter system). The results are expressed as proliferation index relative to medium control.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Beas-2B cells (2 × 105) were cultured in each well of 6-well plates to 70–80% confluence with normal culture medium. The cell culture medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS DMEM for 24 h and then treated with arsenite for 24h. The cells were harvested and fixed with 3 ml of ice-cold 80% ethanol overnight. The fixed cells were then centrifuged (3000 rpm, 3 min), suspended in lysis buffer (100mM sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Then the cells were incubated with RNAse A (10 μg/ml) (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min at room temperature and DNA was stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) for at least 1 h at 4 °C. The DNA content was determined by flow cytometry using the Epics XL FACS (Beckamn Coulter) and EXPO 32 software.

Gene Reporter Assay

8×103 viable cells suspended in 100 μl 10% FBS DMEM were seeded into each well of 96-well plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After the cell density reached 80–90%, cells were exposed to arsenite for various time points, then lysed with 50 μl lysis buffer, and the luciferase activity was measured using the Promega Luciferase assay reagent with a luminometer (LB 96-V multipliable counter system). The results are expressed as cyclin D1 induction relative to medium control (relative cyclin D1 induction) as described before [15].

Western Blot

Beas-2B (2 × 105) or its transfectants were cultured in each well of 6-well plates to 70–80% confluence, then the culture medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS DMEM. After being incubated for 24 h, the cells were exposed to arsenite for 12 h or 24 h. The cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and extracted with SDS-sample buffer. The cell extracts were separated on polyacrylamide-SDS gels, transferred, and probed with a rabbit-specific primary antibody. The protein band, specifically bound to the primary antibody, was detected using an anti-rabbit IgG-AP-linked second antibody and an ECF Western blotting system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) [16].

Statistical Analysis

The significance of the difference between the treated and untreated groups was determined with the Student’s t test. The results are expressed as mean ± S.D.

RESULTS

Arsenite Promotes Beas-2B Cell Growth

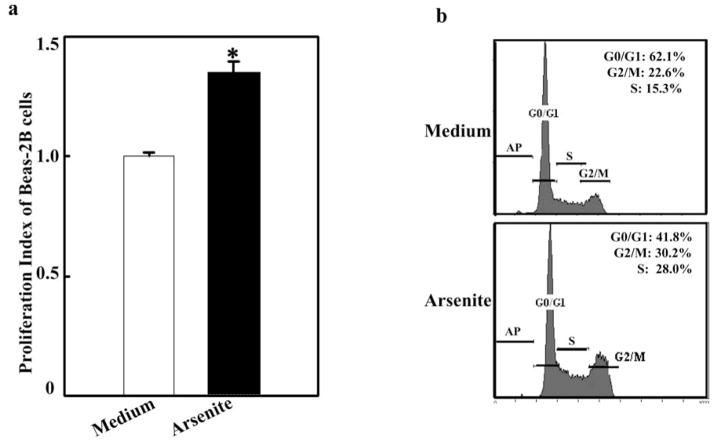

Arsenite has been thought to be a human lung carcinogen [16]. To investigate arsenite-induced lung tumorigenesis, human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells were exposed to arsenite for 48 h, and cell proliferation induced by arsenite was evaluated using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay that measures the level of ATP as an indicator of cell growth. As shown in Fig. (1a), exposure to arsenite led to a significant increase in the growth rate of the cells (about 33.4%), suggesting that arsenite exposure promoted proliferation in lung bronchial epithelial cells. The cell cycle progression upon arsenite treatment was also determined by a flow cytometer (Fig. 1b). The percentage of the treated cells in the S and G2/M phases was increased in comparison with that of the medium control. Those data indicate that arsenite exposure induces the cell cycle transition, resulting in growth promotion of human bronchial epithelial cells.

Fig. 1. Arsenite induces Beas-2B cell to proliferate.

a. Beas-2B cells (1 × 103) were seeded into a 96-well plate and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37°C overnight. Following 24 h of serum starvation (DMEM containing 0.1% FBS), the cells were treated with arsenite (1.25 μM) for 48 h. Subsequently, ATP assay was performed. Symbol of “*” indicated significant increase from medium control. b. The cells (2 × 105) were seeded into a 6-well plate and cultured overnight. Following serum starvation for 24 h, the cells were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 24 h and stained with propidium iodide for cell cycle analysis. Three independent experiments were performed.

Arsenite Promotes Beas-2B Cell Growth through Upregulating Cyclin D1

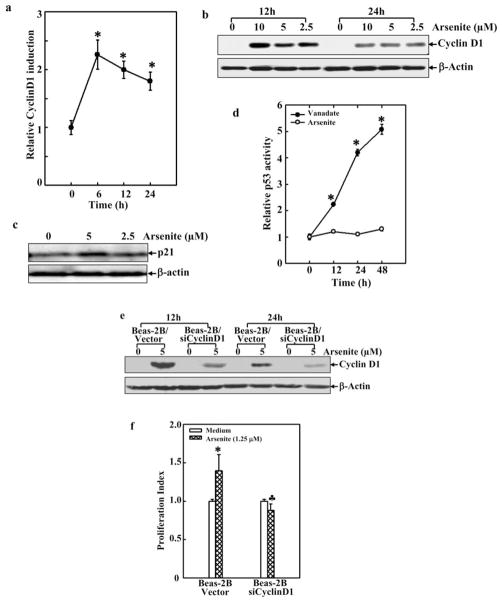

It is well known that cyclin D1, via interacting with CDK4 or CDK6, regulates cell cycle progression [18], and an increase in cyclin D1 expression by treatment with arsenite has been reported in various types of cells [15, 16], but not in the cells from the lung yet. Because the inhalation route of arsenite into the human body is mainly through the bronchial passages and lungs, we examined whether arsenite could also desregulate cyclin D1 and Beas-2B cell growth. The cyclin D1 expression at the transcription level, following arsenite treatment, was analyzed by a luciferase assay, in which the expression of luciferase is driven by the promoter of cyclin D1 (Fig. 2a). In response to arsenite treatment, the promoter activity of cyclin D1 was augmented in a time-dependent manner. The expression of cyclin D1 was further examined by Western blot analysis, and the level of this G1 regulator was elevated after the treatment (Fig. 2b). p21 is an important, negative G1 regulator. We then tested p21 expression and the activity of p53 (an upstream mediator of p21) in Beas-2B cells with or without arsenite exposure. Our results showed that same doses arsenite (≤5 μM) treatment only led to a marginal p21 protein induction (Fig. 2c) and no effect on p53-dependent transcription activity (Fig. 2d), suggesting that p21 and p53 might not play a role in the cell proliferation and cell cycle alternation in cell response to arsenite observed in current studies (Fig. 2c and 2d). It should be noted that treatment of BEAS-2B cells with high doses arsenite (≥10 μM) increased in protein expression of both p21 and p53 (data not shown). To further evaluate the effect of cyclin D1 in arsenite-induced cell proliferation, a cyclin D1 siRNA construct was stably introduced into Beas-2B cells. The siRNA blocked the induction/expression of cyclin D1 (Fig. 2e). Concomitantly, the growth of arsenite-treated Beas-2B cells was also inhibited (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2. Cyclin D1 was responsible for arsenite-induced cell proliferation.

a. Beas-2B cells expressing a cyclin D1-Luc (8 × 103) were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. After overnight culturing, the cells were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for various time periods. The luciferase activity was then measured. SD represents the standard deviation from three independent experiments. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant increase from medium control (p< 0.05). b. The cells (2×105) were seeded into a 6-well plate and cultured overnight, then synchronized by 24 h-serum starvation and treated with arsenite at various concentrations as indicated for 12h and 24 h. Subsequently, cell extracts were separated on polyacrylamide-SDS gels and probed with antibodies. GADPH was used as a control for protein loading. c. The cells at about 70% confluence condition were starved for 24 h and treated with arsenite for another 24 h. Western blot was performed. d. Beas-2B cells expressing a p53-Luc (8 × 103) were treated with arsenite (5 μM) or Vanadate (100 μM) for various time points. The luciferase activity was then measured. e. Beas-2B siCyclinD1 mass1 cells and its control cells were cultured in 6-well plates. After synchronizing by serum starvation and treatment with arsenite, Western blot was performed. f. Beas-2B siCyclinD1 mass1 cells and its control cells were treated with arsenite for various time periods and ATP assay was performed. Symbol of “*” indicated significant increase from medium control; and symbol of “♣” indicated significant decrease as compared with that of control siRNA transfectant.

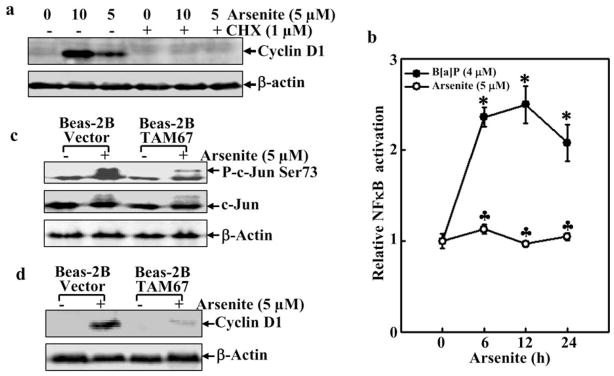

Induction of Cyclin D1 by Arsenite Requires c-Jun, but not NFκB

Cyclin D1 expression is regulated at either the transcriptional or translational level [15]. To determine whether new protein synthesis is required for the cyclin D1 induction by arsenite, the chemical inhibitor CHX was employed. Pre-treatment of cells with CHX completely inhibited cyclin D1 induction, suggesting that this arsenite-mediated cyclin D1 induction is dependent on new protein synthesis (Fig. 3a). The transcription of cyclin D1 has been shown to be regulated by multiple transcription factors (including NF-κB, AP-1, sp-1/sp-3, E2F/DP, STAT and CREB), depending on cell types and stimuli [19–23]. In human keratinocyte HaCat and murine epidermal Cl41 cells, NFκB and AP1 are involved in arsenite-induced upregulation of cyclin D1 [15, 16]. Therefore, we examined the status of NFκB or AP-1 in Beas-2B cells upon arsenite exposure. NFκB-dependent transcriptional activity was induced by B[a]P treatment, but not affected by arsenite exposure (Fig. 3b). The activation of c-Jun was tested using an antibody recognizing the phosphorylated Ser-73 of c-Jun (Fig. 3c). The phosphorylated form of c-Jun was detected in arsenite-treated cells. The introduction of a dominant negative mutant of c-Jun (TAM67) attenuated the phosphorylation of c-Jun and cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 3c and d). Our results demonstrate the involvement of c-Jun in arsenite-mediated cell cycle progression. Our previous studies have reported that late phase transcriptional expression of cyclin D1 could be indirectly regulated by NFAT in Cl41 cells exposed to B[a]PDE [24]. Since cyclin D1 maximal transcriptional expression occurs at 6 hrs after exposure (Fig. 2a), and NFAT activation occurs at 12 hrs after arsenite exposure [25], we also exclude the potential involvement of NFAT in arsenite-induced cyclin D1 upregulation.

Fig. 3. c-Jun is required for arsenite-mediated cyclin D1 induction.

a. After serum starvation, the cells were treated with CHX for 30 min prior to arsenite (5 μM) treatment. Western blot assay was then performed. b. Beas-2B NFκB Luc mass1 cells (8 × 103) were exposed to arsenite or B[a]P (a positive control) for various times. The luciferase activity was then measured. Symbol of “*” indicated significant increase from medium control. c. Beas-2B and Beas-2B TAM67 mass1 cells (2 × 105) were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 90 min. The phosphorylated c-Jun was detected by the antibody. d. Beas-2B cells and Beas-2B TAM67 mass1, following serum starvation, were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 24 h. Subsequently, Western blot was performed.

Involvement of JNK1 and JNK2 in Arsenite-Induced Cyclin D1 Expression

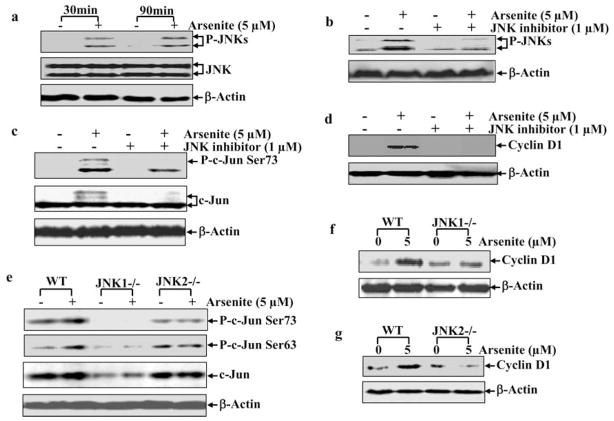

JNK1 and JNK2 are upstream kinases responsible for c-Jun phosphorylation in most stress responses [26, 27]. It has been reported that JNKs mediate the cyclin D1 expression in hematopoietic cells [28]. Therefore, we investigated the potential contribution of JNKs to cyclin D1 expression induced by arsenite. Exposure to arsenite stimulated the JNKs activation (Fig. 4a), and the inhibition of JNKS by their specific inhibitors (Fig. 4b) dramatically impaired arsenite-induced c-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. 4c) and cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 4d), suggesting that JNKs participate in arsenite-induced cyclin D1 expression. Since there are three isoforms of JNKs in mammalian cells, in which jnk1 and jnk2 are ubiquitously expressed, and jnk3 is selectively expressed in the brain, heart and testis [29], JNK1−/− and JNK2−/− MEFs were utilized (Fig. 4e, f and g). As shown in Fig. (4e), JNK1-deficiency resulted in dramatically reduction of basal level of C-Jun phosphorylation and arsenite-induced C-Jun phosphorylation, whereas JNK2-deficiency only impaired arsenite-induced C-Jun phosphorylation, but not basal level of C-Jun phosphorylation. These results strongly suggest that JNK1 is a major kinase responsible for maintaining the basal level of C-Jun phosphorylation, and both JNK1 and JNK2 are critical for arsenite-induced C-Jun phosphorylation. Consistent with C-Jun phosphorylation, the induction of cyclin D1 by arsenite was almost blocked in either JNK1−/− or JNK2−/− MEFs, suggesting that these two kinases are required for cyclin D1 induction following arsenite exposure.

Fig. 4. Essential role of JNK in arsenite-induced cyclinD1 expression.

a–g. Following serum starvation, the cells (2 × 105) with or without pretreatment with inhibitors, were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 90 min (a–c, e) or 12 h (d, f, g) and then subjected to Western blot analysis.

Involvement of the PI-3K/Akt/JNK Signaling Pathway in Arsenite-Mediated Growth Promotion

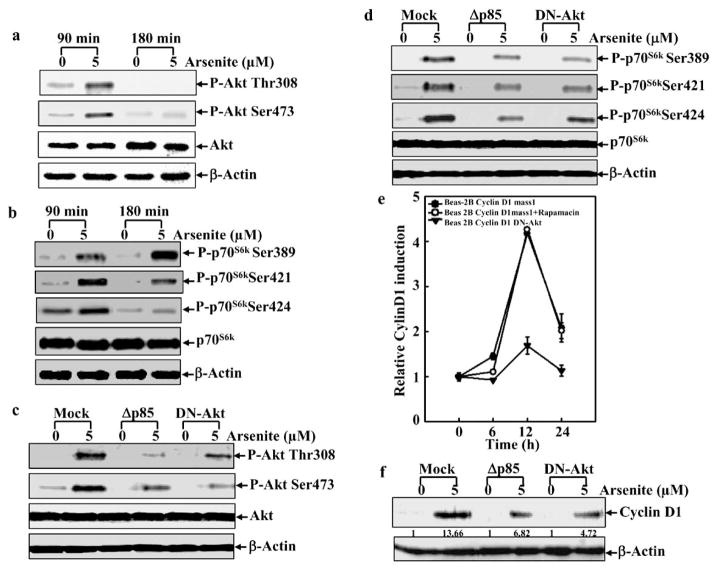

The PI3K/Akt pathway is activated in murine C141 or hepatocytes after the treatment with arsenite [16, 30]. We then tried to determine the influence of PI-3K/Akt signaling on Beas-2B cells with respect to growth promotion. Using the specific antibodies, we showed that arsenite exposure caused increase in the phosphorylation of Akt and p70s6k (Figs. 5a and b). Ectopic expression of Δp85 or DN-Akt inhibited arsenite-induced Akt activation and had less effect on p70S6K activation (Figs. 5c and 5d). It was noted that ectopic expression of Δp85 or DN-Akt did not show 100% inhibition of Akt activation. This is understandable because there are endogenous expression of p85α and Akt in BEAS-2B cells. Our results suggest that arsenite-induced Akt activation is mainly through PI-3K, and p70s6k activation may be through multiple pathways. Consistent with the inhibition of Akt activation, arsenite-induced cyclin D1 promoter transcription activity and protein expression was also reduced in both dominant negative transfectants (Figs. 5e and 5f). In contrast, the addition of rampmycin (an inhibitor of mTOR) to suppress the mTOR/p70S6K pathway had no effect on cyclin D1 promoter transcription activity (Fig. 5e), suggesting that arsenite-induced cyclin D1 upregulation is through an Akt-dependent and p70S6K-independent pathway.

Fig. 5. PI-3K/Akt pathway is involved in arsenite-mediated cyclin D1 induction.

a and b. Beas-2B cells were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 90 or 180 min., and then cell extracts were subjected to Western blot. c and d Beas-2B cells transfected with control vector, Δp85 or DN-Akt were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 60 min or 120 min and then Western blot was performed. e. Beas-2B cells transfected with control vector, or DN-Akt were pre-treated with rapamucin for 30 min and then exposed to arsenite (5 μM) for various times, and subsequently luciferase activity was measured. f. Beas-2B cells transfected with control vector, or DN-Akt were treated with arsenite (5 μM) for 24 h and Western blot was then performed. The number was the relative blots density of cyclin D1 compared to β-Actin.

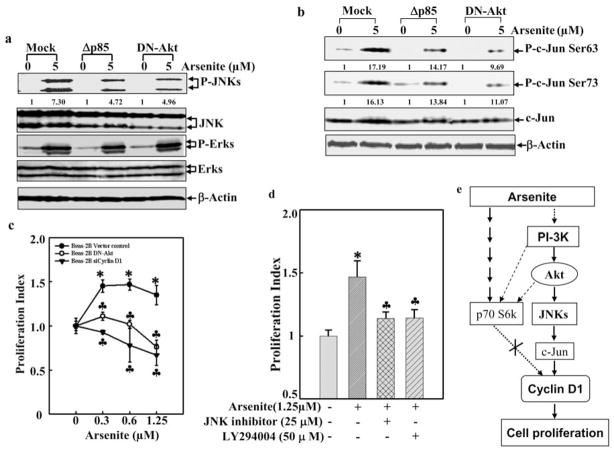

It has been shown previously that Akt acts upstream of JNKs in Cl41 cells following B[a]PDE exposure [31]. We further investigated the relationship between Akt and JNKs during arsenite-induced cyclin D1 expression in Beas-2B cells. The introduction of Δp85 or DN-Akt into the cells inhibited JNKs activation as well as c-Jun phosphorylation, whereas it did not affect ERKs activation (Figs. 6a and 6b). In addition, the growth promotion induced by arsenite was significantly inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 and JNK inhibitor (Fig. 6d), or by over expression of DN-Akt (Fig. 6c). Collectively, our results suggest that a signaling pathway leading to arsenite-induced growth promotion is through PI-3K/Akt/JNK/c-Jun/cyclinD1 in Beas-2B cells as illustrated in Fig. (6e).

Fig. 6. PI-3K/Akt/JNK pathway is implicated in arsenite-mediated cell proliferation.

a and b. Beas-2B cells transfected with control vector, Δp85 or DN-Akt were treated with arsenite for 60 min and Western blot was then performed. The number was the relative blots density phosphor-JNK or c-Jun compared with total JNK or c-Jun. c. Beas-2B cells transfected with control vector, or DN-Akt or siCyclin D1 were exposed to various doses of arsenite for 48 h and ATP assay was performed. d. Beas-2B cells (1 × 103) were pre-treated with JNK inhibitor (25 μM) or LY98059 (50 μM) for 30 min and then exposed to arsenite for 48 hrs. Subsequently, ATP assay was performed. e. illustration of signaling pathway leading to cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation upon arsenite exposure.

DISCUSSION

Arsenite has been classified as a human lung carcinogen [3–4]. Although previous studies including ours showed that alterations in cell cycle-related gene expressions induced by arsenite are responsible for growth promotion in human keratinocytes [16], it is still not known whether arsenite causes similar biological effects on cell proliferation and what the molecular mechanisms underlying arsenite-caused lung carcinogenesis are. Therefore, current studies we addressed those questions in human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells. We showed that arsenite exposure does upregulate cyclin D1 expression and further promote G1/S transition, and cell proliferation in BEAS-2B cells. We further found that the activation of JNKs and c-Jun are critical for those arsenite-mediated biological effects. Moreover, using a loss of function mutant Δp85 or DN-Akt, we demonstrated that the PI-3K/Akt pathway was involved in arsenite-induced upregulation of cyclin D1 and cell proliferation.

It is well documented the G1/S transition of the cell cycle is regulated by positive and negative regulators, such as cyclin D1 and p21 [32, 33]. Following forming complexes with CDK4/6, cyclin D1 phosphorylates the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor, which causes the dissociation and release of E2Fs to promote cell cycle progression [34]. p21, as a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, induces growth arrest by preventing the association of cyclin D1 with cdks. It has been thought that arsenite exposure is associated with an increased risk of human cancers, and alterations in cell cycle machinery are thought to be one of major factors implicated in its carcinogenic effect [35–37]. We have reported that arsenite exposure results in the induction of cyclin D1 expression and promotion of cell cycle progression, especially G1→S transition, cell proliferation and cell transformation in both human keratinocyte HaCat cells and mouse epidermal Cl41 cells [35–37], which is consistent with other finding that arsenite exposure could results in cyclin D1 induction with the inhibition of CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6 [38–40]. The cyclin D1 induction and increased G1→S transition by arsenite is dependent on the IKKβ/NF-κB pathway. Further, we show that cyclin D1 induction is responsible for the increased G1→S transition, cell proliferation and cell transformation demonstrated by the application of cyclin D1 specific small interference RNA (siRNA) [35, 36]. Our present studies demonstrate that cyclin D1 acts as a critical factor in arsenite-induced cell cycle transition and cell proliferation in Beas-2B cells.

Transcription factor p53 and its downstream target gene p21 play important role in the regulation of cell cycles. Liao et al. reported that arsenite exposure (≥5 μM) leads to weak increases in the protein expression of p53 and p21 in Beas-2B cells, while low doses of arsenite did not affect p53 and p21 expression [41]. They further showed that high doses arsenite-induced cell apoptosis was inhibited, while of centrosomal abnormality and anchorage-independent growth (colony formation) in p53 compromised cells (either with p53 dysfunction or inhibition) were increased [41], suggesting that arsenite at those high doses would act specifically on p53 compromised cells (either with p53 dysfunction or inhibited) to induce centrosomal abnormality and colony formation. Our present studies showed that relative low doses of arsenite (<5 μM) only have an marginal effect on p21 protein induction and no effect on p53-dependent transcriptional activity, whereas same doses of arsenite had remarked effects on cyclin D1 induction and significant effects on cell proliferation in BEAS-2B cells, indicating that at those low doses of arsenite exposure, p53 and p21 may not be major players in the regulation of cell cycle alternation and cell proliferation.

Studies have shown that cyclin D1 is regulated at the transcriptional level by multiple transcription factors, such as NFκB, AP-1, sp-1/sp-3, E2F/DP, STAT and CREB, in response to different cell types and stimuli [21–23]. It was also reported that STAT-binding sites were implicated in cytokine-induced transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 gene in hematopoietic cells [23]. Transcription factors, such as AP-1 or ATF/CREB, and Neu-related signaling have been demonstrated to be important in the regulation of cyclin D1 expression [42–44]. In the present study, we demonstrated that activation of c-Jun is required for arsenite-induced cyclin D1 expression. The activation of c-Jun is traditionally regulated by JNK [45]. JNK1 and JNK2, which were constitutively expressed in most tissues, have both overlapping and distinct functions in different cell lines [29]. However, in T lymphocytes, JNK1 and JNK2 have similar and stage-dependent roles in the induction of apoptosis and regulation of proliferation [46]. In contrast, in response to UV irradiation, these two kinases displayed quite distinct effects on apoptosis or cell proliferation [47]. Our study demonstrated that both JNK1 and JNK2 are required for arsenite-induced cyclinD1 expression.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the PI3K signal pathway plays a crucial role in eukaryotic cells by activating a set of transcription factors, including CREB and NF-κB, which in turn modulate the expression of various genes for cell proliferation, survival, and transformation [48]. PI3K and Akt have been shown to be able to activate IKK/NFκB [49], mTOR [50], MEK/ERKs/AP-1 [51] and GSK3β/β-catanin [52]. Using rapamycin to suppress mTOR, we excluded the possibility of this signal transducer in the regulation of arsenite-mediated cyclin D1 expression.

We previously demonstrated that JNK and c-Jun activation could be induced by the PI-3K/Akt signalling pathway in mouse Cl 41 cells exposed to PAHs. Here, we showed that arsenite, through the PI3K/Akt pathway, activated JNK and c-Jun for the upregulation of cyclin D1 in human bronchial Beas-2B cells. The identification of a PI-3K/Akt/JNK/c-Jun signaling axis delineates a hierarchy signaling chain reaction elicited by arsenite in the induction of cyclinD1 expression and further growth promotion. Our previous studies have demonstrated that ERKs activation, but not JNK activation, is critical for arsenite-induced mouse epidermal Cl41 cell transformation [41]. Considering current studies show the important role of JNKs in arsenite-induced Beas-2B cell proliferation, this is an another evidence supporting that signaling pathways involved in cell response to arsenite exposure might be different based on cell-type.

In summary, our current study demonstrates that arsenite exposure, via activating a growth-related signaling pathway, promotes human epithelial cell growth. In this process, the PI-3K/Akt/JNK/c-Jun pathway is involved. Our findings presented here greatly deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in arsenite induced lung carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT

NIH/NCI/NIEHS (CA094964, CA112557, ES012451, ES010344 and ES000260).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AP-1

activation protein-1

- CDKs

cyclin dependent kinases

- CREB

cAMP-responsive element binding protein

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase

- JNKs

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- NFκB

nuclear factor-kappaB

- PI-3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- siRNA

small interference RNA

References

- 1.Chappell WR, Beck BD, Brown KG, Chaney R, Cothern R, Cothern CR. Inorganic arsenic: a need and an opportunity to improve risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:1060–1067. doi: 10.1289/ehp.971051060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles FC, Benson AA. The enzyme inhibitory form of inorganic arsenic. Z Gesamte Hyg. 1984;30:625–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettley FR, O’Shea JA. The absorption of arsenic and its relation to carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:563–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landolph JR. Molecular mechanisms of transformation of C3H/10T1/2 C1 8 mouse embryo cells and diploid human fibroblasts by carcinogenic metal compounds. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 3):119–125. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández-Zavala A, Córdova E, Del Razo LM, Cebrián ME, Garrido E. Effects of arsenite on cell cycle progression in a human bladder cancer cell line. Toxicology. 2005;1:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winston JT, Pledger WJ. Growth factor regulation of cyclin D1 mRNA expression through protein synthesis-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1133–1144. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes DM, Gillett CE. Cyclin D1 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;52(1–3):1–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1006103831990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worsley SD, Ponder BA, Davies BR. Over expression of cyclin D1 in epithelial ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:189–1895. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michalides R, Hageman P, van Tinteren H, Houben L, Wientjens E, Klompmaker R. A clinicopathological study on over expression of cyclin D1 and of p53 in a series of 248 patients with operable breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:728–734. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor AJ, Coombs LM, Cairns JP, Knowles MA. Amplification at chromosome 11q13 in transitional cell tumors of the bladder. Oncogene. 1991;6:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnworth B, Popp S, Stark HJ, Steinkraus V, Bröcker EB, Hartschuh W, Birek C, Boukamp P. Gain of 11q/cyclin D1 overexpression is an essential early step in skin cancer development and causes abnormal tissue organization and differentiation. Oncogene. 2006;25:4399–4412. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauter ER, Nesbit M, Litwin S, Klein-Szanto AJ, Cheffetz S, Herlyn M. Antisense cyclin D1 induces apoptosis and tumor shrinkage in human squamous carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4876–4881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arber N, Doki Y, Han EK, Sgambato A, Zhou P, Kim NH. Antisense to cyclin D1 inhibits the growth and tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1569–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldin V, Lukas J, Marcote MJ, Pagano M, Draetta G. Cyclin D1 is a nuclear protein required for cell cycle progression in G1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:812–821. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouyang W, Ma Q, Li J, Zhang D, Liu ZG, Rustgi AK, Huang C. Cyclin D1 induction through IkappaB kinase beta/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway is responsible for arsenite-induced increased cell cycle G1-S phase transition in human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9287–9293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouyang W, Li J, Ma Q, Huang C. Essential roles of I-3K/Akt/IKKbeta/NFkappaB pathway in cyclin D1 induction by arsenite in JB6 Cl41 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):864–873. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan YX, Nakagawa H, Lee MH, Rustgi AK. Transforming growth factor-alpha enhances cyclin D1 transcription through the binding of early growth response protein to a cis-regulatory element in the cyclin D1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33181–33190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogt BL, Rossman TG. Effects of arsenite on p53, p21 and cyclin D expression in normal human fibroblasts -- a possible mechanism for arsenite’s comutagenicity. Mutat Res. 2001;478:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, Heder A, Scheidereit C, Strauss M. NF-κB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2690–2698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee RJ, Albanese C, Fu M, D’Amico M, Lin B, Watanabe G, Haines GK, 3rd, Siegel PM, Hung MC, Yarden Y, Horowitz JM, Muller WJ, Pestell RG. Cyclin D1 is required for transformation by activated Neu and is induced through an E2F-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:672–683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.672-683.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe G, Albanese C, Lee RJ, Reutens A, Vairo G, Henglein B, Pestell RG. Inhibition of cyclin D1 kinase activity is associated with E2F-mediated inhibition of cyclin D1 promoter activity through E2F and Sp1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3212–3222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee RJ, Albanese C, Stenger RJ, Watanabe G, Inghirami G, Haines GK, Webster M, Muller WJ, Brugge JS, Davis RJ, Pestell RG. pp60(v-src) induction of cyclin D1 requires collaborative interactions between the extracellular signal-regulated kinase, p38, and Jun kinase pathways. A role for cAMP response element-binding protein and activating transcription factor-2 in pp60(v-src) signaling in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7341–7350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumura I, Kitamura T, Wakao H, Tanaka H, Hashimoto K, Albanese C, Downward J, Pestell RG, Kanakura Y. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 promoter by STAT5: its involvement in cytokine-dependent growth of hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:1367–1377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J, Zhang R, Li J, Xue C, Huang C. Involvement of nuclear factor of activated T cells 3 (NFAT3) in cyclin D1 induction by B[a]PDE or B[a]PDE and ionizing radiation in mouse epidermal Cl 41 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;287:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding J, Li J, Xue C, Wu K, Ouyang W, Zhang D, Yan Y, Huang C. Cyclooxygenase-2 Induction by Arsenite Is through a Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cell-dependent Pathway and Plays an Antiapoptotic Role in Beas-2B Cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24405–24413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dérijard B, Hibi M, Wu IH, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis RJ. JNK1: A protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang C, Ma WY, Young MR, Colburn N, Dong Z. Shortage of mitogen-activated protein kinase is responsible for resistance to AP-1 transactivation and transformation in mouse JB6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:156–161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki T, Wada T, Kishimoto H, Irie-Sasaki J, Matsumoto G, Goto T, Yao Z, Wakeham A, Mak TW, Suzuki A, Cho SK, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Oliveirados-Santos AJ, Katada T, Nishina H, Penninger JM. The stress kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK)7 is a negative regulator of antigen receptor and growth factor receptor-induced proliferation in hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(6):757–768. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mielke K, Herdegen T. JNK and p38 stresskinases - degenerative effectors of signal-transduction-cascades in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haga S, Ogawa W, Ozaki M. Compensatory recovery of liver mass by Akt-mediated hepatocellular hypertrophy in liver-specific STAT3-deficient mice. J Hepatol. 2005;43(5):799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Chen H, Tang MS, Shi X, Amin S, Desai D, Costa M, Huang C. PI-3K and Akt are mediators of AP-1 induction by 5-MCDE in mouse epidermal Cl41 cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;165:77–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stacey DW. Cyclin D1 serves as a cell cycle regulatory switch in actively proliferating cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:158–163. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semczuk A, Jakowicki JA. Alterations of pRb1-cyclin D1-cdk4/6-p16INK4A pathway in endometrial carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2003;203:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouyang W, Luo W, Zhang D, Jian J, Ma Q, Li J, Shi X, Chen J, Gao J, Huang C. PI-3K/Akt pathway-dependent cyclin D1 expression is responsible for arsenite-induced human keratinocyte transformation. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ouyang W, Li J, Zhang D, Jiang BH, Huang DC. PI-3K/Akt signal pathway plays a crucial role in arsenite-induced cell proliferation of human keratinocytes through induction of cyclin D1. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:969–978. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang C, Ma WY, Li J, Goranson A, Dong Z. Requirement of Erk, but Not JNK, for Arsenite-induced Cell Transformation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14595–14601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JY, Choi JA, Kim TH, Yoo YD, Kim JI, Lee YJ, Yoo SY, Cho CK, Lee YS, Lee SJ. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the cell growth inhibition by sodium arsenite. J Cell Phys. 2002;190:29–37. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arteel GE, Guo L, Schlierf T, Beier JI, Kaiser JP, Chen TS, Liu M, Conklin DJ, Miller HL, von Montfort C, States JC. Subhepatotoxic exposure to arsenic enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2008;226:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehmann GM, McCabe MJ., Jr Arsenite slows S phase progression via inhibition of cdc25A dual specificity phosphatase gene transcription. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99:70–78. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao WT, Lin P, Cheng TS, Yu HS, Chang LW. Arsenic promotes centrosome abnormalities and cell colony formation in p53 compromised human lung cells. Toxicol Appl Pharma. 2007;225:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe G, Lee RJ, Albanese C, Rainey WE, Batlle D, Pestell RG. Angiotensin II activation of cyclin D1-dependent kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22570–22577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Jin B, Huang C. The PI3K/Akt pathway and its downstream transcriptional factors as targets for chemoprevention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:305–316. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagata D, Suzuki E, Nishimatsu H, Satonaka H, Goto A, Omata M, Hirata Y. Transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 gene is mediated by multiple cis-elements, including SP1 sites and a cAMP-responsive element in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:662–669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabapathy K, Hochedlinger K, Nam SY, Bauer A, Karin M, Wagner EF. Distinct Roles for JNK1 and JNK2 in regulating JNK activity and c-Jun-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabapathy K, Kallunki T, David JP, Graef I, Karin M, Wagner EF. c-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase (JNK)1 and JNK2 Have Similar and Stage-dependent Roles in Regulating T Cell Apoptosis and Proliferation. J Exp Med. 2001;193:317–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hochedlinger K, Wagner EF, Sabapathy K. Differential effects of JNK1 and JNK2 on signal specific induction of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:2441–2445. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunet A, Datta SR, Greenberg ME. Transcription-dependent and -independent control of neuronal survival by the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:297–305. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manning BD, Cantley LC. United at last: the tuberous sclerosis complex gene products connect the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:573–578. doi: 10.1042/bst0310573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eder AM, Dominguez L, Franke TF, Ashwell JD. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulation of T cell receptor-mediated inter-leukin-2 gene expression in normal T cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28025–28031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryves WJ, Harwood AJ. The interaction of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) with the cell cycle. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]