Abstract

Metabolic rate determines the physiological and life-history performances of ectotherms. Thus, the extent to which such rates are sensitive and plastic to environmental perturbation is central to an organism's ability to function in a changing environment. Little is known of long-term metabolic plasticity and potential for metabolic adaptation in marine ectotherms exposed to elevated pCO2. Consequently, we carried out a series of in situ transplant experiments using a number of tolerant and sensitive polychaete species living around a natural CO2 vent system. Here, we show that a marine metazoan (i.e. Platynereis dumerilii) was able to adapt to chronic and elevated levels of pCO2. The vent population of P. dumerilii was physiologically and genetically different from nearby populations that experience low pCO2, as well as smaller in body size. By contrast, different populations of Amphiglena mediterranea showed marked physiological plasticity indicating that adaptation or acclimatization are both viable strategies for the successful colonization of elevated pCO2 environments. In addition, sensitive species showed either a reduced or increased metabolism when exposed acutely to elevated pCO2. Our findings may help explain, from a metabolic perspective, the occurrence of past mass extinction, as well as shed light on alternative pathways of resilience in species facing ongoing ocean acidification.

Keywords: adaptation, plasticity, climate change, metabolic rate, ocean acidification, mass extinction

1. Introduction

Metabolic rate is considered the most fundamental of all biological rates [1]. According to the metabolic theory of ecology, metabolic rates set the rates of resource uptake and allocation to life-history traits (such as growth, reproduction and survival [2]), ultimately controlling ecological processes at all levels of organization [1]. Thus, the ability of an organism to preserve sufficient levels of energy metabolism when exposed to environmental challenges is key to a species' ability to preserve positive life-history traits, its Darwinian fitness, and ultimately its distribution and abundance patterns locally and globally [1,3–7].

Investigations of the effects of elevated pCO2 on ectotherms' metabolic rates have revealed a variety of different responses: from differences among phyla at one extreme [8–10], to differences among related species and populations at the other [11,12]. When exposed to elevated pCO2, a number of taxa exhibit a marked downregulation of their metabolic rate or ‘metabolic depression’ [11,13–17] but this is not ubiquitous. There are examples of upregulation [18–20], and no change in metabolism in response to elevated pCO2 [11,21–24]. It has been proposed that metabolic depression evolved to enable organisms to maintain a balance between energy supply and demand when their physiological machinery may be impaired as a result of environmental challenges [25,26]. Consequently, metabolic depression is considered to be primarily a short-term strategy [27] as, over the long term, it may have high costs in terms of growth, performances, reproductive output and may ultimately affect fitness. Thus, chronic metabolic depression has the potential to limit or prevent colonization of elevated pCO2 environments, and in a future, more acidic ocean to increase the risk of local and global taxa extinction. However, moderate forms of metabolic depression may be sustainable and could be achieved, via adaptation (i.e. selection of phenotypes–genotypes with moderately lower metabolic rates) or acclimatization (i.e. via phenotypic plasticity [28]). Nevertheless, adaptation and acclimatization can have different and important ecological consequences. Unfortunately, the nature and significance of physiological plasticity in marine ectotherms during acclimatization to an elevated pCO2 environment, as well as their potential physiological adaptation to these conditions, remain virtually unexplored (cf. [29]). Such an understanding of when plastic as opposed to genetic changes occur (and vice versa) is crucial if we are to predict how ocean acidification affects species' distribution and abundance patterns, and thus predict the likely responses of marine ectotherms to ongoing climate change.

In addition, our interpretation of organisms' metabolic responses to elevated pCO2 is biased by the fact that most species investigated to date are calcifiers. This is important as the overall direction and intensity of metabolic responses to elevated pCO2 are potentially affected by the upregulation of calcium carbon deposition [30–32], as well as the need to alter the biomineralization status of the shell, which may require the production of different organic and inorganic components [33], processes which are to date still poorly understood from a metabolic point of view. Furthermore, phylogenetic independence is rarely accounted for [10,34–37, cf. 38]. Clearly, there is an urgent need to investigate the physiological acclimatory ability and potential for physiological adaptation in a range of species within a group of phylogenetically related, non-calcifying ectotherms.

Consequently, we investigated the effect of elevated pCO2 on the metabolic rates of a number of species of non-calcifying polychaetes, which live in different proximities to natural CO2 vents. Polychaetes, in general, have so far received relatively little attention when compared with other groups (e.g. molluscs and crustaceans) (cf. [39–41]). Here using field transplant experiments, we looked for evidence of physiological acclimatization or adaptation in these species.

The CO2 vents of Ischia (Naples, Italy) have been used extensively to investigate the effects of elevated pCO2/low pH conditions on marine communities and to predict possible responses of marine ecosystems to ocean acidification [10,42–45]. Used carefully, areas naturally enriched in CO2 make ideal natural laboratories for investigating such evolutionary questions. Cigliano et al. [43] found species-specific patterns of settlement in invertebrates along CO2 gradients in this vent system, mirrored by patterns of presence/absence and abundance of adults of polychaete species in the hard bottom community [43,45], potentially indicating the presence of adaptation or acclimatization. In particular, around the CO2 vents of Ischia, some polychaete species maintain high densities along pCO2 gradients or even increase in density the closer they are to the vents. Such species could be considered as ‘tolerant’ [36]. Others decrease in density progressively along the CO2 gradients and are absent from the elevated pCO2 areas within the vents. These species could be considered ‘sensitive’ [36]. Given that there are such tolerant and sensitive non-calcifying polychaetes around the vents, the polychaete assemblage in Ischia is an ideal study system to test whether the ability of marine ectotherms to colonize CO2 vents depends on their different scope for physiological acclimatization and/or adaptation to elevated pCO2 conditions.

To define the potential for metabolic acclimatization and adaptation that allows colonization of elevated pCO2 areas, we carried out a series of in situ transplant and mutual transplant experiments populated with polychaetes living around the shallow-water CO2 vents system off Ischia. Post-transplant, we characterized metabolic rates and responses of the polychaetes, allowing us to infer the potential for metabolic adaptation in tolerant versus sensitive species (experiment 1), as well as between populations of tolerant species found both inside and outside the vent areas (experiment 2). Finally, to explore the evolutionary implications of any potential physiological adaptation of different populations of tolerant species, we used putatively neutral molecular markers to attribute levels of relatedness and phylogeographic pattern in populations of two of the tolerant species collected at increasing distance from the vents.

We predicted that (i) tolerant polychaete species will maintain their metabolism following acclimatization/adaptation to elevated pCO2 conditions (type 2 acclimatization/adaptation sensu [46]), (ii) sensitive polychaete species will display metabolic depression (type 1 acclimatization/adaptation sensu [46]).

2. Material and methods

(a). Selection of sensitive and tolerant species

Two groups of species were identified:

(i) ‘Tolerant’ to low pH/elevated pCO2 conditions: species abundant both outside and inside the low pH/elevated pCO2 areas of the Castello CO2 vents of Ischia, namely Platynereis dumerilii (Audouin & Milne-Edwards, 1834; Nereididae), Amphiglena mediterranea (Leydig, 1851; Sabellidae), Syllis prolifera (Krohn, 1852; Syllidae) and Polyophthalmus pictus (Dujardin, 1839; Opheliidae). The first three dominate the most intense venting areas [43,45] and are commonly associated with rocky, shallow, vegetated habitat in the Mediterranean and with Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile, 1813 seagrass beds [47–49]. P. dumerilii and S. prolifera are mesoherbivores, whereas A. mediterranea is a filter feeder. The fourth species, P. pictus (Opheliidae), is also a mesoherbivore typical of shallow, vegetated habitats [47]. This species was relatively scarce in the acidified areas in previous studies [43,45], but found (after our work took place) to be abundant on macroalgae and dead matter in a P. oceanica bed in high venting areas (E. Ricevuto & M. C. Gambi 2013, personal communication).

(ii) ‘Sensitive’ to low pH/elevated pCO2 conditions: species occurring around the vents under higher pH/low pCO2 conditions, but largely absent in the vents areas [43], namely Lysidice ninetta (Audouin & Milne-Edwards, 1833; Eunicidae), Lysidice collaris (Grube, 1870; Eunicidae) and Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin, 1791; Sabellidae). Both Lysidice species are associated with vegetated rocky reef and coralligenous formations and are some of the few species that bore on P. oceanica seagrass sheaths [50]. They also occur in the P. oceanica meadows at depths of 3–5 m and surrounding the vents, where normal pH/low pCO2 conditions exist [51]. Finally, S. spallanzanii is one of the most common and conspicuous sabellids in the Mediterranean. It is a filter feeder, tolerant to organic pollution and typical of fouling communities [52,53] outside the Ischia vent area [42]. All the sensitive species occur around the vents, in similar shallow habitat, but do not colonize the low pH/elevated pCO2 areas, thus suggesting that these conditions may constrain their distribution.

(b). Collection details

The four tolerant species live in association with various macroalgae (mainly Dyctiota spp., Halopteris scoparia and Cladophora prolifera), where they were collected by hand, either by means of snorkelling or scuba diving, in both elevated (i) and low (ii) pCO2 conditions:

(i) at 1–2 m depth on a rocky reef at the low pH area on the south side of the Castello Aragonese, Ischia, Naples (40°43.84 N, 13°57.08 E). The collection area (Castello S3 in [43]) is approximately 60 × 15 m along a rocky reef and in the nearby P. oceanica meadow and dead ‘matte’. This area corresponds to the very low pH area described in [45], where the pH ranges between 7.3 and 6.6 [45].

(ii) at 1–2 m depth off San Pietro promontory (approx. 4 km from the vents), where the control site experiments were performed, and around Sant'Anna islets and Cartaromana Bay (about 600 m from the vents). Here, venting activities were absent and water pH values measured were representative of low pCO2 conditions (mean pH 8.17 ± 0.02 at S. Pietro and 8.07 ± 0.002 at S. Anna, [45]). At these sites, polychaetes were associated with the same macroalgae species mentioned earlier, as well as with Corallina sp. Polychaetes from both localities were mixed and haphazardly allocated to different treatment and stations (see below). Finally, note that S. prolifera could not be retrieved from low pCO2 areas at the time our work was carried out, despite having been collected during previous studies and surveys [43,45] and in more recent times.

The sensitive species were collected exclusively in low pCO2/high pH conditions. Specifically, S. spallanzanii was collected from floating docks in Ischia harbour, where this species form a dense population in the fouling community and thus a sufficient number of individuals for our experiment could be found. The two borer species of Lysidice were collected in shallow P. oceanica meadow (10 m depth) off Cava beach (approx. 10 km from the vents), a unique site in the area where these species occur in sufficient number in P. oceanica shoots [50].

The molecular phylogenetic analyses were conducted only on the tolerant species, A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii. Specimens of both taxa were collected at two acidified sites (Castello N3 and Castello S3 sensu [43]) and at several low pCO2 sites at different distances from the vents; P. dumerilii was also collected from the Bristol Channel, UK (see the electronic supplementary material, table A1.1 in appendix 1). Individuals of each species (n = 7–29) were collected at each location for genetic analyses. All specimens of A. mediterranea were preserved in 95% ethanol. Specimens of P. dumerilii were preserved in 95% ethanol or in dimethyl sulfoxide, frozen at −80°C or immediately processed after collection without prior preservation. All A. mediterranea specimens were processed at Texas A&M University at Galveston (TAMUG; Galveston, USA); all P. dumerilii specimens were processed at the University of Hull (Hull, UK).

(c). Culture and pre-exposure of polychaetes

To provide material for use in transplant experiments, all specimens of all species were reared in glass bowls (approx. 20 individual per bowl), each containing 300 ml of natural seawater (S = 38) at the original seawater pH/pCO2. All glass bowls were kept in a controlled temperature environment (T = 19°C, 12 L : 12 D cycle). Each bowl was supplied with a few pieces of macroalgae from the collection site, for the polychaete to attach to and feed upon. Individuals of S. spallanzani were kept under identical conditions except that, owing to their larger body size, the containers used were larger (volume = 14 l, approx. 1.2 individuals per litre), to allow polychaetes to easily open the branchial crown for filtering and respiration.

(d). Study area and methods

The area where the transplant experiments into acidified conditions (A) were carried out was located in zones of high venting activity (greater than 10 vents m−2), at both south and north sides of the Castello Aragonese d'Ischia (figure 1). Previous studies showed a persistent gradient of low pH conditions in these areas [45]. In particular, three stations (A1, A2, A3—depth 2.5 m, areas approx. 2 × 3 m wide) were selected (figure 1), effectively representing one locality. The control area (C) (San Pietro point, approx. 4 km from the vent area; figure 1) was situated in close proximity to the Benthic Ecology research unit (Villa Dohrn) and was selected because of the persistent high pH/low pCO2 conditions and its accessibility [44]. Three stations (C1, C2 and C3—3 m depth) were established approximately 50 m apart from each other (figure 1). Small stony moorings (mass = 6 kg) were deployed in each of the six stations employed. A buoy attached to a nylon rope was used to fix, via a plastic cable tie, the experimental containers (‘transplantation chambers’) where individuals of the study species were kept during the experiment. Transplantation chambers for all but one species were constructed from white PVC tubes (diameter = 4 cm, length = 11 cm) with a nytal plankton net (mesh = 100 µm) fixed to both ends. This net mesh size was small enough to prevent polychaete escaping but allow regular water flow through the tube, allowing filtration for filter-feeders and respiration. For mesograzers, some of the algae that the various specimens are found on in the field were introduced in the transplantation chambers to provide both a suitable substratum for the polychaete to attach onto and a source of food to graze upon for the entire duration of the transplant, as for sea urchins in [36]. The large filter feeding S. spallanzanii were inserted in larger transplantation chambers constructed as plastic mesh cages (diameter = 15 cm, length = 30 cm, mesh = 1 cm), through which the apical part of their tube protruded by 1 cm allowing the branchial crown to open outside the cage enabling filtering and respiration. In general, while feeding can affect an organism physiology, and in particular metabolic levels [54,55], here we specifically wanted to maintain the polychaetes in conditions as close as possible to those they experience in the field, where they have continuous access to food resources.

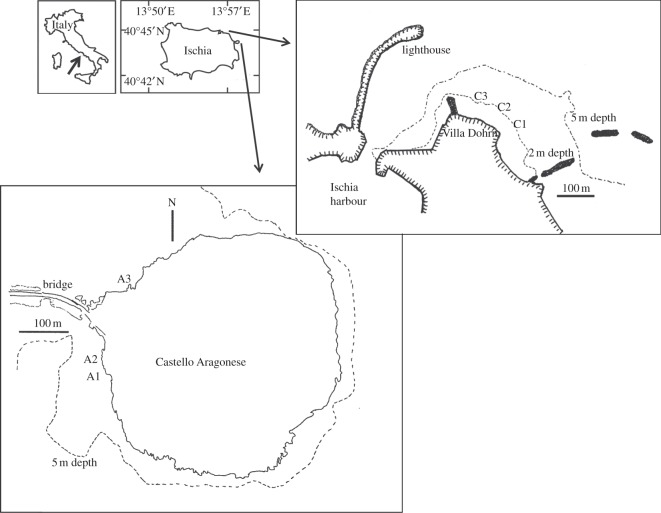

Figure 1.

Regional (left) and local (right) maps of the study area, showing the low (C1, C2, C3) and elevated (A1, A2, A3) pCO2 stations used for the in situ transplants of polychaete species in the area around the CO2 vents off Ischia (Naples, Italy). The dotted lines represent bathymetric lines.

(e). Transplant design

To investigate the potential for metabolic adaptation and acclimatization that may allow or prevent the successful colonization of elevated pCO2 areas, the effect of exposure to different pCO2 conditions on the metabolic rates of selected polychaete species, collected from either low or elevated pCO2 areas around the shallow-water CO2 vent system off Ischia, was examined using a two-way orthogonal experimental design (with ‘exposure’ (exposure to low and elevated pCO2) and ‘species’ as factors). The analyses were conducted separately for the transplant experiments (‘transplant from control areas’—experiment 1) and the reciprocal or mutual transplant (‘transplant from acidified areas’—experiment 2).

(i). Experiment 1

The first experiment investigated metabolic rates of all species collected from non-acidified conditions in control areas (control—C) that were exposed to acidified (C-A) and non-acidified (C-C) conditions in situ for five days. For each species separately, and at each station, transplantation chambers (average of four individuals per chamber and so approx. 12 individuals in total per species per treatment) were deployed by scuba diving.

(ii). Experiment 2

The second experiment investigated whether individuals of tolerant species living inside the CO2 vent areas show the same CO2-dependent metabolic rate response among each other and when compared with their conspecifics living outside the CO2 vents. We conducted the reciprocal in situ transplant experiment on specimens of tolerant species collected from inside the vents (acidified—A), following the same deployment procedure described above in acidified (A-A) and non-acidified (A-C) areas. S. prolifera was found only in acidified conditions, while P. pictus was not found in sufficient numbers in the acidified area, therefore reciprocal transplants were not possible for these two species.

(f). Environmental monitoring and profiles

Seawater pH, temperature and salinity were measured at each station daily throughout the three weeks duration of the experiments. For the transplant experiment, environmental monitoring was carried out as follows. pHNSB was measured using a pH microelectrode (Seven Easy pH InLab, Mettler-Toledo Ltd, Beaumont Leys, UK), maintained at ambient seawater temperature, coupled to a pH meter (Sevengo, Mettler-Toledo Ltd), calibrated using pH standards (pH 4.01, 7.00, 9.21 at 25°C, Mettler-Toledo Ltd) and also maintained at ambient seawater temperature. Temperature was measured using a digital thermometer (HH806AU, OMEGA Eng. Ltd, Manchester, UK).

Salinity was measured using a hand-held conductivity meter (TA 197 LFMulti350, WTW, Weilheim, Germany). In addition, to determine total alkalinity (TA), samples of seawater (volume = 100 ml) were collected at each station daily throughout the duration of the experimental period using glass bottles with a secure tight lid, transported inside a cool box to the laboratory (located approx. 4 km from the vents) and poisoned with HgCl2 within approximately 60 min of collection. TA was determined at the Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre at Plymouth University (Plymouth, UK), using an alkalinity titrator (AS-ALK2, Apollo SciTech, Bogart, USA).

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), calcite and aragonite saturation (Ωcalc and Ωara), bicarbonate and carbonate ion concentration ([HCO3–] and [CO32–], respectively) were calculated from pH and TA measurements using the software program CO2SYS [56] with dissociation constants from [57] refit by [58] and [KSO4] using [59]. Our results for the carbonate system (table 1) outside and inside the CO2 vent areas are consistent with those previously reported for these areas [42–45,60–62].

Table 1.

Values (mean ± s.e.) for physico-chemical parameters of the seawater used when exposing polychaetes to: (i) current pCO2/pH conditions (‘control’ stations C1, C2 and C3) and (ii) elevated pCO2/low pH conditions (‘acidified’ stations A1, A2, A3). Salinity, temperature, pHNBS (Mettler-Toledo pH meter, Luton, UK), TA (AS-ALK2, Apollo SciTech, Bogart, USA), DIC, carbon dioxide partial pressure (pCO2), bicarbonate and carbonate ion concentration ([HCO3–] and [CO32–), calcite and aragonite saturation state (Ωcal and Ωara) are provided.

| parameter | control |

acidified |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | overall | A1 | A2 | A3 | overall | |

| salinity | 37.50 ± 0.15(A) | 37.55 ± 0.16(A) | 37.55 ± 0.16(A) | 37.53 ± 0.09 | 37.19 ± 0.07(A) | 37.14 ± 0.05(A) | 37.10 ± 0.06(A) | 37.14 ± 0.03 |

| temperature (°C) | 22.83 ± 0.03(A) | 22.80 ± 0.03(A) | 22.80 ± 0.03(A) | 22.81 ± 0.02 | 23.33 ± 0.15(A) | 23.31 ± 0.12(A) | 23.41 ± 0.18(A) | 23.34 ± 0.08 |

| pH | 8.15 ± 0.01(A) | 8.16 ± 0.01(A) | 8.15 ± 0.01(A) | 8.15 ± 0.003 | 7.19 ± 0.05(B) | 7.07 ± 0.07(B) | 7.24 ± 0.04(B) | 7.17 ± 0.04 |

| TA (µequiv kg−1) | 2624.27 ± 10.34(A) | 2623.30 ± 10.76(A) | 2629.29 ± 8.91(A) | 2627.15 ± 5.26 | 2678.22 ± 3.78(A) | 2673.73 ± 12.57(A) | 2678.50 ± 12.90(A) | 2676.38 ± 6.41 |

| DIC (µmol kg−1)a | 2316.80 ± 7.68 | 2307 ± 11.09 | 2311.43 ± 8.74 | 2311.90 ± 5.21 | 2781.21 ± 20.15 | 2767.05 ± 23.75 | 2892.95 ± 55.51 | 2815 ± 22.81 |

| pCO2 (µatm)a | 483.68 ± 7.19 | 474.70 ± 8.64 | 447.53 ± 8.41 | 478.40 ± 4.55 | 5337.65 ± 567.54 | 5267.76 ± 493.97 | 8847.50 ± 1364.50 | 6534.16 ± 564.68 |

| [HCO3–] (µmol kg−¹)a | 2070.00 ± 9.50 | 2060.58 ± 0.05 | 2065.13 ± 9.29 | 2065.94 ± 5.43 | 2585.11 ± 6.87 | 2565.58 ± 20.72 | 2597.80 ± 20.28 | 2582.73 ± 10.29 |

| [CO32–] (µmol kg−¹)a | 231.18 ± 2.33 | 232.58 ± 3.08 | 232.23 ± 3.14 | 231.89 ± 1.62 | 38.30 ± 2.93 | 45.31 ± 7.10 | 33.23 ± 4.92 | 38.98 ± 3.15 |

| Ωcalb | 5.42 ± 0.06 | 5.47 ± 0.07 | 5.46 ± 0.08 | 5.45 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 0.78 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.07 |

| Ωarab | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 3.59 ± 0.05 | 3.59 ± 0.05 | 3.58 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

Different capital letters (A,B) indicate significant differences for measure parameters in different stations.

During the experimental period, seawater environmental conditions (table 1) were relatively stable with mean values for temperature, salinity and TA being around 23°C, 37 and 2651 µequiv kg−1, respectively. Mean pH values were relatively stable, approximately 8.15 and 7.17 for the control and acidified areas, respectively (table 1). Furthermore, preliminary analysis using the estimate marginal means (EMM) test with Bonferroni correction showed that environmental conditions (salinity, temperature and TA) were comparable across all stations irrespective of the pCO2 condition (table 1); while mean pH significantly differed among the low and elevated pCO2 treatments, it was, however, comparable among stations of a same treatment (table 1).

(g). Recovery of transplantation chambers and measurement of metabolic rates

After five days of exposure in situ to either acidified or control conditions, transplantation chambers from both experiments 1 and 2 were recovered via snorkelling and diving. They were transported within 5 min of harvest, using a bucket filled with seawater, to an aquarium containing seawater (volume = 60 l). Within 30 min of collection, all individuals were introduced individually, and in succession, to the incubation chambers (see below) containing filtered (0.22 µm) seawater from the appropriate test areas, to avoid ‘recovery’ of the polychaetes. Preliminary trials showed that this operation did not affect seawater pH, initial pO2, temperature or salinity. Before determination of O2 uptake, here used as a proxy for metabolic rate ( ) (as in [63–65]), individuals were left for 1 h in the incubation chamber to allow recovery from handling in order to minimize behavioural disturbances, which may affect their physiological responses [66]. For further details on metabolic rate determination, see appendix 2 in the electronic supplementary material.

) (as in [63–65]), individuals were left for 1 h in the incubation chamber to allow recovery from handling in order to minimize behavioural disturbances, which may affect their physiological responses [66]. For further details on metabolic rate determination, see appendix 2 in the electronic supplementary material.

At the end of the experiment, polychaetes were bagged, placed in a cool box and returned to the laboratory. Here, they were gently blotted to remove excess seawater, before being weighed using a high precision balance (AT 200, Mettler-Toledo Ltd). To maintain environmental seawater chemistry and temperature stable during measurements, seawater was continuously pumped (BE-M 30, Rover Pompe, Polverara, Italy) directly from the exposure site into a large water bath (volume = 64 l) and the overflow drained. To ensure maximum thermal and pH stability, as well as comparability to the exposure sites, a fast flow rate (approx. 85 l min−1) was employed, thereby allowing us to relate metabolic rate responses solely to the effect of field acclimatization to elevated pCO2/low pH. As an extra measure, during the experimental trials, seawater samples were collected at regular intervals from the exposure sites by snorkelling or diving, and from the water bath, to verify that pH, salinity and temperature were relatively stable and comparable. Polychaetes were never directly exposed to high flow rate, avoiding any mechanical damage or disturbance.

(h). Statistical analysis of the physiological data

As a two-way orthogonal experimental design was employed, separately for both transplant experiments, the effect of exposure to elevated pCO2/low pH on  of the species examined was tested using general linear models (GLMs), with ‘exposure’ (in situ incubation to low and elevated pCO2) and ‘species’ as fix factors, and using wet body mass as a covariate, in combination with the EMM test with Bonferroni correction. Preliminary analyses showed that the term station had no significant effect on polychaete

of the species examined was tested using general linear models (GLMs), with ‘exposure’ (in situ incubation to low and elevated pCO2) and ‘species’ as fix factors, and using wet body mass as a covariate, in combination with the EMM test with Bonferroni correction. Preliminary analyses showed that the term station had no significant effect on polychaete  (p > 0.05), and so this term was removed from subsequent analyses.

(p > 0.05), and so this term was removed from subsequent analyses.

To investigate the response of populations of tolerant species collected from both inside and outside the CO2 vents, a further two-way orthogonal experimental design was employed, separately for each species (A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii), including the site of collection (collection from low and elevated pCO2 site) or ‘origin’, and the site of in situ incubation (to low and elevated pCO2) or ‘exposure’ as factors, using GLMs, with ‘wet body mass’ as covariate, in combination with the EMM test with Bonferroni correction.

data for transplant experiments met assumptions of normality of distribution following log10 transformation (max. Z92 = 1.109, p = 0.280, Kolmogorov–Smirnov's test). Assumptions of homogeneity of variance were also met following log10 transformations for the data from experiment 1 (F11,84 = 1.904, p = 0.05, Bartlett's test), whereas assumptions were not met following transformations for data from experiment 2 (minimum F5,66 = 4.446, p < 0.001). However, as our experimental design included a minimum of four treatments per experiment with approximately 11 replicates per treatment, we assumed that the ANOVA design employed should be tolerant to deviation from the assumption of heteroscedasticity [67,68]. However, we also tested the residuals from each analysis against the factor tested, and no significant relationships were detected (p > 0.05). Post-hoc analyses were conducted using the EMM test with α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 19.

data for transplant experiments met assumptions of normality of distribution following log10 transformation (max. Z92 = 1.109, p = 0.280, Kolmogorov–Smirnov's test). Assumptions of homogeneity of variance were also met following log10 transformations for the data from experiment 1 (F11,84 = 1.904, p = 0.05, Bartlett's test), whereas assumptions were not met following transformations for data from experiment 2 (minimum F5,66 = 4.446, p < 0.001). However, as our experimental design included a minimum of four treatments per experiment with approximately 11 replicates per treatment, we assumed that the ANOVA design employed should be tolerant to deviation from the assumption of heteroscedasticity [67,68]. However, we also tested the residuals from each analysis against the factor tested, and no significant relationships were detected (p > 0.05). Post-hoc analyses were conducted using the EMM test with α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 19.

(i). Sequence generation

For A. mediterranea, DNA was extracted from each individual using the DNEasy tissue kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's instructions. For P. dumerilii, DNA was extracted using the hotshot method of Montero-Pau et al. [69].

Two gene regions were amplified for both species using polymerase chain reaction (PCR): the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI, 658–710 bp) and the nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS, alignment of 495 bp). PCRs were performed in 20–25 µl volume using standard chemistry and standard cycles. Some samples of A. mediterranea were amplified for COI using a primer cocktail originally designed for fish as described in Ivanova et al. [70], whereas other A. mediterranea and all P. dumerilii were amplified using the universal primers by Folmer et al. [71] or specifically designed primers. All primers are listed in the electronic supplementary material, table A1.2 of appendix 1.

PCR products were visualized following gel electrophoresis in ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels and cleaned with ExoSap-IT (Affymetrix) QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or with the Illustra GFX PCR DNA purification kit, or purification was carried out by Macrogen Europe before sequencing. For A. mediterranea, cycle sequencing was conducted on 10 µl volumes with the BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 chemistry. Sequence reactions were cleaned with BigDye XTerminator. Sequences were analysed with an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer and edited in Sequencher 4.8 (Genecodes). For P. dumerilii, sequences were generated at Macrogen Europe and edited with Codon Code Aligner. All sequences were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KC591782–KC591950 (see the electronic supplementary material, table A1.3 in appendix 1).

(j). Sequence analyses

COI sequences were aligned in BioEdit [72] using the ClustalW algorithm. ITS sequences were aligned in the software Muscle as implemented in MEGA 5 [67]. The final alignments had the following lengths: P. dumerilii, COI: 568 bp; A. mediterranea, COI: 658 bp; P. dumerilii, ITS: 608 bp; A. mediterranea, ITS: 498. The COI alignments included selected outgroups as available in GenBank. These were used to root the trees. No outgroups were used in the analyses of ITS, because no closely related sequences were available in GenBank. The ITS trees are unrooted.

All tree reconstructions were performed in MEGA v. 5.0 [73] using maximum likelihood as the optimality criterion under a general time reversible model with gamma distribution of substitution rates (five discrete steps) and a proportion of invariable sites (GTR + I + G model). Branch support was calculated by performing 1000 bootstrap replicates. Trees were edited in FigTree v. 1.3.1 [74].

3. Results

No mortality was observed for any of the test species during collection, transplant or experimentation. All polychaetes appeared in good health, actively moving when transferred from the transplantation chamber to the incubation chambers, and in semi-transparent species food traces were visible in the digestive system.

(a).

data are presented in the electronic supplementary material, appendix 3, and data on body mass and number of specimens tested for each treatment are reported in the electronic supplementary material, appendix 4. In summary, mean

data are presented in the electronic supplementary material, appendix 3, and data on body mass and number of specimens tested for each treatment are reported in the electronic supplementary material, appendix 4. In summary, mean  varied among species, ranging from (mean ± s.e.) −0.082 ± 0.083 log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP in S. spallanzani collected under control conditions and exposed to control conditions, and 1.632 ± 0.056 log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP in S. prolifera collected inside the vents and exposed to control conditions (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 3).

varied among species, ranging from (mean ± s.e.) −0.082 ± 0.083 log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP in S. spallanzani collected under control conditions and exposed to control conditions, and 1.632 ± 0.056 log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP in S. prolifera collected inside the vents and exposed to control conditions (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 3).

(b).  responses of all species collected in low pCO2 areas

responses of all species collected in low pCO2 areas

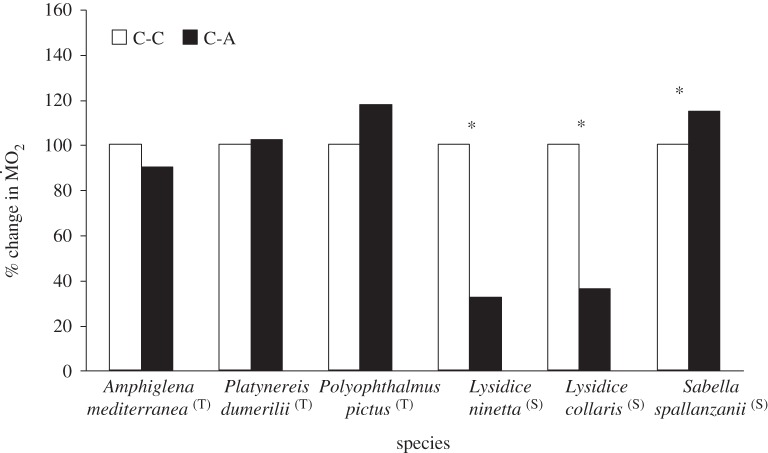

The polychaete species collected from low pCO2 areas differed from each other in the way their mean  responded to exposure to elevated pCO2 conditions (figure 2), as indicated by the presence of a significant interaction between the terms species and exposure (F5,95 = 5.611; p < 0.0001). The three sensitive species showed significant differences in their

responded to exposure to elevated pCO2 conditions (figure 2), as indicated by the presence of a significant interaction between the terms species and exposure (F5,95 = 5.611; p < 0.0001). The three sensitive species showed significant differences in their  under elevated pCO2 conditions (p < 0.05);

under elevated pCO2 conditions (p < 0.05);  increased significantly in S. spallanzanii, and decreased significantly in L. collaris and L. ninetta. The three tolerant species (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and P. pictus), on the other hand, showed no significant difference in mean

increased significantly in S. spallanzanii, and decreased significantly in L. collaris and L. ninetta. The three tolerant species (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and P. pictus), on the other hand, showed no significant difference in mean  when exposed to elevated pCO2 conditions (p > 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean

when exposed to elevated pCO2 conditions (p > 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean  (F1,95 = 1.149; p = 0.287).

(F1,95 = 1.149; p = 0.287).

Figure 2.

Percentage change of metabolic rates ( ) of non-calcifying marine ‘tolerant’ (T) (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and P. pictus) and ‘sensitive’ (S) (L. collaris, L. ninetta and S. spallanzanii) polychaete species collected from low pCO2/elevated pH conditions outside the vents and exposed to (i) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (C-C), and (ii) elevated pCO2 conditions within the vents (C-A). Mean

) of non-calcifying marine ‘tolerant’ (T) (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and P. pictus) and ‘sensitive’ (S) (L. collaris, L. ninetta and S. spallanzanii) polychaete species collected from low pCO2/elevated pH conditions outside the vents and exposed to (i) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (C-C), and (ii) elevated pCO2 conditions within the vents (C-A). Mean  (expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP) measured under control conditions was set as 100% and mean

(expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP) measured under control conditions was set as 100% and mean  measured under acidified conditions recalculated accordingly. Asterisk (*) indicates the presence of a significant difference between the mean

measured under acidified conditions recalculated accordingly. Asterisk (*) indicates the presence of a significant difference between the mean  measured under control conditions (C) and acidified conditions (A), according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.05).

measured under control conditions (C) and acidified conditions (A), according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.05).

(c).  responses of tolerant species collected in elevated pCO2 areas

responses of tolerant species collected in elevated pCO2 areas

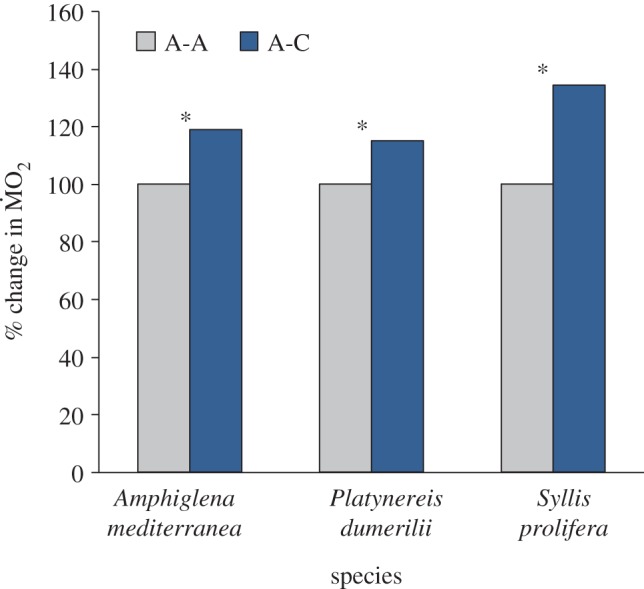

Tolerant species collected from the elevated pCO2 areas did not differ significantly from each other in the way mean  responded to exposure to low pCO2 conditions (figure 3), as indicated by the fact that the interaction term ‘species’ × ‘exposure’ in our analysis was not significant (F2,71 = 1.635; p = 0.203). In fact, all three tolerant species tested (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and S. prolifera) showed a significant increase in mean

responded to exposure to low pCO2 conditions (figure 3), as indicated by the fact that the interaction term ‘species’ × ‘exposure’ in our analysis was not significant (F2,71 = 1.635; p = 0.203). In fact, all three tolerant species tested (A. mediterranea, P. dumerilii and S. prolifera) showed a significant increase in mean  when exposed to low pCO2 conditions (p < 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean

when exposed to low pCO2 conditions (p < 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean  (F1,71 = 3.545; p = 0.064).

(F1,71 = 3.545; p = 0.064).

Figure 3.

Percentage change of  of non-calcifying ‘tolerant’ marine polychaete species collected from elevated pCO2/low pH conditions within the vents and exposed to (i) elevated pCO2 conditions inside the vents (A-A) and (ii) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (A-C). Mean

of non-calcifying ‘tolerant’ marine polychaete species collected from elevated pCO2/low pH conditions within the vents and exposed to (i) elevated pCO2 conditions inside the vents (A-A) and (ii) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (A-C). Mean  (expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP) measured under acidified conditions was set as 100% and mean

(expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP) measured under acidified conditions was set as 100% and mean  measured under control conditions recalculated accordingly. Asterisk (*) indicates the presence of a significant difference between the mean

measured under control conditions recalculated accordingly. Asterisk (*) indicates the presence of a significant difference between the mean  measured under acidified conditions (A) and control conditions (C), according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.05). (Online version in colour.)

measured under acidified conditions (A) and control conditions (C), according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.05). (Online version in colour.)

(d).  responses of tolerant species from elevated and low pCO2 areas

responses of tolerant species from elevated and low pCO2 areas

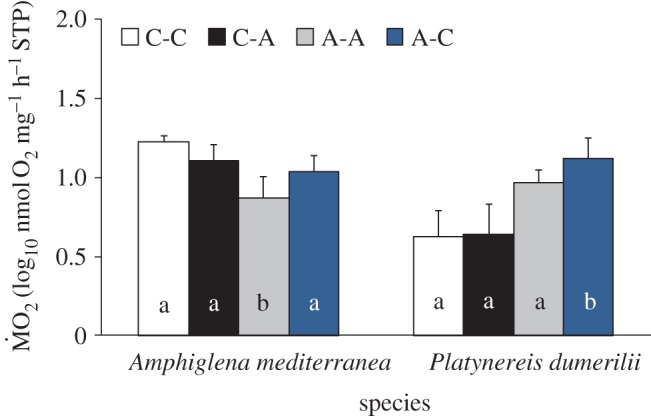

Individuals of A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii from both control and elevated pCO2 areas showed different  responses to exposure to low and elevated pCO2 conditions (figure 4), as indicated by the presence of a significant three-way interaction between the terms ‘species’, ‘origin’ and ‘exposure’ (F1,91 = 5.828; p = 0.018). A. mediterranea collected from acidified areas and re-transplanted into acidified areas showed a significantly lower mean

responses to exposure to low and elevated pCO2 conditions (figure 4), as indicated by the presence of a significant three-way interaction between the terms ‘species’, ‘origin’ and ‘exposure’ (F1,91 = 5.828; p = 0.018). A. mediterranea collected from acidified areas and re-transplanted into acidified areas showed a significantly lower mean  when compared with all other treatments (p < 0.05), while all other comparisons were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). By contrast, individuals of P. dumerilii collected in acidified areas and exposed to low pCO2 conditions showed a significantly greater

when compared with all other treatments (p < 0.05), while all other comparisons were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). By contrast, individuals of P. dumerilii collected in acidified areas and exposed to low pCO2 conditions showed a significantly greater  when compared with all other treatments (p < 0.05), while not showing any significant difference in mean

when compared with all other treatments (p < 0.05), while not showing any significant difference in mean  among each other (p > 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean

among each other (p > 0.05). Finally, wet body mass had no significant effect on mean  (F1,71 = 3.545; p = 0.064).

(F1,71 = 3.545; p = 0.064).

Figure 4.

Effect of exposure to different pCO2 conditions on the mean  of the tolerant species A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii collected from either low pCO2/elevated pH conditions outside the vents and exposed to (i) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (C-C) and (ii) elevated pCO2 conditions within the vents (C-A) or collected from elevated pCO2/low pH conditions within the vents and exposed to (iii) elevated pCO2 conditions inside the vents (A-A) and (iv) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (A-C). Mean

of the tolerant species A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii collected from either low pCO2/elevated pH conditions outside the vents and exposed to (i) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (C-C) and (ii) elevated pCO2 conditions within the vents (C-A) or collected from elevated pCO2/low pH conditions within the vents and exposed to (iii) elevated pCO2 conditions inside the vents (A-A) and (iv) low pCO2 conditions outside the vents (A-C). Mean  is expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP. Histograms present mean values ± s.e. Significantly different treatments, separately for each species, are indicated by different lower case letters inside the column (according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction, p ≤ 0.05). (Online version in colour.)

is expressed as log10 nmol O2 mg−1 h−1 STP. Histograms present mean values ± s.e. Significantly different treatments, separately for each species, are indicated by different lower case letters inside the column (according to the EMM test with Bonferroni correction, p ≤ 0.05). (Online version in colour.)

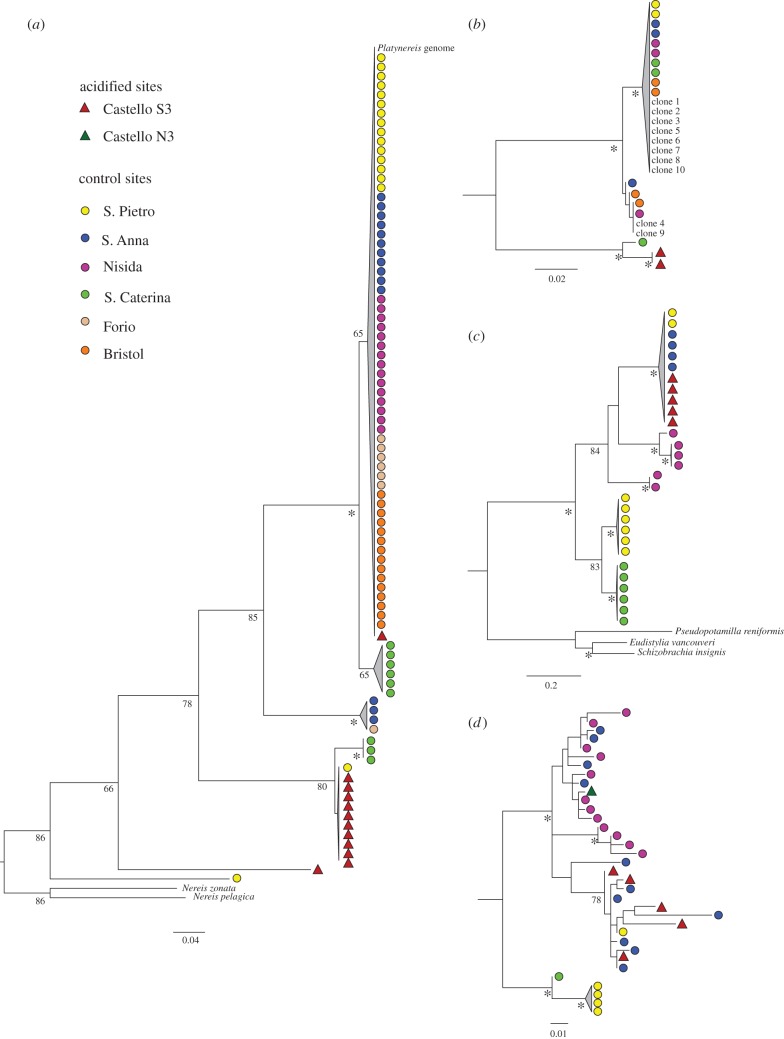

(e). Phylogenetic analyses

For both P. dumerilii and A. mediterranea, the phylogenetic trees generated distinguish multiple distinct evolutionary lineages, with low genetic diversity within them (figure 5). The COI tree for P. dumerilii shows that one of these genetic lineages (figure 5a) contains 10 of the 12 sequenced individuals from the acidified site and a single individual from a nearby control site. One individual from the acidified site falls into a clade consisting of individuals from control sites. Another individual forms its own genetic lineage. In the ITS tree (figure 5b), the two individuals from the acidified site form a genetic lineage distinct from all other populations.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic trees resulting from maximum-likelihood analysis of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) and ITS sequence data. Branch support is indicated as bootstrap percentages (1000 pseudoreplicates); asterisk (*) indicates bootstrap value greater than 98%. (a) COI tree for P. dumerilii. Genbank accession numbers for outgroups: Nereis zonata: HQ024403; Nereis pelagica: GU672554; (b) ITS tree for P. dumerilii. The designations ‘clone 1’ to ‘clone 10’ with their respective GenBank accession numbers refer to [75]; (c) COI tree for Amphiglena mediterranea. GenBank accession numbers for outgroups: Pseudopotamilla reniformis: GU672463; Eudistylia vancouveri: HM473371; Schizobrachia insignis: HM473778. (d) ITS tree for A. mediterranea. (Online version in colour.)

In contrast to P. dumerilii, the COI tree for A. mediterranea reveals that all individuals from the acidified site fall into the same clade with individuals from nearby control sites (figure 5c). Likewise, the ITS tree for A. mediterranea also does not show genetic separation between acidified and non-acidified sites (figure 5d).

4. Discussion and conclusions

Here, we show that a marine metazoan (P. dumerilii) is able to physiologically adapt to chronically elevated levels of pCO2. However, such adaptation is not ubiquitous among all tolerant species found in the CO2 vents, even when their ecologies are similar. The physiological plasticity to chronically elevated pCO2 shown by A. mediterranea also appears to be a viable strategy for the successful colonization of elevated pCO2 environments. Finally, sensitive species, when exposed acutely to elevated pCO2 conditions, exhibit either considerable up or downregulation of their metabolism. In what follows we discuss species metabolic response to elevated pCO2 in relation to (i) the current distribution and abundance patterns of different species around the CO2 vents, (ii) extinctions that occurred during past climate change events, and (iii) species' alternative pathways of physiological resilience to ongoing ocean acidification.

(a). Discriminating between acclimatization and adaptation

The effect of pCO2 on metabolic rate differs consistently between sensitive and tolerant polychaete species, but for tolerant taxa the response patterns observed may have been achieved either via acclimatization or adaptation. In fact, organisms may be able to adjust their physiology, via phenotypic plasticity (acclimatization), e.g. during ontogeny in direct developers such as A. mediterranea (see [29]), or via the selection of genotypes associated with phenotypes best able to cope with conditions found within the CO2 vents, as in P. dumerilii (see [76]). However, which strategy is adopted (i.e. acclimatization or adaptation) has different genetic, ecological and conservation implications. Therefore, to make predictions on how marine life will respond to future ocean acidification, it is important to discriminate between the strategies.

Here, we show that individuals of A. mediterranea living inside the CO2 vents appear to be acclimatized, but not adapted, to elevated pCO2. This is because once removed from elevated pCO2 (and probably under hypoxaemia [77,78]) their metabolic rates return to a ‘normal’ status: i.e. comparable with that of individuals from low pCO2 areas. Alternatively, individuals of P. dumerilii living inside the CO2 vents appear physiologically adapted to elevated pCO2. When removed from the vents their metabolic rate is approximately 44% more elevated when compared with vent individuals kept inside the vents. The metabolism of vent specimens is thus constantly maintained at high levels, presumably to compensate for (although only in part) the chronic pCO2-induced hypoxaemia they are probably subjected to [77,78].

Previous studies show that unicellular organisms can adapt to elevated pCO2 [79–81]. Our study provides evidence that a marine ectotherm (P. dumerilii) has been able to genetically and physiologically adapt to chronic and elevated levels of pCO2, and supports those studies that have indicated the potential of marine metazoans to adapt to elevated pCO2 [76,82–87]. Furthermore, this adaptation may have occurred over a relatively short geological time. In fact, based on archaeological and historical evidences, the CO2 vent system off Ischia is estimated to be 1850 years old [62].

Although metabolic phenotypic plasticity may be the first ‘mechanism’ of response to preserve positive function levels when exposed to environmental disturbance [28], it often comes at a cost [88,89]. Plastic responses can be accompanied by the reallocation of the available energy budget away from growth and reproduction [30], cf. [90,91]. When the cost becomes too high, the selection of phenotypes better able to cope with elevated pCO2 conditions should be favoured as this is a less ‘expensive’ strategy [76]. Local adaptation leads to the improvement of population physiological performances, thus reducing energy costs of regulation and maintenance, improving an organism's ability to persist locally. However, if adaptation occurs at the expense of genetic diversity, this could lead to a decrease in the performance for other traits (e.g. life-history traits). When evolutionary trade-offs are less costly than phenotypic plastic reshuffling, adaptation should be favoured.

The multiple genetic lineages observed in P. dumerilii and A. mediterranea suggest that both actually represent complexes of cryptic species, a common phenomenon in polychaetes [92–97]. In our case, the geographical distribution of these lineages provides additional support for our findings on physiological adaptation and acclimatization from the transplant experiments. Having pelagic larval stages [98], P. dumerilii might be expected to display a high degree of genetic homogeneity on small geographical scales. However, our molecular analyses show a high degree of genetic differentiation among populations at and near the vents (figure 5a,b). This corroborates the idea that the strain of P. dumerilii sampled in the CO2 vent is indeed physiologically (and genetically) adapted to low pCO2. Nonetheless, COI analysis indicates that some (but limited) exchange of individuals between the acidified sites and nearby control takes place, as one individual from the low pCO2 area was found at the vent sites, and one individual with the genetic make-up of the vent population was found in the control sites. Whether these individuals actually thrive and reproduce in the presumably less suitable habitats remains to be thoroughly examined. Nonetheless, based on our current (limited) evidence, one may infer that some form of ecological competitive exclusion may occur between the two strains.

The average genetic distance between the vent strain and its sister group, consisting of three individuals from Santa Caterina, is 3.8%. Coincidentally, this divergence was chosen by Carr et al. [99] to separate molecular operational taxonomic units in polychaetes on the basis of being 10 times greater than intracluster divergence. Estimates of mutation rates in annelids vary tremendously, ranging from 0.2% Myr−1 [100] to 7% Myr−1 [94]. Even with a high mutation rate of 7%, the separation of the vent clade from its sister group would date to 542 000 years ago, not compatible with an origin at the same time as the appearance of the island of Ischia, dated approximately 150 kyr [101]. If the emergence of the island of Ischia is used as a calibration point, the resulting mutation rate for P. dumerilii would be 12–13% per million years, which is approximately 10 times higher than in most invertebrate taxa [75,102]. Alternatively, we can hypothesize that the ‘vent strain’ of P. dumerilii was already established elsewhere before the vents and the island formed, given the volcanic nature of the whole Gulf of Naples. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of rapid evolution. The distinctiveness of our vent populations makes it unlikely that mating with nearby populations occurs, allowing genetic drift in this population. It is also likely that bottlenecks may have occurred in this population, when the vent was first inhabited by a few individuals, supporting the notion of rapid evolution. Such rapid adaptation along an environmental gradient has been shown to occur on a very fine scale in Trinidadian guppies [103,104]. To resolve the questions of the age of the clade, data from multiple loci and a credible calibration point are required.

On the other hand, in A. mediterranea, both the COI and ITS analyses indicate that the vent-inhabiting population is genetically indistinguishable from the nearby control populations. The lack of a strong population structure suggests that local adaptation to the vents may not have taken place in this species, as one would have expected based on the fact that A. mediterranea is a brooder [105], and thus more likely to be subjected to the selection pressure of exposure to elevated pCO2 during its entire life cycle, from early developmental stages to senescence: see, for example, selective swipes [106,107]. The absence of a distinct ‘vent strain’ in A. mediterranea supports the notion that the ability to colonize areas with elevated pCO2 is a result of acclimatization and not adaptation. This suggests that ‘phenotypic buffering’ sensu [108] in some cases may be as good a strategy as adaptation to prevent taxa extinction in the face of elevated pCO2 conditions.

(b). Metabolic responses in CO2-tolerant and CO2-sensitive species from control areas

We demonstrated that tolerant species, when collected from control areas, maintain their pre-exposure metabolic rate levels during acute exposure to elevated pCO2, thus supporting our initial prediction for these species (type 2 acclimatization/adaptation sensu [46]), at least based on the acclimatization regime used here. Our results could be analogous to those of Maas et al. [11], who showed that four pteropod species naturally migrating into semi-permanent elevated pCO2/low pO2 areas were able to maintain their metabolic rate when exposed to elevated pCO2.

By contrast, the species of polychaetes not found in the CO2 vents were unable to maintain the same metabolic rate and displayed either significant upregulation (S. spallanzani, +15%—type 3 acclimatization/adaptation sensu [46]) or significant downregulation (Lysidice spp., approx. −66%—type 1 acclimatization/adaptation sensu [46]) of their metabolic rates during acute exposure. Comparably, Maas et al. [11] found that the pteropod Diacria quadridentata (Blainville, 1821), which does not migrate into semi-permanent elevated pCO2/low pO2 areas, responded to the exposure to elevated pCO2 by reducing its metabolic rates by approx. 50%. Overall, Maas et al.'s study [11], together with this present investigation, suggest that the chemical environment species are acclimatized to in situ may influence their resilience to ocean acidification. Our study goes further by supporting the idea that physiological adaptation and phenotypic buffering enable taxa to colonize and persist in chronically elevated pCO2 environments.

(c). The link to past extinctions and future resilience

The physiological ability to preserve metabolic rates to pre-exposure levels while experiencing hypercapnia may be key to species survival in the initial phase of colonization of naturally elevated pCO2 areas. Thus, our study supports the idea that taxa possessing well-developed regulatory and homeostasis abilities are most likely to be best able to face future ocean acidification conditions [8,34,36,109,110]. However, the ability to cope with chronic exposure to elevated pCO2 conditions appears to be characterized by the acquisition of moderately lower metabolic rates (on average −23% in this study) in both the acclimatized and the adapted species. While metabolic depression in the short term helps an organism to maintain a balance between energy supply and demand [15,16,25,26,111], in the longer term it can involve the reorganization of its energy budget, often leading to a decrease in its scope for growth and reproduction [2].

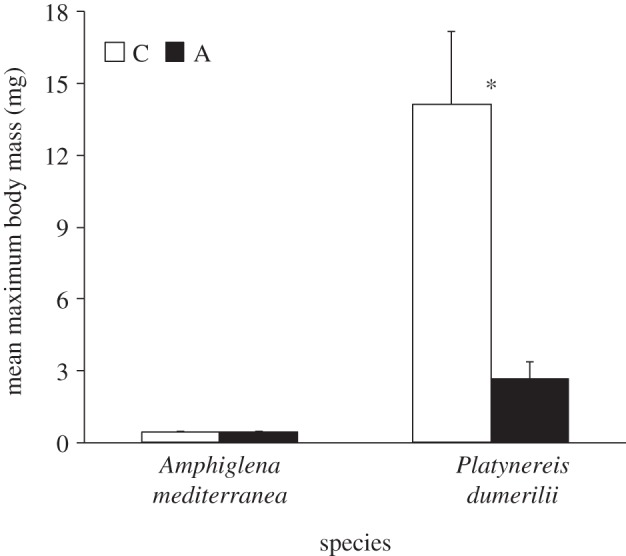

We suggest that in the face of elevated pCO2 conditions, such as those experienced, for example, during the Permo-Triassic boundary [112–115], the evolution (or development) of moderate metabolic depression may have enabled some marine organisms to persist locally and globally. This may have come, however, at the cost of some life-history traits, such as reduced body size: see [116] for a review on the Lilliput Effect. Consistent with this idea, the mean body size of the adult individuals of P. dumerilii collected from the CO2 vents was approximately 80% lower when compared with that of adult individuals from the non-acidified areas (figure 6; F1,46 = 14.547; p < 0.0001). By contrast, A. mediterranea shows no change in body mass (figure 6; F1,46 = 0.016; p = 0.900), against our prediction that acclimatization may come at some cost. In our study, we did not carry out a systematic collection of polychaetes living around the CO2 vents, our data requiring further validation; nonetheless, our sampling is the outcome of the haphazard selection of the larger adult individuals we could find. Thus, our measure represents an estimate for the ‘mean maximum body size’ that individuals of P. dumerilii and A. mediterranea reach when chronically exposed to conditions found inside or outside the CO2 vents, including different pCO2 levels, altered algal composition and habitat complexity among others [45,117]. Nevertheless, differences in body size patterns observed between A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii could be explained by the fact that the strain of P. dumerilii from the CO2 vents shows overall a higher mean metabolic rate when compared with those of the non-acidified strain. This may suggest an increase in the costs for maintenance and repair in this species, costs that A. mediterranea may not incur. As size in several polychaete species defines the maximum number of eggs that a female can produce, it will be important to verify whether individuals from the vent strain could have a reduced reproductive output when compared with individuals from the low pCO2 strain.

Figure 6.

Effect of exposure to different pCO2 conditions on the mean maximum body mass of the tolerant species A. mediterranea and P. dumerilii collected from either low pCO2/elevated pH conditions outside the vents or elevated pCO2 conditions within the vents Histograms present mean values ± s.e. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between the mean maximum body mass measured under acidified conditions (A) and control conditions (C), according to a GLM test.

On the other hand, an extreme increase in metabolism (i.e. S. spallanzani) or extreme forms of depression (i.e. L. collaris and L. ninetta) appear not to support life inside the CO2 vents. Thus, past mass extinctions may have stemmed from the inability of some species to maintain their metabolic rate within strict limits and thus their energy budgets. Ultimately, the ability of marine organisms to persist in a rapidly changing ocean [118–120] is largely dependent on the taxa's ability for rapid physiological adaption, which could potentially occur, via genetic assimilation of emerging phenotypes [28,103,108,121,122]. However, in the assemblage of polychaetes examined here, phenotypic buffering appears also to be a viable strategy to avoid local extinction. Thus, it appears that both plasticity and adaptation may be key to prevent species' risk for extinction in the face of ongoing ocean acidification [118], and thus largely determine the fate of marine biodiversity. Nonetheless even within tolerant groups such as the Polychaeta, some species appear sensitive to elevated pCO2 and at risk of extinction, as they are unable to cope with ocean acidification [43,45,123–125]. Species extinction will cause shifts in community structure and functions, which may ultimately drive important changes in ecosystem functioning [125,126].

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Haslam, M. Hawkins and the staff of the Benthic Ecology research unit (Villa Dorhn, Ischia) for advice and technical support. We particularly thank Captain V. Rando for his outstanding support with all boat operations and for building the S. spallanzani transplant chambers. We thank E. Borda for assistance with molecular methods and primer design for Amphiglena mediterranea. We are grateful to N.M. Whiteley for the loan of the Oxysense system. We thank C. Ghalambor, F. Melzner, J. Havenhand and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive and useful criticisms on early drafts of this manuscript.

Data accessibility

All data are archived with the British Oceanographic Data Centre, http://www.bodc.ac.uk.

Funding statement

This work was undertaken while P.C. was a recipient of a Research Council UK Research Fellowship to investigate ocean acidification at Plymouth University. J.I.S. was a recipient of RCUK research fund. This project was supported by an ASSEMBLE Grant to P.C. and S.P.S.R, the UKOA NERC grant NE/H017127/1 awarded to J.I.S. and P.C. [Task 1.4 ‘Identify the potential for organism resistance and adaptation to prolonged CO2 exposure’ of the NERC Consortium Grant ‘Impacts of ocean acidification on key benthic ecosystems, communities, habitats, species and life cycles’], ENEA internal funding to C.L. and SZN internal funding to M.C.G. The molecular work undertaken on P. dumerilii was supported in part by an ASSEMBLE Grant to J.D.H. The molecular work conducted on A. mediterranea at TAMUG was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DEB 1036186 to A.S.).

References

- 1.Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West GB. 2004. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85, 1771–1789 (doi:10.1890/03-9000) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibly RM, Calow P. 1986. Physiological ecology of animals: an evolutionary approach. Hong Kong, China: Blackwell Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calow P, Forbes VE. 1998. How do physiological responses to stress translate into ecological and evolutionary processes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 120A, 11–16 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spicer JI, Gaston KJ. 1999. Physiological diversity and its ecological implications. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaston KJ. 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kooijman SALM. 2010. Dynamic energy budget theory for metabolic organisation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozinovic F, Calosi P, Spicer JI. 2011. Physiological correlates of geographical range in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 155–179 (doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145055) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melzner F, Gutowska M, Langebuch M, Dupont S, Lucassen M, Thorndyke M, Bleich M, Pörtner H-O. 2009. Physiological basis for high CO2 tolerance in marine ectothermic animals: pre-adaptation through lifestyle and ontogeny? Biogeosciences 6, 2313–2331 (doi:10.5194/bg-6-2313-2009) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendriks IE, Duarte CM, Álvarez M. 2010. Vulnerability of marine biodiversity to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 86, 157–164 (doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2009.11.022) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroeker KJ, Kordas RL, Crim RN, Singh GG. 2010. Meta-analysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1419–1434 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01518.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maas AE, Wishner KF, Seibel BA. 2012. The metabolic response of pteropods to acidification reflects natural CO2-exposure in oxygen minimum zones. Biogeosciences 9, 747–757 (doi:10.5194/bg-9-747-2012) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melatunan S. 2012. ‘Biochemical, metabolic and morphological responses of the intertidal gastropod Littorina littorea to ocean acidification and increased temperature’, p. 222 PhD thesis, Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reipschläger A, Pörtner H-O. 1996. Metabolic depression during environmental stress: the role of extracelullar versus intracellular pH in Sipunculus nudus. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 1801–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaelidis B, Ouzounis C, Paleras A, Pörtner H-O. 2005. Effects of long-term moderate hypercapnia on acid–base balance and growth rate in marine mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 293, 109–118 (doi:10.3354/meps293109) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosa R, Seibel BA. 2008. Synergistic effects of climate-related variables suggest future physiological impairment in a top oceanic predator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20 776–20 780 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0806886105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melatunan S, Calosi P, Rundle SD, Moody JA, Widdicombe S. 2011. Exposure to elevated temperature and pCO2 reduces respiration rate and energy status in the periwinkle Littorina littorea. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 583–594 (doi:10.1086/662680) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura M, Ohki S, Suzuki A, Sakai K. 2011. Coral larvae under ocean acidification: Survival, metabolism, and metamorphosis. PLoS ONE 6, e14521 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014521) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood HL, Spicer JI, Widdicombe S. 2008. Ocean acidification may increase calcification rates, but at a cost. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 1767–1773 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0343) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood HL, Spicer JI, Lowe DM, Widdicombe S. 2010. Interaction of ocean acidification and temperature; the high cost of survival in the brittlestar Ophiura ophiura. Mar. Biol. 157, 2001–2013 (doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1469-6) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beniash E, Ivanina A, Lieb NS, Kurochkin I, Sokolova IM. 2010. Elevated level of carbon dioxide affects metabolism and shell formation in oysters Crassostrea virginica. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 419, 95–108 (doi:10.3354/meps08841) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutowska MA, Pörtner H-O, Melzner F. 2008. Growth and calcification in the cephalopod Sepia officinalis under elevated seawater pCO2. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 303–309 (doi:10.3354/meps07782) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchant HK, Calosi P, Spicer JI. 2010. Short-term exposure to hypercapnia does not compromise feeding, acid–base balance or respiration of Patella vulgata but surprisingly is accompanied by radula damage. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 90, 1379–1384 (doi:10.1017/S0025315410000457) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomsen J, Melzner F. 2010. Moderate seawater acidification does not elicit long-term metabolic depression in the blue mussel Mytilus edulis. Mar. Biol. 157, 2667–2676 (doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1527-0) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donohue P, Calosi P, Bates A, Laverock AH, Rastrick SPS, Mark FC, Stroble A, Widdicombe S. 2012. Physiological and behavioural impacts of exposure to elevated pCO2 on an important ecosystem engineer, the burrowing shrimp Upogebia deltaura. Aquat. Biol. 15, 73–86 (doi:10.3354/ab00408) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop T, Brand MD. 2000. Processes contributing to metabolic depression in hepatopancreas cells from the snail Helix aspersa. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3603–3612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seibel BA, Walsh PJ. 2003. Biological impacts of deep-sea carbon dioxide injection inferred from indices of physiological performance. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 641–650 (doi:10.1242/jeb.00141) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guppy M, Withers P. 1999. Metabolic depression in animals: physiological perspectives and biochemical generalizations. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 74, 1–40 (doi:10.1017/S0006323198005258) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghalambor CK, McKay JK, Carroll SP, Reznick DN. 2007. Adaptive versus non-adaptive phenotypic plasticity and the potential for contemporary adaptation in new environments. Funct. Ecol. 21, 394–407 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01283.x) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller GM, Watson S-A, Donelson JM, McCormick MI, Munday PL. 2012. Parental environment mediates impacts of increased carbon dioxide on a coral reef fish. Nature Clim. Change 2, 858–861 (doi:10.1038/nclimate1599) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pörtner H-O. 2008. Ecosystem effects of ocean acidification in times of ocean warming: a physiologist's view. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 203–217 (doi:10.3354/meps07768) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Findlay HS, Wood HL, Kendall MA, Spicer JI, Twitchett RJ, Widdicombe S. 2011. Comparing the impact of high CO2 on calcium carbonate structures in different marine organisms. Mar. Biol. Res. 7, 565–575 (doi:10.1080/17451000.2010.547200) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melatunan S, Calosi P, Rundle SD, Widdicombe S, Moody JA. 2013. The effects of ocean acidification and elevated temperature on shell plasticity and its energetic basis in an intertidal gastropod. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 472, 155–168 (doi:10.3354/meps10046) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dove PM, De Yoreo JJ, Weiner S. 2006. Biomineralization Reviews in mineralogy and geochemistry, vol. 54 (ed. Rosso JJ.). Washington, DC: Mineralogical Society of America [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pane EF, Barry JP. 2007. Extracellular acid–base regulation during short-term hypercapnia is effective in a shallow-water crab, but ineffective in a deep-sea crab. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 334, 1–9 (doi:10.3354/meps334001) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munday PL, Crawley NE, Nilsson GE. 2009. Interacting effects of elevated temperature and ocean acidification on the aerobic performance of coral reef fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 388, 235–242 (doi:10.3354/meps08137) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calosi P, Rastrick SPS, Graziano M, Thomas SC, Baggini C, Carter HA, Hall-Spencer JM, Milazzo M, Spicer JI. In press Ecophysiology of sea urchins living near shallow water CO2 vents: investigations of acid–base balance and ionic regulation using in-situ transplantation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. (doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.11.040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Comeau S, Edmunds PJ, Spindel NB, Carpenter RC. 2013. The responses of eight coral reef calcifiers to increasing partial pressure of CO2 do not exhibit a tipping point. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 388–398 (doi:10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0388) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrne M, Lamare M, Winter D, Dworjanyn SA, Uthicke S. 2013. The stunting effect of a high CO2 ocean on calcification and development in sea urchin larvae, a synthesis from the tropics to the poles. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20120439 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0439) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widdicombe S, Needham HR. 2007. Impact of CO2-induced seawater acidification on the burrowing activity of Nereis virens and sediment nutrient flux. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 341, 111–122 (doi:10.3354/meps341111) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane A, Mukherjee J, Chan VS, Thiyagarajan V. In press Decreased pH does not alter metamorphosis but compromises juvenile calcification of the tube worm Hydroides elegans. Mar. Biol. (doi:10.1007/s00227-012-2056-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Godbold JA, Solan M. 2013. Long-term effects of warming and ocean acidification are modified by seasonal variation in species responses and environmental conditions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130186 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall-Spencer JM, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Martin S, Ransome E, Fine M, Turner SM, Rowley SJ, Tedesco D, Buia M-C. 2008. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature 454, 96–99 (doi:10.1038/nature07051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cigliano M, Gambi MC, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Patti FP, Hall-Spencer JM. 2010. Effects of ocean acidification on invertebrate settlement at natural volcanic CO2 vents. Mar. Biol. 157, 2489–2502 (doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1513-6) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroeker KJ, Micheli F, Gambi MC. 2013. Ocean acidification causes ecosystem shifts via altered competitive interactions. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 156–159 (doi:10.1038/nclimate1680) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroeker KJ, Micheli F, Gambi MC, Martz TR. 2011. Divergent ecosystem responses within a benthic marine community to ocean acidification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14 515–14 520 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1107789108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Precht H. 1958. Concepts of the temperature adaptation of unchanging reaction systems of cold-blooded animals. In Physiological adaptation (ed. Prossser CL.), pp. 50–78 Washington, DC: American Physiological Society [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gambi MC, Lorenti M, Russo GF, Scipione MB, Zupo V. 1992. Depth and seasonal distribution of some groups of the vagile fauna of Posidonia oceanica leaf stratum: structural and feeding guild analyses. Mar. Ecol. 13, 17–39 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.1992.tb00337.x) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giangrande A, Delos AL, Fraschetti S, Musco L, Licciano M, Terlizzi A. 2003. Polychaete assemblages along a rocky shore on the South Adriatic coast (Mediterranean Sea): patterns of spatial distribution. Mar. Biol. 143, 1109–1116 (doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1162-0) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giangrande A, Fraschetti S, Terlizzi A. 2002. Local recruitment differences in Platynereis dumerilii (Polychaeta, Nereididae) and their consequences for population structure. Ital. J. Zool. 69, 133–139 (doi:10.1080/11250000209356450) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gambi MC. 2002. Spatio-temporal distribution and ecological role of polychaete borers of Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile scales. Bull. Mar. Sci. 71, 1323–1331 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gambi MC, Cafiero G. 2001. Functional diversity in the Posidonia oceanica ecosystem: an example with polychaete borers of the scales. In Mediterranean ecosystems: structure and processes (eds Faranda FM, Guglielmo L, Spezie G.), pp. 399–405 Milano, Italy: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bocchetti R, Fattorini D, Gambi MC, Regoli F. 2004. Trace metal concentrations and susceptibility to oxidative stress in the polychaete Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin) (Sabellidae): potential role of antioxidants in revealing stressful environmental conditions in the Mediterranean. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 46, 353–361 (doi:10.1007/s00244-003-2300-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giangrande A, Licciano M, Pagliara P, Gambi MC. 2000. Gametogenesis and larval development in Sabella spallanzanii (Polychaeta: Sabellidae) from the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Biol. 136, 847–861 (doi:10.1007/s002279900251) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alsop DH, Wood CM. 1997. The interactive effects of feeding and exercise on oxygen consumption, swimming performance and protein usage in juvenile rainbow trout. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 2337–2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCue MD. 2006. Specific dynamic action: a century of investigation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 144A, 381–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pierrot D, Lewis E, Wallace DWR. 2006. MS Excel program developed for CO2 system calculations, ORNL/CDIAC-105. Oak Ridge, TN: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehrbach C, Culberson CH, Hawley JE, Pytkowicz RM. 1973. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 18, 897–907 (doi:10.4319/lo.1973.18.6.0897) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dickson AG, Millero FJ. 1987. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep-Sea Res. 34, 1733–1743 (doi:10.1016/0198-0149(87)90021-5) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dickson AG. 1990. Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Deep-Sea Res. 37, 755–766 (doi:10.1016/0198-0149(90)90004-F) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Lombardi C, Cocito S, Hall-Spencer JM, Gambi MC. 2010. Effects of ocean acidification and high temperatures on the bryozoan Myriapora truncata at natural CO2 vents. Mar. Ecol. 31, 447–456 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00354.x) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodolfo-Metalpa R, et al. 2011. Coral and mollusc resistance to ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 308–312 (doi:10.1038/nclimate1200) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lombardi C, Gambi MC, Vasapollo C, Taylor AC, Cocito S. 2011. Skeletal alterations and polymorphism in a Mediterranean bryozoan at natural CO2 vents. Zoomorphology 130, 135–145 (doi:10.1007/s00435-011-0127-y) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spicer JI, Eriksson SP. 2003. Does the development of respiratory regulation always accompany the transition from pelagic larvae to benthic fossorial postlarvae in the Norway lobster Nephrops norvegicus (L.)? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 295, 219–243 (doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(03)00296-X) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calosi P, Morritt D, Chelazzi G, Ugolini A. 2007. Physiological capacity and environmental tolerance in two sandhopper species with contrasting geographical ranges: Talitrus saltator and Talorchestia ugolinii. Mar. Biol. 151, 1647–1655 (doi:10.1007/s00227-006-0582-z) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rastrick SPS, Whiteley NM. 2011. Congeneric amphipods show differing abilities to maintain metabolic rates with latitude. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 154–165 (doi:10.1086/658857) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kamenos NA, Calosi P, Moore PG. 2006. Substratum-mediated heart rate responses of an invertebrate to predation threat. Anim. Behav. 71, 809–813 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.05.026) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sokal R, Rohlf FJ. 1995. Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. New York, NY: Freeman and Company [Google Scholar]

- 68.Underwood AJ. 1997. Experiments in ecology: their logical design and interpretation using analysis of variance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montero-Pau J, Gómez A, Muñoz J. 2008. Application of an inexpensive and high-throughput genomic DNA extraction method for the molecular ecology of zooplanktonic diapausing eggs. Limnol. Oceanogr. Meth. 6, 218–222 (doi:10.4319/lom.2008.6.218) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ivanova NV, Zemlak TS, Hanner RH, Hebert PDN. 2007. Universal primer cocktails for fish DNA barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 544–548 (doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01748.x) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Folmer O, Black M, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. 1994. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]