Abstract

The actin cytoskeleton is the major force-generating machinery in the cell, which can produce pushing, pulling, and resistance forces. To accomplish these diverse functions, actin filaments, with help of numerous accessory proteins, form higher order ensembles, networks and bundles, adapted to specific tasks. Moreover, dynamic properties of the actin cytoskeleton allow a cell to constantly build, renew, and redesign actin structures according to its changing needs. High resolution architecture of actin filament arrays provides key information for understanding mechanisms of force generation. To generate pushing force, cells use coordinated polymerization of multiple actin filaments organized into branched (dendritic) networks or parallel bundles. This review summarizes our current knowledge of the structural organization of these two actin filament arrays.

Introduction

Coordinated polymerization of multiple interconnected actin filaments is key strategy for generating pushing force by the actin cytoskeleton. Acting as a cohort, actin filaments can achieve necessary stiffness to produce large forces. These forces are typically applied to the plasma membrane or membrane-enclosed organelles in order to change their shape or induce motility. Mechanistic understanding of any complex machinery greatly benefits from structural information. Determining the actin cytoskeleton structure, however, is challenging, because actin filaments are too tightly packed in the cell to be adequately resolved by light microscopy. Although new techniques such as subdiffraction fluorescence microscopy and atomic-force microscopy may overcome this barrier in future, most information about actin cytoskeleton structure has been obtained using different types of electron microscopy (EM).

Traditional thin section EM of plastic-embedded samples has been instrumental for characterizing relatively stable structures, such as actin filament bundles. However, dynamic actin filaments are not adequately preserved by this technique and their structure was revealed using whole-mount cell preparations contrasted by negative [1] or positive [2] staining or by metal shadowing [3,4]. More recently, cryo EM that analyzes ice-embedded samples in order to minimize preparation artifacts, in combination with electron tomography, began to contribute to structural studies of the actin cytoskeleton [5]. However, an extremely low contrast of cryo EM samples and their sensitivity to irradiation limits utility of the method and requires extensive image processing, which frequently produces unnaturally looking images of actin filaments with ambiguous gaps and fusions. Despite technical limitations of individual EM approaches, together they can provide an informative picture of the actin cytoskeletal architecture.

Dendritic Networks

A molecular mechanism of pushing force generation by dendritic networks is described by the dendritic nucleation model [6]. According to this model (Figure 1A), branched actin filaments are produced by the Arp2/3 complex, which upon activation by nucleation-promoting factors nucleates a new actin filament off the side of a pre-existing (“mother”) filament at 70° angle and structurally maintains the resulting branch junction. The specific architecture and dynamic properties of the dendritic network are controlled by additional proteins that promote (Ena/VASP proteins and formins) or block (capping proteins) elongation of actin filaments, regulate branch stability (cortactin, coronin, GMF), and cross-link (α-actinin, filamin) or disassemble (ADF/cofilin) the actin network. The dendritic nucleation mechanism is best studied in lamellipodia, flat protrusions at the leading edge of migrating cells, but the Arp2/3 complex and its partners also participate in many other cellular activities, such as various types of endocytosis, motility and biogenesis of intracellular organelles, and formation of diverse cell-cell junctions, suggesting that branched networks are present in these other locations (Figure 2).

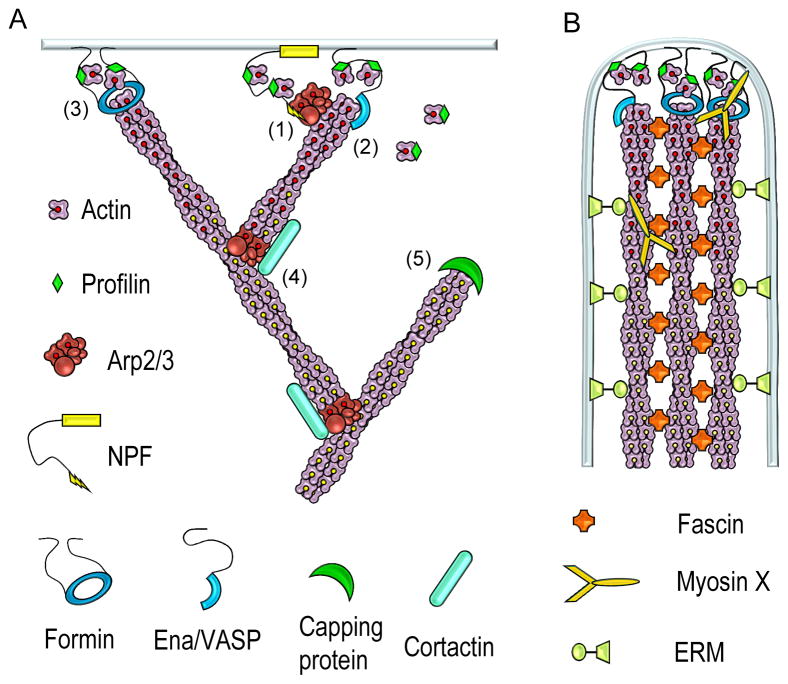

Figure 1. Molecular architecture of protrusive actin filament arrays.

(A) Dendritic networks in lamellipodia. (1) The Arp2/3 complex is coactivated at the plasma membrane by binding both a nucleation promoting factor (NPF) and a mother filament; (2,3) elongation of the newly nucleated branch, as well as of the mother filament, is transiently assisted by Ena/VASP (2) and/or formin (3) family proteins, which protect barbed ends from capping, recruit actin-profilin complexes, and mediate processive attachment of barbed ends to the plasma membrane. (4) During plasma membrane advance or retrograde flow, the Arp2/3 complex-containing actin filament branch becomes a part of the dendritic network and can be stabilized by cortactin. (5) After a period of elongation, some barbed ends lose elongation factors and become capped by capping protein; this process balances continuous nucleation of new filaments and is a part of filament length control in the dendritic network. Disassembly of the network is mediated by severing activity of ADF/cofilin and dissociation of branches (not depicted).

(B) Parallel bundles in filopodia. Long actin filaments in the bundle are oriented with their barbed ends to the plasma membrane at the tip of the filopodium. Their elongation is assisted by formins and Ena/VASP proteins, as well as myosin X. Filaments are bundled by fascin and laterally attached to the plasma membrane by ERM proteins.

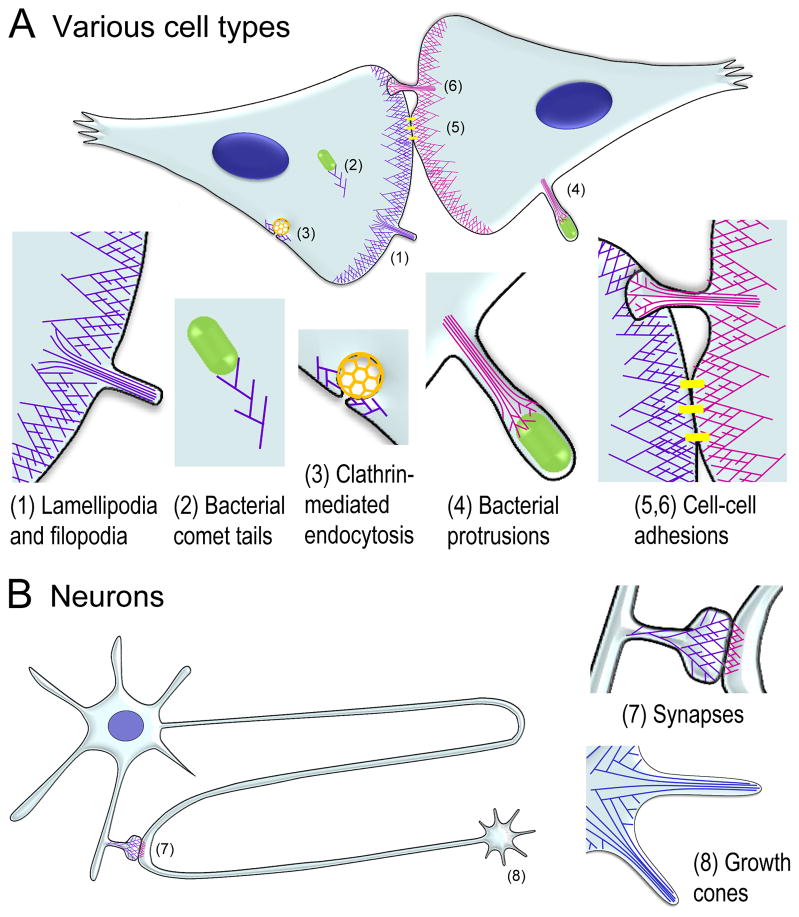

Figure 2. Functions of protrusive actin filament arrays.

(A) Many cell types, such as fibroblasts, epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells employ dendritic networks and parallel bundle for different purposes. (1) Dendritic networks and parallel bundles at the leading edge drive membrane protrusion. (2) Dendritic networks induced by bacterial pathogens propel these bacteria throughout the bulk cytoplasm of a host cell; this motility is thought to mimic a normal membrane trafficking process. (3) During clathrin-mediated endocytosis, dendritic networks associate with clathrin-coated structures to promote their invagination, constriction and departure. (4) When bacterial comet tails become enclosed within a filopodium-like protrusion, the dendritic actin network appears to reorganize into a parallel bundle, although the continuing presence of a branched network at the actin-bacterium interface is a speculation at present. (5, lower part) Lamellipodial dendritic networks in contacting cells press against each other to bring their membranes into close proximity and facilitate cell-cell adhesion during adherens junction formation. (6, upper part) Retraction of an attached lamellipodium transforms its dendritic network into a parallel bundle in a base-to-tip direction, so that a mini-lamellipodium transiently remains at the tip of the bridge; the bundle subsequently recruits myosin II to exert tension on the forming adhesion and thus enhance its strength.

(B) Neurons use protrusive actin arrays for similar purposes, but within neuron-specific strucutres. (7) Dendritic networks are present asymmetrically on both sides of an excitatory synapse, in the dendritic spine (left) and axonal presynaptic terminal (right), where they likely facilitate membrane juxtaposition; despite its narrow elongated shape, the spine neck also contains branched network. (8) Parallel bundles in filopodia are dominant protrusive structures in neuronal growth cones mediating elongation of axons and dendrites; however, dendritic networks are also present between growth cone filopodia and participate in filopodia initiation.

Lamellipodia

Branched actin filaments were discovered in lamellipodia of migrating cells by metal shadowing EM and their significance for pushing force generation was suggested [7]. Subsequent studies with purified proteins, cytoplasmic extracts, and live cells revealed key molecules and events involved in actin-based protrusion. However, despite vast amount of diverse data supporting the dendritic nucleation model, the structural evidence for the existence of branched actin filaments in lamellipodia provided by metal shadowing EM [7,8] was repeatedly challenged by Victor Small and colleagues based on their inability to detect branches by negative staining EM [9,10]. Only recently this issue has been finally settled, when we detected branched actin filaments in their published electron tomograms of negatively stained lamellipodia [11**]. Therefore, the branched architecture of the lamellipodial actin network is currently confirmed by two independent EM techniques, although it unfortunately took more than ten years to come to a consensus on this point.

The specific geometry of a dendritic network in lamellipodia, such as density, length and orientation of filaments and frequency and distribution of branches, can vary depending on cell type and conditions, although these correlations have not been specifically addressed. Network geometry can be controlled, endogenously or experimentally, by absolute and relative rates of actin filament nucleation, elongation, and capping. For example, downregulation of capping protein [12–14] or upregulation of elongation factors, formin mDia2 [15] or VASP [16], increase actin filament lengths in branched networks. Conversely, interference with mDia2 [15] or Ena/VASP activities [16] produces very short branched actin filaments in lamellipodia. Dendritic network architecture also correlates with the protrusive behavior. It appears that when actin filament elongation dominates over branching, lamellipodia protrude faster, but they are less robust and frequently switch to ruffling or transform into filopodia [12,16,17]. Endogenous regulation of actin nucleation, elongation, and capping can be used by the cell to adjust the network architecture to its specific needs. For example, nascent lamellipodia formed shortly after a release from serum starvation [8] or at the edge of an intracellular wound [18], appear to contain a greater density of branches and shorter individual filaments compared with established lamellipodia undergoing steady state protrusion. The density of branches can also vary locally within the same lamellipodium (Figure 2). For example, when the lamellipodial dendritic network begins to reorganize into filopodial bundles, the density of branches locally decreases, while the filament length increases [19]. Accordingly, in neuronal growth cones where filopodia are abundant, branched network is seen only in small areas between filopodia [20]. Conversely, fish or frog epidermal keratocytes that lack filopodia display relatively uniform distribution of branches along the leading edge [7,8,18].

The Arp2/3 complex not only nucleates actin filaments at the plasma membrane, but also acts as an end-to-side cross-linker. Therefore, the Arp2/3 complex and actin branches are present throughout the lamellipodium with a peak at the leading edge and a gradual decline toward the rear [8]. The slope of the decline may be controlled by relative rates of actin nucleation, debranching, and depolymerization and likely varies among systems. Thus, Vinzenz et al. found that actin branches were evenly distributed throughout the lamellipodium, or only slightly enriched at the front [18]. Although authors interpreted this profile as a lack of dependence between force generation and branching, this interpretation seems weak, because it remains unclear whether and how the front-to-rear distribution of branches affects protrusive behavior of lamellipodia. Also, since Vinzenz et al. selected for EM analysis thinner regions of lamellipodia that are more suitable for tomographic tracking, their data may not represent the entire range of lamellipodial architectures. Technical problems, such as a loss of very short filaments at the lamellipodial edge during drying of negatively stained samples or blotting of cryo samples, are also not excluded.

Actin filament orientation determines the direction of pushing force and therefore is another important parameter of dendritic networks. Although repeating nucleation of actin branches at 70° angle should eventually reverse the force direction, most actin filaments in lamellipodia remain oriented with their growing “barbed” ends roughly forward. This phenomenon can be explained by several non-exclusive mechanisms, such as targeting of Arp2/3 complex activators to the plasma membrane, preferential capping of backward-facing barbed ends [21,22], biased binding of the Arp2/3 complex to the convex surface of mother filaments deformed by membrane resistance [23*], and selective elimination of mechanically “unfit” filaments [24]. More subtle differences in the actin filament orientation in lamellipodia may correlate with the speed of protrusion. Thus, actin filaments in lamellipodia of fast moving keratocytes displayed a bimodal distribution of orientation with preferred angles of ±35° relative to the direction of movement [21], whereas slower moving keratocytes had most filaments oriented roughly orthogonal to the leading edge [25]. In contrast, pausing lamellipodia of macrophages display many tangentially oriented filaments [26]. However, tangential filaments were also dominant in protruding lamellipodia of migrating dendritic cells [27]. It remains unclear whether these filaments contribute to the pushing force or play a different role.

Membrane Organelles

The Arp2/3 complex and other components of the dendritic nucleation machinery function in trafficking and/or morphogenesis of membrane organelles [28]. However, structure of the organelle-associated actin cytoskeleton is mostly unknown except for actin patches during clathrin-mediated endocytosis and for bacterial comet tails, which are thought to represent an exaggerated version of endosomal trafficking machinery hijacked by pathogens.

Some intracellular pathogens, such as Listeria monocytogenes and Shigella flexneri, assemble Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin-rich comet tails to propel themselves throughout the cytosplasm [29]. Although the structure of prototypical endosome-associated dendritic networks is not yet available, architecture of bacterial comet tails has been determined in several conditions. Comet tails formed in vitro in cytoplasmic extracts contained branched actin filaments throughout the tail [30]. Similarly, in the bulk cytoplasm of infected cells, comet tails of Listeria or Shigella contained non-oriented short actin filaments [31,32], likely corresponding to the dendritic network. However, when moving Listeria induced filopodium-like protrusions from the plasma membrane, their comet tails contained many long axial actin filaments [33], suggesting that the dendritic network undergoes dramatic remodeling within the membrane-confined space (Figure 2A). Since the filopodial tip marker, myosin X [34], is recruited to Listeria or Shigella specifically when they induce surface protrusions [35*], this remodeling may be governed by the convergent elongation mechanism functioning during formation of leading edge filopodia [19], or it may follow an alternative pathway, like that acting during initiation of cell-cell adhesions in endothelial cells [36*].

During clathrin-mediated endocytosis in yeast and mammals, small Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin patches assemble at endocytic sites and facilitate endocytic vesicle formation. As revealed by metal shadowing EM [37*], endocytic actin patches in mammalian cells consist of very short and densely branched actin filaments, suggesting relatively high rates of nucleation and capping. Importantly, actin barbed ends have been found to face the neck of the clathrin-coated pit, and thus presumably push at this site (Figure 2A). This finding resolved an uncertainty regarding a mode of force application during clathrin-mediated endocytosis [38], at least for mammalian cells. In yeast, however, the situation remains controversial, because existing EM approaches cannot resolve individual actin filaments. Thin section EM of actin patches combined with either immunogold labelling [39*] or correlative fluorescence imaging [40*] revealed that actin assembly was either subsequent to or coincident with plasma membrane invagination, which suggests different geometries of actin networks. The former result is consistent with force applied to the tip of the invagination [39*], whereas in the latter case, the actin network can press against the plasma membrane and undergo retrograde flow simultaneously pulling the attached endocytic bud into the cytoplasm [40*]. Future studies should resolve this ambiguity.

Since the Arp2/3 complex is activated by a nucleation-promoting factor in conjunction with a pre-existing actin filament, the source of the first mother filament at the onset of the dendritic nucleation cycle remained an open question. EM analyses of endocytic actin patches in mammalian cells [37*] or nascent lamellipodia at the edge of a healing intracellular wound [18] suggested that a random actin filament present in the vicinity of the Arp2/3 complex activation site can serve as a mother filament. In yeast, where cytoplasmic actin filaments are scarce, it was proposed that actin fragments severed away from a disassembling actin patch by cofilin can serve as mother filaments to initiate a new patch [41].

Cell-Cell Junctions

The Arp2/3 complex functions in various cell-cell junctions, such as adherens junctions in epithelial and endothelial cells [42], in neuronal [43,44] and immune [45] synapses, and prefusion junctions in myoblasts [46]. Among them, dendritic actin networks have been ultrastructurally characterized in excitatory neuronal synapses [47*,48*] and at initial stages of adherens junction formation in endothelial cells [36*].

Excitatory synapses in neurons are formed between presynaptic terminals on axons and postsynaptic dendritic spines, actin-rich protrusions on dendrites frequently having mushroom-like shape. As revealed by metal shadowing EM of cultured hippocampal neurons, bulbous heads of dendritic spines, which are involved in synapse formation, are filled with a dense three-dimensional branched actin network immunopositive for typical components of dendritic nucleation machinery, such as the Arp2/3 complex and capping protein [48*]. Electron tomography of thin-sectioned brain samples [47*] also showed a dense fibrillar meshwork in dendritic spines. Although tracing individual filaments was rather difficult, this technique revealed that actin meshwork density was maximal immediately adjacent to the postsynaptic density, the signalling platform of dendritic spines, and that sites of actin-membrane interactions contained electron-dense material, possibly, corresponding to barbed end-associated elongation factors, such as VASP [49]. Unexpectedly, presynaptic sites in cultured hippocampal neurons were also found to contain a branched actin network, albeit less elaborate than in dendritic spines [48*]. The two networks, presynaptic and postsynaptic, are in close proximity at the junction site marked by the presence of N-cadherin, suggesting that these networks press against each other to promote junctional interaction of plasma membranes (Figure 2B). It is likely that Arp2/3 complex-dependent networks play a similar role in other cell-cell junctions.

Adherens junctions are essential for compartmentalization of tissues by epithelial and endothelial sheets. Cell-cell interaction is mediated by cadherins and other adhesion molecules, which can form continuous lines or discrete puncta, and stabilized by the actin cytoskeleton [42]. Ultrastructurally, adherens junctions appear associated mostly with actin bundles, whereas light microscopy approaches revealed contribution of dynamic Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin structures [42]. Metal shadowing EM was recently used to define actin organization during adherens junction initiation in endothelial cells [36*]. It showed that the first contact between cells is made by lamellipodia containing typical dendritic actin networks (Figure 2A). Similar to neuronal synapses [48*], networks of two adjacent cells can press against each other to bring membranes in close proximity and thus facilitate engagement of adhesion molecules. The lamellipodial interaction is followed by cell edge retraction, which leaves behind filopodia-like bridges connected by punctate adherens junctions, which then transform into contractile stress fibers [36*]. This reorganization, probably, strengthens adherens junctions through tension-dependent mechanisms [50,51*]. Although filopodial bridges and conventional filopodia at the leading edge of migrating cells are both formed by reorganization of dendritic networks, the mechanisms of reorganization are quite different. Instead of forming from tip to base, like leading edge filopodia [19], filopodial bridges propagate in the opposite direction and transiently retain mini-lamellipodia at their tips during this process [36*] (Figure 2A).

Parallel Bundles

Formation of tight bundles of uniformly oriented and synchronously polymerizing actin filaments is another major strategy for generating pushing force by the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 1B). This mechanism is best understood for leading edge filopodia of migrating cells [52,53]. Similar bundles are also present in other cylindrical cell surface extensions, such as brush border microvilli in intestinal epithelium and hair cell stereocilia in the inner ear. Unlike filopodia, microvilli and stereocilia maintain a constant length and exhibit very slow (microvilli) [54] or negligible (stereocilia) dynamics [55]. Notably, not all cylindrical membrane protrusions contain parallel actin bundles. For example, narrow elongated necks of dendritic spines (Figure 2), as well as dendritic filopodia, the precursors of dendritic spines, contain branched actin networks and differently oriented actin filaments [48*].

Leading edge filopodia are needle-like membrane protrusions functioning in cell motility and navigation (Figure 2A). Actin filaments within the filopodial bundle undergo treadmilling, whereby subunits are added to barbed ends at the plasma membrane, move away from the tip as a part of the filament lattice, and are released at the rear. Uninterrupted and fast elongation of individual actin filaments in the bundle is assisted by barbed-end associated proteins of formin and Ena/VASP families. Elongation-promoting activities of these otherwise unrelated protein families include protection of barbed ends from capping, recruitment of profilin-actin complexes to increase local concentration of polymerizable subunits, and processive attachment of elongating barbed ends to the membrane to increase efficiency of pushing [56]. Unconventional myosin X also promotes filopodium elongation, probably, by delivering actin monomers or pushing the membrane away from barbed ends for easier monomer addition [34,35*]. All these proteins are enriched at filopodial tips and likely reside in the structurally recognizable filopodial tip complex [19]. As a cohesive multimolecular scaffold, the tip complex may also synchronize polymerization of filopodial filaments.

Bundling of actin filaments increases their collective stiffness and allows them to overcome membrane resistance and avoid buckling during protrusion. The major actin filament cross-linker in leading edge filopodia is fascin [57,58], a bivalent monomeric protein, whose actin-binding sites have been only recently characterized [59*,60*,61]. Although fascin forms stiff and stable bundles in filopodia, it undergoes fast turnover within bundles [58,62], which may result from its ability to switch between active and inactive conformations [61]. Fascin-mediated bundling changes the twist of actin filaments [63], which may affect binding of other proteins to actin filaments, such as cofilin [64,65] and myosin X [66,67].

In contrast to overall consensus regarding the actin filament organization and dynamics in established filopodia, the origin of filopodial filaments remains a matter of debate [53]. Two types of actin filament nucleators, the Arp2/3 complex and formins, participate in filopodial protrusion. Whereas the role of the Arp2/3 complex in this process is best explained by its nucleating activity, it remains unclear whether formins promote filopodia by nucleating new filaments or by elongating the pre-existing ones. Since cells that are completely or largely devoid of the Arp2/3 complex still make filopodia [68*,69*], formins or other actin nucleators may indeed generate filopodial actin filaments [15,70]. High resolution structural analysis correlated with de novo filopodia formation is required to understand the mechanism of filopodia initiation in these systems.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Small JV, Isenberg G, Celis JE. Polarity of actin at the leading edge of cultured cells. Nature. 1978;272:638–639. doi: 10.1038/272638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schliwa M, van Blerkom J. Structural interaction of cytoskeletal components. J Cell Biol. 1981;90:222–235. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.1.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heuser JE, Kirschner MW. Filament organization revealed in platinum replicas of freeze-dried cytoskeletons. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:212–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svitkina TM, Shevelev AA, Bershadsky AD, Gelfand VI. Cytoskeleton of mouse embryo fibroblasts. Electron microscopy of platinum replicas. Eur J Cell Biol. 1984;34:64–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Harush K, Maimon T, Patla I, Villa E, Medalia O. Visualizing cellular processes at the molecular level by cryo-electron tomography. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:7–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svitkina TM, Verkhovsky AB, McQuade KM, Borisy GG. Analysis of the actin-myosin II system in fish epidermal keratocytes: mechanism of cell body translocation. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:397–415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1009–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban E, Jacob S, Nemethova M, Resch GP, Small JV. Electron tomography reveals unbranched networks of actin filaments in lamellipodia. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:429–435. doi: 10.1038/ncb2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Small JV. Dicing with dogma: de-branching the lamellipodium. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Yang C, Svitkina T. Visualizing branched actin filaments in lamellipodia by electron tomography. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1012–1013. doi: 10.1038/ncb2321. author reply 1013–1014. This article presents independent evaluation of EM data published by Urban et al. (Ref. 17) and reports that Urban et al. overlooked multiple actin branches in their data and therefore their main conclusion that lamellipodia contain unbranched actin filaments is incorrect. In their reply, Small et al. have admitted their mistake. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mejillano MR, Kojima S, Applewhite DA, Gertler FB, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Lamellipodial versus filopodial mode of the actin nanomachinery; pivotal role of the filament barbed end. Cell. 2004;118:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantaloni D, Boujemaa R, Didry D, Gounon P, Carlier MF. The Arp2/3 complex branches filament barbed ends: functional antagonism with capping proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:385–391. doi: 10.1038/35017011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vignjevic D, Yarar D, Welch MD, Peloquin J, Svitkina T, Borisy GG. Formation of filopodia-like bundles in vitro from a dendritic network. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:951–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Czech L, Gerboth S, Kojima S, Scita G, Svitkina T. Novel roles of formin mDia2 in lamellipodia and filopodia formation in motile cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bear JE, Svitkina TM, Krause M, Schafer DA, Loureiro JJ, Strasser GA, Maly IV, Chaga OY, Cooper JA, Borisy GG, et al. Antagonism between Ena/VASP proteins and actin filament capping regulates fibroblast motility. Cell. 2002;109:509–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Applewhite DA, Barzik M, Kojima S, Svitkina TM, Gertler FB, Borisy GG. Ena/VASP proteins have an anti-capping independent function in filopodia formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2579–2591. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-0990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinzenz M, Nemethova M, Schur F, Mueller J, Narita A, Urban E, Winkler C, Schmeiser C, Koestler SA, Rottner K, et al. Actin branching in the initiation and maintenance of lamellipodia. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2775–2785. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svitkina TM, Bulanova EA, Chaga OY, Vignjevic DM, Kojima S, Vasiliev JM, Borisy GG. Mechanism of filopodia initiation by reorganization of a dendritic network. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:409–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korobova F, Svitkina T. Arp2/3 complex is important for filopodia formation, growth cone motility, and neuritogenesis in neuronal cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1561–1574. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maly IV, Borisy GG. Self-organization of a propulsive actin network as an evolutionary process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181338798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaus TE, Taylor EW, Borisy GG. Self-organization of actin filament orientation in the dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7086–7091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701943104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Risca VI, Wang EB, Chaudhuri O, Chia JJ, Geissler PL, Fletcher DA. Actin filament curvature biases branching direction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2913–2918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114292109. This study reports that the Arp2/3 complex preferentially forms branches on the convex side of the mother filament. This finding links the directionality of actin branching during lamellipodia protrusion to the load-imposed curvature of actin filaments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cardamone L, Laio A, Torre V, Shahapure R, Desimone A. Cytoskeletal actin networks in motile cells are critically self-organized systems synchronized by mechanical interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13978–13983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100549108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weichsel J, Urban E, Small JV, Schwarz US. Reconstructing the orientation distribution of actin filaments in the lamellipodium of migrating keratocytes from electron microscopy tomography data. Cytometry A. 2012;81:496–507. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinnerthaler G, Herzog M, Klappacher M, Kunka H, Small JV. Leading edge movement and ultrastructure in mouse macrophages. J Struct Biol. 1991;106:1–16. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(91)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frittoli E, Matteoli G, Palamidessi A, Mazzini E, Maddaluno L, Disanza A, Yang C, Svitkina T, Rescigno M, Scita G. The signaling adaptor Eps8 is an essential actin capping protein for dendritic cell migration. Immunity. 2011;35:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firat-Karalar EN, Welch MD. New mechanisms and functions of actin nucleation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haglund CM, Welch MD. Host-pathogen interactions: Pathogens and polymers: Microbe-host interactions illuminate the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:7–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron LA, Svitkina TM, Vignjevic D, Theriot JA, Borisy GG. Dendritic organization of actin comet tails. Curr Biol. 2001;11:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gouin E, Gantelet H, Egile C, Lasa I, Ohayon H, Villiers V, Gounon P, Sansonetti PJ, Cossart P. A comparative study of the actin-based motilities of the pathogenic bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and Rickettsia conorii. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1697–1708. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sechi AS, Wehland J, Small JV. The isolated comet tail pseudopodium of Listeria monocytogenes: a tail of two actin filament populations, long and axial and short and random. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerber ML, Cheney RE. Myosin-X: a MyTH-FERM myosin at the tips of filopodia. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3733–3741. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Bishai EA, Sidhu GS, Li W, Dhillon J, Bohil AB, Cheney RE, Hartwig JH, Southwick FS. Myosin-X facilitates Shigella-induced membrane protrusions and cell-to-cell spread. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:353–367. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12051. Myosin X is found to associate with Shigella and Listeria in infected cells specifically when they form protrusions and to function in protrusion elongation, but not initiation. Although metal shadowing EM has been used in the study, no information is provided regarding branched versus bundled actin organization of comet tails in different conditions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Hoelzle MK, Svitkina T. The cytoskeletal mechanisms of cell-cell junction formation in endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:310–323. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0719. The dynamics of cell-cell junction formation and the corresponding architecture of the actin cytoskeleton is determined in cultured endothelial cells by combination of light microscopy and metal shadowing EM. The results show that the initial contact is mediated by protruding lamellipodia. On their retraction, cells maintain contact through filopodia-like bridges, which are formed by a distinct pathway, than conventional filopodia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Collins A, Warrington A, Taylor KA, Svitkina T. Structural organization of the actin cytoskeleton at sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.048. Metal shadowing EM in combination with electron tomography is used to visualize architecture of actin patches associated with clathrin-coated structures. Patches are found to consist of a densely branched actin network, in which actin filament barbed ends are oriented toward the clathrin-coated structure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galletta BJ, Chuang DY, Cooper JA. Distinct roles for Arp2/3 regulators in actin assembly and endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Idrissi FZ, Blasco A, Espinal A, Geli MI. Ultrastructural dynamics of proteins involved in endocytic budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2587–2594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202789109. Thin-section immuno-EM is used to correlate the shape of endocytic invaginations with localization of endocytic proteins in budding yeast. It shows that shallow invaginations are not associated with actin cytoskeleton components. On deep invaginations, actin splits into two populations, at the tip and the plasma membrane, whereas Arp2/3 complex components are detected only at the tip, suggesting that the tip is the site of pushing force application. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Kukulski W, Schorb M, Kaksonen M, Briggs JA. Plasma membrane reshaping during endocytosis is revealed by time-resolved electron tomography. Cell. 2012;150:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.046. Electron tomography of thick sections is correlated with fluorescence microscopy of key endocytic proteins in the same yeast cells. It reveals that clathrin-coated sites lacking actin are invariably flat, while invaginations contain actin markers. The ribosome exclusion zone around endocytic structures, which is interpreted as actin meshwork, surrounds the tip of the invagination and in 70% cases extends to the plasma membrane, where it could exert pressure. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okreglak V, Drubin DG. Loss of Aip1 reveals a role in maintaining the actin monomer pool and an in vivo oligomer assembly pathway. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:769–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michael M, Yap AS. The regulation and functional impact of actin assembly at cadherin cell-cell adhesions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.1012.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Racz B, Weinberg RJ. Microdomains in forebrain spines: an ultrastructural perspective. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8345-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wegner AM, Nebhan CA, Hu L, Majumdar D, Meier KM, Weaver AM, Webb DJ. N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex are critical regulators of actin in the development of dendritic spines and synapses. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15912–15920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801555200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Billadeau DD, Burkhardt JK. Regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics at the immune synapse: new stars join the actin troupe. Traffic. 2006;7:1451–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sens KL, Zhang S, Jin P, Duan R, Zhang G, Luo F, Parachini L, Chen EH. An invasive podosome-like structure promotes fusion pore formation during myoblast fusion. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1013–1027. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Burette AC, Lesperance T, Crum J, Martone M, Volkmann N, Ellisman MH, Weinberg RJ. Electron tomographic analysis of synaptic ultrastructure. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:2697–2711. doi: 10.1002/cne.23067. Electron tomography of semi-thin sections is used to determine structure of neuronal synapses in the rat brain fixed by an osmium-free procedure, which better preserves labile protein structures. A meshwork of thin filaments is found throughout the dendritic spine becoming denser at the periphery of the postsynaptic density. Numerous contacts of filaments with the plasma membrane, contain small accumulations of electron-dense material. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Korobova F, Svitkina T. Molecular architecture of synaptic actin cytoskeleton in hippocampal neurons reveals a mechanism of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:165–176. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0596. Metal shadowing EM of cultured hippocampal neurons reveals branched actin filament networks in heads, necks and bases of dendritic spines, presynaptic boutons and dendritic filopodia, out of which only branch network in the spine head was expected. A small fraction of actin filaments is found to have their barbed end facing the base of the dendritic spine or dendritic filopodium. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin WH, Nebhan CA, Anderson BR, Webb DJ. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) induces actin assembly in dendritic spines to promote their development and potentiate synaptic strength. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36010–36020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huveneers S, Oldenburg J, Spanjaard E, van der Krogt G, Grigoriev I, Akhmanova A, Rehmann H, de Rooij J. Vinculin associates with endothelial VE-cadherin junctions to control force-dependent remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:641–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Liu Z, Tan JL, Cohen DM, Yang MT, Sniadecki NJ, Ruiz SA, Nelson CM, Chen CS. Mechanical tugging force regulates the size of cell-cell junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9944–9949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914547107. A system of microfabricated force sensors is used to demonstrate that adherens junctions in endothelial cells increase or decrease their size in response to increasing or decreasing pulling force, respectively, as it is known for cell-matrix adhesions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mellor H. The role of formins in filopodia formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang C, Svitkina T. Filopodia initiation: Focus on the Arp2/3 complex and formins. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:402–408. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.5.16971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyska MJ, Mooseker MS. MYO1A (brush border myosin I) dynamics in the brush border of LLC-PK1-CL4 cells. Biophys J. 2002;82:1869–1883. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75537-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang DS, Piazza V, Perrin BJ, Rzadzinska AK, Poczatek JC, Wang M, Prosser HM, Ervasti JM, Corey DP, Lechene CP. Multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry reveals slow protein turnover in hair-cell stereocilia. Nature. 2012;481:520–524. doi: 10.1038/nature10745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chesarone MA, Goode BL. Actin nucleation and elongation factors: mechanisms and interplay. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hashimoto Y, Kim DJ, Adams JC. The roles of fascins in health and disease. J Pathol. 2011;224:289–300. doi: 10.1002/path.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vignjevic D, Kojima S, Aratyn Y, Danciu O, Svitkina T, Borisy GG. Role of fascin in filopodial protrusion. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:863–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59*.Jansen S, Collins A, Yang C, Rebowski G, Svitkina T, Dominguez R. Mechanism of actin filament bundling by fascin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30087–30096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251439. This study reports high resolution (2 Å) crystal structure of fascin and localization of two major actin-binding sites to beta-trefoil domains 1 and 3. Residue mutations in both sites impair actin bundle formation in vitro and formation of filopodia in cells. Other fascin mutations suggest existence of secondary actin-binding sites with other actin filaments in the bundle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60*.Sedeh RS, Fedorov AA, Fedorov EV, Ono S, Matsumura F, Almo SC, Bathe M. Structure, evolutionary conservation, and conformational dynamics of Homo sapiens fascin-1, an F-actin crosslinking protein. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:589–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.043. This study reports 2.9 Å resolution crystal structure of fascin-1, which reveals four tandem beta-trefoil domains forming a bi-lobed structure with approximate pseudo 2-fold symmetry. Sequence conservation also suggests putative actin-binding domains of fascin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang S, Huang FK, Huang J, Chen S, Jakoncic J, Leo-Macias A, Diaz-Avalos R, Chen L, Zhang JJ, Huang XY. Molecular mechanism of fascin function in filopodial formation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:274–284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.427971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aratyn YS, Schaus TE, Taylor EW, Borisy GG. Intrinsic dynamic behavior of fascin in filopodia. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3928–3940. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shin H, Purdy Drew KR, Bartles JR, Wong GC, Grason GM. Cooperativity and frustration in protein-mediated parallel actin bundles. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:238102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.238102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Breitsprecher D, Koestler SA, Chizhov I, Nemethova M, Mueller J, Goode BL, Small JV, Rottner K, Faix J. Cofilin cooperates with fascin to disassemble filopodial actin filaments. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3305–3318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schmoller KM, Semmrich C, Bausch AR. Slow down of actin depolymerization by cross-linking molecules. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagy S, Ricca BL, Norstrom MF, Courson DS, Brawley CM, Smithback PA, Rock RS. A myosin motor that selects bundled actin for motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9616–9620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802592105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nagy S, Rock RS. Structured post-IQ domain governs selectivity of myosin X for fascin-actin bundles. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26608–26617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.Wu C, Asokan SB, Berginski ME, Haynes EM, Sharpless NE, Griffith JD, Gomez SM, Bear JE. Arp2/3 is critical for lamellipodia and response to extracellular matrix cues but is dispensable for chemotaxis. Cell. 2012;148:973–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.034. Stable depletion of >98% of the Arp2/3 complex in cultured cells is found to completely inhibit lamellipodia, but preserve filopodia, whereas cell motility in these conditions occurs at lower rates. Metal shadowing EM reveals sparse long actin filaments in the cytoplasm converging into filopodial bundles at the cell periphery. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Suraneni P, Rubinstein B, Unruh JR, Durnin M, Hanein D, Li R. The Arp2/3 complex is required for lamellipodia extension and directional fibroblast cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:239–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112113. Fibroblasts differentiated from embryonic stem cells lacking the Arpc3 subunit of the Arp2/3 complex are found to lack lamellipodia, but produce filopodia, which contain filopodial markers, such as fascin and formins mDia1 and mDia2. Although the instantaneous migration rate of these cells is not different from controls, the migration persistence is decreased. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Block J, Stradal TE, Hanisch J, Geffers R, Kostler SA, Urban E, Small JV, Rottner K, Faix J. Filopodia formation induced by active mDia2/Drf3. J Microsc. 2008;231:506–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]