Abstract

Objectives

Self-rated health (SRH) is an important indicator of overall health, predicting morbidity and mortality. This paper investigates what individuals incorporate into their self-assessments of health and how acculturation plays a part in this assessment. The relationship of acculturation to SRH and whether it moderates the association between indicators of health and SRH is also examined.

Design

The paper is based on data from adults in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, living in the greater Boston area (n=1357) mean age 57.2 (SD=7.6). We used multiple regression analysis and testing for moderation effects.

Results

The strongest predictors of poor self-rated health were the number of existing medical conditions, functional problems, allostatic load and depressive symptoms. Poor self-rated health was also associated with being female, fewer years of education, heavy alcohol use, smoking, poverty, and low emotional support. More acculturated Puerto Rican adults rated their health more positively, which corresponded to better indicators of physical and psychological health. Additionally, acculturation moderated the association between some indicators of morbidity (functional status and depressive symptoms) and self-rated health.

Conclusions

Self-assessments of overall health integrate diverse indicators, including psychological symptoms, functional status and objective health indicators such as chronic conditions and allostatic load. However, adults’ assessments of overall health differed by acculturation, which moderated the association between health indicators and SRH. The data suggest that when in poor health, those less acculturated may understate the severity of their health problems when rating their overall health, thus SRH might thus conceal disparities. Using SRH can have implications for assessing health disparities in this population.

Introduction

The concept of self-rated health

The construct of self- rated health (SRH) has proven to be valuable as an indicator of overall health and as a predictor of morbidity and mortality (Idler and Benyamini, 1997). Though usually assessed by a single item, it has been shown to function as a holistic assessment of one’s overall health, and a strong predictor of future prognosis and risks. A recent conceptual model proposed that SRH lies “at the cross-roads between biology and culture” as it integrates information from multiple sources (Jylhä, 2009). Still, to what extent intuitive (Huisman and Deeg, 2010) and evident bodily sensations relevant to health are taken into account, what other information is integrated, and what is considered as appropriate to report as positive or negative health, may be culturally sensitive. Thus, self-rated health is an intriguing construct, at the intersection of physical, psychological health and cultural meanings of health, illness and expressiveness.

Determinants of SRH

Self-rated health has been studied for the past two decades as a determinant – in particular, as a predictor of mortality—and has been confirmed as a consistent and accurate predictor of mortality in many countries and cultures, even when other health indicators are controlled for (Idler and Benyamini, 1997, Jylhä, 2010, Mackenbach et al., 2002).

A related line of research has studied the determinants of SRH, aiming to identify what goes into these subjective ratings of overall health, and how people reason when making the decision about their rating (Benyamini et al., 1999, Idler et al., 1999). Combinations of quantitative and qualitative approaches have shown the diversity of considerations that people integrate into the rating of their health. It is suggested that “the criteria respondents use in rating their health are complex and multilayered”(Idler et al., 1999), as well as the fact that what they take into account may differ by age and subjective health (Kaplan and Baron-Epel, 2003) and by whether they are in poor or better SRH health (Benyamini et al., 2003).

SRH has been related to clinical or laboratory measures of health. For example positive self-ratings of health were associated with age and gender, with higher HDL-cholesterol concentration (Tomten and Høstmark, 2007). Other markers examined include endocrine measures, including a longitudinal study relating prolactin, cortisol and testosterone to self-rated health (Halford, 2003); and circulating cytokines (Lekander, 2004, Unden et al., 2007). Subjective ratings of poor overall health have also been associated with lower humoral immunity strength (Nakata et al., 2010).

There is evidence that the correspondence of SRH to biomarkers may differ by socioeconomic status. One study reported that SRH was related to biomarkers of metabolic, cardiovascular and immune function and this relationship was modified by educational attainment. For the same subjective rating of health, people with less education had greater biological risk (Dowd and Zajacova, 2010), suggesting that SRH may underestimate inequalities in health.

An association between SRH and allostatic load has been addressed in only a few studies. Allostatic load gives indication of life-time accumulation of physiological dysregulation, through the functioning of several regulatory systems in the body, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the cardiovascular system (CVS), lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism and the immune system (McEwen, 1998). The first study known to us that addresses this question (Chvu, 2008) found an association of higher allostatic load (constructed from 8 biomarkers) and poorer SRH among middle aged women from a number of ethnic groups. Allostatic load (constructed from 11 biomarkers) was shown to predict SRH for both men and women, while other factors contributing to SRH differed by gender (Hampson et al., 2009). An association between poor SRH and high allostatic load, as well as separate biomarkers, was also reported by Hasson et al (2009); the level of biomarkers and which of them related to SRH differed by socioeconomic status (as indicated by education and occupational sector) (Hasson et al., 2009).

Lay meanings of health have been found to be more inclusive and contextual, compared to physician or biomedical definitions of health, and can take into account physical and mental health, as well as functional abilities, social relationships and roles, extent of social activity and spiritual dimensions (Hall et al., 1989, Idler et al., 1999). Singh-Manoux and others tested a total of 35 factors as possible determinants of SRH in two large cross-sectional studies, including groups of factors related to early life experiences, family history, socio-demographic variables, psychosocial factors and health behaviors (in addition to mental and physical health measures) and found that over 80% of the explained variance was due to physical and mental health indicators (Singh-Manoux et al., 2006).

Because the SRH construct is used widely in studies with different ethnicities and nationalities, a longstanding question has been whether differences in self-assessment fully reflect objective (biological, physiological, diagnostic) underlying differences in health, or also reflect cultural differences in meanings of health and its evaluation. Research findings on these questions are mixed. Chandola and Jenkinson (2000) did not find an interaction effect between SRH and ethnicity in any of the models they examined and concluded that the association between SRH and morbidity does not differ across ethnic groups (Chandola and Jenkinson, 2000). Jylhä et al (1998) also found that the way in which SRH was correlated with health and socio-demographic indicators did not differ between adults in Finland and Italy (Jylhä et al., 1998). Others have concluded, though, that differences in SRH, after adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, are likely due to different cultural meanings of health and the way it is assessed (Kómár et al., 2006, Menec et al., 2007, Vuorisalmi et al., 2008). For example Vuorisalmi et al (2008) found a significant interaction effect between country (Sweden or Russia) and chronic diseases in older people, in determining SRH (Vuorisalmi et al., 2008).

Fewer studies have addressed the question of differences in SRH within ethnic and immigrant groups (Abdulrahim and Baker, 2009, Kobayashi et al., 2008); or if the predictive effects of SRH vary according to acculturation. Finch et al (2002) found that SRH was a stronger predictor of mortality after 2 years among more acculturated Latinos than it was among less acculturated ones (Finch et al., 2002). Shetterly et al (1996) found that Latinos were twice as likely as White Americans to report fair/poor health, even when adjusting for health and socioeconomic indicators; and that Latinos who were less acculturated, according to English language use, were more likely to report fair/poor health than more acculturated ones (Shetterly et al., 1996).

Objectives

The Puerto Rican population on the mainland US is an example of an ethnic group with large health disparities when compared to the general population, illustrated through a high burden of physical and psychological illness, social isolation and encounters with discrimination (Tucker et al., 2010). The objective of this paper was to understand the relevance of the SRH construct, its usefulness in work on health disparities for this group, and the implications for studying health disparities generally. Our first question is how do the self-ratings of health made by Puerto Rican adults correspond to objective (biological and diagnostic) indicators of health and disease, measured by allostatic load, its biological components, and existing medical conditions? Further, how do these ratings correspond to self-reported mental health symptoms, and to experiences in the social context, including assessments of problems with activities of daily living, health behaviors, perceived discrimination, perceived social support and engagement in social activities? A second important question is if SRH is associated with acculturation, and does the association between physical, psychological and social wellbeing and SRH differ by level of acculturation?

Methods

Sample

The analyses presented in this paper use data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (Authors). This is a joint study and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (Ethics Committees) of both Universities. The study follows a longitudinal design with a cohort of 1,500 participants at baseline. For this paper we are using cross-sectional baseline data collected between 2004 and 2008.

A total of 2093 individuals were invited to participate, of which 1811 agreed; 1802 were eligible to continue, and baseline data were collected from 1500. At the time of writing of this paper, baseline data were available for n=1357 respondents. Most participants were identified by a two-stage approach, using Census data. First, census tracks containing Puerto Rican adults in the age group were targeted; then, block groups containing Hispanic adults were enumerated door to door. Additional recruitment was done at large Puerto Rican events through random approach, and through media presentations. The criteria for inclusion were that the participants were of self-reported Puerto Rican descent and between the ages of 45–75 years of age at the baseline data collection point. Because blocks were targeted based on density in urban areas, the sample reflects the Puerto Rican community living in these areas, and cannot be generalized to Puerto Ricans living in less Hispanic dense suburban areas. Still, our recruitment strategy gave access to 78% of Puerto Ricans in this age group living in the greater Boston area, and our resulting sample is 15% of all the Puerto Ricans of this age group living in the targeted cities (Authors).

The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. A detailed description of the recruitment process is available elsewhere (Authors) Participants were visited in their homes by bilingual interviewers for data collection, and informed consent was obtained. The data collection included structured interviews lasting between 3 to 4 hours and anthropometric and blood pressure measurements. Interviewers were given instructions for urinary and blood sample collection, which was done on the day following the interview, in their homes. A certified phlebotomist drew blood samples for biochemical analyses, after a 12 hour fast. Overnight, 12-hour, urine samples were also collected.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample, distribution of self-rated health ratings, and differences in self-rated health according to demographic characteristics

| Sample | N and % of sample | SRH1 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n = 1357 | Mean | ||

| Self-rated health (SRH) | 3.67 | ||

| Excellent | 67 (5% ) | ||

| Very good | 79 (5.8%) | ||

| Good | 259 (19.2%) | ||

| Fair | 769 (56.9%) | ||

| Poor | 178 (13.2%) | ||

| Gender | (t) <0.0001 | ||

| Men | 401 (29.6%) | 3.44 | |

| Women | 956 (70.4%) | 3.77 | |

| Age | (F) <0.0001 | ||

| 45–55 | 627 (46.2%) | 3.56 | |

| 56–65 | 497 (36.6%) | 3.76 | |

| 66–75 | 233 (17.2%) | 3.82 | |

| Education | (F) <0.0001 | ||

| No school or <5th | 306 (22.7%) | 3.80 | |

| 5th to 9th | 341 (25.3%) | 3.85 | |

| 9th to 12th | 496 (36.7%) | 3.64 | |

| Some college or Bachelor’s | 181 (13.4%) | 3.34 | |

| Some grad | 26 (1.9%) | 3.08 | |

| Marital Status | (F) <0.0001 | ||

| Married | 397 (29.5%) | 3.46 | |

| Divorced | 576 (42.7%) | 3.78 | |

| Widowed | 183 (13.6%0 | 3.78 | |

| Never married | 192 (14.2%) | 3.71 | |

| Income per member of household | (F) <0.0001 | ||

| $0–5000 | 354 (27.5%) | 3.82 | |

| $5001–10,000 | 646 (50.2%) | 3.75 | |

| Over $10,000 | 287 (22.3%) | 3.33 | |

| Currently employed | (t) <0.0001 | ||

| No | 937 (78.1%) | 3.80 | |

| Yes | 262 (21.9%) | 3.08 | |

| Years in the US | (F) 0.07 | ||

| 0–10 | 70 (5.5%) | 3.56 | |

| 11–20 | 126 (9.3%) | 3.50 | |

| 21–30 | 206 (16.1%) | 3.59 | |

| 31–40 | 472 (36.8%) | 3.70 | |

| 41–50 | 330 (25.7%) | 3.75 | |

| Over 51 | 78 (6.1%) | 3.54 | |

| Language of interview | |||

| Only Spanish | 1164 (86%) | 3.71 | (F) <0.01 |

| English and Spanish | 143 (10.6%) | 3.56 | |

| Only English | 45 (3.3%) | 3.24 | |

| Poverty Index | |||

| Above | 531 (41.3%) | 3.47 | (t) <0.0001 |

| Below | 756 (58.7%) | 3.82 | |

Self Rated Health is used as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicative of poor health

Demographic information

Demographic data include age, education, marital status, length of residency in the United States, household composition, current employment status, and average household income per household member (calculated from the total household income divided by number of people in the household).

Dependent variable

SRH is the key dependent variable and it was assessed with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5: 1- Excellent (Excelente), 2- Very Good (Muy Buena), 3- Good (Buena), 4- Fair (Regular), 5 -Poor (Mala). This measure has been used with different populations, including Latinos (Finch et al., 2002, Idler and Benyamini, 1997). It has been pointed out that the widely used translation of the item into Spanish, particularly of the “fair/regular” category, might not fully coincide with the meaning of the English version (Bzostek et al., 2007, Finch et al., 2002). Still, even if we assume there are nuances in the meanings of these categories across the two languages, we are confident that there is an obvious gradient in the meaning across the 5 points in the scale in both the English and Spanish versions of this item. Further, in the multivariate models the language of interview is included as a control to account for any potential influences of language of interview (see below).

Independent variables

Medical Conditions

The number of existing medical conditions was identified through self-reporting. Participants were asked to identify, from a list of questions, which medical conditions had been diagnosed by a health care provider (rather than just being asked if they have symptoms). The 16 conditions include diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, heart attack and heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, liver or gallbladder, stomach and intestinal disorders, kidney, Parkinson’s disease, osteoporosis, cancer, tuberculosis, hepatitis and HIV/AIDS. A summated score of the number of existing conditions was calculated for this measure.

Functional status was evaluated through a self-report questionnaire assessing their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL). We used a modified Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale (Katz et al., 1963), employed in previous studies with Puerto Rican adults. The 12 activities, for which respondents are asked if they experience difficulty, are related to eating, getting dressed, bathing, toileting, walking at a distance, as well as walking inside one’s home. The Cronbach Alpha for the ADL scale was 0.91.

Allostatic Load

This indicator of biological functioning is a summary measure, containing 11 components (Mattei et al., 2010). Allostatic load is calculated by identifying the clinical cut-off values for 11 parameters, and assigning a point for each parameter for which the respondent is above (or below) the relevant cut-off point, which can be different for men and women. Thus, each point on the allostatic load measure indicates that, for a respondent, a particular component value did not fall within the healthy range. Respondents that reported taking medications for hypertension, diabetes, lipid-lowering drugs and testosterone, had points added to their allostatic load score—even if the value of the component was within the healthy range. This prevents the existing accumulated dysregulation from being obscured by the effects of medication and more precisely reflects the cumulative load experienced by the respondent. The components of the summary measure of allostatic load are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cutoff points for Allostatic Load Components (Mattei et al, 2010) with percent of the sample above or below the cut-off points plus t-test for differences in SRH 1

| Biomarker | Cut-off Points | % over or under cutoff/or medication | Difference in SRH between those in the unhealthy range vs. healthy range for the given biomarker (t test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose tissue deposition

| |||

| Waist Circumference: WC (cm) | Men > 102 Women > 88 |

70.3% | 8.19*** |

|

| |||

| Cardiovascular system

| |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure: SBP (mmHg) | > 140 or taking medications | 65.9% | 5.26*** |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure: DBP (mmHg) | > 90 or taking medications | 62.2% | 5.35*** |

|

| |||

| Lipid metabolism

| |||

| Total Cholesterol: TC (mg/dl) | >= 240 or taking medications | 44.9% | 3.79*** |

| High Density Lipoprotein: HDL-C (mg/dl) | < 40 or taking medications | 60.4% | 3.52*** |

|

| |||

| Glucose metabolism

| |||

| Glycosylated hemoglobin: HbA1c (%) | > 7 or taking medications | 40.4% | 6.35*** |

|

| |||

| Hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis | |||

|

| |||

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate: DHEA-S (ng/mL) | Men <= 590 or taking medications Women <= 369 or taking medications |

28.1% | 3.38** |

| Cortisol: (μg/g creatinine) | Men >= 41.5 Women >= 49.5 |

15.7% | −0.18 |

|

| |||

| Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) | |||

|

| |||

| Norepinephrine: (μg/g creatinine) | Men >= 30.5 Women >= 46.9 |

34.1% | −0.44 |

| Epinephrine: (μg/g creatinine) | Men >= 2.8 Women >= 3.6 |

33.4% | −1.08 |

|

| |||

| Inflammation

| |||

| C-reactive protein: CRP (mg/L) | > 3 | 55.7% | 4.59*** |

The separate components of allostatic load are used as binary variables: one point is given if it is in the unhealthy range (above or below relevant cutoff points) and 0 points if it is in the healthy range. The t value is for the difference in SRH for people who have received a point for being in the unhealthy range for the component, compared to those who have not. Self Rated Health is used as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicative of poor health;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p<0.001

Depressive symptoms

We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) to assess depressive symptoms. Appropriate validity for older adults (Radloff, 1986), as well as for Hispanics (Moscicki et al., 1987), including the Puerto Rican population in the US mainland (Falcón et al., 2009, Falcón and Tucker, 2000, Mahard, 1988, Potter et al., 1995) has been illustrated for this scale and it is widely used. The scale assesses depressive mood during the past week, and is constructed from 20 items on a 4-point scale. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the CES-D scale was 0.91.

Health risk behaviours

Participants were asked about smoking and alcohol use, with items adapted from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1996). Respondents were asked whether they have ever smoked, whether they currently smoke or whether they have stopped. They were considered as never having smoked if they had consumed less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Respondents who had had less than 12 drinks in their lifetime were considered as never having been drinkers. If they had had more than 12 drinks, but had stopped drinking, they were considered past drinkers.

Perceived discrimination was assessed through one item “Have you ever experienced discrimination as a result of your race, ethnicity or language?” The possible responses were ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Social activities

We used the Social and Community Support and Assistance Questionnaire, developed for the Massachusetts Hispanic Elderly Study (MAHES (Falcón and Tucker, 2000)and particularly the subscale for social activities during the past two weeks, such as participation in volunteer activities, hobbies, visit neighbours, etc.

Social support

We used the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (Norbeck, 1995). This instrument asks respondents to list up to 16 important people from whom they receive support in their daily lives. Then, respondents were asked to rate the extent of support provided by each person on a 5-point scale. Emotional support provided by each person in the network includes dimensions of affect and affirmation (“How much does this person make you feel liked or loved?”; “How much does this person make you feel respected or admired?”). Tangible support (aid) measures the instrumental aspects of network support (“If you need to borrow $10, a ride to the doctor, or some other immediate help, how much could this person usually help”?). Respondents were also asked to give the duration of the relationship and the frequency of contact with each member within their social network.

Poverty Index

Poverty guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Services (Department of Health and Human Services, 2007 ) based on total household income and the number of people within the household were used to calculate poverty status. Participants were classified as falling below or above the poverty line using household income thresholds specific for the year in which the interview took place.

Acculturation

The preferred language for 7 different daily activities (Marin and Gamba, 1996), adapted for the Puerto Rican population in the Massachusetts Hispanic Elderly Study (MAHES) (Falcón and Tucker, 2000), was used as a proxy for acculturation. The variable indicates the percentage of daily activities (watching television, reading, speaking with neighbours, etc.) in which English language was the language of choice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 software. We conducted correlation analysis, cross-tabulations and ANOVA to test for bivariate associations and differences between groups. Generalized Linear Models (GLM) were used to assess associations between SRH as a continuous outcome variable and multiple predictor variables, adjusting for covariates. GLM is an appropriate technique for this analysis, as it generalizes an ordinary regression model. It was preferred over a cumulative logistic model, as the proportional odds assumption indicated that the odds ratios for the predictor variables were not constant across all categories of SRH.

Tests for multicollinearity supported the inclusion in the GLM of all the predictors described above, but keeping only emotional support and social activities from the social support variables. The linearity of the relationship between SRH and all the included predictors was satisfied. Moreover, to avoid biased or misleading interactions due to the potential nonlinearity of Language Acculturation, we re-ran the model using a binary variable for acculturation (instead of a continuous variable) but the results did not differ. The Q-Q plot for the residuals suggested that the normality assumption was met. Some participants had a residual larger than 2; however, as exclusion of these did not affect the model, we include all observations. We examined independent contributions of predictors of SRH, and also tested for interaction effects, further described below.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample available for analysis was n=1357, 30 percent (n=401) men and 70% (n=956) women (Table 1). Their ages ranged from 45 to 75 years, with a mean of 57.2 (SD=7.6). The largest education level group had completed 12th grade (36.7%); half had income per household member between $5001 and $10,000 per year; and only 21.9% were currently employed. While 96% of the sample was born on the island of Puerto Rico, more than 68% had lived in the US for more than 30 years. At the same time, 75.5% spoke only or mostly Spanish. The majority of participants (86%) completed the interview in Spanish, 3% completed it fully in English and 11% in a combination of the two languages (Table 1). These sample characteristics are generally similar to the Puerto Rican population in the region; however the comparison we conducted with the Census data available at that time illustrates that our sample over represents women, including women who are not employed (Authors). Employment rates in the Boston area of the Northeastern United States are generally the lowest for Puerto Ricans compared to other Latino groups (Granberry and Rustan, 2012), but it may be even lower for our sample, due to the over-representation of women, for whom there is an employment gap (England et al., 2004).

Dependent variable

The majority of respondents stated that their health was fair (56.9%), and 13.2% described it as poor; only 5% rated their health as excellent, 5.8% as very good, and 19.2% as good (Table 1). The mean value for SRH was 3.7 for our sample (1 being excellent, and 5 being poor). Women rated their health as poorer than men (P<0.0001). SRH was lower for people with fewer years of education (F=13.0, P<0.0001); older age (F=9.54, P<0.0001), lower income (F=25.9, P <0.001); and who were not employed at the time of the survey (t= 10.3, P=0.0001). People who were married rated their health higher compared to those who were divorced, separated, widowed or not married (F= 10.3, P<.0001). Length of residency on the mainland US was not related to SRH. Respondents who spoke only or mostly Spanish reported lower SRH than those who spoke both languages or only English (F=12.6, P<0.0001). SRH was lower for the 96.7% who completed the interview in either Spanish or in both Spanish and English, compared to the 3.3% who completed the interview fully in English (F=6.42, P<0.01). Thus, to limit the effect of language of interview and potential translation issues regarding the SRH categories, the language of interview was controlled in all subsequent analyses.

Relative to other studies, our sample was more likely to report poor self-rated health. For example, a study in Canada with older adults from many ethnicities found that 43.4% rated their health as poor/fair, relative to 70.1% of our sample (Menec et al., 2007). Another U.S. study, with older adults from different ethnicities, reported that 26% of Latinos rated their health as fair and 13% as poor (August and Sorkin, 2010). To some extent this difference could be due to the demographic composition of our sample of older Puerto Rican adults, and to the health disparities which we will discuss below.

Independent variables and bivariate analyses

Medical conditions

The number of reported medical conditions ranged from 0 to 12 with a mean of 3.0 conditions (SD=1.9). Women reported more existing medical conditions than men (P<0.001). Higher number of existing medical conditions was correlated with poor ratings of SRH (r=0.30, P=<0.0001) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of key independent variables with SRH: Correlations for continuous variables and ANOVA for categorical variables

| Mean and SD | Corr. with SRH1 (r) | p (for r) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allostatic load | 4.37 (1.80) | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD) | 20.2 (13.2) | 0.35 | <0.0001 |

| Number of medical conditions | 2.98 (1.88) | 0.30 | <0.0001 |

| Activities of daily living | 4.03 (5.14) | 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Acculturation | 24.1 (22.4) | −0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Social Support Emotional | 14.0 (2.99) | −0.13 | <0.0001 |

| Social activities | 5.98 (2.36) | −0.18 | <0.0001 |

| N and % of sample | SRH Mean | p (for F) | |

| Drinker | <0.0001 | ||

| Never drank | 404 (30%) | 3.83 | |

| Drank in the past, but not currently | 408 (30.3%) | 3.73 | |

| Currently drinks | 536 (39.8%) | 3.53 | |

| Smoker | 0.75 | ||

| Never smoked | 614 (45.8%) | 3.67 | |

| Smoked in the past, not currently | 396 (29.5%) | 3.70 | |

| Currently smokes | 331 (24.7%) | 3.65 | |

| Perceived discrimination: | |||

| Yes | 414 (36.9%) | 3.59 | 0.16 |

| No | 709 (63.1%) | 3.68 |

Variables other than age and sex are adjusted for age and sex for significance testing of correlations; Self Rated Health is used as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicative of poor health.

Activities of Daily Living (ADL)

Level of difficulty with ADL was assessed for 12 activities. Summary scores ranged from 0 to 36, with a mean of 4.0 for the sample, with women having, on average, more difficulty than men (Table 2). Problems with ADL were positively correlated with poor SRH (r=0.32, P<0.0001).

Depressive Symptoms (CESD)

The average CES-D score for the sample was 20.2, (ranging from 0 to 60), which is high, considering that a score >16 is considered indicative of moderate depressive symptoms (Table 2). Based on published criteria (Radloff, 1986), 43.4% of participants had scores that placed them at possible clinical depression level symptomatology. Women had higher average scores on the CES-D than men (men mean = 16.5; women mean = 21.7, P <0.0001). Higher depressive symptoms correlated with poorer SRH (r=0.35, P <0.0001).

Health risk behaviors

Of the participants, 30% had never consumed alcohol, 30.3% had consumed in the past and 39.8% were current drinkers. Men (51%) were more likely to be current drinkers than women (35.1%), (P<0.0001). Current drinkers rated their health as better (mean=3.52) compared to those who had never consumed alcohol (mean=3.83) (F=13.9, P<0.0001), (Table 2). Fewer than half of the respondents, 45.8%, had never smoked, 29.5% had smoked in the past and 24.7% were current smokers. When compared to women (20.7%), men (34.4%) were more likely to be current smokers (P< 0.0001). Smoking behaviour was not related to SRH (Table 2).

Social context

Characteristics of the social context of the respondents were indicated by the different dimensions of social support available to them, the extent of being engaged in social activities and, on the other hand, their experiences with poverty and discrimination. All dimensions of social support and social activities were weakly, but significantly correlated with SRH in bivariate analysis (results shown only for emotional support and social activities in Table 2). Perceived discrimination was not associated with SRH (Table 2). Those above the poverty level had better SRH, compared to those who were below it (P<0.0001) (Table 1).

Allostatic load and components

The summary measure of allostatic load was calculated based on the 11 components shown in Table 3. For many of the components of allostatic load, a large percentage of the sample was classified as at risk based on clinical cut-off points (e.g. high waist circumference (WC), 70.3%; high systolic blood pressure (SBP) 65.9%; and low HDL cholesterol, 60.4%). High allostatic load was significantly correlated with poor SRH (r= 0.18, P<0.0001) (Table 2). Most of the individual biological components of allostatic load were also significantly associated with SRH at the bivariate level, with poor SRH being more likely from participants with biomarker measures beyond cut-off points indicative of clinical problems: WC, systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure, total cholesterol, (TC) HDL cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin (HgA1c), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) (Table 3).

Moderator

Acculturation

Men (mean = 29.4) were more acculturated than women (mean = 21.9, t = 5.64, P < 0.001), as indicated by English language use in daily activities. Higher acculturation was significantly associated with better SRH (r= −0.21, P< 0.0001) (Table 2). Additionally, higher acculturation was associated with other indicators of better health: fewer chronic medical conditions (r= −0.18, P< 0.0001), fewer problems with ADL (r= −0.17, P< 0.0001), and fewer depressive symptoms (r= −0.08, P< 0.01). The correlation between acculturation and allostatic load was negative and approached significance (P=0.052) (Results not shown).

Multiple regression analysis

We conducted generalized linear modeling (GLM), predicting SRH from physical health, psychological health and social context, and controlling for age, gender, education and language of interview. Demographic variables are added in the first model shown in Table 4. Older age, and being female were associated with poorer SRH while more years of education was associated with better SRH. The language of interview was not associated with SRH in the multiple regression model. In the second model, medical conditions, high ADL score and high allostatic load were each significantly associated with poorer SRH. In Model 3, the psychological health indicator (depressive symptoms) was added and was significantly associated with SRH. The physical health indicators already in the equation continued to be independently associated with SRH. Model 4 introduced health behaviors (smoking and alcohol consumption), which showed no significant association with SRH. The social dimension variables were added in Model 5 with significant effects for emotional support but not for social activities, experiences of discrimination or poverty level. In this final model, allostatic load, number of medical conditions, ADL score and depressive symptoms continued to be independently associated with SRH. Language acculturation was included in all of the models as a predictor (Table 4), and was later also tested as a moderator.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting Self-rated Health.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | Physical Health | Psychological Health | Health Risk Behaviors | Social Dimensions | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | |

| Age | .07** | 0.003 | −0.02 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.004 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| At least some graduate school | −.09** | 0.18 | −.04 | 0.22 | −.02 | 0.22 | −.02 | 0.22 | −.01 | 0.23 |

| Some college OR bachelor’s degree | −.12*** | 0.09 | −.05 | 0.10 | −.03 | 0.10 | −.02 | 0.10 | −.01 | 0.10 |

| 9th–12th grade | −.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| 5th – 9th grade | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08* | 0.07 | 0.08* | 0.07 | 0.08** | 0.07 | 0.08* | 0.07 |

| Gender | −.15*** | 0.05 | −.08** | 0.06 | −.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Interview in English and both Spanish and English | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.005 | 0.08 | −0.006 | 0.09 |

| Acculturation score | −.09* | 0.001 | −.09** | 0.001 | −.09** | 0.001 | −0.07 | 0.001 | ||

| Allostatic load | .06* | 0.01 | .08** | 0.01 | .08** | 0.01 | .09** | 0.01 | ||

| Number of medical conditions | .19*** | 0.01 | .15*** | 0.01 | .15*** | 0.01 | .16*** | 0.01 | ||

| Activities of daily living | .22*** | 0.006 | .15*** | 0.006 | .15*** | 0.006 | .13*** | 0.006 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | .24*** | 0.002 | .24*** | 0.002 | .23*** | 0.002 | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| Never drank | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Drank in the past | −.01 | 0.06 | −.02 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Never smoked | −.04 | 0.07 | −.03 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Smoked in the past | −.01 | 0.07 | −.009 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Emotional support | −.06* | 0.009 | ||||||||

| Social activities | −.03 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Poverty index | −.02 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Perceived discrimination | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | |||||

| F for change in R2 | 13.29*** | 23.79*** | 26.84*** | 20.05*** | 16.20*** | |||||

Self Rated Health is used as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicative of poor health;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Reference category for Education is “No schooling or less than 5th grade”; for Gender is “Female” ; for Language of Interview is “Spanish”; for Drinker is “Currently Drinks”, for Smoker is “Currently Smokes”

Testing for moderation effects of acculturation

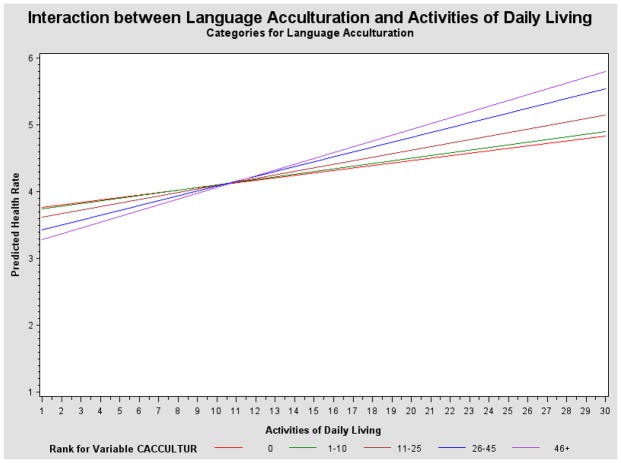

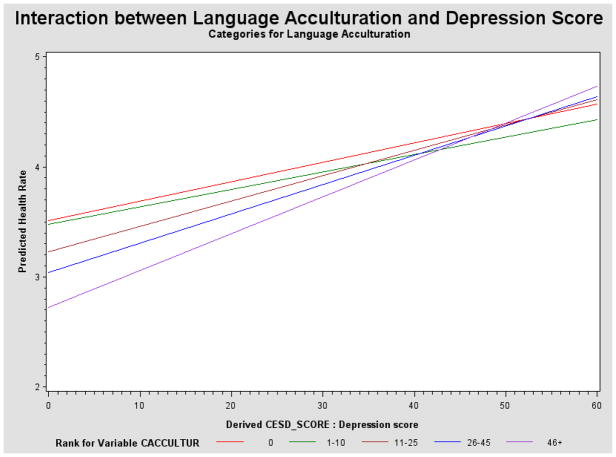

Using GLM, we tested whether acculturation was a moderator of the effects of the above predictors on SRH. A moderator is a variable which influences the effect of the predictor on the dependent variable (Baron and Kenny, 1986). After our final model was constructed, we tested for significant interactions between the variables that proved to be the strongest independent predictors of SRH (allostatic load, medical conditions, ADL score and depressive symptoms) and language acculturation. To test the effect of the interactions separately, we conducted four different models. In each, we controlled for the same demographic and psychosocial variables. A significant P value (P< 0.01) for the interaction term was interpreted as an indication of effect modification. There were significant interaction effects for acculturation with ADL (β= 0.13, P < 0.01)(Figure 1) and with depressive symptoms (β=0.18, P < 0.01)(Figure 2) in relation to SRH. At low levels of problems with ADL, those more acculturated assessed their health more positively; and at higher levels of problems with ADL, they assessed their health more negatively than people with lower levels of acculturation, who show a flatter slope. Thus there is less variation in reporting of SRH among those with lower acculturation and stronger associations between measured variables and SRH among those more acculturated. With depressive symptoms, those less acculturated reported worse SRH at low levels and the differences in reporting of SRH according to acculturation disappeared at high levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Interaction between language acculturation and ADL

Significant at the P<0.01 level

Figure 2.

Interaction between language acculturation and CESD

Significant at the P<0.01 level

Discussion

We aimed to examine what dimensions of physical, psychological and social health adult Puerto Ricans integrate into their assessments of overall health. This is important, as some previous findings have indicated that Latinos tend to somaticize and exaggerate physical symptoms (Angel and Guarnaccia, 1989), while others have illustrated that SRH assessments may actually underestimate health risk for vulnerable socioeconomic groups (Dowd and Zajacova, 2010).

The first important finding of our study is that, overall, our respondents did not rate their health as good—which is of concern, considering the strong predictive power of this indicator (Idler and Benyamini, 1997). Poorer ratings of SRH were associated with negative objective and self-reported indicators of physical and psychological health, while social integration and acculturation were associated with better SRH.

Multiple dimensions of health were included in the rating of overall health. Assessments of SRH were most strongly associated with allostatic load, medical conditions, ADL and depressive mood, controlling for demographic indicators. Thus, accumulation of physiological dysregulation, (as indicated by a combination of adipose tissue deposition, the functioning of the HPA system, the SNS, the CVS, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism and inflammation) appears to be felt and is reflected in assessments of overall health. This was also clear for several of the separate biomarkers indicative of poor health. The fact that allostatic load and separate biomarkers showed a strong independent association with assessments of SRH is an important finding, as it illustrates the biological resonance of this integrative measure of overall health. We can hypothesize that the state of the biological systems (even though they might not have been manifested into evident disease) are sensed and brought into the processes of evaluation of overall health, which according to (Jylhä, 2009) are active individual decision processes and choices (which could be rational, logical, or intuitive) (Jylhä, 2010).

Psychological well-being and the perception of having emotional support are also integrated into SRH. Other research has also shown that Latinos integrate mental health status (depression) into their assessment of health, however, they are not more likely to do so than other ethnic groups, including non-Hispanic whites, (Bzostek et al., 2007), and thus do not appear to be somaticizing depressed mood into their assessment.

Puerto Rican adults appeared to be less inclined to take into account experiences of discrimination, poverty and participation in social activities into these assessments of self-rated health, although these experiences may contribute indirectly, through their effects on physical and mental health measures. Health behaviors were also not independently related, thus we can conclude they are not taken into account to a significant extent when assessing SRH.

Additionally, language acculturation contributed to the different assessment of overall health. More highly acculturated individuals reported better health, and better health for those more acculturated in our sample was also confirmed by other measures of physical health (medical conditions, problems with activities of daily living, and most biological components of allostatic load) and psychological (depressive mood). The direction of this association is opposite to other findings in Latino populations (primarily Mexican American), that have found an inverse relation between acculturation and health (Schwartz et al., 2010) and has been termed the Latino health paradox (Morales et al., 2002).

Another important finding of our study is that the relationship between SRH assessments and other health indicators differed by level of acculturation – with stronger associations between health indicators and SRH in those more acculturated and more of a flattening among those less acculturated. When in good health, it appears that those with low acculturation may report their SRH as lower for the same level of some indicators. At higher levels of health problems, the differences by acculturation disappeared or reversed. With greater functional limitations, the associations were inverted – those with higher acculturation reported poorer health for the same level of functional problems, compared to people with lower acculturation. The association between SRH and measures of health was, therefore, stronger in those more acculturated, than among those less acculturated. This is consistent with the findings of Finch et al (2002), who found that SRH predicted mortality more strongly for more acculturated Latinos, than for those less acculturated.

This observation suggests that less, vs. more, acculturated Puerto Rican adults may be less likely to rate their health at the extremes of excellent or poor. When health is poor, as indicated for example by functional abilities, those more closely tied to Puerto Rican culture may understate the severity of their health problems when assessing SRH, as they may be more inclined to tolerate functional limitations or be more likely to take them as a given of the aging process. As discussed by others, the concept of “normality” in relation to health may differ across cultures, or in this case, according to acculturation (Idler and Benyamini, 1997). This is opposite of the view that less acculturated Puerto Ricans would be more likely to somaticize their complaints and to exaggerate poor health (Angel and Guarnaccia, 1989).

Limitations

A limitation of this analysis is the cross-sectional design, as well as the self-reported nature of some of the independent variables. ADL and depressive symptoms are self-reported measures of health problems and, thus, one can ask whether the initial assessment of these problems is influenced by acculturation, thereby affecting the interaction of acculturation and the given variable. However, we have previously demonstrated that self-reported ADL assessments were highly correlated to performance-based measures of physical function (Authors).

We also need to note that although we tested the relevance of many physical, psychological and social indicators for assessments of SRH, the explained variance in our models was 26%. This could be an indication that we have not included all relevant psychological dimensions, life events, coping styles, personality (Mackenbach et al., 2002) or early life and family history (Singh-Manoux et al., 2006). Additionally, we know that in other studies, the reported explained variance in similar models testing multiple determinants of SRH has been higher; for example in the two studies reported by Singh-Manoux (2006), the determinants studied explained 34.7% and 41.4% of the variance respectively; and in the study by Benyamini et al (1999), 42% of the variance was explained. Thus, the lower explained variance could in itself be an indication of the differential validity of SRH for this population as a whole, or for sub-populations with different acculturation.

Conclusions

The Puerto Rican population in the US is a group with large health disparities when compared to the general population, illustrated through high burden of physical and psychological illness, social isolation and encounters with discrimination. We asked how the self-ratings of health made by this population of Puerto Rican adults correspond to objective and self-reported measures of health and disease, as well as to their experiences in the social context. We conclude that adults integrate information from multiple sources in their self-assessment of overall health, including social support, psychological mood, objective biological indicators (as operationalized by chronic conditions), allostatic load and separate biomarkers. Additionally, acculturation was related to health, in the sense that integrating into mainland society appears to be protective. Acculturation also moderated the way in which this group assessed their overall health, with stronger associations between health indicators and SRH among the more acculturated.

Thus, our study confirms that the relevance of different dimensions of well-being for assessing SRH varies by acculturation – according to one conceptual model (Jylhä, 2009) this suggests that Puerto Ricans with different cultural experiences could have different perceptions of health and how to evaluate it. The concept of self-rated health, while useful for the Puerto Rican group as a whole, appears to vary in meaning, depending on acculturation. In cases of poorer health, SRH might even understate existing health problems and thus conceal disparities. Our study provides additional illustration for the differential validity of SRH not only among different ethnicities, but also within ethnicities with different experiences of acculturation.

Key Messages.

Adults integrate multiple indicators in assessments of self-rated health.

The accumulation of physiological dysregulation (allostatic load), psychological distress, functional limitations, diseases and emotional support are integrated into SRH while experiences of discrimination and poverty less so.

The concept of self-rated health, while useful for the Puerto Rican group as a whole, appears to vary in meaning, depending on acculturation.

When in poor health, those more closely tied to Puerto Rican culture may understate the severity of their health problems when assessing their health and this could conceal health disparities.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health, who have funded this project, under grants P01AG023394 and P50HL105185.

References

- Abdulrahim S, Baker W. Differences in self-rated health by immigrant status and language preference among Arab Americans in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:2097–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel R, Guarnaccia PJ. Mind, body and culture: somatization among Hispanics. Social Science and Medicine. 1989;28:1229–1238. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August KJ, Sorkin DH. Racial and ethnic disparities in indicators of physical health status: Do they still exist throughout late life? Journal Of The American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58:2009–2015. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and research considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Self-assessments of health: What do people know that predicts their mortality? Research on Aging. 1999;21:477–500. [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Elderly people’s ratings of the importance of health-related factors to their self-assessments of health. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1661–1667. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzostek S, Goldman N, Pebley A. Why do Hispanics in the USA report poor health? Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:990–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda-Sceppa C, Price LL, Noel SE, Bassett Midle J, Falcón LM, Tucker KL. Physical function and health status in aging puerto rican adults: the Boston puerto rican health study. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22:653–672. doi: 10.1177/0898264310366738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandola T, Jenkinson C. Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups. Ethnicity & Health. 2000;5:151–159. doi: 10.1080/713667451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chvu LWJY. Doctor of Philosophy. University of Califormia; 2008. Cumulative physiological dysregulation among women in the United States: Sociodemographic correlates and implications for self-rated health. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. Federal Register/Notices. 2007;72:3147–3148. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JB, Zajacova A. Does self-rated health mean the same thing across socioeconomic groups? Evidence from biomarker data. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P, Garcia-Beaulieu C, Ross M. Women’s employment among Blacks, Whites and three groups of Latinas: Do more privileged women have higher employment. Gender & Society. 2004;18:494–509. [Google Scholar]

- Falcón LM, Todorova I, Tucker K. Social support, life events, and psychological distress among the Puerto Rican population in the Boston area of the United States. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13:863–873. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcón LM, Tucker KL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S108–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Hummer RA, Reindl M, Vega WA. Validity of self-rated health among Latino(a)s. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:755–759. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberry P, Rustan S. Latinos in Massachusetts selected areas. Boston.. Boston: Gastón Institute Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Halford C. Endocrine measures of stress and self-rated health A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;55:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00634-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Epstein AM, Mcneil BJ. Multidimesnionality of health status in an elderly population: Construct validity of a measurement battery. Medical Care. 1989;27:S168–S177. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Goldberg LR, Vogt TM, Hillier TA, Dubanoski JP. Using physiological dysregulation to assess global health status: Associations with self-rated health and health behaviors. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:232–241. doi: 10.1177/1359105308100207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson D, Von Thiele Schwarz U, Lindfors P. Self-rated health and allostatic load in women working in two occupational sectors. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:568–577. doi: 10.1177/1359105309103576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M, Deeg DJH. A commentary on Marja Jylhä’s “What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model”(69:3, 2009, 307–316) Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:652–654. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Hudson SV, Leventhal H. The meanings of self-ratings of health: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Research on Aging. 1999;21:458–476. [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M. Self-rated health between psychology and biology. A response to Huisman and Deeg. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:655–657. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Jokela J, Heikkinen E. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B:SI44–SI52. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.3.s144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G, Baron-Epel O. What lies behind the subjective evaluation of health status? Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1669–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi KM, Prus S, Lin Z. Ethnic differences in self-rated and functional health: Does immigrant status matter? Ethnicity & Health. 2008;13:129–147. doi: 10.1080/13557850701830299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kómár M, Nagymajtényi L, Nyári T, Paulik E. The determinants of self-rated health among ethnic minorities in Hungary. Ethnicity & Health. 2006;11:121–132. doi: 10.1080/13557850500485378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekander M. Self-rated health is related to levels of circulating cytokines. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:559–563. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000130491.95823.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Simon JG, Looman CWN, Joung IMA. Self-assessed health and mortality: Could psychosocial factors explain the association? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:1162–1168. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahard RE. The CES-D as a measure of depressive mood in the elderly Puerto Rican population. Journal Of Gerontology. 1988;43:24–25. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.1.p24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei J, Demissie S, Falcón LM, Ordovas JM, Tucker K. Allostatic load is associated with chronic conditions in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2010;70:1988–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcewen BS. Stress, adaptation and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals Of The New York Academy Of Sciences. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menec VH, Shooshtari S, Lambert P. Ethnic differences in self-rated health among older adults: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Journal of Aging and Health. 2007;19:62–86. doi: 10.1177/0898264306296397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales L, Lara M, Kington R, Valdez R, Escarce J. Socioeconomic, cultural and behavioral factors affecting Hispanic health outcomes. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2002;13:477–503. doi: 10.1177/104920802237532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki E, Rae DS, Reiger E, Locke B. Depression among Mexican Americans, Cubans and Puerto Ricans. In: GAVIRIA M, ARANA J, editors. Health and behavior: Research agenda for Hispanics (Simon Bolivar Research Monograph Series I) Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nakata A, Takahashi M, Otsuka Y, Swanson NG. Is self-rated health associated with blood immune markers in healthy individuals? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;17:234–242. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nhanes The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 1996 Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nh3data.htm.

- Norbeck J. [Accessed November 5, 2007];Scoring instructions for the Norbeck social support questionnaire, revised 1995. 1995 Unpublished Manual [Online]. Available: http://nurseweb.ucsf.edu/www/ffnorb.htm.

- Potter LB, Rogler LH, Moscicki EK. Depression among Puerto Ricans in New York City: The Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1995;30:185–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00790657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The use of the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale with older adults. Clinical Gerontology. 1986;5:119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetterly SM, Baxter J, Mason LD, Hamman RF. Self-rated health among Hispanic vs Non-Hispanic white adults: The San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1798–1801. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, Zins M, Marmot M, Goldberg M. What does self rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60:364–372. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomten SE, Høstmark AT. Self-rated health showed a consistent association with serum HDL-cholesterol in the cross-sectional Oslo Health Study. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:278–287. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker KL, Mattei J, Noel SE, Collado BM, Mendez J, Nelson J, Griffith J, Ordovas JM, Falcón LM. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:107–107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unden AL, Andereasson A, Elofsson S, Brismar K, Mathsson L, Ronnellid J, Lekander M. Inflammatory cytokines, behavior and age as determinants of self-rated health in women. Clinical Science. 2007;112:363–373. doi: 10.1042/CS20060128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorisalmi M, Pietilä I, Pohjolainen P, Jylhä M. Comparison of self-rated health in older people of St. Petersburg, Russia, and Tampere, Finland: how sensitive is SRH to cross-cultural factors? European Journal of Ageing. 2008;5:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0093-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]