Abstract

Rationale

Clinical trials show that chronic cocaine users suffer from sleep disturbances and preclinical research has shown that acute sleep deprivation increases the rate of cocaine self-administration in rats.

Objective

This study examined the effect of cocaine self-administration on behavioral indices of sleep, and alternatively the effect of sleep disruption on cocaine-maintained responding by rhesus monkeys.

Methods

Seven adult rhesus monkeys, fitted with Actical® activity monitors, were trained to respond under a concurrent choice paradigm with food (three 1.0-g pellets) and cocaine (0.003–0.3 mg/kg) or saline presentation. For each monkey the lowest preferred dose of cocaine (> 80% cocaine choice) was determined. Activity data were analyzed during lights out (2000-0600) to determine sleep efficiency, sleep latency and total activity counts. Subsequently, the monkeys were sleep disrupted (awaken every hour during lights-out period) the night prior to food-cocaine choice sessions.

Results

Self-administration of the preferred dose of cocaine resulted in a significant decrease in sleep efficiency, with a significant increase in total lights-out activity. Sleep disruption significantly altered behavioral indices of sleep, similar to those seen following cocaine self-administration. However, sleep disruption did not affect cocaine self-administration under concurrent choice conditions.

Conclusions

Based on these findings, cocaine self-administration does appear to disrupt behavioral indices of sleep, although it remains to be determined if treatments that improve sleep measures can affect future cocaine taking.

Keywords: cocaine, sleep, sleep disruption, monkeys

Introduction

Drug addiction is an economically taxing brain disease, costing approximately $593 billion annually, which currently has limited treatment options (Harwood 2000; National Drug Threat Assessment 2010; NIDA 2010; CDC 2012). There are an estimated 22.1 million people in the U.S. that met DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse or dependence in 2010, of which 1.5 million had cocaine dependence or abuse (NSDUH 2010). At present there are no medically approved treatments for cocaine addiction. Thus, treating cocaine addiction represents an important area of concern to healthcare professionals and scientists. Integral to finding appropriate treatment strategies is a better understanding of the physiological consequences of cocaine use.

It is known that most drugs can affect sleep patterns, usually adversely, impacting both the duration and frequency of sleep stages (Barkoukis and Avidan 2007) and literature suggests cocaine abusers encounter a vicious cycle between relapse and sleep dysregulation when trying to abstain from the drug. Thus, it is possible that sleep disturbances may contribute to cocaine addiction and not just be a consequence of the illness. It has been reported that current cocaine use is associated with prolonged wakefulness and hypersomnia is present during early withdrawal (Morgan et al. 2008). Research has shown that with sustained abstinence from cocaine, cocaine abusers exhibit decreased sleep, impaired vigilance and sleep-dependent procedural learning, and spectral activity suggestive of chronic insomnia (Morgan et al. 2006). These sleep disturbances may persist for months to years following abstinence (Gillin et al. 1994; Clark et al. 1998; Drummond et al. 1998; Landolt and Gillin 2001) making these sleep disturbances a continuing problem for abstinent cocaine users. It has also been shown that abstinence-associated sleep-dependent learning deficits are related to changes in sleep architecture supporting the concept that treatments directed at improving/aiding sleep could be beneficial in offsetting physiological consequences of cocaine abstinence (Morgan et al. 2008). A recent study in monkeys reported that methamphetamine self-administration increased sleep latency and decreased sleep efficiency (Andersen et al. 2012a). One goal of the present study was to extend these findings to cocaine self-administration.

Clinical literature suggests that sleep deprivation is a factor that can induce patients to relapse to drug-taking behavior. Consistent with this clinical observation, preclinical studies have shown that acute sleep deprivation increased the rate at which rats’ self-administered cocaine (Puhl et al. 2009). There is evidence to support a relationship between the effects of sleep deprivation and cocaine self-administration. For example, Volkow and colleagues showed that one night of sleep deprivation in humans caused decreases in dopamine (DA) D2-like receptor availability in the striatum and thalamus but did not affect DAT availability (Volkow et al. 2008). Subsequent studies by this group involved administering methylphenidate to sleep-deprived and rested-waking state individuals and found that the ability to elevate DA was not influenced by sleep deprivation, suggesting D2-like receptor downregulation, rather than elevated DA concentrations as the mechanism mediating the effects of methylphenidate on sleep (Volkow et al. 2012). Of relevance to the present study, there is evidence of an inverse relationship between DA D2-like receptor availability and cocaine reinforcement (Volkow et al. 1999; Morgan et al. 2002; Nader et al. 2006; Dalley et al. 2007) and cocaine decreases DA D2-like receptor availability (Volkow et al. 1999; Martinez et al. 2004; Nader et al. 2006), so a second goal was to examine how sleep disruption affected cocaine self-administration in our monkey model.

In the present study, rhesus monkeys were trained to self-administer cocaine under a concurrent schedule of reinforcement with food pellets as the alternative reinforcer. Activity was monitored using Actical® activity monitors, as described previously (Andersen et al. 2010, 2012a, 2012b). Actigraphy measures have been used to assess sleep-wake patterns in rhesus macaques (Barrett et al. 2009) and in humans (Ancoli-Israel et al. 2003; Kushida et al. 2001; Sadeh et al. 1995; Sadeh and Acebo 2002) and are considered a valid index of human sleep (Sadeh et al. 1995; Kushida et al. 2001). Further, a recent review indicated that pharmacological and non-pharmacological changes in sleep measures could be detected using actigraphy (Sadeh 2011). Rhesus monkeys are the most extensively studied diurnal nonhuman primates and have features, such as consolidated nighttime sleep, that are similar to humans (Balzamo et al. 1977; Masuda and Zhadanova 2010). Similarities in sleep architecture between rhesus monkeys and humans make them an excellent model for studying human sleep (Daley et al. 2006). We hypothesized that cocaine self-administration would disrupt sleep measures and that sleep disruption would increase the reinforcing strength of cocaine.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Seven individually housed adult (age 16–18) male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) currently trained to respond on a cocaine-food choice paradigm served as subjects. All monkeys had an extensive (> 5 years) history of cocaine self-administration, as well as treatments with the D3/D2 agonist quinpirole and the D1-like agonist SKF 81297 (Hamilton et al. 2010, 2011). Monkeys were weighed weekly and body weights maintained at approximately 95% of free-feeding weights by food earned during experimental sessions and by supplemental feeding of LabDiet Monkey Chow and fresh fruit no sooner than 30 minutes after the session; water was available ad libitum while in the home cage. Each monkey was fitted with an aluminum collar (Model B008, Primate Products, Redwood City, CA) and trained to sit calmly in a standard primate chair (Primate Products). All experimental manipulations were performed in accordance with the 2003 National Research Council Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research and were approved by the Wake Forest University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Environmental enrichment was provided as outlined in the Animal Care and Use Committee of Wake Forest University Nonhuman Primate Environmental Enrichment Plan.

Surgery

Each monkey was prepared with a chronic indwelling venous catheter and subcutaneous vascular port (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL) using aseptic surgical procedures. Anesthesia was induced with dexmedetomidine (0.04 mg/kg, i.m.) and ketamine (5 mg/kg, i.m.) and maintained with ketamine (5 mg/kg, i.m.) as needed. Vital signs were monitored for the duration of the surgery. Briefly, a catheter was inserted into a peripheral vein to the level of the vena cava. The distal end of the catheter was passed subcutaneously to a point slightly off the midline of the back, where an incision was made. The end of the catheter was then attached to the vascular access port and placed in a pocket formed by blunt dissection. Anesthesia was reversed using atipamezole (0.2 mg/kg, i.m.). Prior to each self-administration session, the back of the animal was cleaned with betadine and 95% EtOH, and the port was connected to the infusion pump located outside the chamber via a 22-gauge Huber Point Needle (Access Technologies). The pump was operated for approximately 3 s to fill the port and catheter with saline prior to starting the session. Each port and catheter was filled with heparinized saline solution (100 U/ml) after every experimental session to prolong patency.

Apparatus

The apparatus for operant responding consisted of a ventilated, sound-attenuating chamber (1.5×0.74× 0.76 m; Med Associates, East Fairfield, VT) designed to accommodate a primate chair. Two finger pokes (5 cm wide) were located on one side of the chamber with a horizontal row of three stimulus lights 14 cm above each finger poke and a food receptacle between the response keys. The receptacle was connected with tygon tubing to a pellet dispenser (Gerbarands Corp., Arlington, MA) located on the top of the chamber for delivery of 1-g banana-flavored food pellets (P.K. Noyes Co., Lancaster, NH). An infusion pump (Cole-Palmer, Inc., Chicago, IL) was located on the top of the chamber.

Activity and sleep measures

In order to quantify behavioral indices of sleep all monkeys were fitted with an Actical® (Phillips Respironics, Bend, OR) activity monitor, an omnidirectional accelerometer that measures the subject’s physical activity, secured to the collar. Actigraphy is a non-invasive technique to examine activity and can be used to determine several sleep measures. Of note, sleep measures obtained can only be inferred as a recorded lack of movement. Activity was recorded in 1-min epoch lengths (1440 epochs/day) and the period of activity during the lights-out cycle was quantified. Data were downloaded and analyzed using Actiware Sleep 3.4 (Mini-Matter Co. Inc., Bend, OR) software. The following behavioral indices of sleep were assessed: sleep efficiency (total sleep time as a percentage of the period of time with the lights out [600 min]); sleep latency (latency before the onset of sleep following lights out); and the total activity in the lights out period. For baseline measures we monitored activity for 1 week in the absence of any other behavioral testing (light-dark cycle: 0600-2000). Baseline measures occurred one week prior to the cocaine self-administration experiments.

Experiment 1. Effects of cocaine self-administration on nighttime activity

Initially, activity was monitored each night for 1 week when experimental sessions were not conducted in the mornings and served as “baseline”. For self-administration studies, each morning (~0730), Monday-Friday, monkeys self-administered cocaine under conditions in which food reinforcement was concurrently available (i.e., choice procedure). For these studies, food reinforcement (three, 1.0-gram banana-flavored pellets) was contingent upon completing a fixed-ratio (FR) 30-response requirement on one lever, while cocaine (0.003–0.3 mg/kg per injection) or saline presentation was contingent on responding on the other lever under an FR 30 schedule of reinforcement. Reinforcement was contingent on 30 consecutive responses on a lever and sessions end after 30 total reinforcers or 60 min. Each session began with a forced trial for each reinforcer. Also, following five consecutive same reinforcers there was a forced trial on the opposing finger-poke manipulandum. The cocaine dose remained constant for at least 5 sessions and until choice responding was deemed stable (choice was within 20% of the mean responding for 3 consecutive sessions without trends) before changing the dose. Doses were tested in random order for each monkey. Activity during “lights out” was recorded during this same time period for quantification of sleep measures. Following determination of a cocaine-choice dose-response curve (Figure 1), the lowest preferred dose (i.e., the lowest cocaine dose that engendered ≥ 80% trials on the cocaine-associated lever), based on 3-day means of stable performance, was determined for each monkey.

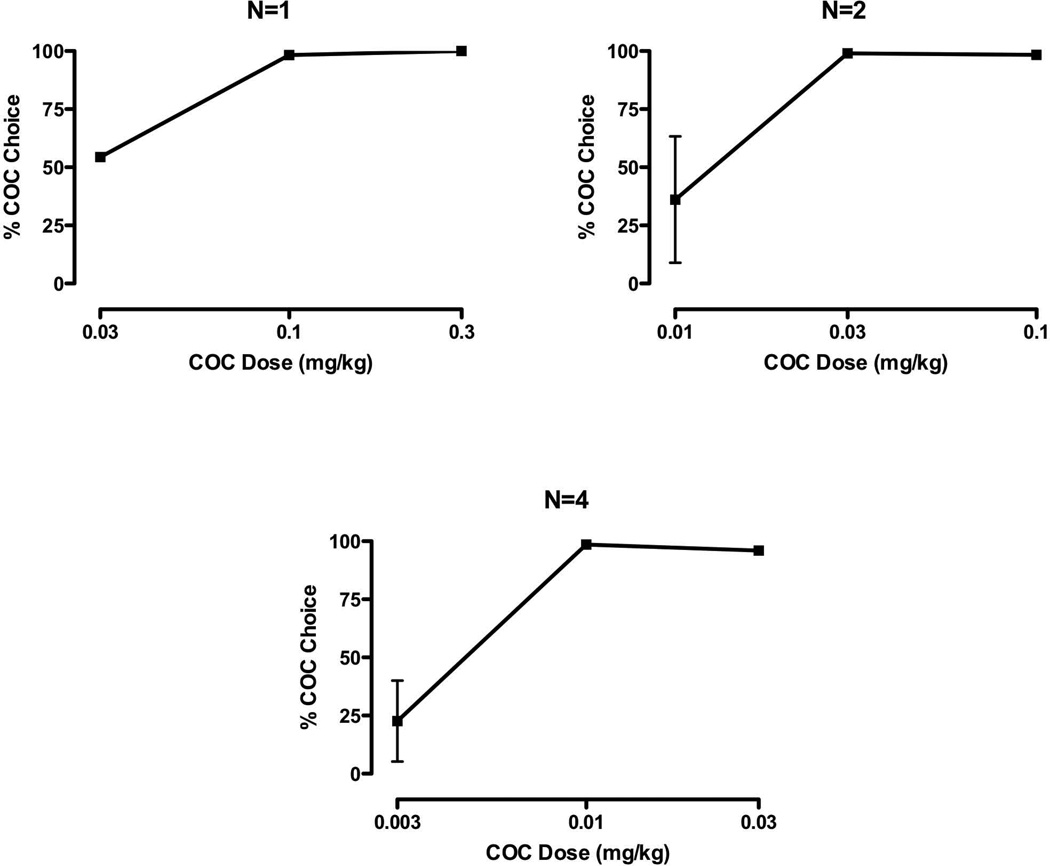

FIGURE 1.

Mean (± SD or SEM) cocaine-choice curves grouped according to the lowest preferred doses: 0.1mg/kg (left panel); 0.03 mg/kg (right panel); and 0.01 mg/kg (bottom panel)

Experiment 2. Effects of sleep disruption on cocaine self-administration

For these studies, the effect of sleep disruption on cocaine self-administration was examined using a half-log unit dose of cocaine below each individual monkey’s preferred cocaine dose. Sleep disruption occurred while the monkey was in their home cage and was achieved by keeping the lights on during the typical lights-out period and by having an investigator (R.E.B.) enter the room hourly to awaken the monkeys by tapping on their cage with a stick. This protocol was designed to disrupt sleep each hour, not to produce sleep deprivation by forcing the monkeys to stay awake all night. On the morning (0730) immediately following a night of sleep disruption, the monkeys were again studied in the cocaine-food choice paradigm and the percentage of cocaine choice was calculated.

Data Analysis

The primary dependent variables were the following behavioral indices of sleep (sleep efficiency, sleep latency, total lights out activity) and the percent of cocaine choice. Changes in sleep measures were analyzed using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA and the percentage of cocaine choice was analyzed using a paired t-test. For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using seven subjects as one monkey lost catheter patency during the study.

Results

Experiment 1. Effects of cocaine self-administration on nighttime activity

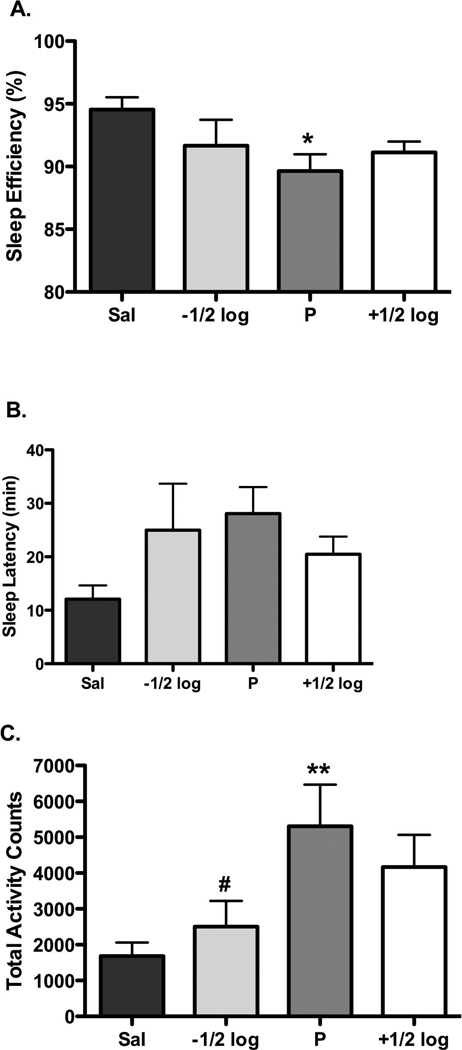

There was individual-subject variability in sensitivity to cocaine when studied under a concurrent schedule of reinforcement, with the lowest preferred dose being 0.01 (n=4), 0.03 (n=2) and 0.1 (n=1) mg/kg (Figure 1). While a dose one-half log-units higher resulted in similar (i.e. >80%) cocaine preference, intake at the higher dose was significantly greater (p<0.05), with mean (± SEM) intakes of 0.83 (0.33) and 1.50 (0.56) mg/kg at the lowest preferred dose and one-half log-unit higher, respectively. Under baseline conditions (i.e. no morning experimental sessions), nighttime activity (beginning at 2000) averaged 2031.6 counts (range 890.3–4008.3), sleep efficiency was approximately 93% (range 88.5–96.7%) and the latency to sleep was approximately 19 min (range 1.5–32.5 min; see Table 1). There were no significant differences between baseline conditions and saline self-administration for activity, sleep efficiency and latency to sleep (Table 1). During the nighttime following self-administration of the preferred dose of cocaine there was a significant decrease in sleep efficiency (p<0.05) and a significant increase in total lights out activity (p<0.01); sleep latency modestly (p=0.1) increased (Figure 2). Sleep efficiency was not influenced by cocaine dose, while total activity was significantly (p<0.05) lower than following the lowest preferred dose, representing an inverted U-shaped function of cocaine dose (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Sleep measures for baseline and saline self-administration (expressed as the average ± SEM) with the ranges in parentheses.

| Baseline | Saline | |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Efficiency (%) | 92.92 ± 1.17 (88.5–96.7 | 94.54 ± 0.98 (89.2–96.8) |

| Sleep Latency (min) | 19.15 ± 4.18 (1.5–32.5) | 12.08 ± 2.56 (4–22.0) |

| Total lights-out Activity Counts | 2031.55 ± 392.70 (890.3–4008.3) | 1684.20 ± 375.72 (740.0–3736.5) |

FIGURE 2.

Mean (± SEM) effect of self-administered saline (dark gray bars) and different cocaine doses on (A) sleep efficiency, (B) sleep latency, and (C) total lights-out activity. *p < 0.05 compared to saline, **p < 0.01 compared to saline; #p<0.05 compared to lowest preferred dose; n=7

Experiment 2. Effects of sleep disruption on cocaine self-administration

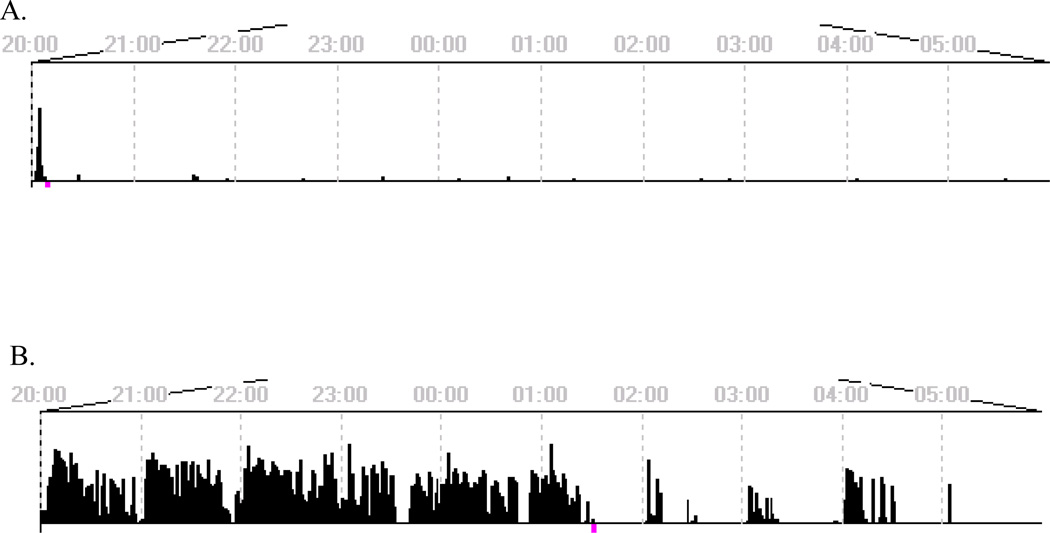

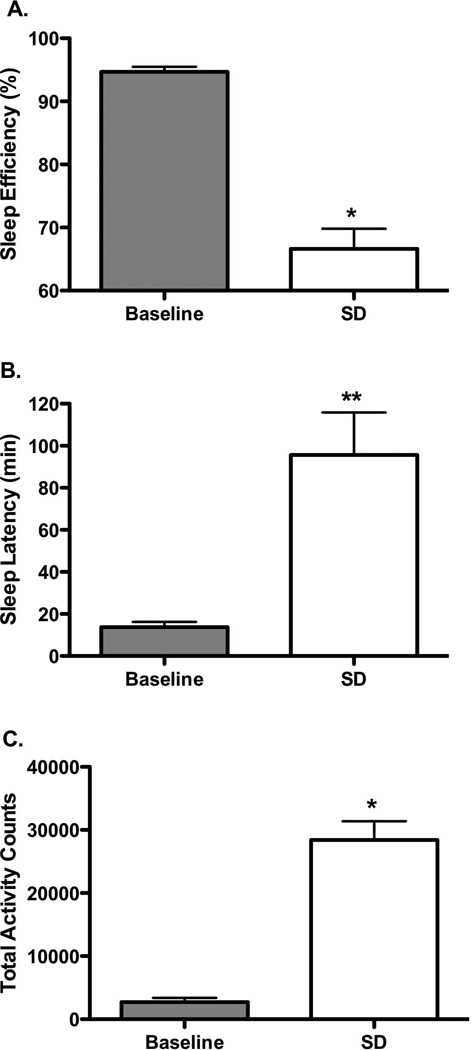

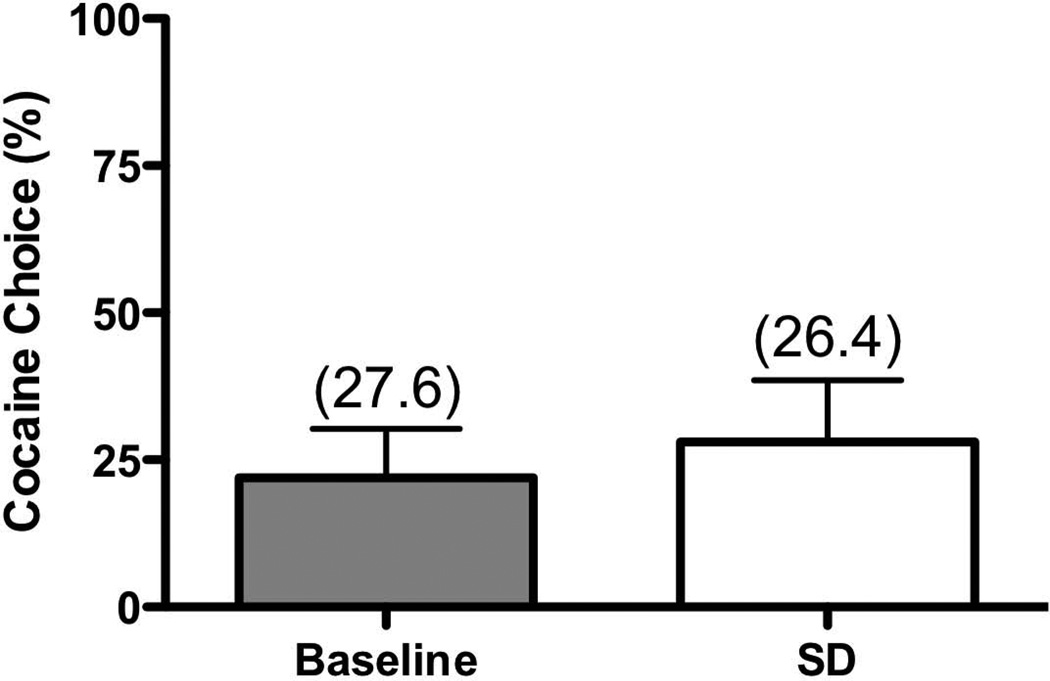

Leaving the lights on and entering the housing room each hour between 2000-0600 significantly affected behavior, as shown in a representative actogram (Figure 3). Sleep disruption decreased sleep efficiency (p<0.0001), and significantly increased sleep latency (p<0.001), and total nighttime activity (p<0.0001) (Figure 4). The consequences of sleep disruption were examined on cocaine self-administration using a dose one-half log-unit below the lowest preferred dose. Following one night of sleep disruption, there were no observed differences (p=0.331) in cocaine preference, nor were the total number of trials significantly affected (Figure 5).

FIGURE 3.

Individual (R-1568) lights-out (2000-0600) actograms showing activity for low-dose cocaine baseline (A) and sleep disruption (B).

FIGURE 4.

Mean (± SEM) sleep measures during baseline cocaine conditions (light gray bars) and following one night of sleep disruption (SD, white bars)): (A) sleep efficiency; (B) sleep latency; and (C) total lights-out activity. *p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01; n=7

FIGURE 5.

Mean (± SEM) percent of cocaine choice for baseline conditions (light gray bars) and following one night of sleep disruption (SD, white bars) with the average total number of trials (out of 30 maximum) in parentheses; n=7

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the relationship between cocaine self-administration and sleep disturbances using actigraphy in adult rhesus monkeys. Behavioral indices of sleep did not differ between baseline conditions (one week of uninterrupted home cage activity) and conditions where the monkeys chose between self-administered saline and food, indicating that the experimental procedure (i.e. removal from home cage, interaction with the investigator and food reinforcement) did not affect nighttime sleep measures. Following cocaine self-administration, monkeys had significantly lower sleep efficiencies while their latency to fall asleep and total lights out activity increased. For latency to sleep and activity, these measures varied as a function of dose in an inverted U-shaped fashion. Finally, when choosing between a low, non-preferred dose of cocaine and food, nighttime sleep disruption did not significantly increase cocaine choice. While these findings suggest that sensitivity to cocaine may not be enhanced by single-night sleep disruption, it remains possible that treating the sleep disturbances following high-dose cocaine self-administration may provide a viable adjunct treatment strategy for cocaine addiction.

To our knowledge, these are the first studies to characterize the effects of cocaine self-administration on nighttime activity in a rhesus monkey model of cocaine abuse. Of particular importance was the observation that these effects were noted at the lowest preferred dose of cocaine and were apparent at least 12 hrs after cocaine self-administration. If the increases in activity and decreases in sleep efficiency were a direct pharmacological mechanism to cocaine reinforcement at 7:30 am, secondary sleep measures obtained following a dose one-half log-unit higher should have shown similar or greater effects relative to the lowest preferred dose. Despite significantly greater intakes at the highest cocaine dose, the effects on behavioral indices of sleep were not greater. This is in contrast to results from a study conducted in rhesus monkeys, in which a single, non-contingent, intramuscular dose of 1.0 mg/kg methamphetamine produced greater nighttime activity than lower methamphetamine doses and disrupted nighttime cooling that was observed out to 18 hours after injection (Crean et al. 2006). Additional research is necessary to elucidate the mechanism by which cocaine self-administration disrupts behavioral indices of sleep in a non dose-dependent manner.

Our results suggest that cocaine self-administration is responsible, either directly or indirectly, for causing some of the observed and reported sleep disturbances described by human cocaine users and are similar to a study conducted in humans where REM sleep was found to be shortest on nights following cocaine use (Morgan et al. 2008). These results are also similar to findings that, following an acute intraperitoneal (i.p.) cocaine injection in rats, the time spent in wakefulness increased and slow-wave sleep decreased in a dose-dependent manner compared to controls (Knapp et al. 2007). The present results in monkeys are also supported by a vast literature showing that the use of stimulant medication is associated with sleep problems. For instance, modafinil, a dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibitor, has been shown to affect the sleep-wake cycle of nonhuman primates (Andersen et al. 2010). These investigators also examined several measures of sleep in rhesus monkeys during chronic treatment with the DAT inhibitor RTI-336 and found significant increases in evening activity, sleep latency and sleep fragmentation, while sleep efficiency was decreased (Andersen et al. 2012b). While actigraphy has been shown to correlate significantly with polysomnography (PSG) (Weiss et al. 2010), it should be noted that these investigators also reported that the correlation between Actical and PSG-determined sleep efficiency was just below significance (r = 0.35, p<0.0598).

The present study also tested the hypothesis that sleep disruption would increase sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of cocaine, providing a potential environmental variable that influenced drug self-administration. To achieve significant disruptions in sleep measures, the lights in the animal housing room were left on all night and a person (R.E.B.) entered the room hourly to awaken the monkeys. This method of sleep disruption was not intended to provide complete sleep deprivation. Although we were able to produce significant disruption in several behavioral indices of sleep, as represented by increases in nighttime activity, no monkey showed increases in the percent of cocaine choice for a dose of cocaine that was one-half log-unit below the preferred dose, in contrast to our hypothesis. One possible explanation for the lack of an effect on the percent of cocaine choice could be a result of the alternative reinforcer (food pellets) that was available. Clinical literature suggests that sleep loss will increase food intake (Brondel et al. 2010), enhance the drive to consume food (Benedict et al. 2012), and that the associated stress of sleep loss may lead to increased hunger and appetite (Pejovic et al. 2010). Thus, the effect of sleep disruption on cocaine choice with a food reinforcer as the competing stimulus may have negated any effect that we had hypothesized. While we examined sleep disruption on low-dose cocaine self-administration, it may be that the higher, reinforcing doses are more vulnerable to sleep disturbances. Thus, another limitation of the present choice paradigm is that intake for the lowest preferred dose could not be substantially increased if we had tested sleep disruption when that dose was available. Future studies will need to be conducted to more thoroughly examine the relationship between sleep disruption and the consequences on cocaine self-administration.

Sleep has been described as a dynamic activity that is as essential to good health as diet and exercise and as necessary for survival as food and water (National Sleep Foundation 2006). While there appears to be a clear link between sleep problems and substance abuse, there is limited research examining this relationship. It has been shown that one night of sleep loss led to increased impulsivity toward negative stimuli (Anderson and Platten 2011) and impulsiveness is a trait associated with an increased likelihood to self-administer drugs of abuse (Moeller et al. 2001; Perry et al. 2005). Further, a study conducted in adolescents found that those who had more sleep problems were more likely to abuse drugs (Fakier and Wild 2011). Also, a study examining the associations between weekend-weekday shifts in sleep timing and the neural response to monetary reward in healthy adolescents led the authors to hypothesize that the circadian misalignment associated with weekend shifts in sleep timing may contribute to reward-related problems, including substance abuse (Hasler et al. 2012). Since substance abuse and insomnia are two major health concerns in the U.S., elucidating the relationship between these two disorders may help in the search for effective treatment strategies aimed at both conditions. While there is a disconnect between cocaine-induced effects on behavioral indices of sleep and the effects of sleep disruption on low-dose cocaine reinforcement, it remains to be determined if treating an individual’s sleep disturbances following high doses of cocaine could be a potential treatment strategy for cocaine addiction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Tonya Calhoun and Michael Coller for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Kevin Murnane for assistance with analysis of sleep measures. This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA025120.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.E.B. and M.A.N. designed the experiments. R.E.B. performed the behavioral studies, and analyzed the data. The manuscript was written by R.E.B. and M.A.N.

REFERENCES

- Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ML, Diaz MP, Murnane KS, Howell LL. Effects of methamphetamine self-administration on actigraphy-based sleep parameters in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2012a doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2943-2. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ML, Kessler E, Murnane KS, McClung JC, Tufik S, Howell LL. Dopamine transporter-related effects of modafinil in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1839-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ML, Sawyer EK, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Influence of chronic dopamine transporter inhibition by RTI-336 on motor behavior, sleep, and hormone levels in rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012b;20:77–83. doi: 10.1037/a0026034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Platten CR. Sleep deprivation lowers inhibition and enhances impulsivity to negative stimuli. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:463–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzamo E, Santucci V, Seri B, Vuillon-Cacciuttolo G, Bert J. Nonhuman primates: laboratory animals of choice for neurophysiological studies of sleep. Lab Anim Sci. 1977;27:879–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkoukis TJ, Avidan AY, editors. Review of Sleep Medicine. 2nd edn. Pennsylvania: Butterworth-Hinemann; 2007. pp. 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CE, Noble P, Hanson E, Pine DS, Winslow JT, Nelson EE. Early adverse rearing experiences alter sleep-wake patterns and plasma cortisol levels in juvenile rhesus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict C, Brooks SJ, O’Daly OG, Almen MS, Morell A, Aberg K, Gingnell M, Schultes B, Hallschmid M, Broman JE, Larsson EM, Schioth HB. Acute sleep deprivation enhances the brain’s response to hedonic food stimuli: an fMRI study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E443–E447. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Koob GF. What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications. Sleep. 2004;27:1181–1194. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondel L, Romer MA, Nougues PM, Touyarou P, Davenne D. Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1550–1559. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Robinson EA, Zucker RA, Greden JF. Insomnia, self-medication, and relapse to alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:399–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 14 Dec 2012];2012 http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/economics/econ_facts/.

- Clark CP, Gillin JC, Golshan S, Demodena A, Smith TL, Danowski S, Irwin M, Schuckit M. Increased REM sleep density at admission predicts relapse by three months in primary alcoholics with a lifetime diagnosis of secondary depression. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43:601–607. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean RD, Davis SA, Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Katner SN, Taffe MA. Effects of (±)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, (±)3,4-methylenedixoyamphetamine and amphetamine on temperature and activity in rhesus macaques. Neuroscience. 2006;142:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JT, Turner RS, Freeman A, Bliwise DL, Rye DB. Prolonged assessment of sleep and daytime sleepiness in unrestrained Macaca mulatta. Sleep. 2006;29:221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinsin ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, Pena Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SP, Gillin JC, Smith TL, DeModena A. The sleep of abstinent pure primary alcoholic patients: natural course and relationship to relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1796–1802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakier N, Wild LG. Associations among sleep problems, learning difficulties and substance use in adolescence. J Adolesc. 2011;34:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JH, Peters TJ. Impaired sleep in alcohol misusers and dependent alcoholics and the impact upon outcome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1044–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillin JC, Smith TL, Irwin M, Butters N, Demodena A, Schuckit M. Increased pressure for rapid eye movement sleep at time of hospital admission predicts relapse in nondepressed patients with primary alcoholism at 3-month follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:189–197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LR, Czoty PW, Gage HD, Nader MA. Characterization of the dopamine receptor system in adult rhesus monkeys exposed to cocaine throughout gestation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1847-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LR, Czoty PW, Nader MA. Behavioral characterization of adult male and female rhesus monkeys exposed to cocaine throughout gestation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:799–808. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2038-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H. Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. Report prepared by The Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Based on estimates, analyses, and data reported in Harwood, H.; Fountain, D.; and Livermore, G. The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse in the United States 1992. Report prepared for the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. NIH Publication No. 98-4327. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Holm SM, Jakubcak JL, Silk JS, Ryan ND, Phillips ML, Dahl RE, Forbes EE. Weekend-weekday advances in sleep timing are associated with altered reward-related brain function in healthy adolescents. Biol Psychol. 2012;91:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp CM, Datta S, Ciraulo DA, Kornetsky C. Effects of low dose cocaine on REM sleep in the freely moving rat. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2007;5:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2006.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disoriented patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolt HP, Gillin JC. Sleep abnormalities during abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients. Aetiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:413–425. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Broft A, Foltin RW, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Perez A, Frankle WG, Cooper T, Kleber HD, Fischman MW, Laruelle M. Cocaine dependence and D2 receptor availability in the functional subdivisions of the striatum: Relationship with cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1190–1202. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K, Zhadanova IV. Intrinsic activity rhythms in Macaca mulatta: their entrainment to light and melatonin. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25:361–371. doi: 10.1177/0748730410379382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Grant KA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Kaplan JR, Prioleau O, Nader SH, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer RL, Nader MA. Social Dominance in monkeys: dopamine D2 receptors and cocaine self-administration. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/nn798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PT, Pace-Schott EF, Sahul ZH, Coric V, Stickgold R, Malison RT. Sleep, sleep-dependent procedural learning and vigilance in chronic cocaine users: Evidence for occult insomnia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PT, Pace-Schott EF, Sahul ZH, Coric V, Stickgold R, Malison RT. Sleep architecture, cocaine and visual learning. Addiction. 2008;103:1344–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Morgan D, Gage HD, Nader SH, Calhoun TL, Buchheimer N, et al. PET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors during chronic cocaine self-administration in monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1050–1056. doi: 10.1038/nn1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. [Accessed 14 Dec 2012];Cocaine: Abuse and Addiction. 2010 http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine-abuse-addiction.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Center on Sleep Disorders Research. [Accessed 8 Nov 2012];National sleep disorders research plan. 2003 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/sleep/res_plan/sleep-rplan.pdf.

- National Sleep Foundation (NSF) Sleep-wake cycle: its physiology and impact on health. Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pejovic S, Vgontzas AN, Basta M, Tsaoussoglou M, Zoumakis E, Vgontzas A, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Leptin and hunger levels in young healthy adults after one night of sleep loss. J Sleep Res. 2010;19:552–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Larson EB, German JP, Madden GJ, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl MD, Fang J, Grigson PS. Acute sleep deprivation increases the rate and efficiency of cocaine self-administration, but not the perceived value of cocaine reward in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;94:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A. the role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: an update. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Acebo C. The role of actigraphy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:113–124. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Hauri PJ, Kripke DF, Lavie P. The role of actigraphy in the evaluation of sleep disorders. Sleep. 1995;18:288–302. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center. [Accessed 14 Dec 2012];National Drug Threat Assessment. 2010 www.justice.gov/ndic/pubs38/38661/index.htm.

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schlyer DJ, et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1993;14:169–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Benveniste H, Kim R, Thanos PK, Ferre S. Evidence that sleep deprivation downregulates dopamine D2R in ventral striatum in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6711–6717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0045-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, et al. Prediction of reinforcing responses to psychostimulants in humans by brain D2 dopamine receptors. Am J Psych. 1999;156:1440–1443. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Wong C, Ma J, Pradhan K, Tomasi D, Thanos PK, Ferre S, Jayne M. Sleep deprivation decreases binding of [11C] raclopride to dopamine D2/D3 receptors in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8454–8461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AR, Johnson NL, Berger NA, Redline S. Validity of activity-based devices to estimate sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:336–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]