Abstract

Objectives

In December 2009, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that women under 21 years old should not receive cervical cancer screening (Pap tests) or HPV tests. This study examined whether clinicians stopped administering Pap and HPV tests among women less than 21 years of age after new ACOG guidelines were issued.

Study Design

This study was a retrospective secondary data analysis of administrative claims data that included insurance enrollees from across the US that examined the frequency of Pap tests and HPV tests among 178,898 non-immunocompromised females 12–20 years old who had a paid claim for a well-woman visit in 2008, 2009, or 2010. Young women with well-woman exams in each observed year were examined longitudinally to determine whether past diagnoses of cervical cell abnormalities accounted for Pap testing in 2010.

Results

The proportion of women less than 21 years old that received a Pap test as part of her well-woman exam dropped from 77% in 2008 and 2009 to 57% by December of 2010, while HPV testing remained stable across time. A diagnosis of cervical cell abnormalities in 2009 was associated with Pap testing in 2010. However, a previous Pap test was more strongly associated with a Pap test in 2010.

Conclusions

These data show that some physicians are adjusting their practices among young women according to ACOG guidelines, but Pap and HPV testing among insured women less than 21 years of age still remains unnecessarily high.

Keywords: Pap test, HPV test, human papillomavirus, guidelines compliance

Background

In 2009, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that Papanicolaou (Pap) and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing not be performed in young women before they reach 21 years of age.1 Previous guidelines recommended that young women should receive a Pap test 3 years after sexual initiation, or at age 21, whichever came first.2 New recommendations in 2009 were made because precancerous cervical cells have been found to regress more often among adolescents compared to adult women with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) I, and CIN II regressing among young women in most cases within 6 months to 3 years.3–5 Thus, use of Pap tests in this population may lead to unnecessary treatment of conditions that would spontaneously resolve if left untreated. Furthermore, there is evidence that some procedures used to treat precancerous lesions may lead to long term problems such as low birth weight infants, preterm premature rupture of the membranes, and difficulties with carrying a pregnancy fully to term.6–12 Diagnosis of a precancerous lesion or sexually transmitted infection, such as HPV, may also cause unnecessary psychological distress and increased concern among teenage patients.13–16

ACOG also recommends that if a Pap test has previously been done and low-grade abnormalities have been detected, conservative observational management should be the course of action among young women, with annual Pap tests to monitor possible progression.17 For adolescents with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), colposcopic evaluation with endocervical assessment is recommended every 6 months if they have not been diagnosed with CIN II or III by biopsy.1, 17 An excisional diagnostic procedure should only be performed for HSIL that persists for at least 24 months.17 In addition, guidelines state that HPV tests should not be administered in women <21 years old. However, if HPV tests are inadvertently performed in this group, the results should not affect management since HPV infections are common in young women, and may not cause the development of HSIL.1

Although the recommendations regarding initiation of Pap testing were published almost 3 years ago, it is unknown to what extent physicians are adhering to these new guidelines. The purpose of this study was to determine whether physicians adopted ACOG Pap testing and HPV testing guidelines in females <21 years of age. We also examined whether inappropriate Pap testing in 2010 resulted from previous diagnoses of cervical cell abnormalities among females (<21 in 2010) who had well-woman exams during each of the three years of the study.

Methods

For this study, we used administrative claims records from a private health insurance provider with plans available across the US. The dataset that was used represents more than 45 million individuals who were enrolled between 2000 and 2010, and who had at least one medical claim. Records were obtained from a claims dataset called Clinformatics for DataMart affiliated with OptumInsight. Demographic and socioeconomic information were not available for individual enrollees in this dataset.18 These records were examined for females that had well-woman exams between 2008 and 2010. A total of 179,684 individual cases were identified who had a well-woman exam using the International Classification of Diseases-9th edition (ICD-9) code V72.31, and who were between 12 and 20 years old during the year their exam occurred. Of these females, 786 had an ICD-9 code indicating they were immunocompromised, or had conditions that are associated with a compromised immune system, including: HIV positive, immune deficiencies, leukocytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, and neutropenia, (ICD-9 codes 042, 043, 044, V08, 795.71, 279.3, 279.0, 279.1, 279.2, 288.50, 288.4, 288.00, 288.5, 288.09; Figure 1). Immunocompromised cases were excluded from further analyses because ACOG recommends that these individuals should be screened for cervical cancer at a younger age due to their increased risk of developing malignancies. The remaining 178,898 females had a total of 221,580 well-woman encounters between 2008 and 2010. The University of Texas Institutional Review Board exempted this study from full review.

Figure 1.

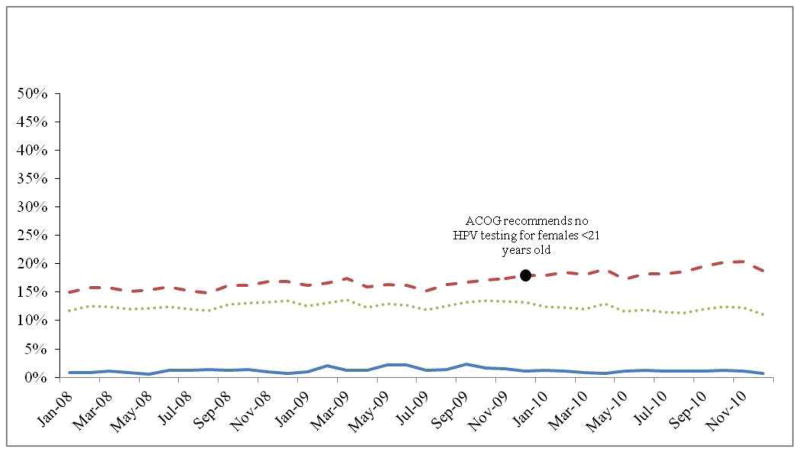

Proportion of young women who received Pap tests (2008–2010)

Description: The proportion of young women (<21 years old) who had a Pap test during their well-woman exam was examined each month between 2008–2010. The red dot indicates the month when ACOG issued new guidelines recommending that healthcare providers stop giving Pap tests to women <21 years of age.

ICD-9, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for Pap smears (V72.32, V76.2, V76.47, P3000, G0123, G0124, G0141, G0143, G0144, G0145, 88141–88143, 88147, 88148, 88155, 88164, 88165, and 88174) indicated the receipt of a Pap smear among females who had a record of a well-woman exam. HPV testing was identified using an ICD-9 code (V73.81) and CPT codes (87620–87622). Colposcopies, (CPT codes 56820, 56821, 57420, 57421, 57452, 47454, 57455, 57456, 57460, 57461)and conizations (CPT code 57520), or loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP; CPT codes 57460, 57522, 57461) were also examined. To determine the occurrence of cervical dysplasia and other related conditions among the subjects in this study, ICD-9 codes indicating that they had the following conditions were examined: high grade HPV DNA (795.05), atypical glandular cells (795.00), cervical dysplasia (633.10), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS; 795.01), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, cannot exclude high grade (ASCH; 795.02), LSIL (795.03), HSIL (795.04), CIN I-III (622.11, 622.12, 233.1), and malignant neoplasm of the cervix (180.1, 180.8).

Statistical Analyses

The proportion of young females who received a Pap smear, HPV DNA test, colposcopy, or conization/LEEP as part of their well-woman exam was examined for 2008, 2009, and 2010. Fisher’s exact tests were used for one-way comparisons of reductions in Pap tests, HPV tests, colposcopy procedures, conizations/LEEPs, and diagnoses of cervical cell abnormalities between 2008 and 2009 as well as between 2009 and 2010. These tests were used to determine whether proportions in subsequent years were significantly lower than in the previous year.

The proportion of females who had an ICD-9 diagnosis for the following conditions as part of their well-woman exam, and as a result of a Pap test during the respective year was also determined: high-risk HPV DNA, those with any diagnosis of abnormal cervical cells, atypical glandular cells, cervical dysplasia, ASCUS, ASCH, LSIL, HSIL, CIN I-CIN III, and malignant neoplasm of the cervix. The proportion of females who received a Pap smear as part of their well-woman exam was plotted across time by month. The proportion of young women who received an HPV test, an HPV test and a Pap test, as well as an HPV test without a Pap test were plotted by month for the three years included in the study. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used to examine the association between a previous diagnosis of cervical cell abnormalities and a Pap test in 2010 among young females who had a well-woman exam in 2008, 2009, and 2010 (n=5,294). This model controlled for age in 2010, having a Pap test in 2008 or 2009, HPV test given in 2008 or 2009, and the presence of high-risk HPV DNA in 2008 or 2009.

Results

The mean age of young women in the 2008 sample was 18.4 years, and was 18.5 years old in both 2009 and 2010. Age distribution was the same for each year of observation, where 5% of the sample was 12–15 years, 25% was <18 years, and 50% were 19–20 years old. These young women lived in the U.S. with a higher proportion living in the South, followed by the Midwest, Southwest, and Mid-Atlantic states (TABLE 1). Providers working at a facility, such as a hospital or clinic, provided the majority of the well-woman exams that were included in the dataset. The proportion of young women who received Pap tests, colposcopies, or conization/LEEPs decreased between 2008 and 2009, and again between 2009 and 2010. An increase in the number of HPV tests performed was observed between 2008 and 2009 (p<0.01). However, after ACOG guidelines were issued at the end of 2009, a decrease in HPV tests between 2009 and 2010 as a proportion of women who received well-woman exams was observed.

Table 1.

Women (12–20 years old during year of treatment) who had a well-woman exam, Papanicolaou test, HPV test, or conization/LEEP procedure in 2008, 2009, or 2010

| n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of participants who had a well-woman exam (n=178,898)1 | |||||

| Northeast | 6,815 (3.8) | ||||

| Mid Atlantic | 18,622 (10.4) | ||||

| Midwest | 45,798 (25.6) | ||||

| South | 61,318 (34.3) | ||||

| Southwest | 30,619 (17.1) | ||||

| West | 15,726 (8.8) | ||||

| Provider type for well-woman exams that were recorded (n=221,580) | |||||

| Obstetrician/Gynecologist | 10,560 (7.6) | ||||

| Family practitioner | 7,891 (4.9) | ||||

| Nurse practitioner | 727 (0.4) | ||||

| Specialist | 26,286 (16.4) | ||||

| Facility | 113,967 (71.3) | ||||

| Other | 464 (0.3) | ||||

| Unknown | 61,685 | ||||

| Year that Procedure was performed: | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | ||

| Procedure | n (%) | n (%) | p-value2 | n (%) | p-value3 |

|

|

|||||

| Well Woman Exam | 79,776 | 76,885 | 64,919 | ||

| Papanicolaou test | 61,922 (77.6) | 57,927 (75.3) | p<0.001 | 40,018 (61.6) | p<0.001 |

| HPV test | 9,930 (12.4) | 9,879 (12.8) | p=0.98 | 7,719 (11.9) | p<0.001 |

| Colposcopies | 1,631 (2.0) | 1,480 (1.9) | p=0.05 | 1,037 (1.6) | p<0.001 |

| Conization/LEEP | 390 (0.5) | 260 (0.3) | p<0.001 | 118 (0.2) | p<0.001 |

Northeast= CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT; Mid Atlantic= DC, DE, MD, NJ, NY, PA; Midwest= IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI; South= AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV; Southwest= AZ, NM, OK, TX; West= AK, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY

Comparison made using Fisher’s Exact one-way comparison to determine decrease in each procedure between 2008 and 2009

Comparison made using Fisher’s Exact one-way comparison to determine decrease in each procedure between 2009 and 2010

Analyses also tested whether HPV tests, colposcopies, and conization/LEEPs decreased as a proportion of women who also received Pap tests. Chi-square analyses revealed that there were no significant differences in the proportion of colposcopies that were received among women who also had a Pap test (p>0.05). A decrease in conizations/LEEPs between 2008 and 2009 (p<0.001) and between 2009 and 2010 (p<0.001) among those who also received Pap tests was observed.

Two percent of young females who had well-woman exams received a diagnosis of high-risk HPV DNA during each year of the study (TABLE 2). Of females who had a HPV test during the current or previous year, 12% were diagnosed with high risk HPV DNA in 2009 and 11% were diagnosed in 2010. Among the entire sample, the proportion of young women with a diagnosis of any type of cervical cell abnormalities decreased between 2008 and 2010 (p<0.001). However, among young women who received a Pap test, the proportion who received a diagnosis of any type of cervical cell abnormalities remained stable between 2008 and 2009 (p>0.05) and increased between 2009 and 2010 (p<0.01). Of those who received a Pap test, a small proportion was diagnosed with CIN III in the observation period. In this data, there was one diagnosis code for a malignant neoplasm between 2008 and 2010, but upon further investigation of that case, the diagnosis could not be confirmed because there were no follow-up codes that would indicate treatment of a malignancy.

Table 2.

Proportion of women (12–20 years during respective year) with diagnoses related to abnormal cervical cell growth

| Any diagnosed with well- woman exam in 2008, n (%) | Diagnosed with Pap tests during 2008, n (%) | Any diagnosed with well- woman exam in 2009, n (%) | Diagnosed with Pap tests during 2009, n (%) | Any diagnosed with well- woman exam in 2010, n (%) | Diagnosed with Pap tests during 2010, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| High risk HPV DNA | 1,584 (2.0) | 1,509 (2.0) | 1,181 (1.8) | |||

| Abnormal cervical cells | 10,701 (13.4) | 10,157 (16.4) | 9,704 (12.6) | 9,257 (16.0) | 7,038 (10.8) | 6,689 (16.7) |

| Atypical glandular cells, endocervicals, endometrials (Excludes CIN, SIL, CIS, CA) | 2,499 (3.1) | 2,347 (3.8) | 1,939 (2.5) | 1,825 (3.2) | 1,368 (2.1) | 1,288 (3.2) |

| Cervical Dysplasia | 1,167 (1.5) | 1,100 (1.8) | 823 (1.1) | 777 (1.3) | 540 (0.8) | 504 (1.3) |

| ASC-US | 5,339 (6.7) | 5,177 (8.4) | 4,832 (6.3) | 4,687 (8.1) | 3,590 (5.5) | 3,475 (8.7) |

| ASC-H | 661 (0.8) | 625 (1.0) | 573 (0.8) | 539 (0.9) | 374 (0.6) | 351 (0.9) |

| LSIL | 4,347 (5.4) | 4,141 (6.7) | 4,031 (5.2) | 3,880 (6.7) | 2,879 (4.4) | 2,751 (6.9) |

| HSIL | 373 (0.5) | 354 (0.6) | 281 (0.4) | 264 (0.5) | 181 (0.3) | 169 (0.4) |

| CIN I | 2,432 (3.0) | 2,313 (3.7) | 1,898 (2.5) | 1,806 (3.1) | 1,270 (2.0) | 1,202 (3.0) |

| CIN II | 633 (0.8) | 608 (1.0) | 452 (0.6) | 425 (0.7) | 240 (0.4) | 229 (0.6) |

| CIN III | 207 (0.3) | 198 (0.3) | 158 (0.2) | 144 (0.3) | 81 (0.1) | 79 (0.2) |

| Malignant neoplasm of cervix | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

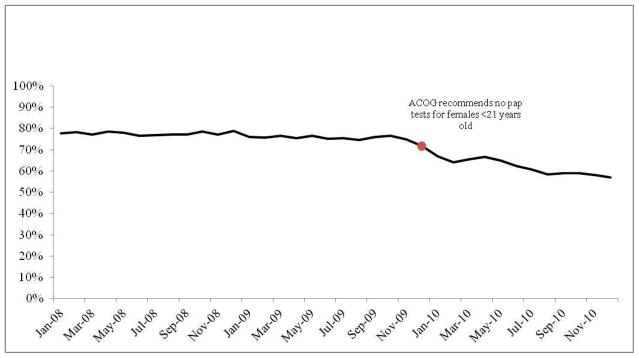

The proportion of females who received a Pap smear as part of their well-woman exam remained stable between January 2008 and October 2009, when the proportion began to decrease (FIGURE 1). In December 2010, the proportion of the sample who received a Pap smear had dropped to 57%, compared to an average of 76.8% who received a Pap smear as part of their well-woman visit between January of 2008 and October of 2009. The proportion of cases who received an HPV test out of those who received a Pap test increased in frequency between 2008 (mean=16%) and 2009 (mean=17%; p<0.001) as well as between 2009 and 2010 (mean=19.3%; p<0.001) (FIGURE 2), and increased compared to the proportion who received an HPV test among the entire sample. The proportion that received an HPV test, but not a Pap smear, was low across all years examined (mean=1.2%, range 0.71–2.37%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of young women who received human papillomavirus (HPV) tests (2008–2010)

Description: The proportion of young women (<21 years old) who had a HPV test during their well-woman exam was examined each month between 2008–2010. The proportion who received both a Pap test and a HPV test, as well as the proportion who only received a HPV test were also examined, and the red dot indicates the month when ACOG issued guidelines recommending that healthcare providers stop giving Pap tests to women <21 years of age, and to stop giving HPV tests to women <30 years of age.

Proportion who received HPV test among those who did not receive Pap test

Proportion who received HPV test among those who did not receive Pap test

Proportion who received HPV test among those who received Pap test

Proportion who received HPV test among those who received Pap test

Proportion who received HPV test among those who had a Well Women exam

Proportion who received HPV test among those who had a Well Women exam

Among young women who had a well-woman exam in 2008, 2009, and 2010 (n=5,310), the diagnosis of abnormal cervical cells in 2009 was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving a Pap test in 2010 (TABLE 3). Females with a diagnosis of abnormal cervical cells in 2008, however, were not more likely to receive a Pap test than those who had not had a diagnosis of abnormal cervical cells. Females who had previously received a Pap smear in 2008 or 2009 were more likely to receive a Pap smear in 2010 than those who had not previously received a Pap smear. Young females were also more likely to have had a Pap smear in 2010 if they had been tested for HPV in 2008 or 2009, but were not more likely to have a Pap smear in 2010 if they had been diagnosed with a high-risk HPV DNA type.

Table 3.

Logistic regression describing the odds of receiving a Pap smear in 2010 among young women (<21 years old) who had a well-woman exam in 2008, 2009, and 2010 (n=5,294)

| OR (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|

| Age in 2010 | 1.15 (1.07–1.23) |

| Pap test in 2008 or 2009 | 13.82 (11.38–16.78) |

| Tested for HPV in 2008 or 2009 | 1.65 (1.31–2.07) |

| High-risk HPV DNA detected, 2008 or 2009 | 1.79 (0.94–3.40) |

| Abnormal cervical cells, 2008 | 0.98 (0.72–1.35) |

| Abnormal cervical cells, 2009 | 1.54 (1.16–2.03) |

Comment

Our findings show that a high proportion of insured young females (<21 years of age) are still receiving Pap tests and HPV tests as part of their well-woman exams, even though ACOG guidelines state that they are not needed. Further, diagnoses of cervical cell abnormalities in 2009 were only weakly associated with Pap testing in 2010, while previous Pap tests were strongly associated with 2010 Pap tests. In contrast to the declining proportion of Pap tests that were performed in 2010, the proportion of young women who received HPV testing remained steady across time. Moreover, HPV testing actually increased among young females who received a Pap smear. Inappropriate HPV testing has been found to be common among providers that offer cervical cancer screening, including 60% of health care providers who admitted to co-testing for HPV among women <30 years old in another study.19 It is unknown why HPV testing was performed among these young women, as it has never been recommended for by ACOG for those <21 years old, with the possible exception of those diagnosed with ASCUS, according to early guidelines.2 These high rates of inappropriate screening increase the costs of healthcare, as well as increase the risk of causing psychological distress among young female patients.13–15

A decrease in colposcopies was observed among young women between 2008 and 2010, although it was not significant among those who also had a Pap test. This indicates that Pap tests may lead to further diagnostic tests among young women. However, our results also demonstrated a decrease in the proportion of young women who received a conization or LEEP across the observed time period, including those who also received Pap testing. This was an encouraging finding as the main purpose of the new ACOG recommendation was to reduce the number of potentially harmful procedures performed on young women. This finding also suggests that although providers may still be performing Pap tests on young women, they are taking a more conservative approach when they discover abnormal findings, since cervical cell abnormalities were observed to be similar between 2008 and 2009 and even increased between 2009 and 2010. As the proportion of women <21 years old who receive Pap testing continues to decline over time, it is likely that the number of invasive follow-up procedures will continue to decrease among women <21 years old. This will the reduce risk to the patient and result in substantial financial savings for the healthcare system.

The proportion of young women diagnosed with LSIL and HSIL in this study was similar to a prior study of 10,090 adolescents (≤18 years old) where 5.7% of adolescents were diagnosed with LSIL and 0.7% were diagnosed with HSIL, 20 compared to 6.7% and 0.6% respectively during 2008 in our study. Our results also confirmed that CIN III is rare among females <21 years old, and malignant neoplasms of the cervix were extremely rare in this age group, similar to the results from other studies.4, 21–23 In this dataset, codes for malignant neoplasm of the cervix was found in only 1 of the 178,899 non-immunocompromised females <21 years of age who had a well-woman exam between 2008 and 2010. Upon further review of diagnosis codes for this patient, it appeared that this case may have been miscoded, because there was no evidence of a biopsy or treatment procedures that would have confirmed and treated a malignancy. Further, later Pap tests indicated regression to LSIL and abnormal glandular cells, although no colposcopy or biopsy was found in the insurance claims for that case.

Among young women with a claim for a well-woman exam in 2008, 2009, and 2010, receiving a Pap test in a previous year had the strongest association with receiving a Pap smear in 2010, even over a previous diagnosis of cervical cell abnormalities. A previous diagnosis of cervical cell abnormalities should be more highly associated with subsequent Pap tests after ACOG guidelines were issued, because those patients would be at higher risk of developing advanced lesions. Although it is unknown why previous Pap testing is most strongly associated with subsequent Pap testing in this sample, yearly visits for birth control may play a role since some facilities still require a Pap test before prescribing birth control.24 Further, young women may requestPap tests without understanding what the test evaluates. Thus, patient expectation could be playing a role in the receipt of Pap testing in young women.24 Whatever the reason for the continued high rates of Pap testing in young women, this study indicates that it is not entirely due to previously diagnosed cervical cell abnormalities among patients who have yearly well-woman exams.

The results from this study highlight that adoption of clinical practices based on new guidelines can be slow which can result in significant costs to insurers and patients in time, money, and psychological stress. It is unclear whether patient knowledge and requests, physician knowledge, or motivation to change are drivers in cervical cancer screening. It is critical to determine why health providers are not following broad ranging clinical recommendations, such as those issued by ACOG. It would be enlightening to understand the role of advertising of diagnostic tests to physicians, conflicting guidelines by different clinical authorities, lack of clinician knowledge, and patient request in the application of inappropriate HPV diagnostic testing in adolescents. Determining reasons for clinicians’ decisions to follow professional guidelines through further research is important for delivery of optimal health care.

Our study had some limitations. We limited our analyses to enrollees of the insurance company that administers the claims data and who had a well-woman visit so we cannot comment on frequency of Pap or HPV tests among young women without a claim for a well-woman exam. Therefore, it is possible that Pap tests and HPV tests may occur more or less frequently among women <21 years old who consult with their provider for other reasons. We also cannot determine why some health providers did not comply with ACOG guidelines. Further, the insurance claims dataset does not contain any socioeconomic or demographic characteristics, so it is difficult to know whether there is related bias that could change the findings. Finally, the logistic regression models only included young women that had previously had a well-woman exam, and may not have been representative of young patients who were enrolled only in 2010, or had their first well-woman exam in 2010. Despite these limitations, this study was able to examine data that is based on actual patient visits that occurred across the US.

In early 2012, USPSTF and American Cancer Society joined ACOG in recommending that cervical cancer screening should not be performed in most patients under age 21. It is possible that many of the physicians who continued to administer Pap tests to females <21 years old ascribe to recommendations from other organizations and will now adjust their practices accordingly. If so, research on insurance claims records after these guidelines were adopted by other associations should show a further reduction in the proportion of young women who receive Pap tests and HPV tests as part of their well-woman exam.

Acknowledgments

Federal support for this study was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) as follows: Dr. Hirth is currently supported by ORWH (NICHD K12HD052023, PI: Berenson) and was supported at the time of initial submission by the NICHD through an institutional training grant (National Research Service Award T32HD055163, PI: Berenson); Dr. Berenson, under a mid-career investigator award in patient-oriented research (K24HD043659, PI: Berenson). This study also was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, which is partially funded by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR029876) from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The findings for this paper were presented at the 140th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in San Francisco, CA. October 27–31, 2012.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jacqueline M. HIRTH, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Women’s Health, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Alai TAN, Department of Preventive Medicine and Community Health, Senior Biostatistician, Sealy Center on Aging, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Gregg S. WILKINSON, Department of Preventive Medicine and Community Health, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Abbey B. BERENSON, Email: abberens@utmb.edu, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Director, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Women’s Health, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd Rte 0587, Galveston, TX 77573, Phone: 409-772-2417, Fax: 409-747-5129.

References

- 1.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin no109: Cervical cytology screening. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114(6):1409–1420. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG Committee on Practice. ACOG practice bulletin clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102(2):417–427. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscicki A-B, Ma Y, Wibbelsman C, et al. Rate of and risks for regression of CIN-2 in adolescents and young women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(6):1373–1380. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fe777f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscicki A-B, Shiboski S, Hills NK, et al. Regression of low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesians in young women. Lancet. 2004;364:1678–1683. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore K, Cofer A, Elliot L, Lanneau G, Walker J, Gold MA. Adolescent cervical dysplasia: histologic evaluation, treatment, and outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197:141.e141–141.e146. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadler L, Saftlas A. Cervical surgery and preterm birth. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2007 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadler L, Saftlas A, Wang W, Exeter M, Whittaker J, McCowan L. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2100–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruinsma FJ, Quinn MA. The risk of preterm birth following treatment for precancerous changes in the cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118:1031–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armarnik S, Sheiner E, Piura B, Meirovitz M, Zlotnik A, Levy A. Obstetric outcome following cervical conization. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2011;283:765–769. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nam KH, Kwon JY, Kim Y-H, Park Y-W. Pregnancy outcome after cervical conization: risk factors for preterm delivery and the efficacy of prophylactic cerclage. Journal of Gynecological Oncology. 2010;21:225–229. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.4.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortoft G, Henriksen TB, Hansen ES, Petersen LK. After conisation of the cervix, the perinatal mortality as a result of preterm delivery increases in subsequent pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117:258–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guido R. Human papillomavirus and cervical disease in adolescents. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;51(2):290–305. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318172d0dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maissi E, Marteau TM, Hankins M, Moss S, Legood R, Gray A. The psychological impact of human papillomavirus testing n women with borderline or mildly dyskaryotic cervical smear test results: 6-month follow-up. British Journal of Cancer. 2005;92:990–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCaffery KJ, Irwig L, Turner R, et al. Psychosocial outcomes of three triage methods for the management of borderline abnormal cervical smears: an open randomised trial. BMJ. 2010;340:b4491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCaffery K, Waller J, Forrest S, Cadman L, Szarewski A, Wardle J. Testing positive for human papillomavirus in routine cervical screening: examination of psychosocial impact. BJOG. 2004;111:1437–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massad LS. Assessing new technologies for cervical cancer screening: beyond sensitivity. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2008;12 (4):211–315. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31817d750c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Cervical cancer in adolescents: screening, evaluation, and management. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116:469–472. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb30f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albright D. Clinformatics DataMart training conducted at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Aug 21, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JW-Y, Berkowitz Z, Saraiya M. Low-risk human papillomavirus testing and other nonrecommended human papillomavirus testing practices among US health care providers. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;118(1):4–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182210034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright JD, Davila RM, Pinto KR, et al. Cervical dysplasia in adolescents. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(1):115–120. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000165822.29451.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moscicki A-B, Ma Y, Wibbelsman C, et al. Risks for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-3 among adolescent and young women with abnormal cytology. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112(6):1335–1342. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818c9222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113(suppl):2855–2864. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed August 22, 2012];SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2009. 2011 Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/results_merged/sect_05_cervix_uteri.pdf.

- 24.Schwaiger C, Aruda M, LaCoursiere S, Rubin R. Current guidelines for cervical cancer screening. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2012;24:417–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]