Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether sexual orientation is associated with disparities in teen pregnancy and hormonal contraception use among adolescent females in two intergenerational cohorts.

Study Design

Data were collected from 91,003 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII),born between 1947–1964, and 6,463 of their children, born between 1982–1987, enrolled in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS). Log-binomial models were used to estimate risk ratios (RR) for teen pregnancy and hormonal contraception use in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals and meta-analysis techniques were used to compare the two cohorts.

Results

Overall, teen hormonal contraception use was lower and teen pregnancy was higher in NHSII than GUTS. In both cohorts, lesbians were less likely, whereas the other sexual minorities were more likely, to use hormonal contraception as teenagers compared to their heterosexual peers. All sexual minority groups in both cohorts, except NHSII lesbians, were at significantly increased risk for teen pregnancy, with RRs ranging from 1.61 (95%CI 0.40, 6.55) to 5.82 (95%CI 2.89, 11.73). Having a NHSII mother who was pregnant as a teen was not associated with teen pregnancy in GUTS participants. Finally, significant heterogeneity was found between the two cohorts.

Conclusions

Adolescent sexual minorities have been, and continue to be, at increased risk for pregnancy. Public health and clinical efforts are needed to address teen pregnancy in this population.

Keywords: Bisexuality, Contraceptive Agents, Healthcare Disparities, Homosexuality, Sexual Behavior, Pregnancy in Adolescence

Background

Regardless of intention, teen pregnancy is associated with numerous adverse health and social outcomes. Compared to women who give birth in their 20s, teens are more likely to experience a quicker repeat pregnancy, more unemployment, poverty, and welfare reliance, and single parenthood. Infants of teen mothers are more likely to be premature and die before the age of one year. Compared to children of older mothers, these children also do more poorly on indicators of health and social wellbeing.(2, 3)

Although research examining pregnancy rates by sexual orientation is sparse, prior studies suggest that sexual minority females (e.g., bisexuals, lesbians, etc) may be at heightened risk compared to heterosexual peers.(4–6) Risk factors for teen pregnancy, such as earlier sexual initiation and more sexual partners(7), are more common in female sexual minorities who report a high proportion of male sexual contacts, a younger age of sexual initiation, and more partners (male or female) compared to heterosexuals.(4, 8, 9) Sexual minority females at risk for unintended pregnancy may also be less likely than heterosexual females to use contraceptives, and, in particular, highly effective hormonal contraceptives. One study found that this group underutilizes regular reproductive health screenings such as Pap smears and sexually transmitted infection (STI) tests, in which contraceptive counseling is offered.(9) In addition, sexual minority adolescent females may have additional risk factors such as engaging in risky sexual behavior with men, in order to hide their sexual orientation.(10)

Sex education,(11) contraceptive technology,(12) and attitudes about sexual orientation have changed over time and have affected historical trends in teen pregnancy and contraceptive use.(13) For example, comprehensive sex education has been shown to reduce teen pregnancy compared to no education or abstinence-only education.(14) Additionally, an estimated 60% of sexually active teens report using a highly effective form of contraception (e.g., intrauterine devices and hormonal methods) in 2010, which is an increase from 47% in 1995.(15) Contraception is less stigmatized than it was even one generation ago and physicians are more likely to raise the issue with patients.(16) Although initial research has been conducted on teen pregnancy among sexual minorities, these studies were of limited power, combined sexual minority groups, and were restricted to a single generation.

Using data from two intergenerational longitudinal cohort studies in which participants were teenagers during different periods (NHSII 1969–1983 and GUTS 1995–2006), we examined sexual orientation group disparities in teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy. We explored three aims: 1) sexual minority disparities; 2) intergenerational effects; and 3) historical cohort differences. First, we examined whether there were sexual orientation disparities in teen hormonal contraception and pregnancy. Next, we focused on the effect of having a mother with a teen pregnancy on her daughter’s risk of teen pregnancy. Thirdly, we formally tested for differences between the two generations. For aim 1, we hypothesized that compared to completely heterosexual females, that sexual minorities would be less likely to use hormonal contraception as teens in both cohorts. We also hypothesized sexual minority teenagers would have higher risks of becoming pregnant before age 20 in both NHSII and GUTS cohorts. For aim 2, we expected having a mother with a teen pregnancy would be associated with her daughter’s teen pregnancy risk. Finally for aim 3, we hypothesized that all of the disparities would vary historically and be more pronounced among the NHS cohort compared to the GUTS cohort.

Methods

Study Sample

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) is a longitudinal cohort that began in 1989, enrolling 116,678 female nurses from 14 U.S. states. Participants were between 25 and 42 years of age at baseline and born between 1947 and 1964. This cohort has been, and continues to be, followed with the use of biennial mailed questionnaires to update information on health-related behavior and to determine incident disease outcomes. In 1996, the NHSII women provided consent and contact information for their children between the ages of 9 and 14 years, born between 1982 and 1987, thereby creating another longitudinal cohort known as the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS). Questionnaires were mailed to more than 25,000 of these children; 9,039 girls (68%) and 7,843 (58%) boys returned completed questionnaires, indicating their consent. When NHSII or GUTS participants failed to respond to the first few mailings, extensive follow-up procedures were implemented to ensure a high response rate. More detailed information on recruitment and study protocols are available elsewhere.(17, 18) We limited the current analysis to female NHSII and GUTS participants who reported their sexual orientation, age, race, and geographic region (N=88,398). This study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital institutional review board.

Measures

Sexual orientation

In 1995, the following question was added to the long form of the NHSII questionnaire, after being pilot tested (19): “Whether or not you are currently sexually active, what is your sexual orientation or identity? (Please choose one answer). (1) Heterosexual, (2) Lesbian, gay, or homosexual, (3) Bisexual, (4) None of these, (5) Prefer not to answer.” For ease of interpretation, analyses did not include participants who responded with “None of these” or “Prefer not to answer” (1%, N=616).

Sexual orientation is measured in GUTS with a question adapted from the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey(20) asking about identity and feelings of attraction: “Which of the following best describes your feelings? (1) Completely heterosexual (attracted to persons of the opposite sex), (2) Mostly heterosexual, (3) Bisexual (equally attracted to men and women), (4) Mostly homosexual, (5) Completely homosexual (gay/lesbian, attracted to persons of the same sex), (6) Not sure.” We collapsed the “mostly heterosexual” and “bisexual” groups to form one category, because preliminary analyses showed that associations with predictors and outcomes were similar in the two groups and combining them increased statistical power. Similarly, the “mostly homosexual” and “completely homosexual” responses were combined to form a lesbian category. Again, analyses did not include participants who were unsure (N=6) or missing (N=14) the orientation item response. Additionally, the sex of participants’ sexual contacts was measured with an item reading: “During your life, the person(s) with whom you have had sexual contact is (are)…” Responses included “I have not had sexual contact with anyone,” “Females,” “Males,” or “Female(s) and Male(s).” An indicator variable was used for missing data on the sex of sexual contacts (N=33). An individual could therefore endorse being a sexual minority through their identity/attractions in the first question above and/or through their behavior in the next question.

This analysis used the most recently available data in NHSII from 1995 to categorize the following sexual orientation groups for that cohort as: “heterosexual,” “bisexual,” or “lesbian, gay, or homosexual.” The most recently available GUTS data from 2007 were used to categorize that cohort into the following groups: “completely heterosexual” with no same-sex partners, “completely heterosexual” with same-sex partners, “mostly heterosexual/bisexual,” or “mostly homosexual/completely homosexual.”

Teen hormonal contraceptive use

NHSII participants reported their history of using oral contraceptives on the 1989 baseline questionnaire. Beginning in 1999, each GUTS questionnaire has included various questions about oral contraceptives as well as more newly available hormonal contraceptives (see appendix). We categorized participants as a teen hormonal contraception user if they reported any such use before age 20.

Teen pregnancy

Similarly, NHSII participants reported their pregnancy histories on the 1989 baseline questionnaire. Beginning in 1999, each GUTS questionnaire included questions about pregnancy (see appendix). We defined teen pregnancy as occurring before the age of 20. Using this definition enabled comparisons between our findings and the previous literature on teen pregnancy, including among sexual minorities.

Covariates

Additional covariates included age, race, and geographic region based on a priori knowledge and available data in both cohorts. Age and racial information were collected on both baseline cohort questionnaires in 1989 for NHSII and 1996 for GUTS. Geographic region was accessed in NHSII from an item on the 1993 questionnaire that read: “In which state did you live at age 15?” GUTS geographic region was collected on each questionnaire, so we assigned the region at which each participant indicated they lived at age 15. Analyses did not include participants who did not report their race [N=1,798 (1.5%) in NHSII and N=26 (.4%) in GUTS] or geographic region [N=2,007 (2.1%) in NHSII]. GUTS participants who reported living outside of the United States at age 15 were also excluded due to small sample size (N=11).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and multivariable regression analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software 9.2.(22) All analyses were cross-sectional with heterosexual females in NHSII and completely heterosexual females with no same-sex partners in GUTS as the reference groups. Log-binomial models were used to estimate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the outcomes of teen hormonal contraceptive use and pregnancy.(23, 24) When the models did not converge, log-Poisson models were used, which provide consistent but not fully efficient estimates of the RR and its 95% CI.(25) Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to account for sibling clusters in GUTS.

Additional analyses were conducted to examine the effect of having a NHSII mother who was pregnant as a teen on the risk of having a pregnancy before age 20 years among GUTS participants. Finally, the two cohorts were compared on both outcomes using meta-analysis techniques to examine heterogeneity.(26, 27) Statistical tests for between-study heterogeneity were the chi-squared test for heterogenity (Cochran Q-statistic) and the I2 statistic, which estimates the proportion of total variance due to between-study variability.

Results

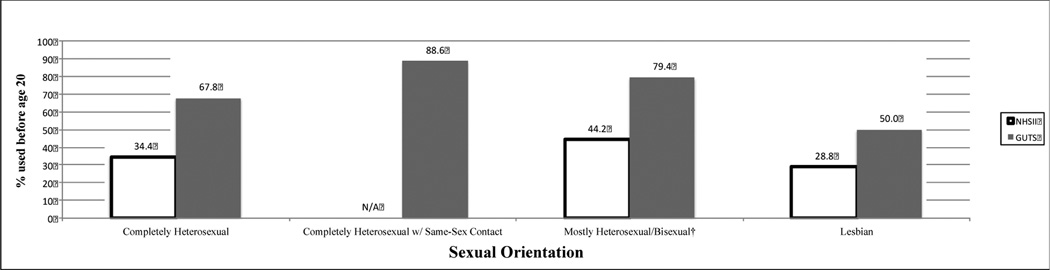

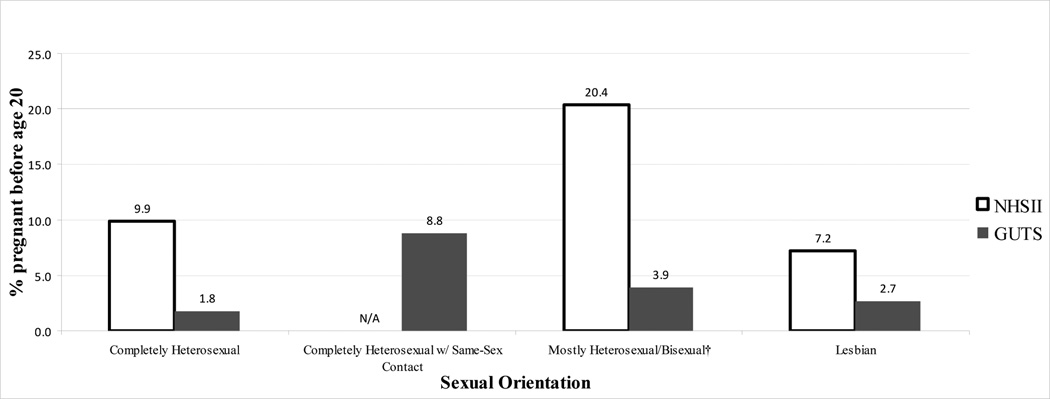

Among the 81,974 NHSII participants included in the analyses, 99% described themselves as heterosexual, <1% as bisexual, and 1% as lesbian. Among the 6,424 GUTS female participants included in the analyses, 84% described themselves as completely heterosexual, 1% as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners, 14% as mostly heterosexual/bisexual, and 1% as lesbian. Table 1 displays further characteristics of the two cohorts by sexual orientation. Teen hormonal contraception use was reported by 34% of NHSII women and 69% of GUTS participants, while 10% of NHSII women (mean age=18.0 years) and 2% of GUTS participants (mean age=17.9 years) reported a teen pregnancy.

Table 1.

Demographics and teen pregnancy and hormonal contraceptive use by sexual orientation in two intergenerational cohorts* of U.S. females (N=88,398).

| NHSII (N=81,974) | Heterosexual (N=81,053) |

Bisexual (N=283) |

p-value‡ | Lesbian (N=638) |

p-value‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean baseline age, years (SD) | 34.5 (4.7) | 35.2 (4.4) | .01 | 35.3 (4.6) | <.0001 | ||

| (Range: 24–44 years) | |||||||

| White race, % (N) ‡ | 94.2 (76,372) | 94.4 (267) | .93 | 96.9 (618) | .003 | ||

| Geographic region at age 15, % (N)‡ | |||||||

| Midwest | 36.5 (29,547) | 26.5 (75) | 27.6 (176) | ||||

| West | 10.8 (8,769) | 12.7 (36) | 15.7 (100) | ||||

| South | 13.4 (10,887) | 13.4 (38) | 15.7 (100) | ||||

| Northeast | 37.3 (30,253) | 44.5 (126) | 38.2 (244) | ||||

| International | 2.0 (1,597) | 2.8 (8) | <.0001 | 2.8 (18) | .001 | ||

| Hormonal contraceptive use <20 years old, % (n) | 34.4 (27,870) | 44.2 (125) | <.0001 | 28.8 (184) | .003 | ||

| Pregnancy <20 years old, % (n) | 9.9 (7,882) | 20.4 (56) | <.0001 | 7.2 (44) | .02 | ||

| Completely Heterosexual |

Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners |

Mostly Heterosexual/ Bisexual |

|||||

| GUTS (N=6,424) | (N=5,368) | (N=91) | p-value*† | (N=891) | p-value†‡ | Lesbian (N=74) |

p-value†‡ |

| Mean baseline age, years (SD) | 11.5 (1.6) | 12.2 (1.5) | <.0001 | 11.7 (1.6) | .0006 | 12.0 (1.6) | .004 |

| (Range: 9–15) | |||||||

| White race, % (N) | 94.1 (5,052) | 96.7 (88) | .20 | 90.0 (802) | <.0001 | 91.9 (68) | .70 |

| Geographic region at age 15, % (N) | |||||||

| Midwest | 36.6 (1,967) | 35.2 (32) | 30.4 (271) | 23.0 (17) | |||

| West | 13.7 (734) | 13.2 (12) | 19.6 (175) | 10.8 (8) | |||

| South | 14.8 (792) | 16.5 (15) | 11.5 (102) | 21.6 (16) | |||

| Northeast | 34.9 (1,875) | 35.2 (32) | .39 | 38.5 (343) | .37 | 44.6 (33) | .62 |

| Hormonal contraceptive use <20 years old, % (n) | 67.8 (3,535) | 88.6 (78) | <.0001 | 79.4 (681) | <.0001 | 50.0 (34) | .004 |

| Pregnancy <20 years old, % (n) | 1.8 (95) | 8.8 (8) | .02 | 3.9 (35) | .001 | 2.7 (2) | .64 |

| NHSII mother had teen pregnancy, % (n) | 7.1 (356) | 12.6 (11) | .04 | 9.0 (76) | .06 | 5.9 (4) | .68 |

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) participants were born between 1947–1964 and their children, born between 1982–1987, were enrolled in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

P values estimated by generalized estimating equation regression

Completely heterosexual is referent group.

The multivariable RRs for teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy are displayed in Table 2 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region. In both cohorts, lesbians were less likely, whereas the other sexual minorities (NHSII: bisexuals, GUTS: completely heterosexuals with same-sex partners and mostly heterosexual/bisexuals) were more likely, to use hormonal contraception as teenagers compared to their heterosexual peers. All sexual minority groups, except NHSII lesbians, were at increased risk for teen pregnancy, with RRs as high as 5.82 (95% CI 2.89, 11.73) among GUTS participants who identified as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners (pregnancy N=8). Having a NHSII mother who was pregnant as a teen was not associated with teen pregnancy in GUTS participants on a univariate level nor did it have any effect in further adjusting the multivariable sexual orientation model. Finally, significant heterogeneity was found between the two cohorts for teen hormonal contraceptive use and pregnancy, with the I2 value estimating 92% (p=0.01) and 95% (p=0.003), respectively, of the total variance being due to between-study variability.

Table 2.

Multivariable risk ratios (RR)* for teen hormonal contraceptive use and pregnancy in two intergenerational cohorts† of U.S. females (N=88,398)

| Teen hormonal contraceptive use |

Teen Pregnancy |

|

|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| NHSII (N=81,974) | ||

| Heterosexual (N=81,053) | ref | ref |

| Bisexual (N=283) | 1.26 (1.12, 1.43) | 2.08 (1.64, 2.62) |

| Lesbian (N=638) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.95) | 0.72 (0.54, 0.96) |

| GUTS (N=6,424) | ||

| Completely Heterosexual (N=5,368) | ref | ref |

| Completely Heterosexual with Same-Sex Partners (N=91) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) | 5.82 (2.89, 11.73) |

| Mostly Heterosexual/Bisexual (N=891) | 1.11 (1.07, 1.15) | 2.28 (1.53, 3.39) |

| Lesbian (N=74) | 0.72 (0.57, 0.90) | 1.61 (0.40, 6.55) |

All models adjusted for age, race (white/nonwhite), and region [Northeast (ref), Midwest, West, South, and International].

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) participants were born between 1947–1964 and their children, born between 1982–1987, were enrolled in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

Discussion

Although teen pregnancy rates were dramatically reduced in a single generation, our study showed that there were sexual orientation disparities in teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy that have persisted across two generations. The general trends are consistent with findings from other national data sources, which report steadily rising teen pregnancy rates while NHSII participants were teens (1969–1983).(1) By the time GUTS participants were teens, the teen pregnancy rate decreased 41%.(28) A decrease in both birth and abortion rates demonstrates that intended and unintended pregnancy rates declined.(1) This decline was attributable to reduced sexual activity and increased contraceptive use.(29)

All sexual minority groups in both cohorts were at increased risk for teen pregnancy, except NHSII lesbians, with relative risks as high as five-fold. While few studies have examined this issue, our findings are supported by the literature.(6, 8, 34), but these studies were limited in power and combined sexual minorities into a single category. Saewyc et al. reported that from a sample of 3,816 adolescents in Minnesota, 12.3% of bisexuals/lesbians (combined) experienced a teen pregnancy compared to 5.3% of heterosexual adolescents. Another study explored teen pregnancy rates by sex and sexual orientation in six school-based cohorts from various regions around the U.S. Again, bisexual and lesbian teens were more likely in each region to report pregnancy histories than heterosexual peers.(34)

The origins of these disparities are complex. First, factors associated with teen pregnancy in the general population(7) such as earlier sexual initiation(9, 38–40), more sexual partners(4, 9), and ineffective contraception(8, 38, 39) are more common in sexual minorities. Adolescents who have been sexually abused are more likely to report these risks(35) as are homeless youth.(36, 37) Sexual minority youth are more likely to report being sexually abused(8, 39) and make up a disproportionately large portion of homeless youth.(41) Heterosexual women with same-sex partners might be at especially high risk for teen pregnancy due to particular risk factors. For example, having same-sex partners while identifying as a heterosexual could be a marker for risky behavior. Previous studies in this cohort also indicate that these women have more than twice as much sexual abuse history compared to their heterosexual peers.(42)

There may also be risk factors that are specific to sexual minority adolescents. For example, they may engage in strategies to avoid or cope with stigma about their sexual orientation(10, 43) including sexual intercourse with the opposite sex and subsequent pregnancy involvement. Increased substance abuse among sexual minorities may be another coping strategy(44, 45) that can lead to unintended and unprotected sexual intercourse. Finally, sexual minority health is often overlooked in sex education so these youth may not receive appropriate education and counseling about contraception and other healthy decisions.(10)

When examining intergenerational affects, having a NHSII mother who was pregnant as a teen was not associated with increased risk for a teen pregnancy among the GUTS children nor did it have any affect in further adjusting the multivariable sexual orientation model. Teenage pregnancy is a complex phenomenon and involves numerous risk factors as well as protective mechanisms. Matrices and causal models have been published that include hundreds of variables,(47) such as poverty, growing up in a single-family household, and, most importantly, unprotected sexual intercourse. Some studies have found that being the child of teenage parents was a risk factor for a having a teen pregnancy (3, 48) but our results did not support this.

The significant cohort differences likely exist for many reasons. NHSII women may have been less likely to use hormonal contraceptives than GUTS participants since these were not as readily available during earlier generations. The FDA approved oral contraceptives for birth control use in 1960 when all of the NHSII participants were <13 years old, though some states prohibited their use in unmarried women. This statute was overturned in 1972, when NHSII women were aged 8–25 years, with Eisenstadt v. Baird.(21) The average age of marriage was also lower when NHSII participants were teenagers compared to their daughters(46) so more of the teen pregnancies among NHSII women may have been planned. However, because collecting accurate information about pregnancy intention is difficult, we cannot examine this dimension.(1) Nonetheless, even if a teen pregnancy is planned and wanted, the outcomes are still worse overall for the mother and her child compared to having a child later in adulthood.

Some limitations should be mentioned. All of the NHSII women are nurses and the GUTS participants are the children of nurses. Therefore, neither group is a nationally representative sample, which could limit generalizability. Sexual orientation effects would need to differ by socioeconomic status or race in order to limit generalizability so this should also be further explored in future analyses. Daughters of nurses may have more healthcare access than the general population, which could lead to an overestimation of hormonal contraceptive use.

Because our study population included professional women along with their children, the majority of whom were white, the absolute risk of teen pregnancy in this population is lower than the national average and therefore does not capture the full extent of this public health problem. Sexual orientation was measured slightly differently in the two cohorts, but this is a complex measurement and methods are progressing. Sexual identity and behavior are fluid so we also cannot know the circumstances of each teen pregnancy nor how the participants identified in regards to the sexual orientation at the time of the pregnancy. Using a single measure of sexual orientation may also have led to some misclassification. Measurement of other types of contraceptives was limited so we could not explore this. We were also able to study only female adolescents, though there is evidence to believe that teen male sexual minorities are at increased risk for having a pregnancy involvement.(8, 49)

Nonetheless, our analysis contributed in new ways and had a number of strengths such as the large sample not recruited on the basis of sexual orientation. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine teen contraceptive use and pregnancy among various sexual orientation subgroups and across generations, allowing us to examine historical trends as well as the intergenerational effects of a teen pregnancy. We were able to more precisely observe different sexual orientation identity groups, highlighting the differences not only between heterosexuals and sexual minorities but also across sexual minority subgroups.

Although teen pregnancy rates have declined over the last few decades in part due to increased use of effective contraception, there are still disparities by sexual orientation. Clinical and public health practitioners need to be aware of such disparities and develop innovative ways to help these women avoid pregnancy during adolescence and subsequent adverse outcomes for the parents and children.

Background and Objective

Although research examining teen pregnancy rates by sexual orientation is sparse, prior studies suggest that sexual minority females (eg, bisexuals, lesbians) may be at heightened risk compared to heterosexual peers. Risk factors for teen pregnancy, such as earlier sexual initiation and more sexual partners, are more common in female sexual minorities who report a high proportion of male sexual contacts, a younger age of sexual initiation, and more partners (male or female) compared to heterosexuals. Sexual minority females at risk for unintended pregnancy may also be less likely than heterosexual females to use contraceptives and, in particular, highly effective hormonal contraceptives. Sexual minority adolescent females may have additional risk factors, such as engaging in risky sexual behavior with men, to hide their sexual orientation.

Using data from 2 intergenerational longitudinal cohort studies in which participants were teenagers during different periods (NHSII 1969–1983 and GUTS 1995–2006), we examined sexual orientation group disparities in teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy. We explored 3 aims: 1) sexual minority disparities; 2) intergenerational effects; and 3) historical cohort differences.

Materials and Methods

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) began in 1989, enrolling 116,678 female nurses from 14 US states. Participants were 25–42 years of age at baseline and born in 1947–1964. This cohort has been, and continues to be, followed with the use of biennial mailed questionnaires to update information on health-related behavior and to determine incident disease outcomes.

In 1996, the NHSII women provided consent and contact information for their children from ages 9 through 14 years, born in 1982–1987, thereby creating another longitudinal cohort known as the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS). Questionnaires were mailed to more than 25,000 of these children; 9039 girls (68%) and 7843 (58%) boys returned completed questionnaires, indicating their consent.

Our analysis of the sexual orientation part of the NHSII questionnaire used the most recently available data in NHSII from 1995 to categorize the following sexual orientation groups for that cohort as “heterosexual,” “bisexual,” or “lesbian, gay, or homosexual.” The most recently available GUTS data from 2007 were used to categorize that cohort into the following groups: “completely heterosexual” with no same-sex partners, “completely heterosexual” with same-sex partners, “mostly heterosexual/bisexual,” or “mostly homosexual/completely homosexual.”

NHSII participants reported their history of using oral contraceptives and pregnancy on the 1989 baseline questionnaire. Beginning in 1999, each GUTS questionnaire has included various questions about oral contraceptives as well as more newly available hormonal contraceptives and pregnancy. We defined teen pregnancy or hormonal contraceptive use as occurring before age 20.

Results

Teen hormonal contraception use was reported by 34% of NHSII women and 69% of GUTS participants. Teen pregnancy was reported by 10% of NHSII women (mean age, 18.0 years) and 2% of GUTS participants (mean age, 17.9 years).

Multivariable RRs were determined for teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy after adjustment for age, race, and geographic region (Table). In both cohorts, lesbians were less likely, whereas the other sexual minorities (NHSII: bisexuals, GUTS: completely heterosexuals with same-sex partners and mostly heterosexual/bisexuals) were more likely, to use hormonal contraception as teenagers compared to their heterosexual peers. All sexual minority groups except NHSII lesbians were at increased risk for teen pregnancy, with RRs as high as 5.82 (95% CI, 2.89–11.73) among GUTS participants who identified themselves as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners (pregnancy n=8).

Having an NHSII mother who was pregnant as a teen was not associated with teen pregnancy in GUTS participants on a univariate level, nor did it have any effect in further adjustment of the multivariable sexual orientation model. Significant heterogeneity was found between the 2 cohorts for teen hormonal contraceptive use and pregnancy, with the I2 value estimating 92% (P=.01) and 95% (P=.003), respectively, of the total variance due to between-study variability.

Comment

Although teen pregnancy rates were dramatically reduced in a single generation, our study identified sexual orientation disparities in teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy that have persisted across 2 generations. The origins of these disparities are complex. Factors associated with teen pregnancy in the general population, such as earlier sexual initiation, more sexual partners, and ineffective contraception, are more common in sexual minorities. There may also be risk factors specific to sexual minority adolescents. For example, they may engage in strategies to avoid or cope with stigma about their sexual orientation, including sexual intercourse with the opposite sex and subsequent pregnancy involvement. Increased substance abuse among sexual minorities may be another coping strategy that can lead to unintended and unprotected sexual intercourse. Because sexual minority health is often overlooked in sex education, these youth may not receive appropriate education and counseling about contraception and other healthy decisions.

Some limitations should be mentioned. All NHSII women are nurses and the GUTS participants are the children of nurses. Therefore, neither group is a nationally representative sample, which could limit generalizability.

Nonetheless, our analysis contributed in new ways and had a number of strengths, such as the large sample not recruited on the basis of sexual orientation. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine teen contraceptive use and pregnancy among various sexual orientation subgroups and across generations, allowing us to examine historical trends as well as the intergenerational effects of a teen pregnancy. We were able to more precisely observe different sexual orientation identity groups, highlighting the differences not only between heterosexuals and sexual minorities but also across sexual minority subgroups.

Although teen pregnancy rates have declined over the last few decades in part due to increased use of effective contraception, there are still disparities by sexual orientation. Clinical and public health practitioners need to be aware of such disparities and develop innovative ways to help these women avoid pregnancy during adolescence and subsequent adverse outcomes for the parents and children.

Figure 1.

Teen Hormonal Contraceptive Use in Two Intergenerational Cohorts* of U.S. Females

*The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) participants were born between 1947–1964 and their children, born between 1982–1987, were enrolled in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

†Includes NHSII bisexuals and GUTS mostly heterosexuals/bisexuals.

Figure 2.

Teen Pregnancy in Two Intergenerational Cohorts* of U.S. Females

*The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) participants were born between 1947–1964 and their children, born between 1982–1987, were enrolled in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

†Includes NHSII bisexuals and GUTS mostly heterosexuals/bisexuals.

Appendix.

Questionnaire information by cohort.

| Question | Year |

|---|---|

| NHSII | |

| “Mark each age of oral contraceptive (OC) use for…2 months or more” and “…a full year (10+ months).” | 1989 |

| “Mark each age you…completed a pregnancy lasting 6 months or more” and “…completed a pregnancy | 1989 |

| lasting less than 6 months.” | |

| GUTS | |

| “The last time you had sexual intercourse, what method(s) did you or your partner use to prevent pregnancy?” including a “birth control pill” response. |

1999 |

| “Have you ever used birth control pills or injectable estrogen (Lunelle) for any reason?” | 2001 |

| “Have you ever used birth control pills, patch (Ortho-Evra), ring (Nuvaring), Depo Provera, or injectable estrogen (Lunelle) for any reason?” |

2003+ |

| “How many times have you been pregnant?” | 1999 |

| “Have you been pregnant or are currently pregnant?” | 2001 |

| “Have you been pregnant or breast feeding in the past year?” | 2003+ |

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS.

There are documented disparities in teen hormonal contraception use and pregnancy by sexual orientation.

Although teen pregnancy rates have declined over the last few decades, these disparities have persisted across 2 generations.

Clinical and public health practitioners need to be aware of such disparities and develop innovative preventive approaches.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant R01HD057368 from the National Institutes of Health. HL Corliss and SB Austin are supported by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Project grant T71 MC 00009 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. HL Corliss is also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant K01 DA023610. BM Charlton is supported by the Training Program in Cancer Epidemiology grant T32 CA 09001–36. BM Charlton had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

This paper was highlighted as an oral presentation at the Annual American Public Health Association Conference held October 27–31, 2012 in San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Kost K, Henshaw S. U.S. teenage pregnancies, births and abortions, 2008: national trends by age, race, and ethnicity. New York: Guttmacher Institute.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sex and America’s teenagers. New York: Guttmacher Institute.; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman S. By the numbers: the public costs of teen childbearing. Washington, DC National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE. Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. Am J Public Health. 2008 Jun;98(6):1015–20. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004 Nov;13(9):1033–47. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saewyc EM, Bearinger LH, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Sexual intercourse, abuse and pregnancy among adolescent women: does sexual orientation make a difference? Fam Plann Perspect. 1999 May-Jun;31(3):127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein JD. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005 Jul;116(1):281–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Hack T. Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: the benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jun;91(6):940–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, et al. Reproductive health screening disparities and sexual orientation in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent and young adult females. J Adolesc Health. 2011 Nov;49(5):505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saewyc EM, Poon CS, Homma Y, Skay CL. Stigma management? The links between enacted stigma and teen pregnancy trends among gay, lesbian, and bisexual students in British Columbia. Can J Hum Sex. 2008;;17(3):123–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran JP. Teaching sex: the shaping of adolescence in the 20th century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tone A. Devices and desires. a history of contraceptives in America. 1st. New York: Hill and Wang; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inside out: a report on the experiences of lesbians, gays and bisexuals in America and the public’s views on issues and policies related to sexual orientation. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler PK, Manhart LE, Lafferty WE. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2008 Apr;42(4):344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Sexual experience and contraceptive use among female teens — United States, 1995, 2002, and 2006–2010. MMWR. 2012;;61(17):297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralph LJ, Brindis CD. Access to reproductive healthcare for adolescents: establishing healthy behaviors at a critical juncture in the lifecourse. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2010 Oct;22(5):369–74. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32833d9661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurses’ Health Study. Brighman and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School. [cited 2010 August 3]; Available from: http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/

- 18.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, et al. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Jun;38(6):754–60. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Disclosure of sexual orientation and behavior in the Nurses’ Health Study II: results from a pilot study. J Homosex. 2006;51(1):13–31. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992 Apr;89(4 Pt 2):714–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junod SW, Marks L. Women’s trials: the approval of the first oral contraceptive pill in the United States and Great Britain. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2002 Apr;57(2):117–60. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/57.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAS Statistical Software, Release 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institue Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner S, Li R, Hertmark E, Spiegelman D. The SAS RELRISK9 Macro. 2011 [cited 2011 December 22]; Available from: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/faculty/donna-spiegelman/files/relrisk9.pdf.

- 24.Wacholder S. Binomial regression in GLIM: estimating risk ratios and risk differences. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Jan;123(1):174–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986 Sep;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hertmark E, Spiegelman D. The SAS METAANAL Macro. 2010 [cited 2011 December 22]; Available from: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/faculty/donna-spiegelman/files/metaanal.pdf.

- 28.Teen pregnancy in the United States. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Washington: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB, Singh S. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):150–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones R. Beyond birth control: the overlooked benefits of oral contraceptive pills. New York: Guttmacher Institute.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersch B, Milsom I. An epidemiologic study of young women with dysmenorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Nov 15;144(6):655–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillen TI, Grbavac SL, Johnston PJ, Straton JA, Keogh JM. Primary dysmenorrhea in young Western Australian women: prevalence, impact, and knowledge of treatment. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Jul;25(1):40–5. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG. 2010 Jan;117(2):185–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saewyc E, Pettingell S, Skay C. Teen pregnancy among sexual minority youth in populationbased surveys of the 1990s: Countertrends in a population at risk [Abstract] Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34:125–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell SE. Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004 May-Jun;36(3):98–105. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.98.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrow JA, Deisher RW, Brown R, Kulig JW, Kipke MD. Health and health needs of homeless and runaway youth A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1992 Dec;13(8):717–26. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90070-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thrane LE, Chen X. Impact of running away on girls’ sexual onset. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Jan;46(1):32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of vermont and massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002 Apr;156(4):349–55. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saewyc E, Skay C, Richens K, Reis E, Poon C, Murphy A. Sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2006 Jun;96(6):1104–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Pettingell SL, et al. Hazards of stigma: the sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare. 2006 Mar-Apr;85(2):195–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corliss HL, Goodenow CS, Nichols L, Austin SB. High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative Massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health. 2011 Sep;101(9):1683–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Elevated Risk of Posttraumatic Stress in Sexual Minority Youths: Mediation by Childhood Abuse and Gender Nonconformity. Am J Public Health. 2012 Aug;102(8):1587–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubington E, Weinberg MS. Deviance, the interactionist perspective; text and readings in the sociology of deviance. New York: Macmillan; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Wylie SA, Frazier AL, Austin SB. Sexual orientation drug use in a longitudinal cohort study of U.S adolescents. Addict Behav. 2010 May;35(5):517–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008 Apr;103(4):546–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreider R, Ellis R. Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009. U.S. Census Bureau.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirby D, Lapore G. A matrix of risk and protective factors affecting teen sexual behavior, pregnancy, childbearing, and sexually transmitted disease. Washington: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seamark CJ, Pereira Gray DJ. Like mother, like daughter: a general practice study of maternal influences on teenage pregnancy. Br J Gen Pract. 1997 Mar;47(416):175–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodenow C, Netherland J, Szalacha L. AIDS-related risk among adolescent males who have sex with males, females, or both: evidence from a statewide survey. Am J Public Health. 2002 Feb;92(2):203–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]